Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2516

October 28, 2010

Peter Orszag's Odd QE2 Reasoning

I've been wondering for a while who it is on the White House economic time who failed to mention to Barack Obama that expansionary monetary policy is a crucial part of the recovery mix. Surely not Christina Romer ("A second key lesson from the 1930s is that monetary expansion can help to heal an economy even when interest rates are near zero" ["PDF"). But was the villain Peter Orszag? He has an item up at the NYT blog today arguing that additional quantitative easing might actually hurt the economy.

He builds the argument initially by citing Paul Krugman's skepticism about QE2 while failing to note Krugman's belief that monetary policy could work if the Fed was sufficiently determined about it. But he then pivots to a truly strange political economy argument:

Ironically, QE2 could make the right policy mix less likely. In particular, any substantial additional stimulus will probably not (and should not) be enacted without a medium-term deficit reduction package — and that medium-term deficit reduction package is less likely to be enacted when interest rates on long-term government bonds are so low.

In other words, by perpetuating an artificially low 10-year government bond rate, the Fed may be delaying (even if very modestly, given the modest impact of the action on long rates) the very fiscal policy action that the nation most needs, while doing little to boost an economy whose principal problem is not high long-term interest rates.

His view, in other words, is that the road to recovery starts with a spark in long-term interest rates. This is bad for the economy, but it leads to a renewed outburst of deficit panic. That panic leads to congressional support for long-term fiscal austerity. That, in turn, leads to increased congressional support (but how?) for short-term fiscal expansion. But if the Fed acts to hold interest rates down, then none of this will happen, and let's just not pay attention to the fact that lower long-term interest rates might spur investment and growth.

In addition to being an implausible model of how congress works, I think this gets the interplay between fiscal and monetary matters backwards. The legitimate concern you would have with deficit-increasing stimulus is that it would "crowd out" private investment via higher interest rates. Commitment by the monetary authorities to not let them happen is necessary for fiscal policy to work.

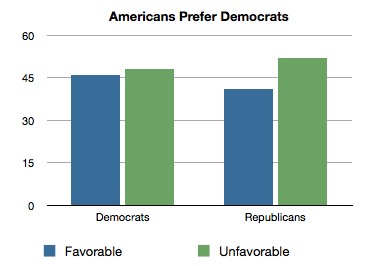

Americans Prefer Democrats, Are Planning to Vote Republican

It seems to me there are two kinds of things you can ask for in a pre-midterm poll. One is a predictive gauge of how people are likely to vote, and one is an interpretative gauge of what their overall view is. And on the predictive point the latest NYT poll is loud and clear that the GOP is positioned to win big. But in interpretive terms, I'm struck by how little weight journalists keep giving to the numbers on overall attitudes toward the parties, because the result—they prefer Democrats—is pretty consistent:

You can give this a number of interpretations. One would cite it as evidence of irrationality. Another would be to cite it as evidence that even though voters prefer Democrats all things considered, they don't love Democrats so they like the idea of restraining Barack Obama's ambitions. Either way, it doesn't change the fact that the odds strongly favor big Republican gains. But in terms of looking further forward at the future it re-enforces my point about the banality of tea—if hard-right conservative politics were suddenly poised for a comeback, the Democratic Party wouldn't be the more popular of the two major parties. Similarly, President Obama himself at 45-47 is in a vulnerable posture but considerably more popular than the opposition party. At a minimum, anyone who thinks such a comeback is around the corner owes the world an explanation of these anomalous polling results.

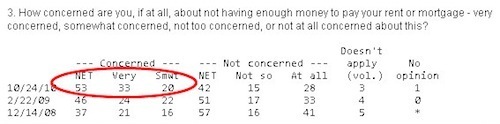

The Worry Baseline

Kevin Drum and Joe Klein blog about a Washington Post poll question on how worried people are about making their mortgage payments:

I find data like this almost impossible to interpret. What's the baseline? Back in 2005 when the media wasn't interested in housing problems and nobody was polling this issue, how many people would have said they were worried about mortgage payments? How much do people say they're worried about things in general? How much more do people start worrying about their mortgage when you specifically start pestering them about it. I bet most Americans between the ages of 25 and 40, in practice, rarely worry about saving for retirement. But if you ask them about it then they'll start worrying. Right?

October 27, 2010

Endgame

It's a small small world:

— Roger Sterling's fake memoirs to be actually published.

— Everything you ever wanted to know about the consumer financial protection bureau.

— From the archive: EMH rhetoric.

— Even parking garages have a trade association.

— Haitians fed up with incompetent relief efforts.

Tilly and the Wall, "Pot Kettle Black".

Conservatives Don't Care About the Deficit, "Cutgo" Edition

As I've been at pains to argue for a while now, the modern American conservative movement does not care—even a little bit—about the size of the budget deficit. For example, congressional Democrats have a procedural rule in place called "PAYGO" that makes it difficult to reduce revenue or increase expenditure without offsets. A movement that cared a lot about the deficit would be promising to alter this rule so as to reduce loopholes. A movement that cared some about the deficit would be promising to leave it in place.

But as Jon Chait observes, that's not what the GOP is doing, instead they want to scrap PAYGO and "replace it with a different rule, Cutgo, which would require that new spending be offset with spending cuts."

In other words, they want to make it easier to expand the deficit. And note that this doesn't even particularly make it harder to expand the deficit through spending. It just means that your new spending program needs to be called a "refundable tax credit" and administered by the IRS. That means that new government subsidies for things are likely to be handed out in a relatively inefficient way, via the tax code, and the deficit is likely to get bigger. Now you can make the case for these priorities, but it would be nice if the press would wake up and notice what they are.

What Was The Hipster?

Not hipsters, but they live in Williamsburg (cc photo by myshi)

Sometimes it's worth linking to something just because it's a piece of flat-out good writing, and I'll put Mark Grief's essay "What Was The Hipster?" in that file any day of the week.

My favorite graf:

The most confounding element of the hipster is that, because of the geography of the gentrified city and the demography of youth, this "rebel consumer" hipster culture shares space and frequently steals motifs from truly anti-authoritarian youth countercultures. Thus, baby-boomers and preteens tend to look at everyone between them and say: Isn't this hipsterism just youth culture? To which folks age 19 to 29 protest, No, these people are worse. But there is something in this confusion that suggests a window into the hipster's possible mortality.

I don't really have anything to say about this, though I will note in a boring way that what I think is most interesting about the term "hipster" is that it seems to function in a purely relational sense. For any city-dwelling member of my generation, there's always some other set of people who are the "hipsters" and some other set of people who think you're one of the hipsters.

Institutional Design Matters a Lot

(cc photo by steve snodgrass)

This blog doesn't endorse candidates for office, but this Greater Greater Washington endorsements post raised an issue of general applicability:

When Five Guys wanted to open a patio on an empty sidewalk in an area with vacant lots across the street, [incumbent Bob] Siegel opposed the idea unless Five Guys would make a donation to other community initiatives.

GGW sees this as an error of policy analysis:

This exemplifies a common problem with ANC 6D as well as some others around the city, which don't see new retail and sidewalk cafes as a benefit on themselves but demand contributions to other projects in exchange for permission to exist.

I think that's a misdiagnosis. We're seeing an error of institutional design. Advisory Neighborhood Commissions don't have very much power or very much responsibility. But they do have a lot of power over liquor licenses, sidewalk cafes, and zoning variances. ANC members, however, have views on things other than liquor licenses, sidewalk cafes, and zoning variances. So the most reasonable way for them to achieve a diverse set of policy goals is to adopt a very stringent attitude toward liquor licenses and sidewalk cafes, and to support very restrictive zoning rules that increase the value of variances, and then to trade permission to do business for other kinds of favors.

If a fixed portion of retail sales taxes raised in a given ANC were put into a neighborhood fund controlled by the commissioners, then I bet commissioners would suddenly be less interested in swaps of these sorts and more interested in attracting businesses to their area. But instead we've set up ANCs in a way that encourages them to be systematically biased against just saying "yes" to local retailers. What's more the districts are so tiny that people don't think about the systematic consequences of their actions. One itty-bitty neighborhood with 4 eateries instead of five doesn't seem like a huge difference. But a citywide 20 percent "restaurant gap" encourages high prices, mediocre food, needlessly elevated unemployment, etc.

The Banality of Tea

I did a radio interview earlier today about the midterms and something that struck me repeatedly was the totally unwarranted sense many seem to have that a GOP pickup of 55-60 House seats would represent some kind of bold new era of conservatism and/or descent into manic fascism. I'm not very old, and I remember perfectly well life under a House GOP majority in the 1995-2006. They did some good things, they did some bad things, they did some stupid things, and then they lost power. Ta-da. Life goes on.

More generally, over the past 20 years we've had unified Democratic control for four years (1993-94 and 2009-10) and unified GOP control for four years (2003-2006) and divided government for the other twelve. In the twenty years before that divided government was even more common. So a big Republican win will take us from an abnormally strong political position for Democrats back to version of the situation that typically prevails in modern America—one that will probably leave them with less influence over policy than they had in 2007-2008.

I don't want to deny that the change is a big deal. The shift out of the normal situation and into the abnormal one that occurred in November 2008 was a significant event. And it led to, among other things, a sweeping overhaul of the health care sector. So switching back into normal position is also a big deal. But it's a big deal in the sense that things are going back to normal, not in the sense that we're entering a new wild era in which Americans will finally repudiate the welfare state.

Communications Channel

As I've been noting lately, press reports that the Fed is plotting a new round of quantitative easing have been boosting markets and reviving hopes for an economic recovery. Then today the Wall Street Journal published a disturbing story about how Ben Bernanke thinks monetary policy is like golf and he doesn't want to hit too hard.

Action, reaction: "Stocks slid Wednesday as concerns grew over whether the Federal Reserve's plans to buy Treasury bonds might be smaller and slower than anticipated."

This is bad. I think policymakers need to start recognizing the power of communications strategies over the economy under these circumstances. One important reason that changes in nominal interest rates traditionally had a lot of sway over the economy is that they spoke in a well-understood language. Rate cut means "Fed is boosting growth" while rate hike means "Fed is fighting inflation." With nominal rates at zero, this traditional language has fallen apart. But communication still works. The Fed should say that it's ready, willing, and able to do what it takes to boost the price level and that its actions—whether gradual or not—should be read in that light.

The Road to Additional Stimulus

David Leonhardt says Democrats lost their sense of urgency on economic recovery too soon. Jon Chait responds that " I just don't see many ways the political system, with its extreme partisanship and routine filibustering, could have accomodated more fiscal stimulus."

Fortunately, my TAP Online column today addresses this:

Marketing and public relations are nice, but opinion is fundamentally driven by results. And on this, Obama has it backward. A party whose leaders realized that economic results were the most important driver of public opinion wouldn't have renominated a conservative Republican to head the Federal Reserve. Even more astoundingly, having given Ben Bernanke a second term in office, the Obama administration didn't get around to nominating anyone to fill the other vacant posts on the Federal Reserve Board until April 2010. Then, once the nominations were made, Senate Democrats didn't speed the hearings and confirmation process along. One of Obama's nominees, Peter Diamond, actually managed to win a Nobel Prize in economics while still languishing in confirmation limbo.

Similarly, the extent of stimulus possible in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act was famously limited by the need to gain Republican support. Given that, shouldn't someone have put reconciliation instructions into the budget resolution that would have allowed for additional stimulus to be undertaken by majority vote? Instead, Senate Democrats wound up spending much of 2010 in painstaking negotiations with a handful of New England Republicans, desperately trying to eke out a few more dollars.

A lot of liberals seem to prefer a quantity-based approach to second-guessing the Obama administration's decisions. In this telling, the gang in the White House are history's greatest monsters and they've been doing everything wrong. I disagree. I think they've mostly been making the right calls. But that's not to say they haven't made mistakes. Instead it's to say that the mistakes they have made were a lot bigger than people generally realize.

Now to be clear, Democrats would be losing huge numbers of House seats under any plausible scenario. But the Harry Reids and Alexei Gianoulises and Russ Feingolds of the world could be in much better shape if a couple of things had been done differently.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers