Deborah Ager's Blog, page 2

July 1, 2013

Our God is a Consuming Fire: Fourteen Reflections on Joanna Pearson’s “The Arsonists in Love”

Contributor’s Marginalia: Benjamin Myers on “The Arsonists in Love” by Joanna Pearson

1.

If Joanna Pearson’s poem had a theme song, it would be Joy Division’s “Love Will Tear Us Apart,” which I listened to for almost twenty hours straight, locked in my bedroom at sixteen, staring at the flimsy brown wood paneling between the posters on my wall, after my first girlfriend dumped me, but which I also still think is a superb song.

2.

This poem takes off with a conflagration of sound: “We lusted after luster, lit our fill.” The alliteration calls to mind the first lick of flame as a fire begins. The movement from low vowels to high is a kind of igniting whoosh that gives the poem energetic propulsion. The vowels and consonants continue to crackle and pop with heat throughout the rest of the poem, creating a sustained onomatopoeia, a technique sometimes utilized in poems about jazz or about modern machinery, but used with startling originality to conjure up a fire in Pearson’s poem. This is a poem for reading aloud, for recitation late, late in the night when you sit in the circle of the last people to leave the party.

3.

In high school, I had a friend whose favorite party trick was to spray his jeans with hairspray and light them on fire. He particularly liked to light his crotch. I can still smell the sweet hairspray turning to acrid flame, see the stone-washed marbling take flame and oddly illuminate his torso and face. We all knew it must be a metaphor for something. I don’t know where that friend is now.

4.

Fourteen lines of ten syllables each gives the sonnet such a boxy look, which is absolutely perfect for this house on fire. Pearson’s assonances are like tongues of flame arching out from windows and cracks in the siding. I love to watch this poem burn.

5.

The English sonnet is often referred to as the “Shakespearean sonnet,” but the form was actually first used by Henry Howard, the Earl of Surrey. Still, we call it the “Shakespearean sonnet.” Surrey got screwed.

6.

I love a good line break. I have heard that term challenged, the idea being that, in carefully constructed poetry, we don’t “break” a line but rather end it fittingly, either with or against the syntax. But witness this: “as if we could make love / destroy itself.” That line is beautifully broken.

7.

There is, perhaps, a bit of Gerard Manly Hopkins behind this poem. I think, naturally, of “That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire and of the Comfort of the Resurrection.”

8.

I’m drawn to the image of the lintels cracking like wishbones. There is something very compelling about the tension between the warm, homey connotations of Thanksgiving dinner and the destructiveness of the criminal act at the heart of the poem. Unless, of course, your family Thanksgivings already bordered on, or descended into, criminal acts. Then I suppose rather than interestingly tense, the image is more simply apropos. Either way it is a heck of an image.

9.

While I’m on the topic of imagery, I’d like to say something about the ending of the poem. It’s splendid the way Pearson draws the reader into the imaginative action of the poem, asking the reader to help imagine a form for the “blotting shape” that looms above her characters. The image is somehow both vivid and ambiguous, and that ambiguity gives the poem a sort of open-endedness that is perhaps rare in sonnets. You might even say that Pearson solves a significant problem in postmodern formalist poetics here, managing to give the sonnet form its particular kind of closure and yet maintain postmodern resistance to closure. That all sounds rather academic, but the upshot is that the end of the poem is all the more moving for the way it tugs us, like a difficult relationship, back and forth between a sense of ending and a sense of going on.

10.

This according to Thomas Merton’s The Wisdom of the Desert: “Abbot Lot came to Abbot Joseph and said: Father, according as I am able, I keep my little rule, and my little fast, my prayer, meditation and contemplative silence; and according as I am able I strive to cleanse my heart of thoughts: now what more should I do? The elder rose up in reply and stretched out his hands to heaven, and his fingers became like ten lamps of fire. He said: Why not be totally changed into fire?”

11.

Sometimes it scares me how much I love my wife. I would burn a house down if she needed me to.

12.

Even if it is a less arduous task to rhyme the Shakespearean (or, shall I say, Surrean) sonnet than it is to rhyme its more ornate and Italianate cousin, the Petrarchan sonnet, it is still no small feat. Pearson achieves the rhyme scheme of the sonnet with grace, particularly with rhymes like “joist” with “rejoiced” and “cracked” with “act.” Such rhymes keep the form tight aurally but surprise the eye, another form of tension in this carefully fraught poem.

13.

“It was a flagrant act / to burn the place we lived. . . .” Brilliant diction! (flagrant from the Latin, flagare, “to burn”).

14.

“Love, love will tear us apart . . . again. . . .”

—Benjamin Myers

Benjamin Myers’ latest book is Lapse Americana (NYQ Books, 2013), and he won the 2011 Oklahoma Book Award for Poetry for his first book, Elegy for Trains (Village Books Press, 2010). Besides 32 Poems, his work may be read in Poetry Northwest, Measure, The New York Quarterly, Devil’s Lake, and many other journals. His poem, “Spook House,” was recently featured on Verse Daily, and several of his poems have been featured in the Everyday Poems newsletter. He frequently reviews books of contemporary poetry and books on poetics for World Literature Today. A native of central Oklahoma, he was educated at the University of the Ozarks and at Washington University in St. Louis. He is currently the Crouch-Mathis Associate Professor of Literature at Oklahoma Baptist University.

June 28, 2013

Weekly Prose Feature: “A Collaborative Interview on Collaborations, Part 2”

On April 19, we featured the first installment of this ongoing interview series; for part two, we’ve asked a variety of types of collaborators to chime in on our questions:

Poets Maureen Alsop and Joshua Gottlieb-Miller have an ongoing call-and-response poem collaboration.

Visual artist Kathy Barry and poet Jocelyn Casey-Whiteman met while both in residency at the Vermont Studio Center and collaborated both in person and long distance from their respective homes in Auckland, New Zealand and New York City; a selection of their work can be found in Threaded .

Poets (not to mention mother and son) Marie Harris and Sebastian Matthews began their project, Bruised Heart, after Sebastian and his family were in a car accident in August 2011.

Poets Ryan Teitman and Marcus Wicker have co-written a number of poems; read a selection in Pinwheel.

QUESTION 1: How does one start a collaborative project?

Maureen Alsop: At the beginning.

Joshua Gottlieb-Miller: That’s a trick question, right? But of course, one must start a collaborative project, even if it takes two to etc. etc. I’ve always found there’s nothing better than persistence, guidelines, and trust in your partner’s differences. Unless you’re willing to not get in the way of the other person’s interests and style, the collaboration will never really start.

Kathy Barry: I had been invited to contribute a practitioner’s profile to an Auckland-based publication with the option for collaboration. I asked Jocelyn to collaborate with me as I had admired her poetry on residency and thought that our work shared certain qualities. Fortunately we were able to meet in New York to start the collaboration before I returned to New Zealand so the whole project didn’t happen via computer.

Jocelyn Casey-Whiteman: I think it starts with some spark of curiosity about the other artist’s work. Kathy and I met at the Vermont Studio Center in the summer of 2012. I was interested in her drawings and creative process, which includes meditation, so when she approached me about a collaborative project, I agreed.

Marie Harris: In the months that followed the accident, Sebastian crafted a series of poems and collages chronicling the experience from his vantage; and I made my poems. For a while it seemed these were two separate endeavors. But as time passed and as I read his work, I began to realize that the accident had caused long-suppressed issues to boil up; I needed to initiate a ‘conversation,’ both with him and with myself. Sebastian had chosen a format for his explicitly “accident” poems (which included accompanying photo-montages) and a slightly different format for his “Dear Virgo” poems which served as a sort of commentary on the other series. I found this an intriguing approach and began to realize that I could write my ICU poems in one voice, and make the “Dear Scorpio” poems in another (in my case, a younger self speaking to the older self), thereby giving me the framework in which to describe the immediate trauma and also address the aforementioned “issues.” And, because I haven’t a visual art bone in my body, I gladly relinquished the collage work to Sebastian, doing nothing more than supplying him with images (culled from the photos his stepfather took at the hospital and from photos and documents from his baby book) that he was free to use or not as he chose.

The resulting poems are not meant to be read one-to-one, but encountered as one might eavesdrop on a conversation overheard between two people in whom the reader might recognize kindred spirits, shared experiences. And I see them as two halves of a whole book.

Sebastian Matthews: I wrote these two sets of poems each as part of the on-line collaborative project The Grind. My mom also wrote many of her poems during these one-month “grinds.” This kind of daily writing allowed for the work to come out relatively free of self-consciousness. I just wrote the poems, and made the photomontages, as part of a morning practice. I let them pile up in a file.

The hard part, and the creatively engaging part, has been placing my poems alongside—in conversation with—my mother’s work. And then working on photomontages for her poems. My mom and I have always offered feedback on each other’s work; we’ve been doing it since I was a teen and she let me join her at Jean Pedrick’s Skimmilk Farm workshops. But this has deepened our creative connection, I think. We’ve both been forced to push ourselves outside our comfort zones.

Ryan Teitman: Distance was one of the things that spurred us. I was in Berkeley, Marcus was in Provincetown. Writing poems together through email was a way to keep in touch, both as friends and as poets.

Marcus Wicker: Really the project began as a way to keep in touch and continue learning from one another beyond graduate school. After three close and productive years together at Indiana University Ryan took a Stegner Fellowship at Stanford and I found myself on the other side of the country at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown. I won’t speak for Ryan, but I was between projects—revising my first collection and trying to write new things, which mostly felt like B-sides of the work in Maybe the Saddest Thing. I needed to get out of my own way, delve in new modes, and our collaborative efforts allowed me to do so in a pressure-free way. We started a few lines at a time via email and liberally. Sometimes I’d write a couplet and Ryan would send back three or I’d pen four lines and he’d shoot back one. I get a sense that our drafting process changed with our day-to-day workload.

QUESTION 2: How does one know it’s done? Do you set parameters at the beginning or does it fizzle out?

MA: We know it’s done because we like it. Yes, we set a framework initially and follow the Minotaur through the maze.

JGM: I rarely set parameters for ending collaborations. I see collaboration as inherently generative: you trust that your partner will make better what you make, so you are free to create. Parameters for the beginnings of poems help create common ground, since style/voice/whatever really does distinguish down to each word who’s contributing what. Bad poems fizzle out. Good poems end. (Though one is not always the good poet who saw it was done first.)

KB: Meeting our initial deadline left us with a sense of untapped possibilities, of not having finished what we might do together.

JCW: Kathy and I are still in the midst of collaboration, and, so far, we haven’t set parameters other than meeting a deadline.

MH: There’s a difference between a poem or poems that are actually written collab-oratively (as in a renga or on the Exquisite Corpse model) and a collaborative project. Bruised Hearts is an example of the latter. We knew when this project was done because we established numbers for the poems in each of our sections. Sebastian and I have commented on and critiqued each other’s work for years.

RT: We had the good fortune of our collaborative work being slowed by good news. My first book was picked up by BOA Editions and Marcus won the National Poetry Series. We had first book concerns to tend to, so the collaboration got pushed to the back burner.

MW: A good deal of our poems were born from one-upmanship. I’m thinking of one poem in particular, “A Game of Chicken,” where Ryan changed the tone of a perfectly chiseled, solemn opening (in my head, at least) with three questions. To “get him back” I sent back four questions and he replied with another before shifting gears as if to say “uncle.” I suppose we let the process dictate how and where to end a poem.

QUESTION 3: Talk a little bit about the etiquette of authorship. If you’re both writing poems, do you seek publication together or separately?

MA: Together, with our collaborative poems. We share the submission process.

JGM: I’m worried more about the etiquette of collaboration. In this project we work on the same poems together. It’s important that we respect each other enough to push the work as hard as it will go, and to pull back when the other person has a clear priority in the poem (almost like running track or swimming laps, or being on a basketball team with someone who can’t miss. Feed them the ball!)

The poems sort themselves out the same way, in terms of publishing: I tend to send out the ones I like more, and Maureen tends to send out the ones she likes more, we each stay in the loop about what’s been submitted where.

I think it’s trickier with poems written in response. How could you not send those out as your own individual poems, but wouldn’t you want to reference somehow their creation as part of a larger project?

RT: We’re both listed as authors on our journal publications. Marcus has been the mastermind of the submission process.

MW: Always together. We shoot for one singular voice in each piece. From draft to final product, who wrote what is sometimes unrecognizable.

QUESTION 4: How does collaboration help you in your own work?

MA: It pushes me between down times (& up times).

JGM: I’d kind of scared myself away from the lyric in graduate school. Seeing other approaches to poetry work so beautifully is easy enough as a reader, but actually participating in other approaches allows me to experiment far more freely. Paradoxically, it also makes me much more conscious of my more conservative impulses (towards some story structure), and when those impulses are appropriate/constructive (constructive in the generative sense).

KB: Jocelyn’s ekphrastic poems unlock interesting new ways to think about and experience my drawings. They bring about a merging of our individual sensibilities, which I imagine will be generative for future work.

JCW: The invitation to live in the world of Kathy’s drawings allows my mind to travel to unfamiliar landscapes that stir my sensibility and thoughts in a manner that is new and welcome to me. Kathy introduced the collaboration during a time when I struggled with health issues and was exhausted. As I sit with her work, the process of writing is both creative and healing. Her sensitivity to line, light, shadow, and pattern creates a spacious feeling which allows me to reach past the limits of my conscious experience.

RT: It really shows where your strengths and weaknesses are. I recently got stuck on a poem and thought: “How would Marcus handle this poem?” And I was able to take the poem in a new direction. That was much easier to do because we had worked together collaboratively. It’s like having another poet’s set of tools to borrow.

MW: When I’m at my desk alone and venturing into unfamiliar territory—I’m talking tone and form—there’s always a chance I’ll stuff a draft in a drawer too soon, because initially, the process can feel painfully uncomfortable. When working with a poet as good as Ryan you learn new and interesting ways to see a poem through to that final punctuation mark. After the third or fourth piece we co-wrote, I was willing to try anything in my own work.

QUESTION 5: Why do a collaboration?

MA: It’s surprising, a process of growth and trust.

JGM: I like to help make art that surprises me.

JCW: I think there are many reasons to collaborate. When you feel caught in a particular pattern of thought or feeling, introducing a new artistic energy may steer your imagination towards an unexpected place that brightens your art and yourself. Collaboration holds the potential to expand your perspective and your work.

KB: There’s a social aspect of collaboration that’s appealing also. Both artists and writers generally work alone, unlike the other creative industries: music, theatre, dance… So, to share one’s process, or to engage discrete practices in a conversation, is a welcome opportunity. Likewise, the various industries can be insular, so to work with someone from another field seems expansive, and a way to build communities. Also, because VSC hosts both artists and poets, our collaboration seems like an appropriate outcome to that particular residency experience.

MH: As a poet I have collaborated with a number of artists, most of them painters, sculptors and musicians. That sort of cross-pollination has had its own interesting rewards and surprising results. I’ve never been part of a translation project, itself a very particular form of collaboration, nor have I suggested any sort of collaboration to another poet until now.

So the current project—BRUISED HEARTS—which I’ve embarked upon with my son, the poet Sebastian Matthews, is an entirely new adventure for me. It had its genesis in a shared crisis: Sebastian and his family were nearly killed in a head-on collision. His wife and son were taken by ambulance to a nearby hospital, while he was helicoptered to a trauma center two hours away. And it was there that I spent the next 10 days (while his wife’s family tended to her) coping with the fear, distress, pain, bureaucracy, incompetence and grace that make up the experience of an emergency and its aftermath.

SM: That this collaboration comes out of such a calamity, such trauma . . . well, it’s hard to believe I was able to write about the event at all, or that Marie could find a way to write from her vantage. I’m glad we did, though—glad that we pushed through and worked on this project together. The whole process has been cathartic, healing. It’s been almost two years since the accident, and it feels as though making this work together has helped me move out of that stuck place. I have grown into a new post-accident life in part because of this collaboration.

RT: It lets you write with a new voice, one that isn’t entirely your own. And writing with a talented friend is a reward too.

MW: To prove that poets don’t have trust issues. I’m kidding. Because it’s fun and challenging, both.

QUESTION 6: What is your definition of collaboration?

MA: Co = collective, company; Lab= eLABorative, as in a lab to experiment; Tion= action

JGM: Anything where an artist’s contribution surprises the other artist who’s working on the same thing.

KB: Collaboration holds the potential to work beyond one’s existing boundaries, to work across disciplines and to cross-pollinate ideas, it necessitates letting go and being open.

JCW: A collaboration is a mutual agreement to share work, energy, experience, and ideas to create something new.

SM: For me, collaboration keeps the creative process—the writing life—dynamic and fluid. It gets me out of my own little world (headspace, attitude, bias) and challenges me to fuse my ideas and images with others. It also deepens friendships (if all goes well!) and radicalizes the writing act by creating a co-authorship. All good things in my book.

RT: Driving a car with two steering wheels.

MW: I don’t have a concrete definition but for me its equal parts trust and troubleshooting.

QUESTION 7: As a poet or artist, how and when do you collaborate with other poets?

MA: When ever the opportunity arises, it’s a 3-D conversation, a meeting of time and space. Josh and I met at the Reno airport.

JGM: Whenever they want to and I respect their work. It helps if they’re interested in something completely different, some other music or style, so that it’s collaboration and not just mimicry of the same noise.

RT: When you have something to say that can’t be said by your voice alone.

MW: Joint readings are a good opportunity to soak-in and compliment other poets’ work. Sometimes that means harnessing levity following a smart but guarded set. Or tapping into a fellow readers’ triumphs and offering up a poem or presence that shares a kindred experience. As far as writing goes, I’d like to think I’m a pretty monogamous collaborator.

QUESTION 8: What was your best collab? What made it successful?

MA: Our body of work to date, the fact we keep going. It makes one feel like the journey of writing is worthwhile.

JGM: There’s a poem we worked on that has some references to Israel. For me this is a Jewish poem. Maureen put a Mary right in the title, though. I’m still not sure either of us knows fully what that poem is for the other. The poem bends and is stronger for it.

JCW: This is the first collaboration I’ve done with an artist.

KB: And this is the first time I’ve collaborated with a poet.

RT: I don’t know if it’s necessarily our “best” collaboration, but my favorite is the poem “Ode to Miss Donnatella Moss.” It combines our love of history with our love of television (specifically The West Wing). Plus, it’s a lot of fun to read together.

MW: A poem called “New City Ghazal,” for a number of reasons; but mostly because we challenged each other to work our names into the poem and did.

QUESTION 9: Worst? In hindsight, what about it made it so bad?

MA: Things don’t work in collaboratives if personalities are too dominating or large. Josh & I have not experienced much failure as we don’t focus on failure, allow ourselves to get too stuck, or hold lofty expectations over one another’s heads.

JGM: Sometimes the last one in the series. These poems only work if you don’t force them too. It’s like you and your collaborator are in a venn diagram, and you’re constantly edging the poem towards the middle of the diagram. Then you find something that’s kind of already there and you think that’s great. Then it’s just there and it isn’t going anywhere. After that you move on quick.

RT: I don’t know what our worst was. We’ve definitely had collaborative poems that haven’t worked out, but I think they failed for the same reasons that any poem fails, not necessarily because the poem had two poets.

MW: We wrote a poem about NCIS. You read that right. Just because we love the show doesn’t mean other people should care. And that’s all I have to say about that.

QUESTION 10: Was there any pressure to perform?

MA: No performance pressure, and sometimes more risks than in my own writing. True exposure without vulnerability is how I’d define our collaborative relationship.

JGM: Yes. Why else would you want to collaborate with someone?

JCW: The only pressure I recall is a deadline we had to meet several months ago. Otherwise, we’ve been going at our own pace.

RT: I actually found there to be less pressure. If I got stuck, I passed the poem off to Marcus, and he usually came back with something amazing. Having a great poet to work with means you’ve got support.

MW: Yes and no for the same reason. Because Ryan is a hell of a poet whom I admire and trust with my work.

QUESTION 11: Did you offer feedback or critique of other collaborator’s work? Did they to you?

MA: Not really. We also branched out with a photographer, Sparky Campanella, at one juncture. In that process our collaboratives were responsive parallels.

JGM: The most real kind of feedback or critique: continuing to collaborate with someone.

I think we all want to be influenced, and we go looking for influences. The right ones. I’m more intrigued by how my poetry can appear to mutate under the light of someone else’s work—that recessive quality was there all along.

KB: I would say that the entire process of collaboration involves an ongoing feeding-back and discussion about our work.

JCW: Kathy lives in Auckland, and I live in New York. Every couple of months, we have a Skype conversation to discuss ideas about our collaboration and update each other on our current work. Sometimes I offer my response to her new work and sometimes she responds to one of my poems.

RT: We went through a pretty significant editing process of each of our poems, so both of us got our commentary in, which made the poems much stronger in the end.

MW: Of course. Through track changes via Microsoft Word.

↔

Maureen Alsop, Ph.D. is the author of two books of poetry, Apparition Wren, and most recently, Mantic. Visit her online at www.maureenalsop.com.

Joshua Gottlieb-Miller’s work has appeared in Blackbird, A Poetry Congeries, The Journal, Birmingham Poetry Review, Linebreak, Indiana Review, where he was awarded the 2012 Indiana Review Poetry Prize, and elsewhere. Most recently he was a MacDowell Fellow.

Kathy Barry is a visual artist who lives and works in Auckland, New Zealand. In 2012 she was the McCahon House artist-in-residence, followed by a 3-month residency at the Vermont Studio Center. Her work has been exhibited in dealer and public galleries, and artists’ project-spaces across New Zealand. She teaches contextual studies and drawing at MIT in South Auckland. Visit her website at www.kathybarry.co.nz.

Jocelyn Casey-Whiteman is author of Lure (Poetry Society of America 2009). Her poems have appeared in Boston Review, DIAGRAM, Jet Fuel Review, Jubilat, Threaded, among other journals, and she’s received grants from the Association of Writers & Writing Programs and the Vermont Studio Center. She earned her MFA in Creative Writing at Columbia University and now writes and teaches yoga in New York City.

Marie Harris, NH Poet Laureate 1999–2004, co-produced the first-ever gathering of state poets laureate. She has served as writer-in-residence at elementary and secondary schools throughout New England, written freelance articles for publications including the NY Times, the Boston Globe, NH Sunday News, and Corvette Fever. Harris is the author of four books of poetry—the most recent of which is Your Sun, Manny: A Prose Poem Memoir—and is the editor of several poetry anthologies.

Sebastian Matthews is the author of a memoir and two books of poems. He teaches undergraduate creative writing at Warren Wilson College and serves on the faculty of the Low-Residency MFA at Queens University, Charlotte. He is working on a novel.

Ryan Teitman is the author of Litany for the City, chosen by Jane Hirshfield for the A. Poulin Jr. Poetry Prize and published by BOA Editions. His poems have appeared in The Journal, Ninth Letter, The Southern Review, and other magazines. He was formerly a Wallace Stegner Fellow in Poetry at Stanford University and is currently the Emerging Writer Lecturer at Gettysburg College.

Marcus Wicker is the author of Maybe the Saddest Thing (Harper Perennial), selected by D.A. Powell for the National Poetry Series. The recipient of a Pushcart Prize and 2011 Ruth Lilly Fellowship, his poems have appeared in Poetry, American Poetry Review, Third Coast, and Ninth Letter, among other journals. Marcus is assistant professor of English at University of Southern Indiana and poetry editor of Southern Indiana Review.

Each Friday we will publish a new essay, review, or interview for the 32 Poems Weekly Prose Feature, edited by Emilia Phillips. If you have any questions or comments about the series, please contact Emilia at emiliaphillips@32poems.com.

June 24, 2013

Spells Realized

Contributor’s Marginalia: Alexandra van de Kamp on “The Tin Man Full of Bees” by Sarah Crossland

“―Helping the little lady along are you, my fine gentlemen? Well stay away from her, or I’ll stuff a mattress with you! And you, I’ll make you into a beehive.” –The Wicked Witch of the West in The Wizard of Oz

There are few Americans who haven’t seen the Wizard of Oz and been entranced by its caravansary of memorable characters. Although the Scarecrow was Dorothy’s presumable favorite of the group of friends she finds on her way to Oz, the Tin Man holds a special place in the film’s dream-laden plot because of his missing heart and endearing, stilted dance.

The movie is also famous for having been plagued with setbacks during production. Buddy Ebsen, not Jack Haley, was the original Tin Man, but the tin-colored make up used on him contained aluminum dust that ended up coating his lungs. One day, finding himself unable to breathe, he was rushed to the hospital. He was immediately replaced by Haley, with no excuse ever publicly given for why the role had been re-cast (and the aluminum dust replaced with a less lethal aluminum paste). It seems being a tin man has its hazards. Sarah Crossland’s poem takes as its premise the idea that the potential threat issued above by the Wicked Witch of the West (“I’ll make you into a beehive”) comes to pass for the Tin Man. Thus, this poem begins with a spell realized, an alternative plot followed through, and Crossland evokes this spell viscerally on the page in clipped, whirring stanzas packed with music.

The opening stanza of “The Tin Man Full of Bees” immediately snagged me with its texture and density of sound: “The spell erupts in wings—/glass-backed, a crownish/vellum, veins that tickle/ as they climb their way.” I like the idea of a spell “erupting,” as if the poem were a volcanic force, and there is a compressed tension within each of the poem’s stanzas to back up this first impression. The poets I am often drawn to are the ones that trust music, allow the sounds of words to guide them, even to think for them, and Crossland is just such a poet—unafraid to be entranced by the music in her own poems, so we get densely-packed examples of assonance and consonance. The wings are “glass-backed” and the “vellum” of these wings trigger “veins that tickle.” And what does “glass-backed” mean exactly? The assonance of the “a” here lulls the reader into believing the logical pairing of these two words is matter-of-fact, inevitable, yet it remains slightly elusive. The image suggests the thin, easily shattered texture of glass, or the transparency of windows, but it is a textured glass as in “a crownish vellum”—a thin parchment with a raised surface to it (“vellum” comes from the Old French vellin (from veel or veal) since the thin paper was originally made from calf skin). With that use of “crownish,” one also is led to think of the spiked form of a king or queen’s crown, or its ornate, jeweled surface. In just a few words, Crossland has created a multi-faceted, intriguing image. And the transition from “vellum” to “veins” renders the spell intimately physical; the reader is left to think of the inner-itch of those glass-backed wings “as they climb their way.”

Vigorous word choice abounds in this poem and fuels its motion, pushing its mini-plot forward. The bees are “chevrons” that “charge…motor-fuzzed, from the heart” and the internal rhyme meshes ideas intimately together when the Tin Man laments his condition and wishes he “were made/of meat instead of metal.” Crossland chooses apt imagery to make her point, such as the idea of bees as “chevrons.” The military insignia or “v-shape” this word implies mimics well the stripes of bees and how they, themselves, are members of an intricate hierarchy, assigned their roles and tasks. Moreover, with word choice such as “motor-fuzzed,” the textured presence of these bees inside the Tin Man is clearly articulated. As I read, I can sense the motion of these bees, their staggered dispersal throughout the Tin Man’s body. Is he being internally re-written as they move within him, a palimpsest the bees’ wings print their moving weight upon? While moving through the poem, I find myself wanting to dream along with these clipped, fast-paced stanzas and add my own musings to them.

And these stanzas seem hive-like—their shape one of a pruned, disciplined spinning. Crossland relishes her line breaks and treats many of them as little cliff-hangers, building mystery, speed and suspense into her poem. I often find that poets with an ear for music rarely neglect the opportunity a line break offers them. Crossland writes with a nervy sense for how to use the white space of the page. In the third stanza, we have the line: “I once loved a forest girl/who kissed me with a twister,” and the reader is left, momentarily, to ponder the twister as background to this girl and her kiss. (The gray, spiraling funnel of the tornado as background in The Wizard of Oz is well-stamped on my childhood imagination.) But with the next line, we read “in her lips,” and the twister morphs into an internal one—what the girl carries inside her and bestows upon those she encounters. Here, the Tin Man confesses that the kiss felt “Counter-/clockwise, the opposite/of time. I am a hive.” The repetition of the long “i” sound in “wise,” “time” and “hive” stitches these words tightly together and begins to suggest that a kiss could be “the opposite of time,” its own spell of sorts. Such tense music and suspense at the ends of lines energizes the poem and helps create a spinning, even careening sensation as the reader finds his or her assumptions periodically upended. Another “cliffhanger” occurs later in the fourth stanza: “Their stripes/the color of a morning/fruit that sings as its citrus/bites.” Thus, the bees’ stripes are not just the color of “a morning” as the reader might be led to first believe, but the color of “a morning/fruit” that sings and bites. Almost like mini-page turners, these line breaks ask the reader to read on—to “turn the page” in poetic terms by finding the resolution of the image on the next line. This clever, thoughtful use of line breaks builds a nervous energy into the poem and propels the reader forward, as if Crossland wanted to re-enact on the page a hive of image and sound.

Crossland’s rich and textured use of sounds continues throughout the poem, and you wonder, as the reader, if the ‘s” in “sings” helped her finds the “s” sound and image in “citrus” and if the “i” in “bites” led her to “strikes,” and then to “out my pipe.” The poem is dreaming its own dream now—thinking in sounds, as all my favorite poems do. The closing line of the poem, “in the hum I come alive,” offers an ambiguous sense of closure, since the reader sees that this spell offers the Tin Man not only suffering, bees that “gnaw and strike,” but also a vivacity, an astringent vibrant taste of life. The physical “hum” of the hive awakens him to both pain and to a renewed alertness. In the film, the Tin Man is given a ticking clock for a heart, but here, in this plot, an internal, “motor-fuzzed” eruption is bestowed upon him, a “tickle” in his veins and a citrus that bites and sings. The reader is left to ponder which was the better, more potent result in the end—perhaps this more uneasy version of the heart, this uncontrollable, hypnotic hum Crossland invokes on the page.

—Alexandra van de Kamp

Alexandra van de Kamp lives in Stony Brook, NY, with her husband and is a lecturer at Stony Brook University. She has been previously published in journals such as: Court Green, Salt Hill, Crab Orchard Review, Washington Square, River Styx, Meridian, The Denver Quarterly, The Prose-Poem Project and Connecticut Review. New work is forthcoming in Thrush Poetry Journal and The Cincinnati Review. A full-length collection of poems, The Park of Upside-Down Chairs, was published by CW Books (WordTech Press, 2010), and her most recent chapbook, Dear Jean Seberg (2011), won the 2010 Burnside Review Chapbook Contest. Recent poems have been featured on VerseDaily, and she is currently at work on a second book entitled “Kiss/Hierarchy.” For six years she lived in Madrid, Spain, where she co-founded and edited the bilingual journal, Terra Incognita. You may see more of her poetry and prose at her website: www.alexandravandekamp.com.

June 21, 2013

Weekly Prose Feature: “Subject to Distortions: An Interview with Amy Beeder” by Emilia Phillips

Amy Beeder is the author of Burn the Field (Carnegie Mellon University Press, 2006) and Now Make An Altar (2012). Her work has appeared in Poetry, Ploughshares, The Nation, The Kenyon Review, The Southern Review, AGNI, and other journals. She lives in Albuquerque and has taught poetry at the University of New Mexico and Taos Summer Writers Conference. She has received the “Discovery”/The Nation Award, a Bread Loaf Scholarship, a Witness Emerging Writers Award, and a James Merrill Residency. She has worked as a freelance reporter, a political asylum specialist, a high-school teacher in West Africa, and an election and human rights observer in Haiti and Suriname.

Amy Beeder is the author of Burn the Field (Carnegie Mellon University Press, 2006) and Now Make An Altar (2012). Her work has appeared in Poetry, Ploughshares, The Nation, The Kenyon Review, The Southern Review, AGNI, and other journals. She lives in Albuquerque and has taught poetry at the University of New Mexico and Taos Summer Writers Conference. She has received the “Discovery”/The Nation Award, a Bread Loaf Scholarship, a Witness Emerging Writers Award, and a James Merrill Residency. She has worked as a freelance reporter, a political asylum specialist, a high-school teacher in West Africa, and an election and human rights observer in Haiti and Suriname.

Emilia Phillips: Your poems in Now Make an Altar always excite me initially with their subject, second with diction and sonics, and third, and perhaps most importantly, with syntax and form. One poem can sustain a great deal of maneuvering, from short subject-verb-noun constructions to complicated sentences that unpack and nuance their meaning through successive clauses; from fragments to catalogues; questions to one-word imperatives. For readers to get a sense of this, here’s an excerpt from “Country Life”:

They came for land. For hog-high wheat to Dixon, Weeping

Water, Garland Falls;

came to Midland hamlets, made their farms from bogs & marshes,

fens & bottomland: immigrants from Krakow, Darkov, Laśko

who fled famine, coming wars or the Eastern factories, left

city rivers thick with indigo & slaughter’s crimson, tenement

air: TB & boiled tubers, fled the bellows & gutter cast, sawdust

& accident;

left forever what Riis called the strip of smoke colored sky so that

their children’s children might grow up corn-fed, reverent,

thrifty; that they might join 4-H & raise lambs, might

crochet & macramé; might play the clarinet or their fathers’

accordions, always

optimistic despite the blizzards & drought, locust & blight.

Where there’s space to push the earth aside: that’s the place

to raise a child—

There’s so much tension between your sentences and the way they carry themselves over the page. In “Country Life,” in particular, “They came for land” gives us the scope of the poem, the frame, whereas the long, semi-coloned sentence fills in the details within that frame and begins to identify what’s at stake. The sentence provides a texture, a sweeping movement that mimics the immigration of the people and the subsequent evolution of their culture. In that way, your form and syntax provide us with, what I’d call, physical information—an experiential understanding of what’s happening.

I imagine this takes many drafts to get right. Would you mind speaking to your drafting process, especially in relation to finding the appropriate and propulsive syntax for your poems?

Amy Beeder: You’re right that “Country Life” went through many drafts, more than usual. I wanted it to sound (as you said) both “sweeping” (fled famine, coming wars) and very particular (the reference to Riis, macramé, etc.). I also wanted it to seem not just layered but crowded, somehow; I imagined the masses of people disembarking at Ellis Island and, later in the poem, more contemporary images of confusion or chaos. It turned out that was difficult to do and still maintain clarity and movement. One thing I finally did in the section that you mention was to use a kind of “ladder” of repeated and/or similar sounding verbs : came/came/made/fled/left/fled/left. I thought short verbs might unobtrusively both ground and clarify the poem and push it forward.

As far as syntax and my drafting process, generally I am only thinking about whether the poem “sounds right” to me. Of course this doesn’t just involve purely sonic elements but constant arrangement and rearrangement: giving some phases more weight than others, repetition, dividing the subject or verb to create tension; choosing an imperative or interrogative. Still it’s something done by ear and not with a very conscious consideration of syntax, if that makes sense. In The Art of Syntax Ellen Bryant Voigt describes variance of syntactical patterns as being “like the engine of a train . . . pushing some of its boxcars and pulling others.” It’s a splendid metaphor, and useful: especially for students whose eyes tend to glaze over when you start using words like “elided,” or “subordinating pronoun.” And who can blame them?

EP: What you said about a poem “sounding right” leads me to think about the relational tension between tonal levels in Now Make an Altar. Despite their clarity, your poems devise a lush language-scape, even when you primarily use idiomatic diction; that said, you’re not shy of combining this with superannuated interjections like “O,” Latinate or archaic words, King Jamesian turns of phrase (“askew in the bow’s pitch Lord”), and outside/found texts—sometimes all in one poem. Some poets would say that “sounding right” in a poem means sounding conversational; others balk and insist that poetry deserves the best language the brain can buy. I often find that these individuals have different language backgrounds: the first, perhaps, in a community where interpersonal interaction and communication is the fundamental vehicle for language; the second, however, might have first encountered language in a stylized ritual or religious context. For me, your poems negotiate with and within both of these tonal modes. Would you be able to talk about some of your first experiences with language and/or the writers and texts that might have shaped your orientation(s) toward language?

AB: That’s a fascinating question and one I’m not I sure can answer satisfactorily. But here goes: According to family lore I read early, (my mother was a first-grade teacher with strong opinions about children learning to read early and about the evils of television), and before I could read would obsessively turn the pages of books or magazines and “pretend” to read, often aloud. I don’t think that’s unusual; both my daughters did the same thing, and I think a lot of children do. Neither I nor my daughters encountered much language in a religious context, but I wonder if enough extra emphasis on text early on might count as a stylized or even ritual encounter. I know I was always encouraged to read stuff (Shakespeare, T.S. Eliot) that was clearly beyond my level, and so learned to enjoy texts/words/phrases without completely understanding them. When I saw “Under Milkwood” in middle school I didn’t get it, but I loved it. I think phrases from that play, the rhythm of Dylan’s language, would have stayed with me even if I hadn’t reread it many times. Nabokov had a similar influence. That kind of thing may account for some of the sound over sense in my work.

As far as more conversational (or narrative?) modes: my father is a wonderful storyteller. A number of my poems are based on his stories: “Black House,” “Photograph in a Montana Bar,” “The Book of Lost Railroad Photographs,” etc. Those poems always depart considerably from the original story, but then my father’s stories always changed, too: they were exaggerated, details were added and subtracted, new characters (complete with accents) were introduced. My poem “Train” refers to his story of a runaway train in Cheyenne in 1950. The train is the central image, but really the poem is about how histories always change, not just through re-telling by others, but even in the teller’s mind, perception and memory. Just for fun, I called my Dad today and asked him to tell me the runaway train story again. Sure enough there were new details, including the expression “in the big hold” which I surely would have used in the poem if he’d said it before.

Where was I going with this? Maybe that even conversation, story-telling and conversational poetry are subject to their own stylizations and distortions.

EP: Many of your poems enact some sort of process of making: a fire in “The Charges Are Stalking & Arson,” a sale in “Harold von Braunhut, Distributor of Sea Monkeys, Promises Instant Life,” folk art in “Darger’s Colors,” etc. By taking on the idea or process of making, does a poet automatically engage in ars poetica?

AB: Sure, any kind of “making” in a poem will suggest ars poetica to some readers, and I’m one of them. When Dana Levin taught (all too briefly) at UNM, I had my students read her poem “In Honor of Xipe.” I read it at least in part as an ars poetica, and suggested that to my students. Later when Dana visited my class and someone brought that up, she was surprised; she never thought of it as one. But does that mean it’s not? I think whether a poem engages in ars poetica is as much up to the reader as the poet. (Having said that, I considered “The Charges Are Stalking and Arson” and “Harold von Braunhut” as ars poetica(s), but not “Darger’s Colors.” Which is pretty odd because Darger is the truly ekphrastic one).

EP: I once had a professor tell me that if I was ever stuck in a poem to address a specific person. His suggestion was that an addressee would orient the poem toward its stakes. Because the collection harbors the trope of making, you often employ the imperative and, therefore, take on an implied or overt “you.” How does direction/insistence as well as an addressee guide your writing process?

AB: That’s funny, because I once had a poetry professor tell me to avoid second-person address at all costs. Obviously I didn’t take his advice. It’s always come naturally to me. I like the urgency, the insistence, as you call it. I agree with your professor that it’s a useful way to find the heart of your poem or stir things up at least, or change the tone. But for me I think also it’s a way to “revise” life, redress and revisit, apologize to or mourn people, or tell them off. Although for me “you,” does occasionally mean me, most often it’s a very specific person, who then of course may shift or bifurcate as the poem develops. The whole poem and the addressee may change but that initial energy/urge hopefully remains.

EP: I’m interested if, when revising, you ever feel that that initial energy/urge has changed. Do you let the poem go where it’s headed? Scrap it? Return a few drafts? Start over?

AB: Any of the above can happen. I do always try to let the poem go where it’s headed, because for me the subject and direction of the poem often change, even dramatically, without the poem losing what I think of as its essential energy. And I try to follow my ear: I agree with Richard Hugo that it’s usually a disaster to try and “push words around” to say what you want; rather, they should push you around. (Still I always try to keep an early draft, just in case). Rarely do I totally scrap a poem. If I can’t make it work I just leave it in a file called “Rough,” and revisit it occasionally; sometimes I’ve come back to those poems and have suddenly been able to make them work. What I’d call “starting over” usually involves a change in point of view and/or or a significant structural (stanza, line length) change. Or the poem’s “meaning” changes entirely, becomes something I didn’t see before, surprises me.

EP: What’s the first and last poem of Now Make an Altar that you wrote? How did those poems open up the collection, shape it, and then complete it for you?

AB: The first poems I wrote were the “letter” poems: H, D, and X; I think X was the very first. I was reading a book on the history of the Latin alphabet and was fascinated by how letters developed and changed, by their Greek, Etruscan and Phoenician origins, etc., but even more by the theory that some shapes of letters may have had had meanings. Does “X” come from the Phoenician “samekh” (fish) because it looks like bones? Does “D” come from a door (an open tent flap), or the shape of a breast? For me this came down to the basic question of how language carries meaning.

I suppose those poems might have shaped the manuscript because so many of the other poems address that same question. How do we “make” things out of marks on a page, or speech? I don’t think the poem “Unstack the Dams Now Make an Altar” was the very last poem I wrote, but it was near the end, and in a way speaks to same idea. When we were very young, my brother and I used to play by trying to conjure things up in the ravine behind our house (I’m not sure what we expected to see: protective spirits, fairies, the rumored ravine-dwelling ghost?) with potions, patterns of mud and sticks, and sacrifices—usually of Barbie Dolls. There’s still something about writing poetry that reminds me a little of that play. Weird, huh?

EP: The idea of the poet being at play is both an image of joy and desperation—and entirely accurate. I once had a student ask a poet with whom my class was Skyping if he’d ever burst into tears while writing a poem. The poet responded that he hadn’t but had burst out laughing. I think students and beginning poets initially have the notion that writing poetry has to be a torturous, heart-wrenching affair; I’ve found, however, that I experience the breadth of “real life” emotions while writing, including levity. What are the dangers, if any, risked by a poet who takes their writing and process too seriously?

AB: Ah, the beginning student who wants it to be torture! Fun. That usually passes. Usually. I do get impatient with the professionals who still introduce their poems with assurances of how serious the following poem is, how important, how sacred, how transformative, how inspired by the muse. The dangers risked by that? Sounding boring and pretentious.

Not that I have anything against introducing poems, especially at readings, where the audience can’t necessarily reread the work right away. I do that a lot. But intros should be informative, grounding, helpful in terms of placing the audience, not telling them how impressed they should be.

EP: To some degree, it seems that being a poet these days is as much about visibility (where one teaches, what contests one’s won, etcetera) as craft. What’s your conception of the ideal life of a poet?

AB: Warning: this is a very personal issue for me. Though I have been extremely lucky with publications, I am an outsider in PoBiz. I don’t have an MFA, “only” an MA in literature. I have never held a tenured position; the years I taught at UNM I was adjunct. In fact, until I won The Nation/Discovery, I taught freshman comp and technical writing. That speaks to your point about visibility: winning that prize suddenly qualified me to teach poetry (!), albeit at about one-eighth of what tenured professors got to teach the same class. In the end my publications and student evaluations meant absolutely nothing to the UNM English Department. For years I taught for disgracefully low wages because I thought somehow as a poet I had to be associated with a University. Now I write freelance three hours a day in a field unrelated to poetry and make more money than I did teaching. I work on my third book and another collaborative project, fix up my house, and hang with my daughters. So for me the ideal life of a poet is what I have right now (or would be if I just had another hour or two every day to write poetry).

EP: Would you mind talking a little bit about your experience living abroad as a human rights observer in Haiti and Suriname and a high school teacher in West Africa? Were you writing poetry during that time? In those locales, did you encounter poetry?

AB: I never wrote poetry when I lived abroad. I did keep copious journals. Now I write poetry and never anything journal-y. All the places I lived abroad (except for France) were all, for various reasons, pretty extreme on a daily basis, and I think I wrote because I didn’t want to forget anything that happened—but still I should have written more. Suriname in particular is a blur. I’ve never thought much before about whether I encountered poetry in those locales. But now that you mention it, I think about how my Mauritanian family, my students, my neighbors, people I lived with for almost three years, really lived language. Griots would visit: chant, sing, pray, tell family histories; everyone in my family spoke Fulani, French, Arabic and at least some Soninke, Wolof and English. My Lycee students were the best language learners I’ve ever seen: they could watch the weekly (always foreign) movie at the outdoor theater and pick up 20 or 30 English or Chinese words or phrases without even trying. And then make puns and plays and games out of them. Everything endlessly repeated and changed. Poetry? Everything a joke. My family taught me Fulani and claimed to want to teach me Arabic, but then only taught me the most obscene Arabic phrases. I miss them.

EP: I’ve often heard the complaint that poets who teach in academic don’t live in “the real world.” This seems to me a criticism of integrity and authority. Should poets seek to retreat from academia and po-biz once and a while? Does it depend on the poet?

AB: I’d never say academia isn’t “real world” It’s its own real world. Teaching, and administration, if you do them right, are very hard work. And if University departments are rife with sometimes exaggerated drama and intrigue, so are many offices, and, I assume, factories, restaurants, etc.

That said, it might be interesting to see more poetry by people who don’t work in academia all Just for variety. Right now I’m thinking of two very idiosyncratic poets: Atsuro Riley and Hailey Leighthauser, both of whose work make me sit up and take notice right away because it was just so weird and exciting. Neither of them has every worked in academia and I don’t think either has an MFA.

EP: I’m fascinated by the action that one can “live language” because it also implies its opposite—not living language—or, at the very least, degrees of it. It seems like Westerners, particularly Americans, see “language,” artful and meaningful communication, to formal and/or important occasions and spaces (like poetry) and, instead, see information as the medium through which we communicate on a daily basis.

Do you feel that the English language’s potential isn’t realized by most Westerners, particularly Americans? How so? Is it possible to teach the appreciation and practice of artful and meaningful language use on a daily basis?

AB: I really hesitated before writing that phrase “lived language.” Of course everyone who speaks, reads or hears, lives language. I guess what I meant was what I saw as a level of comfort (and just pure delight) with spoken language in particular. My students in Kaedi never missed a chance to talk in class, give their opinions, or (brilliantly, damn them) mimic me. Naturally this made classes chaotic, but when I hit upon the idea of letting them do doing “plays” (short dialogues in English) in front of the class, things improved.

Yet speaking in front of the class is the very last thing most American students want to do. Some will take a failing grade rather than do it.

. . . Off the subject again. Yes, I do think the possibilities of English are not realized by most Americans, but that’s probably true of almost every language almost everywhere. As you said, it’s become dominated by “communication.”

EP: Have you done any translation? If so, would you mind telling us a little bit about the process? Do you think that poets who speak other languages have an obligation to translate poetry into English?

AB: I’ve wanted to do translation, but, no, I haven’t. One issue for me is that the other languages I speak or once spoke I didn’t learn in a classroom, so my speech is far better than my writing or reading. That’s true even with French.

An obligation to translate? I guess I don’t feel one because I know there are people so much more qualified. Though I would love to translate Pulaar/Fulani poetry or stories, just because they’re so cool and there probably aren’t that many in English, I would need a lot of help to do it.

EP: As poets, we’re aware of the possibilities of language but we are also aware about language’s limitations. Is there a subject, image, or idea that you’ve never been able to express or fear you will never be able to express? What keeps you writing even though your medium isn’t perfect?

AB: Words always fall short. Like most writers, there are things I don’t write about directly but are always there; after awhile you realize this perpetual raging subtext is one engine of your work. Dylan Thomas said the “best craftsmanship always leaves holes and gaps in the words of the poem so that the something that is not the poem can creep, crawl, flash or thunder in.” Or, to take the other view that experience is what “fails,” Gunter Kunerts: “That’s why I write; to bear the world as it crumbles . . . ”

Matthew Olzmann*: Frank O’Hara once said, “Only Whitman and Crane and Williams, of the American Poets, are better than the movies.” If you were to write a similar list, what poets would you include?

AB: After mulling this over for a few days, I decided not to give a list of names. They would be probably known to many of your readers anyway. (Sorry, Matt!) Of course there are poets I admire, poets whose books I buy, etc. But I think what I like best about American poetry right now-and why it’s usually better than the movies- is that I keep finding (in all kinds of journals) amazing poems by people I’ve never heard of. I love it.

EP: Now, Amy, provide us with a question for the next interview.

AB: As a poet, who was your important teacher?

↔

Emilia Phillips is the prose editor of 32 Poems.

*As a part of our interview series, we ask each interviewee to provide us with a question for the next interview. To view Matthew Olzmann’s interview, go to May 31st’s Weekly Prose Feature: “Usually a Window, But Occasionally a Stage: An Interview with Matthew Olzmann”

Each Friday we will publish a new essay, review, or interview for the 32 Poems Weekly Prose Feature, edited by Emilia Phillips. If you have any questions or comments about the series, please contact Emilia at emiliaphillips@32poems.com.

June 17, 2013

A Rabbit’s Foot

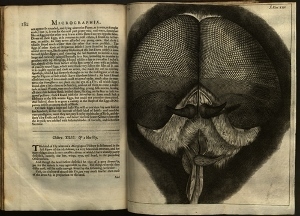

Contributor’s Marginalia: Amit Majmudar on “Fly” by Richie Hofman

There’s a “20 under 40” list The New Yorker has for novelists, but if there were a “15 under 30” list for poets, Richie Hofmann would be on it. It seems the Poetry Foundation agrees with me on that.

“Fly” begins in Pliny and ends in love. Not a bad natural history for a poem.

“Fly” begins in Pliny and ends in love. Not a bad natural history for a poem.

The compound Epcot-center eye of the fly is the perfect rabbit’s foot against blindness. I would keep a cockroach against death.

The title, “Fly,” refers both to the insect—and the “flighty” lover. Daphne flies from Apollo. Tempus—fidgets—

Verse itself is an “elaborate ritual” against the fleetingness of utterance. Hoffman is capable of elaborate rituals indeed: cf. his poem “Illustration from Parsifal” in The New Criterion, which is a preternaturally perfect example of anagrammatic rhyme. Formal flexibility is a greater virtue than formal ease. Hoffmann displays both in his rapidly growing body of work.

—Amit Majmudar

Amit Majmudar is a diagnostic nuclear radiologist who lives in Columbus, Ohio, with his wife and twin sons. His poetry and prose have appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, The Best American Poetry anthology (2007, 2012), The Best of the Best American Poetry 1988-2012, Poetry Magazine, Granta, Poetry Daily and several other venues, including the 11th edition of the Norton Introduction to Literature. This is his third appearance in an issue of 32 Poems. His first poetry collection, 0′, 0′, was released by Northwestern in 2009 and was a finalist for the Poetry Society of America’s Norma Faber First Book Award. His second poetry collection, Heaven and Earth, was selected by A. E. Stallings for the 2011 Donald Justice Prize. He blogs for the Kenyon Review and is also a critically acclaimed novelist. Visit www.amitmajmudar.com for details.

Amit Majmudar is a diagnostic nuclear radiologist who lives in Columbus, Ohio, with his wife and twin sons. His poetry and prose have appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, The Best American Poetry anthology (2007, 2012), The Best of the Best American Poetry 1988-2012, Poetry Magazine, Granta, Poetry Daily and several other venues, including the 11th edition of the Norton Introduction to Literature. This is his third appearance in an issue of 32 Poems. His first poetry collection, 0′, 0′, was released by Northwestern in 2009 and was a finalist for the Poetry Society of America’s Norma Faber First Book Award. His second poetry collection, Heaven and Earth, was selected by A. E. Stallings for the 2011 Donald Justice Prize. He blogs for the Kenyon Review and is also a critically acclaimed novelist. Visit www.amitmajmudar.com for details.

June 1, 2013

32 Poems 11.1 On its Way to Fine Mailboxes Everywhere

The latest 32 Poems shipped yesterday, so American subscribers should start checking their mailboxes the first of next week. In this number we feature new poems from Chad Davidson, Anna Journey, Amit Majmudar, Caki Wilkinson and nearly two-dozen other poets as fine as you’ll find anywhere. The issue has been a joy to put together and we can’t to share with readers. Let us know what you think, and of course if you don’t yet have a subscription, now’s the time to remedy that. Follow this link to get your copy on its way.

In the meantime here’s a sneak peek to whet your appetite:

The Art of Reading

by Rebecca Morgan Frank

Candlepin, lynchpin, safety pin become

death by fire, hanging, stabbing. Cocktail

becomes the plumage of a male bird

staring me down in the dirt. Napkin

is a sleeping cousin drooling on my bed:

it’s noon. Heaven-sent, you smell like

the gods. A word can sock you with a kick,

mock you in a turtleneck, hiding its intent.

Barely. Comedy is two-faced, watching.

Come on, give it a try. Hot dog? Wild

flower? Everything is sweaty and dancing

when you bring back the inanimate.

Looking into its violent core, dormant

but burning to be read wrong, read right.

May 31, 2013

Weekly Prose Feature: “Usually a Window, But Occasionally a Stage: An Interview with Matthew Olzmann” by Emilia Phillips

Matthew Olzmann is the author of Mezzanines (Alice James Books). His poems have appeared in New England Review, Kenyon Review, The Southern Review, Inch, Gulf Coast and elsewhere. With Ross White, he coedited Another and Another: An Anthology from the Grind Daily Writing Series. He’s received fellowships and scholarships from Kundiman, the Kresge Arts Foundation, The Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and the Kenyon Review Writers Workshop. Currently, he teaches in the undergraduate writing program at Warren Wilson College and is the poetry editor of The Collagist.

Matthew Olzmann is the author of Mezzanines (Alice James Books). His poems have appeared in New England Review, Kenyon Review, The Southern Review, Inch, Gulf Coast and elsewhere. With Ross White, he coedited Another and Another: An Anthology from the Grind Daily Writing Series. He’s received fellowships and scholarships from Kundiman, the Kresge Arts Foundation, The Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and the Kenyon Review Writers Workshop. Currently, he teaches in the undergraduate writing program at Warren Wilson College and is the poetry editor of The Collagist.

Emilia Phillips: First of all, I’d like to praise your uncanny ability in panning for gold when it comes to finding subject matter—a skill that also insists some pretty killer titles as well, like “Man Robs Liquor Store, Leaves Resume” and “NASA Video Transmission Picked Up By Baby Monitor.” How do you locate what you’re going to write about? Do you keep a journal of interesting things? Do you immediately set out on the poem or do these subjects stick with you for a while before you write? Or do you make it all up?

Matthew Olzmann: Thanks, Emilia. I try not to be afraid of my own bad ideas, and let’s face it: both of those poems had the potential to be big failures. While I’m equally likely to “make it all up”—and I often do—these titles, in both instances, were initially triggered by actual “news” stories, and the lines that followed those titles were mostly speculation, invention, and answers to questions I asked myself about some imagined situation.

The challenge in that type of writing is to transcend the bombast of the tabloid-headline-esque title, to build upon the novelty of that opening moment, and to create something that somehow builds upon that initial moment of surprise. When I say, “I try not to be afraid of my own bad ideas,” that’s because I’ve written poems that begin in a similar fashion, but they go nowhere. Actually, that’s usually what happens, but I keep writing them; in fact, I’m excited to write them. I’m drawn to the odd, freak-show moments of American life, and if something surprises me or puzzles me or leaves me feeling the slightest bit of awe—an event, image, or a piece of language—that’s a place or a subject that is often roiling with possibilities.

So, I guess the answer to part one of this question is: a lot of trial and error. I try to write about things especially when I’m not sure if I’ll be able to actually turn them into poems. And often I can’t, but if I write enough of them, a couple might make it through the gap. Sometimes, when I’m lucky, I’ll have a plan when I sit down. But most often, it’s more of a notion, a single image, a word. Then a lot of making things up. A lot of guessing. A lot of questions that begin with “what if . . . ”

I usually don’t keep a journal of ideas or notes because I try to write everyday. This pretty much wipes out the reservoir of backup ideas, thus rendering the journal a little bit useless. But this also frees you to relentlessly attempt the absurd. When you’ve got nothing in front of you but a blank page (and the terror that it will stay blank), you’re willing to try to write about anything, no matter how odd, or how strange.

EP: Your poems, for me, insist their entireties, their unabridged arcs. It’s impossible to locate pith and difficult to quote only a couple of lines at a time as they often function dependently on one another for narrative, syntax, nuance, or gravity. When you do arrive at a gesture of statement or commentary, it alloys the abstract with image, eschews platitudes or takes them to task as in “The Man Who Looks Lost as He Stands in the Sympathy Card Section of Hallmark” where we have a speaker who addresses a/the poet in the second person:

you want to place a hand on his shoulder, say,

It’ll be okay. But you don’t.

Because you also look like a crumbling statue

narrowed by rain, because you too have been abandoned

by language and what’s there to speak of or write

among so many words. There are not enough words

to say, Someone is gone and in their place

is a blue sound that only fits inside

an urn which you’ll drag to the mountains

or empty in an ocean with the hope

that the tide will deliver a message

that you never could. Because even those words

would end like a shipwreck at the bottom

of clear water.

Words fail us, especially those in such bromides that appear on greeting cards. How do you overcome words’ ineptitudes, especially when taking on subjects with gravitas like death or hunger? When writing, do you ever feel that you’re working with subpar materials (the English language)?

MO: While it may seem contradictory, we often turn to poetry specifically because words fail us. There are limitations to language, things we can’t express adequately and things we can’t express at all. So we turn to metaphor; we turn to poetry. The poem, when it works, doesn’t just declare an emotion, it makes that emotion tangible; it allows us to actually understand that experience with greater speed and clarity. An elegy, for example, doesn’t merely say, “I’m sad,” or “I have lost someone.” The job of the elegy isn’t to simply “announce” grief, but to make it palpable so that we can comprehend its depth and magnitude. This is the paradox: the “subpar materials” are the tools of this trade exactly because they are subpar. So we try to combine them to make something new, hoping that the new expression will work more effectively. We don’t have a word to sufficiently and accurately express longing, or loss, or desire, or any of the countless and subtle variations within those emotions. If we had such a word, we would repeat it over and over, without end. In the absence of such a word, we try to “overcome words’ ineptitudes” through metaphor, through figurative gestures that stumble toward making these abstractions less abstract. For me, it’s impossible not to feel the insufficiency of language when trying to build something new out of it. However, those same flawed building blocks simultaneously leave me awestruck and stunned. Maybe Jack Gilbert says it best in opening lines of “The Forgotten Dialect of the Heart”:

How astonishing it is that language can almost mean,

and frightening that it does not quite.

EP: Seeing your answer, I return to this moment in “A River, Briefly Parallel to an Eight-Lane Super Highway”:

Some would correct me here, say:

No, that’s not a “river,” but a “stream” or a “brook.”

But the river doesn’t care about its name,

it would never correct you

Here, you seem to take on two issues: first, the limitation of language, specifically of the words “river,” “stream,” and “brook” in describing the body of water; and, two, a potential challenge to your precision. Since many of us are products of workshop, I can’t help but wonder if we, as readers, have been rewired to automatically look for fault in what we read. What are your thoughts on this? Do you feel any obligation to head off this kind of criticism and, if so, how would you go about doing this? Any advice for us on how we should approach reading?

MO: I think there’s some truth to the idea that the context in which we view something might impact how we view it. Maybe we’ll experience a poem differently if we first encounter it in a magazine rather than in a classroom. However, my first reaction as a reader isn’t a critical one in terms of “these parts aren’t working correctly,” but an emotional one: I am filled with joy, saddened or bored. This in itself, can also be a form of critique, I imagine. But in general, the reader in me is very different from the writer in me. I came to the writing of poetry, only after developing a love for the reading of poetry. I had to train myself, later, to unite these different impulses—to read as a writer—and that was the main reason I went back to school after years away from it; I wanted to learn how that emotional reaction I have as a reader is produced by very specific strategies employed by the writer. Even now, in my most critical moments, I think I tend to approach good writing with a sense of awe. And in my most analytical readings of a poem, I’m rarely trying to find the flaws of a piece but simply struggling to understand how the various mechanical elements contained in that piece work together (or don’t) in order to create a particular response in the reader. I don’t think there’s a rule for how people should read. We all read different things for different reasons and therefore have unique expectations of the experience. We want it to entertain or teach us something. We want to escape from our lives for a moment, or we long to learn the names of trees. But I hope as writers, we occasionally remember the reverence we had for books before we set out to write them.

EP: Incredible answer, Matt, and I think your stance of generosity in reading and toward the readers’ needs also reveals itself in your use of tone. Your poems have a tonal generosity: they don’t stagnate emotionally but, rather, continually develop and ebb so that in a single poem, like “For a Recently Discovered Shipwreck at the Bottom of Lake Michigan,” a long poem in the form of an epistolary apostrophe, we encounter the absurd, the meditative, the unsettling, hilarious, and devastating. A sample:

April 6th, 2010

Dear Shipwreck,

So what’s it feel like to have everything inside you still “intact”? That’s what I want to feel like. But I’ve actually never felt my “insides” at all—I think they’re positioned in a way that keeps them from banging around. When I was small I would jump up and down for hours trying to make them Rattle. Nothing. I am an empty rattle.

P.S. Please write back.

May 9th, 2010

Dear Shipwreck/Dear Metaphor for God,

I was thinking of Bashō today, and I wrote you the following poem:

O, Shipwreck, untouched by moonlight,

molested by billions

of writhing quagga mussels.

What do you think? Is “moonlight” too heavy-handed? Not believable enough? Let me know your thoughts . . .

June 29th, 2010

Dear Mister-Too-Good-to-Write-Anyone-Back,

Fuck you, boat. I don’t care if you didn’t like that poem. That’s no excuse for ignoring my letters. I will say this real slowly for you:

Write. Me. Back. You. Dick.

The tour de force of your poems resides not within the intensification of one flat concern but in the tension between many, sometimes conflicted, concerns. I often leave your poems feeling as if you haven’t prescribed an emotion for me, as so many poets try to do, but rather have introduced a nucleus of questions, swirling with positive and negative charges.

How conscious are you of tone when you’re writing the initial draft and then revising? Do you find it easy to vary tone if you work on a poem over a long period of time?

MO: I’m semi-conscious of tone when writing a first draft, and very conscious of it when revising. Tone being the speaker’s attitude toward the subject matter of course informs the reader’s relationship toward the subject matter as well. Ellen Bryant Voigt says that tone is “what the dog registers when you talk to him sternly or playfully: the form of the emotion behind / within the words. It’s also what can allow an obscenity to pass for an endearment, or a term of affection to become suddenly an insult.” In an initial draft, I’m not always aware of the numerous factors that can shape that “emotion behind / within the words.” I’m only aware of the words themselves. In terms of later adjustments and creating tonal variation: I haven’t found any specific formula for how long I need to work on a poem to get these things right. In general, it’s easier for me to revise if I haven’t looked at the poem for a little while. Sometimes that means a couple of days. Sometimes it might be a few years. The challenge in revising is to achieve an outsider’s level of impartiality. You’re trying to read your poems objectively while essentially guessing how a reader (other than yourself) will experience what’s been written. Then you make (what you hope will be) the proper alterations.

EP: I’ve often found that students have a hard time at first removing themselves from the poem to create that kind of “outsider’s level of impartiality” that you mention. As a mentor or teacher, how do you help a student get to that level? Do you have specific exercises or advice that you give them? When and how did you first get there?

MO: That’s something that I’m still working toward, but, to some degree, that perspective—that particular brand of objectivity—comes from reading a lot. As a writer, you might be able to make a reasonable guess as to how a reader will respond to a poem or part of a poem, because you remember how you (as a reader) have responded to similar strategies, moments, and elements in poems you’ve read. We know the impact of words only because they’ve impacted us. Frequently, students who are new to poetry haven’t read much poetry. So what we try to do is get them reading and show them how to learn from those readings. You try to simplify, to look at one device, craft element or strategy at a time, and then help them articulate how whatever effect they’re drawn toward has been achieved in the poem that we’re studying.

EP: Are there any particular writers that you return to if you’re stuck on a poem or a project? If so, what about their writing motivates you?