Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2519

October 25, 2010

TARP and Commercial Paper

Dean Baker denounces the "hoary lie" that TARP was needed to prevent the collapse of the commercial paper market, arguing:

Bernanke was deceiving Congress with his discussion of the commercial paper market because he single handedly possessed the ability to support the commercial paper market. In fact, the weekend after Congress voted for the TARP he announced that he would create a special Fed lending facility to directly buy commercial paper from non-financial companies.

If Bernanke had been honest with Congress he could have told them of his plans to create such a facility before they voted on TARP and explained that the commercial paper market could be sustained whether or not they approved the TARP bailout.

This is worth mentioning now because this hoary lie keeps popping up. Let's be clear, it was important for the Fed/government to take steps to sustain a working financial system. But these steps could have included conditions that made Wall Street pay a huge price and change its mode of operation forever.

The "keeps popping up" link is to my post from this morning on the money-money market run and I don't really see that Baker and I disagree. To quote myself:

It would be silly to say that the policies adopted in response to this—TARP and the AIG bailout, primarily—were the only possible responses. But absent some kind of (nominally) costly and unpopular bailout we would have had a costly and unpopular sequence in which people's "safe" money market accounts were wiped out, to say nothing of perfectly solvent firms being suddenly unable to meet payroll.

So I say: We didn't need to follow the Paulson/Bernanke/Geithner script precisely, but we did have to take some kind of dramatic and unusual action. Baker says that we did have to take some kind of dramatic and unusual action, but we didn't need to follow the Paulson/Bernanke/Geithner script. I don't see these as particularly divergent points of view, but it is worth understanding the issue from both perspectives. Back in the winter of 2008-2009 I thought Baker's point was the most important one, but from the perspective of the fall of 2010 I think the bigger problem is that a growing number of people have persuaded themselves that there was never any kind of real problem here.

Is It Hard to Inflate?

Reading Paul Krugman's post today on I "Sam, Janet, and Fiscal Policy" I get the sense that he thinks it would be difficult for willing policymakers to create temporarily elevated inflation expectations.

To me, it seems like this would be easy. Note, for example, that increased Fed chatter about quantitative easing seems to have successfully reversed a downward trend in the TIPS spread:

When considering the whole issue, I think a lot of economists tend to underrate the potency of the "communications channel," perhaps because it's hard to model. But I think that if Ben Bernanke announces a new round of quantitative easing after the election and comes out and says "I'm doing this QE because I want to raise the price level and I'll do more if it doesn't go up fast enough" that the impact will be enormous. By contrast, if he keeps assuring people that he doesn't want to see inflation peak over 2% under any circumstances, then recovery will be restrained.

This is, I freely concede, very much a media person's way of looking at things rather than an economist's. But in economic terms, a lot of financial markets activity has the qualities of a Keynesian beauty contest and clear communications guidance from policymakers can shift the coordination point. Then those financial activities have an impact on real activity.

How Much Racial Displacement Really Happens?

I used to live in DC's U Street neighborhood and was fascinated by the local history. Essentially it was a key commercial main street for the city's black community during the Jim Crow era, then fell apart under the triple pressures of riots, desegregation, and urban disinvestment and then has been reinvented since the opening of the U Street Metro station as a substantially whiter neighborhood. Lydia DePillis' profile of Sandra Butler-Truesdale ads a lot to my understanding and also prompted some further research with this remark:

Butler-Truesdale has a multifaceted take on gentrification. On the one hand, she mourns the loss of African American cultural dominance on U Street. When developer Chris Donatelli—whom she calls "my good friend"—built the Ellington apartments, she asked him whether anybody who looked like the building's namesake would be able to live there. At the same time, however, she doesn't blame white people for black displacement.

"People say a lot of stuff, and half the time they don't really know what's happening," she says. "You have to look at the fact that most of this is about the economy. It's about the fact that we live in these neighborhoods and did not actually buy property…When you do that, you have no real anchor, and people can do what they want to do to you."

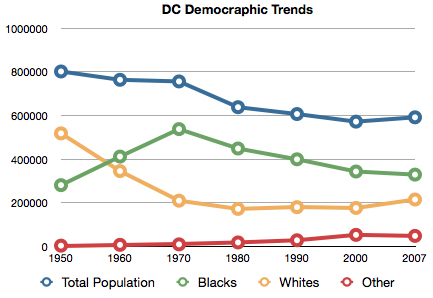

You certainly do see a lot of displacement on a micro level. But I wonder on a bigger scale how much racial displacement really happens. Here's some DC demographic trends:

It seems to me that by far the largest degree of black population decline happened during the 1970-2000 era when the white population was slowly falling from an already low level. It's true that the 2000-2007 period saw a small increase in the white population and a small further decline in the black population, but this "displacement" phase looks like a tiny blip in the scheme of things. The 2007 white population is about even with the 1970 white population, but the city contains about 100,000 fewer African-Americans than it did then. Those people aren't gone because anyone displaced them. I assume they're gone largely because declining housing discrimination made it much more possible for black people to move to the suburbs.

At any rate, the striking fact about DC is that, like many older American cities, it has many fewer residents in 2010 than it had 50 or 60 years ago even though the overall population of the country has increased dramatically. Given appropriate policies, there should be plenty of room for large net increases in population and not just displacement. But that requires continued investments in transit infrastructure and updated zoning codes that allow developers to build high density structures and no more parking than the market demands.

A Call for Judgment

Over the weekend at the behest of Reihan Salam and Steve Teles, I read Amar Bhidé's A Call for Judgment: Sensible Finance for a Dynamic Economy. From a progressive perspective, this is a sort of odd book. You basically get an argument familiar to the left—wiz-band modern finance isn't actually useful, largely constitutes the shifting around of rents, and is based on gambling with taxpayer guarantees—but wrapped up in lots and lots and lots of conservative-sounding rhetoric. A liberal might make this argument with some reference to the misfortunes of workers or poor people, Bhidé instead worries that the backlash against super-rich princes of Wall Street may lead to unfair castigation of the super-rich princes of the real economy. The name "Hayek" appears over and over and over again as if repeating this incantation will trick you into not noticing that the substantive proposal at the end is for a revival of heavy-handed midcentury regulation of the financial industry.

The main prescription is essentially a new version of Glass-Steagall with the default switched around in order to make it more secure against erosion. Insured depository institutions will be given a menu of permitted functions and told they're not allowed to do anything else. Bhidé then proves his conservative bona fides by pairing this populist suggestion with the idea that financial firms outside this sphere of guarantees should be completely deregulated, which presumably will be paired with the Ben Bernanke swearing a "cross my heart and hope to die" oath not to undertake any future bailouts.

The goal of all this is to accept that certain kinds of bubbles and manias are inevitable, but to seek to ensure that future ones play out more like the dot-com bubble rather than the deleveraging cascade of 2007-2008. The model banker is either the old-school mortgage lender who's really asking is this guy going to pay back his debts or else the new-school venture capitalist who's moving capital into the hands of specific entrepreneurs he has some faith in. The theme here is that the only risk-management strategy that really works is judgment and research not quantitative hedging models that Bidhé deems inherently unworkable for Taleb-like reasons.

At any rate, even though I thought the ideological self-positioning of the author got a bit annoying I do think everyone should read this book. For one thing, though Bhidé doesn't seem super-interested in pursuing this line of inquiry, I think that if it's correct it fills in the microfoundations missing from the argument of Hacker and Pierson's Winner-Take-All Politics by producing a plausible account of how developments in the financial sector could produce both super-inequality and middle class stagnation through the misallocation of resources away from real economy innovators.

As with many of the better post-crisis books, I wish a bit less time had been spent on the author's backward-looking narrative and a bit more on considering counterarguments and possible problems with his proposal. Can the government credibly withdraw guarantees from the non-bank financial sector? Isn't this especially problematic in a political system where large legislative reforms are inevitably incremental? If it can, will the result be distorting misallocation of capital into those few fields that the newly restricted guaranteed banks are allowed to invest in? Will this proposal merely shift shady behavior into other countries while still leaving the US vulnerable to systemic risk shocks? I don't think these are knock-down objections but they're not totally trivial either.

Psychological Foundations of Political Belief

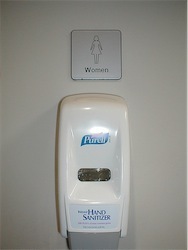

(cc photo by moira)

The political science literature about what drives election outcomes is kind of at odds with the conventional wisdom among campaign operatives and reporters. But the emerging research on the psychological foundations of individual political belief is downright weird. Peter Liberman and David Pizarro, for example, have a good piece in the NYT about the link between disgust and conservatism:

Subtle cues about disgust and cleanliness can affect social and political judgments as well. In an experiment conducted recently by Erik Helzer, a Cornell Ph.D. student, and one of us (David Pizarro), merely standing near a hand-sanitizing dispenser led people to report more conservative political beliefs. Participants who were randomly positioned in front of a hand sanitizer gave more conservative responses to a survey about their moral, social and fiscal attitudes than those individuals assigned to complete the questionnaire at the other end of the hallway.

In another experiment one of us (Dr. Pizarro) was involved in, a foul ambient smell — emitted, unbeknownst to test subjects, by a novelty spray — caused people answering a questionnaire to report more negative attitudes toward gay men than did people who responded in the absence of the stench. Apparently, the slightest signal that germs might be present is enough to shift political attitudes toward the right.

I think it remains to be seen how these kind of dynamics play into macro-scale political phenomena, but suffice it to say that people aren't making up their minds about political issues based purely on judicious consideration of the evidence.

Iranian Bribes? They Gonna Come Talk to Me About Iranian Bribes? In Afghanistan?

Hamid Karzai responds to allegations that his chief of staff is the beneficiary of large Iranian bribes:

Afghan President Hamid Karzai said Monday that once or twice a year Iran gives his office $700,000 to $975,000 for official presidential expenses – and that Washington also provides "bags of money" because his office lacks funds. Karzai's comments come a day after The New York Times reported that Iran was giving bags of cash to the Afghan president's chief of staff, Umar Daudzai, to buy his loyalty and promote Iranian interests in Afghanistan.

On a serious note, Iran and Afghanistan are adjacent to one another and a large number of Afghans—including Hamid Karzai—speak a version of the Persian language. The United States and Iran have a decades-long grudge match mostly over events that transpired in the Carter and Eisenhower administrations. It would be exceptionally foolish for the government of Afghanistan to deal with Teheran primarily through the lens of that dispute.

The Next Boom

Patrick Doherty and Christopher Leinberger have a great piece in the Washington Monthly about the potentially bright future for walkable urban real estate development. They observe that population growth plus the declining proportion of Americans who have kids at home plus shifting preferences among young people (driven in part by declining crime rates, etc.) are creating a boom in demand for walkable transit-accessible neighborhoods:

Ten years ago, the highest property values per square foot in the Washington, D.C., metro area were in car-dependent suburbs like Great Falls, Virginia. Today, walkable city neighborhoods like Dupont Circle command the highest per-square-foot prices, followed by dense suburban neighborhoods near subway stops in places like Bethesda, Maryland, and Arlington, Virginia. Similarly, in Denver, property values in the high-end car-dependent suburb of Highland Ranch are now lower than those in the redeveloped LoDo neighborhood near downtown. These trend lines have been evident in many cities for a number of years; at some point during the last decade, the lines crossed. The last time the lines crossed was in the 1960s—and they were heading the opposite direction.

In principle, these shifts in demand should lead to a large quantity of economic activity in the field of "retrofitting" existing neighborhoods with more robust transit links and more intensive development. But:

Today, even though consumer preferences have changed, most of the old rules and subsidies remain in place. For instance, federal transportation funding formulas, combined with the old-school thinking of many state departments of transportation, continue to favor the building of new roads and widening of highways—infrastructure that supports low-density, car-dependent development—over public transit systems that are the foundation for most compact, walkable neighborhoods. When developers do propose to build denser projects, with narrower streets and apartments above retail space, they often run up against zoning codes that make such building illegal. Consequently, few compact, walkable neighborhoods have been built relative to demand, and real estate prices in them have often been bid up to astronomical heights. This gives the impression that such neighborhoods are only popular with the affluent, when in fact millions of middle-class Americans would likely jump at the opportunity to live in them.

As an analyst of public policy issues, I certainly hope this turns around and anyone who reads this blog will know I'm doing my best to persuade people to rethink this. As a condo owner in a very new building in a newly developing dense walkable neighborhood (as in it was literally vacant lots, rather than a classic gentrification scenario) who reads his building email list, I'm a bit skeptical that change is going to happen. Even people who are eager to move to denser urban neighborhoods are almost shockingly hostile to the idea of anything in the existing neighborhood being redeveloped in a denser way. So it seems to me that any change that happens, if it does happen, will have to take place on a longer time horizon than Doherty and Leinberger seem to have in mind since there's a lot of persuasion work that has to be done.

But speaking of persuasion, Leinberger's short book The Option of Urbanism: Investing in a New American Dream did a lot to change my thinking about this topic and it's highly recommended.

Bloggers Are People Too!

Chopped liver (cc photo by peretzpup)

Writing about Bravo's Millionaire Matchmaker, Amanda Fortini and the NYT manage to pull the classic MSM stunt of quoting a blogger without naming her:

Last April's finale garnered a series high of almost 1.6 million viewers. Even those who generally consider themselves too refined for reality TV — the microwave dinner of the entertainment world — are closet fans. "Watching Patti rather savagely describe what's wrong with these guys and why they have trouble getting/keeping themselves in real relationships is strangely invigorating," wrote a blogger for the feminist magazine Bitch before fretting: "Can I continue to watch this show and write for Bitch in good conscience?"

I put the quote into Google, and swiftly unearthed the post in question by Anna Breshears. Would it be so hard to use her name? To include a link to her post in the online version of the article?

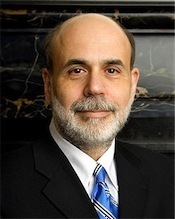

Does Ben Bernanke Secretly Want Fiscal Expansion?

Don't get me wrong, I liked this Alan Blinder column qua economic policy commentary, but I don't find his mind-reading speculations very plausible:

The two main thoughts that are probably going through Mr. Bernanke's head today are, first, "I sure wish I could get some help from fiscal policy," and second, "I probably can't, so I'd better do whatever I can." He's right on both counts.

The Fed Chairman's not locked up in the Tower of London. He's not mute. He's not even unwilling to comment on fiscal issues. But when he gave a big speech on fiscal policy on October 4, he focused entirely on the need for long-term deficit reductions. And I agree with him that such reductions are desirable. But I also think, just like Alan Blinder, that in the short term a bigger deficit would be helpful. If Bernanke wanted to say that, he had a great opportunity. But he didn't. Presumably for the same reason that he's consistently acted like a conservative Republican in other regards over the past two years—he's a conservative Republican.

I think people tend to overestimate the number of mistakes Barack Obama has made in his presidency. But the flipside of that is that they underestimate the severity of the mistakes that are real. Giving the most important economic policy job in the country to someone who doesn't share his values, ideology, and partisan loyalty was a big big big mistake and it's reflected in Bernanke's conduct around questions like this one.

The Money Market Run

Something that's been bugging me for a while now is that people largely seem to have forgotten what it is that actually happened in the fall of 2008 as the financial crisis reached its most acute stage. Amar Bhidé's new book, A Call for Judgment: Sensible Finance for a Dynamic Economy, isn't primarily a history of this episode but it does contain a handy one-paragraph summary of why it is that the powers that be didn't just let things fall apart:

The common wisdom was that money market funds were "unrunnable," because all withdrawals (redemptions) could be met by selling the assets of the fund. The illusion was shattered in September 2008. The pioneering Reserve Fund had large holdings of commercial paper issued by Lehman Brothers; the failure of Lehman triggered redemption requests for more than $20 billion on September 15, but less than half could be honored by selling assets since the markets were frozen. By the end of the next day, more than $40 billion of redemption requests were received. On the seventeenth, redemption requests were surging at all money market funds, but the funds were unable to sell any but their safest and shortest term securities. The commercial paper market froze and with it the capacity of issuers—both financial institutions and industrial companies—to raise the funds needed for day-to-day functioning.

It would be silly to say that the policies adopted in response to this—TARP and the AIG bailout, primarily—were the only possible responses. But absent some kind of (nominally) costly and unpopular bailout we would have had a costly and unpopular sequence in which people's "safe" money market accounts were wiped out, to say nothing of perfectly solvent firms being suddenly unable to meet payroll.

And the problem here was quite abstract and general. We had all these accounts that households and firms were treating like super-safe unrunnable deposits when they were, in fact, vulnerable to runs. The specific incident was touched off by Lehman Brothers' bankruptcy which, in turn, was driven by housing bubble issues but even had that whole episode been avoided the vulnerability was still lurking there.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers