Raph Koster's Blog, page 14

May 13, 2014

Monkey-X

Monkey-X is my current favorite language for doing game prototypes and even full projects. It isn’t at all widely known, and has more than a few rough edges, but I still find it congenial and thought I’d share so that more people will give it a try.

When I went looking for something to code in, I had the following criteria:

Get stuff on screen in under an hour. Ideally, under ten minutes.

Output to as many platforms as possible.

Web, because that is useful for accessibility, Facebook, demos, and more.

Desktop, because that’s where midcore and core gamers still live.

Mobile, because the whole world is moving to touch.

Avoid porting. Porting is tedious and expensive. Yes, you get the advantage of maximizing use of the hardware, but the fact is that there’s a lot of headroom on hardware these days.

A community large enough to supply libraries for things I don’t want to write myself. I am no great shakes as a coder, you see.

Syntax that doesn’t make my eyes cross (looking at you, Objective C).

Garbage collection. Why? Because I always mess it up, and then it gets in the way of being productive.

Monkey-X met these criteria, though the community is still pretty small.

Monkey outputs to desktops (Windows, Mac, and Linux). It outputs to mobile (iOS, Android, Windows Phone). It outputs to the Web in both HTML5 and Flash. It does XNA, it does Playstation Mobile (Vita!)… the way it works is by creating a native project for each, as long as you have the toolchain on your dev machine. So after hitting compile, you actually have a Visual Studio project, an XCode project, and so on.

It’s also $99 and mostly open source, though you certainly want to spend some extra money for JungleIDE.

There’s GL (ncluding WebGL), Box2d, physaxe or Chipmunk for physics, Flixel, Particle Candy, a pretty nice community framework called Diddy, a few others (Playniax, Ignition, etc), several GUI libraries (though none are yet desktop-app level, they are mostly aimed at games), and so on. Nowhere near what there is for the Asset Store in Unity, though.

Language-wise, it’s a descendant of the Blitz family of languages, which I have used off and on for years now. It’s object-oriented, supports reflection and interfaces, you can load in external code, and even add your own targets if you are willing to dig in deep.

I looked a lot of other languages when I did this research back in 2013. My test case was “make a Bejeweled grid,” because it is so incredibly simple.

Unity is of course the big gorilla. Enormous community, tons of support, and it does everything. But it does 2d and rapid prototyping poorly (it has quite a learning curve), and most of what I want to do right now is 2d. I can stage up a gorgeous outdoor FPS game in under an hour in Unity. Making a grid with gems on it, though, took me hours. I’m sure I could do it faster, given more practice, but the fact is that doing 2d in Unity is working against the grain. Unity is also much more expensive than everything else if you plan to ship anything with it. I am sure that at some point, I will have to bite the bullet and dive in, given that Unity is well on its way to having a monopoly on game development.

Gamemaker is way more robust than many give it credit for. At GDC, one of the people from there did the Bejeweled test in under ten minutes. You do have to work inside of the integrated editor and tool, like Unity, but you can pretty much do all the work in GML, their scripting language. You need the Pro or Master Collection ($799) to get all the target platforms, though.

Corona is basically Lua. It’s great, and I am quite comfy in it, but it doesn’t do desktop or web.

Loom is done by folks I know, actually, and is pretty slick. But it is very directly aimed at ex-Flash people, mimicking APIs and the like, and I actively disliked what I saw of coding with Flash while doing social games.

Some stuff I didn’t look at too closely:

Marmalade has annual fees; you write in C/C++.

There was just writing directly with Cocos2d-x.

Moai is also out there; it’s like Corona, only open source and with more targets, but less usability.

Monogame, which is somewhat more low level than the above.

SDL, which is WAY more low level than the above.

May 11, 2014

The Sunday Poem: Afternoon Joggers

It has been a very long time since I posted a Sunday Poem. That is because it has been a long time since I wrote a poem. But here is one that popped out the other day.

Afternoon Joggers

The way they run, struggling against invisible wind,

Great gusts in their chests buffeting them

Like hurricaned pines.

These flagellates billow out each afternoon,

Tilt up slopes I cannot see, at windmills I will not.

They sigh in each night.

This is their duty to themselves, their dream

Of spasms and joints and jolt, their Sisyphean journey

From wind sprints to wind sprites.

This, however, saves you from the one that my mom found today, that I wrote for her for Mother’s Day in the third or fourth grade.

May 7, 2014

The Financial Future of Game Developers

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the financial future of developers.

The supply chain for creative work

To go back a ways, back in 2006 I suggested that you could look at the winding path a piece of media takes to the public in this way:

A funder of some sort ponies up the money so that a creative can eat while they work. Sometimes this is self-funding, sometimes it’s an advance, sometimes it’s patronage.

A funder of some sort ponies up the money so that a creative can eat while they work. Sometimes this is self-funding, sometimes it’s an advance, sometimes it’s patronage. A creator actually makes the artwork.

A creator actually makes the artwork. An editor serves the role of gatekeeper and quality check, deciding what makes it further up the ladder. They serve in a curatorial role not just for the sake of gatekeeping but also to keep the overall market from being impossible to navigate, and to maximize the revenue from a given work.

An editor serves the role of gatekeeper and quality check, deciding what makes it further up the ladder. They serve in a curatorial role not just for the sake of gatekeeping but also to keep the overall market from being impossible to navigate, and to maximize the revenue from a given work. A publisher disseminates the work to the market under their name. A lot of folks might think this role doesn’t matter, but there are huge economies of scale in aggregating work; there’s boring tax. legal, and business reasons to do it; it serves brand identity, making the work easier, to market…

A publisher disseminates the work to the market under their name. A lot of folks might think this role doesn’t matter, but there are huge economies of scale in aggregating work; there’s boring tax. legal, and business reasons to do it; it serves brand identity, making the work easier, to market… Marketing channels make it possible for the artwork to be seen by the public: reviews, trade magazines, ads. This is how the public finds out something even exists.

Marketing channels make it possible for the artwork to be seen by the public: reviews, trade magazines, ads. This is how the public finds out something even exists. Distributors actually convey the work to the store’s hands. This role functions in the background, but it’s absolutely critical. There’s a lot of infrastructure required.

Distributors actually convey the work to the store’s hands. This role functions in the background, but it’s absolutely critical. There’s a lot of infrastructure required. Stores then retail the packaged form of the artwork to the end customer. Stores have their own branding task, and likely serve as a curatorial and recommendation engine all over again, this time trying to find the right fit for the customer.

Stores then retail the packaged form of the artwork to the end customer. Stores have their own branding task, and likely serve as a curatorial and recommendation engine all over again, this time trying to find the right fit for the customer. The audience then gets to experience the work.

The audience then gets to experience the work. Re-users then take the creation and restart the process in alternate forms; adaptations to movies, audiobooks, classic game packages, what have you.

Re-users then take the creation and restart the process in alternate forms; adaptations to movies, audiobooks, classic game packages, what have you.One consequence of the changes in the industry has been to consolidate more and more roles into the hands of fewer organizations.

At different times, and for different media, different people have held ownership of chunks of this pathway. For example, an indie today handles both their self-funding and their creation. There are popular writers, like James Patterson or Robert K. Tanenbaum, who actually outsource the creative part. EA’s big business initiative that led them to dominating the game landscape for quite a while was that they decided to build their own distribution network to retail long before anyone else (there used to be independent videogame distribution companies that sat between publishers and retail).

Consolidation strikes

All of these roles still exist, and likely they will always exist. It’s just that as the landscape changes, some people start to wear multiple hats, fulfilling more than one role.

Let’s take the Apple App Store as an example.

You likely fund yourself.

You like make the game yourself.

The App Store acts as editor, though they have a much lighter hand than traditional editors have had.

If you self-release, you’re supposedly the publisher, but really, it’s more like Apple is.

Apple also controls the most important marketing channel, which is Apple’s own front page, charts, and features.

Apple is the distributor, as is the case with all App Stores.

Apple is the storefront.

The player is the player, hurray!

Alas, the re-user is often a cloner.

A console is really a hardware front end to a digital publisher/distribution network/storefront. Call it a “metaconsole.”

One consequence of the changes in the industry has been to consolidate more and more roles into the hands of fewer organizations. There are less publishers. Less distributors. Less marketing channels. Less stores. About the only thing there are more of is consoles, and that’s because what we call “a console” isn’t:

Playstation 4 & Vita

XBox One

WiiU

Nintendo 3DS

Ouya

Amazon Fire TV

iOS App Store

Google Play

Steam.

These are all functionally the same, as far as a game developer is concerned. Today, a console is really just a hardware front end to a digital publisher/distribution network/storefront. Call it a “metaconsole.” Even with this proliferation of ecosystems, we have a net loss in diversity and complexity of the overall landscape.

Less, generally speaking, is bad. It means fewer outlets for a creative, and fewer choices for a consumer. It’s great if you are one of the few. But in practice, market dynamics tend to clean up this sort of messy proliferation over time.

Money wins out

While the landscape is wild and crazy, creativity reigns. Wacky ideas get tried. Some of them hit. Genres are created.

So what happens when markets mature? Well, whoever had the largest piles of money tends to start swallowing up more roles. And they get entrenched, and they stay entrenched until there’s a massive enough shift. In those mature markets, creators have to compete on money. Not creativity. Not innovation. Money. Money in the form of marketing spend, in the form of glossy production values, in the form of distribution reach.

So what happens when markets mature? Well, whoever had the largest piles of money tends to start swallowing up more roles. And they get entrenched, and they stay entrenched until there’s a massive enough shift. In those mature markets, creators have to compete on money. Not creativity. Not innovation. Money. Money in the form of marketing spend, in the form of glossy production values, in the form of distribution reach.

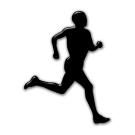

In a different talk back in 2011, I doomcast indies. Basically, these trends were plenty visible then, and I said that I was very worried about indies because as costs rose, they wouldn’t be able to compete in terms of marketing dollars and glossiness. They might still make great games, but they would rapidly end up beholden to The Man again, as the need for deep pockets rose. It’s a recipe for hollowing out the middle, you see. Midsized devs have to either become big ones, be subsumed by big ones, or slip down to become small ones, who probably don’t make a living (but might get a stroke of luck and win the visibility lottery, as viral hits do). Those who have the money become more and more predatory, as in this parodic conversation between a dev and a mobile game publisher that was making the rounds yesterday.

In the long run, though, this is bad for the ecosystem owners. Right now, as it always is in mature markets, the conventional business wisdom is to move to a blockbuster mentality. Place few bets, spend like utter mad against them (500m for Destiny, is the current news item, but in the past we have seen the same story for GTA, SWTOR, WoW, Final Fantasy, and Sims Online. Even for Cityville). The risk, of course, is that by reducing the portfolio diversity to that degree, a few failed blockbusters in a row topple the whole organization. Any structure that depends solely on blockbusters is not long for this world, because there is a significant component of luck in what drives popularity, so every release is literally a gamble.

So a wise org is always trying to keep the fringe alive through good curation and hedging bets.

Unfortunately, in these self-publishing days, where all the risk has been offloaded as much as possible to the creator who self-funds, I think there are some new dynamics at play.

Some dev makes a game and puts it up on the store. Its mere existence provides real, tangible financial value to Apple — after all, the ads for iPads are all about the apps, and even adding one more useless one to the 7000 that appear each day is putting another brick in a large edifice, giving Apple another number to trumpet.

But the median game uploaded to the App Store makes zero dollars.

It certainly doesn’t cover its costs. If it was wildly profitable it probably became so with big financial backing because the market is more hit-driven. So the value goes to the company that owns the game, not down to the individual developer, except in rare cases like a Flappy Bird. And that rare case is what the vertically integrated “consoles” count on — because it instills dreams and hopes that you, too, could make that happen. And you could, just like you could go to Vegas and win ten million bucks on a single quarter.

Basically, at the bottom end of the market you have devs who get to be creative but not eat. At the top end you get devs who get to eat but not be creative. And there is no middle.

The old solution?

In 2006, my prediction was today’s world, and I offered up as solutions the following:

build direct relationships with your audience

celebritize yourself

create games that are services, to lock in that audience

develop alternate revenue streams, by creating games that are IPs that support downstream uses of the IP

Get someone else to fund, but make yourself the creator, the editor, the distributor, the re-user.

This is all perfectly good advice. Excellent, even, considering it was given in 2006. But here’s the rub.

Some people aren’t good at all these roles. And even if they are, the more they have to pay attention to the non-creative aspects, the more it is likely to affect their creativity. They start not pursuing a wild idea because they see no market for it. They start changing their game design to make the game be a service even though it’s working against the grain of the game. And lastly, it means being a business entity, to a much larger degree — which almost certainly means that someday you will lose control of it.

The fact is that the old solution does work. But it also returns us to the cycle, to a world where the massive indie explosion we saw doesn’t exist.

And don’t go thinking that “Oh, but Sony is good this generation!” or “Steam is on the developers’ side!” The fact of the matter is that the role molds the organization. The more Steam becomes a metaconsole, the more it acts like one.

A modest proposal

At the bottom you have devs who get to be creative but not eat. At the top you get devs who get to eat but not be creative. And there is no middle.

Couldn’t we take a cue from music?

Some external organization should exist that provides credit validation. Today, practices like “oh, she left early, so we’ll just list her in Special Thanks” and “he was Lead, but only for the first half, so we’ll list him under Additional Programming” are not just rampant but culturally accepted practices. Fellow devs will argue that staying to finish a title is the most important thing, which is ludicrous.

Just run some thought experiments; if one person made a whole game for a year, except for the last five minutes, whereupon someone else took over, would you say that they should get credited as “additional”? OK, what if it’s a week? A month? What if they were only there for the first month, which means “all” they did was “just” the game design, architecture, core engine, and art direction? At what point does their contribution become ancillary?

This organization then can maintain the accurate, comprehensive database of all game credits. This will be incredibly useful for other purposes (game resumes are routinely falsified, for example). Further, it can do things like recognize ports and sequels and the like, so that say, Dona Bailey still gets credited on every derivative of Centipede. But our main purpose is this:

All game outlets — App Stores, social networks, what is today the plumbing of our lives — contribute into this org’s bank account, right off the top, out of their 30% cuts. Facebook alone made over a billion dollars in game revenue every quarter last year. Add in Google, Sony, Microsoft, Apple… they really don’t need to skim much off the top to put into this org’s coffers.

Why is it that these folks do it? Because they are also in the position to know what gets played.

And then this credits organization, acting much like a Performing Rights Organization, distributes almost all of that money back to everyone in their database.It’s effectively royalties for every play. Dona Bailey would get a check for people who play some Centipede derivative today.

Oh, and you don’t distribute this evenly. Not fairly, no: unfairly. Tilted so that those who earned the least get a disproportionate payment. After all, if you got lucky in the popularity lottery, you are already earning your capitalistic reward right now. No, this is more for when you are old and gray and haven’t been at that company for ten years, but your game is still making them money.

Why this construct? Because game creators

work for hire

don’t have moral rights in the US

don’t have the sort of IP protection that other media do

Games are the worst protected creative job there is. And given the libertarian politics that are common currency in the industry, they are also the creative group least likely to organize.

How feasible is the above? I don’t know. But I do know that if every developer who put a game up on the App Store knew that they weren’t just going to lose their time and money on it or get screwed over by faceless moneygrubbing gladhanders, we’d see more diversity, more creativity, and plain old more apps.

And if that happened, the ecosystems could a) be a little less worried about solving a probably unsolvable discovery problem b) trumpet ever growing numbers c) likely grow their audiences as diverse creators lead to diverse customers d) hedge the blockbuster problem that is stalking them and will someday hunt them down and kill them.

Ah, I’m probably nuts. I’m sure my suggestion is buggy as hell. But it’s the best I’ve got at the moment.

———————–

As you might guess, Greg Costikyan and I had some conversations during GDC.

May 6, 2014

Is this the future?

Premise: Goods made of bits offer tremendous advantages to providers of said goods.

Therefore, any good that can be described in terms of bits will be.

Therefore, any good that cannot be described in terms of bits that can cheaply phone home will, in the name of better service, causing it to effectively be bits even if it has a physical manifestation.

Therefore, any good that can be described and experienced in terms of bits will cease to be owned and instead be a service.

Therefore, there will be ongoing service costs to all physical goods.

Therefore, because of economics, anything that is a service will eventually get the service turned off.

Therefore, the more we move to bits, the more we have the dead media problem for physical goods.

Observation: Anything with a service that is turned off will get hackers reverse-engineering a fake server to try to keep it functional. That said, I think in most cases platforms die. Hopefuly, a lot of stuff can function with a fake loopback of some sort.

So how long until the Doctrine of First Sale is obsolete entirely? Just wondering.

May 2, 2014

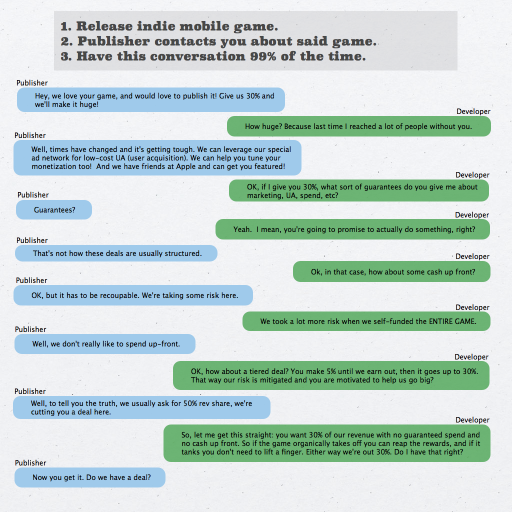

2048: Game Design Theory Edition

I have to post this here for posterity even though I already tweeted it yesterday. Anyone better at 2048 than I who can post the full list of everyone in it? I’ll update the post with the details.

I have to post this here for posterity even though I already tweeted it yesterday. Anyone better at 2048 than I who can post the full list of everyone in it? I’ll update the post with the details.  See below!

See below!

2048: Game Design Theory Edition. Made by Brian Upton.

I can’t get higher than Eric Zimmerman… my daughter saw Frank Lantz though.

Edit: the full list, as provided by commenters:

Chris Crawford

Greg Costikyan

Jesse Schell

Raph Koster

Ernest Adams

Marie-Laure Ryan

Jesper Juul

Eric Zimmerman

Frank Lantz

Ian Bogost

Brenda Romero

April 29, 2014

GDC Next Call for Papers

It’s that time again — GDC Next, the inheritor of the GDC Austin slot, is requesting submissions for talks. The high-level theme this year is, more or less, “after the game idea, what’s next?” We all know that the idea is in many ways the easiest part, and in this climate of maturing markets, knowing what else needs to be done to have a success is mattering more and more for people trying to make a living at games.

It’s that time again — GDC Next, the inheritor of the GDC Austin slot, is requesting submissions for talks. The high-level theme this year is, more or less, “after the game idea, what’s next?” We all know that the idea is in many ways the easiest part, and in this climate of maturing markets, knowing what else needs to be done to have a success is mattering more and more for people trying to make a living at games.

The tracks, and the stuff that we the advisory board want to get submissions on:

Community: including Live community, how and when to use social media, e-sporty stuff, games-as-experience, and everything else that touches on.

Discoverability: Early Access! YouTube! Twitch! How to get seen on the App Store! This section of topics has gotten incredibly important in the last few years, and there are a lot of things that successful indies are pulling off that are worth looking at.

Biz and marketing: Business 101 for game creators! How to tell a good offer from a bad one. How to manage growth. Crowdfunding postmortems. Is there an international market for your game?

Production: Cross-platform — obviously, but how? What are the tradeoffs of the various x-platform engines? And maybe even more importantly, which platforms and when in your game’s lifecycle? How to do test marketing! How to build an IP that a player remembers.

Design: The usual goodness. GDC Austin, and then Next, have historically had sky-high ratings for design talks, some of the best of any of the GDC’s. So game mechanics, stickiness, revenue, smartphone and tablet, all that.

So head on over to the site to get the full details and submit!

April 13, 2014

On SiriusXM tomorrow!

I’ll be speaking on SiriusXM Business radio on The Digital Show Monday at 2pm Pacific/5pm Eastern, with Kartik Hosanagar of Wharton. It’s on channel 111, and the topic will be virtual reality.

This is of course occasioned in part by my post on the sale of Oculus to Facebook, but I hope we spend time talking about the broader context: how VR is one of the things that a beleaguered core gamer audience is looking to as a great saving hope, and how VR has the potential to link into long-dormant Metaverse dreams, and more. And of course, whether VR is really where it’s going to be at, or whether AR is really the hotter space… though really, I am of the opinion that they are more or less the same thing… about which more on the show.

March 25, 2014

Musings on the Oculus sale

Rendering was never the point.

Rendering was never the point.

Oh, it’s hard. But it’s rapidly becoming commodity hardware. That was in fact the basic premise of the Oculus Rift: that the mass market commodity solution for a very old dream was finally approaching a price point where it made sense. The patents were expiring; the panels were cheap and getting better by the month. The rest was plumbing. Hard plumbing, the sort that calls for a Carmack, maybe, but plumbing.

Rendering is the dream of a game industry desperately searching for a new immersion, another step in the ongoing escalation of immersion that has served as the economic engine of ongoing hardware replacement, the false god of “games getting better.” It was an out: the plucky indie that bucked the big consoles but still gave us the AAA. It was supposed to enable “art.”

But rendering was never the point.

It’s time to wake up to the fact that you’re just another avatar in someone else’s MMO.

Look, there are a few big visions for the future of computing doing battle.

There’s a wearable camp, full of glasses and watches. It’s still nascent, but its doom is already waiting in the wings; biocomputing of various sorts (first contacts, then implants, nano, who knows) will unquestionably win out over time, just because glasses and watches are what tech has been removing from us, not getting us to put back on. Google has its bets down here.

There’s a beacon-y camp, one where mesh networks and constant broadcasts label and dissect everything around us, blaring ads and enticing us with sales coupons as we walk through malls. In this world, everything is annotated and shouting at a digital level, passing messages back and forth. It’s an ubicomp environment where everything is “smart.” Apple has its bets down here.

These two things are going to get married. One is the mouth, the other the ears. One is the poke, the other the skin. And then we’re in a cyberpunk dream of ads that float next to us as we walk, getting between us and the other people, our every movement mined for Big Data.

In this world, what is Oculus? What is something as simple as a mere social network? After all, a social network is just ubicomp on people; Facebook on a watch or a pair of glasses is just another way to say that we’ll have our own set of semantic tags and labels stuck on our flesh, with those with the eyes to see. Worse, it’s one that relies on what we say, which is very different from what we do. It’s one that relies on supposed friend networks that are self-reported, when soon enough biometric data will report back up who we actually care about, how our pulse quickens when in the presence of the right person.

I have a deep respect for the technical scale that FB operates at. The cyberspace we want for VR will be at this scale.

— John Carmack (@ID_AA_Carmack) March 26, 2014

The virtue of Oculus lies in presence. A startling, unusual sort of presence. Immersion is nice, but presence is something else again. Presence is what makes Facebook feel like a conversation. Presence is what makes you hang out on World of Warcraft. Presence is what makes offices persist in the face of more than enough capability for remote work. Presence is why a video series can out-draw a text-based MOOC and presence is why live concerts can make more money than album sales.

Facebook is laying its bet on people, instead of smart objects. It’s banking on the idea that doing things with one another online — the thing that has fueled it all this time — is going to keep being important. This is a play to own walking through Machu Picchu without leaving home, a play to own every classroom and every museum. This is a play to own what you do with other people.

Oh, there will be room for games. But Oculus, in the end, serves Facebook by becoming the interface to other people online. I’d feel better about this if Facebook understood people, institutionally. I’m never quite sure if they do.

Long ago, at the Metaverse Roadmapping sessions, we discussed the ways in which virtuality could be used:

Augmented reality

Lifelogging

Virtual worlds

Mirror worlds

#2 is all Glass is currently useful for; a glorified video camera, until the augmented aspect kicks in. The addition of indoor mapping, beacons, Bluetooth LE, mesh networks, and suddenly the first two leap to life. Once it’s here, we’ll forget what life was like without it, swimming in a sea of data.

Facebook is placing its new bet on the bottom half. It already logs lives, in a way. It aspires to be the semantic tags on every abstract entity — that’s what Open Graph was about — but a lot of folks are fighting over that pie, not least of which is Google. What Oculus opens is the bottom two.

A lot of the praxis around virtual worlds — and indeed, games in general — has been co-opted by social media… But it doesn’t mean virtual worlds are over. They are metamorphosing, and like a caterpillar, on the path to mass market acceptance, they are shedding the excess legs and creepy worm-like looks in favor of something that doesn’t much resemble what it sprang from, but which a lot more people will like. And which will be a bit harder to pin down.

In that piece, I said the issues with virtual worlds, the reasons why they were fading, were because what virtual worlds offered was mostly just placeness, at a time when “good enough” placeness was available everywhere. But immersive VR raises the stakes on placeness.

Facebook’s purchase of Oculus is the first crack in the chrysalis of a new vision of a cyberspace, a Metaverse. It’s one that the Oculus guys have always shared. It wasn’t ever about the rendering for them either. Games were always a stepping stone. It was about placeness, and Facebook is providing the populace.

Is it enough to win out? I don’t know. The real world is mighty compelling. The sorts of dreams Oculus enables are the same damn dreams we’ve always had for virtual worlds:

attend a virtual concert

learn in a virtual classroom

talk to a virtual meeting

sleep with a virtual partner

slay a virtual dragon

build a virtual cathedral

Oh, it can be the best damn version of this ever. But to me the trends say that building the cathedral out of nano-based smart dust may end up being a bit more compelling. It certainly provides a more direct path to the money, and let’s not kid ourselves, anyone who spends $2 billion cares about the money.

Either way, no matter who wins out, it was never about the rendering. All four of these visions have one thing in common: the servers.

It’s about who owns the servers.

The servers that store your metrics. The servers that shout the ads. The servers that transmit your chat. The servers that geofence your every movement.

It’s time to wake up to the fact that you’re just another avatar in someone else’s MMO. Worse. From where they stand, all-powerful Big Data analysts that they are, you look an awful lot like a bot.

The real race isn’t over the client — the glasses, watches, phones, or goggles. It’s over the servers. It’s over the operating system. The one that understands countless layers of semantic tags upon every object on earth, the one that knows who to show you in Machu Picchu, the one that lets you turn whole visualizations of reality on and off.

Hopefully, the one that isn’t owned by anyone. (I have a spec I started. But nobody wants it. Money, remember?)

Pshhht, rendering? We’ll get new client hardware, new client software. Big whoop. I’m a lot more worried about whose EULA is going to govern my life.

GDC: Building game retention tips

Aside from the ten minute talk at Critical Proximity that I posted yesterday, I spoke for an additional six minutes at GDC2014 (yes, that’s unusually low commitment for me!). It was a microtalk on retention tips for free to play games in the “build and invest” genre — stuff like farming games, city games, all those isometric games where you plonk down little objects. You can find the archived presentation here.

Quests work against self-expression. They force you to build what the developers want, not what you want.

Most of the panelists focused on the “modern” use of the term “retention” — which is to say, they focused on how to get people to come back for the second day, or for a week. The phrase “daily login bonus” was a common reference. But I knew that would be the case, and so took the opportunity to continue my hapless crusade to get social-style games to greater heights of community and user involvement.

So I presented on the topic of the real ways to get greater retention, like on the order of months. After all, we forget that SimCity, The Sims, Minecraft, and Dwarf Fortress are also “build and invest” games, and have much to team those on the more casual side of the spectrum. (Anyone else remember when SimCity was the casual side of the spectrum??) For anyone who found yesterday’s talk academic and vague, this one is very straightforwardly concrete.

Some of the questions after the presentation were also quite good. One was on the issue of borrowing techniques from one genre into another, and the answer given by Teut Weidemann was “steal from MMORPGs,” which I think every panelist agreed with. I also got someone asking me whether we would see cryptocurrencies hooked directly into games, with games serving as miners and so on. My answer was, not until all regulatory fears are removed, at least as far as larger publishers are concerned.

March 24, 2014

A New Formalism: Critical Proximity talk

The debates about “what is a game” happened between multiple overlapping circles that have very little to do with one another… “Games” is never going to fall into one bucket or critical lens… We enrich ourselves and our mutual understanding not by claiming pre-eminence of one circle, but by learning to move between them.

On the Sunday before GDC, I attended and spoke at Critical Proximity, a games criticism conference. It was quite excellent. I am left with many thoughts, which will have to go into a separate post on the subject. In the meantime, there are write-ups available in several places:

Polygon

The Escapist

The Man of Many Frowns

The Conversation

Video Games of the Oppressed

Media &c.

As regular readers know, I have been involved in a lot of discussions about “formalism” in games over the last few years. This talk was an attempt to reset the conversation with insights into “formalism in the real world” as Brendan Keogh put it on Twitter, a look into the ways in which looking at the formal structure of games is able to help out and illuminate all sorts of games criticism. Including “softer” or more humanistic approaches, such as historiography, study of play, and cultural studies approaches.To that end, I deployed a set of analogies from other media: fine art, and poetry, and music, to help draw connections between the ways formal approaches and even notation are used in these other fields, and how we might use them in ours.

My talk is below the fold (hover over the slides for the notes text), and for the full transcript plus a link to the video, go here.

There were many other talks I highly recommend… the entire Twitch stream is available (see that same link) and lasts 8 hours!

#metaslider_15788_filmstrip.flexslider .slides li {margin-right: 5px;}

#metaslider_container_15788 .flexslider,

#metaslider_container_15788 .flexslider img {

border-radius: 1px;

-webkit-border-radius: 1px;

-moz-border-radius: 1px;

}

#metaslider_container_15788 .flexslider .caption-wrap {

opacity: 1;

margin: 0px 0px;

color: rgba(255,255,255,1);

background: rgba(0,0,0,0.7);

width: 100%;

top: auto;

right: auto;

bottom: 0;

left: 0;

clear: none;

position: absolute;

}

#metaslider_container_15788 .flexslider .flex-prev,

#metaslider_container_15788 .flexslider .flex-next {

height: 25px;

width: 25px;

margin-top: -12.5px;

background: url(http://www.raphkoster.com/wp-content/...

}

#metaslider_container_15788 .flexslider .flex-direction-nav .flex-prev {

background-position: 0 -226px;

}

#metaslider_container_15788 .flexslider .flex-direction-nav .flex-next {

background-position: 100% -226px;

}

#metaslider_container_15788 .flexslider:hover .flex-direction-nav .flex-prev {

left: 5px;

opacity: 0.7 !important;

}

#metaslider_container_15788 .flexslider:hover .flex-direction-nav .flex-next {

right: 5px;

opacity: 0.7 !important;

}

#metaslider_container_15788 {

margin-bottom: 32px !important;

}

I’m here to represent the formalists!

I’m here to represent the formalists! New formalism is a term from poetry. I like poetry. I reference it in talks like these. I write poetry, sometimes. I have a poetry sheepskin. Poetry is nice, and kind of irrelevant. It doesn’t make a good reference point for people usually because nobody, not even most poets, reads poetry, unless they are forced to.

New formalism is a term from poetry. I like poetry. I reference it in talks like these. I write poetry, sometimes. I have a poetry sheepskin. Poetry is nice, and kind of irrelevant. It doesn’t make a good reference point for people usually because nobody, not even most poets, reads poetry, unless they are forced to.Back when I was in college, we railed against what we called “me poetry.” It was a confessional moment in culture, you see, and for that matter, I think every poet coming out of high school is probably writing confessional poetry, it’s almost like a law of nature… just like it is a sort of a law of nature that if you are a student, you have to rail mightily against whatever the prevailing winds are. That’s part of your role, to be the rebel.

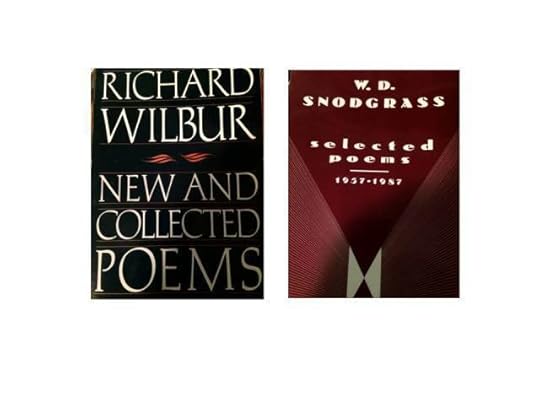

New Formalism, then, was a rebellion. It was already an old rebellion when we came along. Poetry movements happen in very slow motion; this was people like Dana Gioia and Dick Allen and Snodgrass rebelling against

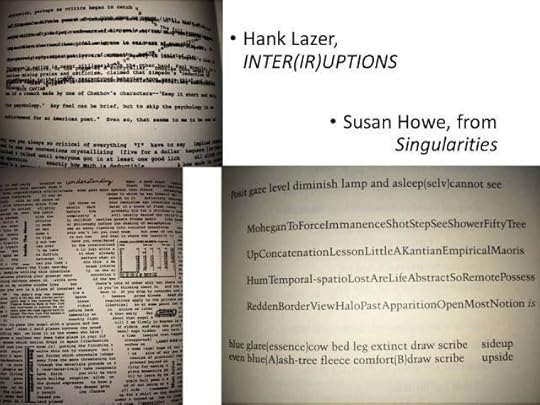

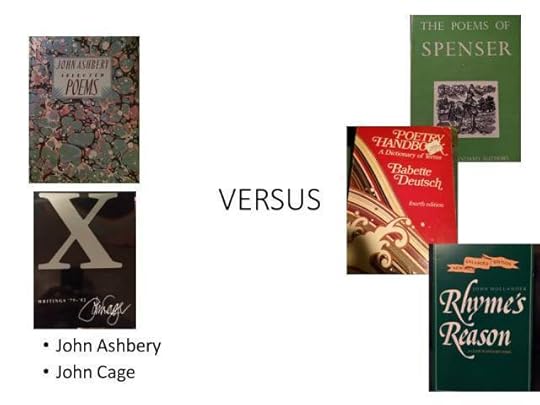

New Formalism, then, was a rebellion. It was already an old rebellion when we came along. Poetry movements happen in very slow motion; this was people like Dana Gioia and Dick Allen and Snodgrass rebelling against language poetry and concrete poetry,

language poetry and concrete poetry, Ashbery or even Whitman. So we are talking a fifty year old rebellion against a hundred year old trend, and the way it rebelled was by reaching back even further, to formal verse techniques from five hundred years prior.

Ashbery or even Whitman. So we are talking a fifty year old rebellion against a hundred year old trend, and the way it rebelled was by reaching back even further, to formal verse techniques from five hundred years prior. We can call that a kind of conservatism, I suppose. Gioia kicked off the naming of the movement by complaining not just about confessionalism but about “unmusicality” in the language used. I mean, talk about missing the point of language poetry and concrete poetry, to complain about its lack of musicality, instead of celebrating its physicality, right?

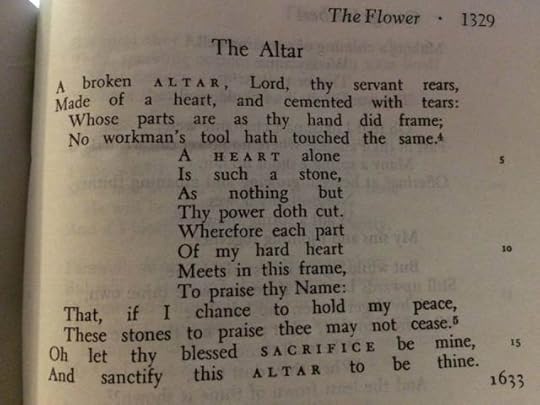

We can call that a kind of conservatism, I suppose. Gioia kicked off the naming of the movement by complaining not just about confessionalism but about “unmusicality” in the language used. I mean, talk about missing the point of language poetry and concrete poetry, to complain about its lack of musicality, instead of celebrating its physicality, right? But the picture isn’t that simple… For one, George Herbert showed us centuries ago that physicality and musicality can coexist just fine. It’s not like these are even on an axis or anything.

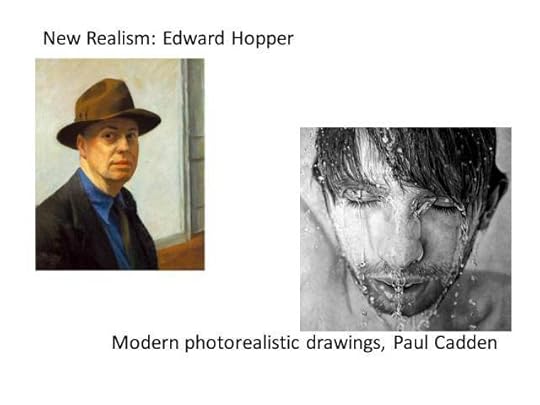

But the picture isn’t that simple… For one, George Herbert showed us centuries ago that physicality and musicality can coexist just fine. It’s not like these are even on an axis or anything. For another, we can call harking back to the extreme past radical, similar to how New Realism in painting is upending abstraction but also the forms of representation that have grown common.

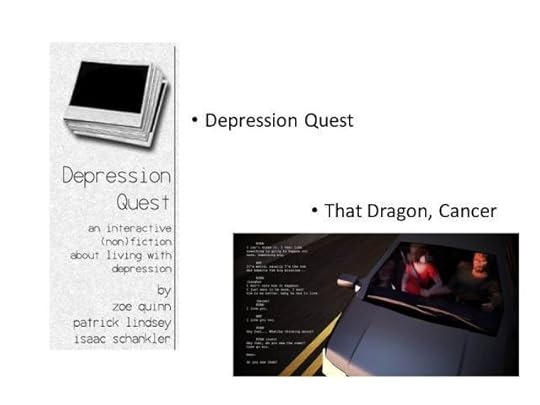

For another, we can call harking back to the extreme past radical, similar to how New Realism in painting is upending abstraction but also the forms of representation that have grown common. A lot of art games and indie games feel analogous to language poetry,

A lot of art games and indie games feel analogous to language poetry, Or to confessionalism, and frankly, we could probably link a curmudgeonly statement like “unmusicality” to curmudgeonly statements like “not a game.”

Or to confessionalism, and frankly, we could probably link a curmudgeonly statement like “unmusicality” to curmudgeonly statements like “not a game.” Another lens, though, is that New Formalism was actually a populist movement, seeking to reclaim an audience for poetry using the strengths that it had once had – much like casual games are populist in very large part because they eschew heavy narrative and presentation elements and focus strongly on a systemic core. And in that sense, it wasn’t that far out of tune with the culture as a whole. It suffered, probably, from being too much a movement of older white men,

Another lens, though, is that New Formalism was actually a populist movement, seeking to reclaim an audience for poetry using the strengths that it had once had – much like casual games are populist in very large part because they eschew heavy narrative and presentation elements and focus strongly on a systemic core. And in that sense, it wasn’t that far out of tune with the culture as a whole. It suffered, probably, from being too much a movement of older white men, Given that the same impulses did actually lead to a “classical” poetic revival, just in the form of a small singer-songwriter resurgence,

Given that the same impulses did actually lead to a “classical” poetic revival, just in the form of a small singer-songwriter resurgence, Slam and performance poetry,

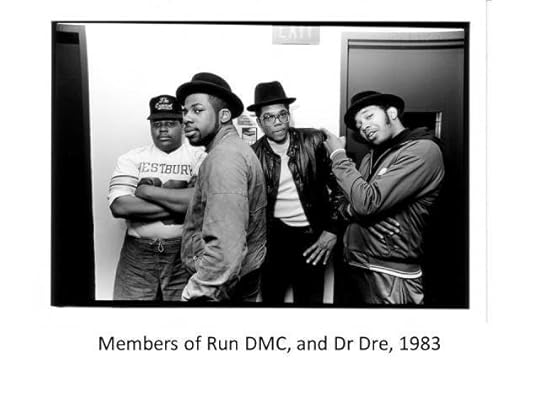

Slam and performance poetry, And hip hop. All of which have more in common with New Formalism than they do with the avant garde of poetry at that time, or even the widely accepted contemporary poet canon of that period.

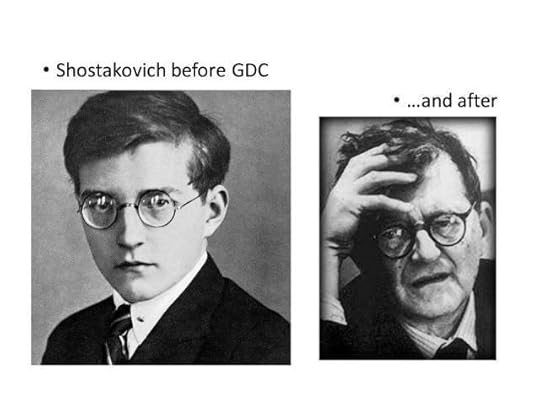

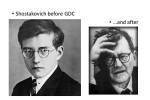

And hip hop. All of which have more in common with New Formalism than they do with the avant garde of poetry at that time, or even the widely accepted contemporary poet canon of that period. Formalism in games was a label imposed from outside the supposed formalists. In music, it’s applied to the avant garde composers like Shostakovich. Which raises two important points:

Formalism in games was a label imposed from outside the supposed formalists. In music, it’s applied to the avant garde composers like Shostakovich. Which raises two important points:1) That usually the avant-garde is associated with the formalist mode of thinking, so it is sort of weird that in games it’s associated with the reverse

2) That formal terms are always bounded, always occur within a deep context of practice and culture. What is formal to one is very informal to another, and the use of a given word within the context of Stalinist Russia can have deeply different implications when it is heard – not even used, just heard – by someone in another field, time, or place.

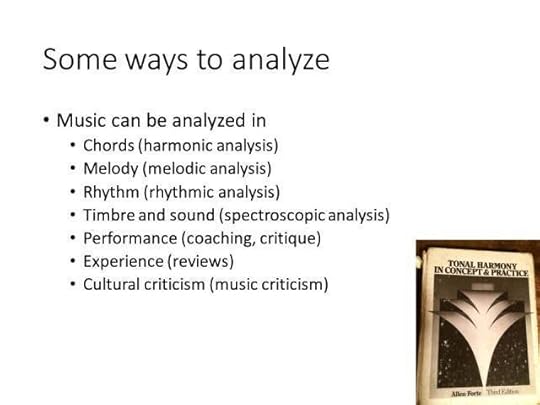

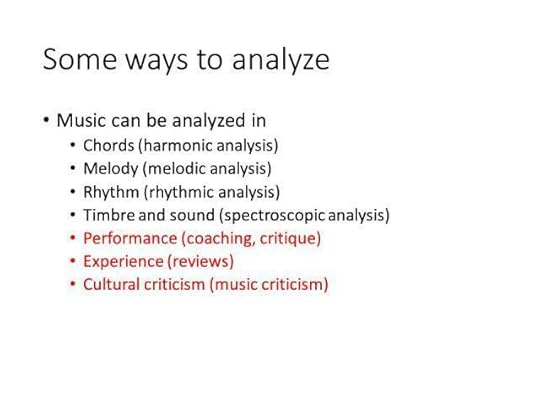

If we leave the poetry aside for a moment and use music as an analogy, these are all ways of looking at music, of doing music criticism.

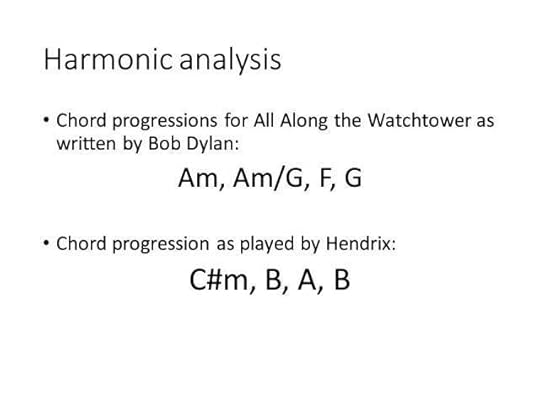

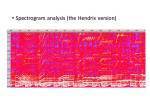

If we leave the poetry aside for a moment and use music as an analogy, these are all ways of looking at music, of doing music criticism. This is “All Along the Watchtower” – the Dylan original, versus the Hendrix take, wherein we can see via the chords that Hendrix actually turned a passing note into a full chord. Harmonic analysis shows us how these are actually pretty different.

This is “All Along the Watchtower” – the Dylan original, versus the Hendrix take, wherein we can see via the chords that Hendrix actually turned a passing note into a full chord. Harmonic analysis shows us how these are actually pretty different. But of course melodic analysis says they are the same. After all, this here is also “All Along the Watchtower.”

But of course melodic analysis says they are the same. After all, this here is also “All Along the Watchtower.” And then you have stuff like the Michael Hedges cover. Same melody, but radically different rhythmic pattern to it.

And then you have stuff like the Michael Hedges cover. Same melody, but radically different rhythmic pattern to it. A producer might well be much more interested in a spectrogram analysis to see whether the transients are punchy enough.

A producer might well be much more interested in a spectrogram analysis to see whether the transients are punchy enough. And then there’s a critique of someone on American Idol butchering the song, or a review of a new version, or the stuff that I think most game criticism is currently oriented around, which is criticism that connects back out to the larger culture. For example, it might be talking about the way in which the Indigo Girls reinvented the track with a sizable break in the middle, transforming it pretty radically and removing it from its extant context.

And then there’s a critique of someone on American Idol butchering the song, or a review of a new version, or the stuff that I think most game criticism is currently oriented around, which is criticism that connects back out to the larger culture. For example, it might be talking about the way in which the Indigo Girls reinvented the track with a sizable break in the middle, transforming it pretty radically and removing it from its extant context. Game grammar, which is the sort of formalism associated with all these folks, pretty much all fits down at the lower end of this. It’s about the harmony and melody of games, which are the most mechanical pieces and also the hardest to see.

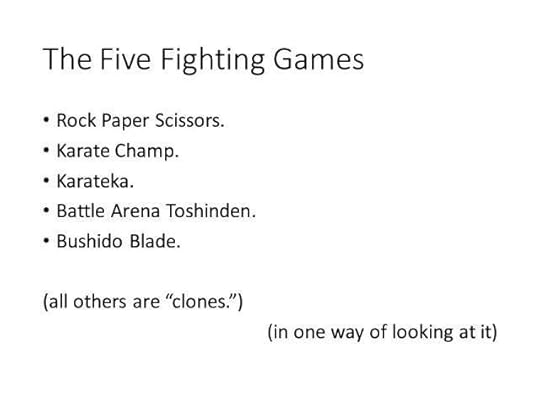

Game grammar, which is the sort of formalism associated with all these folks, pretty much all fits down at the lower end of this. It’s about the harmony and melody of games, which are the most mechanical pieces and also the hardest to see. Mechanical bits tend to be invariant across huge swaths of games. By this lens, most of Saints Row IV is pretty much exactly the same as GTA IV, there have only been five fighting games ever, and Gone Home is a game about turning over cards in a fairly fixed order to read what is on the other side. What most criticism calls “a genre,” this most rigid of lenses might actually call “all the same game” or “variants.”

Mechanical bits tend to be invariant across huge swaths of games. By this lens, most of Saints Row IV is pretty much exactly the same as GTA IV, there have only been five fighting games ever, and Gone Home is a game about turning over cards in a fairly fixed order to read what is on the other side. What most criticism calls “a genre,” this most rigid of lenses might actually call “all the same game” or “variants.” But that’s OK, because as has been said by everyone from Woody Guthrie on, all you need is three chords and the truth to get a message across. Many great pieces of music have been written with a I-IV-V progression, after all. And knowing that a song can be placed in “the blues” actually imparts a whole large dimension to criticism of it. It fits it into a cultural framework, certainly.

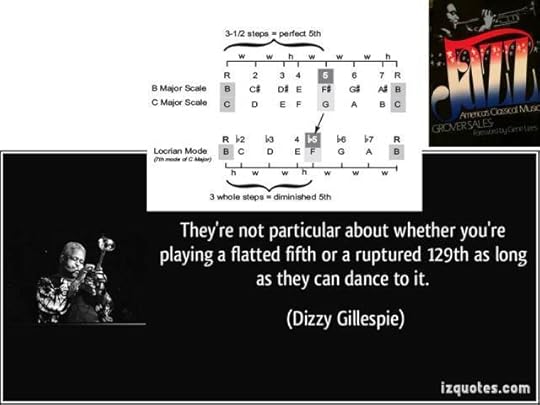

But that’s OK, because as has been said by everyone from Woody Guthrie on, all you need is three chords and the truth to get a message across. Many great pieces of music have been written with a I-IV-V progression, after all. And knowing that a song can be placed in “the blues” actually imparts a whole large dimension to criticism of it. It fits it into a cultural framework, certainly. The first lens that I think this sort of incredibly rigid and dry way of looking at things helps is in any form of historiography efforts. You cannot trace the development of jazz without following one particular note, the flatted fifth, in its winding journey from African scales to bent notes and thence to reclaiming the tritone or “devil’s interval” from its disdained position in the Western music orthodoxy.

The first lens that I think this sort of incredibly rigid and dry way of looking at things helps is in any form of historiography efforts. You cannot trace the development of jazz without following one particular note, the flatted fifth, in its winding journey from African scales to bent notes and thence to reclaiming the tritone or “devil’s interval” from its disdained position in the Western music orthodoxy.That journey is cultural, political, AND technical, and cannot be understood outside of the intersection of all those lenses.

Another way where formal-style bright lines help is in creating negative space.

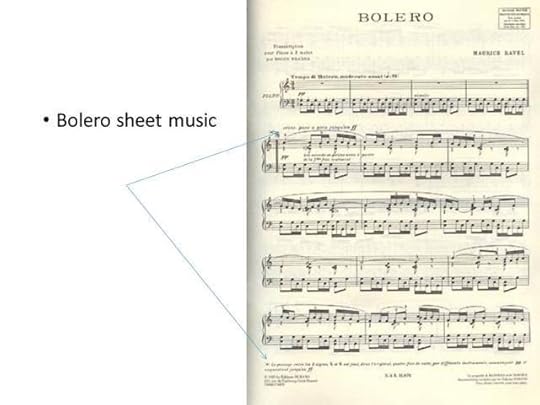

Another way where formal-style bright lines help is in creating negative space. If you see here on this sheet music, there are dynamics notated, performance annotations. This is actually somewhat similar to the notion of dynamics within games as well. In fact, this piece cannot be discussed without attention to its dynamics, because it is literally the same melody and harmony over and over.

If you see here on this sheet music, there are dynamics notated, performance annotations. This is actually somewhat similar to the notion of dynamics within games as well. In fact, this piece cannot be discussed without attention to its dynamics, because it is literally the same melody and harmony over and over. There’s vast scope in dynamics – Using a formalist lens that regards the harmony and melody as distinct from the performance and the timbres, you can actually peel away the bones these have in common in order to better look at the parts that are different.

There’s vast scope in dynamics – Using a formalist lens that regards the harmony and melody as distinct from the performance and the timbres, you can actually peel away the bones these have in common in order to better look at the parts that are different. The biggest place where I think formalism can assist with this in games is in examining the rhetorics of games. There has been movement towards a unique rhetorics of games via stuff like Ian Bogost’s work.

The biggest place where I think formalism can assist with this in games is in examining the rhetorics of games. There has been movement towards a unique rhetorics of games via stuff like Ian Bogost’s work. That’s actually fairly formalist. But if we start to regard the story layer that formalism intentionally blows off as being a performative layer, I suggest that instead, we could leverage quite a lot of traditional rhetorics. If we can describe a system as using anaphora or metonymy, I think we go a long way towards better understanding not only of those systems and those game stories,

That’s actually fairly formalist. But if we start to regard the story layer that formalism intentionally blows off as being a performative layer, I suggest that instead, we could leverage quite a lot of traditional rhetorics. If we can describe a system as using anaphora or metonymy, I think we go a long way towards better understanding not only of those systems and those game stories, but also towards understanding how systems themselves function in those rhetorical roles in our everyday lives. And the thing is that this lingo exists and can be leveraged. It is just the formalism of another discipline, one which humanities-centric critics are maybe so steeped in that they do not see it as a formalism.

but also towards understanding how systems themselves function in those rhetorical roles in our everyday lives. And the thing is that this lingo exists and can be leveraged. It is just the formalism of another discipline, one which humanities-centric critics are maybe so steeped in that they do not see it as a formalism. The other big lens that I think formalism has the potential to illuminate is the notion of play. We still say we “play” music.

The other big lens that I think formalism has the potential to illuminate is the notion of play. We still say we “play” music.Lately, games formalism is starting to say that ludic structures are everywhere; that there are chord progressions and a beat you can dance to everywhere in life. That means we can apply the critical language of game studies, such as it is, to elements well outside the label of games.

Elections. Wall Street, lots of vast systems in the world, are interpretable as ludic structures, as games we play with one another, as games we play without consent, as games we are tokens in. And critics could go beyond the shallow and facile & actually offer real critique of those systems in a way that opens up both means of social change and realms for art to explore.

Elections. Wall Street, lots of vast systems in the world, are interpretable as ludic structures, as games we play with one another, as games we play without consent, as games we are tokens in. And critics could go beyond the shallow and facile & actually offer real critique of those systems in a way that opens up both means of social change and realms for art to explore. In the end, it takes a formal lens to really discuss the ideas that Twine is also avant-garde literature, and the social issues affecting the 99% have a lot more in common with behavioral structures in World of Warcraft guilds, or the tournament structure in League of Legends. This blue shells critique could not have happened without a deep understanding of formal game elements.

In the end, it takes a formal lens to really discuss the ideas that Twine is also avant-garde literature, and the social issues affecting the 99% have a lot more in common with behavioral structures in World of Warcraft guilds, or the tournament structure in League of Legends. This blue shells critique could not have happened without a deep understanding of formal game elements. The debates about “what is a game” happened between multiple overlapping circles that have very little to do with one another: who sits on awards panels, and what is taught in universities, and whether feedback is narrative, and whether all kinds of people are able to make games in the culture as it now sits… the debate is completely different depending on where you were standing. “Games” is never going to fall into one bucket or critical lens; but we can build bridges and connections between buckets using these analyses, and in the end that is a far more intersectional approach, because it recognizes identity as well as commonalities. We enrich ourselves and our mutual understanding not by claiming pre-eminence of one circle, but by learning to move between them.

The debates about “what is a game” happened between multiple overlapping circles that have very little to do with one another: who sits on awards panels, and what is taught in universities, and whether feedback is narrative, and whether all kinds of people are able to make games in the culture as it now sits… the debate is completely different depending on where you were standing. “Games” is never going to fall into one bucket or critical lens; but we can build bridges and connections between buckets using these analyses, and in the end that is a far more intersectional approach, because it recognizes identity as well as commonalities. We enrich ourselves and our mutual understanding not by claiming pre-eminence of one circle, but by learning to move between them.

",

slideshow:false,

sync:'#metaslider_15788_filmstrip',

animationLoop:false,

useCSS:false

});

};

var timer_metaslider_15788 = function() {

var slider = !window.jQuery ? window.setTimeout(timer_metaslider_15788, 100) : !jQuery.isReady ? window.setTimeout(timer_metaslider_15788, 100) : metaslider_15788(window.jQuery);

};

timer_metaslider_15788();