Deborah Ager's Blog, page 8

February 11, 2013

Failure as Self-Protection

Contributor’s Marginalia: Renee Emerson on “Instar and Eclose” by Rosalie Moffett

Growing up in Hickory Withe, Tennessee, tent caterpillars shrouded the black-barked pecan trees lining the back half acre of our land. Once we got a good harvest there, until the worms did their work. I remember my father on a ladder with the handsaw, the branches falling webbed-white. I never thought of it as beautiful.

In Rosalie Moffett’s “Instar and Eclose,” there’s beauty in that destruction, destruction of the caterpillar becoming the gypsy moth, of the tree covered in web. Moffett takes what you would think would be a tired idea—the metaphor of growth and coming-of-age through the metamorphosis of the caterpillar to butterfly—and transforms it into thoughts on creation from destruction, failure as self-protection. Her lines and stanzas are concise, and the turns are quick, each couplet working as a poem on its own. “I know metamorphosis turns” the poem begins.

I read The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle to my eighteen-month-old daughter and think of this poem. In the book, if you’ve never read it, the caterpillar is ravenous—he eats, and he eats. Moffet captures that ravenousness. In this poem, “Everything / I’ve ever kissed / was a tree / in boy’s clothing” as the speaker moves beyond explaining what she knows of the cycles of the caterpillar (each an “instar”) and its emergence (“eclose”)—“I know metamorphosis turns / a kaleidoscope / into a caterpillar,” she writes—and into how she too is like the caterpillar.

Failure is transformed into something beneficial, a protection. It is so un-American to fail, and to see failure and destruction as beauty. We tend to be ashamed and afraid of failure. Here the failure is used as a “lure”, an “enticement” from what is “smaller, more / vulnerable.” What is that fragile thing worth protecting? Her soul, herself, perhaps.

She fully inhabits the role of caterpillar in the seventh stanza to the end; the focus shifts to her mouth, all that it has touched “ a tree” and each yawn “tasted like apples.” Yet she takes a step back from the poem in the last stanza—she “climbs / into the white silk gown . . . made by tent caterpillars.” She dons this persona to explain how a “ruin” can end “shimmering.” And this poem, never a ruin, does end shimmering.

—Renee Emerson

Renee Emerson’s poetry has been published in Indiana Review, Christianity and Literature, and Boxcar Poetry Review. She teaches at Shorter University and is the author of three chapbooks, most recently Where Nothing Can Grow (Batcat Press). She lives in Georgia with her husband and daughter. Her poem, “What to Wear,” appears with Rosalie Moffett’s “Instar and Eclose” in 32 Poems 10.2.

Renee Emerson’s poetry has been published in Indiana Review, Christianity and Literature, and Boxcar Poetry Review. She teaches at Shorter University and is the author of three chapbooks, most recently Where Nothing Can Grow (Batcat Press). She lives in Georgia with her husband and daughter. Her poem, “What to Wear,” appears with Rosalie Moffett’s “Instar and Eclose” in 32 Poems 10.2.

February 8, 2013

Weekly Prose Feature: “The Eolian Self” by Bruce Bond

Literary history written in broad strokes is, granted, an easy target. It is always more difficult to write such a history than to pick one apart. To account for major evolutionary shifts takes the assimilation of huge amounts of literature and thus constitutes a daunting undertaking, so much so that models of the vast tend to echo one another in some imaginary chamber of consensus. Especially as historical narratives fuel contemporary debate, the more sweeping assumptions beg reexamination in order to make more supple our literary affections and attentions, our sense of what the past has to say, or rather our changing views of what it just might say, as we read it once again. One historical simplification, now common in generalized diction of polemic, involves the Romantic turn in literature and its relationship to the often politicized issue of selfhood.

The mainstream view of the Romantics suggests that they continued a lyric tradition wherein a relatively unproblematic view of the self as defined and authoritative lays the ground for a heightened individualism, both poetic and political. In her introduction to the anthology American Hybrid: A Norton Anthology of New Poetry, Cole Swenson is not alone when she sees twentieth-century American poetry as informed by two dominant sensibilities, one thread of which “inherited a pastoral sensibility from British Romanticism, emphasizing the notion of man as a natural being in a natural world, informed by intense introspection and a belief in the stability and sovereignty of the individual” (xvii). While much of this statement is true, what Romantic introspection yielded remains highly subversive with regard to the “stability and sovereignty of the individual.” Moreover, the very sense of “transcendence” or “metaphysics” that Swenson associates with the Romantic tradition figured largely in conceiving the individual as deeply haunted and unstable, bound at its roots to the depths of the sublime.

If we accept Swenson’s sketch of history, the alternative tradition derived from a spirit of French symbolist innovation is “marked” by a different concept of meaning as immanent as opposed to transcendent (xviii). She argues that, whereas the Romantic tradition “recognizes language as an accurate roadmap for or a system of referring to situations and things in the real world,” the French tradition offers “ a model of the poem as an event on the page, in which language, while inevitably participating in a referential economy, is emphasized as a site of meaning in its own right” (xviii). Clearly the latter sounds more nuanced, and one would be hard pressed to find a statement of poetics naïve enough to describe language as “an accurate roadmap” to the real, so we are left to wonder at the reduction-ad-absurdum.

In addition, there is something both dodgy and trendy in the phrase “participating in a referential economy” with the word “economy” as jargon that conjures contemporary theoretical discourse about meaning as a production of power. To say language “participates in an economy” deftly avoids commitment with regard to the veracity, however partial, of language as referential. Roadmaps are models of the real with clear one-to-one relationships that avoid equivocation, but referentiality is a larger more complex phenomenon that allows for imperfection, suggestion, and intimation with regard to the pressure of reality. Without such pressure, no claim, including Swenson’s, can be true. So we might ask, is language referential in relation the real, or do we simply participate in an economy that operates as if it were? According to Swenson, the French tradition will assert no more than the fact that language has a referential currency minted by social transaction. While this is obviously true, Swenson’s rhetorical strategy brackets off the messiness of a real world beyond the pale of the language and focuses instead on a social context credited without qualification with the production of a sense of reality.

Equally shaky is Swenson’s notion that a non-Romantic tradition would by contrast emphasize language as “a site of meaning in its own right.” The phrase “in its own right” is blurry and untenable with regard to the phenomenon of meaning in language. Yes, poetry true to its vocation binds meaning inextricably to form and thus resists paraphrase, but in so far as there is such a thing as language and meaning, these things gesture beyond their own “site.” They are inherently relational and, more specifically, referential, imperfectly so, in ways that affirm more than simply some social consensus and self-referring economy. Language must have an outside, which, granted, makes it problematic. If we accept referential meaning as merely a production of social exchange with no so-called “real” other than the one we provisionally create, then language would have to cease to function as a language. Moreover our descriptions of language must be equally relativized and therefore neither true nor false. The banished ghost of the signified outside of language drains poetry of its consequence and necessity, and meaning gets conceived rather simplistically as identical with form, which it cannot be. The non-Romantic tradition, as conceived by Swenson, espouses an anti-metaphysical skepticism, while remaining unable to avoid language that is in some way metaphysical—words such as “self” that are neither cleansed of faith nor “an accurate roadmap” of the real.

Doubtless the urge to be modern would tempt any artist to remake not only the present but also the past. It is with some irony therefore that Swenson quotes Rimbaud’s famous statement “I is an other,” as some alternative to Romantic individualism when in fact the statement resonates strongly with the Romantic sense of the inner other. While Romantic individualism continues to influence popular culture, what Romantic writers make of the individual and subjectivity is less widely understood: namely, how the self appears bound up in an otherness that poetry is especially suited to explore. In spite of signs of individual pride on the part of Romantic writers, introspection leads less to a simple and stable reification of individual boundaries than a gaze at the sublime alterity of inner spaces. With regard to the sovereignty and stability of the individual self, Romantic writers embody an animating sense of contradiction, an affirmation of personal authority and defiance mixed with tremendous anxiety and excitement at the otherness so inseparable from identity and consciousness itself. The Romantics open for investigation the paradox that will continue to haunt post-war critical culture¬¬—that is, the self can never occupy the space of the other, nor can it extricate otherness from its nature.

Take Coleridge’s famous example in his poem “The Eolian Harp,” where the vast “intellectual breeze,” the transpersonal source and substance of thought, maintains a spiritual alterity without annihilating the nomenclature of personal self:

And what if all of animated nature

Be but organic Harps diversely fram’d,

That tremble into thought, as o’er them sweeps

Plastic and vast, one intellectual breeze,

At once the Soul of each, and God of all? (l. 44-48)

Unsettled by ecstasy and the oceanic surge of the inner divine, Coleridge feels the need to immediately qualify the dramatic sweep of his claim. Although the above metaphor embraces the connective principle that animates thought and thereby challenges the sense of self as reified, bounded, and exclusive, Coleridge’s next lines suggest that in his excitement lies ambition. He immediately registers a perceived need for humility in response, as if the ecstatic speculation were symptomatic of some manic flight of grandiosity, not a humbling or dissolving of the individual self, but an inflation of it:

But thy more serious eye a mild reproof

Darts, O beloved Woman! nor such thoughts

Dim and unhallow’d dost thou not reject,

And biddest me walk humbly with my God. (l. 49-52)

The poem’s argument suggests the divine, transpersonal quality of inner life poses a threat to the more traditional model where a theistic God walks in proximity to the intellect rather than illuminating its inner space. Aside from registering a violation of social convention, Coleridge’s resulting self-consciousness signals a danger to the necessary humility in one’s relation to the divine.

Humility is predicated on boundaries, but then so too is the ego’s sense of its autonomy and significance. What Coleridge dramatizes is the danger implicit in the idea of the inner divine. In the metaphysical language of depth psychology, the notion of the inner spiritual force tempts the ego to identify with the Self, the totality of the psyche, and fall victim to hubris. The dramatic arc of the poem illustrates the difficulty of maintaining a sense of the transpersonal within the personal—“the Soul of each, and God of all”—without suffering an inflation of the personal self as a defense against the threat of dissolution into the oceanic sublime. Somewhat paradoxically, one needs ego strength in order to avoid the anxiety that leads to ego-inflation. The fact that Coleridge does not call his vision an illusion is key. Even Coleridge’s fiancé, Sara, the woman of the poem, does not dismiss the contents of the vision, not explicitly. She offers only a look, not a language. One can only speculate that it is not the vision so much as the ego’s inflation in light of it that inspires repentance. The fact remains that a mysterious alterity does occupy the inner space of thought, and that mystery brings with it the anxieties of a self in recognition of its transpersonal inner life.

Language provides a primary means for poets to calm their anxieties, and yet the Romantics, as metaphysicians, remind us repeatedly of the limits of language as a defense against mystery, particularly in matters regarding just what consciousness is and how it works. That said, these very limits give birth to poems. What the Romantics bring to the cultural conversation is less a new way of writing a poem than a new way of conceiving the process endemic to imaginations of all eras. All poetry is metaphysical, all language for that matter, since words spring from wells of an otherness, both cultural and natural, beyond any individual’s witness or understanding. To speak we must see past the near at hand. We must transcend the materiality of form to give birth to meaning as, mysteriously, inextricably, embedded in that form. Meaning, however formal, is not form. Nor can such facts be relativized by a “referential economy.” The metaphysical hunger in language is fundamental to those who view poetry as a category larger than mere formal play, those who see in poetry’s imaginative means an ongoing commerce between self and other. Such is poetry’s great humanizing gift: to provoke us, lure us, to venture out by going in, to venture in by going out. The fruits of this are “romance” in the largest, oldest sense—wonder as not a form of escape but a means of transformation, not an assertion of our stability or sovereignty but an unsettling of the familiar, not a statement of self-importance but a watering of the known ground to glorify the roots that we can never see.

—Bruce Bond

Works Cited

Coleridge, William. “The Eolian Harp.” English Romantic Writers. David Perkins, Editor. NY: Harcourt,

Brace, & World, Inc., 1967.

Swenson, Cole. “Introduction.” American Hybrid. Cole Swenson and David St. John, Editors. NY: Norton,

2009.

Bruce Bond is the author of eight published books of poetry, most recently The Visible (LSU, 2012), Peal (Etruscan, 2009), and Blind Rain (Finalist, The Poet’s Prize, LSU, 2008). His tetralogy entitled Choir of the Wells will be released from Etruscan Press in 2013. His tenth book, The Other Sky (poems in collaboration with the painter Aron Wiesenfled, intro by Stephen Dunn), is also forthcoming from Etruscan. Presently he is a Regents Professor of English at the University of North Texas and Poetry Editor for American Literary Review.

February 4, 2013

The Many or The One

Contributor’s Marginalia: Paul Dickey on “The Belt” by Noah Kucij

As an instructor in Critical Reasoning and Philosophy (not English Comp or Literature), I may be the odd, ugly duck in this lake of 32. I teach my students that there are two ways that one fails to be clear. We are often vague and we are often ambiguous. Both are problematic in making one understood in a philosophical or logical argument, or even in day-to-day communication. They might worry whether their instructor is bald because just how bald does he have to be to be such, how much more hair would he need to have not to be so? Baldness seems vague. Although we seem to have some clue what it means, it does not clearly say what it means. But if I say that the blonde in the first row is hot, am I making an inappropriate sexual remark or am I concerned for my student’s comfort in the classroom? We know at least two things I might be meaning. Thus, it is ambiguous, and my keeping my job hinges on that the Dean understands which one I am saying.

I tell students to avoid both vagueness and ambiguity. Of course, I am speaking to my class in the context of prose not verse. As a poet, I myself go home from class and bend and stretch every ambiguity I can find to the breaking point. In the case of poetry, of course, we just as seriously strive to be clear, but the fine points of doing so may be different. We think at times even vagueness in verse might be good, even suggestive (well, perhaps, but be careful). And of course metaphor is ambiguous. After all, isn’t that the point of it?

So what counts as clarity in poetry? Ms. Marianne Moore suggested “imaginary gardens with real toads.” Mr. Noah Kucij’s “The Belt” in the latest 32 Poems points out to us the Walmart belt inching forward with “what we love.” Of course, Mr Kucij avoids vagueness by identifying quite accessibly what is on the belt: Depends, Ensure, Lysol. But even more to the point here, the ambiguity itself is clarity. It is an ambiguity where two sides of the equation must exist at the same time, not be resolved into the one. Mr. Kucij’s ambiguity is one where both meanings are fully relevant, necessary, engaged, enriching. We cannot speak only of one meaning without minimizing the meaning, not as in my earlier example of the “hot blonde,” where dismissing one meaning clarifies the meaning.

Of course, Mr. Kucij’s poem (and yes, my own in this issue) is not clear or understandable in terms of what I demand of my student’s logical arguments. Though not vague, “The Belt” is quite ambiguous. Here, words do and should mean more than one thing, although they mean exactly what they mean (not vague):

in Walmart, celestial fixtures

never blink. At home, the dog

or:

down with care. We merge into

a single lane, we slap our stories

on the belt,

or finally, even

putting bread on credit, double-

bagging bleach and ketchup, trying

to keep what we love alive.

Mr. Kucij achieves clarity through ambiguity by providing us a necessity (a deductive logic of sorts) of two different worlds we know well, and they are colliding in a way we always “knew” they would but at the same time also never suspected. A paradox, but what makes Mr. Kucij’s poem clear is that in it we lose the distracting, confusing sense that we could do without either: 1) the belt moving forward, not stopping, even as we burden it with new items, or 2) our love. No denying it. We live in this dualistic world. Nothing can be clearer, as it were.

So, as you might also guess, I am partial to poetry that is not (to use one very frequently unclear word) “subjective.” I consider poetry subjective (sadly, my own quite often), if image, craft, etc, are there because the poet for his or her reasons chose to put them there and then must work for the poem to justify them, to see them. This is not always bad poetry of course, but subjectivity, besides its other risks, often becomes unclear.

In “The Belt” the images are there because (sorry, there seems no other way to say it) they are there, they somehow have to be there. As such, these images/this language may even have to risk banality in places (which for the most part, I would argue Mr. Kucij avoids). That is, I like poetry that proves itself (which of course is an oxymoron). But, yes, I’ll say it again, this poem proves itself. It is an oxymoron which, I believe, can enlighten us on much verse today, and in particular, enlightens Mr. Kucij’s poem.

The poem, of course, is no syllogism recognizable by Aristotle:

Premise One: The celestial fixtures never blink.

Premise Two: We slap our stories onto the belt.

__________________

Conclusion: I want to kiss the haggard cashier older than my mother.

But if this is not a valid poetic argument, I don’t know what is. In Mr. Kucij’s poem, from premises, his conclusion inevitably follows. It is true, that is, in all of Leibniz’s possible worlds.

—Paul Dickey

Paul Dickey’s first full-length book of poetry, They Say This is How Death Came Into the World, was published by Mayapple Press in January, 2011. A new book, Wires Over the Homeplace, will be published by Pinyon Publishing this fall. Besides 32 Poems, his poetry, fiction, and creative non-fiction has appeared recently or is forthcoming in The Bellevue Literary Review, Pleiades, Prairie Schooner, The Hampden-Sydney Poetry Review, Memoir (and), and many other journals. Over the past five years, Dickey has been a frequent contributor to the acclaimed journal on prose poetry Sentence and appears in their textbook anthology, An Introduction to the Prose Poem from Firewheel Editions. In addition to his literary work, Dickey also writes plays and teaches philosophy at Metropolitan Community College in Omaha, Nebraska.

Paul Dickey’s first full-length book of poetry, They Say This is How Death Came Into the World, was published by Mayapple Press in January, 2011. A new book, Wires Over the Homeplace, will be published by Pinyon Publishing this fall. Besides 32 Poems, his poetry, fiction, and creative non-fiction has appeared recently or is forthcoming in The Bellevue Literary Review, Pleiades, Prairie Schooner, The Hampden-Sydney Poetry Review, Memoir (and), and many other journals. Over the past five years, Dickey has been a frequent contributor to the acclaimed journal on prose poetry Sentence and appears in their textbook anthology, An Introduction to the Prose Poem from Firewheel Editions. In addition to his literary work, Dickey also writes plays and teaches philosophy at Metropolitan Community College in Omaha, Nebraska.

February 1, 2013

Weekly Prose Feature: “My Abilities Are Ridiculous: On Poetry and the Occasional Crisis of Faith” by Emilia Phillips

R. Shalom spoke fluent English, but he hadn’t a clue what I meant when I said I write poetry. My husband and I were taking the sixty-minute ferry from Puntarenas to Paquera, Costa Rica when the young Israeli with oil-slick Ray-Bans and a fishing rod instigated conversation. I’d been embarrassed to tell him what I did, as he put it, “for a living.” I lived off poetry only in the metaphorical sense but not in the pay-the-bills sense, and I worried about throwing a metaphor at someone whose first language wasn’t my own. My husband, however, offered that I was a poet; I corrected, “I write poetry.”

R. shrugged. “I don’t know what you mean—What is poetry?”

I knew then, and there, I didn’t know either.

*

At the time, I was an MFA student, but no one had ever told me what poetry is. Some say it’s like pornography or love—you know it when you see it. I won’t surrender you to the dictionary; the entries are stultifying. (What the hell does “a literary genre in which special intensity is given to the expression of feelings and rhythms by the use of a distinctive style or rhythm” actually tell you?”) The etymology, as we know, blames the Greeks: poiein, “to create.”

Try to remember the first moment in which you understood what was meant by the word poetry. I can’t. Did my parents describe Dr. Seuss as poetry? Did a primary school teacher ask me to write a poem? My first conception of poetry was that it rhymed. But when did I learn rhyme?

“It’s writing,” I said, miming a scribble. “In lines.”

“Oh, lines…” R. Shalom replied, lifting his rod, and, more assured, “For bait.” He’d been telling us about Pacific marine life and school migration since we boarded. Context assumed reason.

*

A former anthropology professor tells a story about taking a group of students to China. He gave them one rule: They were not allowed to ask what they were eating until after they ate. One young man gobbled down a plate of gelatinous cubes, thinking it a savory pudding or gelatin snack. After leaving the restaurant, however, the professor identified the dish as congealed pig’s blood; the student, suddenly self-aware, vomited in the gutter.

*

Roethke wrote that poetry’s basis is sensation. Aristotle said that poetry is a mode of imitation. The two ideas aren’t far apart. Isn’t an imitation inherently rooted in sensation, the senses?

Recently I gave my advanced poetry students a handout of “encounter” poems, including James Wright’s “Blessing,” Bishop’s “Moose,” and Oppen’s “Psalm.” The ways in which the speakers of these poems encounter other beings—with a cocktail of adrenaline, prejudices, curiosity, and, sometimes, fear—mimics how readers approach a poem. The act of reading a poem tests the limits of our empathy. Though we may be able to postulate about the choices the poet made in the poem, we can never fully know a poem, the way we can never fully know an animal or a person.

My mother-in-law, in order to appeal to my interests, bought me a canvas print of a wine bottle. The caption, a scrawl: Fine Wine is like Poetry. “It’s poetry in motion,” Thomas Dolby sang. Bob Dylan is a poet. A Facebook post: Why isn’t Leonard Cohen included in the 20th-century American Poets stamps? The way the basketball player moves on the court is pure poetry. Target framed a coupon booklet as “Haikupons”:

date night has arrived

cheeks want a colorful boost

I can see you blush

My high school boyfriend was the first person I knew that wrote poetry. All of his lines ended in ellipses. They weren’t so much endstopped as decrescendoed, giving each short lyric a kind of wa-wa effect. I played guitar so, to me, anything that rhymed was best served by being set to music. But he got me thinking: Maybe I could write a poem.

When my AP English teacher gave us an unattributed poem, I knew, after months with my Perrine’s Literature, that it was John Donne’s. I couldn’t say why, and though the teacher might’ve thought it a lucky guess, I attest I knew.

*

When R. Shalom finally said, “Oh, you write about your emotions,” I gave up. What is poetry? I had no way to say. I felt like a phony then. I’d been gobbling it up by the plateful, not knowing what it was. How could I be a poet?

I once had a student who responded to most anything I did with “You’re such a poet.” I wore sandals to class one day. Poet. I mentioned Frank Zappa. Poet. I talked about traveling in Europe. Poet. I ate quinoa. Poet. I mentioned there would be wine at a reading I wanted them to attend. Poet. I like jazz and diagrams, walking in cemeteries and taking photos. Poet. Poet. Poet. Poet.

For a long time I wondered when I could call myself a poet. Was it after I’d taken poetry classes for a while? After I published my first poem? After I enrolled in an MFA program? After I published my first book?

My grandmother told some friends and distant relatives that I’m a journalist. I don’t blame her.

*

When my half brother, my only sibling, died of complications from a rare genetic disorder last year, poetry suffered with me. It trailed behind me like a stray dog I fed once a long time ago. I couldn’t write, I couldn’t read, and didn’t want to, didn’t need to.

Oppen confessed, “My abilities / Are ridiculous.” I felt ridiculous telling the Pediatric ICU nurses what I do. They didn’t ask me about poetry but their looks were as polite and bemused as R. Shalom’s. I stopped answering altogether or said I worked for a magazine. I changed the subject, told them that my husband was a physical therapy assistant—something in their field, their line. Anything else, anything but Poet. Poet. Poet.

A month after the funeral, I was scheduled for a month-long residency at the Vermont Studio Center. I almost turned it down, but family insisted I go. Some days, I got a little work done—a book review, a few revisions to my manuscript—but others I couldn’t bear to do anything but read Stevens and cry. (Who cries over Stevens?)

Perhaps it was this passage that set the tone, from “Large Red Man Reading”:

There were ghosts that returned to earth to hear his phrases,

As he sat there reading, aloud, the great blue tabulae.

They were those from the wilderness of stars that had expected

more.

There were those that returned to hear him read from the poem of

life,

Of the pans above the stove, the pots on the tables, the tulips among

them.

There were those that would have wept to step barefoot into reality,

That would have wept and been happy, have shivered in the frost

And cried out to feel it again.

I imagined, in my studio, as I whispered over a book, I was reading aloud to my brother’s ghost who hovered just outside the window, who lived in the river down below, who was covered in mud or mist, was as large as the room or small as a wasp that bumped against the glass. I dreamed he ran past me (he couldn’t walk when he was alive). I know that if I could catch him, he would be returned to life. But he’s so fast, and I worry that I won’t recognize him if I do catch up, that I’ve never known him, never seen him, that he won’t recognize me—my face as a stranger’s, without purpose. Formless. I can never touch him, I couldn’t touch him. I have no way.

I taped a Ruth Stone line on my studio door: “The Muse is depressed.”

Though I am grateful for the opportunity, for the people I met, my residency in hindsight feels largely traumatic. Halfway through the month, I called my husband and told him I was in emotional exile. Poetry made me vulnerable, made me open to grief. I would give it up and go to med school, be a geneticist. Move on. Live instead of dwell.

But then I started to think about DNA as a kind of poem; each chromosomal line, each strand of information—what a form, the helix!—and I fell into a deeper reverie.

*

(A friend, after reading about my affinity for the helix, wrote: “Poet.”)

*

Flaubert’s The Temptation of Saint Anthony begins with Anthony’s doubt about his chosen lot, his exile in the Nitrian desert:

A happy life this indeed!—bending palm-branches in the fire to make shepherds’ crooks fashioning baskets, stitching mats together—and then exchanging these things with the Nomads for bread which breaks one’s teeth! Ah! woe, woe is me! will this never end? Surely death were preferable! I can endure it no more! Enough! enough!

Of course, this doubt (and what is doubt but questioning?) makes Anthony vulnerable to the numerous temptations with which Lucifer hounds him. The Queen of Sheba, the logic of wise men, wealth, Death and Lust, strange beasts. But Anthony’s greatest grief is the “fountain of mercy” he once felt “pouring from the height of heaven,” this inspiration and charge, “now dried up.”

Unlike Anthony, whose beliefs insist an insular and blind acceptance of doctrine, doubt makes poets; it causes them to engage in one of the most important endeavors of good poetry: the question.

*

Mary Ruefle writes that “The origins of poems, prayers, and letters all have this in common: urgency.”

But Roethke counters: “raptures are hard to sustain.”

Zbigniew Herbert says that the most pure language is that of “sweet dread.”

And Dickinson: “When I hoped I feared.”

“[T]he sleepy diarrhea of fear,” Alan Dugan calls it.

Neruda: “Is it bad to live without a hell: / aren’t we able to reconstruct it?”

David Ferry: “Somebody’s got to tell me the truth some day. / And if somebody doesn’t tell me the truth I’ll tell it.”

“Though I am everywhere just now there is nobody here but me,” says Apollinaire.

And Ellen Bryant Voigt: “Nothing is learned / by turning away.”

*

Months after Nick’s death, poetry redeemed itself to me, as it always does, through a W.S. Graham poem that I find still mysterious and coded even as it plays to my own circumstances. “Definition of My Brother” begins:

Each other we meet but live grief rises early

By far the ghost and surest of all the sea

Making way to within me.

And later, with more momentum:

One another I leave into Eden with. I commit

The grave. Poverty takes over where we two meet.

Time talks over the fair boy. His hot heartbeat

Beats joy back over the knellringing till defeat.

Graham, an English poet and fisherman, has a kind of ouroboran syntax here, each unit of the sentence seems to move forward, but then, in a quick turn, it returns to its head, as in later lines where the speakers promises to

ship the mad nights to bright benefits

To that seastrolling voice in waves and states

Not mine but what one another contrary creates.

What one another contrary creates. How a thing creates—or at least implies—its negative. I’m not sure what happens in the poem, not exactly. I’ve spent hours with it, reading and rereading. I sent copies to my family, to friends. I typed it up and hung it beside my desk. Given, however, the unexpectedness of my brother’s death, the unanswered questions, the elliptical Graham poem responds to my questions by causing me to ask more questions. Combat doubt with doubt.

If certainty were poetry’s aim then we should all be called journalists. But the journalists now ask, Is poetry dead?

*

What is poetry?

When I hoped I feared my abilities are ridiculous. The Muse is depressed, but I’ll ship the mad nights to bright benefits. There were those that would have wept to step barefoot into reality, that would have wept and been happy, have shivered in the frost, and cried out to feel it again. Nothing is learned by turning away. Pure the language of sweet dread. Somebody’s got to tell me the truth some day. Be this my text, my sermon to mine own.

—Emilia Phillips

Emilia Phillips is the author of Signaletics (University of Akron Press, 2013) and two chapbooks including Bestiary of Gall (Sundress Publications, 2013). She has held fellowships from U.S. Poets in Mexico and Vermont Studio Center; she received the 2012 Poetry Prize from The Journal and Second Place in Narrative’s 2012 30 Below Contest. Her poetry appears in AGNI, Hayden’s Ferry Review, The Kenyon Review, The Paris-American, and elsewhere. She is an instructor of creative writing at Virginia Commonwealth University, the associate literary editor of Blackbird, a partner with C&R Press, and the prose editor for 32 Poems. She lives in Richmond, Virginia.

Each Friday we will publish a new essay, review, or interview for the 32 Poems Weekly Prose Feature, edited by Emilia Phillips. If you have any questions or comments about the series, please contact Emilia at emiliaphillips@32poems.com.

January 30, 2013

The Surreal and the Small

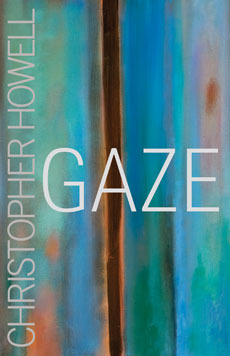

Review of Gaze by Christopher Howell (Milkweed Editions, 2012)

Christopher Howell’s tenth collection of poems, Gaze, bears the ghostly structure of a fugue: certain elements recur in these poems—notably memory and the past, a mother’s shade, paradoxes, crows, unanswerable questions, the afterlife and its possibility, small town bars and small town lives—these elements return and are changed, faded, transfigured or transformed.

These poems do not shrink from surreality (‘The Circular Saw Children Confess Their Joy’; ‘The Refusal to Count Beyond Seven’: “There were seven crows inside her / gibbering and flapping, emitting / the occasional squawk”, a poem that seems brushed by the hand of Stevens) or beauty. Howell has a real gift for unearthing an image. More importantly, he juxtaposes his most poignant images with darker or stranger ones (“The dark branch breaks under a crow / that has been trying to break it. / My daughter’s face / fades in and out of the clouds gathered…”), or manages to undercut or sideswipe them with a humor that edges each poem—a quiet humor, sometimes gritty—so that the images become more resonant, more closely tied to the animating tension of the poem.

These poems do not shrink from surreality (‘The Circular Saw Children Confess Their Joy’; ‘The Refusal to Count Beyond Seven’: “There were seven crows inside her / gibbering and flapping, emitting / the occasional squawk”, a poem that seems brushed by the hand of Stevens) or beauty. Howell has a real gift for unearthing an image. More importantly, he juxtaposes his most poignant images with darker or stranger ones (“The dark branch breaks under a crow / that has been trying to break it. / My daughter’s face / fades in and out of the clouds gathered…”), or manages to undercut or sideswipe them with a humor that edges each poem—a quiet humor, sometimes gritty—so that the images become more resonant, more closely tied to the animating tension of the poem.

In ‘The Paradox of Place,’ a red kimono in an empty house becomes an emblem of loss and memory, after “the moon comes home / with nothing in its mouth and no one near,” after the speaker traces the “intricate figure / of absence / to the beloved dead,” and after the speaker traces the course of his life, which is a “house that runs on empty / red kimonos, wild / roses where there used to be a door.” In this final movement, Howell manages a piece of alchemy, an imagistic match that happens when the speaker’s past and present collide, as the red kimonos become these wild roses over the empty doorway, in a place the speaker is and is not. These are beautiful crow-lit lyric poems singed with memory, delivered in an off-hand minor chord, touched by the surreal and the small, that manages to distill loss and still deliver a fierce joy.

—Mark Wagenaar

Mark Wagenaar is the author of Voodoo Inverso, 2012 winner of the Pollak Prize. Recent appear of are forthcoming in Tin House, Beloit Poetry Journal, Southeast Review, & Southern Indiana Review.

January 29, 2013

Old Flame: From the First Ten Years of 32 Poems Magazine

Ten Years of 32 Poems in a single book. Be the envy of your neighbors who read books. Outcool the cool kids. Heat up the hotties. Inspire children and birds to acts of kindness. Order this now. Obey. Free shipping and 20% off. And for the sake of poetry, share the word!

Run your eyes over the contents: you’re not going find a better gathering.

Contents:

Introduction — Deborah Ager, Bill Beverly and John Poch

Believing Anagrams — Kelli Russell Agodon

Verge — Melanie Almeder

Childless — Amanda Auchter

Experienced Worker, Employment Wanted — Curtis Bauer

Come On — Evan Beaty

When at a Certain Party in New York City — Erin Belieu

The Fatherless Room — Paula Bohince

The Missing Link — Bruce Bond

Marion Crane — Kim Bridgford

Exercitia Spiritualia. — Geoffrey Brock

First Astronomy Globe — Stephen Burt

Why We Love Our Dogs — Amy M. Clark

Love Letter 41 — Esvie Coemish

The Pencil — Billy Collins

Poetry Doesn’t Need You — Ken Cormier

The Match — Chad Davidson

Men — Lydia Davis

The First Age of a World Economy. — Carolina Ebeid

The Lord’s Prayer — Gregory Fraser

The Problem with Describing Night — Bernadette Geyer

Dankness and Cathedrals — Lohren Green

Look at the Pretty Clouds — Austin Hummell

Canapès — John Jenkinson

When the Rider is Truth — Carrie Jerrell

Parallel — Marci Rae Johnson

Love and the National Defense — Holly Karapetkova

The Wolf — Brigit Pegeen Kelly

The Previews — David Kirby

At the Loom — Jacqueline Kolosov

Hometown — William Logan

Tastebud Sonzal — Amit Majmudar

American Apparel — Randall Mann

Ice-Tea — Kevin McFadden

Come Home Late, Rise up Sleepless, or Just Act Troubled — Erika Meitner

Phobia — Jennifer Militello

St. Benedict — Daniel Nester

Two Egg, Florida — Aimee Nezhukumatathil

The Place above the River — Kate Northrop

The Dead End — Dan O’Brien

As a Damper Quells a Struck String — Eric Pankey

So — Anne Panning

Lower Limit Song, The Chord — Jeffrey Pethybridge

Iceland — Dan Pinkerton

Airplane Downed, in the Winter Pines — Kevin Prufer

No Mark — Matthew Roth

Palm Heel — Natalie Shapero

Tyrannosaurus Sex — Eric Smith

Mercatale Hope — Maxwell Snyder

After John Donne’s “To His Mistress Going to Bed” — Lisa Russ Spaar

Ultrasound — A. E. Stallings

Matchbox — Maura Stanton

Want Me — Melissa Stein

What I Know for Sure. — Alexandra Teague

Fabulous Ones — Jeffrey Thomson

Back Then — Eric Torgersen

Tenth Flight — D. H. Tracy

Piñata — Laura Van Prooyen

Toilet Flowers — Adam Vines

Justice — William Wenthe

Rock — Greg Williamson

The Darker Sooner. — Catherine Wing

Clotheshorse — Terri Witek

What’s Wrong With You — George Witte

Trying Not to Cry Before Dinner — Josephine Yu

Commentary

Seriously, buy your copy now.

January 28, 2013

The Consolation of Seeing Clearly

Contributor’s Marginalia: Carrie Shipers on “Winter Inlet Arrangement” by Hastings Hensel

This morning, in gray central Wisconsin, we have subzero temperatures and a howling wind, but nothing outside my door seems to me as chilling—or as lovely—as Hastings Hensel’s poem, “Winter Inlet Arrangement.”

The sonnet’s opening line, “Everything in pain,” initially may seem like melodrama or exaggeration, but the lines that follow are all the more striking for their matter-of-fact tone as Hensel leads us through a landscape that includes “a bloated ribcage of marsh grass” and “rock jetties . . . / assaulted by sea-spray, without objection.” While the typical Petrarchan sonnet teaches us to expect that the question raised in the first eight lines will be resolved in the final six, Hensel’s poem resists such tidy closure. To the octave’s initial “Everything in pain,” the first line of the sestet replies, “But nothing heals. Everything in more pain,” a bleak statement followed by further inventory of a world in which the water is “starved” and even the tide is screaming.

Morning Salisbury Beach, Alfred Thomas Bricher

Among the many things I admire about this poem is that although the scene being described is undeniably bleak, it is also quite active—it’s just that all of the activity is either harmful or a reaction to being harmed. Even the poem’s brief—but necessary—moment of humor, in which we see “the stone crab / waving its heavy claw for help,” underscores the poem’s sense of desolation, while the assurance with which these lines are constructed insists that Nature and those who seek to profit from it, “the bullish oystermen kneeling in the low tide,” are being depicted exactly as they are.

But are they, really? As I reread, I find myself as drawn to what the poem withholds as to what it reveals. Surely we can assume a human speaker, a human consciousness, responsible for the observations in the poem, and surely there’s a reason that human speaker sees only pain in what otherwise might be an ordinary, even uplifting, view of harbor and sea. Part of the poem’s power comes from its sense of restraint (not to be confused with secrecy): we see the result of the speaker’s emotional state but not its cause, and the poem is all the more powerful because this is so.

Nor does Hensel’s poem put much emphasis on solace, although I’d argue that the poem does hint at the consolation of seeing clearly, a quality that reminds me very much of Elizabeth Bishop’s work. But unlike the speakers in Bishop’s poems, who so often are compelled to re-see, to re-phrase and re-describe in order to be as accurate as possible, Hensel’s speaker has no need to re-consider or re-word: everything already has been said as concisely and clearly as possible.

The world Hensel depicts in this poem is not one I much want to inhabit. And yet—what pleasure is to be had from Hensel’s tense, densely packed lines, the sensual pleasure of forming syllables, spitting out the shards of consonants that embody the poem’s stern and lovely chill. If you haven’t already, you must say out loud, as often as possible, the catalogue that opens the poem: “scar lines and scrapes / of gray cloud, gull-scream, crushed shells / slicing the tin sheen of the pluff mud bank.” Everything may be in pain, but rarely does the world suffer as beautifully as in this poem.

—Carrie Shipers

Carrie Shipers’s poems have appeared in Connecticut Review, Crab Orchard Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Laurel Review, New England Review, North American Review, and other journals. She is the author of two chapbooks, Ghost-Writing (Pudding House, 2007) and Rescue Conditions (Slipstream, 2008), and a full-length collection, Ordinary Mourning (ABZ, 2010). She currently teaches English at UW-Marshfield/Wood County in Marshfield, Wisconsin. Her poem, “John Wayne,” appeared with Hastings Hensel’s “Winter Inlet Arrangement” in 32 Poems 10.2.

Carrie Shipers’s poems have appeared in Connecticut Review, Crab Orchard Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Laurel Review, New England Review, North American Review, and other journals. She is the author of two chapbooks, Ghost-Writing (Pudding House, 2007) and Rescue Conditions (Slipstream, 2008), and a full-length collection, Ordinary Mourning (ABZ, 2010). She currently teaches English at UW-Marshfield/Wood County in Marshfield, Wisconsin. Her poem, “John Wayne,” appeared with Hastings Hensel’s “Winter Inlet Arrangement” in 32 Poems 10.2.

January 21, 2013

All That Was There and Only

Contributor’s Marginalia: Carol Light on “Bang” by Hannah Sanghee Park

If “Bang” is an indicator of the Ferris wheels and Gravitrons of thought in this poet’s imagination, then I would love to spend a vacation twirling through the carnival of Hannah Sanghee Park’s mind. More minstrel than expostulator, the poet’s tilt-a-whirl logic is dizzying. A pirouetting ballerina uses a spotting technique to keep balance while spinning, and spotting the patterns and formal structures of the poem steadied me through its linguistic dance. Each of the couplets introduces a rhyme at the end of the first line that is immediately and imaginatively bisected in the line that follows.

“Just what they said about the river:

rift and ever.”

I admire this intuitive mind, while my faithful servant follows behind, lugging a dictionary. My inner parser, having tea with the OED, snakes along her river toward the Latin riparia, to the bank beside the channel, to rive, to render and tear, and eventually to the euphemistic boundary between life and death, hence “rift and ever.” The poem both begins and ends in the first two lines. But it continues…

“And nothing was left for the ether

there either.”

The ethereal being, for me, a favorite realm, I applaud the possibilities summoned into being! Latin æther, imported from Greek, shares a root with kindle, burn, shine, and fair weather. The clear sky above the clouds, the cosmological element filling all space beyond the sphere of the moon, divine air breathed by the gods, the luminiferous medium through which the waves of light are propagated, not to mention a solvent possessing anesthetizing properties.

Creation of the Sun and Moon, Michaelangelo

Uncoupling happens in these couplets. The poet’s method is to fabricate a compound history in every second line for the end word of every first line. A sort of associative etymology emerges: mature becomes matter and nature. Scripture becomes scribe and capture. Neither element is half of what it was before. Park’s literary fission liberates energy. If you prefer metaphysics to physics, then perhaps Genesis: the poet is a god separating the heavens from the earth.

“Bang,” recalling Big Bang, flirts with the rhetoric of a creation story that is as religious as it is astronomical. Like the universe, the poem accelerates as it expands. The couplets appear both self-contained and cumulative. I marvel at how the poet builds and balances an elusive narrative, and breaks it in every second line. Overriding all is a sense of heartbreak and loss, of separation, until the empty sky is bleached cleanly clear, evenly, when what is left of the world is what we covet.

Cosmogony, cosmology, cosmatesque. I love to follow the patterns through the lines, but the poem isn’t simply a divine or decorative geometry. Is it a creation story? A love story? A promise broken, line after line? As in any good theory, procreation has its part to play. And Park’s wordplay is a fuse lit at the end. What fireworks lurk inside covet? Cupidity’s hot breath pants under that coverlet, and an invitation to begin again follows the poem’s penultimate conjunction: “Come over et—“

—Carol Light

Carol Light’s first book, Heaven from Steam, will be published in 2013 by Able Muse Press. Her poems have appeared in Narrative Magazine, Poetry Northwest, American Life in Poetry, Literary Bohemian, and elsewhere. She lives with her family in Port Townsend, Washington. Her poem, “Downdraft,” appeared with Hannah Sanghee Park’s “Bang” in 32 Poems 10.2.

Carol Light’s first book, Heaven from Steam, will be published in 2013 by Able Muse Press. Her poems have appeared in Narrative Magazine, Poetry Northwest, American Life in Poetry, Literary Bohemian, and elsewhere. She lives with her family in Port Townsend, Washington. Her poem, “Downdraft,” appeared with Hannah Sanghee Park’s “Bang” in 32 Poems 10.2.

January 14, 2013

Lover and Devil

Contributor’s Marginalia: Kathleen Winter on “Winchester .351 High-Power Self-Loading Rifle” by Alexandra Teague

I read, admired, and chose to write about Alexandra Teague’s sonnet early in December, before the Dec. 17, 2012, Newtown, Connecticut school massacre. I can’t read this poem now without considering the mass killings by gunmen last year, and our national debate over gun control. And also thinking about the different ways journalists and poets are able to take on issues of deep communal importance.

Of course Teague’s poem, written earlier, doesn’t address December’s events, but it does speak to the fundamental issue of people using guns to take lives. Powerfully, movingly, the poem questions a hunter’s use of the Winchester rifle to destroy a cougar. Teague shapes her critique with the verbal subtlety and sophisticated emotional insights that poets and poetry make time for. The sonnet’s gentle rhyming vowel sounds (love/rush, roots/lose) and rhymes of last letters (handsomest/scent, devil/recoil) keep readers focused on the sonnet’s imagery and syntactically unfolding reasoning, rather than on its Shakespearian form.

Tiger, Lion, and Leopard Hunt, Peter Paul Rubens

The epigraph from Calvino effectively signals the poem’s critical view of a hunter who can only show love for living things by shooting them. The tone in the epigraph from Calvino is sharper than the poem’s delicate irony. Teague achieves a calmly ironic perspective by adopting Calvino’s claim that the hunter is a lover, and adding her own claim that the cougar is a lover as well. The poem’s overriding metaphor is the romantic relationship charged by passion and danger. To bring in the language of romance, Teague weaves in text found in a 1909 advertisement: “. . . the lightest, strongest, handsomest/repeater ever made….” The poet anthropomorphizes the cougar and makes him sympathetic by portraying him as a lover who wants what the speaker and reader also are assumed to desire: “A love/ that ‘can shoot through steel.’ ” The cougar/lover is presumed willing to “lose/this skin for an instant of lightning.” The hunter is both lover and devil, but the speaker’s perspective, and therefore most likely the reader’s, is aligned with the cougar.

The closing couplet is gracefully restrained in its music, but the poet’s choice to close the poem with the word “recoils” suggests an emotional response to the hunter/lover who, at the moment the poem ends, kills the cougar we’ve just been admiring for being passionate, aware, and “unflinching” as he waits. I’m delighted by how Teague’s poem modernizes the conventions of 16th century love poetry, adding found language and social critique to the consistent challenges of writing in a fresh way about the dangers and compulsions of desire.

—Kathleen Winter

Kathleen Winter’s first book, Nostalgia for the Criminal Past, won the Antivenom Poetry Prize and was published by Elixir Press in 2012. Her poems are forthcoming in Tin House, Sentence, New American Writing, and Studio (U.K.). Her work has appeared in 32 Poems, AGNI, The New Republic, FIELD, Memorious, VOLT, Barrow Street, Anti- and The Cincinnati Review. Kathleen grew up in Texas and graduated from the MFA program at Arizona State in 2011. She teaches at the University of San Francisco.

Kathleen Winter’s first book, Nostalgia for the Criminal Past, won the Antivenom Poetry Prize and was published by Elixir Press in 2012. Her poems are forthcoming in Tin House, Sentence, New American Writing, and Studio (U.K.). Her work has appeared in 32 Poems, AGNI, The New Republic, FIELD, Memorious, VOLT, Barrow Street, Anti- and The Cincinnati Review. Kathleen grew up in Texas and graduated from the MFA program at Arizona State in 2011. She teaches at the University of San Francisco.

January 7, 2013

The Black of Noir

Contributor’s Marginalia: Peter Kline on “Noir” by Kathleen Winter

Interrupting guilty silences, Noir is the heart’s black thud in the chest of every human being. It is the mourner’s tabulations, the teacher’s contempt, the brother’s conniving. It is the bridegroom’s furtive leer, the hesitation in the host’s welcome, the penitent’s wink. Seen through its mirrored smoke-colored glasses, a common kindness is transformed to a cheap come-on, or else an evolutionary glitch. Noir leaves a greasy fingermark in grandmother’s sugar bowl.

We think of ardor as irony’s enemy, but Noir’s sense of irony is passionate. Today’s predominant irony is one of mixed discourse, akin to sarcasm, in which we do not mean all that we say, undermining passion by turning our language against itself. Noir’s irony is more cosmic. It holds up the prevailing archetypes of good and evil, punishment and reward, so flattering to the society that cherishes them, and mocks them for their flimsiness and vanity by calling attention to their unfulfilled promises. The alderman pumps poison into the well to pay off a bet; the judge takes a tidy commission from the juvenile prison; the hero demands a piece of the action, or else; the doe-eyed daughter pulls out a snubnose revolver from her garter.

Noir may be disenchanted with the world, but it is never disenchanted with language. One of the hallmarks of Noir is its delight in the cryptic ingenuity of its vocabulary. The black of Noir exists as a shadowy alternate to the world of full color; this different way of being demands a different way of speaking, one that allows its furtive denizens to recognize one another and communicate. Noir names a secret world.

Eve Offering the Apple, The Elder Lucas Cranach

Adam, too, was a namer, one of the many reasons I found Kathleen Winter’s application of Noir to the Garden of Eden so delightful and unexpectedly apropos. In Winter’s “Noir” it is not Adam who is doing the speaking, however; the poem gives Eve a chance to defend her wayward behavior, and she shows herself to be serpent-subtle, a linguist as masterful as Adam. Her words immediately impose her authority (even as she’s trying to wriggle out from under her deed), not just naming the animals but also claiming them for her side:

All the animals in the garden

knew the score: Rat knew,

Gnu knew, even Gnat

knew Snake was telling me

what to do.

True to the spirit of Noir, this Eve seems never to have been innocent. The music and slangy eloquence of her defense only serve to emphasize her compromised moral position. It is as if, with the bite of the apple, she has gained not just knowledge of good and evil but a cynical understanding of her role as one of the great patsies in the history of the patriarchal world. She’s resigned; she’s not trying to make a stink about it. But that doesn’t mean she thinks she got a square deal. With a flicker of rage and a shimmying coo she asks, blinking, “what could I do?” and we sympathize. The mother of mankind is no jingle-brained frail.

—Peter Kline

Peter Kline’s poetry has appeared in Ploughshares, Tin House, Poetry, Antioch Review, and other journals, and has been anthologized twice in the Best New Poets series and online at From the Fishouse. He is the recipient of a 2008-2010 Wallace Stegner Fellowship and the 2010 Morton Marr Poetry Prize from Southwest Review. His first collection of poems, Deviants, is forthcoming in the fall of 2013 from Stephen F. Austin State University Press.

Peter Kline’s poetry has appeared in Ploughshares, Tin House, Poetry, Antioch Review, and other journals, and has been anthologized twice in the Best New Poets series and online at From the Fishouse. He is the recipient of a 2008-2010 Wallace Stegner Fellowship and the 2010 Morton Marr Poetry Prize from Southwest Review. His first collection of poems, Deviants, is forthcoming in the fall of 2013 from Stephen F. Austin State University Press.