Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2512

November 1, 2010

Doing My Part to Boost Voter Apathy

Will Wilkinson says , via a broader argument which says that elections in general don't matter as much as people say. Ross Douthat says he doesn't agree with all of it but that "it's still a useful corrective to the vast effort currently underway to persuade you that this election (like the election before it, and the election before that) is a world-historical hinge moment, and that nothing in American life matters more than how many seats the Republicans gain or don't gain next Tuesday."

I agree with both of them, but that still leaves open the question of how important is the election compared to other elections. The 2008 elections led, after all, to a very important piece of health care legislation that's not going to be repealed during the 112th congress. In other words, even after the soon-to-come revival of conservative political fortunes the health policy status quo is going to settle well to the left of where it was before the election. And it seems overwhelmingly likely to me that had Kay Hagan and Al Franken not won their close elections in North Carolina and Minnesota that the Affordable Care Act never would have passed. So as far as elections go, that's a pretty big deal.

By contrast, looking ahead even if the Democrats defy expectations and eke out a narrow House majority they're not going to turn around and pass a cap-and-trade bill. And if Republicans defy expectations and pick up 65 House seats instead of 55 House seats, that's not going to conjure up the votes to scrap the minimum wage. In any remotely plausible range of outcomes, we'll be looking at an era where either nothing happens or else compromises are reached between the party leaders. The precise numbers matter of course, but they don't matter nearly as much as they did in the current congress where a couple Democratic "reach" wins in Senate elections transformed the situation.

Is It Hard to Create Inflation Expectations?

Paul Krugman says he "very much agree[s] with the notion that central banks can gain traction, even in a liquidity trap, if they can credibly promise future inflation — that was the whole moral of my 1998 paper."

That paper is the lynchpin of my understanding of this issue as well, but Krugman seems very skeptical in practice that monetary action will deliver the goods:

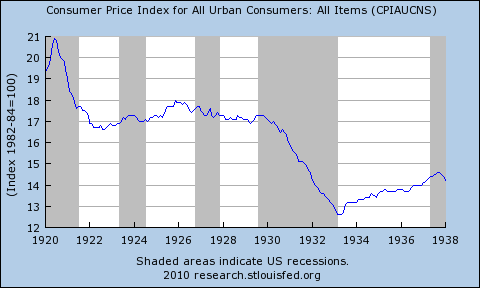

But in the 30s, we were mainly talking about ending expectations of deflation, or at most creating expectations of a rise in the price level to where it was before the Depression; remember that even in 1938, prices were well below 1929 levels:

That's very different from trying to create expectations of inflation looking forward with no actual deflation in our past.

It's certainly different. But is it "very" different? It doesn't seem all that different to me. Suppose the official Fed statement after the next meeting involves some QE and gives as the reason for it "the inflation rate is too low, we believe this round of QE will produce extra inflation and if it doesn't we're going to do more QE." That would certainly lead me to expect more inflation.

It seems to me that the problem we face is much more that the median member of the FOMC is unlikely to agree to such a strong statement than that a strong statement wouldn't work.

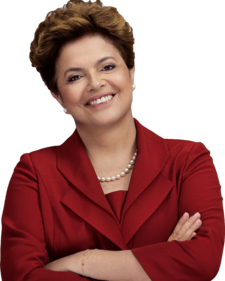

The Woman Behind the Man Behind the Woman

Having secured election as the first woman president in the history of Brazil, Dilma Rousseff said she wants "fathers and mothers to look their daughters in the eyes and say, 'Yes, a woman can.'"

Irin Carmon is a bit dubious:

Perhaps it would be more accurate in this case to say, "She can, with the most powerful man in Brazil backing her," in this case term-limited president Lula, for whom Rousseff served as chief of staff and energy minister. Just about every man/woman on the street interview yielded a mention that the voter hoped it would mean another term for the wildly popular Lula. (In the AP: "If Lula ran for president 10 times, I would vote for him 10 times…I'm voting for Dilma, of course, but the truth is it will still be Lula who will lead us.") Rousseff has never run for office and just about every story about her refers to her lack of charisma, despite a dramatic past as a guerrilla fighting Brazil's dictatorship.

I think this is a bit unfair to Rousseff and her very real achievement. Successions of this sort in which a popular term-limited leader tries to hand power off to a less-charismatic subordinate happen in politics all the time. Think of Ronald Reagan and George HW Bush or Bill Clinton and Al Gore. And the point in all cases is that attaining the status of "heir apparent to hugely successful politician" is itself a pretty impressive achievement. Here in the United States, after all, the appointment of a woman chief of staff would be something of a milestone all its own. Nobody gets ahead in politics without patrons, and Rousseff is no exception, but she had a very substantive role in Lula's administration and there's no reason not to point to her accomplishments in the general spirit of "yes, a woman can do it."

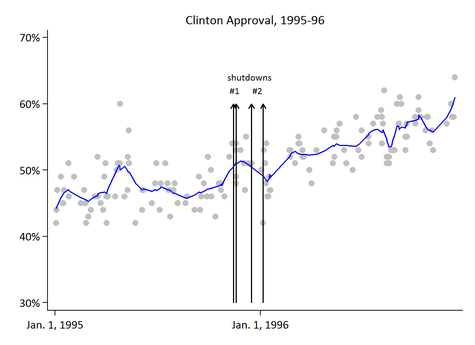

Did the 1995 Government Shutdown Boost Public Approval of Bill Clinton?

Conventional wisdom in Washington DC is that the "government shutdown" prompted by then-Speaker Newt Gingrich's hardball tactics was a political fiasco for congressional Republicans. And today conventional wisdom is split between a camp that thinks conservatives have "learned the lesson" of this fight and won't do it again, and those who think that Tea-fueled House backbenchers will force a shutdown.

John Sides suggests that the conventional history is a bit simplistic:

There are perhaps other ways we can score the government shutdown. As I noted, other public opinion data suggested that more people faulted Gingrich than Clinton. And clearly Gingrich blinked first. Clinton "won" in that sense.

But the public did not come to feel more favorably toward Clinton during this period, which suggests again that life under divided government isn't easy, even when presidents fight the opposite party and win.

Of course economic conditions also promise to be quite different in 2011 than they were in 1995. My sense is that under current conditions, a temporary halt in government purchases and transfers would be not only annoying to people but potentially really harmful to the larger macroeconomic picture.

When Drugs Are Outlawed, Only Outlaws Will Sell Drugs (By Definition)

(cc photo by Greg Hayter)

Mark Kleiman notes an awful lot of dubious arguments in the new document (PDF) from the Drug Enforcement Administration and the International Association of Chiefs of Police. Here's my (least) favorite, from their argument that legalized drugs wouldn't reduce the level of violence and disorder in Mexico:

Criminals won't stop being criminals if we make drugs legal. Individuals who have chosen to pursue a life of crime and violence aren't likely to change course, get legitimate jobs, and become honest, tax-paying citizens just because we legalize drugs. The individuals and organizations that smuggle drugs don't do so because they enjoy the challenge of "making a sale." They sell drugs because that's what makes them the most money.

The final sentence here is insightful. The rest is ridiculous. People sell drugs to make money. They don't sell drugs because they've "chosen to pursue a life of crime," they're trying to pursue a life of money-making. They're criminals because the thing they're trying to do to make money is illegal. If it were legal for them to sell drugs they'd be thrilled! But they wouldn't be criminals. This seems perfectly obvious. If drugs were legal, it'd be like cigarettes or beer—sold on the retail level by regular retailers, and produced and wholesaled by large multinational corporations that lobby for light taxation and engage in large scale advertising to grow market share. Like all vendors of addictive substances, whether legal or illegal, they'd depend for their profits largely on growing the population of addicts and this would have bad public health consequences. But like most businessmen, they'd shy away from settling disputes via armed battles.

Is anyone really fooled by denying this? I'm not eager to see fully commercialized heroin sold at the corner store, but turning drug distribution into a serious criminal act has very clearly served to create a largish economic sector full of serious criminals.

Military-Industrial Complex Policy

Ezra Klein says that while bombing Iran may not be the road to recovery, defense spending can be an important driver for public investment:

Since it's unpalatable to simply subsidize certain industries or marshal hundreds of billions for certain investments, but it's indisputable that you need to give the military anything it asks for, you have the military decide every tank needs to run off solar panels, or, to use an even more unlikely example, that we need a national highway system "to allow for mass evacuation of cities in the event of a nuclear attack." You could imagine both infrastructure investments and energy independence fitting the bill today. Then you get your stimulus but you don't need to have your war.

The Internet, of course, has its origins in the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency rather then the Large Scale Investments in Communications Infrastructure Agency.

But I also think this is a bit of a self-limited process. To the extent that everyone presses their policy priorities in terms of defense-related rhetoric, the social and political prestige of the military is further enhanced. And to the extent that the military establishment's social and political prestige goes up, the Pentagon's leadership is better able to direct defense-related industrial policies toward its own objectives rather than to civilian ones operating under cover of national security. And I think that's where we are today. The Brazilian military may be "placing some big orders for advanced aircraft because it would help them build a domestic airplane-manufacturing industry" but the American military is investing in robots because it genuinely wants to use automated systems to fight wars. The result in their case is a strategic investment that may or may not pay off over the long term. The result in our case is to divert scarce engineering talent away from civilian robotics applications that could be much more broadly beneficial.

Immigration is Good for America

Tyler Cowen makes the case for immigrants in his New York Times column:

We see the job-creating benefits of trade and immigration every day, even if we don't always recognize them. As other papers by Professor Peri have shown, low-skilled immigrants usually fill gaps in American labor markets and generally enhance domestic business prospects rather than destroy jobs; this occurs because of an important phenomenon, the presence of what are known as "complementary" workers, namely those who add value to the work of others. An immigrant will often take a job as a construction worker, a drywall installer or a taxi driver, for example, while a native-born worker may end up being promoted to supervisor. And as immigrants succeed here, they help the United States develop strong business and social networks with the rest of the world, making it easier for us to do business with India, Brazil and most other countries, again creating more jobs. [...]

The current skepticism has deadlocked prospects for immigration reform, even though no one is particularly happy with the status quo. Against that trend, we should be looking to immigration as a creative force in our economic favor. Allowing in more immigrants, skilled and unskilled, wouldn't just create jobs. It could increase tax revenue, help finance Social Security, bring new home buyers and improve the business environment.

When a new person joins the economy, you have both complement effects and competition effects. People's thinking tends to be dominated by the competition effect, but people should be pushed to think harder about this. For the competition effect to dominate an immigrant's impact on your life, then his or her skill-set needs to be very similar to yours. If you're a Spanish-speaking construction worker with very poor English, then the entry of an additional Spanish-speaking construction worker with very poor English is probably bad for you. And, again, when a new Ethiopian cook comes to DC that's mostly competition for existing Ethiopian cooks.

Which is just to say that the people who primarily suffer from competition with immigrants are other immigrants and in the real world this isn't where the center of gravity of anti-immigration politics is. So while I do think it's important to keep pressing these economic arguments, I also think it's important to keep in mind that they really aren't the core of the concerns people have about immigration. And I don't say that simply to dismiss those concerns—the practical gains from more immigration would be gigantic, so it's worth confronting and addressing what bothers people as well as pushing back on the fallacies of anti-foreigner economics.

The Small Downsides of Monetary Action

Neil Irwin generally offers the best insights into what the Federal Reserve staff is thinking, so his account of the potential downsides of monetary action is worth taking seriously:

But should the Fed overshoot in its plan to pump hundreds of billions of dollars into the economy, it could produce the same kind of bubbles in the housing and stock markets that caused the slowdown. Or the efforts could fall short and fail to energize the economy, leaving a clear impression that the mighty Fed is out of bullets – thus adding even more anxiety to an already dire situation.

I think it's on the second point, about credibility, that outside commenters have the most constructive role to play. Specifically, I for one promise to be super-nice to everyone associated with the Federal Reserve if it tries really really really hard to spark growth and it just turns out that Mark Thoma is right and this doesn't really work. But conversely it seems to me that the real credibility-killer for the Fed is if it meekly acquiesces in quarter after quarter of below-target growth in the price level while the country stays mired in high unemployment.

On bubbles, I'm not quite sure what to make of this. I suppose it's true that if we bring unemployment down, that does set us up for the prospect of a new recession leading to high unemployment. But simply reconciling ourselves to high unemployment doesn't help with that.

World War II and the End of Depression

In addition to everything else that's wrong with David Broder's invade Iran column, it's worth pointing out that wartime spending was hardly the reason for the US recovery from the Great Depression. Among other things, we had extremely strong growth in FDR's first term long before mobilization was under way. As Christina Romer explained (PDF) in her speech on "Lessons from the Great Depression

for Economic Recovery in 2009," the key measures were unorthodox monetary measures that don't have totally clear analogues today:

A second key lesson from the 1930s is that monetary expansion can help to heal an economy even when interest rates are near zero. In the same paper where I said fiscal policy was not key in the recovery from the Great Depression, I argued that monetary expansion was very useful. But, the monetary expansion took a surprising form: it was essentially a policy of quantitative easing conducted by the U.S. Treasury.

The United States was on a gold standard throughout the Depression. Part of the explanation for why the Federal Reserve did so little to counter the financial panics and economic decline was that it was fighting to defend the gold standard and maintain the prevailing fixed exchange rate. In April 1933, Roosevelt temporarily suspended the convertibility to gold and let the dollar depreciate substantially. When we went back on gold at the new higher price, large quantities of gold flowed into the U.S. Treasury from abroad. These gold inflows serendipitously continued throughout the mid-1930s, as political tensions mounted in Europe and investors sought the safety of U.S. assets.

Under a gold standard, the Treasury could increase the money supply without going through the Federal Reserve. It was allowed to issue gold certificates, which were interchangeable with Federal Reserve notes, on the basis of the gold it held. When gold flowed in, the Treasury issued more notes. The result was that the money supply, defined narrowly as currency and reserves, grew by nearly 17% per year between 1933 and 1936.

It seems to me that the closest contemporary versions of this are all things that do require coordination between the Fed and others—some kind of money-financed fiscal policy. That could be "helicopter drops" of money or infrastructure spending financed by printing money or both. A more modest step along these lines that we definitely should be taking is to stop paying interest on bank reserves, thus giving a small nudge in the direction of getting more money circulating.

October 31, 2010

War With Iran Unlikely to Spur Growth

My colleague Matt Duss finds David Broder arguing that "as tensions rise and we accelerate preparations for war [with Iran], the economy will improve". I had sort of considered writing a satirical piece along these lines, though my proposed plan of attack was going to be join US-EU military operations against Canada and Norway.

At any rate, Broder is kind of enough to observe the questionable moral logic here and hastens to add "I am not suggesting, of course, that the president incite a war to get reelected." The economics, however, is questionable. It's true that a net increase in government purchases would increase economic growth. But as Dean Baker notes one hardly needs a war to produce a net increase in government purchases: "If spending on war can provide jobs and lift the economy then so can spending on roads, weatherizing homes, or educating our kids." The point is that anything that mobilizes real resources will fight idleness and unemployment. What's wanted, however, is to mobilize real resources in order to do something useful.

One should also consider the very real possibility that war with Iran would lead to a depression inducing supply-side shock through a spike in energy prices. Even worse, war is bad for children and other living things! An alternative military stimulus would just involve doing the stepped-up military purchases but then doing absolutely nothing with the new equipment and personnel. That would have the same economic impact, but nobody would need to die.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers