Raph Koster's Blog, page 13

September 7, 2014

The Sunday Poem: London Squall

London squall, Islington gusts,

London squall, Islington gusts,

Wash the Barbican clean.

Tidy households in tiny flats

Open windows, let out cats

As raindrops stop and shatter

And rental bikes go clattering

Down Clerkenwell streets.

Puddles, unavoidable mess,

Are temporary consequence.

Each lost leaf in King’s Square

Is labeled where it fell.

London squall and Islington gusts

May discomfit, yes. But we will not

Permit them to disrupt.

- Outside a café, London, Aug 2014

September 2, 2014

What makes a game last a generation?

Problems that aren’t actually solvable. Instead, players can only approach optimality. This means there’s always another hill to climb in terms of increasing skill, so people keep devoting the time.

Problems that aren’t actually solvable. Instead, players can only approach optimality. This means there’s always another hill to climb in terms of increasing skill, so people keep devoting the time.

These tend to be problems that fall into high complexity classes. In general, NP-HARD problems that we solve using heuristics make for long-lasting games. Mind you, these problems need to be intrinsic to the core game loop. I refer you to my presentation on that here: Games Are Math slides.

No end in sight for problem variations. New problems using the same ruleset is also a way to give hills to climb. (Yeah, this means that “authored” games with fixed levels are almost certainly not going to endure in quite the same way. A narrative game is very unlikely to last a generation.)

The typical ways of providing apparently endless content are:

a decently large permutation space. We have an enormous ability to prune possibility space in our mental models. Tic-Tac-Toe is small enough we solve it pretty readily. In contrast, there are a lot of possible games of go.

a human opponent. Humans add in a whole new set of problems that are also inherently hard, problems of psychology and status.

procedurality in problem set generation. Every game of Tetris is different. The weather adds random elements to every sporting event. And so on.

Independence from representation. Games that endure a generation or more are ones that are susceptible to the folk process, that embrace the idea of being co-opted by their players.

So: Games that endure are ones that survive reskinning, graphic design changes, etc., in order to ensure viability over cultural shifts. Think chess sets; or the way in which Monopoly stays relevant in part because of silly Monopoly reskins.

It also, critically, includes ease of replication. Battleship endures in part because it can be played on a napkin. Games with finicky custom pieces are less likely to survive. Games tied to an input method on a specific technological platform, way less likely… already we see Wii games with custom peripherals that are almost unplayable. The more things tying the game to a particular incarnation or instantiation, the less likely it will be to endure.

Sometimes platforms are extremely widespread, like the standard deck of cards, or round balls. If you can build on something like that, which is always pretty available, you can leverage its ubiquity.

Accessibility is deeply related to this. A game that is too complex or demanding to learn will provide too high a barrier for entry. Usually games like that are coupled with heavy dependence on representation or technical platform.

External support, via either ongoing marketing funds or cultural support in some fashion, to prop the game up when it might otherwise fade. For example, Monopoly endures not only because of the ongoing marketing, but also because of the social tradition of family game night. Chess survives in part because being good at chess is a status symbol and cultural marker. Many sports are deeply tied to a given culture’s self-image, rituals, or educational systems. In this sense, games aren’t any different from any other cultural artifact — the more they are woven into life in various ways, the more likely they are to become a custom.

Luck. Games endure in part because of popularity, and popularity is itself heavily driven by luck. Studies have shown that “quality,” apart from being kind of an arbitrary judgement, has a relatively weak influence on overall popularity. Social confirmation is the primary driver of popularity. If a game does not pop up to high popularity early on, it likely won’t stick around. And note, popping to high popularity isn’t itself a guarantee of future endurance (see Where does popularity come from, or the Wisdom of Crowds revisited)

For an alternative view with a lot in common with my answer, you may want to read Dan Cook’s article here: Gamasutra: Daniel Cook’s Blog or check into some of the design work of Frank Lantz.

This post originated on Quora…

September 1, 2014

Open letter to the gaming community

I am a signatory to this letter. I think everyone should be. I think it should be pretty non-controversial, actually.

We believe that everyone, no matter what gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, or religion has the right to play games, criticize games and make games without getting harassed or threatened. It is the diversity of our community that allows games to flourish.

If you see threats of violence or harm in comments on Steam, YouTube, Twitch, Twitter, Facebook or reddit, please take a minute to report them on the respective sites.

If you see hateful, harassing speech, take a public stand against it and make the gaming community a more enjoyable space to be in.

Thank you

August 16, 2014

Random UO anecdote #2

I just stumbled across this old story I told somewhere, and thought I’d share more widely.

I just stumbled across this old story I told somewhere, and thought I’d share more widely.

In Ultima Online, the player was a container — one you couldn’t open, but which held your equipped items, your backpack which was the container you could actually see, etc. Because of the freeform “gump”1 style containment system used in the Ultimas, you could position anything to any location in a container, which meant they were basically treated like maps, with coordinate systems in them.

Then we added mounts.

When you rode a horse, we simply put the horse inside the player, and spawned a pair of pants that looked like your horse, which you then equipped and wore.

When we first did this, however, we forgot to make the horse stop acting like a horse. Pretty soon there was a rash of server crashes because the horse inside the player was wandering around, picking up the stuff it found inside the player, rifling through the player’s backpack and eating things it thought were edible, and eventually, wandering “off the map” because the player’s internal coordinate system was pretty small, and the edges weren’t impassable.

According to UoGuide, “graphical user menu pop-up.” It was the term that was used at Origin back then, long-forgotten now expect maybe among the UO emu community. Basically, any UI window of arbitrary shape floating above the game. In UO, inventory systems did not use slots but free placement on a coordinate system. ↩

August 12, 2014

Wikipedia is a game

The tl;dr version is “go here for the talk.”

The tl;dr version is “go here for the talk.”

This past week I was in London, attending Wikimania 2014. Many thanks to Ed Saperia and the organizers for inviting me to speak, it was a highly illuminating experience.

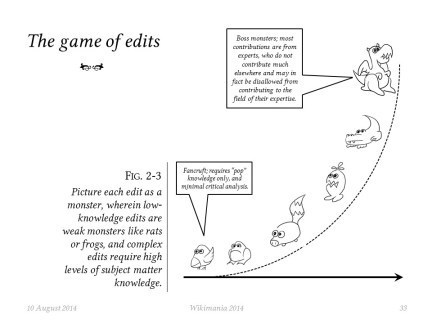

I gave a talk about seeing the Wikipedia experience itself as a series of games: the game of being a reader, the game of editing (or attempting to edit) the content within, and the game of active participation in the community, in terms of working with its policies, its infrastructure, and so on.

Along the way, my intent was to basically toss a few hand grenades in the general vicinity of the foundations of Wikipedia, and in fact of the larger Wikimedia project. This is one of the most idealistic projects in all of human history, and a group of highly intelligent and altruistic people who are fortunately very open to self-examination. So I felt that maybe questioning some of the fundamental assumptions about how they saw themselves and their project was something healthy, and maybe something that would be extra-helpful if done by an outsider.

To make it extra fun, I tried to make the slides look like they were from an old print book.

You can find the slides as a slideshow or as a PDF, and even video of the talk, all here on this new page I have created. I also participated in a panel with a bunch of wonderful folks, on the broader topic of virtual communities. That video is also posted there.

I left the conference thinking a lot about complex systems thanks to lengthy chats with Yaneer Bar-Yam, and toying with the idea of reframing my various definitions of play and games as just “dealing with complexity.” About which more later, I am sure, as it continues to percolate.

August 4, 2014

Wikimania 2014 in London

I am speaking this week at Wikimania 2014 in London. I’m speaking in the “social machines” track, which is about systems wherein the code and the people are inseparable — as in Wikipedia itself, social network systems of all sorts — and of course, multiplayer games. I’ll be doing both a lecture session and participating on a panel.

I am speaking this week at Wikimania 2014 in London. I’m speaking in the “social machines” track, which is about systems wherein the code and the people are inseparable — as in Wikipedia itself, social network systems of all sorts — and of course, multiplayer games. I’ll be doing both a lecture session and participating on a panel.

In the talk, I am going to be very literal, and talk about Wikipedia as a game. It seems to me that Wikipedia as a system is unquestionably what I call a “ludic system,” a construct that lends itself to game-playing. It was not constructed as such, however (my term for intentionally constructed systems like that is “ludic artifact.”) The fact that it was not intentionally designed as such means that we can look at it with a jaundiced designer’s eye, and see ways in which is functions poorly as a game.

Of course, I may touch on some of the controversies we have seen in the MUD community over the years around notability, sourcing, and experts, as they make for good illustrative examples. (See, in order, “Losing MUD history,” “Wikipedia, MUDs, and where the sources are,” and “Saving MUD history.”)

I’m pretty excited to talk about all this, because it’s a chance to use games as a lens through which to analyze a decidedly non-game system (something I advocated for at Critical Proximity). I have hopes it offers a very different lens through which to think of “gamification.” Simply put, how much better could we make many of the world’s systems if we identify ones that are already ludic artfacts, then talk about how to design them better — rather than trying to force game-ness onto systems that are simply not rich enough to bear the weight and therefore collapse back into pointsification?

In any case, if you happen to be in London this week, stop by and say hi!

By the way, I have added a calendar to the sidebar; I have several other speaking engagements this fall. So you can poke around over there to see where else I will be.

July 23, 2014

When is a Clone

Just some relatively incoherent notes here, originally written in an email… this post may serve as useful background as it expresses many of the same thoughts in a more coherent form. This was written in part in response to all the discussion around cloning going on in the game industry these days. As it happens, today I read this Gamasutra blog post:

Everything that can be invented has been invented.

Which prompted me to post this here.

“Game” here used in a strict formal sense, to save me from typing “ludic artifact” over and over again.

Most games can be described as rules (e.g., processes that are largely based on conditionals, limits, and actions) and sets of numeric values (number of an asset type, values for things, etc). You also have a variety of metaphors and presentation elements that are used to convey these: visuals, sounds, etc.

Most games can be described as rules (e.g., processes that are largely based on conditionals, limits, and actions) and sets of numeric values (number of an asset type, values for things, etc). You also have a variety of metaphors and presentation elements that are used to convey these: visuals, sounds, etc.

In general, if we see a game that has all the same rules and all the same scalars, but uses different presentation, we can consider that “a reskin.” It is exactly the same as a Lord of the Rings chess set or the like.

If a game has the same rules but different scalars, we can think of it as the same game simply presenting alternate problem spaces. For example, changing levels is changing scalars. Changing jump distance, etc. This is generally also a “clone” or “reskin.”

Pac-Man

Note, a scalar going to zero, or a new scalar that therefore comes with a new rule (limit, mechanic, input and contingent rule) effectively creates what I would call a “variant.” Many games include variants within their rules, others are sometimes considered new games. Look at Poker.

Variant trees can get pretty complex, and pretty soon we end up referring to a “family” of games.

If it gets large enough, we call it “a genre.” A genre shares a common core set of mathematical problems but the rules around them can be so diverse that any given pairing of two members of the tree will find little commonality. Genres are really best seen through cluster analysis because they can bleed into one another.

So: new unique rule combinations create new games, which by definition create the original “variant” though there is nothing to vary from yet, which makes them the first member of a new family, and potentially the founder of a genre. But usually games are not invented ex nihilo.

You have do have some numeric rules that are almost like “global variables” – one of these is a scalar for “turn time.” Changing this one can very much create a “new game.” The same game construct with turns, phases, or real time will get called “a new game,” because turn time is a rule.

The easiest way to “invent a new game” as opposed to simply cloning something is to take a ludic artifact and change one significant rule.

Miner 2049er

Not all rules are created equal. Some rules are very much peripheral – for example, an in-built exploration system (such as finding secrets) is effectively a braided-in minigame that happens in parallel to the “main game.” This is where atomic analysis is useful. Usually, you can see where minigames exist in parallel to a core game, and it’s usually obvious which is the core and which is the minigame, based on where resources flow.

Sometimes, rule changes like this (as in Poker) feed back into the core structure, and become a scalar instead, creating that sense of family. So adding a wild card is unquestionably a rule change, but these days “number of wild cards” or “face up cards” are actually scalars from 0 to n. Similarly, FPSes have developed variants like this (instagib, for example).

The commonest way to find a major variant is to add a dimension. Move from 1d to 2d to 3d to 4d, or back. This has been the evolution of shooters, of racers, etc. Adding time as a dimension is also a common tactic.

New graph types is a very common way to do it as well. Going from Bejeweled to Hexic introduces a new kind of mathematical relationship and topology, which results in new rules to handle it, which means a new game.

Flip & Flop

So, the recipe for inventing a truly new game:

Identify a new mathematical model. This is often done by finding a new kind of scenario to model: human relationships (The Sims), gardening (Farm Town), etc.

Proffer a dimensional change on an existing ruleset, such as Tetris modifying the classic game of pentominoes by adding time and movement vector. Pac-Man and Miner 2049er and Flip & Flop are almost the same game (traverse every node on the graph). But the rule changes are major.

Explore alternate sorts of graph structures, such as Blokus to Blokus Trigon or Gemblo . Jumpman vs Miner 2049er is a good example here, or indeed any other “gather things” platformer; changing the graph of points that require visiting alters much.

Offer a replacement goal within an extant rule structure, which can force a major variant. A racing game versus a demolition derby sort of racing game is an example here.

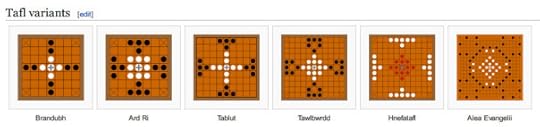

That said, the folk process virtually demands that games be cloned, experimented on, reskinned, and otherwise evolved as machines. Look at the tafl family of games, for example, or Nine Men’s Morris. Arguably a game that does not get cloned can never become a family or genre.

On top of that, there are expressive qualities in the metaphor that afford enormous artistic scope. They don’t fall into the realm of “ludic artifact design” but rather into “experience design” (both subsets of “game design”), but they still advance the overall field. Half-Life is perhaps the quintessential example here.

Anyway, where that leaves us with clones… first off, they’re normal. Second, we as (ludic artifact) designers work in rulesets, and rulesets are conventionally not protected except by patents – so we could protect these constructs, we just usually don’t bother. Third, without a good way to talk about rulesets, we use rules of thumb to point at stuff and say “that’s a clone,” so it’s a great place where formal game analysis methods help our thinking.

July 10, 2014

Interactive Mountain

Everyone is talking about Mountain.

Everyone is talking about Mountain.

Mountain is a game where you see a 3d mountain. It can be turned. You can play some notes on the keyboard. The mountain does things on its own. Trees grow, clouds, etc. It “says” things. Stuff falls from the sky. It’s pretty.

There is nothing you can do to affect the mountain, at least not that anyone has discovered.

Now, obviously this is the sort of thing that would get called “not a game.” And in fact, while praising it, some get perilously close to saying exactly that, in academic lingo:

Just to be clear: Mountain is not a text. It shouldn’t be treated as one. Mountain is best understood as an exercise in form — it’s a small, contained work that depicts and explores a mountain as an object.

At Critical Proximity I pointed out that the avant-garde/art/whatever games would have been called “formalist” in any other medium, so I like this observation.

Here’s Brendan Keogh reacting negatively to Mountain:

I thought I would write a piece about how it makes a point of nothing-ness in a really interesting way. In its menu, where it explains the controls, both ‘keys’ and ‘mouse’ are said to do “NOTHING” despite this being clearly false (keys play musical notes and the mouse rotates and tilts the mountain). It seemed like an explicit commentary on videogames and nothingness, and I thought that would be cool.

But I found it so boring.

Interactivity again

In the last few days I have been writing on and debating “interactivity.” So let me offer up an alternate formulation here that ditches the word altogether.

First, let’s look at a dictionary definition of interactivity:

interactive (ˌɪntərˈæktɪv)

— adj

1.

allowing or relating to continuous two-way transfer of information between a user and the central point of a communication system, such as a computer or television

2.

(of two or more persons, forces, etc) acting upon or in close relation with each other; interacting

Let me hasten to point out that this is far from the only definition out there; I am picking this one in particular just because of two phrases contained therein:

“two-way transfer”

“in close relation”

These two pretty much encapsulate the debate over “strong” and “weak” interactivity, or “exploratory” versus “ontological,” or “gamey” and “not a game” or whatever.

This is where we see people on the one side discussing feedback, mechanics, and other words with the same clinical detached tone as “two-way transfer.” And two-way is such a binary simple thing, absolutist and firm: if it’s two-way it’s one thing, if it’s one-way it’s another. Nice bright line.

And on the other side we see people fetishizing the word “immersion,” talking primarily from the point of view of the player’s perception, eschewing essentialism like the above. It’s about mental constructs, Kieron Gillan saying things like

This makes us Travel Journalists to Imaginary places. Our job is to describe what it’s like to visit a place that doesn’t exist outside of the gamer’s head — the gamer, not the game, remember. Go to a place, report on its cultures, foibles, distractions and bring it back to entertain your readers.

Inner lives

Let me suggest that we can think of these as two different preoccupations.

An interest in the inner life of subject A (the object)

An interest in the inner life of subject B (the player)

There is a third actor in the mix, at a minimum: the creator of the object. But let’s leave that dynamic aside for a moment.

What is “life?” Ah. It’s basically autonomous movement, in this conception. It is the turning over of ideas and tumblers, the movement of muscles and theses. Everything has it, in this sense, but it grows increasingly alien as we move farther away from our own subjective experiences. And it also does come in degrees; some things and some people simply don’t engage in this turning over, this tumbling. Some are quiescent. I am quiescent, when I watch, say, Suits on USA, or Bring It On. Under varying circumstances, we (or anything) are excitated by signal, by story, or not.

It is very hard to perceive the inner life of a rock, and those who do are (ironically) deeply “formalist” and “essentialist” and all those other nasty words, because they’re scientists who have gone and learned geology and therefore understand the rock on its own terms. But sometimes maybe there’s a story told to us that includes some of the point of view of a rock, and then we can start to build a mental model. Think of these explainers and storytellers as Travel Journalists to a Real Place, perhaps.

Some things give you high signal views of their inner lives. Some give you low signal. (That you can perceive, anyway; we aren’t equipped to see many of the signals given by a rock). Similarly, since this is a binary relationship, there are signals we are giving off to the rock. It’s very hard to tell if the rock cares, though we may perhaps notice that it warms up when we sit on it.

Critics who want to use the term interactivity to focus on the subjective experiences of players, who see interactivity in every cognitive interaction with a text, who want to write games criticism that is personal, are all focused on the inner life of the player. This is a very important thing to focus on; the much-maligned allegedly formalist game grammarian would tell you that the canvas of a game is the human mind.

Critics who are interested in game grammar, though, are interested in the inner life of the object. They get a lot less interested when the object doesn’t have much of an inner life, when it’s not turning over ideas in its head, when it’s not evolving, when it does not react.

Simulation versus stagecraft

People who are interested in the inner life of the player are going to tend to prioritize signal that excitates the player. People who are interested in the inner life of the object are going to be interested in signal about excitation within the object. We have terms for these.

When a game object is ticking over, turning, tumbling, moving, living, it’s called “simulation.”

When a player is ticking over, turning, tumbling, moving, living, we usually call it “thinking” or “reacting” or “cognitive processes.”

When a game object is not actually exhibiting much of an inner life, but the player is getting a signal anyway, intended to provoke a player’s inner life, we call it “stagecraft.”

Critics and thinkers who are interested in the inner lives of the game are often disdainful of stagecraft. It’s “faking it.” You’re talking to the dead, after all. Now, nothing is entirely “dead” in that sense (everything has some amount of inner life) but there’s a threshold there where they see themselves betrayed. They can tell at a glance that the apparently static output of a Mandelbrot set has a rich inner life, and that Conway’s Game of Life does too, and that a Hardy Boys novel has less.

On the other hand, designers who are more interested in simulation are often accused of “ant farming,” of non-commercial work. They frequently fall into the trap of making games with rich inner lives are are opaque to the player:

It has to be visible and responsive to players. This includes exposing causality. Otherwise, it might as well be random.

- UO’s Resource System, part 3

Because of this, it is usually considered best practice to make sure to have the right amount of stagecraft present to get across the inner life of the object.

People interested in the inner life of the player don’t really care whether the signal from the object is actually reflective of what is going on inside the object. Otherwise, they wouldn’t love Final Fantasy games. Their core preoccupation is what goes on inside themselves. After all, the signal they are getting from stagecraft may prove just as, if not more intriguing than the actual inner life of the object.

In point of fact, it is almost certainly far more digestible than the actually alien things that are going on inside the object. It will be presented in familiar media, in familiar “language” in order to communicate and bridge the gap. In effect, stagecraft is prepackaged provocations for an inner life. Stagecraft is usually designed very intentionally to create a specific inner life in the player, to shape them in specific ways. We design stories in order to excite only these neurons, not those. It’s far more predictable than the excitation provided by the actual inner life of an object, which might provoke reactions we don’t want.

And people interested in the inner life of the player then say things like

when people say games need objectives in order to be ‘games’, i wonder why ‘better understanding another human’ isn’t a valid ‘objective’

games need ‘challenges’ and ‘rules’, isn’t ‘empathy’ a challenge, aren’t preconceptions of normativity a ‘rule’

- Leigh Alexander on Twitter, quoted in “A Letter to Leigh”

Back to the mountain

Mountain has an inner life. We think. There is a fair amount of stagecraft there presenting it. Trees, clouds, etc. Gosh, say the signals. There’s something going on this mountain.

The player playing it also has an inner life. They wondering about this mountain, which is giving off all these signals. It’s looking at this mountain, much like it might look at one in real life. You could move around a real mountain. You could stand there and watch trees grow on it, or clouds shadow it, or seasons change. You could even play chimes at a real mountain.

The bridge between the two is very tenuous, though. Both lives are alone together. They aren’t really communicating with one another, they are just throwing off errant signals. The player has no way to direct these signals towards the mountain with intentionality. We don’t know if the mountain can hear them anyway. There is a glass wall separating these two lives.

When most people — not high-falutin’ critics, not erudite scholars — say the word “interactivity” they mean reaching through that wall. There’s another word for that process…

Mountain is in some ways a direct challenge to those who see interactivity as about the player’s inner life. It doesn’t provide a lot of support for it. In in fact tries pretty hard to give you just about the same sort of support you get from going outside. To people who are used to being spoonfed crafted signal, this is a big leap.

To people interested in the inner life of the object, though, it also lacks enough signal. There’s an inner life in there, there’s a machine or a beating heart. Stuff wouldn’t change on the outside if not. We just can’t tell if it’s a set of sine waves or something more complex. How alive it is, or whether it’s actually pretty dead. (The natural next impulse of someone interested in the inner life of the mountain will be to decompile it and dissect it on a stainless steel table.)

Mountain leaves you with your inner life, facing actual alien phenomenology. In other words, Mountain is a challenge to your empathy.

July 9, 2014

Interactivity

One of the things I have seen a lot among younger critics who prefer narrative-centric approaches in their games is an emphasis on questioning definitions of “interactivity.”

Here’s the thing: noticing that the act of interpreting something is effectively “interactive” is not a novel observation.

To start with, it is a rather fundamental notion in learning theory in general. For example, it’s a cornerstone experimental result in studies of how learning to read in the first place works.1

But let’s jump to art rather than cognition; the premise that you can be changed by, say, a book, is hardly new.

Beginning with the exploratory

It’s been discussed in literary theory for decades if not centuries. Horace in Ars Poetica argued that poetry should instruct and delight; instruction is fundamentally “interactive.” The Romantics were discussing these ideas in the late 1700s and early 1800s, and is implicit in Wordsworth’s Preface to the 1802 Lyrical Ballads:

the human mind is capable of being excited without the application of gross and violent stimulants… It has therefore appeared to me, that to endeavour to produce or enlarge this capability is one of the best services in which, at any period, a Writer can be engaged; but this service, excellent at all times, is especially so at the present day. For a multitude of causes, unknown to former times, are now acting with a combined force to blunt the discriminating powers of the mind, and unfitting it for all voluntary exertion to reduce it to a state of almost savage torpor… To this tendency of life and manners the literature and theatrical exhibitions of the country have conformed themselves. The invaluable works of our elder writers, I had almost said the works of Shakespeare and Milton, are driven into neglect by frantic novels, sickly and stupid German Tragedies, and deluges of idle and extravagant stories in verse. When I think upon this degrading thirst after outrageous stimulation, I am almost ashamed to have spoken of the feeble effort with which I have endeavoured to counteract it…

And of course, clear back in 500BC with Simonides2 we had someone saying that this applied in just the same way to poems or paintings.3

These days science is in on the act too. You’re likely to get pointed at the work of Robert Gerrig4 but he’s building on results in psychology that go back to the 1930s, when it was noticed that where a reader was from profoundly impacted their interpretation of a text. Gerrig conducted experiments showing that unquestionably, on a cognitive and psychological level, readers bring a huge component of the act of interpretation or indeed even comprehension. When Gerrig et al say

In light of this evidence, we propose that fiction, like fact, necessitates a willing construction of disbelief…

they are not so far off from Coleridge desiring

…to transfer from our inward nature a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith.

In the world of hypertext criticism, there was active discussion of the issue of subjecting oneself to an all-powerful narrator; Jay Bolter, for example, was rather critical of the very notion of immersion, arguing that immersion in the sense of passively accepting what the author tells you is what “bad” readers or “lazy” readers do, and condemns writing meant for pure escapism that is written according to conventions of genre.5

It’s even been thoroughly looked at in the context of virtual realities and simulated environments and games by scholars such as Marie-Laure Ryan.6 Ryan even provided us with helpful terms for discussing the concepts of “interactive that is interpretive” (she terms it “exploratory”) and “interactive that changes things” (her term is “ontological.”)7

If we want something a tad farther along this scale than purely interpretive, it is trivially easy to draw connections between, say, Dear Esther or other experiential work that relies primarily on player “assembly and interpretation” and say, the poems of Gertrude Stein. As she says in Tender Buttons,

Why is the name changed. The name is changed because in the little space there is a tree, in some space there are no trees, in every space there is a hint of more, all this causes the decision.

That frankly sounds an awful lot like a lot of experiential criticism of certain videogames.  I mean, Stein even said she was after capturing “moments of consciousness” which sounds rather like what Tale of Tales says when they use the term “notgame.” Or maybe they mean “emotions recollected in tranquillity.”8

I mean, Stein even said she was after capturing “moments of consciousness” which sounds rather like what Tale of Tales says when they use the term “notgame.” Or maybe they mean “emotions recollected in tranquillity.”8

I could go on and on. The assumption of “exploratory interactivity” is basically rampant throughout the arts. So I, at least, take this part for granted, and for that matter, don’t think videogames as a form do anything at all new or special here. Not even notions like Bogost’s procedural rhetoric are outside the mainstream current of thinking on this front: there are elements in a work, these are subject to interpretation, the audience all sees it slightly differently, the audience’s world may change a bit, hurrah.

When supposedly formalist critics say things like “that isn’t very gamelike,” “not very interactive,” “on the experiential side,” and so on, what they tend to mean is “there’s very little ontological interactivity.”

Starting to get ontological

It’s important to realize that given the observation, there is still quite a lot that is interesting in looking at work in various mediums that uses the ontological form of interactivity: that which requires the reader/viewer/player to do more than assemble mental models, but to make a choice which causes a differing output in the work.

This is not new either.

After all, Homeric verse was declaimed, and likely altered on the fly as it was misremembered, changed around based on audience response, etc. Those of us with a literary background are getting tired of citing Julio Cortázar’s Rayuela, Carolivia Herron’s Thereafter Johnnie, or Nanni Balestrini’s Tristano.

It’s been done in theater. A lot. A typical example cited is Ayn Rand, of all people, with her play Night of January 16th. In this courtroom drama, some audience members join the jury and vote on whether the accused in guilty. The play has multiple endings. But you could go for a less interactive form, and cite clapping for Tinkerbell in the stage version of Peter Pan. Indeed, J. M. Barrie rather breaks the fourth wall in the original book text as well:

His head almost filled the fourth wall of her little room as he knelt near her in distress. Every moment her light was growing fainter; and he knew that if it went out she would be no more. She liked his tears so much that she put out her beautiful finger and let them run over it.

Her voice was so low that at first he could not make out what she said. Then he made it out. She was saying that she thought she could get well again if children believed in fairies.

Peter flung out his arms. There were no children there, and it was night time; but he addressed all who might be dreaming of the Neverland, and who were therefore nearer to him than you think: boys and girls in their nighties, and naked papooses in their baskets hung from trees.

“Do you believe?” he cried.

Tink sat up in bed almost briskly to listen to her fate.

She fancied she heard answers in the affirmative, and then again she wasn’t sure.

“What do you think?” she asked Peter.

“If you believe,” he shouted to them, “clap your hands; don’t let Tink die.”

Many clapped.

Some didn’t.

A few beasts hissed.

The clapping stopped suddenly; as if countless mothers had rushed to their nurseries to see what on earth was happening; but already Tink was saved.

As in the case of the exploratory angle on interactivity, I think there’s ample evidence that outside of games there’s a robust tradition of what might be termed “mild” forms of ontological interactivity. I say mild, simply because most of these examples are limited to simple branches:

A Choose Your Own Adventure story is actually a fixed set of stories glued together through commonalities in plot.

Most experiments in random ordering fall back on what might be termed an impressionist approach; your overall perception of the narrative is not significantly different based on the order.

There are exceptions, but thinking here of stuff like Afternoon: A Story;

The reader of a classical interactive fiction–like Michael Joyce’s Afternoon–may be fascinated by his power to control the display, but this fascination is a matter of reflecting on the medium, not of participating in the fictional worlds represented by this medium. Rather than experiencing exhilaration at the freedom of “co-creating” the text, however, the reader may feel like a rat trapped in a maze, blindly trying choices that lead to dead-ends, take him back to previously visited points, or abandon a storyline that was slowly beginning to create interest.

- Ryan, http://www.gamestudies.org/0101/ryan/

or Tristano…

The experience wasn’t fun, or moving, or riveting, but as I forced myself to slog through its juxtapositions and disjointed scenes, I started wondering if there was an idea embedded in the project’s architecture. Through its play with contingency, variation, and instability, Tristano forces us to talk about it like we talk about the world and about politics. It situates us in a specific viewpoint—different from but no less legitimate than anyone else’s—and then challenges us to seek out the common ground that makes discourse possible.

http://www.blunderbussmag.com/coping-with-chaos/

Or the aforementioned Rand play, where the actual point of the play is apprehended by seeing both endings. Perhaps a linear version of this might be Bierce’s “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.”

What lies beyond

As Ryan puts it,

Interactivity is not merely the ability to navigate the virtual world, it is the power of the user to modify this environment. Moving the sensors and enjoying freedom of movement do not in themselves ensure an interactive relation between a user and an environment: the user could derive his entire satisfaction from the exploration of the surrounding domain. He would be actively involved in the virtual world, but his actions would bear no lasting consequences. In a truly interactive system, the virtual world must respond to to the user’s actions.

Or as Bolter says,

The computer therefore makes visible the contest between author and reader that in previous technologies has always gone on out of sight… this traditional belief in the fixity of the text cannot survive the shift to the electronic writing space.10

In mild forms of ontological activity, the world responds only by unveiling yet another predetermined brick in an edifice of authorial logic. This is why we have some game critics claiming that all systems, all artistic works, are in fact built of false choices, of the tyranny of the author.

But there are many games where what the player brings to the table is not “choice” of using a tiny set of verbs on a tiny set of largely irrelevant props, all aiming in the end towards the same predetermined authorial lesson. Systems can be designed for authorial imposition — Wordsworth’s or Horace’s intent to educate and illuminate — or for players to express, create, and even innovate. It is here where games like The Sims, Eve Online, Minecraft, Universalis, Dwarf Fortress,11 and even less “free” designs like Core Wars lie. And there is a case to be made that in that space are things that only games can do.

The main reason why critics keep thinking in terms of linearity, exploratory interactivity, and false choice is because that’s what most of the games they have played offer.

An article like Beirne’s portrays “ye olde interactivity paradigm” as a) the notion that interactivity is the unique quality of games, and b) interactivity is “pressing a button in a game to make stuff happen.” As the above hopefully shows, he’s correct to say that both are false, and correct to say (as he does) that he’s built a strawman. But along the way, “make stuff happen” is being erased.

And if we’re talking about “ye olde” definitions of interactivity, it doesn’t hurt to point back at Crawford, kind of the granddaddy of all the formalists in videogames, who defined it as

A cyclic process between two or more active agents in which each agent alternately listens, thinks, and speaks—a conversation of sorts. In this definition, the terms listen, think, and speak must be taken metaphorically.

When people seem like games fundamentalists, they are stretching for greater agency, not less. They are trying to identify the structures that lead to this strong ontological interactivity. When they talk about systems, they are reaching for realer choices, not false ones. When they minimize narrative, they are saying they want to think for themselves more, rather than be told what to think. When they say “interactivity” they mean freedom from those thousands of years of mainstream cultural current that say you must be lectured to. It is not an accident that self-determination theory is being found to have great applicability to game systems design.

None of this means that exploratory interactivity is bad. Or that mild ontological interactivity is bad. They’re not. There’s nothing wrong with making an exploratory interactive text and calling it a game. There’s also nothing wrong with doing fairly bog-standard literary exegesis work on games like that. But they are found in many media. Strong interactivity, though, is found in fewer places, mostly tied to improv: music, comedy, roleplay, games.

Which means that focusing on this powerful and relatively rare tool, one that has only been able to come to fruition fully on a digital stage, is actually a really valuable effort, and not one that deserves denigration as sterile formalist wankery.

In fact, one might even make the argument that flowerings of ontological interactivity layered atop exploratory games — as in the case of speedruns, glitch hunts, subversion such as pacifist FPS play12 — are signs of the ways in which players themselves are engaged in this same exploration, like water that naturally seeks to break out of its prescribed channel.

So where does that leave us? Well, Bolter mentions that Harold Bloom believed13 that

each poet must misread his or her predecessors in order to create a new text under their otherwise crushing influence.

To me, that feels very much like the enterprise that many game critics are currently engaged in.14

Such as, for example, the work by Rumelhart et al starting around 1977. For examples of experimental results, see http://psych.stanford.edu/~jlm/papers/RumelhartMcClelland82.pdf. ↩

Well, at least according to Plutarch. We don’t actually have a lot of Simonides left. ↩

ut pictura poesis as Horace had it. ↩

such as http://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/BF03210803#page-1 ↩

“Losing oneself in a fictional world is the goal of the naive reader or one who reads as entertainment. Its is particularly a feature of genre fiction, such as romance or science fiction” — page 155 of Writing Space. ↩

A good synopsis of her work can be found here: http://www.humanities.uci.edu/mposter/syllabi/readings/ryan.html ↩

This builds on the work of Espen Aarseth in Cybertext, but I find Ryan’s formulation more succinct. ↩

Wordsworth. ↩

or “squinteractive” as Stephen Beirne calls it in his piece here: http://normallyrascal.com/2014/07/07/ye-olde-interactivity-paradigm/ when he states “I’m going to try to move away from the application of interactivity to almost exclusively mean ‘press button to make stuff happen’ by giving a name to this old critical/design model. I’ll call it ‘squinteractivity’, because it only makes sense if you squint really hard. Also I suppose because it offers only a very narrow perspective.” ↩

Writing Space again, pp 154-155 ↩

whose most recent patch note included the marvelous statement “Some dwarves have life-long dreams and it is possible for them to recognize that they’ve accomplished the ones relating to skills and family. They cannot yet realize their dreams of taking over the world.” ↩

see for example, Conscientious Objector. ↩

all the coolest quotes in Writing Space are indeed on pages 154-155! Or rather, all the stuff that has held up the best, anyway… ↩

The preceding post expanded from an abortive tweet that was kinda grumpy. Sorry.  ↩

↩

June 19, 2014

Privateer Online

In the wake of the excitement over No Man’s Sky and its procedural worlds, I thought that it might be a good time to tell some of the story around the version of Privateer Online that I worked on, that never saw the light of day.

In the wake of the excitement over No Man’s Sky and its procedural worlds, I thought that it might be a good time to tell some of the story around the version of Privateer Online that I worked on, that never saw the light of day.

After I moved off the UO team, I worked on several MMO concepts for Origin. The mandate was explicitly “come up with something that we can make using the UO server and client pretty much intact, without big changes, because we need it quick.” This limited the possible projects enormously, of course.

So I started developing one-sheet concepts that fit the bill. None of them got farther than a few pages, and the idea was to give execs some choices on what we would go make.

There was Mythos, which eagle-eyed Origin fans even noticed the domain registration for. This was set in the real world, in the mythologies of every culture. Basically, it was like LegendMUD but only set in the ancient period.

There was a pirates/seafaring one one. The idea was to make boats be a single tile in size, with a “scale change” when you got in a boat (kind of like Seven Cities of Gold). That way we could do ship to ship combat in a reasonable way for the time and in 2d.

There was a pirates/seafaring one one. The idea was to make boats be a single tile in size, with a “scale change” when you got in a boat (kind of like Seven Cities of Gold). That way we could do ship to ship combat in a reasonable way for the time and in 2d.There was something around vampires. I don’t remember it very well, but Buffy was on and Anne Rice’s book were popular.

Mythos was the one that execs liked out of that set. Oh, there were more. I vividly remember a phone call where an exec and I were talking with a Hollywood agent as he tried to persuade me that Leave It To Beaver was due for a comeback, or that Baywatch Online was a good idea.

Right after UO shipped, Damion Schubert and I had collaborated on a pitch for a 2d space MMO, because Origin was wondering what the followup would be. This pitch wasn’t ever delivered. We walked in to present it, and were told “we’re doing UO2.” The programmers on the team has pitched a post-apocalyptic idea, and when they heard that it wasn’t happening, they all quit. This is why I was the only UO vet on Second Age.

If I recall correctly, this sci-fi pitch was sort of MMO meets Star Control meets Starflight. The game idea didn’t get heard by anyone, he went off to do UO2, and I went off to do Second Age.

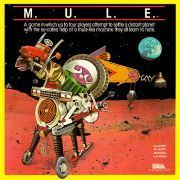

When I was asked what I really wanted to make, my answer was immediate: M.U.L.E. Online. The original M.U.L.E. is my favorite game of all time, and it seemed to me that it was perfect for going online. The IP was going fallow at the time, the original designer (Dani Bunten) had passed away, and I was at an EA studio. But there were legal entanglements with the family, and there was no way to make it happen.

When I was asked what I really wanted to make, my answer was immediate: M.U.L.E. Online. The original M.U.L.E. is my favorite game of all time, and it seemed to me that it was perfect for going online. The IP was going fallow at the time, the original designer (Dani Bunten) had passed away, and I was at an EA studio. But there were legal entanglements with the family, and there was no way to make it happen.

So I started sketching out something else, codename Star Settlers. It still had the idea of colonizing planets, but instead of people on one planet, it was thousands of planets, procedurally generated. You started out on one, a small MMO world (think the size of one UO city). You sent off an exploration ship and it would find one for you and generate it. You would go to it, slay monsters, etc, and if you managed to pacify it, you could build on it.

Every planet had its own resource mix, so you would want to constantly go outwards and pioneer. If a planet was “used up” or nobody tended to go back, we’d just “lose the spacelane to it” and erase it, to make room for more. The hope was that someday even the starting worlds would get abandoned and replaced.

Mythos and Star Settlers were the final two candidates, and when I was asked which one I preferred, I picked Star Settlers.

First exec comment was “hate the name. And we have a powerful science fiction IP in-house! This should be in the Wing Commander universe. Maybe Privateer.”

This of course blew up a huge portion of the design. There’s a lot of lore in the WC universe. Star Settlers worked in part because it literally handed galactic history over to the players.

Second exec comment was “this is a Wing Commander game! It’s got to have space combat. And be in 3d.”

That blew up most of the rest of the design. And the whole starting premise of “have somehting to ship within a year” that was the start of the entire project. (This latter sequence of events has happened to me more than once in my career. “We need something quick! Re-use tech!” “This is cool! Switch to better tech!” “Uh, didn’t we need something quick?”)

There had been multiple tries at getting a Privateer Online/Wing Commander Online going by that point. All of them came from people over in the WC group. Some of them had gotten pretty far — piles of artwork, design work, and even some tech. (I think fansites say there was only one prior try, but I think “my” PO was actually something like number seven as we counted them internally. Most didn’t get very far).

This ended up being a case where the Lord British Productions team actually ended up getting a different team’s IP greenlit for their own use. Needless to say, this ticked off some folks on the Wing Commander side. One of them came in to interview to switch teams and started out by saying “what makes you think you are qualified to make a Wing Commander game?” I replied with “I’m not.” We ended up as good friends.

The Privateer Online team

The resultant team never jelled entirely, and the design suffered from that a lot. We ended up producing a ridiculously ambitious design bible (a “DDR” in OSI lingo) that was lavishly illustrated, and a prototype. Lots of stuff was overcomplicated. In hindsight, that’s kind of classic Origin, actually.

Anyway, some of the features of that Privateer Online:

You could sit down at the prototype and enter a planet number, and it created a planet for you. Just terrains, colored textures, etc, but every planet was radically different. You could run around it in 1st person 3d. I remember that 666 was hellish, which struck us all as funny. This system was using various Perlin noise generators to create heightfields, but we didn’t have artwork in, except maybe for your spaceship sitting there.

There was rather fun and slick mouse-controlled space combat, with multiplayer dogfighting. Some asteroids to dodge, etc.

We’d designed a ship customization system that was more or less fractal. You could pick a chassis, and each chassis had attachment points for Size A things. Size A things were guaranteed not to intersect because that’s how we built the chassis. Size A things had size B attachment points, and because Size B was always half the size of Size A, they also always fit, and so on.

The same modular idea extended to the ground-based game, where you could build up towns, mining facilities, factories, etc. Stuff plugged together — you had to build transport lines between the different sorts of buildings to get stuff working, as I recall. Sort of like supplying power to buildings in SimCity. The resources extracted would be different per planet, so there’d be interplanetary trade. And you’d get ambushed in space, because space was where the privateers would be.

There was a HUGE PILE of lore written (I didn’t write any of it… WC vets did). Some of it is available over at the Wing Commander CIC site. Probably the most illuminating for readers would be the fictional setting, which is in this Word doc.

We demo’ed it at an Origin all-hands meeting. People liked it. The design doc was circulated around EA, and we were even invited to Westwood Studios (the makers of Command & Conquer) to talk MMOs with the team there. We went out there, shared some knowledge, and marveled at the creepy office. It was built in a former defense contractor’s building. There was one phone, at the front, and if you got a call, it was announced over the loudspeaker and you had to walk to the front to take the call in public. There was one Internet connected computer, in the lounge, and you were supposed to browse in public. It was all very… Big Brother.

And then Privateer Online was cancelled in favor of Earth & Beyond. From Westwood.

There’s a ton of stories to tell around all that — it happened nearly simultaneously with Richard leaving Origin — but this post is really about the game, because nobody ever officially knew it existed (though there’s an OK article over here about it). I hear that some folks have that big design bible — I don’t, I scrupulously left it behind when I left OSI. I am pretty sure that if I read it now I would be horrified.

That said, a core group from that team went on to do Star Wars Galaxies, and you can see some of the ideas reappearing. The fractal terrain and other design elements in SWG are worth a blog post of their own someday.

A few years later, when Origin was shut down, there was a big bonfire party. Copies of the Privateer Online DDR, along with those from many other Origin projects that never saw the light of day, were used to fuel the flames.

We all got t-shirts that said “We Created Worlds.”