Deborah Ager's Blog, page 5

April 12, 2013

Weekly Prose Feature: “Tethered to Nothing: A Review of Fowling Piece by Heidy Steidlmayer” by Caitlin Doyle

Heidy Steidlmayer’s poetry explores the uneasy relationship between existence and its opposite. Whether writing about romantic love, religion, mythology, illness, or motherhood, Steidlmayer often confronts the prospect of annihilation. Her debut collection Fowling Piece abounds with provocative negatives; the “nonimage” found on a brain scan, the muffled noise within an MRI chamber that verges on being “nonsound,” the “not-seeing” of an eye behind an eye-patch. In the book’s title piece, the speaker describes learning to hunt as a child:

The pull of guns I understand,

my father taught me hand on hand

how death is. Life asserts.

(Best take it like a man.)

I shot a dove, the common sort

and mourned not life but life so short

that gazed from death as if unhurt.

And I had nothing to report.

The unexpected and chilling last line registers a theme that pervades Steidlmayer’s work: the possibility that a human being can confront both life and death and ultimately find “nothing to report.” In the world of Fowling Piece, waves break and “come to nothing.” At an insect exhibit, the “empyrean opens / itself to nothing.” A woman irons until she’s pressed “each crease / breathless, to nothing.” “Agonal” explores the forces that threaten the “thereness” of a loved one’s body and, in “The Mask,” the speaker undergoes treatment for brain cancer, suspecting that she may be “tethered to nothing.”

Her poems orbit around the tension between the concrete and the intangible. Her work derives considerable force from the fact that, when she finds “nothing to report,” she reports on it anyway, reaching into and beyond the void. For Steidlmayer, words act as the tether that binds “thereness” and nothingness so that each can give definition to the other.

Throughout Fowling Piece, Steidlmayer demonstrates a level of technical accomplishment that suggests a belief in crafted language as a potential antidote to nihilism. In “Limbo,” she writes:

Because there is nothing there is that is not

worth dying for, we wait until our bodies take on

the stubborn musculature of sculpture, feel

where form, like everything fixed, gives

off a kind of grief

Steidlmayer masterfully breaks lines so as to simultaneously emphasize them as discrete units and as integral parts of a whole poem. “Because there is nothing there is that is not” both connects to the ensuing lines and stands alone as a statement that embodies the poem’s larger themes. The line, considered on its own, engages the idea that there’s nothing in existence that isn’t also essentially non-existent—“there is nothing there is that is not”—by nature of the fact that life and death may, as the poems in Fowling Piece so often speculate, contain no meaning. When examined in the context of “Limbo” as a whole, the line and the line break work together here to point toward a notion prevalent throughout Fowling Piece: the annihilation that threatens existence also gives it its value.

Many of Steidlmayer’s lines, when parsed like the first line of “Limbo,” bring to mind Keats’ idea that poets should strive to “load every rift with ore.” Compression comprises one of her most striking gifts as a poet. In “Limbo,” when she says that “form, / like everything fixed, gives / off a kind of grief,” she speaks not only of the human body’s form but also of the role that form plays in poetry at large. She packs reality’s sprawl into such tight and finely honed spaces that the pressure generated by its enclosure within her language often “gives off a kind of grief.”

Her use of formal restriction frequently heightens the impact of emotionally charged subject matter, as in the short two-stanza poem “The Coracle”:

I set you adrift in withies and pitch,

stripped of all sign I would know you by,

cradled in Oxskin, nursed by the gorse,

the wind dissolving your cries.

A bird on the mountain, a cork

to the sea, a far-off story of shore –

you float the salt-dark, a speck

vanishing the moment it’s more.

The poem’s exploration of containment, as the vessel sets forth to fend for itself, finds embodiment in the way the language’s form strives to contain the emotional largess of the subject matter. “The Coracle” also displays Steidlmayer’s consummate skill with assonance. She sends aural echoes through the poem with the “i” in “adrift,” “withies,” “pitch,” “stripped,” “Oxskin,” “dissolving,” and “vanishing,” just one example of a vowel sound that repeats to hypnotic effect in the “The Coracle.” Steidlmayer’s ability to create sonic resonance with vowels is so notable and varied that it sometimes calls to mind the dense assonance of poets like Lord Alfred Tennyson, Edgar Allan Poe, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, while at other times chiming with the work of more contemporary masters of subtle vowel-music like William Carlos Williams and Sylvia Plath.

Another defining feature of Steidlmayer’s work, as evidenced in “The Coracle,” is her acuity with rhyme. When she writes in rhyme, she often plies a mixture of perfect rhyme and slant rhyme, as if to constantly remind readers that language’s form can almost—but not fully— control and shape the world it endeavors to contain. Interestingly, “The Coracle” ends with a perfect rhyme between “shore” and “more,” the only pair of perfect end rhymes in the piece. This suggests Steidlmayer’s desire to reach for the comfort of control, closure, and comprehensibility at the very moment when the poem most drifts beyond her reach; the coracle (and, by implication, the poem itself) becomes “a speck / vanishing the moment it’s more.”

Steidlmayer implies here that, although language only gestures toward containing the unknown, the gesture might be all the more beautiful because it cannot entirely achieve its aim. The last line of “The Coracle” hits on an essential element of Steidlmayer’s art. She confronts the way that meaning vanishes the moment one tries too forcibly to either see or fabricate “more” of it. Her work thrives in the space between the human desire to know the universe and the human inability to ever fully do so.

When Steidlmayer falters, which is rarely, it usually occurs when a poem doesn’t “vanish” the “moment it’s more,” when she seems too bent on wrenching a definable something out of the nothingness that both intrigues and terrifies her. In “Pulling Up the Lawn Mushrooms,” she invites us to see a subtle parallel between the activity of removing mushrooms from a lawn and the process of transforming the world into language. But the final image of the mushrooms—“the small ones lift their long throats from the thatch / and whisper a thousand assurances”—seems like too neat a conclusion for a poet who so frequently acknowledges that turning the world into words rarely produces mere assurances.

Fowling Piece abounds with so many skilled and memorable poems that one almost never catches Steidlmayer stumbling. Against the grain of much contemporary poetry, her work achieves considerable strength and distinction because she embraces artifice without embarrassment. Steidlmayer often layers her poems with such a density of alliteration that her language seems to revel in calling attention to itself as language. In “Thistles,” she describes thistles as “clocks fully struck / in fields of fading flowers – / when the fires of summer come.” The repeated “f” sounds escalate as the poems progresses: “…famished stalks in full gale / that begin their telling once / all forms of telling fail.” Steidlmayer also relishes mixing levels of diction in a way that makes her readers subtly aware of language as a crafted medium. “Couples,” one of the most powerful pieces in the book, opens with a section titled “Cutlery,” in which her adeptness at blending varied registers of diction shines:

Midnight, the knives throw

shadows with showy precision

through my hesitant silhouette.

Old umbrage has brought me here,

unharmed, near missed, where

the thrown blade was your own,

untoward and very fast.

Steidlmayer captures the sharpness of the speaker’s emotional pain through the colloquial immediacy of phrases like “the knives throw / shadows.” Yet Steidlmayer’s language also achieves an effect mimetic of the speaker’s need to seek protection from that pain. Formal and distancing words like “umbrage” and “untoward” show the speaker’s desire to blunt, control, and intellectualize the hurt. The last line in particular, with its skillful combination of high diction in “untoward” and vernacular speech in “very fast,” typifies the tonal prowess that characterizes Fowling Piece. Steidlmayer’s decision to end with “very fast” implies that the speaker cannot truly distance or shield herself from the knives.

Steidlmayer’s vocabulary varies as widely as her diction. She frequently sends readers to the dictionary. Her poems abound with unusual words like “faience,” “orphrey,” “almoner,” “gloriole,” “echolalic,” and “lanthorne,” as well as an extensive lexicon of scientific terminology pertaining both to nature and to the world of modern medicine. Steidlmayer’s passion for attention-getting language, her dexterous use of rhyme and meter, her appetite for mixing diction registers, and her love of dense assonance and alliteration distinguish Fowling Piece as a unique debut collection. She wants the readers of Fowling Piece to never completely forget that, when encountering her poems, they interact with crafted objects made out of language. Steidlmayer highlights the materiality of words not to point at herself and say “look how skilled I am,” but rather to point at language itself and say “look at what can be done with it.”

In “Three Daughters,” readers find an image that powerfully resonates with the larger thematic concerns of the book. Steidlmayer describes dressing one of her daughters in a turtleneck:

I am pulling a blue turtleneck

on my second daughter,

her head comes up and out

as if she were rising from a drain.

She looks at me in relief and says,

I was gone.

The young child feels dislocated, erased, and temporarily annihilated – I was gone – and she re-emerges into the regular world with relief. Steidlmayer enters again and again into a space where both she and her readers feel “gone.” In “The Eye-Patch,” she describes how the patch tricks her palsied eye into “not-seeing as it sees / in the round sea of its dark cup: the mind in its weedy prominence / opening like a terrible mouth.” The patch both turns her eye into a “not-seeing” organ surrounded by blackness and reteaches her imagination to “see” in an entirely new way. Immersed in a nether region of erased vision, the mind opens “like a terrible mouth.” In the unforgettable poems of Fowling Piece, Heidy Steidlmayer presses our ears to that “terrible mouth” so that we can experience language’s capacity to reach toward filling the abyss.

—Caitlin Doyle

↔

Caitlin Doyle’s poetry has appeared in The Atlantic, The Threepenny Review, Boston Review, Black Warrior Review, Measure, Best New Poets 2009, and many others. She has received residency fellowships at a variety of artists’ colonies, including the MacDowell Colony and the Ucross Foundation. She has held the Writer-in-Residence post at St. Albans School and the Emerging Writer-In-Residence position at Penn State University, Altoona. Her recent honors include the Amy Award in Poetry through Poets & Writers Magazine and a Tennessee Williams Scholarship in Poetry through the Sewanee Writers Conference. This upcoming fall, she will hold a residency fellowship as a Writer-In-Residence at the James Merrill House in Stonington, CT. She is currently at work toward the completion of her first book-length poetry manuscript.

Caitlin Doyle’s poetry has appeared in The Atlantic, The Threepenny Review, Boston Review, Black Warrior Review, Measure, Best New Poets 2009, and many others. She has received residency fellowships at a variety of artists’ colonies, including the MacDowell Colony and the Ucross Foundation. She has held the Writer-in-Residence post at St. Albans School and the Emerging Writer-In-Residence position at Penn State University, Altoona. Her recent honors include the Amy Award in Poetry through Poets & Writers Magazine and a Tennessee Williams Scholarship in Poetry through the Sewanee Writers Conference. This upcoming fall, she will hold a residency fellowship as a Writer-In-Residence at the James Merrill House in Stonington, CT. She is currently at work toward the completion of her first book-length poetry manuscript.

Each Friday we will publish a new essay, review, or interview for the 32 Poems Weekly Prose Feature, edited by Emilia Phillips. If you have any questions or comments about the series, please contact Emilia at emiliaphillips@32poems.com.

April 11, 2013

Poetry Month, Day 11*: Chad Davidson Recommends From the Fishouse

From the Fishouse: An Audio Archive of Emerging Poets

Matt O’Donnell and crew have compiled the most ambitious listening booth project of contemporary poetry the world has seen. On this fantastic site, you can listen to the inimitable Ilya Kaminsky read (or, really, declaim) his poems to some stunned crowd. You can marvel at a Matejka, bawl at the beauty of a Bauer, and so forth. They also sport an eclectic array of readings–full poetry evenings recorded live. I just listened to Brian Turner reading from Phantom Noise in Denver and was not unimpressed. In short: From the Fishouse is to the Academy of American Poets’ listening booth as a jacked-up mountain lion is to a tabby kitten named Ed. Sure, Ed the kitten is cute, but if you’re serious about your killing, you go with the jacked-up mountain lion. Matt O’Donnell is poetry’s jacked-up mountain lion, and we welcome the carnage.

The website also spawned its own anthology, complete with a CD of recordings. My sense is that From the Fishouse will continue to be the place to come to listen to contemporary poetry, while also returning the act of recitation to its rightful place–at the center of poetry culture.

Isn’t it great to be fishy?

—Chad Davidson

*Throughout Poetry Month 32 Poems will use this space to praise presses, journals, and readings series that bring poetry to us in a special way. Our hope is that we can point new fans in their direction and publicly thank editors and curators for their work. Check in with us again tomorrow for another poet’s recommendation.

↔

Chad Davidson is the author of From the Fire Hills (forthcoming), The Last Predicta (2008), and Consolation Miracle (2003), all on Southern Illinois UP, as well as co-author with Gregory Fraser of Writing Poetry: Creative and Critical Approaches, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009). He is an associate professor of literature and creative writing at the University of West Georgia near Atlanta.

Chad Davidson is the author of From the Fire Hills (forthcoming), The Last Predicta (2008), and Consolation Miracle (2003), all on Southern Illinois UP, as well as co-author with Gregory Fraser of Writing Poetry: Creative and Critical Approaches, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009). He is an associate professor of literature and creative writing at the University of West Georgia near Atlanta.

April 10, 2013

Poetry Month, Day 10*: Mary Biddinger Recommends Big Big Mess Reading Series

This is a messy little love letter for the tremendously loveable BIG BIG MESS READING SERIES in Akron, Ohio. Akron may already be known for its tires and its tireless love of grit and rust and sweat, but the BIG BIG MESS deserves its own corner of the proverbial postcard. This reading series, which is one of the most giddy and eclectic I’ve witnessed, was founded by Nick Sturm, and is presently curated by Alexis Pope and Mike Krutel. It’s a monthly affair, and takes place at Annabell’s Bar & Lounge, 782 West Market Street in downtown Akron.

I’m the sort of person who always feels compelled to scream in a quiet library, or to slap two books together in glee during a particularly enjoyable poetry reading. Both of these activities are not only permissible, but encouraged, at the BIG BIG MESS. Listeners don’t just hear the poems, they feel them, and that’s okay. Furthermore, the BIG BIG MESS has door prizes, ranging from shake weights to hot new poetry collections donated by small presses. The lineup is always top-notch, the drinks are cold, the bar stools are wobbly, and the words bring down the house every time.

—Mary Biddinger

*Throughout Poetry Month 32 Poems will use this space to praise presses, journals, and readings series that bring poetry to us in a special way. Our hope is that we can point new fans in their direction and publicly thank editors and curators for their work. Check in with us again tomorrow for another poet’s recommendation.

↔

Mary Biddinger’s most recent poetry collection is O Holy Insurgency (Black Lawrence Press, 2013). She is also co-editor of The Monkey and the Wrench: Essays into Contemporary Poetics (U Akron Press, 2011). Her poems have recently appeared or are forthcoming in Barrelhouse, Bat City Review, Blackbird, Crazyhorse, Crab Orchard Review, Forklift, Ohio, Guernica, Gulf Coast, Pleiades, Quarterly West, and Redivider, among others. She teaches literature and poetry writing at The University of Akron, where she edits Barn Owl Review, the Akron Series in Poetry, and the Akron Series in Contemporary Poetics.

Mary Biddinger’s most recent poetry collection is O Holy Insurgency (Black Lawrence Press, 2013). She is also co-editor of The Monkey and the Wrench: Essays into Contemporary Poetics (U Akron Press, 2011). Her poems have recently appeared or are forthcoming in Barrelhouse, Bat City Review, Blackbird, Crazyhorse, Crab Orchard Review, Forklift, Ohio, Guernica, Gulf Coast, Pleiades, Quarterly West, and Redivider, among others. She teaches literature and poetry writing at The University of Akron, where she edits Barn Owl Review, the Akron Series in Poetry, and the Akron Series in Contemporary Poetics.

April 9, 2013

Poetry Month, Day 9*: James Arthur Recommends The Knox Writers’ House Recording Project

One of my favorite websites right now is The Knox Writers’ House Recording Project, an audio archive of contemporary American writers reading their work. The readings have been recorded by three former Knox College students, and are indexed geographically, city by city. The students—Emily Oliver, Sam Conrad, and Bryce Parsons-Twesten—began the project under the mentorship of Knox College faculty poet Monica Berlin. At first Oliver and her friends recorded writers living in the Midwest, but now they’ve added recordings from Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, North Carolina, Texas, and California. The idea, according to the project’s website, is “to help cities listen to themselves, to understand how place influences art, and how that art changes depending on origin, on audience, on influence.”

Something unusual about this archive is that most of the writers have been recorded not at a podium, addressing a large audience—but instead, sitting in their own offices, living rooms, and kitchens, speaking softly into a microphone. These are intimate recordings, and the intimacy comes across. A few pieces I especially love are Jericho Brown’s “Charms Against Lightning, is available through Copper Canyon Press.

April 8, 2013

Poetry Month, Day 8*: Kyle McCord Recommends Gulf Coast

As the lead content editor for LitBridge, I spend a good bit of time trying to promote small presses, up-and-coming journals, residencies that might not have the visibility of MacDowell or the Vermont Studio Center. I strongly believe in that: helping the little guys get their feet in some doors. However, when Emilia Phillips asked me to write about an entity in the world of poetry that deserves my praise, I thought I might buck the trend a little bit. I want to praise a journal that already garners plenty of accolades because, in the case of this magazine, I think that praise is merited.

Gulf Coast. Let’s talk about Gulf Coast.

When I graduated from college, I was living in a cabin in rural Ohio in voluntary poverty. It’s a longer story, but I worked for Brethren Volunteer Service helping rebuild church communities. I had few books, but I did have magazine subscriptions. There were five magazines I read, and I poured over them. Among them was Gulf Coast.

What I loved then and what I still love about Gulf Coast is that through the years they’ve managed to cultivate an aesthetic that doesn’t definitively put them in one camp or another. The poems they publish are not easy narratives or avant garde experiments. Irony finds a comfortable stride in the work they publish, no doubt, but that irony is always tinged with some element of sincerity. Certainly there are some flares for verbal acrobatics, but the poems seem cohesive. While their swath is broad, they’re one of the few journals that puts together what feels like a magazine with a clear vision that isn’t easily aesthetically pigeonholed. What I find is that Gulf Coast continually publishes poems that are unapologetically beautiful or pleasantly surprising or both.

Aesthetically, the magazine itself always knocks me out too. Girl screaming at what looks like a single-celled organism? You had me at single-celled organism, Summer 2010. Colorful impressionist trees? Sure, Winter 2012! From the highly-functional website, to the dynamite logo, to the magazine printed on pages which actually seem to give off a bit of shimmer, everything about Gulf Coast seems to give off an air of professionalism, of a magazine that takes every space it occupies seriously.

I will cease my gushing here, but be assured that I could say more. In those years since I lived in that cabin in Ohio, I’ve since acquired more books. In fact, I’ve got a pile from AWP starting with Jason Bredle’s Carnival staring me down in the best way possible right now. But I still finding myself returning to the pages of Gulf Coast when I don’t feel like taking any chances, when I just want to sit down with some poems that are beautiful and well-wrought. That’s what Gulf Coast exists to do in the world. To find what I should read, what I didn’t even know I needed to read, and put it all in one magazine. And I’m mighty glad they’re out there doing it!

—Kyle McCord

*Throughout Poetry Month 32 Poems will use this space to praise presses, journals, and readings series that bring poetry to us in a special way. Our hope is that we can point new fans in their direction and publicly thank editors and curators for their work. Check in with us again tomorrow for another poet’s recommendation.

↔

Kyle McCord is the author of three books of poetry including Sympathy from the Devil from Gold Wake Press. He has work featured in Boston Review, Denver Quarterly, Gulf Coast, Third Coast, Verse and elsewhere. He’s the co-founder of LitBridge and co-edits iO: A Journal of New American Poetry. He teaches at the University of North Texas.

Kyle McCord is the author of three books of poetry including Sympathy from the Devil from Gold Wake Press. He has work featured in Boston Review, Denver Quarterly, Gulf Coast, Third Coast, Verse and elsewhere. He’s the co-founder of LitBridge and co-edits iO: A Journal of New American Poetry. He teaches at the University of North Texas.

April 7, 2013

Poetry Month, Day Seven*: Lee Upton Recommends Brick

I recommend the international magazine, Brick, founded in 1977 and perpetually interesting. It comes out of Toronto with new as well as long-esteemed voices, reviews, photographs, illustrations, conversations and interviews, and reflections on film and history. The contents are distinctive for overall vividness and no-nonsense candor and just the right healing touch of eccentricity. The issues are beautifully solid, even nice to hold. Nowhere near as heavy as an actual brick but substantial. I just hefted the current issue to confirm just how nice the magazine is to hold, and while flipping through I paused on the copyright page for a quotation from Rilke that reflects the magazine’s spirit: “Works of art are of an infinite loneliness and with nothing to be so little appreciated as with criticism. Only love can grasp and hold and fairly judge them.” In the same issue there’s Teju Cole, Alice Oswald, Colm Tóibín, a celebration of Mina Loy, Jim Harrison with “Eat or Die,” and an interview with Edward St. Aubyn. I haven’t found a dull page in any issue yet. Somehow I missed hearing about Brick for many years and hope with this note to remedy that situation for whoever happens to be reading this at the moment.

—Lee Upton

*Throughout Poetry Month 32 Poems will use this space to praise presses, journals, and readings series that bring poetry to us in a special way. Our hope is that we can point new fans in their direction and publicly thank editors and curators for their work. Check in with us again tomorrow for another poet’s recommendation.

↔

Lee Upton’s most recent book is Swallowing the Sea: On Writing & Ambition, Boredom, Purity & Secrecy (Tupelo). In 2014 a collection of her short stories, The Tao of Humiliation, is forthcoming from BOA Editions. She is a professor of English and writer-in-residence at Lafayette College.

Lee Upton’s most recent book is Swallowing the Sea: On Writing & Ambition, Boredom, Purity & Secrecy (Tupelo). In 2014 a collection of her short stories, The Tao of Humiliation, is forthcoming from BOA Editions. She is a professor of English and writer-in-residence at Lafayette College.

April 6, 2013

Poetry Month, Day Six*: Adam Vines Recommends Northwestern UP

Mike Levine and the folks at Northwestern UP have published some of the strongest poetry collections I have read over the past few years. The books look fantastic, and Northwestern covers a broad range of aesthetic sensibilities—Greg Brownderville to Jehanne Dubrow to Greg Fraser to Christina Pugh to Nikky Finney to Amit Majmudar to Alicia Stallings.

—Adam Vines

*Throughout Poetry Month 32 Poems will use this space to praise presses, journals, and readings series that bring poetry to us in a special way. Our hope is that we can point new fans in their direction and publicly thank editors and curators for their work. Check in with us again tomorrow for another poet’s recommendation.

↔

Adam Vines is an assistant professor at UAB and editor of Birmingham Poetry Review. His recent poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Poetry, Southwest Review, and Gulf Coast, among others.

Adam Vines is an assistant professor at UAB and editor of Birmingham Poetry Review. His recent poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Poetry, Southwest Review, and Gulf Coast, among others.

April 5, 2013

Poetry Month, Day Five*: Traci O’Dea Recommends Orchises Press

I first encountered Orchises Press a few years back at the Associated Writing Programs conference when Denise Duhamel was signing Kinky, her poetry collection about the Barbie doll. In the center of the crowd of fans, Denise Duhamel sat—all hair and smiles and smarts—and beside her was Orchises bespectacled mastermind Roger Lathbury—humbly passing her books to inscribe and clearly pleased as punch with all the commotion. That year, I read Kinky and giggled at Duhamel’s precise, insightful analysis of what it means to be plastic and what it means to be human which are sometimes both the same thing.

At the next AWP, I found Orchises Press again, and admired a copy of Eric Pankey’s Heartwood. I will admit that the volume’s metallic blue cover first attracted me to the book, but the poems inside sang to a tune that reminded me of moments of Robinson Jeffers’ long poem “Hungerfield.” I was impressed with Roger’s taste and range in the choice of poets that he published. He gave me a copy of Heartwood. Poetry is his passion, and he wants people to read it.

In that way, Roger might be a bit old-fashioned. While his publications all tend to have striking, unique, true-to-the-content covers, he is most concerned about what’s inside. The website for Orchises Press does not include multimedia clips or flashy images. Instead, it offers, for each book in the catalog, concise and thoughtful one- or two-line summaries or reviews, mostly written by Roger himself, which demonstrate a deep understanding and appreciation of each book he’s published. Additionally, a click on the link of the author’s name, leads to the cover art and an excerpt from the tome—either a poem or a few paragraphs of prose, depending on the book. He wants people to read his books because he knows readers will be rewarded.

In addition to contemporary poets such as David Kirby, Lia Purpura, John Poch, and Terri Witek, Orchises Press also publishes new prose as well as reprints of classics such as Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper” and an edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses which is described in the Orchises catalog as follows: “After many attempts to produce an authoritative text, free of typographical error and embodying Joyce’s corrections, it seems that the experience of reading the book as it first appeared—typographical mistakes, bad type and all—most enables contemporary readers to experience Joyce’s masterpiece as its first excited readers did.” I think that description exemplifies Roger’s own excitement for words and how they can move readers. An excitement that shows in the books that he publishes.

from Kinky’s “Apolcalyptic Barbie”

by Denise Duhamel

“…Maybe she was in shock. Mayber her emotions

were nuclear-tampered. She wished she could run

away from it all, and for the first time, her wish came true.

She pushed the books from her chest, stood up, and stretched.

An unlikely Phoenix rising from the ash, she rejoiced.

She had never moved on her own before…”

from Heartwood’s “Old Brickyard Road”

by Eric Pankey

“…If I remember right,

that was the first quarry pit—

seen from the sheer cut ledge,

half-full of rainwater, stale

and growing algae-green—

I convinced myself to dive

into, convinced that water

would be cooler than the day’s

gathering heat and steam,

just to find what held me up

was warm as the air

and yet dark. Hardly water…”

—Traci O’Dea

*Throughout Poetry Month 32 Poems will use this space to praise presses, journals, and readings series that bring poetry to us in a special way. Our hope is that we can point new fans in their direction and publicly thank editors and curators for their work. Check in with us again tomorrow for another poet’s recommendation.

↔

Traci O’Dea lives in the British Virgin Islands where she is a writer and English lecturer at H. Lavity Stoutt Community College. Her poems have appeared in Poetry, Measure, Unsplendid, and elsewhere. She also volunteers for Smartish Pace.

Traci O’Dea lives in the British Virgin Islands where she is a writer and English lecturer at H. Lavity Stoutt Community College. Her poems have appeared in Poetry, Measure, Unsplendid, and elsewhere. She also volunteers for Smartish Pace.

Weekly Prose Feature: “An Omnibus Review of Tomás Q. Morín, Lisa Russ Spaar, and Allison Benis White” by Emilia Phillips

In a time when the mundane abounds and, in an attempt to subvert it, many poets bet all their lunch money on irony’s thin pony, the three poets here devise the extraordinary by other means. Morín, Spaar, and White all exhibit a virtuosity in their craft and yet, despite the technicality that reveals itself in close reading, each one earns its keep through what’s at stake in the poems. Among my favorite new works, these collections are reviewed alphabetically by author’s last name.

With this review, and all the future reviews published on 32 Poems online, I hope that readers will take our stance of critical appreciation as a spur for experiencing the work themselves.

*

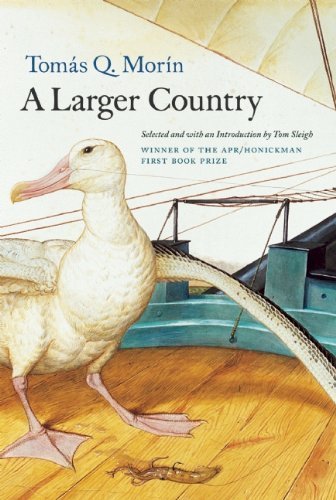

A Larger Country by Tomás Q. Morín

The American Poetry Review, 2012

A Larger Country not only expands the limits of our reading world geographically, with nods to European poets like Czseław Miłosz and Miklós Radnóti, it broadens our expectations of what can happen in a poem and the universe it creates, bending physics and probability. Often vaguely situated in a kind of alternate or hyper reality, Morín’s poems temper a Kafkaesque authority with an exuberance in tone like that of Gogol. Many of the poems confront readers with a conceit, as with “Karma”:

A Larger Country not only expands the limits of our reading world geographically, with nods to European poets like Czseław Miłosz and Miklós Radnóti, it broadens our expectations of what can happen in a poem and the universe it creates, bending physics and probability. Often vaguely situated in a kind of alternate or hyper reality, Morín’s poems temper a Kafkaesque authority with an exuberance in tone like that of Gogol. Many of the poems confront readers with a conceit, as with “Karma”:

When she came from the East, empty-handed,

the newspapers used words like raiment, blue, shimmers,

to describe her arrival in the hall of immigrants.

Under occupation she scribble solace.

Here we have a personified Karma on a kind of ambassadorial tour of an unidentified, presumably American, town. Karma seems bigger than the Beatles or the Dali Lama; the speaker(s) say that they “paraded her down the avenues / to . . . where her pink likeness / stood cut in granite.” On her customs/immigration form, she identifies her occupation as solace, but look how Morín’s phrasing totes another meaning: “Under occupation” could suggest that another person or group controls her or the place she’s in and, there, she writes about solace. Throughout the collection, readers will find moments where Morín deftly plays to two readings, like an underhandedly worded contract. Some readers, zealots of transparency, may beef about this grammatical duplicity, but take it as a testament to Morín’s scrutiny of language. And his playfulness.

What makes Morín’s forays into the absurd work is his knack for arresting imagery. “Karma” ends:

she counted the hours

under a birch somewhere, deathless, teaching

the hemorrhaging mouse at her feet about patience.

But Morín appeals not only because of imagery but also in how he warps the familiar into the outlandish:

He filled the sink with the trout who hit our lines,

crossed himself once, twice, then renamed and cut each one

—their vague eyes rolling—while I made ready to gently knuckle

each flayed beloved with garlic and thyme, an American John

to his American Jesus, humming my crazy songs

over the black faces of the plans I baptized in butter.

“The dead will only suffer butter,” he liked to say

Ritual, with its cousin religion, dodders through a number of the poems in A Larger Country, sometimes toward hilarity, as in the comedy of errors, “Egg Ministry.” Morín gives us the set up:

In a grim henhouse I find the faithful

clucking about the rapture,

and whether heaven is truly shallow and fresh

like a box of straw waiting for birth.

All eggs will break, I assure them . . .

As they consider this, a reddish, bouquet-crested hen

nods to sleep

But then we jump into the hen’s dreams where she sees

sticky, Egyptian hands

grinding a bold, yolk-yellow powder

for mixing with egg and water—

to paint skin, no doubt.

And, more associatively, we move toward Giotto who

will use it to ignite his poor saints’ heads,

while Botticelli will mute it for his Madonnas

whose petite, exhausted faces

in the flight-heavy dreams of hens would surely flake

and having flaked, leaf into the moist air

to spin and reweave a lost tribe of yolks

But, landing on firm ground again: “Such is the dream life of hens.” At the end, the poem turns away from the conceit and explodes onto “you are now a part of the ritual, / a necessary antagonist / to a faith no less fragile than your own.”

What Morín perhaps finds most viable about ritual and religion in poetry is their rhetorical character and their language forms. In an interview published by 32 Poems in March, Morín says that his goal in writing A Larger Country “was always to keep the strangeness of the poems in focus by using as a backdrop tried-and-true forms (sonnet, sestina, rhymes) that would hopefully anchor the reader.” When the speaker of “While Waiting for the Resurrection” addresses Miłosz, he says:

I know what you really wanted

was a sturdy sentence that would move meaning

patiently along the slick backs of verbs and nouns.

But this, most of all, seems like Morín’s intention. If we overextend the collection’s title into a metaphor, we might think about form as a means to map sovereign gestures, to know, if not expand, the borders of what we can understand. “[T]here is joy in our sheer movement / of a thing from A to B,” he writes in “Dumb Luck,” and

a sound

made realizes its purpose when it fills

a silence because that is what we do

when we are born.

A Larger County is filled with sound and movement. Consider the opening of “Our Prophets”:

It shouldn’t have surprised me while reading

Gorky’s remembrance of Tolstoy and devouring chicken

on a blanket in view of the muddy waters

that I should see a parakeet misnamed the Quaker parrot

by some scientist poet with a sense of humor

in the way their lime color drapes over

their backs and down each wing in a way that

reminds one of a key lime pie; though not

the one with the dome of meringue which resembles

the dress of a house finch, rather the wobbly

body of the sad supermarket doppelganger;

the imposter with the God-awful filling

tinted green by they of the white aprons

and soufflé hats who no doubt assume we are all children

Morín, unlike some associative poets, doesn’t have the nervous energy, the spastic lunges between images. Rather, we have a smooth ride in store for us, on the “slick backs of nouns and verbs.” Notice how, even when there’s not a rhyme, Morín provides us with slant rhymes or consonance: how the “n” sounds chime between “reading” and “chicken,” how the o with double consonants echo in “wobbly” and “doppelganger,” how the “n” sound returns for “filling”/ “aprons”/ “children.”

Regardless of Morín’s formal capabilities, the book entertains us with its cabinet of curiosities, its images, its often fabular and magical narratives, its humor, and its immense sensibility. Morín reminds us that we can be “loved again / and again by the words in a book,” and, if the reader allows it, that book will be A Larger Country, for, here, “we are finally / in the world we always said we wanted.”

*

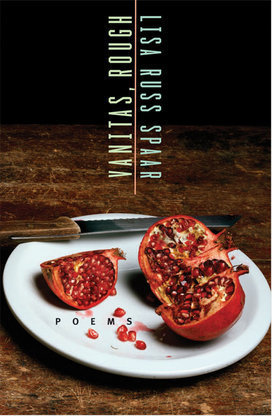

Vanitas, Rough by Lisa Russ Spaar

Persea Books, 2012

Lisa Russ Spaar’s fourth collection privileges us with the “lonely bliss of going / where the body cannot follow.” Though, in the poem, the place’s most likely death, Spaar enables us to achieve this bliss through other, healthier means: language. Throughout Vanitas, Rough, language serves not only as a vessel for information, it textures our reading with sonics that nearly enact experience, so that we may “imagine what’s unreal (soul, the other, desire, blah),” against Spaar’s own admission that sometimes it’s “perhaps impossible . . . in words, // to tell”.

Lisa Russ Spaar’s fourth collection privileges us with the “lonely bliss of going / where the body cannot follow.” Though, in the poem, the place’s most likely death, Spaar enables us to achieve this bliss through other, healthier means: language. Throughout Vanitas, Rough, language serves not only as a vessel for information, it textures our reading with sonics that nearly enact experience, so that we may “imagine what’s unreal (soul, the other, desire, blah),” against Spaar’s own admission that sometimes it’s “perhaps impossible . . . in words, // to tell”.

That’s not to say that the collection builds itself around imitative fallacy, that a poem called “Hibernalphilia”—that is, the fondness for winter—feels stark and dormant. Rather, in the opening nine lines of the poem, Spaar bathes us in detail:

Triangular glasses, brumal volts, gin,

frescade of pearls, plucked, sunned olives,

grave albino onions, juniper nip & the cusp of snow,

we sip slow, as at a glacier’s lip. Holy day.

I’m thinking fingerbone salad, the marginalia

of Emily Brontë, intricate skeleton keys,

not blade but the pierced heart, the bow

to which torque must be applied.

That blue note of exile in your eyes.

The language here verges on the tactile. Notice how the sharp sounds of “Triangular glasses” (and its six-syllables) suggest the sharp angles of the physical object; how the onion contains layers, as onions do, of description: grave, albino; how “the cusp of snow” hangs on the cusp of the line break; or, even more technical, how the stresses that abound in the phrase “we sip slow, as at a glacier’s lip” literally causes the reader to slow down, to sip on the line instead of gulp it down. As the subject matter moves to more delicate and intricate objects and appreciations, the language becomes more delicate and intricate with more polysyllabic words and complex vowel sounds like that we find in “marginalia,” “skeleton,” and “intricate.”

Perhaps I’m reading too much into the poem, but whether Spaar intends these gestures or if they come subconsciously to her, Vanitas seems to present an onomatopoeic representation of memory and emotion. Language and its contrivances likewise become a part of the imagery so that many of the poems wax ars poetica, though they aren’t that simple. We see “the spider’s nocturnal script” and “the world / in verbless fugue state”; we voyage into etymology, as in “St. Vogue”:

With a route in voguer, to sail—

as longing is root to Lent—

so the glamour of failing is again in season.

Here, the “heart speaks . . . in dactyls” and “Rime shackles . . . ankles”.

One could identify Spaar as a formal poet—and we’d be ignoramuses if we flew through the book without noticing her tendencies toward prosody and end rhyme—but this distinction diminishes her fluidity and skill. So often critics use “formal” pejoratively, as if it denoted formulaic verse, jigsaw balladry. Perhaps Spaar’s poems work beyond their formal construction because they situate themselves always in the tangible even when they respond to religious tropes, as in the sequence that includes “St. Home” and “St. Bed of Snow,” and art, as in “After Hokusai”:

then, climacteric, urn-thick cocks

tinted purple, in small, soft-bound limited editions,

lovers cramped into the pages, four tight corners,

labial folds, shell pale

kimonos, octopi prongs forcing mouths

& mons prone in sea-foam—.

But for this late self-portrait,

seamed neck, torso crooked over

bent cane: mere bone-black ink, sumi,

& just as ghostly, pulse-point pentimenti

of cinnabar, the soul

pushing its way out, regret

Spaar tells us: “To abstract is to surrender.” When it becomes difficult to finish a poem, to tell what happened, she gives herself the imperative of “Still, try” and launches into an attempt: “inkling flare, japonica flooded & skeletal. / The dawn genitive, hived, unstoppable.” Why? She tells us that, too: “Objects withstand the gaze / better than words.”

Vanitas, Rough provides us words that are as close to objects as they can get. Her poems slur the boundaries between two and three dimensional, living and reading. In doing so, each poem becomes dense and, though Spaar prefers short lyrics, often in couplets, it takes a long time to read each poem, to parse the sounds for comprehension. That said, the reader’s attention and effort is rewarded with acute meditations and bliss of the body.

Spaar doesn’t shy away from the erotic; the result, if I may say so, is sexy (if not occasionally grotesque). The “transfusion of flesh & gust,” the plait of fetish and description, yields, in the title poem, this passage:

In a panel of floor-propped mirror

your tongue in me is mine, too,

glass pear of the toppled goblet,

drunken wasp grazing semen yolk

of split, glazed oyster shells,

Death blowing soap bubbles

out the orbital sockets

Spaar, in a move rarely accomplished elsewhere, elevates language and description beyond mere practice, beyond craft, to near rapture. As poets, we deserve the sublimity of our medium, and when Spaar asks, “Is syntax erotic?” and then begs, “If so, please. Please read. Here.”—we’d be fools not to do so.

*

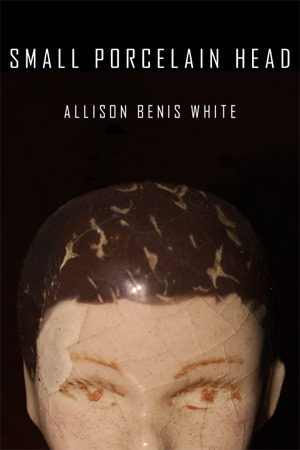

Small Porcelain Head by Allison Benis White

Four Way Books, 2013

“[T]o make dolls out of death is to make children,” writes Allison Benis White in her second book, a collection of untitled lyrical prose poems that, in the wake of an unidentified death, uses doll imagery as a kind of effigy for the irreconcilable and ephemeral—the body, god, and art. “[S]he is mute,” ends one poem, “as the moments I accept God or a make a voice from objects, pressing her stomach, pressing her stomach, not screaming.” With eerie precision, White sculpts her descriptions—

“[T]o make dolls out of death is to make children,” writes Allison Benis White in her second book, a collection of untitled lyrical prose poems that, in the wake of an unidentified death, uses doll imagery as a kind of effigy for the irreconcilable and ephemeral—the body, god, and art. “[S]he is mute,” ends one poem, “as the moments I accept God or a make a voice from objects, pressing her stomach, pressing her stomach, not screaming.” With eerie precision, White sculpts her descriptions—

For the easily broken heads of bisque or china, tin heads, made separately, cut and stamped from sheet metal, welded together, then painted or enameled in Saxony, now in boxes, on bodies dressed in black or maroon capes with fur collars, each shattered head exchanged for a metal one but it is not enough.

—and, elsewhere, dresses her subjects in the finery of lyric mediation:

If God is everything, then he is this emptiness and eyelids that close when her head is tipped back in the dark and click. If God is nothing.

The attention to detail in Small Porcelain Head elevates its subjects toward ekphrasis, as if the dolls, and the lost life that burdens them, are a kind of art or, at the very least, an attempt at it. For White, the body, and its death, seem deeply embedded in language, even poetry; White speculates about the possibility of speaking “with the fluency of dying” and asks, “What should I do with my mind? Think of the way it broke until the breaking is language.”

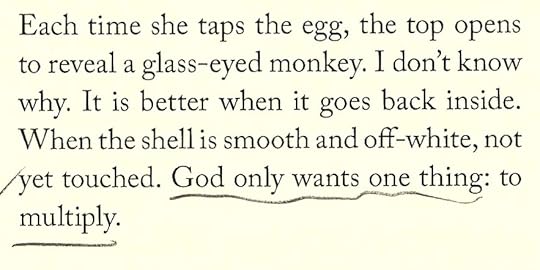

The prose form here provides as much texture as lineation. Wide margins and short, sometimes one-sentence, paragraphs affect the appearance of pentameter and stanzas. The end words, as they fall in the full-justification, feel deliberate—nothing out of place, nothing accidental. Even as I quote from the collection throughout this review, I worry I’m altering the poems, not doing their design justice. Because we cannot accurately reproduce the formatting through type, I’ve provided a scan of one of these poems below as a way to emphasize how important the appearance of the work is on the page:

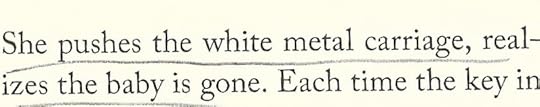

Look at how the first line opens into the second; how “I don’t know,” as a grammatical unit, seems to work with “to reveal a glass-eyed monkey.” And what about that ending!—the penultimate line literally multiplies when “multiply” wraps to the next line. This sort of faux-lineation abounds in the book, often with significance. Elsewhere, the hyphenation of “realizes” at the margin alters our reading by momentarily, and duplicitously, suspending the sentence’s meaning:

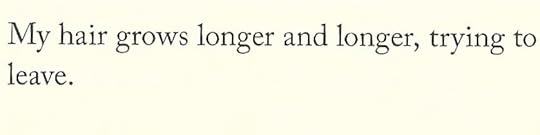

And see how the word “leave” literally leaves a line:

Is this intentional on the part of White? Four Way Books? My guess is yes, but regardless of whether or not this near impossible precision is accident or design, Small Porcelain Head gives us the prose poem at its most lyrical, most aware and elegant.

But that doesn’t mean that the poems’ poise conceals the rawness of the speaker’s voice, doesn’t mean that the grief here doesn’t turn toward violence. The imagery, often macabre, carries the tone here. “If description is a living thing . . . I want to say something that will look at me,” she writes and later provides us with “key turned, moaning, in the back of her head”; two torsos “sewn together at the waist”; “Mary . . . delivered from Marie. And the reverse, later, because she requires company.”

Sometimes, however, White addresses the concerns of the speaker head on:

. . . Because the operator activates the body like a glove puppet.

Because the novelty wears off quickly and the hand, withdrawn, leaves the body exhausted.

Because to live is to be entered vertically and repeatedly, the pain is love and making me.

At the core of all lyrical poetry, in whatever form, is, what White calls, the “mutual helplessness of seeing and being seen”—a tension between two beings, of the gaze between them. In this case, one of those beings is dead and the living is forced to play the role of the “other.” Constantly throwing her voice behind this other, White asks, “What’s left but obsession, handling the object over and over?”

Readers may find that they return to Small Porcelain Head again and again. Though, initially, a quick read, second and third encounters with these poems reveal the complexity of the form, that the meditations and images ameliorate each read, become more potent and insightful. As White suggests, “the desire to make and to cease are equal,” and each poem here seems to be doing just that: opening up to another poem while destroying the previous, coming into being just as it leaves. But take comfort from these poems if you can, White tells us: “[I]f death is a failure of imagination, we are alive.”

—Emilia Phillips

↔

Emilia Phillips is the prose editor of 32 Poems.

Each Friday we will publish a new essay, review, or interview for the 32 Poems Weekly Prose Feature, edited by Emilia Phillips. If you have any questions or comments about the series, please contact Emilia at emiliaphillips@32poems.com.

April 4, 2013

Poetry Month, Day Four*: Paul Bone Recommends Moon City Press

I first heard of Moon City Press because it published the excellent novel Morkan’s Quarry. The author of that book, Steve Yates, was the publicist at the University of Arkansas Press when I was a graduate student in the M.F.A. program there in the 90s. One semester, as an intern in the marketing department, I wrote and recorded short radio pieces on some of the Press’s titles, and preparing for the assignments allowed me to become familiar with the library, which includes many excellent histories of Ozark life, literature, and culture. This is also where I first became acquainted with poets like Billy Collins, John Ciardi, Miller Williams, Timothy Steele, Leon Stokesbury, Enid Shomer, Alice Friman, and Charles Rafferty, among others.

I mention the University of Arkansas Press because of the relationship it has with Moon City Press. Operating out of Missouri State University, Moon City has a short fiction award, Moon City Review (its literary journal), and a poetry chapbook contest. Moon City’s mission—“publishing stories, scholarship, and histories from the Ozarks”—provides a space for the region’s excellent writing to flourish.

While excellent work like Yates’ novel and Winter’s Bone have done a lot for literature from and about the Ozarks, in some ways the region is still largely misunderstood, in spite of a large body of work by earlier folklorists, ethnographers, historians, and writers like Vance Randolph and those published through UA Press. The Ozark region lacks the South’s deep history and tragic overtones, though it has inherited much from the South. Geographically it is an odd bird, too—in places it is prairie, in others steep mountains, pastoral and archaic at once. And there it sits on the edge of the vast plains, an edge, an island, a last pocket of isolation before the country flares into the open frontier.

Because I have roots in the region and am happy about its collaboration with UA Press, where early on in my education I read some important poets, I was glad to discover Moon City Press and its dedication to writing for and about a particular place.

—Paul Bone

*Throughout Poetry Month 32 Poems would like to use this space to praise presses, journals, and readings series that bring poetry to us in a special way. Our hope is that we can point new fans in their direction and publicly thank editors and curators for their work. Check in with us again tomorrow for another poet’s recommendation.

↔

Paul Bone is the author of Momentary Vision of the Assistant Meteorologist (Uccelli, 2005) and Nostalgia for Sacrifice (David Robert Books, 2013). He is chair of Creative Writing at the University of Evansville and co-editor of Measure.

Paul Bone is the author of Momentary Vision of the Assistant Meteorologist (Uccelli, 2005) and Nostalgia for Sacrifice (David Robert Books, 2013). He is chair of Creative Writing at the University of Evansville and co-editor of Measure.