Deborah Ager's Blog, page 9

December 31, 2012

Enough Light

Contributor’s Marginalia: Maryann Corbett on “Query on Typography” by Malachi Black

For all our concentration on sound in poetry—for all our stress on giving readings and attending them, and on bright new journals that present the sound file along with the poem—most of us who love poems and who make them are writing them and reading them, mostly silently, to ourselves. We are using a medium that involves making marks on a surface, which we expect other people to pass their eyes over and make sense of. The marks, and the physical act of making those marks, thus become important in themselves, no matter whether the marked surface is paper or screen. That explains why, alongside the abundant supply of poems about poetry, there’s also an abundance of poems about the written word and letters and the act of writing. Writing such poems is a way of getting a new perspective by changing the focal length of the observation. Move in close, very close, and you see differently.

There are genres and subgenres of these observations. The writing hand itself, for example: As far back as the Exeter Book, a riddler in Old English talked about the three fingers of the pen-hand as travelers together over the black road of the ink. I’ve puzzled over paleography and penmanship in my own work. Then there are the individual letters. Seamus Heaney, in “Alphabets,” reinhabits the mind of the child learning letters and numbers, seeing at first only the shapes like “a swan’s neck and a swan’s back.” Another subtype involves seeing the letters as pure shape in a quirkier and more grown-up fashion, one we can see in Karl Elder’s “Alpha Images.” Yet another subtype uses a sort of pathetic fallacy of letterforms, investing the shapes of the letters with feelings. (It’s not surprising that poets do this, since type designers themselves do it.) Such poems make the letters, or the features of a type design, into characters in a narrative, as in James Merrill’s “b o d y,” and Sarah Sloat’s “Typeface #54” and others. Katrina Vandenberg threads together many different types of narrative connections out of the evolution of letter forms, all the way back to the Phoenicians.

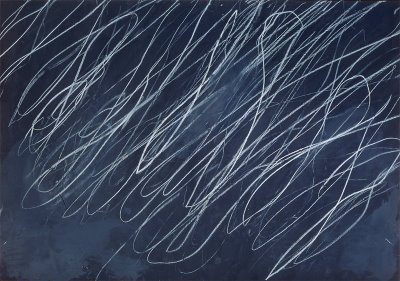

Untitled, Cy Twombly

Malachi Black’s “Query on Typography” does something different from all of these, something a little more abstract:

What is the light

inside the opening

of every letter: white

behind the angles

is a language bright

because a curvature

of space inside

a line is visible

is script a sign

of what it does

or does not occupy

scripture the covenant

of eye and eye

with word or what

the word defines

which is source

and which is shrine

the light of the body

or the light behind?

The poem asks how meaning is made: by the figure, or by the ground? It only suggests the obvious answer, but in the course of asking it implies and recalls much else. Much of its multivalent meaning comes from linebreaks and minimalist punctuation, so that the reader can and should read the same group of words in several ways.

It does this trick first with the language of physics, since it begins with the basic question “What is the light,” and the linebreak forces us, at least for a moment, to see that unit of sense as a question in itself. But the more whole question is, “What is the light/ inside the opening/ of every letter,” a metaphorical as well as a physical question that wants to know how it is we come to understanding at all. Later, across a linebreak, we find more physics, with some geometry: “a curvature/ of space inside/a line….” References to the lines and angles and curves of geometry keep appearing.

But so also does the language of the religions of the Book. The poem asks “is…scripture the covenant,” prompting us to recall that Scripture consists of those two familiar Covenants. Reading on, we find that the question is longer: is writing “the covenant of eye and eye,” which can be understood as the two eyes working together as usual, or as the necessary cooperation of the writer’s understanding with the reader’s. And we go on: Is writing “the covenant/ of eye and eye/ with word or what/ the word defines”? “Word” of course is full of religious suggestion: the Logos, and the scriptura that is famously sola for many. The surface question is simply, What part of the operation is shape-perception, and when does meaning take over? A deeper question is, Does the reader or the writer control? Sometimes we’re not sure which question or statement we should be perceiving. Is the poem declaring “the word defines which is source and which is shrine”? Or have we begun a new question: “which is source and which is shrine”? Is it “the light of the body,” the shape of the letter-form (there’s Scripture again, “the light of the body is the eye; if therefore thine eye be single, thy whole body shall be full of light….”) Or is it “the light behind,” in the background? Behind the reader’s eyes? The writer’s? Some other mind’s, deeper yet? No question here stays put; it shifts its shape away from what we expected.

And as a formal counterpoint to the sense, the poem locates its sound devices where we don’t expect them. In a poem that seems to be in a/b half-lines on the model of Old English alliterative verse, the rhymes, slant rhymes, and assonances are all on the a halves, leaving the right-hand line breaks without any kind of chime where we most anticipate having one:

What is the light

inside the opening

of every letter: white

behind the angles

This feels exactly backwards, like white text on a black ground, until we reach the end and find that the poem ends with a a-line—

which is source

and which is shrine

the light of the body

or the light behind?

—clicking shut neatly with another long i—or should I say “eye”?—sound.

Is the poem’s observation profound, or is it a commonplace? Better, I think, to call it fundamental. A foundation of human vision is the ability to distinguish, to locate boundaries between one thing and another. I’ve read that in Islam, for Ramadan, the hours of fasting begin when there is enough light to distinguish a white thread from a black one. On time, which has no demarcations of its own, we impose limits because our minds need to mark off one thing from another. Consider the importance of dark and light for our minds, of figure and ground in our lives, as we will mark off one year from another tonight. Happy New Year.

—Maryann Corbett

Maryann Corbett lives in St. Paul, Minnesota, and works for the Minnesota Legislature. She holds a doctorate in English from the University of Minnesota and is the author of two books of poetry: Breath Control (David Robert Books, 2012) and Credo for the Checkout Line in Winter (Able Muse Press, forthcoming in 2013) as well as two chapbooks. Her work has appeared in many journals in print and online, including River Styx, Atlanta Review, Measure, and The Dark Horse, as well as a number of anthologies. She is a past recipient of the Lyric Memorial Award and the Willis Barnstone Translation Prize. She has new work forthcoming in PN Review and Modern Poetry in Translation. Her poem, “Campus and Dinkytown,” appears with Malachi Black’s “Query on Typography” in 32 Poems 10.2.

Maryann Corbett lives in St. Paul, Minnesota, and works for the Minnesota Legislature. She holds a doctorate in English from the University of Minnesota and is the author of two books of poetry: Breath Control (David Robert Books, 2012) and Credo for the Checkout Line in Winter (Able Muse Press, forthcoming in 2013) as well as two chapbooks. Her work has appeared in many journals in print and online, including River Styx, Atlanta Review, Measure, and The Dark Horse, as well as a number of anthologies. She is a past recipient of the Lyric Memorial Award and the Willis Barnstone Translation Prize. She has new work forthcoming in PN Review and Modern Poetry in Translation. Her poem, “Campus and Dinkytown,” appears with Malachi Black’s “Query on Typography” in 32 Poems 10.2.

December 28, 2012

The Genres We Ignore

Review of Jimmy and Rita: A Verse Novel by Kim Addonizio (Stephen F. Austin State University Press, 2012)

Genre-bending—the prose poem, flash-fiction, novels in stories, literary biography, and, more to our purpose, the novel in verse—is particularly appealing these days. Some recent book contests accept only manuscripts that challenge classification, and even readers and writers who are more comfortable in traditional genres often feel curious about what they might be missing. Like children reluctant to go to sleep on the hunch that something good will happen once they go upstairs, we wonder what possibilities are bound up in the genres we ignore.

And yet, those of us who think of ourselves as lyric poets necessarily dwell within the possibilities and richness of the lyric tradition. We like to believe we know the novel’s limits. We admire it while acknowledging it’s simply not what we do. By and large the same is true for short stories, plays, and even novellas. Still, working (and reading extensively) in another genre might lend new insights to the forms we know best.

Robert Hass and David Foster Wallace have forced many of us to encounter the strange and possibly false dichotomy of prose poems and flash fiction. These genres have always seemed to me differentiated primarily by who writes them (poets write prose poems, fiction writers write flash fiction), and this distinction of origin governs what we notice, what’s present and what’s missing. Both can be rewarding and infuriating. Reading a prose poem, we might question whether line breaks might not improve a piece, or, alternatively, what the work has gained from the rhythms of prose. A piece of flash fiction may trim away some of narrative’s fat, but then sometimes seems to fall short of delivering what we really want from a story, narrative arc or the hard-earned transformation of perspective and understanding. At its best, flash fiction makes you question why any story needs to be so long. Done badly (or even normally), prose poems can seem lazy and flash fiction clever. Still, writers work in them; the dream persists.

I was drawn to Jimmy and Rita, in part, because of these questions. Primarily, I wanted to know what one could squeeze out of a novel in verse: how much narrative complexity could be leant to the poem, how much richness and torque of language could be added to the novel.

I was drawn to Jimmy and Rita, in part, because of these questions. Primarily, I wanted to know what one could squeeze out of a novel in verse: how much narrative complexity could be leant to the poem, how much richness and torque of language could be added to the novel.

“Novel” does not seem a word aptly applied to this book. Although it contains many compelling micro-stories within the poems, there is not enough of an overall narrative arc, nor enough transformation from beginning to end, to fulfill the expectations that word engages. It does function as an increasingly complex and interesting dual character study, with stories and secondary characters interspersed. In terms of one organizing story line, it is the love story of two drug addicts struggling with poverty, addiction, alcoholism, and confusion. The thing I appreciated most about this book is its elucidation of a particular kind of love affair. The love between Rita and Jimmy, because of who they are and the circumstances of their lives, is continually embattled: they fight with each other and others; they are in and out of jail, prostitution, and bad jobs; they disappear for stretches of time; and neither of them is even healthy enough in his or her own right to merit normal romantic expectations. Each fails the other and him or herself. Yet, everything in this story, the affirmation of the two voices, the pattern of reunions at any cost, and the general thrust of the narrative towards increasing certainty in their love, suggests the utter permanence of their relationship and its primacy in their imaginative lives if not always their actual lives.

What Addonizio compellingly explores is the paradox that a relationship that seems so doomed is indivisible and in fact immune to not only any, but all of the worst challenges that can threaten people and their relationships. The last lines of the book, in Rita’s voice, “Jimmy is looking at me and I know/ he loves me, I know/ he isn’t ever going to stop,” is not a high point creatively, but it does successfully convey the pure momentum of their connection, as if they are both immune to everything, even death, by the force of their love. This kind of relationship does exist and can be easily misinterpreted as your run-of-the-mill disaster by even intimate onlookers. In truth it is really something rare and miraculous. Not many writers could do this unusual kind of relationship the justice Addonizio does.

The book falls firmly within a twenty-first century understanding of “verse.” Addonizio’s poems are casually narrative, usually medium-lined (with a few prose poems), and sometimes formally experimental. The most experimental poem is a kind of lineless table or chart of four columns and seven rows of words, often repeated (“cigarette” appears five times). While I did not find this successful, other poems, such as the very short “My Name,” are. The book’s dialogues, as well as its shifts between prose and lyric poems, provide spontaneity and movement to the book that could not be had in prose. I consider this a productive capitalization of poetry’s resources within a narrative project.

The book falls firmly within a twenty-first century understanding of “verse.” Addonizio’s poems are casually narrative, usually medium-lined (with a few prose poems), and sometimes formally experimental. The most experimental poem is a kind of lineless table or chart of four columns and seven rows of words, often repeated (“cigarette” appears five times). While I did not find this successful, other poems, such as the very short “My Name,” are. The book’s dialogues, as well as its shifts between prose and lyric poems, provide spontaneity and movement to the book that could not be had in prose. I consider this a productive capitalization of poetry’s resources within a narrative project.

If you are confused because you remember Addonizio publishing Jimmy and Rita in 1997, you are right: “Jimmy and Rita” was originally a poem, then a book published by BOA Editions, and then the basis for a novel, My Dreams Out in the Street, published by Simon and Schuster in 2007, before the present incarnation of this novel in verse published this year by Stephen F. Austin State UP. Addonizio outlines all of this in the book’s introduction, explaining that she “couldn’t let these two go.” It seems to me that she’s found in them a way into many other stories besides theirs, and they work for exploring the themes of poverty and violence, among others. These characters are not compelling enough in themselves to necessarily merit three books, but they may be more of a form for her: a way into the creative process, an organizing principle, the light she uses to find each poem.

—Jasmine V. Bailey

December 24, 2012

Lovely Rot

Contributor’s Marginalia: Traci Brimhall on “Corpse Flower, Brooklyn Botanic Garden” by Brandon Courtney

Like most readers, I love a good seduction, and Brandon Courtney’s poem seduced me on several levels.

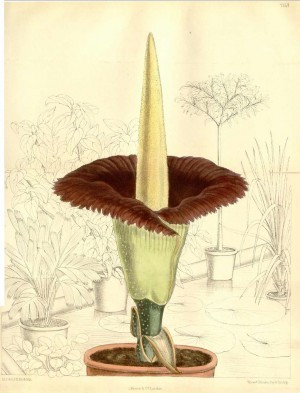

This poem incites my logophilia from the first line: “It’s not the spadix’s perfect candling, lepered/with pollen.” I admit to a poor working knowledge of floral anatomy, so I looked up spadix to see what was lepered with pollen. (Everyone should do this. I could describe the phallic spike rising out of a flower but wouldn’t you rather see it for yourself?) Although candling has several definitions, I like to think this is a reference to the practice of shining a light behind an egg to see the growth of the embryo. And lepered! My mother grew up near a leprosarium, and I recently discovered that leper colonies once had their own monetary system. That doesn’t have anything to do with Courtney’s poem, but it’s what his first sentence summons in me. My curiosity. My history. My pleasure. That fertile, upright spadix is lepered with pollen? That lush spike is flecked with festering sores? Who’s not seduced by that?

Amorphophallus titanum

Courtney’s verbs are straight up sexy, if I may say such a thing about a poem that describes a flower that smells like a corpse. After all, Wallace Stevens said “Death is the mother of beauty.” I may try and stretch it further to say there’s something arousing about decay. But to return to the verbs—pistils are shrapneled, inflorescence bandages its spathe, stinkhorns blister the compost, sand fleas feather a dead man’s eyes. See what I mean? Sexy.

If this poem tantalizes my love of language first and second, it finishes me off by referencing one of my favorite myths—Samson slaying the lion. In the Biblical story, Samson slays a lion on his way to ask for a woman’s hand in marriage. On his way to the wedding, Samson notices that bees have made a hive of the dead lion’s body, and he eats some of the honey. In Courtney’s poem, flies take the place of the bees, and a soldier stands in for the lion. I may not have thought of Samson at all if it hadn’t been for Courtney’s use of “honeycomb” to describe the actions of the flies. Delicious. I mean, awful, but it’s so particular, so horrifyingly alive that I can’t help but look.

Although his reference may not have been deliberate, I was glad that myth came buzzing to the surface of the poem. Samson offered a riddle to his groomsmen: “Out of the eater came something to eat. Out of the strong came something sweet.” The answer, of course, is honey from a lion, which only Samson knows. It’s a beautiful impossibility, and he wasn’t sharing his answer. Courtney offers what he knows but not as a riddle or a trick. He gives us a linguistically rich poem full of beauty, death, and humanity, a poem where heaven gathers on the flint’s tip. Out of a thousand days of waiting comes the flower made flesh, lepered beauty, lovely rot.

—Traci Brimhall

Traci Brimhall is the author of Our Lady of the Ruins (W.W. Norton, 2012), winner the Barnard Women Poets Prize, and Rookery (SIU Press, 2010), winner of the Crab Orchard Series First Book Award. Her poems have appeared in Kenyon Review, Slate, VQR, New England Review, Ploughshares, and elsewhere. She’s received fellowships from the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing, the King/Chávez/Parks Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Her poem, “After All the Lullabies Vanish From the Library,” appears with Brandon Courtney’s “Corpse Flower, Brooklyn Botanic Garden” in 32 Poems 10.2.

Traci Brimhall is the author of Our Lady of the Ruins (W.W. Norton, 2012), winner the Barnard Women Poets Prize, and Rookery (SIU Press, 2010), winner of the Crab Orchard Series First Book Award. Her poems have appeared in Kenyon Review, Slate, VQR, New England Review, Ploughshares, and elsewhere. She’s received fellowships from the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing, the King/Chávez/Parks Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Her poem, “After All the Lullabies Vanish From the Library,” appears with Brandon Courtney’s “Corpse Flower, Brooklyn Botanic Garden” in 32 Poems 10.2.

December 17, 2012

Bait

Contributor’s Marginalia: Hastings Hensel on “After the War” by Matthew Thorburn

I’m a sucker for good fishing poems—mainly because I like to fish, but also because fishing is a rich and natural, if obvious, metaphor. I won’t be the first to point out that angling in the watery depths is like angling in the psychological depths—both hinge on that moment of discovery, when something hidden breaks the surface after a period of struggle.

Matthew Thorburn’s “After the War” is, at first glance, a narrative fishing poem. It takes as its subject a scene from Gunter Grass’ novel The Tin Drum, though Thorburn converts and translates the scene admirably—I like his line control, his syntax, the way the poem naturally unfolds and ends with a subtle yet haunting image.

But I want to consider two things in particular—the title and the speaker—and how these two things work together to give us both a fishing poem and a poem of profound psychological experience.

Breton Fishermen, Paul Gauguin

Thorburn only mentions war in the title, and we presume it is World War II, given the acknowledgement to Grass, but it is perfectly universal enough to suggest any war. But “war,” as we know, is such a loaded word that anything after it resonates with all the pain and destruction and elegy the word implies. In this way, the title operates in a similar fashion to the opening paragraphs of Hemingway’s short story “Big Two-Hearted River,” in which the narrator only briefly mentions war so that all that follows—an otherwise mundane play-by-play of a hiking and camping trip—takes on even more significance.

Here too we have something simple and significant: a man fishing for eels “After the War,” when survivors must be innovative with the decimated world around them—hence the fisherman’s extemporaneous use of a “rotting horse head” for bait.

But who are these survivors? Who is watching this fisherman? Who is this observer, sensitive enough and close enough to notice “the coarse gray rope” and the “dented gray bucket”? Who is relating this scene to us?

It is, we learn in the eighth line, “we starving children”—a nice, surprising use of the first-person plural point-of-view.

And now this poem has me, for I admit that I’m also a sucker for the first-person plural point-of-view—I think of Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily” or an early Conrad novel—because it suggests gossip, a kind of collective experience. But here the first-person plural is even more affecting because it is from the generation that grew up in war’s aftermath, and whose childhood memories must be steeped in horror. Of course they have “wished” for a “mighty fish”—not just because children are always mesmerized by fish, or because it is a nice internal rhyme, but because war has made them, presumably, really damn hungry.

And the simplicity of this longing recalls for me even more fiction: the opening to Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s “The Handsomest Drowned Man in the World,” in which the children of a primitive beach village see something strange floating towards them. At first they think it is an empty ship, then a whale, but then they finally realize it is a drowned man.

Indeed, the children of Thorburn’s poem witness something like the children of Marquez’s short story—a memento mori that, at first glance, they “couldn’t understand,” but in the end is likely to stay with them forever. (And, in fact, has stayed with them ever since the event, as evidenced by the use of the past tense.)

So in this way Thorburn’s poem enacts that which it describes. The poem itself is memorable and haunting, and is likely to stay with a reader like me, especially since I live in a small inlet town on the Atlantic coast, where pulling things out of the water—crabs, oysters, clams, fish—is a way of life.

The other day, in fact, I went out to toss my crab traps and, because I was thinking about Thorburn’s poem, found myself following this terrifying but necessary line of self-interrogation: What if war came here? What if war came here and tried to destroy all that is before us, the people and the place, all that we love, our happy leisure?

It was a chilling thought, to be sure, but when the world around me returned, simple and clear, I found myself seeing anew the dead fish heads crammed in the bait holder—the stillness of their black eyes, the way the small droplets of salt water had splashed over their frozen, wide-mouthed, significant expressions.

—Hastings Hensel

Hastings Hensel is the author of a chapbook, Control Burn. He lives in Murrell’s Inlet, South Carolina. His poem, “Winter Inlet Arrangement,” appears with Matthew Thorburn’s “After the War” in 32 Poems 10.2.

Hastings Hensel is the author of a chapbook, Control Burn. He lives in Murrell’s Inlet, South Carolina. His poem, “Winter Inlet Arrangement,” appears with Matthew Thorburn’s “After the War” in 32 Poems 10.2.

December 7, 2012

‘Tis the Stevens

The closest feeling to those anticipatory Christmas Eves of childhood comes courtesy of Wallace Stevens. I find myself often reading Stevens in the winter and especially over the holidays, when the pairing of Stevens’ chilly voice and those spices of sound connect so well to the Christmas atmosphere. As a child, the strange notion that Santa Claus actually entered my home and left gifts under our tree filled me with both a giddiness and that special detachment that comes with the suspension of disbelief (as a child, I had no evidence that Santa could be real—even if I didn’t know the laws of physics and was scientifically ignorant, I had never seen anything but a bird fly and knew how tight our chimney flue was). I kept myself distant from the reality to preserve the illusion. In other words, Santa Claus resisted my intelligence, as Stevens said a poem should. Now, I read Stevens with the stillness of anticipation, expecting the impossibility of the verse, believing it despite not understanding it. From “Snow and Stars”:

The grackles sing avant the spring

Most spiss—oh! Yes, most spissantly.

They sing right puissantly.

Perhaps I read Stevens this time of year because his poems reflect the only type of Christmas atmosphere I can endure: mostly solemn, mostly isolated, and if there is to be cheer, it must be diluted thoroughly into the first two attributes (The hymn “O Come O Come Emmanuel” encapsulates this dynamic). On Christmas Eves the midnight ritual at the Episcopalian church of my childhood was somber, liturgical, and ornate. During the candlelit mass, I groggily sang from the hymnal while the robed clergy led the congregation. Despite experiencing the heights of anticipation (Christmas morning was just hours away), it was all incredibly peaceful, too. And dark. I think many of Stevens’ poems reflect this solemnity and peace, “The Snow Man,” a particular holiday favorite, especially.

Christmas is still a time of expectation, of long-waiting, and of solemn, low-grade cheer for me. Our cheeks grow rosy with the cold. We have our families and our homes, but the very act of gift giving reflects a perpetual lack in, or limit to, our lives. Stevens’ poem, “Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour,” reflects the familial solidarity I feel during the holidays. It is wistful, mysterious, and humble. Its deliberate tercets deliver a complex syntax that makes reading it aloud a lovely, private carol. It is a poem of candlelight and warmth against the cold, of the private experience of togetherness that embodies this season:

Christmas is still a time of expectation, of long-waiting, and of solemn, low-grade cheer for me. Our cheeks grow rosy with the cold. We have our families and our homes, but the very act of gift giving reflects a perpetual lack in, or limit to, our lives. Stevens’ poem, “Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour,” reflects the familial solidarity I feel during the holidays. It is wistful, mysterious, and humble. Its deliberate tercets deliver a complex syntax that makes reading it aloud a lovely, private carol. It is a poem of candlelight and warmth against the cold, of the private experience of togetherness that embodies this season:

Light the first light of evening, as in a room

In which we rest and, for small reason, think

The world imagined is the ultimate good.

This is, therefore, the intensest rendezvous.

It is in that thought that we collect ourselves,

Out of all the indifferences, into one thing:

Within a single thing, a single shawl

Wrapped tightly round us, since we are poor, a warmth,

A light, a power, the miraculous influence.

Here, now, we forget each other and ourselves.

We feel the obscurity of an order, a whole,

A knowledge, that which arranged the rendezvous.

Within its vital boundary, the mind.

We say God and the imagination are one…

How high that highest candle lights the dark.

Out of this same light, out of the central mind,

We make a dwelling in the evening air,

In which being there together is enough.

—Ben Glass

Benjamin Glass lives in Columbus, Ohio with his wife and daughter. His work appears in Gulf Coast, Pleiades, Unsplendid, and The Wallace Stevens Journal.

Benjamin Glass lives in Columbus, Ohio with his wife and daughter. His work appears in Gulf Coast, Pleiades, Unsplendid, and The Wallace Stevens Journal.

December 4, 2012

Start Checking Your Mailboxes for 32 Poems 10.2

32 Poems 10.2 shipped yesterday, and we couldn’t be more excited about this gathering of poems now on its way to our readers. The new issue features work by Malachi Black, Traci Brimhall, Kwame Dawes, Alexandra Teague, Charles Wright, and too many other excellent poets to list here.

If you haven’t ordered your copy yet, subscribe today.

November 30, 2012

2013 Pushcart Nominations

32 Poems is proud to nominate the following poems for 2013 Pushcart Prizes: Paul Bone’s “Moment of Dante” (10.1), Traci O’Dea’s “The Body” (10.1), Peter Kline’s “Invitation” (10.2), Malachi Black’s “The Beekeeper’s Diary” (10.2), Rosalie Moffett’s “Sunday Evening Meeting for Worship at 1435 Columbia St Apt 2″ (10.2), and Matthew Thorburn’s “After the War” (10.2).

November 5, 2012

Songs of Unreason by Jim Harrison

Jim Harrison’s thirteenth volume of poetry, Songs of Unreason (Copper Canyon Press, 2012), is initially surprising for its thickness: unlike his other single-volume books, which are generally the standard 75 pages or so, this book contains 141 pages of poetry. One reason for this book’s longer length is the inclusion of a long poem, “Suite of Unreason,” comprised of very short unnumbered sections. This is a surprising and exciting structural step for Harrison, who usually sticks to a uniform formal pattern of one-to-two page narrative poems. He solves the problem of how to organize the book around a long poem by placing sections of the suite on the left-hand pages with stand-alone poems facing them on the right-hand. The manuscript also begins and ends with poems that do not belong to the long poem. Like most complex structural solutions, this is both gratifying and problematic. The spacing of the long poem’s short, imagistic sections across the book keeps that project in our mind as we move through the other poems. Had the suite been its own section, whether at beginning, middle, or end, it would have been a break from the rest of the book, or suggested its opening or closing. As it is, the suite often interacts richly with the narrative lyric poems. Nevertheless, the sense of the long poem as an entity is harder to glean in such a format.

Perhaps the most surprising element of this long poem is Harrison’s choice to begin it with an epigraph that is not a quote but a sort of very brief prologue: “Nearly all my life I’ve noted that some of my thinking was atavistic, primitive, totemistic. This can be disturbing to one fairly learned. In this suite I wanted to examine this phenomenon.” As a writer and reader, I am immediately mistrustful of such an analyzing, assessing statement at the beginning of a poem: I am sensible both of the risk to Harrison of creating expectations which must then be lived up to or surpassed. I am equally sensible that my pride as a reader is automatically engaged: it’s my business to decide what kind of thinking goes on in these poems. And of course the benefits and the pitfalls of such a gesture both occur in their turns. By creating the expectation of “atavistic” and, even more strangely, “totemistic” (how does he mean this to differ from “totemic?”) thinking, we look for those qualities in the short poems comprising the long, and in the best poems feel that is what we have found. One section I thought was particularly successful as a poem and in terms of answering these expectations:

Azure. All told a year of water.

Some places with no bottom.

I had hoped to understand it

but it wasn’t possible. Fish.

Like the entire long poem, this section is haiku-like and very reminiscent of the Zen poetry written by sages (often hermits) in the Eastern tradition (Po Chu-I and Basho came to my mind). To me, the long poems seemed less atavistic, primitive, or totemistic, and more contemplative in the private-cosmic way of the Zen poetic tradition.

In another section Harrison writes, “we find many oval deer beds/ of crushed grass. Their bodies are their homes.” This poem certainly has the strong rhetorical voice so fundamental to Harrison, but it also nears the structure of a haiku and certainly attains the revelation-through-image that characterizes the experience that defines haiku beyond its form restrictions. Based on Harrison’s initial self-assessment, we might expect the poems to have more violence, sex, or hunger in their themes, or a more ruthless or disengaged voice. In fact they are very observant and compassionate in a way that is not only uniquely human, but unique to humans who have undertaken important spiritual commitments in how they view, interact with, and interpret the world.

In another section Harrison writes, “we find many oval deer beds/ of crushed grass. Their bodies are their homes.” This poem certainly has the strong rhetorical voice so fundamental to Harrison, but it also nears the structure of a haiku and certainly attains the revelation-through-image that characterizes the experience that defines haiku beyond its form restrictions. Based on Harrison’s initial self-assessment, we might expect the poems to have more violence, sex, or hunger in their themes, or a more ruthless or disengaged voice. In fact they are very observant and compassionate in a way that is not only uniquely human, but unique to humans who have undertaken important spiritual commitments in how they view, interact with, and interpret the world.

The same is not always true in the other poems, which generally observe the world in a more quotidian, rather than timeless, way. These poems strike many different tones and concerns. Some are playful, such as in “Xmas Cheeseburgers,” where the speaker describes making brie hamburgers for the farm dogs to buoy his (and their) Christmas spirit. Many of the poems tell apparently confessional stories of Harrison’s life, and often those of his dogs or other animals in his world. The dominance of animals as characters in this book enhances the sense of the poet as a Buddhist or simply hermit figure who has renounced the complications of the world and looked deeply, and with passionate care, into the concerns of creatures simpler (and perhaps with more to offer) than people. Wisdom—as a pursuit, but far more as something groped toward through living, and especially through the writing of these poems—is inarguably the primary work of this poet. In his many glowing rhetorical passages, clear gestures to his attempts to put his finger on great truths, or perhaps one great truth, are manifest. In “René Char II” he writes, “hallelujah/ is the most impossible word in the language./ I can only say it to birds, fish, and dogs.” This line is important both for its oblique ars poetica (how to praise is the central problem of living and writing) and for its explanation of the role of animals, who seem to permit him to say the most difficult things. The lack of response that animals represent, the one-sidedness of the declaration, and that being the only way to enable the utterance, puts me in mind of writing as a way to speak to people, saying the most difficult things, without having to face them.

In the poem “Grand Marais,” Harrison writes of a bear that frequents his yard to eat sunflower seeds meant for the birds and sometimes falls asleep there, frightening the dog: “He doesn’t give a shit about violent storms/ knowing the light comes from his mind, not the sun.” Here, again, an animal enables the epiphany that is not the bear’s but Harrison’s, and again seems like a way of saying “hallelujah:” the light is coming from within the bear. This is one of the best examples of Harrison’s wonderfully rich and adamantly earthy voice yielding an exalted thought. From earlier books, such as In Search of Small Gods, we are familiar with this pantheist, mystical, or Quaker tendency in Harrison to seek God and the agency of God in humble places. In the poem “Horses,” he writes, “This is another unanswerable question/ to haunt us with the ordinary.” This is another informal ars poetica, one that effectively illuminates Harrison’s style across his prolific work. He reiterates it in “Poet Science:” “It is life’s work to recognize the mystery/ of the obvious.” It is Harrison’s greatest feat that he can consistently deliver such daring rhetorical comments throughout a long book of poems and largely pull them off.

Still, the poems I admire most are those in which Harrison flexes more of his craft than keen observation and trenchant rhetorical comment. In the poem “Sister,” Harrison remembers a sister that died long ago. The quality of his looking at the moon and remembering, as an old man, the sister who died while still very young has a fundamentally haunting quality. It also toys with time, making it seem somehow permanent and standstill, as if the moment of her death is trapped in the present no matter how long he lives. The fact of his looking at the night sky, as he does in many of these poems, reinforces this idea: the events we observe in the sky have in many cases happened thousands of years ago, yet appear to go on now. The heavens work into a powerful motif representing in part the trick of time as it is perceived by people: it is meant to move linearly, but in perception is at times concurrent or recurrent. He writes, addressing the sister, “Maybe you drifted upward as an ancient/ bird hoping to nest on the moon.” The line break at “ancient,” in part because of the imagism and Zen Buddhist bent of the entire book, especially this poem, suggests ancients as in ancestors, especially in Chinese tradition. This would suggest one who both came and went before you and who continues to exist as a philosophical and energizing force, and seems an apt metaphor for his sister. Of course we soon realize that the word modifies “bird” and that is when the image takes over the rhetorical observation we were expecting from the rhetorical style of these poems. This line is Songs of Unreason and Harrison at their best: a compelling personal memory is rendered using his characteristically strong rhetorical voice via a startling and successful image.

There are other interesting formal idiosyncrasies in this book, such as the presence of several prose poems (a genre Harrison has sometimes worked in before) and an informal second long poem in the form of seven “River” poems. Even with the “Suite,” however, the structural play in this book is gratifying, but not the star. As always, it is Jim Harrison’s vision, voice, and his hard-gained and always tremulous wisdom that carry these consistently risky poems and make the book worth reading.

—Jasmine V. Bailey

October 16, 2012

The City of Poetry by Gregory Orr

Reviewed by Jasmine V. Bailey

Gregory Orr has earned a reputation for writing compellingly across genres: he is the author of ten poetry collections as well as four books of criticism. He also wrote an acclaimed memoir about his childhood and his struggle with grief after the early, confusing loss of a brother. In widely-published essays he has written about his experiences as a civil rights activist in the sixties, when as a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee he was jailed and beaten in Alabama. Orr has also a poetry editor, a fine teacher, and the founder of the University of Virginia MFA program. His most recent publication, The City of Poetry, is a chapbook of poems, the tenth in Sarabande Books’ Quarternote Chapbook Series.

Chapbooks strike many lovers of poetry as refreshing in the way novellas and one-act plays can be: less commercially-codified units of poetry that defy the fingertips’ expectations of width, the internal clock’s notion of how long it takes to read a book of poems, and aesthetic assumptions about what the shape and arc of a book should or can be. Like their counterparts in other genres, chapbooks can be incredibly satisfying units of poetry: long enough for thoughts and motifs to develop across poems. When done well they seem to break at their natural point without the need for sections or great thematic or formal shifts to successfully survive a longer mode. Chapbooks can be aberrations in a poet’s oeuvre, affording an opportunity to break away from a prevailing style or set of concerns, or they can be sort of coda to previous or ensuing longer works. In this case, The City of Poetry seems very much an extension, and possibly the conclusion, of a project Orr has undertaken in his previous book-length collections, Concerning the Book that is the Body of the Beloved and How Beautiful the Beloved.

Concerning the Book that is the Body of the Beloved surprised many followers of Orr’s work for its departure from his previous poetry. Still lyrical and imagistic, the poems in this volume constructed their own mythic universe and used a much more conversational, sentence-based rhetorical style than poems in his previous books. The world of that book coheres around the Osiris myth: specifically his death, brief resurrection by Isis, and reincarnation. Orr lays that metaphor aside eventually to develop his own powerful and complex metaphors which are represented by the most basic words, first among them, “Beloved.” In this book, the Beloved might be represented by, or represent, Osiris or any dead or departed loved one, including, one imagines, the poet’s brother. The Beloved is perceived as lost and therefore grieved by the lover (speaker), who is left behind. But the Beloved lives on in Art, especially Poetry. The central metaphor is spun out into a rich web in the first book, and the groundwork is laid for the second book, and indeed, for this chapbook, in which the healing, eternal space of Poetry becomes the central theme.

Concerning the Book that is the Body of the Beloved surprised many followers of Orr’s work for its departure from his previous poetry. Still lyrical and imagistic, the poems in this volume constructed their own mythic universe and used a much more conversational, sentence-based rhetorical style than poems in his previous books. The world of that book coheres around the Osiris myth: specifically his death, brief resurrection by Isis, and reincarnation. Orr lays that metaphor aside eventually to develop his own powerful and complex metaphors which are represented by the most basic words, first among them, “Beloved.” In this book, the Beloved might be represented by, or represent, Osiris or any dead or departed loved one, including, one imagines, the poet’s brother. The Beloved is perceived as lost and therefore grieved by the lover (speaker), who is left behind. But the Beloved lives on in Art, especially Poetry. The central metaphor is spun out into a rich web in the first book, and the groundwork is laid for the second book, and indeed, for this chapbook, in which the healing, eternal space of Poetry becomes the central theme.

Poetry’s main metamorphosis in this chapbook is that, instead of being treated an amorphous space (synonymous with music and other arts) as it was in the first and second books, it is here conceived as a city inhabited by those who write and whose writing is the brick and mortar of the ever-expanding metaphorical landscape which begins to generate its own energy. “Soon it became a village,/ And next it was a town.// And now it makes its own weather.” The City forms the structure of the book, in which all the poems are like grottos, corners and studio apartments, windows into the imaginative universe of the poet and his past. Orr’s imprisonment in Alabama is touched on in one poem shockingly free of blame. In it, he remembers being allowed to keep a book of Keats’ poems and reading “Ode to a Nightingale.” “And I was there with that bird/ I could just glimpse/ By shinnying up the bars of my cell:// Mockingbird in the magnolia.” This poem is powerful for its biographic candor and authenticity, its attitude of gentle wonder, and also for subtle explosions like the transplantation of the images of the Keats’ poem with those images native to the foreign place where he was imprisoned.

I believe this book of poems (which reads as a long poem) is equal parts love and praise. Many of the poems are worshipful in a hymn-like style: “O, poem/ Of the beloved.// O, beautiful body/ whose every orifice is holy.” Here, the strong Whitmanian impulse to sanctify and praise the body is contained within a formal structure reminiscent of Dickinson. This is a poem that is gentle but insistent and convincing, as the entire long poem finally is.

—Jasmine V. Bailey

October 8, 2012

Contributor’s Marginalia: Traci O’Dea Muses on “Will You Tell Me if You Will” by Marielle Prince

Even though it’s sixteen lines instead of fourteen, I want to call this poem a lazy sonnet. Not lazy in a derogatory sense. Lazy in a sexy, salty, Southern, too-hot-to-do-anything-other-than-sit-here-and-fan-myself sort of way. Like a heat wave. I live in the Caribbean, so if this poem came from here, and I wanted to classify it as a sonnet, then it would be a sonnet on island time. Island time is not lazy. It’s just laid back, as in, “life’s too short to stress about getting anywhere too fast.” Like Julia Alvarez’s sonnets (also Caribbean). But all this talk about heat and islands has nothing to do with the poem other than its structure. It is open. With those spaces in the middle of each line, like forced caesuras, making the reader pause before every “or.” For example, the first stanza reads:

The question was red it was on her mouth or it was black it was

penciled in around her eyes or the mark of it slung around her

waist or dangled from her ears or it hung down her back

it swayed like the hypnotist’s watch chain or chimes in a soft

breeze not quite making a sound

The structure of this poem works in its favor. If instead of the caesuras, the poet had used line breaks before each “or,” then the poem would lose its sexy, lazy, open vibe. It would read more staccato and almost robotic, like this:

The question was red it was on her mouth

or it was black it was penciled in around her eyes

or the mark of it slung around her waist

or dangled from her ears

or it hung down her back it swayed like the hypnotists watch chain

or chimes in a soft breeze not quite making a sound

The Walking Lesson, Jacek Yerka

“Will You Tell Me if You Will” is also, starting from the title, almost palindromic. Palindromes are circular in content but linear in form. This poem’s linear content circles back on its self, encouraging the reader to begin anew as the “she” in the poem begins each day with the same question on her lips—a question that is never asked or answered. The “hypnotist’s watch chain” in the fourth line mimics the palindromic movement of the poem. The hypnotist can move his watch like a pendulum or in a circular fashion. But all I’m really trying to say is that the poem has a hypnotic, tide-like pace that speeds up and slows down. The first stanza starts furtively, like the question is destined to be asked and answered, but then we lose the question and only have “the mark of it”—a question mark—which is then “slung around her waist,” so by the time we get to the “chimes in a soft / breeze not quite making a sound,” the pace has slowed down to let the reader know that this question is probably not going to happen. And the fact that this question will not be asked has been long accepted by the speaker.

The second stanza starts much more pragmatically: “You saw the question,” it says. Unlike in the first stanza where every new metaphor built on the one before, in the second stanza, each metaphor turns the previous one on its head.

You saw the question or looking right at it didn’t see or

you saw and its language was foreign or too familiar to notice

or you saw it you covered it quickly with your hands as if it were

shameful or yours to guard or full sun in the direction

you were headed

So, in this case, the palindrome has transformed into a metronome—moving back and forth, without any forward trajectory or circular nature. This stanza offers opposites struggling against each other like magnets—equally strong when the metaphor has moved to each pole—yes, the question’s language was foreign; yes, it was too familiar to notice. Even though the “or” (instead of an “and”) before each proposed metaphor tells the reader that it is not all these things, the poem and its magnetic nature still suggest that the question can be all those things at once.

The three stanzas can be separated into Her, You, and Them, with the Her and You making the argument that would typically be made in a sonnet’s octet. The third stanza is the Them, in that both the Her and the You appear, and this makes up the resolution of the sestet. Up until this point, the Her and the You had not interacted, even though the relationship was implied. The third stanza brings them together with one, intimate hypothetical, metaphorical gesture: “or you unclasped the question behind her back.” The Her and the You are also brought together through the combination of the two previous stanza’s implementation of the metaphors—in the third stanza, some of the metaphors build on their predecessors while others oppose.

And her eyes were closed or they were open and she was blinded

or you unclasped the question behind her back or she sighed and

laid it aside herself or she dropped it and found it in the morning

and hid it under her clothes or saved it and went to bed with it as

if it were you or the dark or an alarm set to wake her the

same each day

I’m not typically a fan of unpunctuated poems. Nor do I like clumsy line breaks on words like “the,” but “Will You Tell me if You Will” works without traditional grammar and punctuation and, even, a line break on an article. Again, the structure reinforces the breathy rhythm of the poem that has unconventional pauses and cyclical momentum. Had the poem ended with the line “the same each day,” it would’ve snapped shut—something of which I am typically a fan. But Marielle Prince’s poem has been, so far, set up not to snap shut, so the ending line could not have been anything other than an arbitrary, unforced line break that leads the reader to start the poem again. The best poems lead the reader back to the beginning, and “Will You Tell Me if You Will” does so through both its content and its structure. Lastly, I applaud the editors of 32 Poems for selecting a poem that fits so well with an issue that also seems to flow in a cyclical pattern—starting and ending with Dante and with the same hypnotic, tide-like pace throughout. This issue (like this poem) feels like a record album—conscientious and cohesive.

—Traci O’Dea

Traci O’Dea lives in the British Virgin Islands where she is an English lecturer. Her poems have appeared in Poetry, Measure, Unsplendid, and others. She is an Associate Editor for Smartish Pace.

Traci O’Dea lives in the British Virgin Islands where she is an English lecturer. Her poems have appeared in Poetry, Measure, Unsplendid, and others. She is an Associate Editor for Smartish Pace.