Raph Koster's Blog, page 11

April 20, 2015

SWG’s Dynamic World

This post is dedicated to the memory of John Roy, lead environment artist on Star Wars Galaxies. Help out his family here.

This post is dedicated to the memory of John Roy, lead environment artist on Star Wars Galaxies. Help out his family here.

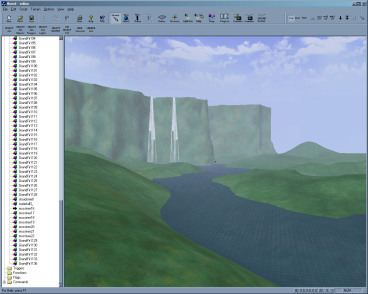

Let’s do some math. Let’s say that you need to have a pretty big world: sixteen kilometers on a side, and made out of tiles.

A tile needs to know what texture it is. That’s one byte. Not much, right? You only get 256 tiles on a planet, though, which isn’t a lot.

But wait, we can add some variety there, by putting in some colors. We’re in 3d, right, so we can tint the tiles slightly and get variation. It’s normally three bytes to apply a color, but let’s instead just say that each planet has a fixed list of colors, and you can have 256 of them, and that way each tile can look up into a list of colors and we only need one byte.

Oh, and it’s a 3d game heightfield, so we need to know what the elevation of the tile is! We’ll just say that there are only 256 levels of height, and that way we can keep it at a nice conservative three bytes per tile.

That’s good, because we need a lot of tiles. They’re one meter on a side. So that means that for a planet we need 16,384 just to make one edge. We need 16,384×16,384 to lay down the whole world.

That’s good, because we need a lot of tiles. They’re one meter on a side. So that means that for a planet we need 16,384 just to make one edge. We need 16,384×16,384 to lay down the whole world.

That’s 268,435,456 bytes for this world. Of course, we need ten planets, not one. So, that’s more like 2,684,354,560 bytes. Nobody uses bytes, so that’s 2,621,440k. 2,048mb. 2.56 gigabytes, uncompressed.

That’s… not going to fit on a CD. I mean, that doesn’t include any art yet.

DVD drives weren’t yet widespread in 2003. In fact, taking up 2.5 gigs of space just for maps was unheard of.

The solution to that problem didn’t just let us ship Star Wars Galaxies, it also unlocked everything from player housing to crafting to giant Imperial vs Rebel battles.

Patent disclaimer

Before you read any farther, you should know that Sony Online actually patented some of the technology that I am going to describe. If you are someone who should not be reading technology patents, you should stop now.

Origins

I’ve described before how the abortive Privateer Online worked. That game, like other spaceflight classics, was intended to have thousands of worlds. This was going to be accomplished using a neat quirk of how random numbers work on computers: the fixed random seed.

Very early experiments

You see, computers don’t actually generate random numbers. They generate predictable numbers using a seed value. To make the results more erratic, you constantly change the seed value — usually by using the current time down to the millisecond or something. There are many routines used in order to make numbers from a seed, but if you take the exact same routine from one computer to another, and then give it the exact same seed you’ve used elsewhere, you should, generally speaking, get back the same random numbers, in exactly the same order.

This is basically a really cool way to compress information. It’s not that different from knowing that given the formula to calculate pi, everyone will be able to get the exact same result out. So it’s a lot easier to just hand around a tiny formula than it is to try handing around a zillion individual digits. The formula fits in a few bytes; the individual digits take up a lot of space.

Each planet in Privateer Online used a single seed, and from it, we picked things like sky color, tile colors, and generated a whole map. So one seed value was enough for a small planet.

But it had to be small — the thing is that there are a lot of randomness generation routines for terrain out there, and they all sort of get… “patterned” after a while. If what you roll up is gentle rolling hills, you are going to get gentle rolling hills fairly consistently. If you have spiky mountains, well, that’s what you are going to have everywhere.

When we got t

When we got t o doing SWG, we had this stuff on the brain, of course. But we also saw that other projects at SOE were doing maps that were meshes. In some cases, they were actually sourced from procedural terrain generators, very fancy ones that you couldn’t run in realtime, and that involved a day-long baking process as the resultant maps were turned into meshes. Once they were meshes, you could run compression and level-of-detail routines on them to reduce their size… but there was still no way to get truly big worlds.

o doing SWG, we had this stuff on the brain, of course. But we also saw that other projects at SOE were doing maps that were meshes. In some cases, they were actually sourced from procedural terrain generators, very fancy ones that you couldn’t run in realtime, and that involved a day-long baking process as the resultant maps were turned into meshes. Once they were meshes, you could run compression and level-of-detail routines on them to reduce their size… but there was still no way to get truly big worlds.

Actual size isn’t the only factor, of course. The granularity of the world matters too. You can have a 16km x 16km world with tiles that are a kilometer in size, and it’s going to take up the same data space as a 16 meter by 16m world. You can also have a game world like that of Eve Online where the vast vast majority of it is empty space; they procedurally generated theirs too, and as a little homage to Douglas Adams, the seed value for their procedural galaxy is the number 42. And it matters whether you can change this world; if it’s rolled up from a seed value, then you can’t exactly go carve a hole in it without storing the actual map in memory. This leads players to spend lots of time debating the right way to measure game world size.

Generating worlds, then, is kind of old hat. The harder part is, how do we make a world as living as possible, one that can change and evolve at a high level of detail, while still having plenty of room?

The layering tool

The tool

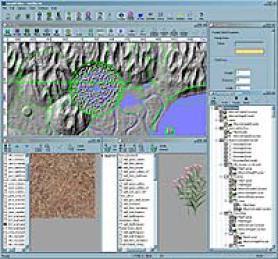

We actually published a very layman’s version what we did for SWG on the game’s website in advance of launch. You can still find the article on the Wayback Machine. The heart of the idea was marrying Photoshop layers with procedural generation. Here’s a screenshot of the tool from that article.

Shapes like ellipses, circles, and boxes are easily described mathematically. You can say “run this rule when you’re inside this circle, and this other rule when you’re outside of it.” You can say things like “run one rule that gives you gentle changes. Now use that rule as a blend value for how much of this mountainous rule to blend onto a third rule that is grassy plains.” You can see several of these circle rules on the map.

We never did do river generation, though; as a result, the rivers all tended to form loops, because that was what we could make. Water was a simple water table height, and anything under it was underwater. We also added the ability to insert “water sheets” at arbitrary heights so we could do things like the river in Theed, up top of the cliff. Early on we had big dreams about maybe doing underwater play, but that never even made it onto the schedule since it was so improbable.

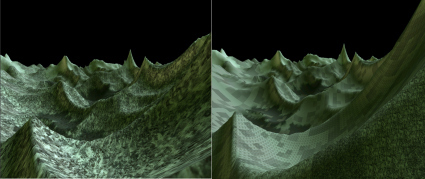

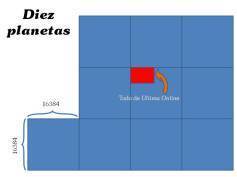

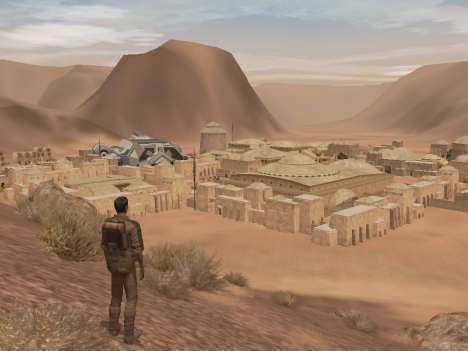

Very early work on Tatooine, showing the terracing technique described here

To give a realistic example: on most all the mountainous areas, we wanted there to be ledges available pretty often. Ledges and “terracing” were easy to create; just say that whatever the mountain routine output, you clamped to a multiple of something. So instead of getting “1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ,6 ,7, 8, 9,” you’d get back 1, 4, 8. But if you do that across the entire map, you get something that looks like wedding cake, plus the areas are dead flat. Ah, if you say “but you should only run that rule in some places, and we’ll decide those places by taking another rule and checking for ‘high spots'” then you get flattening happening in little islands. So you stack the rules in order: Plains. A filter to put mountains only somewhere. Mountains. A filter to put ledges only some places. Ledges. A “gentle wavy” one to make the ledges not dead flat, applied across the entire map. And finally, a circle for a flat area where we need to build, say, Dee’ja Peak. Oh, and we used similar rules to put down color washes; terrain textures, which in some cases came with the wavy grass, and could also come with bumpmaps; trees, plants and rocks; even some sorts of points of interest.

You can in fact stack quite a lot of rules like that, and they still take up very little storage space. The beauty of the rules is that they save out to little text files; a planet on SWG was usually on the order of 16-32k of text. The beauty of something like Perlin noise as a terrain generator routine is that you ask for the elevation result at any arbitrary coordinate. You don’t have to generate the terrain “in order” and it’s not dependent on what is next to it. (I had met Ken Perlin, the inventor of Perlin noise, at a conference a while before, so we flew him out to the office and he helped optimize our algorithms).

When we only had one tree

This meant that we could use it for graphical level of detail too. Those of you who played may recall the “terrain detail” slider in options, which was capable of bringing your machine to a crawl. At max, what it did was query the elevation for every coordinate, out to your draw distance. At lower settings, it instead started skipping points: every other one, to start, but eventually computing only one out of every 8 or 16 elevations. This resulted in less terrain tiles, way out there, and you could see “popping” as you moved closer and more heights were computed, changing the profile of mountains. It was way way worse with trees, though, because whole forests would pop into view when they were finally above the generation threshold.

Nobody could actually run at max detail and get a decent framerate, at the time. The hope was that as machines grew more powerful, you’d be able to. These days, you could probably just compute the entire planet and put it in RAM on a beefy enough machine. We took our mark eting screenshots at everything maxed, and just stood still while taking them. (Our tech director, Jeff Grills, gave a presentation at an AMD event on the challenges of rendering and performance; you can read it here, if you are technically inclined.) Even then, as many players have noticed, the quality of the graphics seemed lower between the early shots and later ones — the E3 demo had more shaders on everything, and better lighting in general. (The drop-off was so big that Gabe of penny Arcade actually wrote a post complaining about it). Most players don’t know it, but the bigger loss was actually on characters, not terrain; early characters looked way cooler, but we couldn’t afford the draw calls or something.

eting screenshots at everything maxed, and just stood still while taking them. (Our tech director, Jeff Grills, gave a presentation at an AMD event on the challenges of rendering and performance; you can read it here, if you are technically inclined.) Even then, as many players have noticed, the quality of the graphics seemed lower between the early shots and later ones — the E3 demo had more shaders on everything, and better lighting in general. (The drop-off was so big that Gabe of penny Arcade actually wrote a post complaining about it). Most players don’t know it, but the bigger loss was actually on characters, not terrain; early characters looked way cooler, but we couldn’t afford the draw calls or something.

Challenges

Procedural environments have a sameyness to them, though. If you have the rules tweaked enough, they can actually add more detail than a human will, because the algorithm isn’t bound by time constraints. But you need quite a lot of fine detail variation on the rules to get back to where the terrain really does surprise you. Like the real world, most of it is fairly bland. (In fact, one of the classic videogame map tricks is to heighten slopes dramatically compared to the real world; after all, most real world slopes are much gentler than 30 degrees!)

John Roy

So artists used to handcrafting environments had trouble with this tool for quite a while. I worked for months hand-in-hand with the late John Roy, the lead environment artist, to tweak our best practices and our basic understanding of how to use the rules. John passed away a few months ago, and if you were an admirer of the eventual result in Galaxies, I’d like to urge you to donate to the memorial fund for his family.

The use of circles and boxes as rules allowed artists to craft the very specific film locations to a pretty huge degree of accuracy, but it did call for iteration: trying different seeds until you got something that matched what we had seen in the film. Also, there was a performance limit on how many rules you could pile into a map. If you hit hundreds, it would slow down the calculation as the code had to check, for every point, whether it was under the influence of a given rule (imagine hundreds of point-in-circle tests for every point on the map). So they were under budgets as far as rule usage.

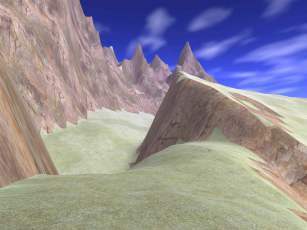

The earliest work on the Theed cliffs

I also recall that the lead graphics programmer wrestled for a while with the issue of how to do nice smooth blending between tiles. It would require a ton of blend maps and overdraw, because tiles were stamped down at every tile; you could in theory have one tile with eight different neighbors. He worked on trying to deal with it in a way that would provide decent performance for a few weeks. After a while I remember asking him why he didn’t just always stamp tile textures down in 2×2 blocks, so that you never had more than two tiles meeting. He got an angry look on his face, and tile blending worked the next day.

The other big issue from all this, of course, was that the server needed to know all the map info too. And our servers were really no great shakes. I mentioned in the Jedi post how we discovered that our servers were going to be less powerful than we had anticipated — there was some sort of budget savings from re-using old EQ servers, or something, so we ended up with Pentium III-600s as servers. But where a given player’s machine needed to calculate everything around to the horizon for just that one player, a server needed to know the terrain around every player and every AI, so that pathfinding routines could be run, collision checked, AIs could move about, etc. And the server sometimes couldn’t keep up. This is part of why the AI alert radius, and the combat radius, fell so dramatically during beta, and why shooting through the ground was occasionally possible. (It may also be why we never got full 3d collision, meaning that you couldn’t jump over tiny little walls).

Dynamic rules and the content it unlocked

One of the dozens of dynamic POI theaters I built

So, procedural terrain was kind of a big experiment, and it gave us a lot of headaches. Many of them were quite possibly game-impacting to a degree that was really damaging. In the meanwhile, Everquest 2 and Planetside were managing to move forward with their hand-crafted mesh solutions. But we stuck with it for another big reason. We could add rules on the fly.

Rules could be attached to any object in the world. And this unlocked the ability to place any building anywhere. We limited ourselves to simple circles, since they were the easiest to compute (distance from center). They would do a simple strong smoothing routine: clamp everything inside the circle to the elevation at the center of the circle. They’d have a little bit of a fade off at the edge of the circle. They might re-texture the terrain, and they’d have a no-rock-flora-or-other-crap set up.

The result was that we were able to do

player housing. Players were able to put down housing anywhere that wasn’t disallowed. Oh, we disallowed some of the wrong spots (for fiction reasons, we weren’t allowed to let people build suburbs around the core cities, even though those were the absolutely most obvious places to let suburban sprawl happen; as a result, we got fictional cities with a weird empty ring around them filled with newbie monsters, followed by an outer ring or “crust” of player city.

dynamic points of interest. These were encounters that spawned complete with some structures, rather than just spawning a monster. This let us in theory even have questlets spawn, which I have written about before. Dynamic POIs of this sort didn’t ever make it to launch, but spawning structures along with enemies certainly did. In general, spawning in SWG Wasn’t based on where in the world you were; it was based on where players already were, like random encounters in D&D. This was intended as an anti-camping mechanism, though it all too often resulted in spawns dumping a building on your head.

lairs. Rather than spawning single creatures, we generally spawned a creature spawner. The literal design spec was “like in Gauntlet.” Lairs spawned creatures up to a given population limit. Some of what they spawned were babies, intended for capture and taming by creature handlers. The others were adults, and “aggro” or attack-on-sight for peaceful creatures was driven by whether you were approaching their lair or not — everything defends its home, after all. Blow up the lair, and you actually killed the spawn. This concept started clear back in Ultima Online, where we spawned orc camps complete with orc wizards and whatnot. Unfortunately, as housing used up all the clearings in UO, these spawns eventually had nowhere to appear!

campsites. Players were able to build camps out in the wilderness that conferred much of the benefit of being in a town. Today, Galaxies players often remember camps as one of the most social features of the game.

military bases, which unlocked huge chunks of the Galactic Civil War for players.

military bases, which unlocked huge chunks of the Galactic Civil War for players.This unlocked an enormous amount of gameplay. You could spawn a little bandit camp on the side of a mountain, on a cliff even. It would create its own little ledge. When the camp was deleted later on, the rule would go with it, and the cliff would be restored to its original appearance.

Lastly, and perhaps most critically, this also unlocked the ability to do harvesting anywhere in the world, which was a crucial component of the game economy.

A size comparison between all of UO pre-Trammel, and SWG

In UO we had invisible resources attached to grass, to the rocks, to everything really. (see these three posts: 1, 2, 3). But all METAL was the same. There were no stats on METAL; originally, it was all steel-gray, even. One day I hacked in a system to that, which used (you guessed it) fixed random seeds to determine what kind of metal you got from a given location, and then I just attached a flag to the resultant ore. I checked for that flag at every step in the crafting process, and transferred the flag from the ingredient to the next stage. The result was colored armor of many different mineral types.

I knew we wanted this for SWG, and the best way to do it was to use an inheritance tree instead:

METAL

Ferrous

Iron

Non-Ferrous

Copper

…and so on. Designer Reece Thornton was assigned the system, and he went crazy with it, providing each resource with an array of statistics which could then be leveraged by the crafting system. We were able to swamp out the resources underneath the whole map, and allow players to build harvesters and factories anywhere at all, following the gold rushes and oil booms within the game. This then tied back into the crafting system, the game economy, and yes, the combat game itself, shaping the game very powerfully and helping to make it fell like a real world. The SWG economy and crafting system deserves its own post, but I did write about it here at a high level, in the midst of a post about something else.

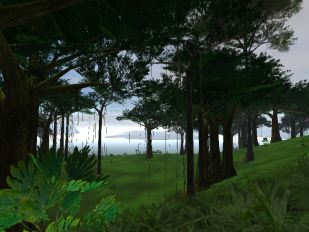

So in the end, a huge part of the “living world” quality of Galaxies came down to the idea that we shouldn’t necessarily know what was in our world. That it should be surprising us, as well as the players. Yeah, we had a lot of empty frontier land — it was supposed to have been thickly populated with handcrafted little encounters, cool locations, and so on, but we never managed that despite applying a small army of designers to it. But what it did offer: malleability and the unexpected — that turned out to be a key asset. It probably saved the production literally millions of dollars, for all the troubles it introduced, and might very well work even better on computers today, without all the issues that the system presented. Add in shadows, and butterflies, and procedural wind blowing things to and fro, and a day/night cycle where the stars actually moved across the sky, and pretty soon you were somewhere that while still low on framerate and blurred and choppy, could feel very immersive.

I used this picture as my desktop for years. I would be asked where the picture was taken, quite regularly. I think people expected to hear Arizona, and were taken aback when I instead said it was from a galaxy far, far away.

Earlier in this series:

A Jedi Saga

Temporary Enemy Flags in SWG

April 16, 2015

A Jedi Saga

Continuing here with the questions that were sent in by Jason Yates! Yesterday it was the TEF system… today it’s Jedi! Some of this stuff has been told before, but it’s actually kind of hard to find it all in one continuous tale. I have to preface this with a huge huge disclaimer, though: it’s been fifteen years since this particular story started, and a dozen since it ended. My memory may well be faulty on many details.

Continuing here with the questions that were sent in by Jason Yates! Yesterday it was the TEF system… today it’s Jedi! Some of this stuff has been told before, but it’s actually kind of hard to find it all in one continuous tale. I have to preface this with a huge huge disclaimer, though: it’s been fifteen years since this particular story started, and a dozen since it ended. My memory may well be faulty on many details.

#2 What were the thoughts on Jedi and why were such drastic changes made in patch 9 to the entire system?

-Jason Yates

Well, my opinion is Jedi are evil. Heh.

You see, Jedi are an immense attractant to players, readers, viewers. As a kid, I too waved around plastic lightsabers (we kept bending them as we struck one another, I am pretty sure my mom got really sick of buying new ones). Who can resist the fantasy of having this awesome sword, effectively magical powers — mind control, telekinesis, telepathy, and more — and of course, the classic Hero’s Journey? I mean, it’s basically an ideal play scenario.

Except that of course, you quickly realize that by comparison, everyone else sucks. I vividly remember granting Han Solo access to the Force when we played with the original action figures, because, well, he was too cool a character not to have them, you know? (We indicated Force powers by bending the legs all the way backwards, sort of a hip-shattering L shape, and then they could fly!) And let’s be honest, how long would Han Solo have lasted against Darth Vader? About two seconds. In fact, Kyle Katarn, the most popular Star Wars videogame character, basically is Han Solo with Force powers.

This is all fine and dandy in games where you play a Jedi and mow down Stormtroopers by the hundreds. It worked great in the Jedi Knight games. But Jedi are notably absent from the gameplay of other types of Star Wars games, and for a good reason. They are a discontinuity. They are too powerful. They are an alpha class. Not a problem is a single-player environment, but what do you do with them in a multiplayer setting where some people are badass Han Solo types who will always lose?

A Nightsister Witch of Dathomir

This same issue had come up in the Expanded Universe books and stories. You basically have the problem that

people identify with Jedi

they’re rare

they’re incredibly powerful

This meant that creators laboring in the universe had a few choices:

invent new stuff as powerful or more powerful as Jedi (which was done more than a few times — General Grievous, the Witches of Dathomir, the World Razer, a living planet called Zonarma Sekot, The Ones — OK, it was done a zillion times, which just proves my point).

tell stories with no Jedi in them, as in the original Han Solo books by Brian Daley. (Fun books, btw: The Han Solo Adventures: Han Solo at Stars’ End / Han Solo’s Revenge / Han Solo and the Lost Legacy )

Of course, the demands of games focused on Jedi also meant that the powers of Jedi kept having to go up, too! I mean, people actually complained when you didn’t start as a powerful Jedi in Jedi Knight II, and eventually, we got to the ludicrous heights of Starkiller in the Force Unleashed games: “sufficiently powerful enough to rip a million-ton Star Destroyer out of orbit and slap Darth Vader around like he owed him money.”

Early days

We weren’t the original Star Wars Galaxies team. There’s a complicated history there that there’s no point going into, but suffice it to say that there was a game design prior to the one that our team did. It was class based, used a “cone of fire” real-time action combat system, and I am pretty sure Jedi was one of the classes. There are a whole bunch of reasons why it went away in favor of our design, and I’m not going to go into them (I don’t even really think it was that team’s fault).

When our team got going on Star Wars, we didn’t have an office yet. We worked out of J. Allen Brack’s house (he went on to be incredibly important to the history of World of Warcraft); in fact, three of the team lived there. I distinctly remember having conversations with Chris Mayer in the living room of that house — probably between bouts of Soul Calibur, we were all hooked — and trying to figure out what the heck to do with Jedi. At this point, we didn’t yet have the game’s vision document, we didn’t yet have a game design, or anything. So the statement “live in the Star Wars Universe” was not yet our guiding star. But we knew already that having an alpha class in an MMO was going to be a real problem. The problem was clear:

Everyone wants to be a Jedi.

Jedi are rare during the original trilogy.

Jedi are super powerful.

Of these three pillars, something would have to give.

My first thought was, “make them NPC only.” After all, at the mandated time period in the films, there weren’t any around. If you read into the Expanded Universe, there’s all sorts of them in hiding, for the reasons given above. But evn all of those weren’t viable solutions for us. We were mandated to fall between the destruction of the Death Star and the Battle of Hoth. That’s a pretty narrow little sliver: the official timeline has it around 2 1/2 to three years. The number of of Force sensitives is small enough that Darth Vader is running around with a Death Squadron trying to find just the one who did the trench run. Allowing tens of thousands of players to be Jedi would surely be a bit jarring.

It also would have destroyed any semblance of grouping, much less the larger scale interdependence that we were already thinking about for the game. Given a choice between Jedi and, well, any other combat role, you’d pick Jedi. We’d probably have non-combatant types around… but maybe less of them, if everyone wanted to be a Jedi instead.

It also would have destroyed any semblance of grouping, much less the larger scale interdependence that we were already thinking about for the game. Given a choice between Jedi and, well, any other combat role, you’d pick Jedi. We’d probably have non-combatant types around… but maybe less of them, if everyone wanted to be a Jedi instead.

I think the general reaction even among the team, though, was horror. “A Star Wars game and you can’t be a Jedi??”

The second thought was, “make them not powerful.” This was in fact the approach that original design had taken, and pretty much what happened after the NGE as well. As one class out of several, Jedi simply don’t have the powers they do in the films. Oh, they look like they do, but in practice their force lightning is just a blaster bolt and they are balanced to match the other classes. No Starkiller here.

The problem here, of course, is that the fantasy is shattered. Not only would there be Jedi all over the place, but they wouldn’t be special on any axis. And in this time period, Jedi were special. Oh, we’d had seen them be rather non-special, in The Phantom Menace; the film came out the year before this early development phase, and in it we saw Jedi as more like government diplomats, on the level of a trade attache or something. (We also learned that it was because they had won a genetic lottery, but that’s beside the point).

But the idea of Jedi as rare and powerful was pretty ingrained. So the idea of making them common and not that special didn’t sit well at all.

There was a third option that came up, and I pitched it to LucasArts in a casual conversation with Haden Blackman, who was our producer there (today he’s known for some pretty kick-ass comics writing). It survived about thirty seconds.

“Just change the time period,” I said. This would have allowed us to have way more Jedi, because in the Expanded Universe we have a Jedi Academy during this time period. It would have cost us Darth Vader and Palpatine, Jabba the Hutt and… well, not that much else. Even Boba Fett climbed out of the Sarlaac. The Empire was still quite strong, according to the Timothy Zahn books

“Just change the time period,” I said. This would have allowed us to have way more Jedi, because in the Expanded Universe we have a Jedi Academy during this time period. It would have cost us Darth Vader and Palpatine, Jabba the Hutt and… well, not that much else. Even Boba Fett climbed out of the Sarlaac. The Empire was still quite strong, according to the Timothy Zahn books ; we had all sorts of new enemies popping up, and there was even a good reason why new Jedi might be weaker than those in the past, given that there were literally no trained Jedi Masters who could teach them.

; we had all sorts of new enemies popping up, and there was even a good reason why new Jedi might be weaker than those in the past, given that there were literally no trained Jedi Masters who could teach them.

There were probably a pile of logistical reasons why this couldn’t happen. I shudder to think of the approval process that might have been required, especially to go back and amend an existing deal. The fact that the game development process was being rebooted was a touchy subject in itself; early chats with Haden were marked by a lot of “and what about X, is that staying?” All in all, even though it was probably the cleanest solution, it never had a chance for reasons that had little to do with game design.

So, that left us at the three pillars, intact. Powerful, rare, and in the hands of players. We were screwed.

The crazy idea I still wish we had done

I had a brainfart that never made it past those early days, there in that house. The idea took inspiration from Hardcore mode in the Diablo games. We would offer a Jedi system that effectively gave a different way to play the game. A method that kept Jedi rare, powerful, and yet allowed everyone a shot.

I had a brainfart that never made it past those early days, there in that house. The idea took inspiration from Hardcore mode in the Diablo games. We would offer a Jedi system that effectively gave a different way to play the game. A method that kept Jedi rare, powerful, and yet allowed everyone a shot.

Every player would have a special character slot available to them, distinct and parallel from their regular character. This character would be locked into one profession, one class: Jedi. They’d start out weak as a kitten though, untrained in combat or anything, and with barely any Force abilities at all. Luke without womprat-shooting experience maybe.

Although the design wasn’t done yet, we knew that the game would be classless. So this pathetic Force Sensitive character would be able to gain better Force powers by earning Force XP by using the Force. They could also go off and learn other skills. But either way: if they died, that was it. They were dead. Reroll. Start over. It was that dreaded word: permadeath.

In the corner of the screen, there would be a timer running logging how long you had managed to survive. It was your score, for this weird little minigame. The name of the game was survival, but it was rigged.

You see, the moment you used Force powers within view of anything or anyone Imperial, or indeed any player, they could report you to the Empire. To Darth Vader’s Death Squadron in fact. And that generated someone to come after you. After first, just lowly Stormtroopers. Eventually, cooler characters, such as some of the bounty hunters like IG-88. Eventually, really cool ones like Boba Fett or fan favorite Mara Jade.

These would be brutal fights. Odds are you’d just die. So hiding and training very carefully would be essential. But it wouldn’t matter, of course. As you advanced, your powers would get “noisier” and cooler. You wouldn’t be able to resist using Force Lightning in a crowd, or equipping your lightsaber in view of some Imperials. And eventually, after Boba Fett and Mara Jade and everyone else had failed, well, that would be when Darth Vader himself bestirred himself to take care of the little problem.

These would be brutal fights. Odds are you’d just die. So hiding and training very carefully would be essential. But it wouldn’t matter, of course. As you advanced, your powers would get “noisier” and cooler. You wouldn’t be able to resist using Force Lightning in a crowd, or equipping your lightsaber in view of some Imperials. And eventually, after Boba Fett and Mara Jade and everyone else had failed, well, that would be when Darth Vader himself bestirred himself to take care of the little problem.

And you would die. It would be rigged.

Your time would go up on a leaderboard, and everyone would be able to ooh and aah over the hardcore permadeath player who managed to get all the way to seeing Darth Vader and getting her ass kicked.

As a reward, if you managed to make it to Jedi Master, your very last skill would be “Blue Glowy.” You’d unlock a special emote for your main character slot that allowed them to summon up the ghosts of every Jedi who had made it that far. So all the bragging rights would carry over to your other character. Heck, I had a picture in my mind of the most amazing player summoning up not one, but a whole set of them — the most badass player would have a coterie of Jedi advisors, hovering around their campfire, as they showed up.

The response to this idea was pretty much “Permadeath?!?” And so Hardcore mode never happened.

The actual design

Now we hadn’t managed to remove a pillar, we’d added one. Not a step forward.

I am pretty sure it was in conversations with Chris Mayer (our lead server programmer) that we hit on the notion of making the process of becoming a Jedi effectively a personality test. As I recall, the question was around “if we’re going to have all these Jedi around, and need to keep them rare but acting like they do in the movies, that almost calls for a roleplayer only profession, or some other way to make sure that only those who actually deserve to be Jedi become one.” See, we knew that Jedi would be the top target above all for the Achiever and worse, the Killer types, in Bartle lingo. It was too attractive a target, and if we made the way of becoming Jedi involve quests, or grinding points in some fashion, it would inevitably go to the powerhungry. But really, we wanted a system that was more for the Explorer type: someone who savored the game.

I am pretty sure it was in conversations with Chris Mayer (our lead server programmer) that we hit on the notion of making the process of becoming a Jedi effectively a personality test. As I recall, the question was around “if we’re going to have all these Jedi around, and need to keep them rare but acting like they do in the movies, that almost calls for a roleplayer only profession, or some other way to make sure that only those who actually deserve to be Jedi become one.” See, we knew that Jedi would be the top target above all for the Achiever and worse, the Killer types, in Bartle lingo. It was too attractive a target, and if we made the way of becoming Jedi involve quests, or grinding points in some fashion, it would inevitably go to the powerhungry. But really, we wanted a system that was more for the Explorer type: someone who savored the game.

This meant we couldn’t do something with a standard quest. Too susceptible to the issues with static game data in large communities. Any solutions would get shared, and the rarity would fall by the wayside.

I pulled out a very old idea, so old it was from the MUD-Dev days, about a spellcasting system that used spell words, but the words were different for every player (didn’t Asheron’s Call end up doing something of the sort?). That way recipes couldn’t be shared, but just the broad idea could. That seemed like it had some promise. So we started thinking of tasks or quests that players could do that could vary by player. And I am pretty sure it was Chris who said “what if the tasks were from different Bartle types?”

And so we landed on the system:

There would be a large pool of possible actions a character could undertake, divided into four categories, one for each Bartle type.

These actions would include things like “visiting the highest location on a given planet,” “using this specific emote,” “killed this particular creature,” “learned this skill,” “did five duels,” “entered this battlefield,” “crafted this item,” etc. Some of the exploratory ideas were taken from Seven Cities of Gold, and others from badges we expected to give, and so on. (Remember, achievements didn’t exist yet. The idea was almost certainly copied from online games).

Every player would randomly roll up a different set of actions they needed to undertake. Their personal list would include some items from each of the four categories so that it was always balanced across playstyles.

The player would not be told that they had checked off an item.

The player would not be told that they had checked off an item.The player would not be told that they had checked off all the items, either — they would be notified of Jedi status the next time they logged in.

We wouldn’t tell even the development team how exactly it worked. Most of them didn’t know.

Yes, it was absolutely security through obscurity, which is exactly what security people tell you not to do. But it had some great advantages.

Nobody would know how to become a Jedi, so all those obsessive grinders and walkthrough readers wouldn’t be able to do it by rote. And yet we could tell everyone with utter honesty that anyone could become a Jedi.

It would be pretty rare. A player who actually engaged in all the different aspects of the game, who moved across playstyles that freely, would be highly unusual.

We could keep Jedi superpowerful, since they were so rare. Odds were that any player who had done that breadth of things was already maxed out in power anyway.

Given the level of investment required at that point, permadeath seemed like it didn’t fit, so that went away.

At that point, all that would need to happen would be implement a truly expensive set of custom animations and skills. So, we made the plan, a doc was specced out that included the list of possible tasks, and there it sat until we got to it on the schedule.

We’re out of time

We never got to it on the schedule. SWG’s development was hurried. The whole game was made between September of 2000 and June of 2003, which is an insanely abbreviated development time. For comparison, World of Warcraft was announced in 2001 and launched after probably five years of development. In SWG’s case, sure, there had been a bunch of time invested in the game with the earlier team, but there was virtually nothing we were using. Effectively, we had started over from scratch. The originally announced availability date was in 2001, which was already impossible. As a result, we were already insanely behind by the time we hit the alpha date. It was September of 2002 or thereabouts and so little was working that we did what eventually turned out to be an incredibly valuable testing process: we inveted only 150 people in, and we focus tested each feature as it was ready.

We never got to it on the schedule. SWG’s development was hurried. The whole game was made between September of 2000 and June of 2003, which is an insanely abbreviated development time. For comparison, World of Warcraft was announced in 2001 and launched after probably five years of development. In SWG’s case, sure, there had been a bunch of time invested in the game with the earlier team, but there was virtually nothing we were using. Effectively, we had started over from scratch. The originally announced availability date was in 2001, which was already impossible. As a result, we were already insanely behind by the time we hit the alpha date. It was September of 2002 or thereabouts and so little was working that we did what eventually turned out to be an incredibly valuable testing process: we inveted only 150 people in, and we focus tested each feature as it was ready.

Yeah, that means we tested chat for the first time in September of 2002. And launched less than a year later. Combat came online in November or something. And content tools came online… never.

Well, no, not never. Just hardly ever, if that makes sense. SWG hit its “code complete” drop dead date around February. What you think of as “the game” was mostly built between August and February. We had building tools and the like, and we had a rich set of game systems, because sandbox and simulation-heavy games can be made much much faster and more cheaply than content-heavy games. But adding the required content to the game starting in February, to finish in May? Just not possible.

We had to go through and make tough choices on cuts. As early as that Christmas I was already triaging the entire game design. My criteria was “can the game function without this.” Not “will it be good.” Will it work at all. This led to often weird priorities based on the fact that the game relied a lot on player interdependence. You could probably have postponed Image Designer (the profession that involved one player changing another’s appearance). But it was actually our first scripting test because it was so tiny, and so it made the cut because it got done way early and took so little effort. You could push off player cities because no players would be advanced enough to make one. You could always walk, if there weren’t vehicles. It would suck — the planets had been planned assuming landspeeders! But you could get there. But we couldn’t change out, say, dancing, because the healing of battle fatigue was a critical portion of the game loop. (Spaceflight was never intended to be in the initial launch — we knew on day one that was out of reach).

I watched so many features fall apart during this period.

All those characters, so little dialogue.

Game scripting was in Java, and where I had hoped our designers would be able to script cool intricate quests, or even build us a quest system, we got rather iffy content that seemed to break constantly even though the designers tried hard. We had to resort to mission terminals, which were just one of many types of content that were supposed to be present, as our main content activity. I had dreamed of a Jabba’s Palace where every single character had the full backstories from the books, and you could do quests for all of them. We didn’t have a template-style quest system working; at one point Scott Hartsman came out to do a sanity check of our development, and I suspect he found me rather full of despair, as every item he enumerated should be there for content development was absent. This meant we sure as heck weren’t going to manage to get the player contract system whereby you could be given a quest by another player. Dynamic POIs were worked on for a month or two, then basically abandoned because of terrain engine issues and scripting difficulty.

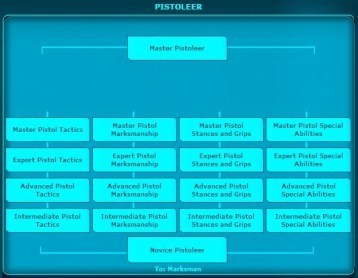

Professions fell out. The designer who was doing the skill trees couldn’t manage to lick the problem of trees that were of varying sizes and interconnected in unique ways; originally, the trees were all different, and there were “surprise” professions that might appear if you mastered two skills from disparate professions, more like a skill web. Said designer left the company for another job elsewhere, and the producer made a command decision, created the skill onions, and we had to do those. This meant that professions that were meant to be tiny, like Image Design, had to bloat out to fit a rigid structure, which actually increased their scope. Other professions that could have had many more skills or skill lines in them had to conform to the rigid four-track onions. Some were cut altogether, including my beloved Writer profession, and Miner, and some others.

We learned during beta that our deployment hardware was going to be less powerful than we had expected. As a result, we couldn’t compute the really nifty procedural terrain on the servers as far out as we had hoped. As a result, our range for combat fell in half or more. This actually broke everything, because the new range was smaller than the minimum optimum range for rifles and snipers. Creatures couldn’t pathfind, suddenly. In alpha testing, our AI was way smarter than it was at launch. Pathfinding was supposed to include things like creature emotional state affecting the paths they chose — e.g., you could stampede a scared critter right off a cliff, and different creatures would attempt different slopes based on how scared they were. Instead, even the basics of whether they were scared of you or not started to not work well. Dynamic spawns that affected terrain couldn’t adequately check to see if anyone was there, so buildings would spawn on top of someone else. I don’t remember exactly when we realized we had to settle for 2d collision instead of 3d, which meant you couldn’t step over a short wall, but that made nobody happy, and I had to defend it on the forums.

We learned during beta that our deployment hardware was going to be less powerful than we had expected. As a result, we couldn’t compute the really nifty procedural terrain on the servers as far out as we had hoped. As a result, our range for combat fell in half or more. This actually broke everything, because the new range was smaller than the minimum optimum range for rifles and snipers. Creatures couldn’t pathfind, suddenly. In alpha testing, our AI was way smarter than it was at launch. Pathfinding was supposed to include things like creature emotional state affecting the paths they chose — e.g., you could stampede a scared critter right off a cliff, and different creatures would attempt different slopes based on how scared they were. Instead, even the basics of whether they were scared of you or not started to not work well. Dynamic spawns that affected terrain couldn’t adequately check to see if anyone was there, so buildings would spawn on top of someone else. I don’t remember exactly when we realized we had to settle for 2d collision instead of 3d, which meant you couldn’t step over a short wall, but that made nobody happy, and I had to defend it on the forums.

Databases were clearly going to be a huge issue, thanks to the crafting system, which had turned out awesome but also considerably more detailed than specced. A large pile of unique stats needed to be tracked on everything. Space was at a premium; character records were enormous. This caused problems when players moved between physical servers or across server processes, because of the time required to copy the data and the race conditions that could emerge.

We were sent a literal army: dozens of QA and CS people were bused in from San Diego to desperately try to build out all the planets. They had to learn the tools and build little points of interest. We were desperately short on managers; Cinco Barnes, who had been just leading the content team, had to manage everyone on the design team — dozens and dozens of people — while the producers and I basically took on the job of hotspot firefighters, going from problem to problem to problem to fix them as efficiently as we could.

Oof, these paragraphs felt like opening a vein. SWG fans, you have no idea what the game was supposed to be like, and how weird it feels to hear adoration for features which to me ended up being shadows of their intent. Don’t get me wrong, the team did heroic, amazing work. All of these issues end up being my fault for overscoping or mismanaging, the producers fault for not reining me in, or the money people’s fault for not providing enough time and budget. The miracle is that we pulled it off at all.

You can see where this is going. There we are, out of time. And there’s this big looming must-have system that is really, quite complex, adds a ton more tracking, and which we just didn’t have time for. Oh, we could push implementation of some of it to post-launch; after all, Jedi were going to be rare, so we had months before any Jedi Masters demanded that their Force Lightning actually, you know, work. But we couldn’t push off the tracking, because that was what the core was: whether you could actually start working on being a Jedi. We’d be lying about Jedi being in the game at all if at least that piece wasn’t there.

Chris or J comes to my office one day. I don’t remember what I was doing exactly, and I don’t remember who it was exactly. Re-speccing PvP, possibly, or trying to get decent data so I could see if combat was balanced (which it wasn’t, and never was). He tells me, “We can’t do it. We can’t gather and track the data. We don’t have the time to do it. We need a new system.”

Chris or J comes to my office one day. I don’t remember what I was doing exactly, and I don’t remember who it was exactly. Re-speccing PvP, possibly, or trying to get decent data so I could see if combat was balanced (which it wasn’t, and never was). He tells me, “We can’t do it. We can’t gather and track the data. We don’t have the time to do it. We need a new system.”

My brain fuzzes out. “It took weeks to figure out any solution at all. We can’t do a content solution, we have no time and no tools.”

“It’s OK, there’s an idea. We can’t track all of that, we there are some things we are already tracking. Skills. They cover all the different personalities, all the Bartle types. We have socializers and we have explorer skills with surveying and we have combat stuff all over the place… So I am here to ask you, can we just make the randomized list be a set of skills.”

I had twelve other things to do. I said yes, and on we went.

It was a fateful decision.

A Jedi by Christmas

The game launched, barely. It was in such bad shape that we knew we were going to announce its launch to the beta testers and they would crucify us, because they could see perfectly well that the game was not ready. We flew out the top commenters on the forums and told them. Their faces fell. They were beyond dismayed. We threw ourselves on their mercy and asked for their help. Not to lie, but just to tell their fellow players that we were doing everything we could to get the game into decent shape. It was true; we were. We had managed to get a couple extra months from management — not the six months or a year I had hoped for. Everyone was basically living at the office. We had been so open and honest and communicative with the playerbase on the forums that when we asked for the playerbase’s goodwill, we actually got it. (Our community management actually became a case study for how to build collaborative environments with fans that was written about in Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide

The game launched, barely. It was in such bad shape that we knew we were going to announce its launch to the beta testers and they would crucify us, because they could see perfectly well that the game was not ready. We flew out the top commenters on the forums and told them. Their faces fell. They were beyond dismayed. We threw ourselves on their mercy and asked for their help. Not to lie, but just to tell their fellow players that we were doing everything we could to get the game into decent shape. It was true; we were. We had managed to get a couple extra months from management — not the six months or a year I had hoped for. Everyone was basically living at the office. We had been so open and honest and communicative with the playerbase on the forums that when we asked for the playerbase’s goodwill, we actually got it. (Our community management actually became a case study for how to build collaborative environments with fans that was written about in Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide . I am very proud of what we accomplished there). People were upset, but there was a sense that we were all in it together. Our day one sales of the game were a one-to-one exact match for the registered forum population.

. I am very proud of what we accomplished there). People were upset, but there was a sense that we were all in it together. Our day one sales of the game were a one-to-one exact match for the registered forum population.

And then when the game launched, it didn’t actually work. Like, you couldn’t log in. But gradually, we recovered, and started working on the missing features, and did in fact deliver them over the course of the next six months. But many of the cuts had been irreversible, many of the changes permanent. Jedi work continued as the skills were developed, but combat was dramatically out of whack, there was a duping bug to try to find, player housing was getting placed around the entrances to the very few pieces of static content we had and people were effectively claiming dunegons as private property. All sorts of stuff was a mess.

This was the glorious “pre-CU period” that today people recall so fondly.

And I had been offered the role of Chief Creative Officer, in San Diego, before the game had even shipped. I had taken the role, but had stayed working on SWG to try to get it into good shape before I left — I was going to have to move. Gradually I had to give up more and more ownership over the game, and there were parts of things that simply vanished in the handoff — probably the most critical of these were metrics around gameplay balance and the economy.

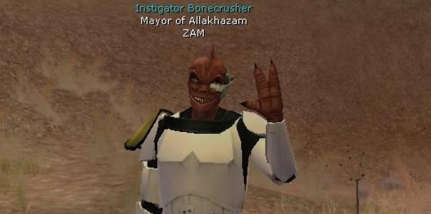

This was a player city.

But the game was shaping up. Players had formed governments. Vehicles were very popular. The early game economy, which was intentionally rocky becuse players had not yet developed all the interdependence infrastructure, had started to hum along. Entertainers were going on tour, and few of them were macroing, because they played entertainers because they liked it. People were building supply chain empires and businesses with hundreds of employees. Merchants were making a name for their shops full of custom-crafted gear.

And most importantly, nobody was a Jedi. Nobody cared. They were playing the professions they liked. They were doing what they wanted to do. The secret of Jedi was a secret still, and there were countless theories. Players thought they were being watched and only the deserving would be picked. Players thought that various half-finished bits of content were actually the star tof Jedi quest chains. And meanwhile, players were invisibly checking off items on their secret skill lists.

And LucasArts marketing says, “we need a Jedi by Christmas.” The rocky launch and general bugginess had cost us a huge number of subscribers. Oh, we were still the second biggest MMO outside of Asia, behind EverQuest, but the expectations were much higher. Many players had simply churned out, unwilling to deal with the general jankiness. But the game was improving by leaps and bounds, and marketing wanted to get a fresh flow of users in now that the game was actually working.

And LucasArts marketing says, “we need a Jedi by Christmas.” The rocky launch and general bugginess had cost us a huge number of subscribers. Oh, we were still the second biggest MMO outside of Asia, behind EverQuest, but the expectations were much higher. Many players had simply churned out, unwilling to deal with the general jankiness. But the game was improving by leaps and bounds, and marketing wanted to get a fresh flow of users in now that the game was actually working.

We looked at the rate at which people were unlocking their skill boxes, and did a back of the envelope calculation. It showed that the first Jedi might manifest in… 2012 or so. Marketing was not amused. “Drop hints,” the team was told.

I was already half off the team, commuting between Austin and San Diego every week or two. (I would eventually move at the end of the year). But I am pretty sure I was in at least some of the meetings. The decision was made to drop Holocrons, hint boxes that would tell you one of the skills you needed to learn.

The problem is obvious: as soon as three people all have gotten a hint that what they need is to master a specific skill box, the secret was out. It was weak cryptography. As the confirming data poured in that none of the Holocrons involved anything other than skills, the players set themselves with a will to trying to crack their personal codes. And they used the oldest trick in the book: brute force.

They simply started at A and learned every skill. In order. Probability being what it was, most finished when they got partway through. But the problem was this meant playing what you didn’t like.

The peaceful dancers who thrived on joking around with an audience and doing coordinated flourishes found themselves tramping around the mud looking for mineral deposits.

Obtainable. Powerful. Rare?

The explorers who enjoyed exploring distant swamps got themselves trapped in medical centers, buffing an endless line of combatants.

The doctors who derived their pleasure from helping out people in a support role found themselves learning martial arts or machine guns and mowing down creatures.

The combat specialists who were used to optimizing damage per second in taking down a krayt dragon were instead raising them from babies.

The creature handlers who tended dewbacks had to learn to chop them up and cook them instead.

You get the idea. Everyone started playing everything they didn’t like. Oh, some players discovered new experiences they never would have otherwise. Many emerged from this with a new understanding of the fundamental interconnectedness of a society. But most just macroed their way or grinded their way through it all as fast as possible, dazzled by the booby prize of Jedi.

Satisfaction fell off a cliff. I never did see a marketing push for Jedi — never saw a marketing push for the game at all, to tell the truth. But what I do know is that one month after Holocron drops began, we started losing subs, instead of gaining them. SWG had been growing month on month until then. After Holocrons, the game was dead; it was just that nobody knew it yet.

My handle on the forums had been Holocron.

And later…

Pretty much every single subsequent change can be traced back to that day. All the panicky patches, the changes, the CU and the NGE, were all about trying to get the sub curve back on a growth trajectory. Some of them were good changes. Most of them were bad, in my opinion. But they can all be traced to me saying “yeah, fine, skills is good enough” in a hurried minute-long conversation on a work day that was probably fourteen hours long.

Pretty much every single subsequent change can be traced back to that day. All the panicky patches, the changes, the CU and the NGE, were all about trying to get the sub curve back on a growth trajectory. Some of them were good changes. Most of them were bad, in my opinion. But they can all be traced to me saying “yeah, fine, skills is good enough” in a hurried minute-long conversation on a work day that was probably fourteen hours long.

Nobody much liked Holocrons as a Jedi mechanism, of course, and the playerbase felt betrayed. It seemed like a cruelly mechanistic trick, after the dreams they had had; a system that worked better when nobody knew how it worked. And it had worked, for a while. People dreamed of Jedi, and were content, and had fun. They were attainable, powerful, and absent, and the rat race wasn’t a factor.

Eventually, the team tried new things. They did a quest chain instead, the Jedi Village. To be honest, I never played it, and I was not only off SWG but very out of the loop by the time it went in. The genie was out of the bottle, though: Jedi was a thing for grinders and achievement-mad powergamers, and a little quest chain was never going to stop them. They were everywhere.

By the time of the NGE, they were a class to choose, as they had been in the original design we scrapped. Not very special. Not very powerful.

I never even logged into the game after NGE, to be honest.

Holocron was my last handle, on any forum. And I never played a Jedi at all.

April 15, 2015

Star Wars Galaxies Temporary Enemy Flagging

I was sent this list of Star Wars: Galaxies questions by Jason Yates; he had seen this video interview, and didn’t know enough Spanish to be able to follow the answers. I posted up an English translation of the transcript here, but really, the interview didn’t much overlap with the questions he had.

I was sent this list of Star Wars: Galaxies questions by Jason Yates; he had seen this video interview, and didn’t know enough Spanish to be able to follow the answers. I posted up an English translation of the transcript here, but really, the interview didn’t much overlap with the questions he had.

Is there the possibility of you ever giving a question/answer session in relation to SWG, your views on the game development and direction, aspects of the game you felt worked, worked well, didn’t work at all? Like many, I have so many questions about your involvement with SWG and will likely never get all the answers I would enjoy hearing, but it never hurts to ask. ^_^

Well, honestly, for me it has been fifteen years since I started work on SWG, and twelve since I stopped. So a lot of these questions have either been answered before, or I outright don’t know or remember the answers! So I will give it a try. But the first answer turned out to be so damn long that it’s all I have time for today.

The TEF system and how it was thought up and designed.

TEF stands for Temporary Enemy Flagging. We knew when doing a Star Wars game that we needed to be able to account for the scenarios in the movies. This makes for a tricky problem: after all, we saw Luke clearly pick sides, Han only sort of do so at first, both of them ended up wearing Stormtrooper armor to hide, someone like Lando actually switched sides kinda, and all sorts of other ambiguous situations that don’t lend themselves well to a straightforward system where you declared for one side or the other at the start and were done.

On top of that, we knew that PvP was, well, fatiguing. Given that we were limiting each account to having a single character (for lots of reasons, including PvP, actually), making players have to pick a side, never change, and be always vulnerable, felt like a big ask. The spirit of the game was all about changing your character up over time, and trying new things, so a system of permanent choice for PvP felt wrong.

Lastly, something that I think people have forgotten, in these days of DayZ, Rust, and H1Z1, is how much there was a general aversion to PvP. Ultima Online had had a big issue with playerkillers marauding around, and had famously cloned the map and simply made a non-PvP “dimension.” EverQuest was philosophically opposed to it — it was a feature, but really barely present in terms of the game consciousness.

When we were sharing design thoughts on SWG (something which we did extensively, to a degree that even games today rarely do), I posted up a very clear statement on the forums that runaway PKing was simply not going to be a feature of Galaxies.

I still believe many things. I still believe that we can find ways to allow players to police their environment. I still believe that this can open up the way to many extremely cool features new to these sorts of games. And I am continuing to work towards having these many features: real battles of territory. Player governments with actual importance and consequence. Player communities that are refined and defined via conflict and struggle so that their battles MEAN something. Real emotions–yes, even including fear and shame, because this is a medium like any other art medium, and its expressive (and impositional!) power is amazing and worthy of exploration. I believe that virtually every player can try PvP and enjoy it, if it is designed correctly, and that it adds great richness to the online gaming experience.

But I do not want to ever disappoint people in that way again. People will come to SWG for those things, and I do not want them to discover that they cannot stay and enjoy them because the very freedoms which allow those cool, innovative, exciting features, also allow d00dspeaking giggly jerks to dance roughshod jigs on their virtual corpses.

So am I willing to make compromises in “realism” (a radically overvalued thing in game design, frankly) to make sure that SWG remains someplace where most everybody can feel welcome?

You betcha.

Some antecedents

In Ultima Online we had tried a number of systems to deal with open player versus player combat while still providing safety. All of them were systems based on the idea of “you can attack, but you’ll get flagged somehow as a result.” This is as opposed to what were commonly termed “PK switch” systems, where you flipped a flag on yourself in advance, and could only fight other players who had also made that choice. The general consensus, I think, is that blocking in advance was better for the peaceful player; no punishments for flagging ever seemed to really deter a playerkiller. The third major system in use was realm versus realm combat, best exemplified by Dark Age of Camelot — basically, dividing the map into territory in advance, and saying you were always safe from your side, but the sides simply didn’t interact except at the boundaries. When they did interact, they weren’t even allowed to communicate, in order to minimize channels for griefing.

The original proposal for a PvP system in SWG was actually something called Outcasting. It was based on the idea that players were going to own pieces of territory in the world, and be able to set laws within that territory. The key to the system was the idea that players basically all had a “license to kill,” but it could be taken away, almost like inverting the traditional PK switch. If you committed a murder in a territory, the decision on whether to take away your ability to PK fell to the leadership in the territory. Any PK incident would automatically send a log of the events to the local government, so they could make a decision. This would allow a player government to always forgive their “police force,” for example. Or to allow a PK incident if it was well roleplayed, etc. Removal of the ability to PK would then be tied to that territory. Go into no man’s land, and you could still kill anyone.

The original proposal for a PvP system in SWG was actually something called Outcasting. It was based on the idea that players were going to own pieces of territory in the world, and be able to set laws within that territory. The key to the system was the idea that players basically all had a “license to kill,” but it could be taken away, almost like inverting the traditional PK switch. If you committed a murder in a territory, the decision on whether to take away your ability to PK fell to the leadership in the territory. Any PK incident would automatically send a log of the events to the local government, so they could make a decision. This would allow a player government to always forgive their “police force,” for example. Or to allow a PK incident if it was well roleplayed, etc. Removal of the ability to PK would then be tied to that territory. Go into no man’s land, and you could still kill anyone.

Some of this was inspired by how the late Jeff Freeman had run his UO gray shard — in that game, as you killed citizens of one town or another, you became an instakill target in that town. So going on a crime spree meant that eventually, you’d be denied all the basic services and more or less be unable to play, obliged to live “out in the woods” as an outlaw.

I don’t remember exactly why this didn’t get implemented. We talked about it some on the forums and in dev chats. But it wasn’t all that Star Warsy, clearly, and depended heavily on a territory system that was inevitably going to slip out of the initial release. It was set up much more around player towns than around Rebellion and Empire factions. It had challenges around the logging, related to privacy issues and storage. All in all, it was a bit of a pain.

The birth of TEFs

So it was abandoned in favor of a new system, what came to be known as Temporary Enemy Flags, which I ended up designing myself relatively late in the development cycle. The main goal, as I mentioned, was to try to mimic the events in the movies as much as possible. But artificial stuff like grouping and housing rules and the like quickly got in the way.

Basically, what I did was try to take scenarios from the movies and come up with a ruleset that would allow them to happen in the game. But of course, the game offered far more scenarios than the movies did!

The core of the system was these ideas:

that a lot of players would probably like to join the Rebels or the Empire without being forced into PvP. This part turned out to be completely true.

that many players might well like to jump into PvP temporarily, as long as it wasn’t a permanent commitment. This also turned out to be correct.

that players would find it really confusing and non-Star Warsy if you were an Imperial and saw players killing NPC Stormtroopers willy nilly and couldn’t do anything about it. This, it turned out, was not really the case. We were pursuing Star Warsy fictional consistency with this bullet point, basically, and it turned out to be an aspect where eventually gamey-ness won out.

Basically, you started out as a civilian. Either side would leave you alone, but you had to opt out of attacking NPCs from either side, too. So no fighting Stormtroopers or Rebels.

You could go sign up as a covert member of a side. This meant you were secretly on that side, but it didn’t really show. So if you were a covert Rebel, Stormtroopers wouldn’t kill you on sight. But if you attacked one, then you were visibly a Rebel for something like fifteen minutes after the last blow or shot because we applied a temporary enemy flag to you. After that, you were safe again. But in the meantime, you were completely vulnerable to the other side — which included players from the other side.

Lastly, you could be overt, which meant you were visibly on a side at all times — basically, this was like a PK switch being flipped. This meant you could be attacked by the other side at any moment, whether it was by NPCs or other players. But it also meant you could use all sorts of cool perks since you were effectively “in the army.” You could wear Stormtrooper armor, you could command an AT-ST, call in an airstrike even. There was a whole ladder of worth of faction perks, up to the ability to build entire bases with laser cannons and everything so you could try to re-enact the Battle of Hoth. Coverts had more limited access to this stuff — I think they were only usable when you were flagged? Or maybe using them flagged you. I don’t remember.

You could drop back from Overt to Covert again, with some effort and loss of capabilities. You could even drop out of Covert and go back to being a civilian, and then switch sides.

All that seems pretty straightforward. But that’s not where the problems arose.

What the heck is a helpful action?

The problem is, what’s the list of stuff that can trigger the flag? Attacking a Stormtrooper seems like an obvious candidate. But what about healing a Stormtrooper? What about handing fresh ammo to a Stormtropper who is almost out? What about inviting that Stormtrooper to hide inside your house while denying a Rebel entry?

Worse, some of the things you could do as a helpful action were even sort of passive. If you were an entertainer in a bar, and someone chose to watch you, you were healing them of battle fatigue. You couldn’t say no… do you get flagged, because you are now helping an Imperial?

Worse, some of the things you could do as a helpful action were even sort of passive. If you were an entertainer in a bar, and someone chose to watch you, you were healing them of battle fatigue. You couldn’t say no… do you get flagged, because you are now helping an Imperial?

The many tentacles of “helpful activity” quickly made the ruleset a morass of edge cases. We had to account for bounty hunters, for example. We had to worry about the case where you were grouped with someone who performed a helpful action on someone. What if the group was mixed coverts from both sides, and then one of them went overt? Should they suddenly be vulnerable to their own group members, or is the group bond sacrosanct? What about bounty hunters, who effectively had an orthogonal PvP system layered on top?

These things quickly turned what had been a fairly clean system into a nightmare.

The thing is, the system did do a good job of capturing the Star Warsy moments. I was able to walk through the entirety of Episode IV’s plot with the TEF system, and literally every example worked (except that I think we didn’t allow Rebels to secretly wear Stormtrooper armor). Even well after the system was removed there were plenty of people who felt that it never should have gone away. People who favored it enjoyed the fact that sudden battles could erupt out of nowhere, that you could have that tension of committing a sudden attack, becoming vulnerable, and the adrenaline rush of trying to stay alive until the timer expired. It brought that rush of free-for-all into the game in a way that was temporary.

Ultimately, SWG’s pre-NGE PvP was a customizable system that catered to everyone. Well, everyone except griefers, basically, because unless you remained willfully ignorant of the mechanics and made mistakes with your flagging, it was impossible to be griefed even though you were playing a game that featured open-world FFA PvP. It wasn’t a perfect system, though. For my money, there could’ve been some harsher consequences for aggressors. There were no real penalties for instigating a fight, and basically the only punishment for dying — aside from gear decay — was a set of temporary debuffs and a timer that made you wait a few minutes before re-engaging.

— http://www.engadget.com/2014/01/17/some-assembly-required-pre-nge-swgs-proper-sandbox-pvp/

On the other hand, “making mistakes with your flagging” as this quote puts it, happened all the time. Saying it was “impossible to be griefed” is just not correct. To quote one player who was on the receiving end of it far too often,

TEF, in itself, is not all that bad of a system but it’s what players do with it. Greifing seems to be the norm and quite looked forward to via a very small group of some players. And that very small group can easily ruin gameplay for almost everyone else. Imagine a group of 20 rebs sitting outside the Emp’s Retreat waiting for some unsuspecting new player to try and get a mission returned. Or another group of imps doing the same outside Coro, Lok, Dant, of Yavin. The themeparks would be unused and un-doable content, pure and simple. The same could be said for the load in areas from the vette along with many other instances of regular PVE gameplay and the tears will most certainly flow along with the Galaxy Chat screams. Want to overwork your CSRs and GMs by nothing more than making them referees? Put back in TEF. Want to make Galaxy Chat unreadable by any1 who doesn’t want to see long rants of obscenities? Put back in TEF.

– http://www.bloodfin.net/forum/archive/index.php/t-825.html

Why was the TEF system removed?

Too many edge cases, basically. Helpful actions got to be very… subtle. Is it a helpful action if you are grouped with someone from one side and trade an item with them while in the home of someone from the opposite side? That event triggered a temporary flag on you and since you were in an enemy’s home, you got automatically ejected; there might be an ambush waiting outside for you that you can’t even see while you load from a sudden teleport.

In short, the edge cases made it very griefable. And grief, while not the same thing as PvP, often runs in parallel. Trash talking, gloating, bad language, entrapment… all these things were happening with the TEF system. And why was it that people kept making the mistake of flagging themselves?

The biggest reason? Players who just wanted to treat Stormtroopers as, well, orcs. Monsters in a videogame that they could mow down without getting dragged into PvP. Having been trained through decades of games set in Star Wars to kill Stormtroopers when they saw them. Often, simply not even seeing the little icon indicating that this dude wearing some weird uniform was actually an Imperial informant, or something. Worse, not knowing whether a given other player might come after you the second you made a mistake.

For the cautious and savvy player, this wasn’t that big a deal. But cautious and savvy players aren’t at risk of subscription cancellation. They are already bought in. It’s less sophisticated players you need to worry about, and who will make the mistake, and get burned by it and quit.

The death of TEFs