Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2518

October 26, 2010

The Reagan Precedent

This is a bit of an aside in a column that's primarily about legislative strategy, but I think Mark Schmitt is expressing a widespread tendency to take an undue level of comfort from the precedent of Ronald Reagan's first term:

Many of the White House's political troubles can be entirely explained by the economy, of course, since they are exactly comparable to Ronald Reagan's unpopularity with similar levels of unemployment in 1982. But when the economy recovers, as it will, and his presidency regains its footing, Obama — and we — will need a whole new theory about how to make government work without losing the bigger vision.

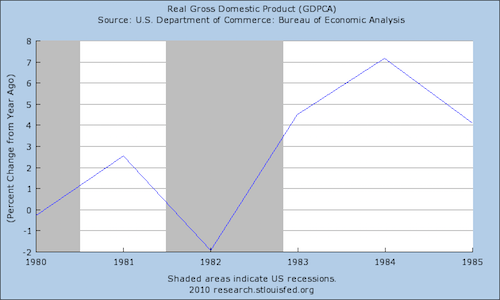

Check out the level of GDP growth associated with the "morning in America" recovery:

By contrast, the CBO is projecting (PDF) 2.1 percent real GDP growth for 2011. Now it's true that CBO's estimate is on the pessimistic side. We might well do better than that. But the point I would make is that there's nothing inevitable about a robust catch-up recovery. We entered the early 80s recession with high inflation and very high nominal interest rates. When Paul Volcker was satisfied that inflation was whipped, he implemented sharp reductions in nominal interest rates and growth came roaring back. But ever since nominal rates hit zero, the Fed's been stumbling around, real rates are still pretty high, and nobody seems to have any politically feasible ideas about how to do better.

Insider Trading

Andrew Ross Sorkin takes a look at some newly expansive definitions of insider trading:

Late last month, the Securities and Exchange Commission brought an unusual and colorful insider-trading case: It accused two employees who worked in the rail yard of Florida East Coast Industries and their relatives of making more than $1 million by trading on inside information about the takeover of the company.

How did these employees — a mechanical engineer and a trainman — know their company was on the block?

Well, they were very observant.

They noticed "there were an unusual number of daytime tours" of the rail yard, the S.E.C. said in its complaint, with "people dressed in business attire."

He summarizes the new attitude as "the S.E.C. is no longer just making sure that employees are not abusing their position and breaching their fiduciary duty; it is focused on making sure the markets 'feel' fair."

This doesn't strike me as change for the better. There are two kinds of functions equity markets serve. One is that they aggregate information and channel capital to useful activities. The other is that they serve as casinos that generate a "take" for various brokers and the like. You can make the case that some kinds of restrictions on insider trading are necessary in order to help equity markets serve their former function. But the latter function isn't something the government should be getting involved with.

Of course if I were running the stock market I would want small investors to "feel" that the market is fair. But the market is not, in fact, fair. And no quantity of S.E.C. policing is going to make it fair. If you want "fair" you should buy an index or some government bonds. The most valuable role the government could play would probably be to slap a giant "you probably shouldn't invest here" sticker around the whole thing. Then firms and the stock market itself would face the somewhat challenging problem of inspiring investor confidence in the integrity of their operations, rather than getting the government to do it for them. Something like the observant railroad employees, by contrast, is exactly the kind of aggregation of information that we're looking for in markets.

School Quality is Hard, Even in Early Childhood

I mentioned this once before, but I think that people sometimes exaggerate the contrast between what we know about charter schools and what we know about pre-kindergarden. In both cases, what we have are examples of highly effective intervention alongside other examples of lower-quality intervention and continued debate over what really works.

For a taste, check out Sara Mead on pre-K teacher quality:

These concerns are underscored by developments over the past several years. On the one hand, an important 2007 study found limited correlations between pre-kindergarten teacher's educational credentials and observed classroom quality or child outcomes, raising questions about the established orthodoxy in the field. At the same time, new models–most notably the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS)–have emerged that offer valid and reliable measures of pre-k instructional quality based on what teachers actually do in the classroom–and are correlated with student learning outcomes. And there is also evidence that certain types of professional development are effective in improving the skills and effectiveness of pre-k teachers, whether or not they have a bachelor's degree–such as high-quality coaching linked to CLASS and the combination of professional development, coaching, and progress monitoring provided through the Texas Early Education Model.

None of that is to say that pre-K boosters are wrong. On the contrary, they're completely correct. High quality pre-K programs appear to have large benefits. But the situation is no different from the one facing K-12 education—high quality is both extremely valuable, somewhat hard to come by, and best obtained if we judge providers on their results rather than by assuming we know which inputs are the best.

Yes, China's Currency Policy is a Problem

(cc photo by cliff1066)

I think a lot of the discussion of the issue has somewhat overstated the extent to which Chinese currency manipulation is a problem for the United States. So I guess it's John Cochrane to the rescue with an op-ed that manages to wildly understate the issue. He starts with the odd premise that we should do a libertarian analysis of trade with a large dirigiste economy with a state-controlled banking sector:

How does anyone know if a currency is "undervalued" or not? The economists hidden away in the sub-basements of the IMF may try to decide what currencies "should be" worth across vastly different countries, but this is a hopeless task. Is $2 a day the "right" wage in China, or should that be $2.20 per day because the currency is "undervalued?" Good luck.

Indeed. Why not just leave the valuation of the currency up to the market? But has Cochrane not heard of the Chinese capital controls that are the crux of the issue here? The reason we don't just leave this up to the market is that the Chinese government doesn't let the market set the value of its currency. Instead the government sets the price. So while IMF economists can't get the "right" value as well as markets might, they can still say "this price-setting is being done in a distorting way."

Next graf, though, it seems Cochrane understands this perfectly well:

Why push China to manipulate its currency upward, but ignore its capital and exchange controls? We should push China to abandon those controls instead. A freely pegged currency is a great idea, especially for a fast-growing, trade-based economy with a weak central bank like China.

Why push China to manipulate its currency upward, but ignore its capital and exchange controls? Because nobody is doing this. What we're asking China to do is to relax those controls. Should we push China to "abandon" those controls instead of asking them to relax them? Well, it's hard to say what difference that would make.

To motivate the idea that there's a disagreement here, Cochrane then finds himself bizarrely denying that Chinese bond purchases are an effort to manipulate their currency level. Like Brad DeLong I would urge him to discuss this with someone. Go to China. Talk to their Commerce Ministry. Talk to their Foreign Ministry. Ask a businessman. Nobody is confused about this. The policy is export-led growth and that means not allowing the currency to appreciate too rapidly.

Fed Succeeding in Boosting Inflation Expectations

The thing you need to understand about the anomalous negative interest rates on inflation protected bonds is that this is the plan. Given the state of the economy we need negative real rates to produce growth. People have become extremely risk-averse, and we need to find out exactly how risk-averse they are. If the returns on risk-free investments are guaranteed to be negative, then suddenly riskier investments—i.e., investments in growing "real" economic activity—start looking better.

Meanwhile, I noted yesterday that I think Paul Krugman tends to overestimate how difficult it is for the central bank to generate inflation. And, indeed, today he says he's puzzled by why markets are reacting so strongly to the QE2 talk and suggests they're making a mistake.

Maybe they are, but I think what we're basically seeing is the potency of the communications channel. In a case like this, if the markets converge on a higher expectation of inflation then that can easily become a self-fulfilling prophesy through the "bootstrap" mechanism described in his 1998 paper (PDF) "It's Baaaack! Japan's Slump and the Return of the Liquidity Trap."

If the central bank can credibly commit itself to pursue inflation where possible, and ratify inflation when it comes, it should be able to increase inflationary expectations despite the absence of any direct traction on the economy via current monetary policy. Indeed, if one views monetary policy in terms of nominal interest rates, a credible commitment to inflation can seem to be a pure bootstrap policy: interest rates never actually need fall, all that is required is a promise not to raise them when the economy expands and prices begin to rise.

He then observes, correctly, that "How to actually create these expectations is in a sense something outside the usual boundaries of economics."

This is an interesting research issue crossing over social psychology, political science, and economics that I think we don't know very much about. But we should at least be open to the possibility that it's very easy to generate these expectations as long as you actually want to. The key question now is will the powers that be try to "reassure" markets of their commitment to fighting inflation, or will they embrace an increasing price level as part of the solution to our problems.

Will Divided Government Lead to Deficit Reduction? Will It Lead to Anything?

At first blush "divided government" seems like a recipe for endless gridlock. At second blush this isn't really correct. A lot of significant legislation, from No Child Left Behind to the creation of a Medicare prescription drug benefit to the Balanced Budget Agreement of 1997, the 1996 Telecommunication Act, "welfare reform," etc. happened in the 1990s and 2000s under conditions of divided government. And David Mayhew's book Divided We Govern surveys the 1946-2002 period and finds that this is generally the case. It's not that divided government is the same as unified government, but either way entrepreneurs in congress and in the executive branch have found ways to pass lots of important laws across the partisan divide.

Jackie Calmes writes in the New York Times, however, that she thinks it's unlikely a new GOP majority in the House of Representatives would lead to a bipartisan coalition for deficit reduction. She paints this picture in fairly broad terms whereby "incumbents otherwise inclined to make deals are now wary, Republicans say privately, mindful of colleagues who lost primary challenges from Tea Party candidates."

I think we should assume that Calmes is right, but I would put forward another hypothesis about this. There's unlikely to be a bipartisan deficit reduction deal because conservatives don't care about the deficit. Dealmaking is possible when people from both sides care about aspects of an issue. No Child Left Behind, for example, appealed to key Democrats like Ted Kennedy and George Miller who thought it was an important tool for focusing educational resources on poor kids and minorities. Many conservatives liked the fact that teacher's unions didn't like it. Bipartisan appeal = bipartisan legislative outcome. Similarly, there's strong support in both parties for a "don't let major banks collapse" agenda, so the Fannie/Freddie nationalization and TARP got done even under difficult circumstances for cooperation.

But conservatives don't favor deficit reduction. They favor tax cuts. When the budget was in surplus, both George W. Bush and Alan Greenspan defined the existence of the surplus as a problem for public policy—one that should be solved with tax cuts. You can't compromise without some element of common purpose.

Cheap Finnish Health Care Is Built on the Back of Low-Paid Doctors

Kevin Drum and Bob Somerby are annoyed that journalists talk about the strong performance of Finland's school system but don't mention its highly efficient health care system. Specifically, the US spends $7,285 per year to Finland's $2,900:

Finland's test scores let a bunch of know-nothing journos push a preferred press corps narrative: Our public schools are a mess! (Maybe we need to privatize! It's all the fault of the unions!) Finland faces none of the daunting educational challenges we face, of course. But so what! All pundits on deck!

By way of contrast, the press corps' deference to corporate interests seems to make it shy from the topic of health care spending. Does Finland achieve good health care at a very low price? This topic can't be discussed!

I dunno, when I went to Finland to learn about their school system I came away writing, among other things, about their highly cost-effective health care system and their health-enhancing school lunch initiatives. To be honest, in my experience something like 97% of commentary on Finnish education involves taking note of their generous and effective Nordic welfare state, so I feel like Drum and Somerby are mostly being cranky here.

But rather than counter-crank, let's ask the question why is it that Finland is able to keep its health care spending so low? As best I can tell, it's all pretty standard stuff. One huge factor is that their doctors make way less money $3,177 per month to $8,189 per month in the United States. They have pharmaceutical price controls. And according to a Harvard Business School analysis (PDF) "Within the municipal health care system, patients have had very limited freedom to choose their health care providers or physicians." Specifically "There is great variability across municipalities in terms of patients' ability to choose their primary care physicians" and for specialists:

A referral from a licensed physician is needed to access municipal specialized care (i.e. hospitals), and patients cannot usually choose their hospital or specialists. Instead, health centres have guidelines listing the providers to which patients with certain symptoms and diagnoses should be referred. Normally, patients are treated in a hospital within their hospital district of residence, and their freedom to choose their physicians within the hospital depends on factors including the organization of departments and the number of specialists.

This all seems to me to work well-enough. At a minium, it's cheap! But who here thinks that running on a platform of drastic cuts in medical professionals' salaries combined with restricted provider choice and large-scale government rationing is going to be a big winner? There's more than "corporate interests" at issue here. Among other things, as long as doctors are about a million times more trusted by the population than are politicians, it's going to be extremely difficult for politicians to ever enact measures that reduce doctors' incomes. But it's extremely difficult to imagine how a more efficient health care system could avoid reducing doctors' incomes.

October 25, 2010

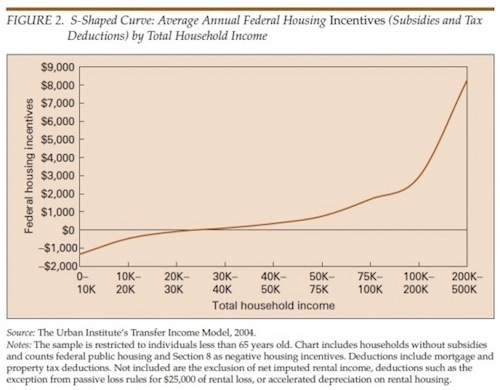

Incidence of Federal Housing Subsidies

The large-scale subsidies to the housing sector is one of the least market-oriented aspects of the American economy, and as Mike Konczal observes they're also hugely regressive, making it unlikely that the politicians who like to rant and rave about free markets will actually do anything about it:

Ridiculous. Phasing out the home mortgage interest tax deduction would be one of the very best measures we could take to reduce the long-term deficit.

Endgame

You should know better:

— Latinos < href="http://www.prospect.org/csnc/blogs/ad... more enthusiastic about voting.

— "The Finnish Health Care System: A Value-Based Perspective" (PDF).

— Web journalism needs workable price discrimination system.

— Physician salaries around the world.

— Government should publish monthly GDP data.

AOL thinks "California Gurls" is the best song of 2010 whereas in fact it's not even the best Snoop Dogg / pop collaboration of 2010. Check out Robyn, <div class=">

Parking Reform in Greater Boston

(cc photo by gracefamily)

A number of readers have sent me Paul McMorrow's article about parking reform in the Boston area and I'm glad you did:

When Boston development officials recently handed permits to the developers of Waterside Place, they did so despite neighborhood concerns that the developers wanted to build far more apartments than parking spots. On A Street, the Boston Redevelopment Authority is close to green-lighting a 21-story residential tower. The tower's developer had originally planned to build one parking spot for every two residential units, an abnormally low supply; BRA officials are pushing the developer to push that ratio even lower by replacing a whole floor of parking with innovative workforce housing units.

These permitting decisions are not happening in a vacuum. Government-imposed floors on the number of parking spots required at new developments are falling across the city, and beyond. Somerville, for instance, is increasing zoning density and lowering parking requirements along the route of the planned Green Line extension, with an eye toward spurring new transit-oriented development. But the change is especially pronounced in the Seaport, where developers are working with as close to a blank canvas as you'll find in any major American city.

Regulators pushing developers to build less parking than they want is much, much, much better than the near-universal practice of regulators mandating minimum levels of parking. But I do think the message is clearer and the potential political coalition bigger if parking reformers just stick to the idea that this should be left up to the market. Cars are useful, and people who have cars need to park them. So there's nothing wrong with building parking. But urban space is expensive, and parking spaces take up space, so people should weigh the costs and benefits of building/buying more parking against other possibilities. Getting to market-determined levels of parking construction and parking space pricing would be a huge victory, and it's not particularly necessary to go beyond that.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers