Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2523

October 21, 2010

The High Fiscal Cost of Short Buildings

(cc photo by cbowns)

I continue to agree with Ryan Avent on the (lack of) merits of DC's super-strict restrictions on building height (though I think he's a bit too optimistic here about the possibility of deregulation substantially altering the mix of business functions found in the city), and was glad to see him point to the existence of a study indicating that a modest 30-foot increase in the height limit "could generate an additional $10 billion in tax revenue over 20 years if it raised the height limit to 160 feet."

To get a sense of the scale of that, the Fiscal Year 2011 budget (PDF) anticipate $0.9 billion in revenue from the city's 10 percent sales tax. In other words, a very modest increase in the size of downtown office buildings would probably let us cut sales taxes from 10 percent to 5 percent. That would be an absolute boon for the city's poor residents, to say nothing of making it easier for local entrepreneurs to start successful businesses.

And that would be a very modest increase. The tallest building in Providence, Rhode Island is 428 feet tall and Providence is hardly a town where the sun's been blotted out. Pittsburgh has an 841 foot building.

I'm not sure a free-ish market in downtown office buildings would generate anything as tall as the US Steel Tower, but it would certainly generate buildings taller than 160 feet and far more than $10 billion in additional tax revenue over a twenty year window. That would finance not only a cut in the retail sales tax, but construction of a streetcar system, more frequent buses, more cops, and better-maintained streets and sidewalks to say nothing of additional employment opportunities for the city's working class residents or the enhanced ecological sustainability of the entire region.

On the other hand, some people's view of the Washington Monument would be messed up.

Code-Switching and the Culture of Poverty

I linked to it last night and praised in on Twitter, but I wanted to specifically post on Ta-Nehisi Coates brilliant piece reconceptualizing the "culture of poverty" concept as a form of code-switching. His analysis seems correct to me, and also a useful way to perhaps ratchet-down the level of emotion and victim-blaming that often attaches to this whole conversation. The point is that, basically, we all understand that when you go from place to place there are different kind of norms and that to succeed in any given context you have to understand the relevant norms and abide by them. And in the United States of America there's a substantial gap between the norms that prevail on "the street" and those that prevail in middle-class society.

This is all related to the very important and insufficiently discussed paper by Greg Duncan, Ariel Kalil, Susan Mayer, Robin Tepper, and Monique Payne "The Apple Does Not Fall Far From the Tree" (PDF) which indicates that a large number of poor children seem to pick up attributes that tend to keep them in poverty by imitating parental role models. In Coates' terms, just as kids learn to speak their parents' language they tend to instinctively pick up their parents' locally adaptive norms, norms that may not be ideal to carry over into other contexts.

I would conjecture that this sort of thing explains a large part of the success of the more successful kind of educational interventions. Nurse home visits and high-quality preschool both involve injecting a more bourgeois presence into a kid's life at formative moments, and KIPP explicitly instructs poor children in modes of behavior that middle class white people deem appropriate. This is all kind of condescending and distasteful, but it seems to work. And it's not really so strange that a bit of condescension works to help people adapt to novel situations—I was only able to exchange business cards with Chinese people in the appropriate way because someone explicitly told me how to do it. There's nothing "wrong" about the western way of doing it, but if you're in Asia you need to make an effort to do things the Asian way.

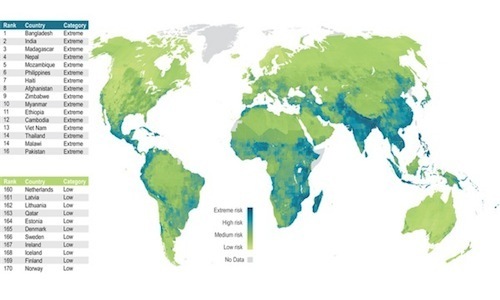

Map of Coming Climate Doom

Via Paul Kedrosky, the British risk analysis firm Maplecroft tries to assess relative vulnerability to climate shocks. More northerly ones and also richer ones are viewed as less exposed, and the assumption here seems to be that the Dutch have the resources and engineering chops to build as many seawalls as necessary to keep their towns from drowning:

In light of continuing discussion over the Koch Brothers' allegedly selfless devotion to the principle that fossil fuel companies should be allowed to wreck the planet without regulation in the name of free markets, it's worth pondering this. Presumably "I should be allowed to murder this Bangladeshi man and steal his money for profit" is not a free market position. Presumably "I should be allowed to steal this Bangladeshi man's land and sell it for profit" is not a free market position. Nor is "I should be allowed to have my cattle eat this Bangladeshi man's grass and then sell it for profit" a free market position. I don't think "I should be allowed to cut costs by dumping the toxic waste byproducts from my family on this Bangladeshi man's agricultural land" makes a ton of sense as a free market position.

Which is just to say the fact that current "free market" orthodoxy holds that in a properly functioning market business executives have an untrammeled right to pollute the world's commonly owned air supply without paying any compensation is a reflection of the political and intellectual influence of pollution interests' money. A world in which the financiers of rightwing politics were abstractly interested in property rights and classical liberalism would be one in which the right was demanding carbon taxes.

On Juan Williams

Since my ThinkProgress colleagues are sort of "part of the story" in terms of Juan Williams getting sacked from NPR I'm a bit hesitant to comment on it. But as in the case of Rick Sanchez it seems to me that if you assume Williams has been doing valuable work all these years, firing him over this single incident is excessive. But as an NPR listener, I'm a good deal more familiar with Williams' work than I am with Sanchez's and it seems clear to me that Williams has not, in fact, been doing valuable work all these years. If Williams had never made these remarks about Muslims and NPR announced his firing this morning on the grounds of general lameness and lack of valuable contribution to their programming, I would have applauded the move so I'm hardly going to deplore what actually happened.

At any rate, my local NPR affiliate WAMU is one of the charitable organizations I normally donate to and their currently in the middle of a pledge drive. All things considered a Williams-less NPR is one I'm more inclined to support than a Williams-full one so I just re-upped my membership.

QE Can Be Made to Work

Annie Lowrey writes for Slate that most economists are not hopeful about the prospects for a new round of "quantitative easing" to improve the economic outlook. As previously, I continue to be frustrated when people express a political skepticism about the Federal Reserve's likely willingness to do what's necessary as skepticism about the Fed's ability in principle to help solve problems.

For example here:

Another hope is that by trading non-interest-bearing assets (cash) for interest-bearing assets (bonds), the Federal Reserve will reduce the supply of bonds and make them more expensive, prodding big institutional investors to invest less in government debt and more in the American economy. The problem with this theory is that the bond market is huge—really huge—and international. To have any sort of impact, the Fed would need to buy a lot of bonds. Economists worry it won't buy enough. Paul Krugman, for one, says the Fed would need $8 trillion to $10 trillion to have an effect.

I'm a political pundit, not an economist. But qua political pundit, it seems to me that if economists think the way to fix the economy is for the Fed to buy $8-10 trillion in bonds, then Ben Bernanke should say "I'm determined to fix the economy and am willing to buy as many bonds as necessary to make it work—if that means $10 trillion then so be it."

One key point that Lowrey makes is that currently cash-rich firms are disinclined to invest and reserve-rich banks are disinclined to lend. She notes that this makes additional "credit easing" unlikely to work. But I think it also speaks to the importance of an attitude of gritty determination. If the Fed is saying "demand and the price level are going to rise, damnit, even if it takes $10 trillion in bond purchases" then maybe your cash-rich firms and reserve-rich banks are going to think about doing something. But if the Fed keeps saying "everything will suck for the foreseeable future and we're okay with that" then of course businesses won't expand and invest. Would you?

Last I note that some, including most recently Joe Stiglitz, seem to think that talking about this makes expansionary fiscal policy less likely. I don't really see it that way. For one thing, the looming midterms make expansionary fiscal policy totally impossible politically so there's no real way for it to get less possible. But more importantly, in policy terms fiscal policy only works if monetary policy accommodates it. One of the main motives for the United Kingdom's looming dangerous experiment in fiscal austerity is fear that the Bank of England won't stand for continued deficits. Signals from the Fed that it wants to see the price level pushed up are crucial to making any fiscal measures work.

Bank Bailout = Profit

Last time I wrote about what a great deal TARP had been for taxpayers, I wrote a little bit too broadly. The program gave very broad discretionary authority to the Treasury some of which was deployed for money-losing purposes. But the really hateful and unpopular thing about TARP is that it gave all this money to big banks—the very people responsible for the crisis in the first place! Insane! Unforgivable! But as Yalman Onaran and Alexis Leondis write for businessweek if you look narrowly at the bailing out of financial institutions this looks even better as a strictly fiscal measure:

The U.S. government's bailout of financial firms through the Troubled Asset Relief Program provided taxpayers with higher returns than yields paid on 30- year Treasury bonds — enough money to fund the Securities and Exchange Commission for the next two decades.

The government has earned $25.2 billion on its investment of $309 billion in banks and insurance companies, an 8.2 percent return over two years, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. That beat U.S. Treasuries, high-yield savings accounts, money- market funds and certificates of deposit. Investing in the stock market or gold would have paid off better.

Dean Baker and others have argued, plausibly, that TARP wasn't nearly as "necessary" as Bush/Paulson/Bernanke persuaded the congress that it was. There were, the case goes, alternate measures that the government could have undertaken to avoid total collapse. TARP just happens to have been the collapse-evasion method that the powers that be liked best because distress to the princes of Wall Street.

That may all be true. And indeed it would be a minor miracle of a program hastily assembled in the waning days of the Bush administration and implemented largely during a chaotic lame duck and administration transition phase were optimal. The counterpoint, however, is right there in the Businessweek story. Bailing out the banks "cost" a negative sum of money. It was a highly profitable mobilization of the government's risk-bearing capacity. And when you do a cost-benefit analysis on a program with negative costs you find that even modest and speculative benefits end up looking great.

October 20, 2010

Endgame

Just keep it in its box:

— If Newsweek goes out of business where will we get this great polyamory coverage.

— Ta-Nehisi Coates is utterly brilliant on the "culture of poverty."

— Don Rumsfeld on Twitter.

— Bin Laden channels William Easterly.

In honor of the one-day trip to NYC I'm on the way back from, it's The Kills "What New York Used to Be".

Wave of Election Analysis

(cc photo by vår resa)

Jamelle Bouie an interesting speculation from Charlie Cook that I think may be wrong:

The one sobering thought that veteran Republican consultants are already contemplating is that the larger the wave this year, the more difficult it will be to hold onto some of these seats in 2012 and 2014 in the House and 2016 in the Senate. The bigger the wave, the weaker the class and the harder it will be to hold onto those seats. Democrats only have to look at their 2006 and 2008 classes for plenty of examples. What this means is that we will likely have our third wave election in a row this year, and the bigger this one is, the more likely that there will be a countervailing wave in either 2012 or 2014.

Obviously a lot of this hinges on what we make of the concept "wave election." But let's just say a "wave" election is one in which one party makes large gains and a "non-wave" election is one in which the net change in seats is small.

In that framework, what I think Cook's analysis misses is that the current Democratic majority is very large. Consequently, for the GOP to obtain even a small majority would require a "wave" of wins. But if they get a "wave" and a small majority, there's nothing about "small GOP majority" that should lead us to expect a future wave. It's only if Republicans win a gigantic net gain of 70-75 seats that would leave them in the position of holding many Democratic-leaning districts.

The Problem With Pakistan: They Want Different Stuff Than We Do

I don't share Joshua Foust's semi-personal level of animus toward Zalmay Khalilzad but I think Foust's critique of Khalilzad's latest offering makes some extremely valuable general points. Khalilzad starts out with a banal point masquerading as insight derived from on-the-ground experience:

When I visited Kabul a few weeks ago, President Hamid Karzai told me that the United States has yet to offer a credible strategy for how to resolve a critical issue: Pakistan's role in the war in Afghanistan.

But of course everyone knows this and the problem is that it's hard! The rest of the piece doesn't really offer any particularly compelling ideas.

Foust:

Most of Khalilzad's ideas are not ideas at all, but rather an advocacy for the continuation of the status quo. That is not in and of itself a bad thing, but his ideas for "tweaking" the current state of affairs–more unilateral strikes on Pakistani territory, a general tone of "forcing" Pakistan to do something that is clearly against its interests, and so on–simply don't make any sense. The last nine years of U.S.-Pakistani relations have been variations on that same theme: forcing Pakistan to do things it is not otherwise inclined to do. The result is a strained relationship and deep, perhaps permanent opposition to the U.S. in domestic Pakistani politics. We are worse off because of it.

It seems to me that oftentimes it's useful to just go look at a map. Afghanistan is right there next to Pakistan. And it always will be. The United States of America is way over on a different continent. And it always will be. Then there's India on the other side of Pakistan. So Pakistan is always going to care more about the details of what's happening in Afghanistan than America does. And Pakistan is always going to care more about India than it does about the United States. We're not impotent to shape Pakistan's dealings with all this, but it's foolish to think we can somehow play a dominant role in determining what the Pakistani government wants to do in the immediate vicinity of Pakistan.

What I think we need to think harder about is what do we care about. It seems kind of perverse to me to look at this whole region and decide to make Afghanistan the pivot around which all our priorities turn. It's one thing to have a short-term region-wide (indeed, global) focus on Afghanistan for the purposes of a "get Osama" mission. But does anyone think that in 2060 America's relationship with Afghanistan will be more important than our relationship with India? That Pakistan's relationship with Afghanistan will be the centerpiece of the US-Pakistan bilateral relationship?

Dairy Checkoff

We have a program in this country called the "dairy checkoff" which levies a kind of tax on dairy producers and uses the funds to promote dairy products. But what specifically does that entail? Marion Nestle delves into the latest USDA report and finds, among other things:

— Focusing on dairy health and wellness by helping to combat childhood obesity by encouraging schools to implement physical activity and good nutrition, including dairy.

— Partnering with Domino's Pizza to develop pizzas using up 40% more cheese than usual. This worked so well that other pizza chains are doing the same thing.

— Partnering with McDonald's to launch McCafe specialty coffees that use up to 80 percent milk, and three new burgers with two slices of cheese per sandwich. The result? An additional 6 million pounds of cheese sold.

— Creating reduced lactose milks in order to bring lapsed consumers back to milk. The potential result? An additional 2.5 to 5 billion pounds of milk each year.

— Partnering with General Mills' Yoplait to develop yogurt chip technology that requires 8 ounces of milk.

— Maintaining momentum for single-serve milk by offering white and flavored milk in single-serve, plastic, resealable bottles.

40 percent more cheese! This was sent to me by a reader who suggests, rightly, that it's probably relevant to the discussion of why there are no ads for brocoli.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers