Deborah Ager's Blog, page 11

August 10, 2012

From the Archives: “Spring Recital, Beethoven Club, Memphis, Tenn.” by Bobby C. Rogers

This week we’ve been rereading Bobby C. Rogers’ Paper Anniversary (U of Pittsburgh P, 2010) and letting that long line of his bowl us over. Rogers is professor of English at Union University in Jackson, Tennessee. His poems have appeared in the Southern Review, the Georgia Review, Image, Shenandoah, Puerto del Sol, and numerous other magazines. He is also the recipient of the Greensboro Review Literary Prize in Poetry. His ”Spring Recital” was first published in the Fall 2009 issue (7.2) of 32 Poems.

This week we’ve been rereading Bobby C. Rogers’ Paper Anniversary (U of Pittsburgh P, 2010) and letting that long line of his bowl us over. Rogers is professor of English at Union University in Jackson, Tennessee. His poems have appeared in the Southern Review, the Georgia Review, Image, Shenandoah, Puerto del Sol, and numerous other magazines. He is also the recipient of the Greensboro Review Literary Prize in Poetry. His ”Spring Recital” was first published in the Fall 2009 issue (7.2) of 32 Poems.

Spring Recital, Beethoven Club, Memphis, Tenn.

After all the practice, the children in turn mount the two steps of the riser,

jaws set, their Sunday clothes,

new for Easter or just new, making a detectable wrinkling sound as they

compose themselves at the keyboard and unfold

their repertoire books to the marked page, take a deep breath and strike the

opening notes of undanceable mazurkas

and poorly studied études. Hard to add up all that’s been learned just from

looking at a room like this, most of it

having to do with fear. The first week in May and the air conditioner already

strains, the kids sweating at the Baldwin grand—

of the pair of pianos, the one with the easier action and bright tone. From

our place in the crooked rows of folding chairs, we just hope

the pictures turn out. And then there it is, the architecture of a Bach

invention, the lines of development,

the counterpoint of the piece emerging uncorrupted by technique or facility,

suddenly readable against struggle’s bright foil.

August 6, 2012

Contributor’s Marginalia: Sandy Longhorn on “Feeding the Geese” by Mary Angelino

With a quiet confidence Mary Angelino’s “Feeding the Geese” describes a familiar scene of human interaction with the natural world and then transcends that moment with a final stanza that makes me gasp with recognition, bringing to light a fear I had yet to articulate. Far too often poets writing about the natural world fall into the trap of the didactic mother-nature-teaching-us-a-lesson poem. Angelino deftly avoids this trap and makes new her subject, the speaker observing nature while keenly aware of the separate quality that makes humans stand apart from the natural world.

The poem opens with an erasure when the speaker states, “I am nothing to them,” and that, along with the title, sets up the age-old dichotomy of human versus nature, except this isn’t the speaker versus the geese. Instead, the poem explores the modern symbiosis of the two, the speaker bringing a bag of bread to the lake to feed the geese. We are in nature, but we are not in the wilderness. The speaker has come to commune and interact rather than to hunt and conquer, yet the speaker never completely steps into the natural elements. There is a separation that cannot be eliminated. Even the description of how the geese approach, all neck and peck, “as if their bodies were hidden under a table,” places us in a human environment. The idea of feeding the geese remains an artificial construct as the kitchen table hovers metaphorically over the landscape.

In stanzas two and three, the speaker fades from the scene even more as the supply of bread comes to an end and the geese return to the water. It is in these two stanzas that I hear the echoes of Yeats’ “The Wild Swans at Coole,” a poem not memorized but layered into my muscle memory by it having been taught to me by a Yeats enthusiast many years ago. While Yeats describes how the swans all take flight at once and “scatter wheeling in great broken rings,” Angelino describes the geese on the lake creating wakes that are “the spokes of a wheel.” When Yeats depicts the way the swans “drift on the still water,” Angelino’s geese sleep there “wooden tops / the wind has set to spinning.” In both poems one natural element layers on the next, building tension from line to line, even as the speaker remains a silent observer, knowing he/she will never truly be “of” nature, the separation created by the thinking mind too much a chasm to overcome.

It is in the fourth and final stanza of “Feeding the Geese” that the speaker returns full force, noting another human separator in the natural landscape, the bench upon which the speaker sits to observe, the bench that provides comfort and convenience and elevates the speaker, creating a distance from the nature observed. This distance is crucial to creating the force of the last line in the poem, when after having spent a brief interlude with the geese, the lake, and the wind, the speaker contemplates mortality. Rather than falling prey to the “nature lesson” of the cycle of life, the speaker resists, confessing to the wish for a long life but also to “still have [her] mind” when the end of that life nears.

It is in the fourth and final stanza of “Feeding the Geese” that the speaker returns full force, noting another human separator in the natural landscape, the bench upon which the speaker sits to observe, the bench that provides comfort and convenience and elevates the speaker, creating a distance from the nature observed. This distance is crucial to creating the force of the last line in the poem, when after having spent a brief interlude with the geese, the lake, and the wind, the speaker contemplates mortality. Rather than falling prey to the “nature lesson” of the cycle of life, the speaker resists, confessing to the wish for a long life but also to “still have [her] mind” when the end of that life nears.

Here is where the poem turns for me. I gravitate toward poetry that explores the human condition and offers me both empathy and wisdom. Angelino has certainly done both, leading by instinct and observation rather than by lecture to this pronouncement of something human and true. That last line lingers and haunts, as I am a woman approaching middle age, with aging parents, one of whom suffers from the loss of short-term memory, and two grandparents who slipped away into dementia before dying. Would I have recognized the brutal honesty and the threat of Angelino’s last line at an earlier age? I doubt it. Did I see this in Yeats’ poem all those years ago? No. But there too is the beauty of poetry. It will be there, always, waiting for the reader to catch up and take what it has to give.

—Sandy Longhorn

Sandy Longhorn is the author of Blood Almanac (Anhinga Press). New poems are forthcoming or have appeared recently in Cincinnati Review, Crazyhorse, North American Review, Waccamaw, and elsewhere. Longhorn teaches at Pulaski Technical College, runs the Big Rock Reading Series, is an Arkansas Arts Council fellow, and blogs at Myself the only Kangaroo among the Beauty.

Sandy Longhorn is the author of Blood Almanac (Anhinga Press). New poems are forthcoming or have appeared recently in Cincinnati Review, Crazyhorse, North American Review, Waccamaw, and elsewhere. Longhorn teaches at Pulaski Technical College, runs the Big Rock Reading Series, is an Arkansas Arts Council fellow, and blogs at Myself the only Kangaroo among the Beauty.

July 30, 2012

Contributor’s Marginalia: Catherine Tufariello on “To Light You to Bed” by Anna M. Evans

Unnecessary poetic epigraphs are a pet peeve of mine—particularly quotations from other poems. They tend to juxtapose the poem at hand with a better poem by a famous poet, with unfortunate results. They can suggest a lack of faith in readers’ ability to catch an allusion or influence. At worst, they are simultaneously pretentious and obsequious.

Anna Evans, though, knows how to make an epigraph work for her. Looking up the origins of the English nursery rhyme that Evans cites in the epigraph of “To Light You to Bed,” I learned that like other old children’s rhymes (e.g. “ring around a rosy”), it has a macabre history. Condemned prisoners at Newgate, awaiting execution by beheading, met their deaths as London’s church bells struck nine o’clock. When the bells finished ringing, the executions were completed until the next morning. Here is a common variant:

Oranges and lemons,

Say the bells of St. Clement’s.

You owe me five farthings,

Say the bells of St. Martin’s.

When will you pay me?

Say the bells of Old Bailey.

When I grow rich,

Say the bells of Shoreditch.

When will that be?

Say the bells of Stepney.

I do not know,

Says the great bell of Bow.

Here comes a candle to light you to bed,

And here comes a chopper to chop off your head!

Some versions end “Chip chop, chip chop, the last man’s dead.” The phrase Evans takes for her title is thought to refer to the warden’s candle, as he made his rounds the night before the condemned were to die.

“To Light You to Bed” opens with New Orleans crooning a contemporary Siren song to the tourist: not Tomorrow you will die but You can have anything at all you want. Like the nursery rhyme, like Mardi Gras, the poem mixes light tones and dark, pleasure and fear. I’ve never been to New Orleans, but Evans’ poem makes me feel surrounded by the sights, tastes, sounds and smells of Mardi Gras on Bourbon Street,

…. where drinks are three for one,

and breasts are two a penny after dusk;

where even matrons leave their shirts undone,

their bare breasts soaking in the city’s musk.

Formally accomplished and controlled, in cross-rhymed iambic pentameter quatrains, the poem plays with the desire to surrender control, to feel “a little roughly handled / by fresh desire.” In the first stanza the speaker catches a snake-like string of metallic red Mardi Gras beads, presumably thrown from a carnival float. As she walks the thronging streets–by turns vaguely uneasy, voyeuristic, nauseated, fascinated–she fingers the beads like a pagan rosary. An “angel” is led by her pimp; handmade signs threaten the crowd with eternal damnation; the smells of Cajun seafood, cigarettes, sex and nervous sweat fill the air. The poem’s neatly strung stanzas are like that Mardi Gras rosary for the reader, each representing not a prayer but a temptation, a come-on by the streets of the city. Replacing the London church bells, the streets of New Orleans speak, seductive and occasionally condemning: You have your needs (Bourbon Street), You’re all going to hell! (Toulouse Street), What d’y’all want for dinner? (Conti Street), Everyone turns tricks (St. Ann Street).

In the next to last stanza the warden’s candle, signifying the last night of the condemned, fuses with Millay’s candle burned at both ends: “I want to light my body like a candle,” says the narrator, “and burn out on an ancient pagan shrine.” In this fantasy of sexual desire as self-immolation, she imagines extinguishing the self that stands aside, self-consciously watching the parade. But by the end, the narrator is no longer sure what she wants, only that she hasn’t found it. Watching two strangers kiss (strangers to her and maybe also to one another), fiddling with her strand of beads as the cheap red glaze flakes off on her fingers, she is implicated with “the other sinners” in the carnival of excess all around her, even as she can’t quite lose herself in it.

—Catherine Tufariello

Catherine Tufariello’s poems have been featured on American Life in Poetry, Writer’s Almanac, and Poetry Daily. Her first book, (Texas Tech), won the 2006 Poet’s Prize. Her poem “Testament” appeared with Anna Evans’ “To Light You to Bed” in 32 Poems 10.1.

Catherine Tufariello’s poems have been featured on American Life in Poetry, Writer’s Almanac, and Poetry Daily. Her first book, (Texas Tech), won the 2006 Poet’s Prize. Her poem “Testament” appeared with Anna Evans’ “To Light You to Bed” in 32 Poems 10.1.

Contributor’s Marginalia: Catherine Tufariello on “To Light You to Bed” by Anna Evans

Unnecessary poetic epigraphs are a pet peeve of mine—particularly quotations from other poems. They tend to juxtapose the poem at hand with a better poem by a famous poet, with unfortunate results. They can suggest a lack of faith in readers’ ability to catch an allusion or influence. At worst, they are simultaneously pretentious and obsequious.

Anna Evans, though, knows how to make an epigraph work for her. Looking up the origins of the English nursery rhyme that Evans cites in the epigraph of “To Light You to Bed,” I learned that like other old children’s rhymes (e.g. “ring around a rosy”), it has a macabre history. Condemned prisoners at Newgate, awaiting execution by beheading, met their deaths as London’s church bells struck nine o’clock. When the bells finished ringing, the executions were completed until the next morning. Here is a common variant:

Oranges and lemons,

Say the bells of St. Clement’s.

You owe me five farthings,

Say the bells of St. Martin’s.

When will you pay me?

Say the bells of Old Bailey.

When I grow rich,

Say the bells of Shoreditch.

When will that be?

Say the bells of Stepney.

I do not know,

Says the great bell of Bow.

Here comes a candle to light you to bed,

And here comes a chopper to chop off your head!

Some versions end “Chip chop, chip chop, the last man’s dead.” The phrase Evans takes for her title is thought to refer to the warden’s candle, as he made his rounds the night before the condemned were to die.

“To Light You to Bed” opens with New Orleans crooning a contemporary Siren song to the tourist: not Tomorrow you will die but You can have anything at all you want. Like the nursery rhyme, like Mardi Gras, the poem mixes light tones and dark, pleasure and fear. I’ve never been to New Orleans, but Evans’ poem makes me feel surrounded by the sights, tastes, sounds and smells of Mardi Gras on Bourbon Street,

…. where drinks are three for one,

and breasts are two a penny after dusk;

where even matrons leave their shirts undone,

their bare breasts soaking in the city’s musk.

Formally accomplished and controlled, in cross-rhymed iambic pentameter quatrains, the poem plays with the desire to surrender control, to feel “a little roughly handled / by fresh desire.” In the first stanza the speaker catches a snake-like string of metallic red Mardi Gras beads, presumably thrown from a carnival float. As she walks the thronging streets–by turns vaguely uneasy, voyeuristic, nauseated, fascinated–she fingers the beads like a pagan rosary. An “angel” is led by her pimp; handmade signs threaten the crowd with eternal damnation; the smells of Cajun seafood, cigarettes, sex and nervous sweat fill the air. The poem’s neatly strung stanzas are like that Mardi Gras rosary for the reader, each representing not a prayer but a temptation, a come-on by the streets of the city. Replacing the London church bells, the streets of New Orleans speak, seductive and occasionally condemning: You have your needs (Bourbon Street), You’re all going to hell! (Toulouse Street), What d’y’all want for dinner? (Conti Street), Everyone turns tricks (St. Ann Street).

In the next to last stanza the warden’s candle, signifying the last night of the condemned, fuses with Millay’s candle burned at both ends: “I want to light my body like a candle,” says the narrator, “and burn out on an ancient pagan shrine.” In this fantasy of sexual desire as self-immolation, she imagines extinguishing the self that stands aside, self-consciously watching the parade. But by the end, the narrator is no longer sure what she wants, only that she hasn’t found it. Watching two strangers kiss (strangers to her and maybe also to one another), fiddling with her strand of beads as the cheap red glaze flakes off on her fingers, she is implicated with “the other sinners” in the carnival of excess all around her, even as she can’t quite lose herself in it.

—Catherine Tufariello

Catherine Tufariello’s poems have been featured on American Life in Poetry, Writer’s Almanac, and Poetry Daily. Her first book, (Texas Tech), won the 2006 Poet’s Prize. Her poem “Testament” appeared with Anna Evans’ “To Light You to Bed” in 32 Poems 10.1.

Catherine Tufariello’s poems have been featured on American Life in Poetry, Writer’s Almanac, and Poetry Daily. Her first book, (Texas Tech), won the 2006 Poet’s Prize. Her poem “Testament” appeared with Anna Evans’ “To Light You to Bed” in 32 Poems 10.1.

July 27, 2012

From the Archives: Two Poems on the Moon

If you haven’t read Lisa Russ Spaar’s recent article on moon-driven poems, I highly recommend it.You can find the piece here at the online home of the Chronicle of Higher Education. The comments she makes about her favorite lunar verse have had me thinking about some of my own nominations for best moon-inspired poems, particularly those from the pages of 32 Poems. Here’s a pair from our Spring 2008 issue (6.1): Ralph Black’s “One Bridge, One Whiskey, One Moon” and Kathi Morrison-Taylor’s “Apology for the Moon in a Poem.”

One Bridge, One Whiskey, One Moon

for J.L.

And two men leaning

on the riveted steel,

paying no attention

to the moon, the same one,

they know well enough,

that took poor Li Po

by the hand, and led him

that summer night deep

into his river’s delirious curl.

Two men, as the songs

will have it, tipping

plastic cups of whiskey,

talking, as poets do,

the diddle-dee-dee of poems:

the canal’s slurred cadence,

the darkened calligraphy

of the town. No one hears

what their words ignite.

No one sees the tiny bells

of smoke purling away

from their mouths.

And as they talk, the moon drops

over and over into the current,

shattering, as moons do,

a thousand years of poems.

Ralph Black’s poems can be found in Massachusetts Review, Lyric, and West Branch. He lives in Rochester, NY, and teaches at SUNY Brockport.

↔

Apology for the Moon in a Poem

Embarrassed, the poet notes the moon

made four appearances in her poem, sorry.

So sorry is she for putting in four moons,

she says it again, sorry.

And with her sorries the moon swells

fuller than four, a full that makes an audience

blush and wish they hadn’t noticed.

Since she had that dream of walking

through the mall naked, she hasn’t felt

as awkward as this apology morphing

into pregnant pause, phasing,

not fading, as a pale orb rises at reading’s end,

touching her audience, stomachs waxing,

round with moon cake and words.

As the rabbit in her moon thrashes,

she’s left cringing. Let a cloud pass over her face.

She will save her howling for later.

Kathi Morrison-Taylor’s first book, A Child of the Original Tree, was published by Word Works in 2008. Her work has appeared in New York Quarterly, Seattle Review, and Beltway Poetry Quarterly.

July 23, 2012

Contributor’s Marginalia: Bruce Bond on “Strict Traffic” by Jessica Piazza

In his essay “Poetry and Abstract Thought,” Paul Valéry claims that prose is to poetry as walking is to dancing. Prose thus calls upon a language that is more transparent, more intent on getting from place to place, more utilitarian than poetry that would relish the expressivity of bodies as they move. His analogy makes of the practice of the prose poem an odd spectacle indeed, walking and dancing at the same time, casting off the hesitations of the line break for something less removed, more dressed down, and yet, as a poem, called upon to open and intensify in spite and in light of the missing architecture. The very word “prose poem” conditions our expectation, wherein we might slow down and look to the language to give us more, to radiate a bit of a poem’s complexity and fire.

Dan Fogel, Open

The strange lyricism in the poem “Strict Traffic” by Jessica Piazza offers precisely that kind of generosity. With the authenticating informality of prose, it deploys all the swift movement, conceptual resonance, emotive intensity, and musicality of the lyric and so negotiates a territory between poetry and prose, between the luster of the one and the bedrock of the other. “I hunt. I haunt,” the speaker says, and the prevailing spirit of incantation summons a vision of the dead body as partly hers, partly that of “her bloodline,” that foundation below that bears the traffic of the living.

The music here is key to the spell of the poem, but so too is the suppleness of associative logic and argument that moves from subjunctive to declarative, deeper into faith where the speaker sorts through the bewilderment of grief with a wit that, through its speed and careful tonal pitch, gives grief its thoughtful vocation: “only rubble settles; people don’t.” So the dead are alive and yet not; they are the stuff of earth and yet not; they bear the weight of us and our traffic, and yet they walk with us, in us, in the mourner we meet, in the walking coffin of her body. One dead man in particular, revealed finally as the speaker’s father, as more openly personal and yet transubstantiated into archetype, haunts her, as she too haunts him, such that contradiction becomes a form of precision in the poem, of voicing the reciprocity in her felt relation to the dead.

In all its meaningful oddity, the poem exemplifies a broad sensibility—both soulful and meditative, heartsick and resilient, austerely physical and imaginatively rich. Thus, as the poem develops, we might feel increasingly the tension of opposites as they proliferate. We might sense a strictness to the traffic here, a dynamic force beyond control and yet disciplined, as all good poems are, by the pressure of emotional necessity to find its own “transubstantiation,” its own redeeming grace in the raw materials of “wet and salt” and the words they leave behind.

—Bruce Bond

Bruce Bond’s recent and forthcoming collections include Choir of the Wells (Etruscan Press, forthcoming), The Visible (LSU, 2012), Peal (Etruscan, 2009), and Blind Rain (Finalist, The Poet’s Prize, LSU, 2008). His poems “Crown” and “Winter” appeared with Jessica Piazza’s “Strict Traffic” in 32 Poems 10.1.

Bruce Bond’s recent and forthcoming collections include Choir of the Wells (Etruscan Press, forthcoming), The Visible (LSU, 2012), Peal (Etruscan, 2009), and Blind Rain (Finalist, The Poet’s Prize, LSU, 2008). His poems “Crown” and “Winter” appeared with Jessica Piazza’s “Strict Traffic” in 32 Poems 10.1.

July 21, 2012

When a Poet is Read and Read About

It was announced last month that Natasha Tretheway will be the next Poet Laureate of the United States and in doing so will be the first Southern Poet Laureate since Robert Penn Warren, the first person to hold the position. She will also be the first African-American Poet Laureate since Rita Dove, who served from 1993 to 1995. Already the Poet Laureate of Mississippi and a professor at Emory University, Natasha Tretheway has been a star in the world of poetry and beyond for years, winning the Pulitzer Prize for Native Guard in 2007 and writing several respected books of poems and a book of nonfiction, Beyond Katrina: A Meditation on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Her fourth collection of poetry, Thrall, is forthcoming this fall, and perhaps most startlingly, her decision to write a memoir resulted in an auction among publishers for the right to print it. Ecco came out the winner, and on July 1st The New York Times quoted Daniel Halpern, Ecco’s president and publisher, as saying, “I can’t remember a more emotionally intense auction for a book, ever.”

It’s possible to see Tretheway’s career as one paved in gold—the daughter of a poet (her father is a professor of English at Hollins University), she has hit nearly every major mark of success available to a poet in the United States and achieved a level of acclaim and visibility that transcends the normally insular world of verse, all by the astonishing age of 46. But as readers of her work may know, her life has been difficult, scarred by the murder of her mother by her second husband when Tretheway was only 19. This is a fact that stuns, but it also partly explains the intense interest in her memoir. The fight among publishers over the privilege of printing the book can be seen as a triumph for poetry: a moment when a poet emerges with something not only relevant and compelling to say, but with the appeal and visibility to say it widely. On the other hand, this attention comes for a book of prose, not poems, and reminds us of the indifference of commercial enterprise toward poetry.

It’s somewhat disturbing that while most articles describing Tretheway cite her CV (her “poetry credentials”), they avoid conversation with the poems themselves. Much space and energy is given to her race, gender, and geographical provenance, but a critical response to the work is lacking. There are, after all, many poets who, like Tretheway (Southern, African American, female), buck historical trends and write work that is worthy of serious recognition. I think we can reasonably ask why so much attention should fall to one poet and question whether the attention of the media and commercial publishing is attention that helps poetry or potentially distracts from poems. If the gaze of major publishing houses and the mass media results in a narrowing or pigeon-holing of the discourse about poetry, or focuses entirely on the person of the poet, then perhaps we should look at these types of stories skeptically. It seems inarguable to me that as readers of poetry we should raise our voices in praise of the gifted poets this country is teeming with, and that our praise should be tied to the pleasures of their poems.

What do you think? Can great recognition for a poet distract from the poems themselves? What poets’ work would you like to see share the limelight in a serious discussion of contemporary poetry?

—Jasmine V. Bailey

July 16, 2012

Contributor’s Marginalia: Dan O’Brien Responds to Philip White’s “Childlessness”

Childishness

Is it pure choice or pure chance that I write

this poem about another poet’s poem

on Father’s Day? A day of surfacing

disequilibrium. Rage, then shame with those

who don’t have a father. Or a father

we never really could stand. Just a man

small with envy and cruelty. “Childlessness”

is a poem so wise with relief and dread

I feel as if I could’ve written it

myself. Had I this man’s gifts. The last thing

my father ever said to me was, When

did you break faith with your dream to become

someone? But I digress. “Hell behind me

and Purgatory open/ in my hand,”

quoth the poet. He’s revisiting Dante’s

Commedia, of course. One will remember

the dog-eared collegiate copy. Laboring

to burn off one’s childhood in the middle

of a tapering life, in the middle

of this forest blind and stern. Not unlike

our poem’s villa. Cataracted “jackdaws

clacking” in the clanging blooms. A lot like

the promontory and the ivory-breasted

waiters of Bellagio. The fogged flurries

in Sewanee, TN. The numinous

threat of Shanghai next week. The Pacific

caerulean shelf a dogwalk away. Luck

sometimes leads me to a good, long nap. But

always “someone else is here, dividing,/

provoking.” What? Guilt? Solitude? This lack

of family, a child of one’s own. This curse

of a “father/ at the door looking in”

on the poet at work. And should the son

meet the father’s spectral gaze, the father

will sit down and stay a while. And who knows

what crime we have in common? The tenor

of Dante invites vivid, disfigured

recollections. Of “pure choice” the poet

recommits to the page. Each time I read

this poem the title “Childlessness” becomes

“Childishness.” As if the father’s lingering

presence keeps me what I am. Italian

children pillaging the park certainly

support my thesis. Or maybe I’m wrong

and the childless one’s of course the father

whose son won’t ever look up, whose son wants

nothing more than to be free of this God

damned ghost.

↔

photo by David Bornfriend

Dan O’Brien was recently a fellow at the Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Center in Italy. His play, The Body of an American, will premier at Portland Center Stage this fall. His poem, “The Dead End,” appeared with Philip White’s “Childlessness” in 32 Poems 10.1.

July 13, 2012

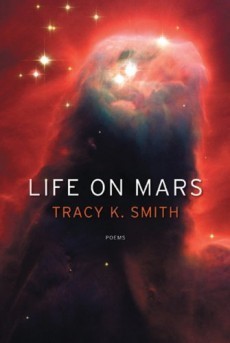

A Belated Note on the Pulitzer Prize

Although it’s impossible to know what goes into the Pulitzer poetry committee’s decision each year (having read every nominated book, would you have chosen the same? what arguments did the readers make on each volume’s behalf?), their choice is an occasion for readers of poetry to encounter a contemporary book of poems that has already been given a special stamp of approval, something like canonization-in-advance. It’s easy enough to dismiss a contemporary book based on the obscurity of the writer, press, title, or series. Indeed, it can be difficult to choose a one to read, given that so many are published each year, and so few stand out as ones that we ought to prioritize on our reading lists. The Pulitzer Prize and other major awards are a simple way for many readers to manage the chaos. As a result, those books chosen enter the national discourse in a way others (especially poetry) do not, so reading them involves us in a larger dialogue with other readers. It should be noted that winning a major award also opens a poet up to criticism the likes of which they would not otherwise encounter. Every reader of Tracy K. Smith’s Life on Mars is, to some degree, sizing her up, passing judgment, taking an explicit or silent stance as to her worthiness of the immense recognition the Pulitzer grants. With all that in mind I wanted to read her book innocently, as a book rather than as a Pulitzer-Prize-Winning-Book, and to share some impressions with our readers.

Perhaps I was disheartened initially to read a little about Tracy K. Smith and realize how successful a poet can be and still be widely unknown, even to avid poetry readers. Life on Mars is her third book; her first, The Body’s Question, won the Cave Canem Poetry Prize, and her second, Duende, won the James Laughlin Award. By my reckoning, these are serious laurels, besides which, she teaches at Princeton. And yet, the phrase I heard from many educated lips when the 2012 Pulitzer was announced was, “I’ve never heard of her.” At the end of her book I arrived at the acknowledgements page and learned one reason for Smith’s obscurity: while some of the poems from Life on Mars appeared in print magazines (including Bat City Review, Cimarron Review, Tin House, Ploughshares, and The New Yorker), almost as many appeared in video format on a far less-visible website (rolexmentorprotege.com), as audio on a BBC radio show, and on brooklynpoetry.com. Although as a poet I am amazed that so many poems from the book were published in unconventional ways, I can’t help but think this choice shows a special commitment on Smith’s part to alternative media as a forum for poetry. It is also, of course, an aesthetic statement.

Perhaps I was disheartened initially to read a little about Tracy K. Smith and realize how successful a poet can be and still be widely unknown, even to avid poetry readers. Life on Mars is her third book; her first, The Body’s Question, won the Cave Canem Poetry Prize, and her second, Duende, won the James Laughlin Award. By my reckoning, these are serious laurels, besides which, she teaches at Princeton. And yet, the phrase I heard from many educated lips when the 2012 Pulitzer was announced was, “I’ve never heard of her.” At the end of her book I arrived at the acknowledgements page and learned one reason for Smith’s obscurity: while some of the poems from Life on Mars appeared in print magazines (including Bat City Review, Cimarron Review, Tin House, Ploughshares, and The New Yorker), almost as many appeared in video format on a far less-visible website (rolexmentorprotege.com), as audio on a BBC radio show, and on brooklynpoetry.com. Although as a poet I am amazed that so many poems from the book were published in unconventional ways, I can’t help but think this choice shows a special commitment on Smith’s part to alternative media as a forum for poetry. It is also, of course, an aesthetic statement.

The poems in Life on Mars, too, are an interesting mixture of the tropes we often see as dichotomies: high and popular art, science and spirituality, the timely and the eternal. I admired the book most for its political critiques of contemporary American society. These are not always the most elegant poems, but they are sometimes boldly experimental. The two poems that interested me the most, the title piece and “They May Love All That He Has Chosen and Hate All That He Has Rejected,” are both political poems in multiple sections that move between a narrating speaker, figures from current events, and pundits commenting on the events those figures are involved in. “Life on Mars” begins, “Tina says what if dark matter is like the space between people / When what holds them together isn’t exactly love.” Here, we have Smith in two modes she works in throughout the book successfully: the intimate speaker interacting with her loved ones and the inquisitive mind asking philosophical and spiritual questions of science. Most of the poems engage science, especially astronomy, in some way, and we have, by the time we read this poem, learned that the poet’s father worked on the Hubble Telescope. From the opening lyrics on, the speaker approaches science not just as a matter of intellectual curiosity, but also as a topic with the gravity of family, and love, at its core. After a beautiful elegy to her father, Smith’s questions about dark matter seem fraught with the love of a child toward a parent and the struggle to make sense of loss.

“Life on Mars” moves from an intimate scene, a conversation with epistemological questions, to a section that takes place in the home of a man who’s kept his daughter locked in a cellar for years as a prisoner and sex slave. Next, the poem switches back to Tina’s contemplation of dark matter, then transitions to a dramatic monologue in the voice of a woman about to be gang-raped, before returning again to the philosophical speaker. Later we encounter a section about the soldiers in Abu Ghraib Prison humiliating the inmates, a section interspersed with comments we can discover belong to Rush Limbaugh, and in the penultimate section we find a lyric governed by the anaphora “the earth.” This section is almost without syntax and seems generated by the eye of a bewildered person seeing, “The earth beneath us. The earth / Around and above…The earth caked to mud in the belly / Of a village with no food.” The final section returns to Tina and the ongoing meditation on the space between people, “When it is love, / What happens feels like dumb luck. When it’s not / We’re riddled with bullets,” and ends with the questions, “And what / If what it is, and what sends it, has nothing to do / With what we can’t see? Nothing whatsoever / To do with a power other than muscle, will, sheer fright?” While this poem’s sections are only nominally connected, and while the strain of the philosophical meditation with Tina could be more powerfully and compellingly realized, the ambition of this poem is striking, and the final gesture of those questions (in light of all that the poet has attempted to weave together and see as part of a whole) touches me as the sincere queries of a person who wants to believe in a compassionate God and who struggles with the evidence of reality.

I also admired this poem as one unafraid of its own deadly gravitas. The second most-common motif in the book is David Bowie, who is at times named directly or referenced in italics. Even “Life on Mars” takes its title from one of his songs. I prefer the oblique reference to what I find Bowie’s burdensome and distracting presence in poems such as “Don’t You Wonder, Sometimes?” in which the poet seems to back off her own serious material to reminding us the poem is also about David Bowie, and therefore not too depressing. In “Life on Mars,” Smith is courageous about what troubles her and Bowie is subservient to that, rather than somehow giving her permission to discuss weighty philosophical and political topics because his unexpected presence in the poem blunts the edge of her critique.

In another startling poem, “They May Love All That He Has Chosen and Hate All That He Has Rejected,” Tracy K. Smith engages five murders reported by the New York Times in May and June of 2009. They are not very well-known cases, and they are not united by any single irony: in one, an on-duty police officer kills a black off-duty police officer who is going after a man breaking into his car, in another an abortion doctor is killed by an abortion protestor, in another a Wesleyan student kills a classmate after writing anti-Semitic rants in his journal, militiamen (and a woman) kill a family at random in their home, and an eighty-eight-year-old man opens fire in the Holocaust Museum, killing a security guard and then being killed himself. The disparate nature of these killings, detailed in the notes, is not dwelt upon in the poem, which treats them all as what their grouping suggests: examples of the senselessness and profane exploitation inherent to violence and murder. The poem’s first section establishes the speaker’s preoccupation with the news stories, which is their foremost unifying force: “I don’t want to hear their voices. / To stand sucking my teeth while they/ Rant.” In its early sections, the poem moves through meditations on hate and the journey of death, and in part three names the characters. Part four, “In Which the Dead Send Postcards to Their Assailants from America’s Most Celebrated Landmarks,” produces just that: notes penned, victim to assailant, from all over the US, in tones ranging from sweet (as with the eight-year old girl) to restrained to near-indifferent (as the cop who says “I don’t think of you often,” which of course affirms that he does think of him). The poem returns in its final two sections to a contemplation of the assailants, who are the fascination and problem of the poem, trying to make sense of their motives and their souls given that the speaker’s own motives and soul fail to explain them. The act of imagination stands as the only recourse for a connection between the self and the murderers she’s read about.

Though it is much more formally experimental than “Life on Mars,” “They May Love All That He Has Chosen and Hate All That He Has Rejected,” is similarly unafraid of its seriousness and less-refined than the many of the poems in the book. Still, these pieces are probably the most compelling reason to read Life on Mars: they are risky tonally, formally, and in terms of content, and they wear that risk, the roughness around the edges, candidly. There are also poems in Life on Mars that are elegant and heart-rending, (the elegy for Smith’s father, “The Speed of Belief” is actually my favorite) and a few that are neither bold and risky nor very beautiful. Without speculating upon the reasons of the Pulitzer committee, I say this book, like its predecessor, Duende (which is interesting for its own reasons), is worth reading as an example of a vital, feeling American voice in a poet of worldly, intelligent scope.

—Jasmine V. Bailey

July 11, 2012

New Web-Tool for Writers: LitBridge

Whether you’re researching graduate programs in creative writing, book contests, or just submitting to literary magazines this summer, we recommend a visit to the LitBridge website. In addition to gathering links and screening an enormous amount of information on the creative writing community, the folks at LitBridge have also prepared a number of articles on topics like coordinating a reading series or applying to MFA programs. It’s another site like Duotrope or Poets&Writers that can save poets a great deal of time and energy. And wouldn’t we all rather spend that time with the page?