Raph Koster's Blog, page 12

December 3, 2014

Practicing the creativity habit

In the wake of posting up the video of my talk on “Practical Creativity,” I got this:

@raphkoster how do you usually practice the creativity habit?

— Karlos Zafra (@solkar) December 3, 2014

What a great question.

First, I have to admit I slack off a lot.  But, here are some ways in which I practice, or have practiced it. You might notice some commonalities across media.

But, here are some ways in which I practice, or have practiced it. You might notice some commonalities across media.

Hope you’ll bear with me, because I will get to games last.

Music

My current list of musical instruments within ten feet of me, clockwise order:

mountain dulcimer

cuatro

mandolin

baritone ukulele

piano

banjo

slide guitar

acoustic guitar

electric guitar

bass

MIDI guitar

tambourine

bongos

kalimba

charango

metal flute

maracas

bamboo flute

Oh, and there’s a saxophone in the closet. Now, a few of these aren’t mine (I can’t play the flute, or the sax!). The point being, just like I have game tools within close reach, I have music tools within close reach.

Oh, and there’s a saxophone in the closet. Now, a few of these aren’t mine (I can’t play the flute, or the sax!). The point being, just like I have game tools within close reach, I have music tools within close reach.

When I sit down to write a piece of music, I try to avoid linking together two chords that I have used in a progression before. That’s near impossible, if you stick to standard tuning and standard chords. But I don’t. I try to explore new tunings, new instruments, putting capos and partial capos on with abandon. It leads me to new places and new harmonies.

The other day I was fiddling around with this piece. It’s in DADGAD, which is itself an alternate tuning, but then I put a partial capo on just three of the strings, up at the fourth fret. Why? Mostly to force myself to use fingerings I don’t use. Pairings of notes that I wouldn’t play when I am trapped in the muscle memory of the standard chords.

[See post to listen to audio]

Similarly, I decided a week or so ago to learn jazz chords. Probably long overdue, since as soon as I started, I found that I had been using several of them in my standard chord vocabulary for a long time now. But there’s a new sonic palette there, and also now a new rhythmic palette, since it kind of begs for bossa nova rhythms or the like. (Now I want a nylon-string guitar, too).

In learning new compositional tools, doing covers is a fantastic approach. Or writing “in the style of” someone else. Taking their same chord progression, moving it to a new key, changing some of the chords just enough to land somewhere new.

Now, I am not a “sounds” person, just like I am not a visuals person. I have learned the absolute basics of audio engineering, and that’s it. I am much more interested in the writing of music — the notes, the melodies, the harmonies — than in the sounds of it, which puts me somewhat out of step with the way in which modern music works, to a large degree. For me, it’s about seeing the systems behind the surface of the production.

Writing

There was a period when I went absolutely everywhere with a notebook. (Today, it’s an iPad with a stylus). I would try to observe deeply, to look closely at whatever was around me and actually notice it. And I would try to put together a few words that went well together but were also an unusual pairing. I’d keep these piled up in my notebook, to pillage later. I no longer have the habit — being “a writer” is not how I define myself anymore, though it used to be. Perhaps one day it will be again.

I usually write best to deadline, actually. So participating regularly in a writer’s workshop was a great way to spur creativity for me. I had to come up with something, and it had to be something decent enough to be ripped apart by a pretty good crew of writers. (Back when I lived in Austin, my writer’s workshop was Turkey City; this meant some very good writers indeed).

I don’t have a writer’s workshop here in San Diego, so the lack of deadlines has been an issue in terms of practicing the habit. I self-imposed a Sunday Poem routine, which I unfortunately fell out of the habit of a while back. When writing poetry, especially back when I was in college, my greatest ally was Babette Deutsch’s Poetry Handbook: A Dictionary of Terms. I worked my way through that book trying to use every single technique in a poem. These things served as constraints, and as the gradual accumulation of tools for the workbench. I wrote concrete poetry too, where the typographical layout of the letters on the page matters. I even wrote a sonnet redoublé, and you know what, it wasn’t great but it functioned.

I don’t have a writer’s workshop here in San Diego, so the lack of deadlines has been an issue in terms of practicing the habit. I self-imposed a Sunday Poem routine, which I unfortunately fell out of the habit of a while back. When writing poetry, especially back when I was in college, my greatest ally was Babette Deutsch’s Poetry Handbook: A Dictionary of Terms. I worked my way through that book trying to use every single technique in a poem. These things served as constraints, and as the gradual accumulation of tools for the workbench. I wrote concrete poetry too, where the typographical layout of the letters on the page matters. I even wrote a sonnet redoublé, and you know what, it wasn’t great but it functioned.

Blogging itself has gotten more sporadic for me — in 2006 and 2007, I posted twice a day, just about! Twitter has had a huge impact on that (a very large amount of the posts on the blog used to be just “keeping up with the news” so to speak, with a dash of commentary). What would have been longer-form pieces instead have become shorter ones. So usually, to write I need a prompt that calls for a long-form answer, and the best prompt is a question. Like the one that prompted this post, actually.

On the other hand, speaking regularly has been a real prompt to create non-fictional material, even if not in the form of prose. My habit here is simple: No Repeats. I try to generate a new talk, with a new point to it, for every speaking invitation. (I get asked to repeat talks sometimes, though).

You cannot write if you do not read. As a teenager in Barbados, I kept a journal of everything I read. I stopped after a few months, because I had filled two notebooks. I read thousands of words a day. My book reading has diminished as the Internet has slaked my thirst for words and other hobbies have risen to the fore, but I still go through many books a month, many many dozens a year. Try to be indiscriminate and Catholic in your tastes; I fail at it, gravitating towards favorites, of course. But particularly with non-fiction, I find that there is something interesting in basically everything.

Art

I practice art far less than I do the other creative things I do. A long time ago I came to the conclusion that the artists around me saw the world in terms of visual art, and I didn’t. This meant that they effectively “practiced” all the time. I knew this meant I wasn’t a visual artist the same way they were; it wasn’t where my muse led me. So I practiced up to the level of competence, but not further, really.

I practice art far less than I do the other creative things I do. A long time ago I came to the conclusion that the artists around me saw the world in terms of visual art, and I didn’t. This meant that they effectively “practiced” all the time. I knew this meant I wasn’t a visual artist the same way they were; it wasn’t where my muse led me. So I practiced up to the level of competence, but not further, really.That said, some of the things I do on this front include an openness to new media and tools. For example, lately I have been downloading font creation software and trying it out. That’s basically a new discipline for me, but I am enjoying messing around with it. Long ago I used to hand-set type for letterpress printers, and this reminds me powerfully of that.

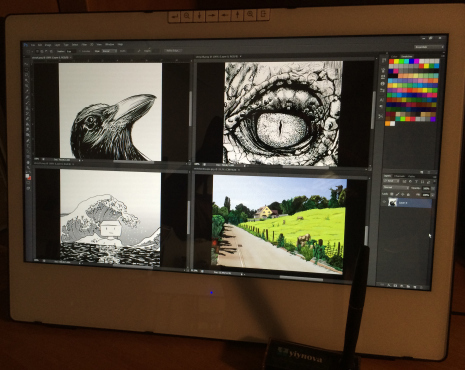

I also keep the tools around and at close hand. Within five feet of my chair I have pastels, oil paints, bristol paper, colored pencils, stumps, illustrator’s pens, drawing pencils from 7H to 7B, colored inks, and calligraphy and artist nibs for my collection of art pens. The fact that my drafting table is underused has much to do with the graphics tablet monitor I now use instead — once upon a time, I actually used to prefer to freehand draw tiling terrain tiles and scan them.

One place where I try to exercise my graphic design skills is when preparing PowerPoint slides. For me, a key part of the process is to use a new graphic design with every presentation. Sometimes they work really well. Other times they are real misses. I even give myself the constraint of not repeating fonts from the past.

Either way, I find it helpful to have my reference library. This is just a part of it, showing some of the art books towards the bottom. Even tracing stuff is a great way to get the shapes of things into your finger muscles. Copying a photo is a great way to learn to flatten space so you can draw it, because it pre-flattens it for you.

This is going to sound weird, but I have consistently found that part of the secret to being able to pull off something I have never done before is to just have the guts to go out there and persuade myself that I already know how. Studying books like this and then just doing it rather than over-thinking it or talking myself into the (utterly true) notion that I don’t have a clue.

Games

So, games.

Really, it’s all the things that I mentioned already in the talk, and that keep recurring in this post.

Really, it’s all the things that I mentioned already in the talk, and that keep recurring in this post.

Trace over what has ben done. Copy, clone, imitate, then twist it, to learn how it works.

Assemble a library of small parts you can go back to, that are tools on the workbench.

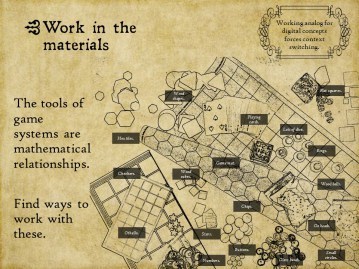

Work in the materials, not in the abstract.

Force yourself to the unfamiliar.

Be observant and diligent about gathering the observations.

Keep lots of notes.

For me, the inspirations for games often come from real-world systems. I have notes here on an aquarium simulation, for example. Most aquarium software is all about the pretty fishies swimming about. But as I tend my aquaria, or try to get fruit trees to grow, I am struck by the fact that they are rich and complicated systems with few exposed rules, massive tomes of cheat guides, and really bad feedback design. What about an aquarium game that actually went full sim? That had the stats for each fish’s generation of waste? That could model the rise of nitrates and nitrites? An advanced level could deal with each plant’s needs for phosphorous. There’s a game system there that just needs a good interface.

The same goes for code; I am often translating board games into code, or coded games into boards. It switches the context up. I got started as a game designer by doing ports of arcade games that I played in the States but that weren’t available in Peru. With scissors, paper, markers, and my collection of Video Games magazine, I made turn-based versions of Q*Bert and Pengo. It was an early lesson in rules deconstruction and analysis.

The reading portion, the studying need, is not only met by having a MAME cabinet and a dozen emulators and way way too many videogames and boardgames. It’s also met by bothering to investigate history, by maintaining documents like these. To be a serious creator in a craft is also to be a serious student of it.

I have loose materials everywhere! I’ve written before about my prototyping materials, which are basically a curated section of a craft store aisle. Colored cardstock paper, an assortment of different color Sharpies, wood bits in widely varied shapes, high-quality paper scissors, tons of dice, tokens and mats… I’ll often grab a random selection of these, and simply give myself the challenge to come up with something.

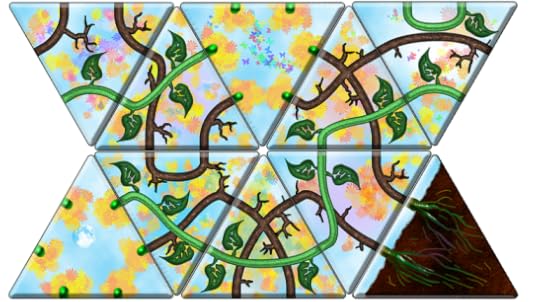

Right now, I am finishing up the graphic design on a trifle of a game I am calling Thicket, a little exercise in the classic tile-laying-path-connecting genre (like Entanglement, Tsuro , or Trax). It uses triangles. Why? Because The Game Crafter made triangle tiles available. That’s all. That plus exploring the Internet (this page especially) plus a lot of spreadsheeting to allow for multiple colors, and five days of mostly background cogitation, gave me a cross between standard pathing games and a territory battle.

, or Trax). It uses triangles. Why? Because The Game Crafter made triangle tiles available. That’s all. That plus exploring the Internet (this page especially) plus a lot of spreadsheeting to allow for multiple colors, and five days of mostly background cogitation, gave me a cross between standard pathing games and a territory battle.

Why territory battle? Well, I am cheerfully re-using a mechanic that worked out successfully in a hex-grid tile game I finished a couple of months ago. It’s a tool on the workbench, and it feels very different here, so why not? Remix away! I shouldn’t be ashamed of that any more than I should be of using Photoshop’s default butterflies and flower brushes.

Why territory battle? Well, I am cheerfully re-using a mechanic that worked out successfully in a hex-grid tile game I finished a couple of months ago. It’s a tool on the workbench, and it feels very different here, so why not? Remix away! I shouldn’t be ashamed of that any more than I should be of using Photoshop’s default butterflies and flower brushes.

Why this game? Because it is giving me a mental break from thinking about a different one, a small card game called Coalition that is about political networks. It has multiple unsettled rules still and doesn’t play as well as it should. These are the two games I designed this month, out of the dozen or so this year.

A few final thoughts

I think of my creative practice as a braid. It likely drives my family nuts, but I weave back and forth between music and art and writing and board games and code and other enthusiasms (fish, redoing a room, whatever!). Usually two or so are active “at a time.” As I lose energy on one, another surfaces, like monsters from the deep dark sea, like dolphins taking turns arcing over the subconscious.

I can’t imagine, personally, being stuck with just one medium or mode of expression, but that’s just me. It likely means that I’ll never get good enough at any given one of them, certainly not as good as a specialist.

But I like games because in games I can do all of them. I can observe systems, bring them into the unfamiliar, craft the visuals, write the music, develop the storyline, do some writing. So for me, games are where I can really use the braid.

It also means that sometimes an enthusiasm ends before a project does; I have a song cycle that sits at eight of ten, and has for six months now. There’s nothing to be done about it; I have to wait until the other songs show up. I have a game that stopped literally two pieces of artwork away from shipping (well, that and a control bug). Really should get that out the door. I always manage to find excuses.

One thing that I don’t have is a lot of patience for: the 90% of the work that is the polish. That’s what I really ought to have collaborators for: those people who do see the world in terms of visual arts, who think of the sonic experience as a whole, not just the song; those people who are the deep specialists who can do the things I can only fake my way through.

In the end, I touch one of the above creative endeavors, in some way, every single day. Usually, more than one, every single day. That means: I might play guitar for two hours. I might read for two hours. I might code for two hours. I might draw for two hours. I might work in a spreadsheet calculating odds. I might just rewrite the rules of a game from memory on separate pages in my iPad notebook, so that I can figure out what the parts that matter really are (it’ll be the parts that I always remember to include; the parts I forget are good candidates to cut). Even when I relax by watching some mindless TV, I’m liable to comment on where the story beats are falling and how a scene was directed.

A thought on privilege: you’re looking here at 30 years of accumulated tools, books, instruments, etc. But I didn’t start out with all these. My first guitar was a cheap Yamaha I basically stole from my brother. One of the boxes of colored pencils is a set of Caran D’Ache I think was given to me as a gift when I lived in South America. I’m a packrat and I still have my early writing fumblings from when I was ten, my drawings from when I was a teen — and the tools with which I made them.

Back when I was carrying that notebook with snatches of writing around, I was a grad student and my wife and I lived on $7000 a year. Don’t let the accumulation of stuff here fool you into thinking that you need everything I have gathered, and don’t let your lack of stuff fool you into thinking that you can therefore skip past the work of deconstructing, experimenting, paying dues, cloning, copying, tracing, reading endlessly.

The stuff that actually matters is the basic tools of your craft, and the stuff in your head. All the rest are props for the stuff in your head. And enough ego to put that stuff out there (or write posts like these).

So… that’s how I practice creativity. There are many ways, but that way is mine.

December 1, 2014

GDCNext Video: Practical Creativity

I know it seems like most all I post on this blog lately is stuff about speaking one place or another, and you always get three posts in a row: I will speak here, I spoke and here’s the slides… and a little while later, here’s the video.

I know it seems like most all I post on this blog lately is stuff about speaking one place or another, and you always get three posts in a row: I will speak here, I spoke and here’s the slides… and a little while later, here’s the video.

Well, not to be redundant, but here’s the video! Gamasutra – Video: Practical Creativity – A way to invent new kinds of video games.

This was the session I did at GDCNext about treating (game design) creativity as a skill that can be practiced, offering up tips and tricks on how to be creative.

November 24, 2014

GDCNext: Indie Grassroots Marketing video

At GDCnext I moderated a panel with Zach Gage, Rami Ismail, and Adam Saltsman on indie marketing. It was a fun session, made more so by the fact that they all walked into the room with one minute to spare before the session started (I was about to start pulling dev’s from the audience into the stage!).

It all worked out though, and now video is posted on the GDCVault! Enjoy!

November 21, 2014

Ten Years of World of Warcraft

Ten years of World of Warcraft. Well. So many thoughts.

Ten years of World of Warcraft. Well. So many thoughts.

WoW has always been a contradiction of sorts: not the pioneer, but the one that solidified the pattern. Not the experimenter, but the one that reaped the rewards. Not the innovator, but the one that was well-designed, built solidly, and made appealing. It was the MMO that took what has always been there, and delivered it in a package that was truly broadly appealing, enough so to capture the larger gamer audience for the first time.

Don’t get me wrong; that’s not a knock on it. If anything, it’s possibly the biggest game design achievement in all of virtual world history. After all, we’re talking about taking a game skeleton that was at that point already almost a decade and a half old, one which had literally had hundreds of iterations, hundreds of games launched. None of them ever reached that sort of audience, that sort of milestone, that sort of polish level.

After a decade and a half of refinements that didn’t do the trick, Blizzard came along and did what it does best: cut to the essence, capture the core fun elements in a game system, and make them accessible and appealing to the broadest possible market.

These days, so many more people have passed through the gates of Azeroth than ever played its antecedents that many don’t even know the deep wellspring sources from which it came. Most of the defining characteristics of WoW are from a long tradition that started around 1990. WoW represents the (perhaps final) evolution of the DikuMUD model.

Dikus are one of many branches off the MUD family tree, and one of the most popular. They defined the pure hack n slash model of MUD gameplay for many. Fixed classes, a level-based grind, clearly defined zones with monster farming and (eventually) quests. A healer, a tank, a nuker in the form of a magic-user, with a heavy emphasis on grouping. Little sense of world persistence; everything always resetting, repopping, respawning. Its audience, from the get-go, was “the kind of people who find adventuring and role-playing more fun than hacking,” to quote the announcement post that appeared on rec.games.mud in February of 1991.

A map of Midgaard, stock starting city in DikuMUDs.

Diku proved popular because of its simplicity: everything in a Diku game was hardcoded, which meant you got a working game out of the box. All content was in rigidly defined text files – almost like rigid database entries, with no support for scripts or conditionals. This meant swapping zones with another mud was generally trivial. The ease of hacking the barebones source code meant that a number of “codebases” or modified distributions became available: Alfa, Copper, Circle, ROM, and so on, each slowly advancing the capabilities of the basic experience. Diku spread like a virus across the gaming Internet, and the phenomenon of the “stock mud” was born, where you could log into twenty successive games and find yourself in the same starting rooms of Midgaard.

Many of the features we have come to expect from later MMORPGs didn’t originate from Dikus, it’s true. Housing in Dikus was a pale version of what was truly freeform in scriptable environments like MUSHes or MMOs. The flexibility of coding in LPMuds meant that most of the experiments that later became common features – from player-run guild systems to robust quests to procedurally generated environments – were first seen there, and then adapted into the far less flexible Diku codebases.

Dikus provided core inspiration to many of the earliest MMOs. Meridian 59 had its Diku players on the team. EverQuest was basically a love letter to Diku gameplay, inspired as it was very directly by the classic Sojourn MUD. Half of the original Ultima Online team was Diku players, though UO drew heavily from LPMud and even MUSH and MOO backgrounds as well, and therefore set off in its own, more sandboxy direction.

The Sims Online Newsweek cover

At the time that WoW was in development, there were two big MMOs launching. The Sims Online was featured on the front cover of Newsweek, and tipped to be the game that could take virtual online play mainstream. It had an enormous budget, and of course the power of the Sims brand. The other was my own project, Star Wars Galaxies – another powerful brand, but also far too short a development time and a quarter of the budget.

Both launched buggy, messy, rough, criticized for tedious gameplay. Both offered many innovations. But it didn’t matter: the juggernaut was coming.

WoW had been in development for a very long time, and unlike those other two titles, it was very much directly drawing its inspiration from EverQuest. EQ, the reigning king of Diku-style gameplay, was always resolutely about group combat. At the high-end of play, membership in “raids” (which at the time simply meant “big fights against tough monsters”) was the online teamwork game par excellence.

Rather than try to break new ground on features, WoW set out to instead collate the very best from every game it could, with a relentless focus on the fun. Where other games were chasing high-end graphics, they chose instead to aim low on technical requirements, opening up the potential playerbase considerably, while relying on stunning art direction that was initially decried as cartoony, but which was vivid and colorful and appealing in a way that the grittier other games were not.

And WoW indeed took many of the core features that other games had established, and by and large made them better through the alchemy of recombination and polish.

In Blizzard’s hands, raids became intricate puzzles to be solved, almost like teaching a large group a complex series of dance steps; a design idea drawn, perhaps, from boss stages in 2D bullet hell shooters. Given the influence that EQ raiders had on the WoW design team, it’s no surprise that to this day, raids are the engine driving WoW forward in so many ways.

The sheer colorfulness of WoW was a revelation; EQ had been relatively dark and grimy.

A related tool, instancing, had been invented clear back in the text mud days, but in WoW we saw it used to a degree that earlier MMO designers were reluctant to embrace. Seeing it as disruptive of the “worldness” of the game, myself and many other designers at the time pushed back against making too many dungeons into instances, arguing that the serendipity of meeting other players was core to the genre. But intricate raid patterns set up as patterns to solve can’t survive that sort of unpredictability, so WoW used instancing liberally, making high-end encounters feel ever more like embedded games or challenges in their own right. This had the interesting effect of reducing inter-guild contact, but strengthening the bonds within guilds as teams had to go through training regimens and practice sessions.

The realm versus realm combat that lay at the core of Dark Age of Camelot fit perfectly atop the Warcraft mythos; the underlying PvP flagging system was a variation on flagging systems explored in many muds, and of course famously and endlessly in Ultima Online. We forget, now, how contentious player-vs-player combat was, in those days, and how hard a design problem it was to make it feel seamless. It had been decided that the days of the PvP MMO were basically over, and yet WoW launched with what was basically a PvP MMO and managed to make it feel like a safe space for players.

The chat bubble system had been a massive design challenge on Star Wars Galaxies (chat bubbles had been used in 2D games, such as Habitat and The Realm, and There.com had done some extremely interesting stuff with them which I happily stole, but most MMO designers, alas didn’t play There); WoW cheerfully leveraged that work, but didn’t even use bubbles very much (plenty of mods exist now to enable them), as well as redoing their camera system during the beta to be surprisingly similar to SWG’s (probably convergent evolution).

Troll quest giver,

MMO Costume Contest at Dragon*Con 2008. Photo BY-NC Les Howard

Among the things left by the wayside were features that were proven. Gone were the richer pet systems that had driven so much engagement from players in earlier games. Player housing, past and future source of endless devotion (and revenue) in other games, absent. Never mind stuff like towns and politics and the like. Crafting took massive steps backwards from the heights it had been developed into in Galaxies or even Sims Online, and went back to being more like that in EverQuest. Even the robust character customization that we slaved over in Galaxies, a system which today is in every RPG on earth, was gone. In WoW, you basically looked how you looked, and early on the game was a sea of identical clones. The seamless world, which occupied so much technical effort from so many teams, was simply replaced with by-then-old-fashioned zones with network mirroring on the boundaries: a much simpler use-case than solving dynamic load balancing.

None of this is to minimize the effort this took; the work of selecting the right features to make World of Warcraft was precisely the hardest work there was. In the name of shorter sessions, greater accessibility, and easier entry, WoW cut away any “world-like” features in favor of Game, Game, Game.

In their place was one overriding feature, a true innovation that WoW lifted not from the rich and varied history of MMOs, but from the rising design tide in AAA games that was even then up-ending the first-person shooter: the quest-led game.

FPSes in the wake of Half-Life were moving towards today’s world of cinematic narratives intercut with vivid action; Blizzard had successfully made the cinematic campaign a centerpiece of its RTSes such as Warcraft 3. MMOs, however, were still fairly aimless affairs, always struggling with delivering even a coherent tutorial experience. Despite the name, EverQuest was far more about the fighting than stories – the questing in the title was really each player’s own quest for experience points. Even in Blizzard’s own RPGs, the Diablo series, we saw an MMO-like “hub-and-spoke” design, always pulling players back to one central town.

See that SWG waypoint? Way way way over there?

In WoW, despite the word “World” in the title, we saw linearity displace the free-roaming assumptions of the earlier games. Whereas games like Everquest 2 and Galaxies had invested heavily in waypoint systems that had proven to be powerful social and accessibility tools, WoW left this feature out because the game simply never had you travel a long way – the next goal was generally always within line of sight. Helpful symbols floating above characters’ heads, which had barely been seen in MMOs such as Asheron’s Call 2 (they originated in Blizzard’s own Diablo 2), were everywhere.

And the quests, while still built on top of familiar fetch or kill-n-monsters tropes, were also everywhere. A heretofore unthinkable density, much of it deeply humorous and rich with references to Warcraft lore for those who were willing to dig in. For the casual player, the experience of WoW was literally a series of quest completions designed to lead you along a pathway that had been carefully planned to constrain you, keep you always seeking the next glowy mark over an NPCs head.

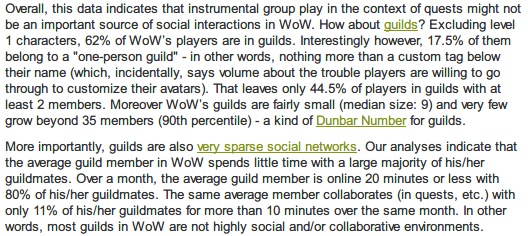

A snippet of academic analysis of play patterns in WoW in 2006 from TerraNova

This completely up-ended the old MMO pattern, which was more about hunting and gathering, interrupted with occasional quests. In WoW, leveling gameplay was instead about questing, with occasional hunting and gathering. Zones and their quests were crafted hand-in-hand, with the quest chains perfectly designed to lead you across the zone as it increased in difficulty, and birth you out into new zones just as you should reach the point of advancing to the next set of levels. It could only be done with an extravagant budget; indeed, WoW outspent all previous Diku games by a multiple of three or four. But it was incredibly powerful.

Sandboxy players found this to be a massive step backwards. In effect, there was hardly any open space; everything was dense, close together. The rich interdependence systems that were carefully crafted in earlier MMOs were absent. But players who had cut their teeth on single-player games had finally found a virtual world that was accessible to them, where they could “play alone together.” Paired with the power of Blizzard and the Warcraft brand, we watched WoW pick up more players in the first week than the entirety of the Western MMO market combined.

In some ways it was the apotheosis of this game design. Today, the influence is everywhere. To be an MMO has come to mean to be like World of Warcraft. The quest-driven advancement path. The tried and true combat mechanic and the raids. The interface must now conform, much as how FPSes on PC were forever condemned to WASD based on the popularity of specific games. WoW is now the template and the bar that everything must hit.

It’s not a hittable bar, for most. Almost no Western MMOs have ever been granted a comparable budget again, and of course these days, you have to actually compete with ten years’ worth of WoW expansions and additional content and refinements. Slowly, some of those omitted features have crept back in – WoW’s class system is today a much more flexible hybrid class-and-skill system that offers ample personal expression. Given time, the game economy re-acquired some of the characteristics of the sandboxy games – but not too much, in order to retain the focus.

I got your sandbox MMO right here

And the game that was once called, by me and many others, “the least social MMO on the market,” is now the virtual home away from home for millions, as network effects, familiarity, and its ongoing dedication to a great user experience above all makes it makes the place we always return to. It is the genre king, and likely will never be toppled by a game like it, as long as investment in it continues. We likely will not see true reinvention come to the space until there are massive changes in content delivery, such as near-unlimited cloud server power, or virtual reality displays, that both permit and force truly different experiences to be created.

The space it entered as a competitor is largely “dead” in the sense that WoW takes up all the oxygen in the room. Experiments in virtual world design began to dry up, to curtail their ambitions to being nibbles around the edge of WoW’s design. Like toothpaste squeezed out of a tube, the design qualities of sandbox games ended up finding their expression elsewhere, to great success. Their children served as the basis of genres, from Facebook farming games to DayZ-style survival games to the true heir of the MUD tradition: Minecraft, a virtual world based on simulation and crafting, where users run their own worlds and script and build adventures and are basically questless.

It’s just that no one calls them MMOs anymore. That title is reserved for World of Warcraft, and those largely similar games that strive to topple it from its seat. Its influence is such that it now defines the genre it refined. It is the best Diku ever made; the best combat MMO ever made; the thing to which everything like it will ever after be compared. World of Warcraft effectively made MMOs perfect, and in the process, it killed them.

November 19, 2014

Yiynova MVP22U v3 review: 22 inch Cintiq alternative

Quite a while ago I wrote a review of the Yiynova MSP19U, a Cintiq alternative tablet monitor. I was pretty pleased with it, but it did suffer from relatively low resolution and from a TFT screen with pool viewing angles for color reproduction.

The Yiynova MVP22U V3. Plus a sneak peek at some game artwork for an upcoming game of mine.

Now I have a review for you of the upgrade model, the Yiynova MVP22U(V3) Tablet Monitor . It’s actually the third version of this monitor, as you can tell from the name. I have owned the Yiynova MSP19U+ Tablet Monitor

. It’s actually the third version of this monitor, as you can tell from the name. I have owned the Yiynova MSP19U+ Tablet Monitor , the MVP22Uv1, V2, and now V3 (for somewhat complicated reasons, see below). The V3 is a very noticeable upgrade over the V2, which in turn was a big step over the V1. This is a full HD 1920×1080 tablet monitor — no touchscreen, stylus pen only, with 2048 degrees of pressure sensitivity.

, the MVP22Uv1, V2, and now V3 (for somewhat complicated reasons, see below). The V3 is a very noticeable upgrade over the V2, which in turn was a big step over the V1. This is a full HD 1920×1080 tablet monitor — no touchscreen, stylus pen only, with 2048 degrees of pressure sensitivity.

The earlier models: V1 and V2

I was an early adopter of the V1, which does not seem to be available anymore. The V1 suffered from the fact that the large screen was a TFT, like the 19 inch model — even close up, you would see color issues resulting from the viewing angles on a TFT screen, just because the 22″ screen was so big. There were also font rendering issues caused by the drivers for the monitor itself. I returned my V1 in favor of a V2 (which is) when that came out, because of a desire to upgrade from the TFT screen and because of the font firmware patch. Panda City generously offered to swap the monitor out originally for the firmware patch, then let me pay the difference to get an upgrade.

(which is) when that came out, because of a desire to upgrade from the TFT screen and because of the font firmware patch. Panda City generously offered to swap the monitor out originally for the firmware patch, then let me pay the difference to get an upgrade.

The V2 added a firmware patch for the font issue, and also upgraded to an IPS panel. The panel was pretty good, but only offered a VGA connector. This meant that you had to use an adapter to use it on a modern video card with digital outputs such as DVI. I ran it with a DVI to VGA adapter. I still had font issues, though they were improved; it may be that the issue was around the VGA conversion. The IPS panel solved the color and angle viewing issues. The improved firmware also introduced better pen tracking particularly for slow lines.

added a firmware patch for the font issue, and also upgraded to an IPS panel. The panel was pretty good, but only offered a VGA connector. This meant that you had to use an adapter to use it on a modern video card with digital outputs such as DVI. I ran it with a DVI to VGA adapter. I still had font issues, though they were improved; it may be that the issue was around the VGA conversion. The IPS panel solved the color and angle viewing issues. The improved firmware also introduced better pen tracking particularly for slow lines.

Hardware

The monitor now uses a DVII connector. The cable splits near the end with a USB offshoot that needs to be connected for the pen tablet functionality to work. It is still a cable that is permanently attached at the monitor side, alas; I am running it to an extender cable with a DVII extender, and also running a USB extender.

This is in anticipation of switching from the built-in VESA stand to a monitor arm. The VESA stand permits a wide range of tilt, but dragging it around on the desk is getting old.

The monitor does have eight hotkeys at the top. These can be mapped to any number of things, including opening software packages, keystrokes, media control, and more. These mappings are not per software package, however. The buttons are also a bit hard to reach.

Display

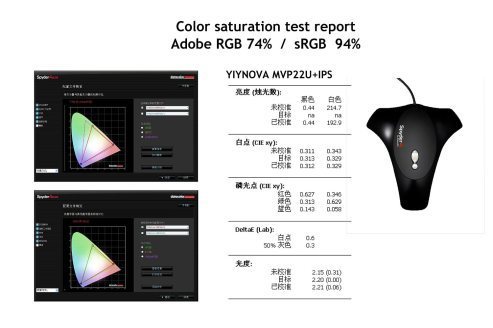

Yiynova’s flyer on the improved panel

V3 now has an even better IPS panel than the V2, with improved color gamut. Out of the box, a calibration check at lagom.nl’s monitor testing site showed dead-on color accuracy, sharpness, black levels, and gamma. Basically, it crushed every test but one. The only issue was on the inversion test — slight flickers on 1 and 7b, noticeable on 3. (For comparison, my HP ZR22w flickered slightly only on 4a and 4b; my Viewsonic only on 4b).

In comparison, the V2 flunked the sharpness test (oversharp, and there was no sharpness adjustment in the OSD), and flickered strongly on patterns 3 and 7b. It also exhibited a slight reddening on the full-screen purple test; the V3 does not. Unlike the 19U and the V1, both of which ran cool out of the box, the V3 was perfectly calibrated from the get go.

As the V3 is a new panel, it also has a new OSD. This OSD has more or less the same options as the V2 did:

Brightness, contrast, gamma

Color temp, and R, G, B

A sharpness setting rather than clock and phase (since it is digital)

Horizontal and vertical OSD position, and language (it supports a lot of languages, too).

The older V2, given the VGA connector, had phase, autoadjust, and horizontal and vertical offset for the screen. These don’t apply with a digital connection.

Pen and drawing

Three generations of Yiynova pen

The various Yiynova models, going back to the 19U, have always had great pen tracking. There have been a few generations of pen and some firmware adjustments to pressure sensitivity, but it has always been great. The V3 has 2048 levels, and no tilt support. I have no issues whatsoever with line straightness doing a ruler test. There is no “waviness” from imprecise tracking behind the screen. There is no jitter outside from that of your own hand. The tablet was perfectly calibrated all the way to the edge of the display, out of the box — actually slightly better than the V2. I am able to draw literally to the exact corner pixels, at all four corners. If you haven’t drawn on a Yiynova yet, it’s basically excellent, and quite comparable to Wacom, barring tilt.

At this point I have been through many Yiynova pens.  They all require a AAA battery, unlike Wacom pens. None of them have erasers. None of them support tilt. They all have a rocker button that the drivers let you map.

They all require a AAA battery, unlike Wacom pens. None of them have erasers. None of them support tilt. They all have a rocker button that the drivers let you map.

Original 19U pen: This is the one that came with the 19U. Getting to 2048 required pressing pretty hard. Also, the rubbery “sleeve” was not the sturdiest design. I think this pen has been phased out completely now. A second 19U style pen came with the V1. I don’t have to press as hard as the original. More sensitive to light strokes — easier to make light lines with.

v1 22U pen (a slightly earlier version of P2H tablet pen

): I don’t have it anymore, but I had to press hard though not as hard as the 19U pen. It felt “stiffer” across the board. These pens introduced a whole new pen barrel, with a shiny glossy plastic for most of it and a rubberized grip area. The whole thing is rather sharpie-like, but also much sturdier than the original pen.

): I don’t have it anymore, but I had to press hard though not as hard as the 19U pen. It felt “stiffer” across the board. These pens introduced a whole new pen barrel, with a shiny glossy plastic for most of it and a rubberized grip area. The whole thing is rather sharpie-like, but also much sturdier than the original pen.The P2H tablet pen

is the current version of that pen, after it was revised based on feedback from artist Ray Frenden, and the drivers were tweaked as well, to adjust the pressure curve. Sensitive to light strokes, and I don’t have to press anywhere near as hard to reach 2047. Now, this is of course also paired with the new firmware in the tablet itself. The reduced jitter and improved tracking likely makes a difference here too.

is the current version of that pen, after it was revised based on feedback from artist Ray Frenden, and the drivers were tweaked as well, to adjust the pressure curve. Sensitive to light strokes, and I don’t have to press anywhere near as hard to reach 2047. Now, this is of course also paired with the new firmware in the tablet itself. The reduced jitter and improved tracking likely makes a difference here too.The new V3 has both the P2H and the new P2X Premium Tablet Pen

. The P2X pen performs identically to the earlier pen, but it has a much better fit and finish; the pen now has a taper much like a traditional ink quill, bulging before the nib. This enables the part where you grip the pen to be thinner. The exterior is now a slightly tacky material that feels great. There’s also a light, supposedly, to inform you of low battery, but I have never seen it come on (batteries last forever in these pens).

. The P2X pen performs identically to the earlier pen, but it has a much better fit and finish; the pen now has a taper much like a traditional ink quill, bulging before the nib. This enables the part where you grip the pen to be thinner. The exterior is now a slightly tacky material that feels great. There’s also a light, supposedly, to inform you of low battery, but I have never seen it come on (batteries last forever in these pens).All in all, the new pen is just great. Right now, the V3 comes with one of each of the P2X and the P2H.

Note that pens do have some slight variation. The new P2H that came with the V3 is stiffer than the one I had with the V2; it takes more pressure to reach 2047 (max). However, it registers very soft strokes, at sensitivity around 8-15. I have two P2Xs, because I bought one standalone for the V2 when they came out. One of them is slightly more sensitive than the other — my lightest stroke registers at single digits with one (like the P2H), and in the teens with the other. Both seem to take about the same to get to 2047.

Drivers

The box included a CD with new 8.0 drivers. They are apparently mostly for compatibility with Windows 8. I had the 5.02g drivers installed previously, and the tablet worked instantly without anything needing to be installed. But I decided to try the new drivers anyway. I am running on Windows 7, 64bit.

I found that the 8.0 driver required me to uncheck “Supports Digital Ink” on the Info tab. Otherwise, the pen would not work unless the control panel was open and on the Pressure tab. I could sketch in the pressure tab, but if I switched tabs, I lose the pen altogether.

I did try going into Tablet PC settings, and it showed that my main monitor (not the tablet) was the one with the pen. But I couldn’t change it to the MVP22U because that control panel would not recognize taps on the screen. It didn’t matter if Supports Digital Ink was checked or not.

I did not have problems using the ink tools in Office.

Mapping express keys to Common function -> POP MENU worked, but I was not able to make the pop menu work on the tablet. It worked correctly with the mouse on the other screens. If I opened it while the cursor was on the tablet, it forced my mouse to jump to one of the other screens completely, and I was unable to move the mouse to the tablet (it was like it wasn’t there). If I tried using the pen to tap it instead, any tap just closed the menu.

The pressure sensitivity works just fine in Photoshop, Manga Studio, Inkscape, Pencil2D, and Sculptris. It works with FireAlpaca, but you need to set it up: If you go into File->Environment Setting and set “Brush Coordinate” to “Use Mouse Coordinate” instead of “Use Tablet Coordinate (recommended)” both the line and the offset are fixed.

It did not seem to work out of the box in Sketchbook Pro. I could swear it used to under the old drivers, so I will have to investigate that more.

I checked with Panda City, and they told me that 5.02g is actually the recommended driver for Windows 7. Note that 5.02g is NOT on the CD they send, so if you run Win 7, you should download that version from their site. I will probably try reverting back and running thorough tests to see if there is any difference.

Fit and Finish

All three of the 22Us have shared the same chassis more or less. But something in the manufacturing process has clearly improved. In the V1, the buttons at the top actually had light leakage behind them. In the V2, they were slightly loose and wobbly. On the V3, they are just solid, and I see no light leakage.

The monitor is white, with a fairly big bezel, particularly on the bottom. The glass is held on with little clips that protrude slightly, so there is a bit of a lip all the way around the very edge of the monitor. One nice thing is that the glass goes edge to edge, so there is no border for your pen to hit when you draw off the edge of the actual screen. It does get squeaky with the plastic pen nib and the glass, though. Some modders have tried making felt nibs out of the Wacom ones, and it seems to work, but I have not tried it myself.

Extra Stuff

The V2 came with a couple of monitor adapters. The new version comes with three: one each for HDMI, VGA, and MiniDisplayPort/Thunderbolt.

The V3 also came with Yiynova Artist Gloves , a pen stand

, a pen stand , a P2X pen and a P2H pen, both with the new hard plastic case with stands (the V2 only had relatively flimsy thin plastic boxes for the pens). There are extra nibs and nib removal tools included with each, so now I have a ton of them.

, a P2X pen and a P2H pen, both with the new hard plastic case with stands (the V2 only had relatively flimsy thin plastic boxes for the pens). There are extra nibs and nib removal tools included with each, so now I have a ton of them.  This may be a holiday promotion only. Right now, list price for the monitor shows as $1200, but it’s on sale for $999.

This may be a holiday promotion only. Right now, list price for the monitor shows as $1200, but it’s on sale for $999.

Customer Support

In short, The Panda City (the US distributor for Yiynova) has really phenomenal customer support.

My V2 had developed a “pixel crawl” issue over the course of almost a year of usage, where the monitor would go out of phase, and pixels seemed to “wiggle.” It also seemed to regularly “forget” its correct phase settings for auto-adjust — auto adjusting would even send it to numbers that weren’t valid sometimes (outside of the 1-100 range). Talking with Panda City, we concluded it was some form of electrical interference, but could not pinpoint it. They once again offered to swap out the monitor, and once again allowed me to upgrade.

I can’t say enough about how phenomenal Panda City’s customer support is. They are extremely attentive, and have sent me things like a new pen holder when one broke. I generally get an answer within an hour, even on a Sunday night. They have also been very open to discussions about driver changes, firmware bugs, and so on, relaying my feedback backto the team in China.

The V3 comes with a two year warranty where the earlier V2 came with a one year.

All in all, I am contemplating making this my main monitor now. They really have perfected it; about all that I could wish for would be a few more hotkeys, a nicer chassis, and maybe little labels for the buttons on the front or side rather than the back.

November 13, 2014

Social media is broken

Thinking on Wil Wheaton’s well-intentioned essay, here are some things that we know.

Thinking on Wil Wheaton’s well-intentioned essay, here are some things that we know.

Anonymity is usually problematic. But the real issue isn’t anonymity. It’s actually “lack of persistent identity.” Anonymity can serve as a cover for bad behavior, because humans are deeply situational when it comes to ethical choices. We fall prey to disinhibition readily, and the biggest reason is “we don’t think we will interact with these people again.” It’s repeated interactions that drive trust, you see, and we behave well because we expect to be treated well in the future.

Anonymity can be very important for the marginalized, for whistleblowers, etc. But within their communities of trust they build reputation, including pseudonymous reputation. The real issue is feeling free of reputation, which equals feeling free of consequence. That is where bad behavior comes from.

Scale is bad. At large scale, positive reputation tools cease to work because they lack locality or spread. You can feel free to be rude to a stranger in a huge city because you really don’t have any expectation of future interaction. The bigger the forum, the worse behavior problems get, as people splinter into smaller social groups, and only care about their reputations within that group. People only really need the positive approval of their peer group, or their repeated interaction group. Arguably, an anonymous environment small enough for people to get to know each other might actually have better behavior than an environment with strong identity and huge scale.

Downvoting and other forms of negative feedback reputation systems, lead to bad social behavior. They encourage downvote campaigns or “brigading” as a form of battle against positive reputation; they encourage non-persistent identity because it’s easier to wipe an identity than it is to build one up. So a downvoted identity will a) feel free of consequences and b) likely move to anonymity through the creation of alternate identities, from which it is a small step to sock-puppetry. Further, downvotes can be interpreted perversely as an incentive ladder.

At large scale, the splintering of groups into smaller identities always leads to conflict between groups, because identity competition is part of the process of identity definition. One defines an identity in reaction to an Other. The fruitful path is to find meta-identities that both groups belong to; “I am red, you are blue, we are both colors together!” Should red be defined out from being a color, it becomes radicalized as a group, and members more likely to stop caring about their reputation not only with blues, but also with the larger color group within which it exists.

Given humans’ preference for confirmation bias over truth, and emotionally-based rather than logic-based decision-making, tribalism and identity creation around those are inevitable. However, if the various subgroups fail to mingle sufficiently to sense a larger mutual identity, we start to get polarization via the Othering process, followed by first verbal, then physical violence. When this occurs, good fences make good neighbors.

Where these fences do not exist, there is a real risk of words traveling out of social contexts and being radically misinterpreted by another group that literally “speaks another language” in terms of the semantic freight. What is considered proper or acceptable behavior can shift dramatically from venue to venue, including even to the point where subgroups may develop social practices that a larger, encompassing group may consider utterly abhorrent.

Mediators who move between contexts and are familiar with the language used on both sides, or who use carefully framed “diplomatic” language that is couched in incredibly mild terms is the typical solution here. Another solution, explored in a few online games, is to literally not permit communication across the conflict divide, because it’s better to have open conflict without taunting than to have taunts and insults in the mix.

This matters because all of these lessons, which are well-established across many fields, are routinely ignored by social media designers. I leave it as an exercise for the reader to think of popular social media which make these design mistakes:

unpartitioned, over-large, or otherwise lacking in “good fences”

relies on anonymity or pseudonymity without a parallel structure for building up persistent reputation

encourages downvoting, brigading, or other negative feedback loops

fails to provide meta-identity structures that provide common ground between groups

drive intentional tribalism

promote filter bubble effects and polarization

The relevance to recent events is also left as an exercise.

Old stuff you may want to read: On Trust parts one, two, three, side note, three-point-five; and this post on reputation systems.

November 3, 2014

GDCNext 2014: Practical Creativity slides

Today I delivered a lecture at GDCNext that was my tips for “practical creativity.” Basically, it’s a collection of techniques, habits, and ways of thinking drawn not only from lots of reading and research into creativity in general, but also my experience in visual, writerly, musical, and ludic arts. It touches on breaking down craft elements in games, on choosing ambitious and unusual themes, on simple lifestyle habits, on the power of “scenius” and collaborators, and much more.

Today I delivered a lecture at GDCNext that was my tips for “practical creativity.” Basically, it’s a collection of techniques, habits, and ways of thinking drawn not only from lots of reading and research into creativity in general, but also my experience in visual, writerly, musical, and ludic arts. It touches on breaking down craft elements in games, on choosing ambitious and unusual themes, on simple lifestyle habits, on the power of “scenius” and collaborators, and much more.

I wanted this to be deeply practical. I myself have been using these methods a lot in the last year — maybe slacking a lot on the “get regular exercise” one. And it’s been very fruitful for me, almost too fruitful, pushing my prototype hit rate over 90%.

I really wanted to emphasize the fact that in all this, the craft is inseparable from the art, too. Creativity in craft drives creativity in art, and vice versa.

The talk was recorded and no doubt will appear, given time, on the GDCVault. In the meantime, here are the slides, presented without notes or anything. So you’ll miss out on the many times I interrupted the presentation and put the attendees directly on the spot to create new ideas on the fly using the techniques presented. My favorites: the game that actually taught dancing in psecific dance styles like the tango, and the game about learning how to ride a bicycle.

The eagle-eyed may spot a slide with the description of a new boardgame of mine that is testing really well so far, a romance novel game…

October 13, 2014

Gamasutra on the indie economics talk

Yesterday Greg Costikyan and I did an on-stage conversation at Indiecade about the economics of the indie market. It was pretty wide-ranging, with discussions of Rochdale cooperatives, performing rights organizations, designing games that can be hobbies rather than disposable content, and more.

Greg Costikyan and Raph Koster speak about indie economics! @IndieCade -f- @SwedenGameArena @HogskolanSkovde pic.twitter.com/dVHzWRhQVb

— Martin Hagvall (@studygames) October 12, 2014

As you might expect, there was no easy answer. Otherwise all the usual suggested tactics would have worked better for Costikyan, who deadpanned right away: “I have founded two failed companies. Follow my advice and you too can fail.” Koster, who despite having sold a successful company, noted “You can be successful business-wise, and still not achieve what you want in games.”

Gamasutra has a write-up that captures some of it, but not all. It was, perhaps, a bit of a depressing conversation. Among other things, we discussed the fact that there’s probably an oversupply of indies now, and that the rising market landscape means that some sorts of games — indeed, many of the most exciting kinds of games that have arisen in the last few years — might not be all that economically viable.

As far as the rest of IndieCade — it was inspiring and exciting. A wide variety of games of all sorts were being showcased, from VR to tabletop. It was my first time, and it felt like a pretty tight-knit community, but very welcoming. I wish I had been able to go all four days.

September 24, 2014

Indiecade: A conversation on indie economics

Greg Costikyan and I will be doing an on-stage conversation at Indiecade on the subject of the economics of the indie market. This is driven by the various discussions we started having around GDC time in the spring, including his rant at GDC, and my follow-on article on the directions game industry finances are likely to take, which was also reprinted at Gamasutra and had a great discussion thread over there.

Greg Costikyan and I will be doing an on-stage conversation at Indiecade on the subject of the economics of the indie market. This is driven by the various discussions we started having around GDC time in the spring, including his rant at GDC, and my follow-on article on the directions game industry finances are likely to take, which was also reprinted at Gamasutra and had a great discussion thread over there.

Plenty has changed already — as if the power of YouTube as marketing channel weren’t already very evident, we also have the new Steam curation system coming into play. And the fact that the practice of paying for YouTuber videos is alive and well, with costs from $500 on up for a review, is sure to come up. I note that there are not one, not two, but three sessions on indie game economics at Indiecade, so this is clearly all on people’s minds.

It’ll be on Sunday the 12th at 1:30 in the Ivy Theater. Hope to see you there!

September 23, 2014

Speaking on “Practical Creativity”

I’ll be talking at GDCNext in LA in early November about “practical creativity.”

Over the last couple of years, I have had no commercial masters over my creativity. Oh, I’ve done some consulting and whatnot, but the vast majority of my time has been on projects that I am pursuing out of pure passion, a desire to make them. And I’ve had an incredibly prolific period; the most prolific of my life, actually.

One of the things that has been really striking about it for me is the high hit rate on prototypes. Some strange alchemy between the indie strivings towards art and the accumulated lessons from game grammar and “formalist” thinking, between reading up on human psychology and mathematics, has created for me a toolset that is in some ways very practical, even dull. Very straightforward and easy to share. So, I’m going to!

Practical Creativity

Raph Koster | Designer, Independent

Format: Lecture

Track: Design

Pass Type: All Access Pass, GDC Next PassIt’s a world of clones, of derivative ideas, of repackaging games in genres. It can be hard to be creative. And all too often, creativity is treated as a magical talent that few have, when it’s actually a skill that anyone can learn and that improves with practice! Come learn what science tells us about creativity, and practical straightforward steps that any game designer or developer can make use of in order to get more creative. We’ll actually try these things out in the talk, and I promise every attendee will leave with a brand-new game idea, never before seen.

Takeaway

Attendees will learn what “creativity” is currently thought to be, and specific tools and tricks for making their games more creative. We’ll even try to be creative during the actual talk!