Deborah Ager's Blog, page 7

March 11, 2013

Precision that Defined Arachne

Contributor’s Marginalia: Hannah Sanghee Park on “Downdraft” by Carol Light

LOOM

Reading Carol Light’s marvelous “Downdraft” puts many good words in mind, but loom seems most apropos. Here is one controlled by both the measured foot and the careful hand. The line-by-line time-lapse of a tapestry narrative: the deft weft, the warp’s wrap, each line precise in itself but the sum of it being the awe of it. This the first metamorphosis. Then the second: the creation would green the eyes of the gray-eyed one. And the third: we can expect Light to S.O.S from her new spinneret.

MENAGERIE

It was precision that defined Arachne: her impeccable craft, her hit too close to Olympian home. Everything biotic in Light’s poem has deliberation—she has created a world of specificity, imbued vibrancy in things both animal and vegetable, every motion now seen with an emotion.

The poem opens, or declares: “The deer dislike the lavender and heather.” This is followed by “a buck browses/ the youngest of the apple trees.” Later, a crow “plucks lumps of pumpkin from the compost bin.” Everything from a seed: resistant and/or irresistible. Everything that comes to feed: beggars, maybe, but definitely choosy. The specificity of Light’s eye gives the poem its vitality.

GARDEN

Comparatively, the vegetables are more animalistic and the animals more vegetative. We have the defensive mode of the “thrashed sapling”, and a fig doing its prelapsarian job: “swabs bedroom windows with its splashy leaves.” I love this line with all I have. The mistake would be in thinking this poem was a mere lovely observation—it is the bedroom windows that get the fig-leaf treatment. The deer will not eat the lavender. The fig works to promote prudishness. Truth or time-tested, Light knows the whys. Her gift is letting us experience it in an understated way.

Then we have these scrappy poppies, hackles raised: they “bristle and clench”, their colors indecent. Though they are not the focal point of the poem, I would place these poppies in the Poetic Poppies Pantheon, something I just invented, with the two others: H.D.’s Sea Poppies, with their “fire upon leaf”, Plath’s monthly poppies (July, October) with their mouths, skirts, and flames. Light’s are similarly brassy and sassy, stubborn in hue and rooting. They rightfully “hector” those prim and proper roses. O Rose, thou art sick but we don’t care.

“WITH A RASPING HUM, AND A HUM”

Light’s linguistic and sonic patterns are admirable and masterful, the internal rhymes sung and snug. The slightly ominous quality is furthered by the ebb and flow of sibilance—at its peak in the seemingly most innocuous scene. The poem hisses: it is, after all, under pressure. Or is it the steam and draft: cooling, warming, or warning? In the same way you can alter the temperature of air you breathe out by speed and a pursed or open mouth, Light has grouped vowel sounds for maximum effect to make the words do what they say. This poem would make the oral tradition proud; “Downdraft” needs to be read and heard, every word and sound calling and recalling the ones before and after it. It is impossible to recite it without feeling joy.

TRANSITIONS AND MULTIPLICITIES

It is November in the poem but October, and other milder months, can’t seem to accept it. Leftover Halloween stand-bys (crow, pumpkin) are prominent. Everything possesses the fight over flight instinct.

Light’s smart subtlety never fails to amaze me: every utterance is pleasant on the surface but deep and layered underneath. The multiplicity and depth that is so present in the other characters are in the actions of the narrator. “I dry my boots beside the fire. I set/ my tea to steep on the ledge.” An act of heating something cold followed by an act of cooling something hot. Implied: boots lightening, tea darkening. “I survey the possibilities.”

Q: Can I process this in the comfort of being indoors?

A: Sleeping dog, “Warm as toast and snug, / smug as some tweedy squire”

WIND (tin can down the house): “fipple and chiff” “A gust pipes” (as life), “a down-draft/ puffs once” (extinguished).

OMEN: “Crow and pumpkin: yet to come.”

There is unease in the poem’s ease. The wind’s onomatopoeia as preface. What of these Halloween rejects? It brings to mind the pumpkin head, hurled by the Headless Horseman, the superstitions surrounding a bird entering a house. And here the final loom—looming. The poem ends on this just as we get comfortable, if we ever were. Winter and omens up ahead, considerable and hulking.

I think: the determined nature of nature determined to arrive.

Or to quote my favorite doctor Ian Malcolm: “I’m simply saying that life, uh…finds a way.”

Or to quote the skillful spinner herself: “Who’s never been/ the thrashed sapling or brazen bud,/ all thin dignity determined to arrive?”

Perhaps less Arachne and more Clotho, then, in her execution and creation: Light seems one step ahead of the gods, and above reproach.

—Hannah Sanghee Park

Hannah Sanghee Park is currently a fellow at the MacDowell Colony. Her poem, “Bang,” appeared with Carol Light’s “Downdraft” in 32 Poems 10.2.

March 6, 2013

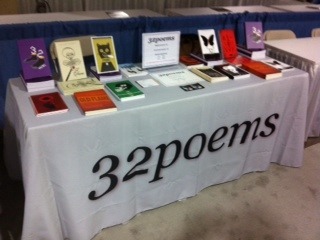

AWP 2013

AWP is underway and we’re in the thick of it.

AWP is underway and we’re in the thick of it.

If you’re in Boston, come say hi and talk poems with us in the book fair (table L20). And don’t forget, tonight at 8pm we’ll be hosting the reading to end all readings at McGreevey’s just down Boylston Street from the convention center. This is the reading you’ll tell your grandchildren about some day, the prom queen of readings, the reading you were meant for. We’ll be celebrating Old Flame and the first ten-years of the journal, but just as importantly we’ll be celebrating the poets who’s work is 32 Poems.

Come hear poems by

Marci Johnson

Terri Witek

Jennifer Militello

Alexandra Teague

Anne Panning

Carrie Jerrell

Melissa Stein

Adam Vines

Holly Karapetkova

Eric Torgersen

Jeffrey Thomson

Kim Bridgford

Bruce Bond

Ken Cormier

Daniel Nester

Carolina Ebeid

March 4, 2013

“Orange as a Bird and Silver as a Nest”

Contributor’s Marginalia: Matthew Thorburn on “Birds of Ohio” by Kathryn Nuernberger

I’m no ornithologist, but birds always catch my eye. At the Bronx Zoo, I gravitate toward the Inca terns and Magellanic penguins in the sea bird aviary. And walking my neighborhood I’ll often stop to watch a bright fillip of blue or red dart from branch to branch before disappearing into the trees. So when my copy of 32 Poems arrived, naturally it was Kathryn Nuernberger’s “Birds of Ohio” I turned to first. Nuernberger’s title made me think of Lorrie Moore’s Birds of America—and like one of Moore’s short stories, this poem soon reveals how ours is an off-kilter and disturbing world.

Structurally, “Birds of Ohio” has the feel of a loosely woven nest: one long stanza with tab-sized gaps here and there where the light shines through. It is, as advertised, a rundown of the state’s birds. And the list form fosters a riffing energy as each bird—“the coal ash chickadee,” “the birds who don’t know / north from south”—is added to this odd flock.

But within this open structure Nuernberger shows her precise way with language, creating both arresting images and lines you need to read aloud to appreciate their sounds. Among these birds, for instance, are “Some / that burrow in the gob and there lay eggs like lost / buckeyes….” Another bird “toe-holds a sunflower / seed and bills it like a jackhammer.” The nouns-as-verbs work perfectly here to make a familiar scene feel strange. That linebreak is sharp too.

Some of Nuernberger’s birds seem normal enough, like the one that “nests the cliff-face of a culvert and trestle bridge” or the one “afraid to cross the shotgunner’s lake.” But then there’s “the bird / that is actually the tiniest copse of trees left / on Starve Island” and “the ones who trip over the tiniest / fiddles of their feet.” I have to admit it took me a couple of reads to realize just what the poem is doing. Birds don’t live only in the air, of course; they land and are part of the landscape. “Birds of Ohio” is about Ohio as much as it’s about birds—or rather, it’s about what living in this post-industrial, rust-belt state has done to the birds.

That “coal ash chickadee” described above is the “little patron saint atop a slate roof in each little city / of the black diamond.” Again Nuernberger’s linebreak, falling between chickadee and little, does its work: what briefly feels like a clever way to say gray-black quickly proves to be literal: one effect of coal mining is coal dust-covered birds. Much of what at first seems metaphorical (at least it did to me) becomes on re-reading a more literal and disturbing take on how the energy industry has hurt the birds of Ohio. “There are birds that cannot land and / cannot perch,” Nuernberger writes, and those birds who lost their north-south sense of direction can no longer migrate. They “stay here and freeze into glass / on the window sill.”

What at first seems an odd poem of vivid, surprising imagery and nifty turns of phrase turns out to also be a sneak-up-on-you-sideways poem of witness. And it’s that much more compelling and fascinating for operating at both levels at once.

“Birds of Ohio” is, finally, a lament. The poem ends not with a bird or even a nest, but with a bleak, wrecked landscape. In the poem’s closing lines, Nuernberger’s artful similes show us what’s no longer there:

…the pitch-squeak backyard rigs pumping their plots

up and down the banks of our collapsed-mine acid creek

which is orange as a bird and silver as a nest.

—Matthew Thorburn

Matthew Thorburn is the author of three books of poems, including This Time Tomorrow (Waywiser Press, 2013) and Every Possible Blue (CW Books, 2012). He lives and works in New York City. For more information, visit www.matthewthorburn.net. His poems, “At Badaling,” and “After the War” appear with Kathryn Nuernberger’s “Birds of Ohio” in 32 Poems 10.2.

Matthew Thorburn is the author of three books of poems, including This Time Tomorrow (Waywiser Press, 2013) and Every Possible Blue (CW Books, 2012). He lives and works in New York City. For more information, visit www.matthewthorburn.net. His poems, “At Badaling,” and “After the War” appear with Kathryn Nuernberger’s “Birds of Ohio” in 32 Poems 10.2.

March 1, 2013

Weekly Prose Feature: Two Lyric Essays by Anna Journey

Isabelle’s Tongue

I just bought the plum-colored, bisque tongue of a broken, antique Kestner baby doll on the internet. I don’t know why, exactly. I’m not a collector. I don’t have tables draped in doilies or cabinets glistening with crystal figurines of cats. I didn’t play with baby dolls as a child. I preferred small, plastic jungle animals. All I know is that as I did research for a poem, scrolling through online listings for bisque head French dolls, I scooted my swivel chair closer to my computer screen to stare at the following listing: “Tongue from a damaged antique large Kestner baby doll, marked with the NO. 16.” The tongue was five dollars. It was plump, an inch long, linked by a mottled black hinge to a little pancake of flesh-colored bisque, the latter of which had once formed the hard palate inside the now-shattered—and vanished—doll’s open mouth. On the smooth underside of the tongue, a factory worker had inscribed the number sixteen. “Am I a freak if I buy an antique doll’s tongue on the internet?” I called out from my office to my husband who typed in the back bedroom—the former sun parlor—of our Craftsman bungalow. David—also a writer—appeared in my doorway to scrutinize the image. He flicked his thumbnail through his beard, nodding. “Oh,” he said, “you have to have it.”

*

I’ve learned that the J.D. Kestner doll company produced dolls for over ninety years, from the early 1820s to approximately 1938, in the Waltershausen, Thuringia, region of Germany. This makes my doll’s tongue at least seventy-four-years-old. I’ve also discovered that, in addition to a mold mark and the phrase, “Made in Germany,” Kestner designers inscribed their dolls with a number that specified the size of the doll. Thus, my doll’s tongue was once hinged to a bisque baby’s head sixteen inches in circumference, the approximate skull-size of a child who’s larger than a newborn but still less than a year old.

*

In five days, my husband will drive ten minutes to a hospital in Santa Monica to have a vasectomy. “I’m never going to have children,” I’ve said for sixteen years, since I was a fifteen-year-old girl. “But if I ever did have a kid—in a parallel universe—I’d name her Isabelle.”

*

Three days until the vasectomy and my tongue hasn’t yet arrived in the mail. A woman who collects doll parts has already shipped the package, from her home in Rushville, Indiana. I learn this information by checking the tracking number courtesy of the USPS. I’ve discovered that some of Rushville’s other notable residents include Wendell Willkie, the dark horse Republican Party nominee who ran against Roosevelt during the 1940 presidential election, and a high school student named Tyell Morton, who was arrested by Rushville police last spring, after he left an inflatable sex doll inside a restroom in his school.

I like to imagine my tongue-sender—whose online username is “katydid22”—lives in a red-brick Victorian with cream trim, on the quiet and iron-fenced Perkins Street, like the picture of the house I found when I searched for images of Rushville, Indiana, on the internet. Her name is probably Katy. She may be twenty-two. She may have inherited the house from her grandmother, who had also collected dolls. Katy may have replaced the rows of porcelain knobs on her two antique walnut nightstands—one on either side of the bed—with small, bisque doll heads, their necks screwed to the right so those pupiled blue irises point toward the doorway. This way, Katy’s guardians keep watch while she sleeps.

*

Her name is Kathy—with a “th”—says the first class mailing label. Kathy J. Williams, from Rushville. I knife open the tiny cardboard box, unwind the tongue from its layer of rose-pink bubble wrap, and sit the mock-muscle on top of my desk. If I press down on the tongue with my fingertip and then let go, the piece flaps back up, like a piano’s sustain pedal. I leave the object on top of my desk for months, unsure about how to display it. Earnest and spare within a bell jar? Ironic in a bright, ceramic dish of butterscotch candies? Arty in a cabinet, sat between a cast-brass hummingbird skull and a holographic set of illustrated folk myths from the Museum of Jurassic Technology?

*

I went through a phase in childhood where I named everything that came into my possession Charlie, no matter the thing’s species or distinguishable sex: the black-and-white female rescue cat with the ripped ear; the Chinese fire belly newt I ultimately freed (irresponsibly) in my neighbors’ creek; the pet rock with the glued-on, wobbly eyes; the stuffed golden lab; the potted aloe. “Have you seen Charlie?” I’d ask my mother, breathlessly, as she suppressed a smile and wiped her hands on a blue dishtowel looped to the fridge. “Which one?”

*

I’ve wondered why I waited so long to use “Isabelle,” why I finally bestowed the name on an impulse buy, a random fragment. Why did I give away my prized name to a partial object, the rest of it crumbled out there—someplace? Even the aloe was whole. Even the pet rock had a face.

*

I don’t remember exactly when I threw the tongue away. I guess I couldn’t settle on a way to display it. The tongue had become part of my desk’s clutter: four different kinds of post-it notes (bird-printed, leaf-stamped, plain yellow, monogrammed with my full name in red); a collaged strata of scrawled poem-ideas, to-do lists, and reminders; stacks of books—Rachel Poliquin’s Taxidermy and the Culture of Longing—which I keep meaning to finish—Beckian Fritz Goldberg’s searing lyrics in Reliquary Fever: New and Selected Poems, a monograph of Francesca Woodman’s disturbing self-portraits of the photographer crawling nude through the slot in a gravestone or lying sideways near a dead eel. I didn’t have room for a tongue that sat here for a year—mute, refusing to speak.

*

Before popping a five-strip of Mad Hatters to trigger an LSD trip, when I was seventeen, I carefully drew an upper lip and pair of cartoon eyes on the side of my right pointer finger, in blue ink, and then sketched a lower lip on the top of my thumb, between its lower and middle knuckles. If I braced my thumb-tip against my pointer’s underside and wiggled my thumb, the drawn-on lips lined up to form a mouth that moved, as if my hand now had a face that could talk. I hoped the face would magically snap to sentience during my acid trip, so I could have wild conversations with it at the Grateful Dead-themed music festival in Brandywine, Maryland, where I was camping with friends for three days. “It’s family friendly, see?” I’d told my mother, showing her the flyer with a picture of musical notes floating above a rainbow over a tent-covered field and the words, “Dogs and children welcome.”

*

“Are you and David going to have children?” my friend Sarah asked me as we walked back from a coffee shop on the Venice boardwalk about a week after I’d eloped. Sarah, a Montana-born third-wave feminist who’d met her partner at a sweat lodge in the desert outside Phoenix, had two kids and the longest hair I’d seen outside the parking lot of a Phish concert. I’ve found that if I answer too quickly in the negative when someone inquires about my reproductive plans, I risk seeming like a fairy tale villain who’d sooner make a child-stew than a child’s bed. “No,” I said simply, after a casual, non-child-hating pause. “I understand completely,” she said, nodding.

*

As the acid began to kick in, my friends and I had positioned ourselves in a clump on a purple batik blanket on the grass next to our four-person tent. “It’s a magic carpet,” my friend John declared in a conspiratorial whisper. The rest of us agreed, and began to sway from side to side, as if the blanket were flying and rippling around Wilmer’s Park, above the heads of people playing didgeridoos or hula hooping before that night’s music acts started up. “Hey,” my friend Erin said, looking at my hand, “is it talking yet?” I stopped swaying and stared down at the face I’d drawn. The blue ink stood out in an icy, nearly vibrating harshness on my pale, freckled fingers. The cartoon mouth had taking on a mocking, sinister pout as if to imply, “Did you really believe I could speak without a tongue?” I spit a long drool-drip of saliva across the lips and eyes and smeared the ink with my other thumb, until the place where the face once was became a fraying, cobalt stain.

*

I’ve begun to wonder if Kathy read the Rushville paper the day Tyell Morton’s arrest was announced, if she found his propping an inflatable sex doll in one of his high school’s restrooms offensive or worthy of an arrest. “Now they’re arresting people for making statements with dolls?” she might wonder. Maybe she isn’t as conventional as her Indiana grandmother, Mabel. Maybe, late one night, she drove to the police precinct and left a pile of bisque babies’ bottoms on the front step, their anatomically incorrect, anus-less buttocks tipped up toward the Midwestern dusk. Wouldn’t a woman who sells old doll parts for a living have to have a sense of humor? Or maybe she’s despairing, rage-filled. Maybe she couldn’t conceive all those nights trying between the cornfields and so sells smashed-up dolls to strangers. Maybe they wouldn’t speak back to her either and she no longer wanted to wait.

*

Rushville’s Wendell Willkie—the dark horse Republican Party nominee in 1940. I like the term “dark horse.” It seems too poetic for use in political jargon. It comes from horseracing, actually. It means “a little-known person or thing who emerges to prominence.” Dark horse doll-lady Kathy. Dark horse prankster Tyell. Dark horse sex doll swelled to human-size in the high school restroom. Dark horse absurd arrest. Dark horse Wendell dead just four years after running for president. Dark horse heart attack at the end of his phantom first term. Dark horse sperm cinched off in the infamous operation. Dark horse tongue I named and threw away. Dark horse Isabelle. Dark horse face. A whole dark horse year, another, as they race.

Notes for a Fugitive

My cousin Kenneth can’t slip from the safe soil of Mexico and step into Texas without getting arrested. Redneck turned English teacher. Acne I could see from a satellite. High-school-educated, haphazard pot farmer and (former?) racist. Slur-hurler now married to a woman with a brown face—a Mexican doctor. Two biracial kids and a stucco place. Kenneth fled his mother Beulah’s doublewide in Greenwood, Mississippi—and his arrest warrant—after he shot off a guy’s kneecap at a dive bar. Some argument over a girl. I haven’t seen or spoken to Kenneth in over twenty years. The last and only full memory I have of him is this: It’s 1990. I’m ten-years-old. My little sister Rebecca’s seven. Kenneth’s eighteen. He’s leading us through the buzzing kudzu to a dry creek bed behind our Papaw’s hand-built two-story. The rusted cherry-picker overgrown as a Mesozoic ginkgo. Snare of blackberries in our red hair. Where are we going where even the water got up and fled town? Where the cicadas wrest themselves up from themselves, leaving their old halves behind—faux golden and glued down?

Kenneth walks ahead of us in this sliver of memory so thin I could slide it under my tongue. The pin oaks’ wiry roots, once submerged, now crosshatch the dry creek like whitened crawdad cages. We walk in silence, until we find an empty shell of a tortoise lying on the cracked, apricot dirt. Rebecca and I are afraid to touch it, but Kenneth picks it up, turns it over. There’s a backbone in low relief that rises from the inside of the shell—the dirt dusted between the vertebrae. In just months my mother will plunge through our attic floor and shatter her back. But I don’t know that yet—in this space—the heat swaying from the humidity that claims its own partially visible weight. We take the shell with us and I begin to pick at its layer of taffy-and-olive-flecked-brown to reveal the bare patchwork of bone beneath.

The picked-clean carapace is more skeleton than shell, is a boat for my Barbies, is a musty relic, is a lost piece of my Mississippi visits. But who is Kenneth? Who was he and who is he now? Who changed the channel when Rebecca and I watched shows with black faces on TV, as we happily rapped along to the theme song of “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air”? Who had oily, dishwater hair we called, in whispers, “Captain Mullet”? Who used words that made my mother say in a low tone of fury, “Never around my children”? Who had a lattice of spades and pitchforks thrusting up in the front yard instead of asters? Who called the four pit bulls and three obese cats “Little Girl” instead of granting each one a name?

My father’s middle name is Kenneth. He was supposed to be called “Ken,” for short, except my aunt Beulah, as a child, couldn’t say the “k.” Instead of “Ken,” she said, “Tim,” which became his name: “Kenneth” vanishing like my cousin vanished after blasting off that man’s kneecap with a Smith & Wesson. When the kneecap popped off, did it resemble the tortoise shell, spinning across the dive’s tiled floor? More likely, it shattered like my mother’s spine, like the rules of grammar long fractured in my cousin’s mouth. I don’t know how a man who couldn’t speak a single sentence without sounding like a backwoods Mississippi hillbilly could now teach English classes in Mexico. Apparently, though, a woman savvy enough to complete medical school must have seen something redeeming in him. Has he replaced “spic” with “cinnamon-skinned pediatrician,” “wetback” with “the curves of her spine”? Why did he become a teacher in the field of English—my field—which he filtered through his ignorance and maligned? How can I judge someone I no longer know—never really did know as a kid, following a future fugitive down the skeletal street of an evaporated creek? As I held out my hands to receive the tortoise shell, I saw it was empty and wondered how the living meat had freed itself—for good—of the Greenwood dirt.

—Anna Journey

Anna Journey is the author of the poetry collections Vulgar Remedies (Louisiana State University Press, 2013) and If Birds Gather Your Hair for Nesting (University of Georgia Press, 2009), which was selected by Thomas Lux for the National Poetry Series. Her poems have appeared in American Poetry Review, The Best American Poetry, FIELD, The Kenyon Review, The Southern Review, and elsewhere. She’s received fellowships for poetry from Yaddo and the National Endowment for the Arts, and she teaches creative writing in Pacific University’s Master of Fine Arts in Writing program.

Anna Journey is the author of the poetry collections Vulgar Remedies (Louisiana State University Press, 2013) and If Birds Gather Your Hair for Nesting (University of Georgia Press, 2009), which was selected by Thomas Lux for the National Poetry Series. Her poems have appeared in American Poetry Review, The Best American Poetry, FIELD, The Kenyon Review, The Southern Review, and elsewhere. She’s received fellowships for poetry from Yaddo and the National Endowment for the Arts, and she teaches creative writing in Pacific University’s Master of Fine Arts in Writing program.

Each Friday we will publish a new essay, review, or interview for the 32 Poems Weekly Prose Feature, edited by Emilia Phillips. If you have any questions or comments about the series, please contact Emilia at emiliaphillips@32poems.com. Note: The Weekly Prose Feature will go on hiatus for the AWP Conference in Boston, Massachusetts. We will resume the feature on Friday, March 15th. Be here the Ides of March!

February 27, 2013

The Next Big Thing Interview: Malachi Black

In the last week, I’ve been very happy to be “tagged” in a rolling self-interview series called “The Next Big Thing” by two unrelated but equally estimable poets: Kent Shaw and Luke Hankins. As a recent 32 Poems contributor, it’s my pleasure both to participate in the series here and to “tag” four other 32 Poems poets for next week.

QUESTIONS:

1. What is the working title of the book?

Storm Toward Morning.

2. Where did the idea come from for the book?

I’m still fiddling with the contents, but the poems in the present iteration of the manuscript were written (and rewritten) over the span of approximately eight years. Thus I feel somewhat uneasy in assigning one central idea to the book, although I’ll say that the poems (if those may be considered “ideas”) emerged from the same fundamental sense of precarious strangeness. Each of the poems in its own way contends with the burden of being, or, more precisely, of being in possession of faculties whose reflex is to make sense of themselves and their surroundings—surely that is one definition of consciousness—on the only planet known to sponsor any form of sentience. And in a vast, expanding universe, I might add, that seems essentially unconcerned with us.

3. What genre does your book fall under?

Poetry (lyric).

4. What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition?

Yikes, I don’t know. Paul Dano? And certainly my dear friend , to whom I send a continuous stream of hearty, heartfelt congratulations for his role in the Oscar-winning Argo.

5. What is the one sentence synopsis of your book?

There is nothing more truly peculiar, confusing, and surprising than being entirely alive.

6. How long did it take you to write the first draft of the manuscript?

I’m still working on it! But the very first draft took me roughly six years.

7. Who or what inspired you to write this book?

Eek! In typical verbose fashion, I seem to have answered this already.

8. What else about your book might pique the reader’s interest?

That several of the poems first appeared in 32 Poems! Also, that much of the work is invested in making “old” forms “new.”

9. Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency?

It will be published by Copper Canyon Press next year (2014).

10. My tagged writers for next Wednesday are:

In alphabetical order:

Rebecca Gayle Howell

Rebecca Lindenberg

Jessica Piazza

Caki Wilkinson

↔

Malachi Black is the author of Storm Toward Morning, forthcoming from Copper Canyon Press, and two limited edition chapbooks: Quarantine (Argos Books, 2012) and Echolocation (Float Press, 2010). His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Poetry, Boston Review, Narrative, The Iowa Review, Harvard Review, and Verse Daily, among other journals, and in several recent and forthcoming anthologies, including The Yale Anthology of the Devotional Lyric, Poems of Devotion: An Anthology of Recent Poets, and Discoveries: New Writing from The Iowa Review. The recipient of a 2009 Ruth Lilly Fellowship, Black has also received recent fellowships and awards from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, The MacDowell Colony, the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and the University of Texas at Austin’s Michener Center for Writers, where he earned his MFA. A current Vice Presidential Fellow at the University of Utah, he was the subject of an Emerging Poet profile by Mark Jarman in the Fall 2011 issue of the Academy of American Poets’ American Poet magazine.

February 25, 2013

Talk it Up

Contributor’s Marginalia: Noah Kucij on “Outfielder” by Matt Sumpter

Poets. You can’t take us anywhere. Whether we’re in the waiting room, in a station of the metro or a supermarket in California, we’re always doing more than just waiting, commuting or shopping. We’re poking at the melons of every experience, transforming the faces around us into fresh images, discovering that we exist and/or that we will one day cease to. It’s no fun for anyone else, and while we are allowed to have jobs and families and ovens, we’re rarely put in charge of the department or entrusted with cooking a turkey. “Outsider” is a bit overwrought for what we are. “Outfielder” is closer to right. Matt Sumpter has given us both a very good baseball poem and a mascot for our motley team.

I like how Sumpter establishes his speaker as half-in/half-out, a participant on the margins. Being in the outfield helps – it’s arguably the loneliest, the most removed position in team sports. The admission that “I barely made the team” is further fodder. And then there’s the poem’s fixation on baseball’s marginalia. Even to its practitioners, the game is as much about unwritten rules and unathletic customs as it is about balls and strikes. There’s a waiting well of poeticisms that never seem to get old; even the most tongue-tied and literal among us can speak with ease of a frozen rope, some chin music or a runner in a pickle. Sumpter eschews these easy morsels, but vividly evokes the trappings just beyond the diamond nevertheless: “hard-case chatter” and “dip” in the dugout, women “like cinders” in the stands. The trivial and the essential are all mixed up. Baseball imitates life once again.

And then, into this nicely drawn scene, emerges a bit of novelty: a crow that has met its end in the batting-cage netting. The speaker jumps at the chance to “put it down” because it gives him a role, albeit an eccentric one. Plus, dead animals are truffles for poets. We can’t keep our noses out of them. It’s while the speaker presides over this death that the poem reaches new lyrical altitudes. We get this:

His wingtips reached

for the shadows they were made from.

At dusk, the ball will disappear that way,

becoming movement, sound, as we cut

our names in dirt with metal cleats,

believing fields of onion grass are endless.

How familiar, this swath of revelry and revelation that extends from a single literal moment outward into space. How much like so many of my own very pleasant, public space-outs. Sumpter shows his speaker doing very poet-y things, transforming an everyday encounter which “no one talks / about” into measured doses of incantation and dreaminess. Making the whole scene and moment – summer night, amateur baseball, dead bird – into everything it can be with the help of a little magical thinking.

Then, in counterpoint to all this lush lyricism, the poem ends with a sobering line-drive: “A teammate called: / It is what it is. Forget that shit.” I like the poem most of all for this final balancing act, in which its very poetry-ness meets the blunt prose of the dugout. Those of us who get off on complexity and transformative thinking should hate that ubiquitous phrase, It is what it is, but somehow it often seems just the ticket, just the saltine for the queasiness of life. Here, I don’t think we’re meant to swallow it whole – the poet is meant to keep playing shaman and eulogist as well as right fielder – but it is a nice reminder to look alive out there, that the count is full and the runners will be going.

—Noah Kucij

Noah Kucij’s poems and essays have appeared in Cortland Review, Slow Trains, LOST, and in two collections from Toadlily Press. He teaches at Hudson Valley Community College in Troy, NY. His poem, “The Belt,” appears with Matt Sumpter’s “Outfielder” in 32 Poems 10.2.

February 22, 2013

Weekly Prose Feature: “An Interview with Sebastian Matthews” by Justin Bigos

Sebastian Matthews is the author of a memoir and two books of poems, most recently Miracle Day (Red Hen Press, 2012). He teaches undergraduate creative writing at Warren Wilson College and serves on the faculty of the Low-Residency MFA at Queens University, Charlotte. He is working on a novel. 32 Poems previously published an interview with Sebastian Matthews by Serena Agusto-Cox in December 2010; to read that interview, click here.

Sebastian Matthews is the author of a memoir and two books of poems, most recently Miracle Day (Red Hen Press, 2012). He teaches undergraduate creative writing at Warren Wilson College and serves on the faculty of the Low-Residency MFA at Queens University, Charlotte. He is working on a novel. 32 Poems previously published an interview with Sebastian Matthews by Serena Agusto-Cox in December 2010; to read that interview, click here.

Justin Bigos: Your latest book of poems, Miracle Day, has much to admire, but I suppose what I admire most is the generosity, the almost self-effacement, of the speaker. For example, in the poem “Hearing Ilya Read for the First Time,” we not only hear the speaker’s entrancement by the poet Ilya Kaminsky, but also the crowd’s—and then we are given the surprising final image of a fiction writer who with great bravery must step to the podium and read after the show-stopping performance of Kaminsky. In another poem, dedicated to you father, the poet William Matthews, on the tenth anniversary of his death, your speaker seems to step completely out of the scene at the end, giving the poem, in a sense, to your father and his father, visions or maybe ghosts, studying a wine menu at a bistro. So while your speakers are very present in the music of their language and force of observation, they are sometimes absorbed into what they witness and love. I think the dual quality I’m trying to describe is captured in the last line of your poem “Zones of Providence”: a speaker who is “besotted admirer and blurred subject both.” Okay, now I’ll step away and let you talk. Tell us about these “mid-life songs” of Miracle Day.

Sebastian Matthews: Well, first off, I want to thank you for inviting me to talk about my poems, and about this book. It’s an honor. And just a little strange because I have been so removed from the book ever since it came out. I might even say estranged, for my family was in a huge car accident, a head-on collision, and it has taken now a year and a half to make our recovery. It’s been hard, as one might imagine, and more than a little time- (and energy-) consuming. I had to drop a lot of things just to make it through. In fact, I am still in the process of dropping things, so much so it feels at times like I have very little left to hold onto. And I guess the poems were one of the first things to drop. It was easy—the whole book, really—for I’d written the poems and so they were out there already in the world in some small way. Maybe too easy, for now I have almost forgotten them. So it’s a treat, and a surprise, to be asked to return to them, if only to say a few things about their conception.

I like your ideas about stepping out of the poem at the end. I’d never thought of it quite like that before, but that might be my ideal ending for a poem—getting it so right in voice and scene and music that the voice behind the thing can disappear, step off stage, and the whole thing might keep moving for a while on its own. It’s a little like when a narrator in a novel was just a second ago talking to you but all of a sudden is nowhere to be found. The reader is left in the scene unfolding at his feet.

Before the accident, I used to dream often of driving a car on a highway—one of those small curvy ones on the west coast—and in the dream I’d get to the point where I lost track of the car and was steering from somewhere behind—the dream had split one car and driver into a pair—so now I was unable to see where the car was actually going; and I’d have to steer blind, so to speak, guessing where the car would bank for the turn or when it would pass another car. I don’t have that dream anymore. But it was always an exhilarating and anxious feeling, a kind of fuck-it-I’ll-play-it-by-feel experience that I think writing poems can be like at times. Why not simply let go—a parent behind his child letting go of the bike—and see where the small craft ends up?

As for “mid-life” songs, that phrase first became attached to many of these poems as a kind of joke or self-criticism. I was writing too many of the same kind of poor-me-I’m-getting-older poems. They were too tame and self-involved. As an antidote, I started writing what I called “braggin’ pomes,” which were shorter, more emotional poems, with an often pissed-off or hyped-up narrator—poems about playing basketball or creating music. But also poems responding to perceived slights, possibly paranoid and most certainly with hackles up. There are obvious potential pitfalls in this kind of poem, as well, but it felt worse if I didn’t attempt them. Garrett Hongo, an early supporter of my work, had told me it was time to write about different subjects; and I remember reading Tony Hoagland about tone and how he feels poets nowadays are afraid of being a little mean. There are both types of poems in the book—introspective and brash—but only the “mid-life songs” subtitle stuck.

JB: I like the connection you make between your dream and the writing of poems, and I do feel that in many of your poems you are doing just what you describe, kind of “going on your nerve,” to quote O’Hara. Many of your poems seem to thrive on the unpredictability of consciousness and feeling, the paths they take, the paths they veer from. For example, your prose poem “Ars Poetica Blues” takes a sharp, surreal turn at the end; the last line reads: “And the bottles on the table rattle as the milk truck tanks roll by.” To my ear, the key moment before that image, the hinge, is the statement, “And no one cares.” At that point, the poem seems free to find its own way, regardless of who’s listening. Do you feel similar moments in other poems you’ve written?

SM: Well, “Detour Ahead” worked a lot that way. I knew I wanted to write about the drive I took from a conference in North Carolina into New England and through Pennsylvania. I had taken a misguided detour through Philly that plopped me down into a whole new place—both geographically and emotionally. Like the drive, I knew I wanted in writing the poem to explore this realm (to talk about how the detour altered things) but wasn’t sure what I’d do when I got there. So when I got to the point in the story where I was driving in circles around downtown Philly, lost and trying to find a way back out, I was also lost and circling in the poem. I had written that I’d been listening to Bill Evans, which is true, I was listening to Evans throughout the detour drive, but I’d forgotten about it until I remembered, sitting there at the desk, the whole Scott LaFaro story—his dying tragically young in a car crash—and that began to focus me again. So as I drove on up through the city, and through the poem, I had a new rhythm and pulse that had become attuned to the Evans tune and its steady rhythm. And, in that way, the whole last part came to me out of the blue. I had the song on as I was writing the poem, and in my head I was back in the car, and the whole thing was, as you say, “free to find its own way.”

Like many poets of my generation, I guess I am an adherent to Hugo’s whole “triggering town” idea. That you don’t have to end up where you started.

JB: It’s interesting that you see the influence of Hugo as generational. I think I’m only about ten years younger than you, but when I finally got around to reading Hugo’s Triggering Town, I both felt exhilarated by it, and also that I had somehow already read it—maybe because it’s now “in the water,” so to speak. Can you talk more about Hugo, and his influence on your poetic “triggers”?

SM: Yeah, I might be wrong about the generation thing. The book’s definitely in the water though. Just today, in an Intro to Creative Writing class, I had a student apologize for “wandering off topic.” He said, “I tried to stay on topic but I kept drifting.” And, of course, for me drifting is what it’s about—the little improvisation inside the song’s structure.

Hugo was a big influence all around for me. His poems, The Triggering Town, the “autobiography in essays” that came out after his death. (He even wrote a great—and strange—detective novel.) He just seemed so sad and so earnest yet so in love with the world, especially the small and unnoticed and underappreciated things. Along with James Wright and, to some degree, Robert Bly and William Stafford, Hugo made clear to me how important it was to pay attention to the everyday—to see beauty in it, to get at the dark parts—and to raise it up for inspection.

Hugo has always reminded me of Rilke but reincarnated as a circus bear or a minor league baseball clown. I got to meet him a few times, first when I was a kid and he came to Boulder, Colorado, to teach. He was there the day I got attacked by a dog while riding my bike up on an old mountain road. He was a very warm-hearted guy, attentive to kids. He loved baseball and ice cream and dogs (though not the beast that bit me). What was not to like? And I spent a little time with him in Seattle just before he died. He and my father were friends; I was in high school and so joined my dad on his visits to the hospital. It just killed me to see Hugo that sick and my father that bereft.

JB: Miracle Day is divided into three sections, “Early,” “Middle,” and “Late,” and preceding each section is a kind of introductory or interstitial poem that is set in a different font than the rest of the book. These poems seem to add an extra layer of authorial presence over the pages. Can you talk a bit about your choice to include these poems as both separate and integral to the collection?

SM: I have seen other books that do this and always liked it. Though it’s a little different, my father’s A Happy Childhood used those Freud poems as load-bearing posts. I wanted the three longer poems in Miracle Day to do some of that work—and it felt right somehow to place them at the front of each section. It was Red Hen Press’s idea to put those three poems in a different font. I was reluctant to do it at first but have since grown to enjoy the affect.

With the whole “Early,” “Middle,” and “Late” thing, I wanted to play with the idea of mid-life as this zone one moved through in stages. I finished the book just before I turned 45, so I was jumping the gun a little. But once I laid the thing out that way, poems began migrating to their appropriate zones. And it made a kind of emotional sense to start with the cell phone poem and end with the driving poem, which put the black ice poem center. It’s the way I’ve come to put together collections of poems, it seems. Is there a manual for how one goes about the process? Hopefully not—but I bet there have been AWP panels about the idea. The kind of panel I usually avoid.

JB: Earlier you mentioned the car accident you and your family were in a year and a half ago. I confess that when I read your poem “Left-Handed,” I initially thought it was about this accident, but at some point I realized—mainly because your wife is absent from the poem, and the injuries are not as severe—that it must have been a different accident. And the road as an image of peril pops up in other poems in the collection. Your neck of the woods is Asheville, North Carolina, a place near and dear to my own heart, and last summer, on the way from Texas to Asheville, my wife and I were also in a major car wreck—and, except for a couplet, I have not been able to write about it. Can you talk a bit about writing from—or maybe through—trauma?

SM: As you know, a serious car accident turns your life around. It’s one helluva big-time scary wake-up call. The accident I wrote about in “Left-Handed” was certainly scary—a little something black ice can do—but my son and I escaped from that mishap with only minor injuries and frayed nerves. The recent crash (and hopefully our last) really created some damage. My wife and I were first confined to our beds then to wheelchairs for the first bunch of months. Luckily, our boy was unhurt. But, still, everything in our life changed; and even now, a year and a half later, we are still coping with the long-term effects of the crash, emotionally and physically.

I was pretty sure I wasn’t going to write about the crash, at least not for some time. I had jotted down a few small poems, a handful of lines, while in the hospital, but pretty quickly all my energy got sucked into rehabbing, caring for my family as they cared for me. But about six or seven months into the recovery something burst inside and I felt a powerful desire to purge myself—my body, my brain, my heart—of the feelings and memories that had welled up. I had become haunted by the experience—in particular, by the fact that the man who ran into us head-on did so because of a fatal heart attack. Something about his bad luck running into ours—of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. And because we were on our way up the mountain to celebrate “family day” with our son who had entered our lives exactly eight years before. That some force had plowed in and upended our happiness.

What allowed me to respond to this catastrophe at all was the idea of writing a little every day for a month, which was the main concept of The Grind, an internet experiment in writing that Ross White and Matthew Olzmann have created. You join a group of like-minded writers—poets, prosers, hybrid writers—and together witness each other’s journey through a month of writing. It doesn’t matter if you only write five minutes each morning, you still have a built-in audience of writers attempting the same thing. So about 10 months out, in June 2012, I wrote a series of poems, one a day for a month, that I now call the “Dear Virgo” poems. For some reason, I began writing faux-horoscopes to myself in a mocking, bitter voice. Something about the mean-spirited and angry voice felt appropriate. And though I wasn’t writing directly about the accident, it felt like I was at least releasing some of the raw emotions surrounding the event.

I tried again in August of the same year, this time with the plan of writing “head-on” about the accident—to meet force with force. And so I sat down and started writing poems about specific aspects of the accident—the crash itself, the first five minutes after when we weren’t sure how bad things were, the hour I spent trapped in the car, the first days of ICU, etc. One of my last poems was a letter to the man’s son. And, as with the first “Dear Virgo” attempts, I made a photomontage image for each poem so that, by the end of that second month, I had created 60 poem-collage pairs; and by then I had literally written myself through the experience. I was totally spent and felt like I’d never write another poem ever again. But it was worth it, for I felt more myself and more present in my life. Less haunted. Ready to try something new.

As for “writing through trauma,” I think that’s a good way to phrase it. Writing about trauma can only take you so far; you begin to move past your subject only when you break your gaze from it. You start out writing about trauma but before too long you’re in the throes of despair and writing about a chair. As Charles Baxter so sagely put it: “People in a traumatized state tend to love their furniture.”

JB: It’s clear from your poems that you love music, in particular blues and jazz. In the poem “The Living Room Sessions,” the speaker listens for the first time to Lonnie Johnson: “the voice is Billie Holiday/ grafted onto a bottleneck guitar, dragged/ down a long dirt road.” In another poem the speaker delights in an Eddie Locke drum solo, as Locke’s virtuosity and showmanship moves “way past decorum.” Can you talk about this ekphrastic impulse in your work?

SM: Would love to. It’s one of my favorite things to do, writing off the trigger of music, or art, or film. I don’t think the work I produce in this vein is often very good—though I get a few good ones here and there—but it’s the act itself that counts. It’s a kind of practice for me, a way to warm up—for I know I can always listen or look carefully and respond on the page. Al Young used to have our workshop group listen to music and write off or out of the song. I remember picking an epic Mingus song and writing page after page. Which reminds me of one of Al’s criticisms of my work. He said, “You sure write pretty, but what’s it about?”

And, if I think about it a little, the poems that do work, as I think the two you mention above do, it’s because there’s an intensity attached to the listening act. It’s not just art for art’s sake but also an experience I am trying to get at—an analogous soul. The Locke drum solo poem came to me in a fit of frustration and humor. I had been trying to write something with the album on in the background and as the solo kept going and going—I’d not heard the song before done this way, live—I had to put down my project and simply marvel at the audacity of the musician taking up this much space inside a performance. It’s as if he were saying, “Shit, if Trane can go on for half an hour, why can’t I?”

In Geoff Dyer’s book on jazz, But Beautiful, which ranks as one of the best books on the subject)he paraphrases George Steiner by saying that all real criticism in art is simply one artist responding to another. I love the idea that art is often spurred on by other art, and that the artist, the poet, has to look back as well as look forward when creating new material. Not so much the anxiety of influence as the joy of call and response. Anything you can do, I can do better.

JB: Returning a bit to the subject of western Carolina, can you tell us a bit about Black Mountain College, another subject of some of your poems? I’m particularly interested in your personal connection to its legacy.

SM: Well, more than anything, I am a big fan of Black Mountain College and its legacy as an experimental, “arts-based” college. I look to it as a model—an ideal, really—for my own teaching and the work I do with the undergraduates at Warren Wilson College. I love the way Albers and Co. exploded the traditional classroom and in doing so let in so many other forms of learning.

I spent a few years first on the board of and then working for The Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, which allowed me to learn more about the storied history of the place while getting more deeply involved with the Asheville area arts scene. During that time, I worked with the director of BMCM+AC, Alice Sebrell, curating a show of Ray Johnson’s early collage work. I had a great, good time working on that and learned a ton in the process.

As for the legacy of the “Black Mountain” school of poets, I must say that I am only passingly influenced by that avant-garde thread of American poetics—as embodied by Olson, Creeley, Duncan, Levertov, and others. Creeley has always been my favorite of the bunch, though, and I have become a huge fan of Jonathan Williams’s work, as poet, editor, and photographer. Over the years, I have gained more and more respect for the work of poet and teacher M.C. Richards.

Part of my interest in BMC comes from my belief that all art is, at its root, place-based and time-bound. We write out of a particular time and place, one of a chorus of voices working together to do some good in the world—by witnessing it and singing its truths. When I moved to Asheville in 1999, it made sense to learn more about the Southern Appalachian literary scene—both in the past and in the present—and also about Black Mountain. I have only scratched the surface, of course. But it’s where the impulse for the literary journal Rivendell came from—and why along with co-editor Ryan Walsh I spent a year gathering work for the Southern Appalachia: Native Genius issue. Paying my dues, you might say.

JB: Aside from Miracle Day’s dedication (“to my friends”), the book itself has more than a few poems dedicated to friends. And I notice that the dedications, unlike the current trend in poetry collections, are not in the “Notes” at the end of the book, but right there next to the poems. On the other hand, the dedications are not epigraphs, but instead appended to the ends of the poems. Off the top of my head, the only other poet I can think of who does this is Stephen Dobyns, but maybe there are more. Is there a reason you dedicate your poems in this particular way?

SM: I think this idea of being time-bound and place-based plays into this tendency, as well. I write primarily for, or in the light of, my friends and their own work. And though we may not live in the same place, they are my first and most important community of readers. I think this is true for most writers—our friends become the ground under our feet. That sounds a little weird but hopefully I’m making sense here . . .

I put the dedications at the ends of poems because I wanted the reader to see the connection directly—even if they don’t know the person for whom I am dedicating the poem. It’s not so much an after-thought or a note at the back of the book, which feels a bit academic and formal. More like a letter, in the vein of Hugo’s letter-to-friends poems. Tips of the hat. But I didn’t want to put them at the top because that reference might color or overpower the poem itself. It felt right at the time, though I don’t think I’ll do it that way again.

JB: Let’s end our conversation with fatherhood, a theme that runs throughout Miracle Day. In the title poem, you write: “One of the gifts of fatherhood,/ my brother once told me, is to be summoned/ from the dingy corridors of your inner life.” Can you tell us how fatherhood has changed you as a poet?

SM: Well, it’s made me a better man. Which can help, though not always, with writing poems. But you’re talking about change as a poet. That’s a cool question. Off the cuff, I’d say being a dad has made me write about different things—or to see the same old things from a different vantage. I am not sure I have written any great poems about being a father, though I think the “East Village Grille” poem is the closest I’ve gotten. There’s such a risk of sentimentality when writing about one’s son, the love for a son, what it means to be a dad, etc. It’s an easy rut to fall into and a hard one to climb out of.

But I guess the reason I love that remark from my brother (I think I added the corridor metaphor) is that it’s really quite obvious but remains startling in its truth. You can’t be as self-centered as you want to be—and poets require lots of time and space to daydream—when you have to work on getting your kid off to school, helping with homework, witnessing soccer matches, and talking your boy down from running away. And, in the case of Avery claiming his right to change families, my wife and I have to jump fast and furious into our boy’s frame of mind in order to avoid patronizing him. Not a good time to raise a rhetorical question or offer a simple bribe.

Traci Brimhall*: Has the process of writing different books felt like serial monogamy? Do poets change their writing practice over time, writing in coffee shops one year and in a converted chicken coop the next? Have their obsessions narrowed in or broadened? Spill the beans, poets!

SM: In many ways my obsessions are always expanding out. For the last set of years I’ve been content with following the whim of my interests wherever they take me. Something like following a butterfly for an hour and calling that my walk for the day. Never the same butterfly, never the same exact excursion.

But even that type of practice (if you can call such play practice) begins to become routine. What started as an expansion morphs into a contraction. I keep taking these “butterfly” walks. The change comes when I go looking for new places to walk—for new starting points. Or when I jump in a car or jump out of a plane or decide the kitchen table is my platform and dive off it.

32 Poems: Now, Sebastian, provide us with a question for our next interview.

SM: I’m curious when and how much you think about the point of view of the poem you’re working on. Do you say, “I’m going to try a second person address for this poem,” or do you find yourself switching from “I” to “you” halfway through the composition process?

Justin Bigos is a doctoral student in English at the University of North Texas, where he serves as Interviews Editor for the American Literary Review. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in magazines including Ploughshares, New England Review, Indiana Review, The Gettysburg Review, and The Collagist. With Kyle McCord, he co-directs the Kraken Reading Series, based in Denton, Texas.

Justin Bigos is a doctoral student in English at the University of North Texas, where he serves as Interviews Editor for the American Literary Review. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in magazines including Ploughshares, New England Review, Indiana Review, The Gettysburg Review, and The Collagist. With Kyle McCord, he co-directs the Kraken Reading Series, based in Denton, Texas.

*As a part of our interview series, we ask each interviewee to provide us with a question for the next interview. On February 15th, we published an interview with Traci Brimhall.

Each Friday we will publish a new essay, review, or interview for the 32 Poems Weekly Prose Feature, edited by Emilia Phillips. If you have any questions or comments about the series, please contact Emilia at emiliaphillips@32poems.com.

February 18, 2013

Wild Civility

Contributor’s Marginalia: Matthew Buckley Smith on “Campus and Dinkytown” by Maryann Corbett

Every time I read a poem, I read it with two minds. By this I don’t mean I’m undecided. Instead, the more I like a poem, the more distinct the minds with which I read it. I like Maryann Corbett’s “Campus and Dinkytown” quite a lot. It’s a smart sonnet about visiting one’s alma mater many years later. When I read it, my two minds clatter away like teenagers texting their boyfriends in study hall. The first one flinches with nostalgia, and the second envies the way Corbett’s verse, while purposeful, flirts with accident.

Most poets have a few rules of thumb they use when writing poems. Some are personal (an allergy to pet stories, say, or a fondness for falling meters). Some are shared (we’re all a bit tired of poems about the way light leaves a dying star, and we’d all like another good rhyme for ‘self’). Many poets I know or admire––sometimes both––seem to have a lot of guidelines in common. In “Campus and Dinkytown,” I recognize some of my own favorite sleights of hand.

These deal with the appearance of intention in the poem. Or more precisely the illusion of its absence. Yeats was paraphrasing every poet ever born when he wrote, “A line will take us hours maybe; / Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought, / Our stitching and unstitching has been naught.” It’s hard to say memorable things in rhyme and meter. It’s even harder to make it look easy. I’ve tried to frame as maxims some of the ways that Corbett’s poem gets all this done. Here goes, in no special order:

1. Rhyme words that have little else in common.

2. Use substitutions and caesurae to avoid boring the ear, but don’t use so many as to cripple the meter.

3. With enjambment, create a satisfying disparity between line and sentence (avoid the near-miss). Also, as in prose, vary sentence length.

4. When a sonic device (alliteration, assonance, internal rhyme) appears in any single line, two of a kind are snappy, three may be eerie, four are idiotic.

5. A syntactical device (anaphora, chiasmus, zeugma) starts losing power the moment it draws attention to itself, which is typically just before you tire of using it.

6. Don’t strive to align small grammatical units (word and sentence) with small metrical units (foot and line). Do strive to align large grammatical units (example and argument) with large metrical units (stanza and poem––obviously).

7. Perfect logic is just as dreary as perfect nonsense. Every poem needs a curve, but most poems need only a small one.

8. When a poem is shackled by images, loosen it with abstraction. When it drifts too far into the abstract, tie it down with imagery.

9. A little doubt saves a poem from stiffening into dogma, a little certainty saves it from lapsing into drivel.

10. If a poem doesn’t strike at the heart on the first reading, all the footnotes in the world won’t finish the job. It might take more than one reading to appreciate a poem fully, but it shouldn’t take more than one to appreciate it at all.

In the first draft of this essay, I composed a sort of key linking each rule to a line (or lines) in “Campus and Dinkytown,” but I think the poem will be better served if you scour it yourself. These guidelines, after all, are only napkin sketches of the poem’s virtues. As is true of all good poems, “Campus and Dinkytown” does not follow rules so much as suggest them.

Besides, this sonnet has other pleasures to offer both minds. One being the way it evokes an older form––the priamel (not this, nor this, instead this)––when it replaces the ninth line’s customary ‘But’ or ‘Yet’ with the gentler “Only.” By fulfilling the grammatical expectation without actually offering a volta, Corbett is able to keep us waiting for some solace until the last, aching sentence: “That truth remains.”

“Campus and Dinkytown” is a drab title that bathrobes a real eyeful. Go have a look.

—Matthew Buckley Smith

Matthew Buckley Smith’s first book is Dirge for an Imaginary World. He lives in Baltimore with his wife, Joanna Pearson. His poems, plays, and reviews appear in public from time to time. His poem, “Voyeurs,” appears with Maryann Corbett’s “Campus and Dinkyton” in 32 Poems 10.2.

February 15, 2013

Weekly Prose Feature: “Biomythography: An Interview with Traci Brimhall” by Emilia Phillips

Emilia Phillips: Tell us a little bit about your arrival into poetry. When did you write your first poem? When did you start thinking about seriously writing poetry? Was there a specific moment in which you said, “Yes, I want to do this”?

Traci Brimhall: I can’t remember a first poem. As long as I’ve written, I’ve written poems. In high school, I definitely wrote lots of poems about my feelings that rhymed, and I took creative writing workshops in college and wrote poems about relationships that didn’t rhyme. But the moment when I said “Yes! This! This is everything!” was a few years after graduating college. I settled down in a good job in the arts, had a house, a dog, a comfortable relationship, and I was utterly miserable. I can’t remember another time in my life that felt that numb. I needed to love something enough to change my life, to quit, to move, to feel again, and that thing was poetry.

EP: Do you have any recollection of the first definition you were given for poetry, perhaps from a teacher or parent?

TB: I don’t remember a first definition of poetry that was given to me, though I remember one I made for myself. In college I discovered the work of Louise Glück, Adrienne Rich, and Sharon Olds, and I remember thinking that poetry should somehow haunt you and heal you at the same time. A great poem makes me feel less alone in the world, but it also pushes around the boxes in the attic and moves in whether you like it or not. I also like Emily Dickinson’s definition of how she defines poetry—“it makes my whole body so cold no fire ever can warm me…If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry.”

EP: Rookery, your first collection of poems, invites the reader in with Bergmanesque portrayals of characters that are quietly cinematic and marked by the strange and threatening: “My mother told me it’s always the best swimmers / who drown,” “We found a dead cub in the snow, / something so innocent it could not be saved,” “You counted the days by their cold silences. / At night, wolves and men with bleeding hands // colonized your dreams.”

Your second collection Our Lady of the Ruins, however, exists in a more lyric place, an alternate reality charged by ecclesiastical concerns. Can you talk about the shift between the two projects? Despite their differences, both are distinctly Traci Brimhall, and the last poem of Rookery, “Prayer to Delay the Apocalypse,” even seems to take us into the setting and concerns of Our Lady.

TB: The shift occurred in a single poem—“Our Bodies Break Light.” It was the first poem I wrote in Our Lady of the Ruins, and it was also how I knew I was writing a new book. It came as a strange, lyrical, polyvocal gift. I felt kind of shy of my own poem. I wasn’t sure where it had come from or why or if I even wanted that kind of gift. I took my cues for many of the other poems from that poem, and it grew into a glorious mess. In order to make a manuscript out of the subsequent poems, I had to be pretty brutal about cutting poems from the book.

“Prayer to Delay the Apocalypse” turned out to be a prelude to the second book, though I didn’t suspect it at the time. When it comes to obsessions, I can’t seem to help myself. I’ll create writing challenges for myself to steer poems away from the same images, subjects, and language, but those obsessions always sneak in. Lately, most of my poems have ended in rapture. I’m so exhausted by transcendence, but I can’t seem to stop.

EP: What were you reading while writing each collection? Can you narrow it down and, if so, do you feel that those other writers wormed their way into the projects? How so?

TB: That’s a tough one to narrow down. During graduate school when I wrote the greater part of Rookery, I was reading a book of poetry every day. When I wrote Our Lady of the Ruins, I was living in my car and wasn’t reading much but road signs, trail maps, and a few books that were boxed up in a storage unit. I can say that the books that I’ve reread lately that still blow my mind are The Descent of Alette by Alice Notley, Tsim Tsum by Sabrina Orah Mark, Don’t Let Me Be Lonely by Claudia Rankine, and Deepstep Come Shining by C.D. Wright. What keeps me returning to these books is not just their clarity of vision, but each represents something forbidden to me, whether it’s a craft choice, a subject matter, a particular deployment of language. These poets de-center me, and I love them for it.

EP: What are you working on now?

TB: Right now I’m working on poems based on my mother’s childhood in Brazil. It’s not meant to be a biography, but more of a biomythography. I’ve taken stories she’s told me and painted my own obsessions and inventions over them. To quote Eavan Boland in A Journey with Two Maps, I used poetry as “a magic permission to make time a fiction and the imagined life a fact. A way, in other words, of making a visible history answer to a hidden life.”

EP: Have you ever tried working in other genres? How did that go?

TB: I love both fiction and nonfiction, though my attempts at fiction tend to only be a couple of paragraphs and my nonfiction requires section breaks every page or so. I can’t seem to create anything longer without stacking discrete moments on top of each other.

EP: As editors, we all have our pet peeves. Is there one thing—a trend, a technique, etc.—that really irks you when you see it come over the transom at Third Coast?

TB: Since most of my role as editor doesn’t involve screening submissions, I can’t say that I have a pet peeve in the slush pile. My greatest frustration as an editor is having too many ideas and too little time. Since I’m a graduate student working on a graduate student run journal, we rotate positions every year or two. There are tons of things I would love to do with Third Coast, but it’s hard to take the long view when we pass the reins off so quickly.

EP: Now, despite that, what are you excited about in contemporary poetry?

TB: I have to quote Emily Dickinson again and say, “I dwell in Possibility—A fairer House than Prose.” One of the things I’ve loved the most as an editor is reading the selections made by the genre editors. There is an overwhelming amount of brilliant work being written. I love seeing the formal innovations, the language play, and the strange and indelible images that come across my desk. Poetry isn’t dead; it’s growing extra limbs to accommodate all the possibilities.

EP: What’s the next step for you?

TB: I hope what’s next in my own writing is more risk and more joy.

EP: Now, provide us with a question that you’d like us to ask the next poet we interview.

TB: I’m interested in how a writer’s relationship to their work changes over time. Has the process of writing different books felt like serial monogamy? Do poets change their writing practice over time, writing in coffee shops one year and in a converted chicken coop the next? Have their obsessions narrowed in or broadened? Spill the beans, poets!

Traci Brimhall is the author of Our Lady of the Ruins (W.W. Norton, 2012), winner the Barnard Women Poets Prize, and Rookery (SIU Press, 2010), winner of the Crab Orchard Series First Book Award. Her poems have appeared in The Kenyon Review, Slate, Ploughshares, and Best American Poetry. She’s received fellowships from the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing, the King/Chávez/Parks Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Each Friday we will publish a new essay, review, or interview for the 32 Poems Weekly Prose Feature, edited by Emilia Phillips. If you have any questions or comments about the series, please contact Emilia at emiliaphillips@32poems.com.

February 14, 2013

A Valentine from 32 Poems

At 32 Poems we’re suckers for a good love lyric, and this Valentines Day we want to share one of our favorites from Old Flame: the First Ten Years of 32 Poems Magazine. We hope you enjoy Evan Beaty’s “Come On,” and if you’d like to take this to the next level, well, you can pick up your copy of the anthology from the good people at WordFarm here.

Come On

—for Sarah Shepherd

Kick off you sandals; the grass is wet

and will help your blisters. Summers

come quicker the closer you are. Tiptoe

into my arms, murmur the language

of cream and vapor, all agate eye-glint

and rising hum of afternoon. Already

I forget the name of this small, bright stream.

But there is cold chicken in the basket.

Take it out, spread all the good things

you’ve brought before me on the blanket.

Hold ice in your fist and drip the cold melt

onto my shut eyes, where red

and purple phosphenes will burst

from black. I’ll carry you back,

if you like. My hands have grown stronger

because I fight.

Come on, let’s get some dirt

under those pretty red nails,

sugarplum.

↔

Evan Beaty received his MFA from the University of Virginia in 2009. His poems appear in Southern Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Cave Wall, Crab Orchard Review, and elsewhere.