Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2514

October 29, 2010

Endgame

I'm all about them:

— Troops have no problem serving with gay soldiers.

— Why Mike Konczal is a climate hawk.

— Jefferson, Hamilton, and today's American progressives.

— Jonah Goldberg, well-known critic of liberal fascism, wonders: "Why wasn't Assange garroted in his hotel room years ago?"

— Should we legislate against street harassment?

Sleigh Bells, "Rill Rill"

The Party of Medicare

Excellent article from Shikha Dalmia about the Party of Medicare:

For starters, polls by the New York Times and Bloomberg have found that although a vast majority of Tea Party supporters favor smaller government, they don't want cuts in their Medicare or Social Security, a contradiction perfectly captured in a sign at a Tea Party rally: "Keep the Guvmint out of my Medicare." Indeed, the Bloomberg poll discovered that even though Tea Partiers dislike ObamaCare, they want Medicare to offer more drug benefits and the government to force insurance companies to cover pre-existing conditions. [...]

Kentucky's Rand Paul, who is running as an uncompromising apostle of limited government and free markets, has pulled the most distressing switcheroo of them all. A doctor himself, he denounced Medicare as socialized medicine. Yet he has balked at the idea of cutting physician salaries, even though American physicians make twice as much as doctors in OECD countries. Why? Because their cartel, the American Medical Association, both restricts the supply of physicians through insanely restrictive licensure requirements and controls the Medicare board that determines physician compensation, as the Wall Street Journal reported this week. Yet, Paul now maintains: "Physicians should be allowed to make a comfortable living." (But he is just being fair – not pleading for his special interest of course!) Likewise, after calling Social Security a Ponzi scheme, Paul is now talking less about reforming it and more about protecting it for those now reaching retirement age.

I think the biggest thing to watch for is a sharp pivot toward a strategy of pure generational warfare. Pay out 100% of promised benefits to the over 55 crowd and massively slash benefits for people under 40.

The Folly of Empire

MG Siegler has an interesting TechCrunch item about Microsoft's eye-popping losses in its online business:

Microsoft released their Q1 2011 earnings today. The results were very good except for one very big blemish: the Online Division. Last quarter, the division lost $560 million for Microsoft. That's better than the previous quarter when it lost a staggering $696 million, but it's much worse than a year ago, when it lost $477 million. In the past year, Microsoft has lost well over $2 billion from the division.

Let me repeat that: 1 year, a $2 billion loss.

Obviously, any startup that did that would have long since gone under — with that kind of burn rate, they probably would have gotten the plug pulled a few weeks into existence no matter how well-funded they were. But Microsoft keeps pumping money into the division. And they have to. Because even they realize it's the future.

There's an interesting divergence here between the perspective of Microsoft qua institution and Microsoft as a cooperative enterprise undertaken for the benefit of its shareholders. The conventional wisdom is that Microsoft needs to expand beyond its super-profitable core businesses because "[t]he web is making Windows (and every operating system) less vital, while at the same time coming up with free and/or cheap tools to replace the relatively expensive Office." Therefore, the smart strategy for Microsoft is to take the giant profit margins of Office and Windows and plow them into new ventures.

An alternative approach would be to just say "we've got a great core business here that's still great today and may or may not be obsolete in the future, so we're just going to keep doing what we do well and pay out giant dividends."

In practice that never happens. As firms like Microsoft mature, they do start paying dividends, but they never really go "all in." Psychologically, successful business executives are bound to regard themselves as above-average businessmen who can maximize shareholder value by keeping profits in-house. And from a talent-retention/recruitment perspective it would probably seem demoralizing to just say "eh, we're giving up on growth." And of course it's more fun to be the CEO of a large growing firm that's a vital player on the cutting edges of technology than to preside over a stagnant-though-wealthy mechanism for funneling billions of dollars from corporate IT departments to shareholders. And in practice, the logistics of hostile takeovers are horrible and they're rarely attempted.

And Microsoft is by no means unusual in this regard. Google is very aggressively pushing into new businesses instead of sitting on its existing cash cows, and Apple has a famously gigantic cash stockpile being presumably conserved for some nebulous future M&A activity.

The Disastrous Health Care Phase-in

It seems to me that if you want to write about a health care-related political error, the thing to focus on is the exquisitely slow pace at which the Affordable Care Act will be phased on. If you're an ACA-supporter, which presumably the people who voted "yes" on the program are, you have to believe that this is a good program that, when in place, people will like. But since the main benefits won't exist until 2014, that means ACA proponents need to go through the 2010 and 2012 cycles with few concrete benefits to point to.

What's more, the phase-in is so delayed for pretty crassly political reasons—it made the short-term CBO score look better. So the moderate members of congress and White House operatives who put so much weight on that CBO score really ought to be looking around the country and asking themselves how much benefit their reaping from that score today? As best I can tell, no benefit whatsoever. By contrast, members with a program to point to could say "hey, this guy wants to take your program away!" At a minimum, folks who like the ACA might have more morale if it were actually in place.

The Case for a King

I agree with Jon Chait about the "trouble with presidential dignity":

On the contrary, I think the office of the president has too much dignity. The president is a citizen who serves the public. It is in the interest of the president to make himself into something exalted, a national father figure and symbol of the government. But the public has no interest in this function, which, indeed, can take on monarchical trappings with an insidious anti-democratic undertone. (It's a little disturbing when people who see the president salute — a military signal that suggests subordination.)

Obviously, I don't want to see presidents cutting their own rap videos or jumping into the ring with professional wrestlers. But at the moment, and for the foreseeable future, out problem is not too little presidential dignity but too much.

In some ways I would say the whole thing highlights a problem with republican government that wasn't appreciated or foreseeable in the late 18th century. Since that time, many democracies—from Canada to Spain to Sweden and beyond—have hit upon the idea of denying the monarchical glow to their head of government by keeping the monarch around but denuding him/her of governing authority. Some countries, such as Germany, India, and Israel, try to have a powerless "president" fill this role but I think it doesn't really work. Such people have too much democratic legitimacy and too little pomp and circumstance to adequately fill the king role.

So does America need a king and queen with the President demoted to a more drab functional role? I say: Perhaps. At a minimum, America's Next First Couple could be the world's greatest reality TV show.

My preferred candidate for Queen would be Princess Märtha-Louise of Norway who's basically out of the running for succession there (fourth in line) and who conveniently already lives in the USA. She's author of the children's book Why Kings And Queens Don't Wear Crowns, and the Norwegian royal family is one of the youngest in Europe. Märtha-Louise's great-grandfather was born in Denmark and elected King of Norway in 1905.

A New Hope

(cc photo by futureatlas)

Noam Scheiber describes a long ball move the White House could deploy to get around congressional obstruction of efforts to fix the economy. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac own an awful lot of mortgages. And the executive branch owns Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Fannie and Freddie can simply write down the principal on the loans they're owed—bailout—and then Treasury can "loan" them the money to cover the loss knowing full well it'll never be repayed:

Now it's true that congressional Republicans would never go for this. (You can imagine the White House pitch to GOP leaders: We hear what you're saying about another $100 billion in spending. How bout $1 trillion for mortgage-debt relief?) The good news is that the administration could do it without congressional approval. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac basically have an unlimited credit line with the U.S. Treasury, and the government has controlled Fannie and Freddie since it seized them in 2008. The mechanics would be hairy: How do you decide which mortgages to write-down? Do you only write-down mortgages Fannie and Freddie already own, or do you have Fannie and Freddie go out and buy new ones? If it's the latter, do Fannie and Freddie eat the whole cost themselves, or do they split the losses with banks? Etc., etc. But the bottom line is that it can be done.

The far bigger obstacle is the politics. Suffice it to say, if you thought the bank bailout and the stimulus went down badly, then watch how the Tea Partiers react if the government spends a $1 trillion without so much as asking Congress. This is obviously why the administration quickly shot down rumors of a homeowner bailout when they cropped up this summer. And it's probably why it will never happen. But before you sneer, ask yourself the following: Will Barack Obama be in better shape two years from now with the economy humming along and an apoplectic Tea Party movement, or with 9 percent unemployment and a slightly less apoplectic Tea Party movement?

I would go stronger than Scheiber. If the White House does this in 2011 it will have zero impact on the 2012 Presidential election. And it will have zero impact on the 2012 Senate elections. And it will have zero impact on the 2012 House elections. The evidence is overwhelming that absolutely nothing done in 2011 will impact 2012 elections. Conversely, the rate of real personal disposable income growth in 2012 will have a giant impact on the 2012 Presidential elections and a meaningful impact on the House and Senate elections. Which is to say that if the economic team thinks it can draw up a feasible plan here that will boost the economy they should absolutely do it.

I note that the substantive problem here is that if the US government deliberates takes on a trillion dollars in additional debt, that may lead the interest rate the US government needs to pay on its debt to rise. Rising interest rates on treasuries will increase interest rates throughout the economy and hurt growth. This is the dread "crowding out," but it could be easily prevented by quantitative easing from the Fed. So the question is not whether the public would stand for this (they wouldn't, but they would get over it quickly) it's whether Ben Bernanke and the FOMC would stand for it. With inflation well below target and huge levels of unemployment and idle capacity they should stand ready to support this action but they very possibly won't.

Note that when FDR was fighting the Depression he found the need to exploit all kinds of weird legal loopholes to take unilateral action.

The biggest problem with this idea, as far as I can tell, is that our policy guys here at CAP have some real doubts as to whether the idea is really as legal as Scheiber says. The proposal seems to have originated as a kind of paranoid "this is Obama's secret plan" kind of thing, rather than as an actual proposal, and there are real doubts as to whether the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 actually authorizes this.

I Am Rankled By Ben Bernanke's Reluctance to Be More Outspoken

"Bernanke's Reluctance to Speak Out Rankles Some", reports Sewell Chan in the New York Times. And after reading the article, I too am among the ranks of the rankled:

The Federal Reserve is all but certain next week to begin a multibillion-dollar effort to coax the recovery along, but privately, Ben S. Bernanke, the chairman, worries that more is needed to turn the sluggish economy around and revive employment.

He believes that without the Obama administration's $787 billion stimulus program, the nation would have been worse off, and that Congress needs to continue to prop up the economy in the short run. He agrees that fiscal measures to support the recovery would probably make the Fed's unconventional monetary policy more potent.

But Mr. Bernanke has been reluctant to prominently voice those views, which were gleaned from testimony, speeches and interviews with people close to him over the last several months. His predecessor, Alan Greenspan, did not display such hesitation, advocating for the Bush tax cuts of 2001 and 2003.

So, yes, I'm rankled. And I'm especially rankled because I think Bernanke is making his own life harder than it needs to be with this approach. It's clear that one reason some people are voicing skepticism of unorthodox monetary measures is that they see advocacy for quantitative easing as undermining the case for fiscal policy. But Bernanke believes, as do I, that QE and fiscal expansion go best together. So if he would say that clearly he would have, at a minimum, some more allies out there.

In general, I think the reluctance of fiscal and monetary authorities to talk to the public about the interplay between the two has been very costly to the political class's understanding of the situation. For example in her March 2009 speech on "Lessons from the Great Depression" (PDF), Christina Romer first explained that monetary expansion was absolutely critical to ending the Depression and then said "A key rule of my current job is that I do not comment on Federal Reserve policy." But given that, "In the same paper where I said fiscal policy was not key in the recovery from the Great Depression, I argued that monetary expansion was very useful" it's obviously very difficult to draw Romeresque lessons about the Depression that involve commenting on the Fed.

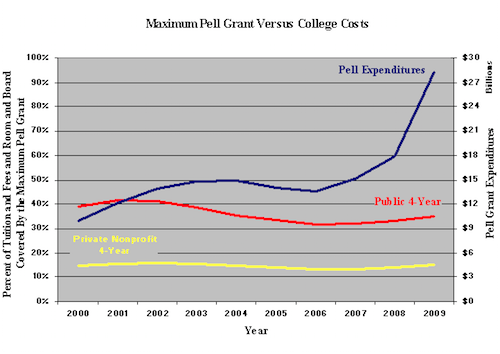

Pell Grants Can't Save America From Ever-Higher College Tuition Costs

Here's a sobering chart from Ben Miller showing the limited impact of huge increases in Pell Grant generosity on the actual affordability of higher education:

The red and yellow lines are the Pell grant's buying power—what percent of a sector's average tuition and fees and room and board are covered by a maximum Pell Grant. And what these lines show should be incredibly frustrating. In exchange for substantial growth in the program costs, Pell's buying power at nonprofit four-year institutions has stayed at about 15 percent; at public institutions it declined from 39 percent to 35 percent. If you extend the window back to 1990, the picture is even worse–the buying power of the Pell Grant dropped 10 percentage points at public four-year colleges. Maybe the picture would be slightly better if it could take into account multiple Pell awards for a student, but it wouldn't get back up to the 45 percent level.

At public institutions, this in part reflects state legislatures' tendency to disinvest in higher education. That, in turn, is in part driven by shortsightedness and in part driven by rising health care costs tending to squeeze out appropriations for all other functions. At private schools, however, it simply reflects the fact that as currently structured American institutions of higher education have no real incentive to expend energy on improving value. Sometimes colleges do find ways to reduce the cost of providing education, but even when they do so they don't return the savings to customers in the form of lower prices, they just find new things to spend the money on.

Meanwhile, as Miller says the rate of increase in Pell Grants sparked by the 2006 election can't continue at this pace. Something more fundamental needs to be done to transform the system.

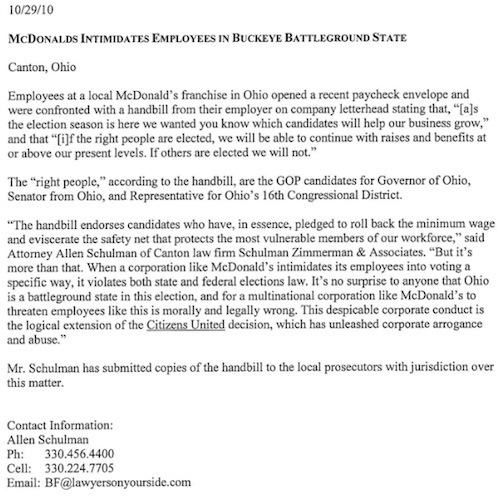

McDonald's Telling Employees How to Vote in Ohio

I remember when we were debating campaign finance laws around the turn of the millenium and the standard right-of-center view was that these were unfair restrictions on free speech and disclosure alone would be good enough. Then came Citizens United and the DISCLOSE Act and suddenly disclosure itself was an unbearable curtailment of free speech. Now I'm reading about this story where a McDonald's in Ohio is sending notes in its employees' paychecks telling them who to vote for:

I assume that this, too, is constitutionally protected free speech.

Meanwhile, looking at everything from the conduct of the US Chamber of Commerce to this McDonald's franchise, I'm continually gobsmacked by the number of business executives in the United States who haven't read Tim Carney's book and don't realize that Obama is just a patsy for the big business agenda. Maybe the White House should buy a free copy of Obamanomics for every corporate headquarters in the country.

Deadweight Loss

Katy Perry in Berlin

Alex Tabarrok takes a stab at popularizing the concept of "deadweight loss." It's an important one, but I think it's unfortunate that his chosen example draws specifically from the realm of excise taxes where I think the general spirit of the point ("taxes impose losses") is pretty well-understood.

What about the case of unauthorized downloading of music files. Consider Katy Perry's "California Gurls". This tune costs $1.29 on iTunes. At that price, some people will buy it. Others will refuse. You might refuse because you hate Katy Perry and hate the idea of owning one of her songs. But say you're not a hater. You're just a skeptic and a cheapskate. You'd gladly pay a dime for the song were that an option, and since the marginal cost of distribution is basically zero it would be profitable to sell you the song for a dime. But it's not an option, since the overal profit-maximizing price is $1.29. And say there are a million people like you out there. That adds up to $100,000 in deadweight loss—the value of the transactions blocked by copyright protection.

Of course in the real world many of those million people will just download a copy of the song for free. Some would like you to believe that this is an action that should be analogized to hijacking a ship, threatening to murder its crew, and then stealing the ship's cargo. But unlike piracy, unauthorized copying can often be highly welfare-enhancing because of deadweight loss. Similarly, even though everyone seems to hate price discrimination, deadweight loss means it can be welfare enhancing as well since more precisely tailored pricing lets firms give some folks a discount.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers