Deborah Ager's Blog, page 10

October 5, 2012

Voodoo Inverso by Mark Wagenaar, Winner of the Felix Pollak Prize in Poetry

Reviewed by Lisa Russ Spaar

Mark Wagenaar’s Voodoo Inverso (University of Wisconsin Press, 2012) reads like far more than a single book. A breviary of talismanic mojo, it ripples with series and meta series—references to fragments and missing leaves from a tome called The Book of the Missing, for instance, make mysterious appearances and, by implication, disappearances throughout the collection. Its formal tropes—gospels, nocturnes, self-portraits, portraits of artists, gacelas—and poetic forms (blank verse, sonnets, sestets, proems, dropped lines, Q & A) are manifold and inventive. The collection is a cosmos, and each of its poems shimmers in at least two realms. On their scriptural surfaces, these dense, intensely musical pieces foreground the minutely attended details of the physical world. Coursing in the background are oneiric depths of loss, allusion, erotic and spiritual yearning, and an obsession with what vanishes and what abides. Wagenaar’s gift resides in his ability to hold these two planes, of attention and affect, in volatile equipoise, allowing them, at ecstatic moments, to exchange the secrets of their sensuous textures and their metaphysical, analogic soundings, “as a well waits / for the once-a-day brilliance of high noon.”

Here is a passage from “Spill”:

Or your love of unlit bridges, the one over the Chickahominy,

above water long before you realize it, the surprise

of the water that darkens us, that hurries us along by holding us

under. It’s that kind of wonder the loon dives into, the nowhere

it makes anywhere, such is its solitude, the shade-sized body

it leaves behind in the water . . . .

. . . What is my only comfort in life

& death, each catechism asks. That I am not my own,

each answers. No wonder the thanksgiving & the leaping deer

in the Song of Songs. And the vineyards, & the beloved.

Petunias, petunias, their scent like Beethoven played backward.

Rust-on-blood purple of the red maple, the linden’s

almost peach-soft timber, the shimmering phosphorescence

of the smoke tree, the mimosa’s spikes. A pumpkin’s

orange blossom like a lone prayer flag, the mile of sun & water

between the dragonfly’s damascene wings, the world

we return to without noticing . . . .

Like the “you” of the poem, the reader glides through a dazzling textual catalog of sensory detail, swept “under” the spell of the poem’s litany and the “wonder” of otherness it implies, a nexus of acute presence and ubiquitous effacement that Wagenaar’s deft rhyme reinforces. Those marvelous petunias, with “their scent like Beethoven played backward,” are a signal that even if the catechism is right, and we are not our own, we are still capable of at least half-creating our experience of the world through language acts of pure imagination.

At a time in which irony, detachment, or a kind of wild-ride velocity of snark and smarts (albeit often fetchingly) prevail in the work of emerging poets, Wagenaar is unabashedly seduced by beauty and concerned with the spiritual stakes of the human body in space and time. In poems like “Slow Migration Toward Ecstasy,”

I don’t know jazz

from God’s ribs, but if the speck in my eye divides the world

in two, re-leaves the oak & makes of them each a dragonfly

against the sun, if it makes of the morning frost

a cathedral in which someone’s trying to pray

but the carollonneur doesn’t know it—hammering the bells

with his fists—the words hallowed be thy name shorting out

as he’s kneeling, thinking if I were a priest I’d be home by now . . . ,

and “Tulip Mania (The New Numerology),”

And the tulips,

the tulips in the field across the street, the ten years

it took the seeds to weave their silk into flowering bulbs,

ten skinny years, ten years of silence. Now walk back

from the light that stole in on the two of you this morning,

on your one body . . . wasn’t there a number

you kept counting to as you awoke? The number of kisses

last night & tulips in the bouquet? Didn’t you

have the feeling that this could only happen

in this place, at that time, that you’d never have another

moment like that in a hundred tulip lifetimes?,

we see not only Wagenaar’s facility for moving between physical and metaphysical realms, but also the way in which he plays with time, slowing it down, showing—as he says in another poem—an entire lifetime’s history in a single strand of hair.

Wagenaar dedicates the last poem, “Moth Hour Gospel,” to the poet Charles Wright, and it is clear in Voodoo Inverso that Wagenaar has been taking his Vitamin W. Like Wright, Wagenaar uses a mix of landscape, literary, philosophical, and ekphrastic allusion, God-hunger, pop-cultural detail, and a keen awareness of language to keep his pilgrim speakers traveling the via negativa and the rue de ecstasy. But these poems are not mere imitations; they possess a unique brand of Yankee sensualism, an enviable musical ear, and a knack for the uncanny, startling image. This poetry is the real deal, working on manifold registers and rife with essential tension and questioning. Wagenaar has “a finger on the seam between wind & the rumor of wind,” and I for one will be leaning in to listen again and again to the poems he spins from that liminal music.

—Lisa Russ Spaar

Lisa Russ Spaar is the author of many collections of poetry, including Glass Town (1999, Red Hen Press), Blue Venus (Persea, 2004), Satin Cash (Persea, 2008) and the forthcoming Vanitas, Rough (Persea, 2012). She is the editor of Acquainted with the Night: Insomnia Poems and All that Mighty Heart: London Poems, and a collection of her essays, The Hide-and-Seek Muse: Annotations on Contemporary Poetry, is due out from Drunken Boat Media in 2013. Her awards include a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Rona Jaffe Award, the Carole Weinstein Poetry Prize, an Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia, and the Library of Virginia Award for Poetry. Her poem have appeared in the Best American Poetry series, Poetry, Boston Review, Paris Review, Ploughshares, Slate, Shenandoah, The Kenyon Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, and many other journals and quarterlies, and her commentaries, essays, reviews, and columns about poetry have appeared or are forthcoming in The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Los Angeles Review of Books, the Washington Post, and elsewhere. She is a professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Virginia.

Lisa Russ Spaar is the author of many collections of poetry, including Glass Town (1999, Red Hen Press), Blue Venus (Persea, 2004), Satin Cash (Persea, 2008) and the forthcoming Vanitas, Rough (Persea, 2012). She is the editor of Acquainted with the Night: Insomnia Poems and All that Mighty Heart: London Poems, and a collection of her essays, The Hide-and-Seek Muse: Annotations on Contemporary Poetry, is due out from Drunken Boat Media in 2013. Her awards include a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Rona Jaffe Award, the Carole Weinstein Poetry Prize, an Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia, and the Library of Virginia Award for Poetry. Her poem have appeared in the Best American Poetry series, Poetry, Boston Review, Paris Review, Ploughshares, Slate, Shenandoah, The Kenyon Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, and many other journals and quarterlies, and her commentaries, essays, reviews, and columns about poetry have appeared or are forthcoming in The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Los Angeles Review of Books, the Washington Post, and elsewhere. She is a professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Virginia.

October 1, 2012

Contributor’s Marginalia: Juliana Gray on “The Dead End” by Dan O’Brien

Children are savage. They aren’t innocent lambs, or miniature adults, and they sure as hell aren’t angels; they’re wild animals that their parents and teachers are trying desperately to tame. Like animals, they sometimes form packs, and haunt the cul-de-sacs and schoolyards with their howls. In my neighborhood, the kids have claimed a patch of woods beside the road where I must walk to work each day. There, they’ve erected a habitat: huts and teepees made of branches covered with sheets of bark shed from diseased elms or frost-cracked silver maples, ringed by logs on which they sit during their councils. The perimeter is fenced by sticks jabbed in the ground. I believe some of the ends are sharpened. Each day I check them nervously, expecting to see a mounted Barbie head or a row of inward-facing chipmunk skulls. If I pass when school is not in session, the children stare, hollow-eyed and silent.

Ugolino, Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

And these children are loved. Their parents send them to Montessori and are raising them in two languages. The children in Dan O’Brien’s poem “The Dead End” are not loved, or don’t recognize their father’s treatment of them as such, and so their savagery is sharper, lonelier. “We hated,” the poem begins, and though the line does continue to a direct object, those first two words encapsulate the children’s daily lives. They hate, and swear, and burn, and run wild in the swamp, as dangerous to themselves and others as any of the boys in The Lord of the Flies. They breathe “emerald fumes” and wear the wet feathers of their down coats. Unlike my neighbors’ kids, these children don’t attempt to recreate a civilization in their wilderness. They don’t tame it; they make it wilder.

But even so, I pity these kids, because in the second stanza O’Brien shows why the kids are so eager to run, to curse and beat each other in that vacant lot. At home, there’s a father who doesn’t love them. This sounds like a cliché, I know, or a sentimental pitfall, but O’Brien pulls it off by treating this father’s cold neglect just as sparely as he does the kids’ violence. “If only/ they’d dredge the old brook,” the father complains, blaming the local government for his children’s condition. The trash-clotted brook used to run clear, he says, before the children were born. He can trace the source of the brook in his memory, but he can’t see that he is the source of his children’s misery.

As for the kids, they’re just trash. And that’s when my sympathies as a reader turn, and I ache for those dirty, violent, nasty children, one of whom will grow up to become the speaker of this beautifully crafted poem.

—Juliana Gray

Juliana Gray’s second collection, Roleplay, won the 2010 Orphic Prize from Dream Horse Press. She teaches at Alfred University in western New York. Her poem, “House of Sleep,” appears with Dan O’Brien’s “The Dead End” in 32 Poems 10.1.

Juliana Gray’s second collection, Roleplay, won the 2010 Orphic Prize from Dream Horse Press. She teaches at Alfred University in western New York. Her poem, “House of Sleep,” appears with Dan O’Brien’s “The Dead End” in 32 Poems 10.1.

September 24, 2012

Contributor’s Marginalia: Donna Lewis Cowan on “House of Sleep” by Juliana Gray

As we lie down to sleep the world turns half away

through ninety dark degrees;

the bureau lies on the wall

and thoughts that were recumbent in the day

rise as the others fall,

stand up and make a forest of thick-set trees.

–From Elizabeth Bishop’s “Sleeping Standing Up”

When I first read Juliana Gray’s “House of Sleep” in the latest issue of 32 Poems, I admired the multiple balancing acts that Gray establishes in this brief and subtle lyric poem: nature versus technology, life versus death, and desire versus keeping still. As in T.S. Eliot’s “Preludes,” or one of Elizabeth Bishop’s many nocturnes (“Sleeping Standing Up,” “Insomnia,” “Love Lies Sleeping”), nighttime is when ordinary objects and activities assume greater meaning, and waking to darkness has an almost surrealistic quality. These night songs capture us at our most primal moments, when we are freed from the world’s eyes, expectations, and trappings.

Gray’s first stanza balances the initially static setting of her home with the intrusion of time:

The walls still hold; the hardwood floors sigh

like dreaming dogs as the night air cools,

but hold their places firm.

By suggesting that “The walls still hold,” Gray creates tension, prompting us to question what force is battering them. Her image of the floors as “dreaming dogs” transports us to our own safe places, and evokes the sounds and feelings of home. The wooden floors – in their tendency to creak, droop, yield to our weight, and bear scratches – reflect their natural origins, are nature transplanted. Like real dogs in their sleep, they are the pulse of the house, holding the other objects steady. In just three lines, Gray creates an intimate and relatable space, and reminds us of how our homes bend to our lives.

The Nightmare, Henry Fuseli

In the second stanza, Gray shows us familiar household objects (remote controls, magazines, tossed shoes), “turn[ed] strange in the blue-green light/of digital clocks.” With these lines Gray suggests that technology is changing what we see, and how we interpret the world. They remind us also that clocks – which for so many years required manual winding, and clicked tick-tocks that mirrored our own heartbeats – are now most often replaced by electronic models that cannot give us that aural reminder of time passing, and require no human intervention to operate.

The third and fourth stanzas spell out the conflict hinted at earlier in the poem, as the speaker awakens to the sensation that time has left her behind:

shouldn’t it have collapsed

without you? Isn’t this betrayal, the world

simply carrying on so easily?

These lines reflect the human fear of not mattering in the larger scheme of things: the disappointment of arriving late at a party at which our absence has not been missed. In spite of all the work we do in our daily lives, our clocks, with or without us, push forward into a new day.

With the final stanza, Gray concludes the poem with a haunting shift:

Empty your bladder, return to your sheeted bier.

Live appliances hum their patient songs,

keeping the nightwatch by pale electric glow.

With their reference to a bier – which repeats the idea of death introduced in the earlier line: “a sleep/so complete it might have been your last” – these lines remind us of our human limitations: in short, the songs that will continue on without our voices. The human elements in the stanza, of visiting the bathroom and returning to bed late at night, are superseded by the hum and glow of electronics. From Bishop’s wind-up clock to the “pale electric glow” of Gray’s counterpart, time and change are the inevitable constants.

—Donna Lewis Cowan

Donna Lewis Cowan’s first book of poems, Between Gods, was published in March 2012. Her work appears in Crab Orchard Review, DMQ Review, Notre Dame Review, and Measure: A Review of Formal Poetry, among other publications. She attended the MFA program in Creative Writing at George Mason University, and lives in the Washington, D.C. area. She blogs about finding poetry in the everyday at betweengods.com. Her poem, “Paris to Rome,” appears with Juliana Gray’s “House of Sleep” in 32 Poems 10.1.

Donna Lewis Cowan’s first book of poems, Between Gods, was published in March 2012. Her work appears in Crab Orchard Review, DMQ Review, Notre Dame Review, and Measure: A Review of Formal Poetry, among other publications. She attended the MFA program in Creative Writing at George Mason University, and lives in the Washington, D.C. area. She blogs about finding poetry in the everyday at betweengods.com. Her poem, “Paris to Rome,” appears with Juliana Gray’s “House of Sleep” in 32 Poems 10.1.

September 17, 2012

Hail Infernal World: Dan O’Brien’s “The Dead End”

” . . . Farewell happy fields. / Where Joy for ever dwells: hail horrors, / hail Infernal world” —Paradise Lost

I hate religious poems. So I was surprised as anyone who hates religious poems could be when I found myself finding a Christian subtext to Dan O’Brien’s wonderful poem “The Dead End” in the current issue of 32 Poems.

There are technically wonderful things about the poem, and I would be remiss if I didn’t mention those. For starters, O’Brien accomplishes a lot in 32 lines. Inside the taut, tightly packaged narrative is a setting, a conflict, a protagonist, a plot of man vs. nature and even a subplot of man vs. man, and a resolution straight out of postmodernist fiction. The language is excited, and each line—more often than not—establishes a question that the ensuing line answers, a deft stroke that simultaneously builds a propulsive urgency to the poem while ratcheting up its tension.

But the poem’s religious underpinnings are what draw me repeatedly back to the poem. The first stanza establishes a post-Fall physical ugliness of the landscape—“tangled / … skeins of wild grapes, skunk / cabbage and moss that soaked / through our soles”—against the haunting emptiness we find at the poem’s close.

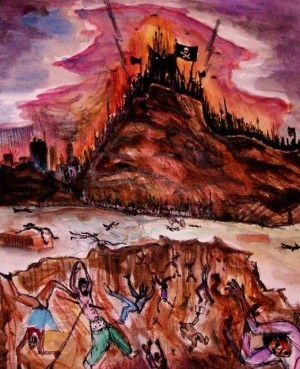

The Fall of Man, Malik Seneferu

O’Brien throws a rhetorical red herring at us in the shape of an initiation narrative that is replete with disobedience, violent imaginings, petting, and potential arson. But the Judeo-Christian implications are hard to ignore. We find out from the poem that what we’re seeing is the aftermath of a world gone to ruin, a corrupted land whose only water supply is “clogged/ with rotting leaves, bottle / glass, condoms and rusted / batteries.” In such an environment, the children of the poem feel compelled to fulfill carnal urges of all stripes. Animalistic “humping” against one another “on discarded cushions / speckled with mold” becomes a kind of grotesque parody of genuine love-making as outlined in The Song of Solomon. And instead of beating their swords into ploughshares, the children take sticks and “beat them into swords” to make war against one another in a reversal of Isaiah 2:4.

As the poem goes on, O’Brien plays out the perpetuity of the fallen world. As the kids habitually attempt to cross the frozen brook that runs through the congested culvert, they repeatedly break through the filthy ice. When they yank themselves free from the sludge, their “soaked down coats [cling] / like shame.” This shame, of course, mimics the feelings first witnessed in Genesis, where—having eaten of the fruit—Adam and Eve’s eyes become opened to the contrast between themselves and God. Likewise, the congested culvert seeping sewage into the swamp contrasts Eden with the fallen world, leaving the children to confront the consequences of the actions in the Garden that result in this world becoming “the dead end” to which the poem’s title points.

Near the poem’s end, the children relay how their “bald father” “decries the local government” about its negligence in regard to the brook. The Old Testament uses baldness in a figurative sense to express the barrenness of the country (see Jeremiah 47:5), so the description is apt for the father, a kind of Adamic character who blames the “government” (an obvious metaphor here) for the condition of the area. If the government would simply reverse its decision, the brook “would flow clean and clear / … like it did in the days / before [the] six [children] were born.” This call from the father for a return to paradise that predates the birth of his six children is particularly revealing.

Or maybe that reading is all a bunch of hooey, and the poem is only about a disgruntled father with six obstinate children and nothing more.

At any rate, O’Brien’s pulls together a fine narrative poem, one like I wish I saw more of coming across my desk at Linebreak. Too often narrative poems forget that they’re poems, and attention to sound and rhythmic urgency gets subjugated to a narrative that lumbers from point A to point B. “The Dead End” suffers none of these qualities, and brings to me the only hell I know: reading a poem that I wish I’d written.

—Ash Bowen

Ash Bowen’s poems have appeared in Quarterly West, Black Warrior Review, Best New Poets, and elsewhere. He is co-managing editor of Linebreak, and his poem, “My Love Is for the Weatherman,” appears with Dan O’Brien’s “The Dead End” in 32 Poems 10.1.

Ash Bowen’s poems have appeared in Quarterly West, Black Warrior Review, Best New Poets, and elsewhere. He is co-managing editor of Linebreak, and his poem, “My Love Is for the Weatherman,” appears with Dan O’Brien’s “The Dead End” in 32 Poems 10.1.

September 10, 2012

Contributor’s Marginalia: Corinna McClanahan Schroeder on “Paris to Rome” by Donna Lewis Cowan

At the heart of Donna Lewis Cowan’s poem “Paris to Rome” is the jarring and yet ultimately productive mystery of a train ride. Indeed, from the beginning, before the train is ever boarded, this travel poem opens a space in time in which the unexpected can occur. While the collective “we” had hoped, like many tourists, to “dash between // the tomes of history, just to see / the sights,” the speakers “arrived [in Paris] after the Iraq invasion” but “before the European heat wave.” It is here, in between the “before” and “after,” and during “the usual transit strike,” that a gap forms, opening normal, scheduled time to actual, lived time and opening expectation to experience.

By the poem’s sixth line, the speakers find themselves on the train, “doubled up / in the cars, too many of us.” Even though the tourist experience of traveling among foreign countries by train is relatively common, Cowan’s poem reveals that there is nonetheless something unsteady, something unfamiliar, about that experience, for the “too many of us” find themselves “awake in the sleeper.” So too, here, the poem switches abruptly into present tense, the train’s unsteadying effect carried over into written effect as the poem itself—long and thin—journeys down the page.

Train Ride, Bob Dornberg

In his fascinating study The Railway Journey (University of California Press, 1977), historian Wolfgang Schivelbusch explores the new experience of train travel in the nineteenth century and how it affected passengers who were used to much slower forms of overland travel—like the walk, the horse ride, and the stagecoach. Indeed, early passengers who used the new train technology found themselves strangely objectified by the experience, turned from a person into a parcel, as a popular nineteenth century saying phrased it. So too rail travel changed travelers’ sensory perceptions dramatically—not only did the smells and sounds that might accompany a long coach ride disappear, but travelers’ visual perceptions were changed entirely. They could no longer look ahead; rather, “all they saw was an evanescent landscape” (55). Schivelbusch quotes Victor Hugo’s description of the view from a train window in a letter dated 22 August 1837:

The flowers by the side of the road are no longer flowers but flecks, or rather streaks, of red or white; there are no longer any points, everything becomes a streak; the grainfields are great shocks of yellow hair; fields of alfalfa, long green tresses; the towns, the steeples, and the trees perform a crazy mingling dance on the horizon; from time to time, a shadow, a shape, a spectre appears and disappears with lightning speed behind the window: it’s a railway guard. (qtd. 55-56)

The train car window, then, offered a new way of seeing the world, and a new way of seeing the world produces an entirely new world, a strange world, even a discomforting world, as Cowen’s speakers, far from home, pressed against strangers, and riding through foreign terrain, similarly realize:

We go deeper into countryside

and houses recede further

from the tracks, as if

this is not what was wanted,

or not entirely—

Suddenly, the entire project of travel, the speakers’ journey and their intention for that journey, is thrown into question by the experience of train travel—in short, their control is gone. The speakers feel as if the landscape itself is pulling back from the train, from tourists readings maps and “rendering Saint Cloud // a Yankee god of precipitation.” “What was it for?” the speakers wonder, the heavy ambiguity of “it” serving to create for the reader his or her own unsteadying experience.

Speeding Train, Ivo Pannaggi

And yet, self-doubting and “sealed” from the world’s sounds, the speakers find that the train’s rhythms “steep in our skin.” The physical experience of riding affects them, first jarringly and then in a kind of transformation: “Call it antidote,” the speakers say. This antidote—being made uncomfortable, being made to see anew, having one’s expectations give way to the possibilities of present experience— redeems the journey. In this way, Cowan captures the strangeness and wonder that results from the discomfiture of the train ride and from travel more generally, and I love that, even as the poem ends, the train barrels on through the unfamiliar landscape, “the track divined / and steady over rough terrain.”

—Corinna McClanahan Schroeder

Corinna McClanahan Schroeder’s poetry appears or is forthcoming in such journals as Gettysburg Review, Shenandoah, Tampa Review, Poet Lore, and Blackbird. She is the recipient of a 2010 AWP Intro Journals Award in poetry and was named a finalist for the Ruth Lilly Poetry Fellowship in 2011. She holds an MFA from the University of Mississippi and is currently pursuing her PhD at the University of Southern California. Her poem, “Years Later, I See My Old Self Stumbling Down the Street,” appears with Donna Lewis Cowan’s “Paris to Rome” in 32 Poems 10.1.

Corinna McClanahan Schroeder’s poetry appears or is forthcoming in such journals as Gettysburg Review, Shenandoah, Tampa Review, Poet Lore, and Blackbird. She is the recipient of a 2010 AWP Intro Journals Award in poetry and was named a finalist for the Ruth Lilly Poetry Fellowship in 2011. She holds an MFA from the University of Mississippi and is currently pursuing her PhD at the University of Southern California. Her poem, “Years Later, I See My Old Self Stumbling Down the Street,” appears with Donna Lewis Cowan’s “Paris to Rome” in 32 Poems 10.1.

September 3, 2012

Contributor’s Marginalia: Jessica Piazza On “Will You Tell Me if You Will” by Marielle Prince

Right now, in order to begin writing a few words on Marielle Prince’s fantastic poem “Will You Tell Me if You Will,” I’m pulling myself away from Facebook, where I’m embroiled in an entirely useless flame war about women’s reproductive rights and the misogyny of current conservative politics. Now, I wouldn’t usually mention this. (Academia has almost managed to beat the conversational and personal voice out of my serious writing.) I bring it up, though, because it strikes me as apropos that I’m having this particular political conversation while thinking about this particular poem.

It might seem like a stretch, I admit. But I’m on maybe my sixth reading of Prince’s poem, and somewhere around the third read it started seeming sort of…well, not sort of, but blatantly and uncompromisingly…feminist 1. The female subject of this poem’s experience is simultaneously brazen, complicated and confused, which makes the poem exciting. But it is also a quintessentially female experience, which makes the poem truly relevant.

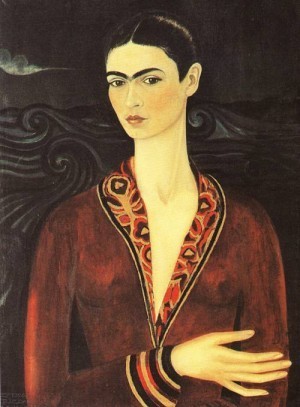

Self Portrait Wearing a Velvet Dress, Frida Kahlo

The piece cleverly begins with “the question,” an unspecified query that the subject of the poem puts on like jewelry, like an accessory. This unspoken question is sometimes stylized (“penciled in around her eyes”), sometimes organic to her environment (swaying like “chimes in a soft breeze”) but—like a face full of makeup or a firm handshake—always inseparable from the identity she must show to the world. That Prince omits the actual question is a stroke of artistic brilliance; by doing this, the female subject in red lips and kohl eyeliner becomes every woman, and the question becomes any inquiry into identity and artifice 2. All at once, the subject of the poem embodies that ubiquitous feminine investigation: who am I and who should I be to the world?

But just when you think you know where you stand in this poem, the second stanza shifts everything. The speaker of the poem is no longer looking at the “her” of the subject, no longer watching her wield her well-coifed and mysterious question. Now, the speaker of the poem is looking at, discussing, dissecting “you.” You are now implicated in this question and, more importantly, in making sure the question is examined and answered.

The you in this stanza isn’t doing such a great job at it, either. “You saw the question.” “You covered it quickly” in shame. You “didn’t see.”

Is the “you” just us? The readers? Or is there a specific object that the speaker is addressing: a stand-in for the male gaze, for some douchebag ex-boyfriend, for her father or mother or society in general? Who knows? The point is, by pointing outward, the poem smartly loosens the net of its observation just enough to invite us personally in. We’re caught in it now, forcing ourselves to answer our own overwhelming questions about how we see and judge others, women, competition, men, the world 3.

By the last stanza, we’re able to see the many ways the female subject might be subdued or restrained from answering her question, and from fighting against objectification. She might be blinded to the question’s existence in the first place, or brainwashed into believing it is unimportant, or distracted by the need to be attractive, or by the need to please others.

The last line, though, is what brings these ideas home, while introducing the most obvious, but also the saddest, possibility. Prince ends by saying that the question that hangs in the air might be “an alarm set to wake her the same each day.” It’s this resignation—this assertion that life’s daily goings on can put even the most important questions to rest—that feels tragic and true, together. Maybe that’s why I thought of Eliot’s “Prufrock” poem in the first place…he ends it with ”Till human voices wake us, and we drown,” indicating that the numbing spin of daily life continues, despite the metaphysical goings-on in our heads. And while this is true for both men and women, Prince’s last line, for me, feels specific to women. Many of us wake up each day expected to put our needs aside for other people (children, of course, but family too, and bosses, and…you fill in the blank). Many of us do that willingly, the expectation fully our own. But either way, in this light ending the poem on the alarm clock and the similarly of the speaker’s days seems especially poignant.

Corpus Speculorum Etruscorum

Now, a caveat. This commentary is almost certainly over-politicized; I attribute this to my state of mind while writing it. What I do love, however, is that poetry can work like that. Prince might have meant this as an awesomely engaging and well-disguised feminist manifesto, or she may have been aptly describing a time in her own life during which she felt especially powerless, or she may be commenting on someone we don’t know, or no one at all. It might be about some chick she met in a bar, or about her mom, or about my mom. But that is not the point. The greatest poetry allows you—the reader— to put your own most present passion on its shoulders. This poem fulfills that in spades, with room on its shoulders to spare.

Also, it’s a kick ass read. Seriously 4. Poems that live in a box do very little for me; the poems I like best sweat, they breathe and pant and curse and cry and cackle. I’m a fan of poetry that asks you to do linguistic work, of poems that use white space and prose form in a distinctive way, of poets who put it all on the line. This poem and this poet do all of that, and I, for one, am a new Marielle Prince fan.

↔

1. I truly hope she doesn’t blanche at that word the way some do—the way I sometimes do—since by saying it I’m complimenting, above all else, her artistry. Because this poem does what most poems, at their core, seek to do: it offers a window into a truth of experience, without sugar coating, but also without politicking.

2. Like Eliot’s “overwhelming question” in “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufock,” Prince wants us not to “ask what is it.” In lieu of examining the question, Prince invites us on a journey into the poem subject’s experience. The difference here, though, is significant. In Prufrock, we are along for the ride inside the subject’s head, but not in Prince’s poem. Both have elements of stream of consciousness, but it’s important that Prince’s speaker is looked at, she is not, like Prufrock, doing the viewing. This objectification compounds my point, as it’s so very indicative of the artistic (and political) gaze toward women and their worth.

3. Okay. I’m going a little far, I know. But that’s what staring at a cool poem for a long time can do. And this is, undoubtedly, a cool poem. So just indulge me for another few hundred words.

4. Despite the seriousness of the dissection I’ve done, I should mention that my least favorite thing about contemporary poetry is that is rarely seems like fun. I don’t mean funny, or even silly….I’m not limiting poetry like that. I understand its capacity to tackle the really hard subjects. However, when a poem is fun for the writer, when you can really see the writer getting a kick out of it, the reader also has fun reading it, regardless of its relative somberness or levity. And I had fun reading this.

—Jessica Piazza

Jessica Piazza‘s first full-length collection of poems, Interrobang, is forthcoming from Red Hen Press in 2013. She was born and raised in Brooklyn, NY, and is currently a Ph.D. candidate in English Literature and Creative Writing at the University of Southern California. She is co-founder of Bat City Review, an editor at Gold Line Press, a contributing editor at The Offending Adam and has blogged for The Best American Poetry and Barrelhouse. Her poem, “Strict Traffic,” appears with Marielle Prince’s “Will You Tell Me if You Will” in 32 Poems 10.1.

Jessica Piazza‘s first full-length collection of poems, Interrobang, is forthcoming from Red Hen Press in 2013. She was born and raised in Brooklyn, NY, and is currently a Ph.D. candidate in English Literature and Creative Writing at the University of Southern California. She is co-founder of Bat City Review, an editor at Gold Line Press, a contributing editor at The Offending Adam and has blogged for The Best American Poetry and Barrelhouse. Her poem, “Strict Traffic,” appears with Marielle Prince’s “Will You Tell Me if You Will” in 32 Poems 10.1.

August 27, 2012

Contributor’s Marginalia: Maria Hummel on “Moment of Dante” by Paul Bone

I took a Dante seminar during my senior spring in college, part of a small group of devotedly nerdy students that clustered around a rectangular table. Most of the time, we pretended to understand more than we did, and we struggled through the cantos with the green enthusiasm of the crocuses and daffodils surging up outside.

Suddenly it was May, and we were halfway through Purgatory when a sophomore named Carmen broke in.

“I’m sorry. I know we’re supposed to be all knowledgeable here, but I JUST DON’T GET IT,” she said. “I wasn’t raised to believe in anything, any church or whatever, and every week when we talk, I feel like there’s some layer I’m supposed to be seeing. And I can’t.” She tossed up her hands. “How am I supposed to know what’s really going on?”

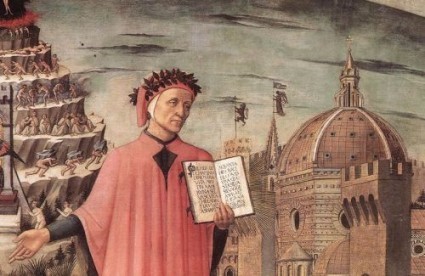

Dante Alighieri in a painting by Domenico di Michelino

When I read Paul Bone’s marvelous “Moment of Dante” in Vol. 10, No. 1, I remembered Carmen, and her justified sense of unfairness at the old Florentine poet for tying her mind in knots about 14th-century transcendence. Her outburst touched on the great and unanswerable problem of how new generations experience the literature of the past, and it launched the best debate we had that spring.

Bone’s poem beautifully examines the same issue, move from disorientation to revelation in a trio of distinct acts that echoes the three-part structure of the Divine Comedy.

In the first act, a speaker describes teaching Dante to students who are sick of him, “of journeys.” The act ends when, in a notably end-stopped line, the electricity in the building cuts off. It is a blackout.

The second act shows the students pulling out their phones and flipping them open. The poem doesn’t ask what they’re searching for. Exposition is over now, and Bone shifts into the lyric mode, drawing out time with imagery and rhythm. His focus moves to the devices’ light, and as it moves, his meter goes mostly iambic: “The lights from all the phones, blue as lapis, / brought just their faces back from the abyss,” he writes, using lapis and abyss to echo off each other in a pleasurable reversal of stresses. All at once, in the haloed light, the students’ heads appear to detach from their bodies. The self departs it corporeal prison.

This gorgeous image could end the poem, as Dante leaving Purgatory and moving to Paradise could have ended the Divine Comedy, leaving heaven up to the reader’s imagination. Yet like his forebear, Bone goes on. His conclusion deepens the question of revelation, and brought me back to thinking about Carmen.

“The precise moment when the moment vanished / was when they began to look for each other,” Bone writes, and describes the students swinging the lights from their phones around until “behind, beside / the edges of their spheres united / and they remembered they were not alone.” The power comes back on. The students chatter. And “there was no more lesson that day.”

The spell of light and dark is broken, and broken in a way that reminded me painfully of the isolation of Carmen and most contemporary readers. Unlike the Florentines of Dante’s time or the Elizabethans of Shakespeare’s or even the Americans of Whitman’s, we do not have a common sacred text, and therefore our experiences of literary transcendence are rare and unshared. “Behind, beside,” Bone writes when he describes the students’ lights. Not “with” or “among.” The layer of collective revelation that Carmen couldn’t see simply isn’t there anymore. What this means for poetry is still hard to fathom. We may have the Comedy, but we’ve lost the Divine.

Bone alternates between end-stopped lines and enjambment to underscore the tri-part structure of his examination of the lost sublime. The enjambed lines give the lyric moments their flow, their sense of transition, and eventual transcendence. The three end-stopped lines create the plot:

Just then the power in the building failed.

It happened all at once, reflexively.

And then the lights came back. A nervous chatter.

“Moment of Dante” is the last poem in this issue, making it a kind of meta-commentary on the other thirty-one. I wonder sometimes, as a 21st century poet, about our current cultural position, stuck between the “lights” and the “nervous chatter” of our time. What does it mean that 32 Poems’ parting shot is about people failing to read but finding connection anyway? I don’t know, but I can say that I admire Paul Bone and everyone involved in the issue for eloquently capturing so many distinct pleasures and doubts in our ongoing search for meaning.

—Maria Hummel

Maria Hummel’s poetry and prose have appeared recently in Pushcart Prizes XXXVI, Narrative, The Sun, and Missouri Review. She lives in San Francisco with her husband and son. Her poem, “The Unicorn,” appears with Paul Bone’s “Moment of Dante” in 32 Poems 10.1.

Maria Hummel’s poetry and prose have appeared recently in Pushcart Prizes XXXVI, Narrative, The Sun, and Missouri Review. She lives in San Francisco with her husband and son. Her poem, “The Unicorn,” appears with Paul Bone’s “Moment of Dante” in 32 Poems 10.1.

August 24, 2012

Hot off the Press: Lee Upton’s Essays and Reflections on Creativity and the Life of the Artist

The title of Lee Upton’s new book, Swallowing the Sea: On Writing & Ambition, Boredom, Purity & Secrecy (Tupelo Press), tells you everything you need to know about what is to come without giving anything away. If the title feels irresistible, that’s at least in part because it is in itself a micropoem that gets swiftly and surely to the heart of who a writer is. In this book, at once fast-moving and deep-dwelling, Upton constantly circles and vivisects each of the abstractions in her title. More than anything, she explores the notion of ambition, trying to understand its negative implications and to celebrate what she sees as an ultimately creative, engendering force. She describes her own early forays into language, which she conceives as intimately wedded to ambition, and describes with particular poignancy her memories of communicating with her father, who lost his hearing over the course of her childhood. Although the story is tinged with pain, she remembers, “To be heard by him meant that all of us in our family had to weigh our words.” This is both an origin story and an ars poetica, describing one fundamental problem art addresses and one it creates: the desire to be understood and the best way to achieve it through the media available. She credits ambition with seeing not only her through these difficulties, but also Dickinson, Kafka, and everyone else who takes up the pen. Ultimately she argues that ambition unites artists in a kind of brotherhood.

The book is not all apologetics: alongside Ambition lives Purity. This seeming virtue brings up a string of contradictions and complications that Upton delights in unpacking. “The rhetoric of purity can be connected to horrific violence,” and “We don’t often use the phrase ‘a clean mind,’” are two examples of how an idea important to every writer is astonishingly beset with connotations at variance with one another. All this despite the world’s seeming indifference to the notion itself. She describes a strong impulse she felt after the birth of her daughter “to purify [her] writing.” She gives the example, “I neglected to respect the vitality of the vernacular. I pared away draft after draft. Only gradually did I re-learn how to allow more life into my writing—that is, more of language, graced with its inevitable impurities.” She links this strongly to new motherhood, mentioning the obsession of making a dangerous, unpredictable world safe for a baby, and also to womanhood itself, discussing Plath and Anne Carson’s explorations of women in their own art and in classic culture. I found this fascinating even beyond those links as a description of the paths we take as writers. We repeatedly confront challenges that seem to change every moment, and which almost always originate within us. The challenge of removing impurities without removing the quicksilver of life itself is one of the great ongoing challenges of craft, and Upton gives compelling, illuminating testimony of that.

The book is not all apologetics: alongside Ambition lives Purity. This seeming virtue brings up a string of contradictions and complications that Upton delights in unpacking. “The rhetoric of purity can be connected to horrific violence,” and “We don’t often use the phrase ‘a clean mind,’” are two examples of how an idea important to every writer is astonishingly beset with connotations at variance with one another. All this despite the world’s seeming indifference to the notion itself. She describes a strong impulse she felt after the birth of her daughter “to purify [her] writing.” She gives the example, “I neglected to respect the vitality of the vernacular. I pared away draft after draft. Only gradually did I re-learn how to allow more life into my writing—that is, more of language, graced with its inevitable impurities.” She links this strongly to new motherhood, mentioning the obsession of making a dangerous, unpredictable world safe for a baby, and also to womanhood itself, discussing Plath and Anne Carson’s explorations of women in their own art and in classic culture. I found this fascinating even beyond those links as a description of the paths we take as writers. We repeatedly confront challenges that seem to change every moment, and which almost always originate within us. The challenge of removing impurities without removing the quicksilver of life itself is one of the great ongoing challenges of craft, and Upton gives compelling, illuminating testimony of that.

Upton reckons with the idea of “Swallowing the Sea” early in the book, writing, “Even before writing any notes, I had wanted to call this book Swallowing the Sea to suggest and honor the wildly outsized but exhilarating ambition that the act of writing can generate, and as an image of the love of impossibility, the love of something astonishing achieved through the imagination.” The book itself is such an attempt at containing the limitless, and in many ways does touch the impossible. Surely to make sense of the experience of being a human being, much less a writer, is a task one can never complete. Yet, through its simultaneously scholarly, kinetic and musical journeys through Upton’s imaginative universe, the book is again and again satisfyingly accurate in its portrayal of an artist’s inner life, and defends and celebrates that life in a meaningful and enlivening way. We are treated to not only her relationship to these words and concepts, but also to her great love of writing, which ranges from Milton to detective fiction. The writing is at every moment charmingly irreverent and dead-sincere, a book, first and foremost, for writers.

—Jasmine V. Bailey

August 21, 2012

From the Archives: “A Starlit Night” by B.H. Fairchild

We’re digging deep this week, back to one of our favorite pieces from the journal’s first issue in the summer of 2003.

We’re digging deep this week, back to one of our favorite pieces from the journal’s first issue in the summer of 2003.

B. H. Fairchild, the author of several acclaimed poetry collections, has been a finalist for the National Book Award and winner of the William Carlos Williams Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award. He lives in Claremont, California.. His ”A Starlit Night,” originally published in 32 Poems 1.1, was later featured on The Writers Almanac and appeared in Fairchild’s 2004 Early Occult Memory Systems of the Lower Midwest.

A Starlit Night

All over America at this hour men are standing

by an open closet door, slacks slung over one arm,

staring at wire hangers, thinking of taxes

or a broken faucet or their first sex: the smell

of back-seat Naugahyde, the hush of a maize field

like breathing, the stars rushing, rushing away.

And a woman lies in an unmade bed watching

the man she has known twenty-one, no,

could it be? twenty-two years, and she is listening

to the polonaise climbing up through radio static

from the kitchen where dishes are piled

and the linoleum floor is a great, gray sea.

It’s the A-flat polonaise she practiced endlessly,

never quite getting it right, though her father,

calling from the darkened TV room, always said,

“Beautiful, kiddo!” and the moon would slide across

the lacquered piano top as if it were something

that lived underwater, something from far below.

They both came from houses with photographs,

the smell of camphor in closets, board games

with missing pieces, sunburst clocks in the kitchen

that made them, each morning, a little sad.

They didn’t know what they wanted, every night,

every starlit night of their lives, and now they have it.

August 13, 2012

Contributor’s Marginalia: Paul Bone on the “The Unicorn” by Maria Hummel

On the first reading of Maria Hummel’s “The Unicorn,” it’s as if a beleaguered workshop instructor has said, “All right, you want to write a poem about unicorns, here’s how to do it.” The poem practically embraces some sentimental tropes of bad poetry: a mortally wounded fantastical animal (mermaid, hippogriff); bedside vigil for a sick child; dialogue clearly directed to be shouted; grim, murmuring bystanders with dire prognoses. Here indeed in Hummel’s poem are all the exaggerated and completely implausible materials of a nightmare that hardly ever translate into a good poem, except for here. And why is that? Because it is able to simultaneously satirize and sanctify those tropes while drumming up real pathos. And how about the how?

I’m reminded of Bruce Bond’s commentary in this very blog on Jessica Piazza’s “Strict Traffic,” another fine prose poem in this issue, when I read Maria Hummel’s “Unicorn.” As Bond suggests, prose poems offer the best of both worlds, speech and music, “walking and dancing,” informality and high formal feeling. In “The Unicorn” we find the demotic and the demonic as well, but in a slightly different way than a mix of casual innuendo and intense connection.

Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Chastity with the Unicorn

If not the direct aesthetic heir of the prose poems of Russell Edson, or something like Charles Simic’s The World Doesn’t End, or even the deadpan gothics of Stephen Dobyns’ Cemetery Nights, “The Unicorn” nonetheless shares their willingness to play out a narrative strand to its fantastical if not logical conclusion. But whereas Dobyns’ dark fables often begin with a quotidian, almost hackneyed premise—a man comes home to find his wife in bed with the milkman—and builds to more outlandish denouements, such as a dog being shot for the sins of the adulterous couple, Hummel’s poem begins with an outlandish premise and brings us down to what should be an unforgivable resolution, that a unicorn will be sacrificed so that an evidently terminally ill child may live.

It has all the hallmarks of good fiction—the introduction of a foreign element into the status quo, which creates conflict and struggle; good pace; the realistic detail (“horn scraped the paint on the wall”) inside of an unrealistic premise; summarized dialogue (lost), which itself heightens the tension toward a climax. These prosaic elements, in fact, more than the surreal, are the poem’s strengths.

I’m even more fond of the poem’s borrowings more broadly from prose, and not just in the sense that the language is “straightforward.” I don’t mean merely poetry that is primarily narrative, either. What I mean is that the willingness to say the ordinary within more nearly lyric poetry is laudable, the rhetoric of prose amid the lyric impulse, the essayistic aside or rumination, a quick characterization, an unapologetic run of 3 or 4 lines dedicated only to setting a quick scene. I think of B.H. Fairchild’s long narratives, loose, blank verse fictions and lyric meditations that are luminous for this very reason, that they transform the ordinary detail and also have the tremendously effective impact of voice, of a human voice assembling the wreckage of memory and experience. Here Hummel has taken a jeweler’s approach to story, but still I’m attracted to its use of prosaic gestures to make something compressively poetic.

—Paul Bone

Paul Bone is the author of Momentary Vision of the Assistant Meteorologist (Uccelli, 2005) and Nostalgia for Sacrifice (David Robert Books, forthcoming). He is chair of Creative Writing at the University of Evansville and co-editor of Measure. His poem, “Moment of Dante,” appears with Maria Hummel’s “The Unicorn” in 32 Poems 10.1.

Paul Bone is the author of Momentary Vision of the Assistant Meteorologist (Uccelli, 2005) and Nostalgia for Sacrifice (David Robert Books, forthcoming). He is chair of Creative Writing at the University of Evansville and co-editor of Measure. His poem, “Moment of Dante,” appears with Maria Hummel’s “The Unicorn” in 32 Poems 10.1.