Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2483

December 1, 2010

WikiLeaks and Distrust

Jack Shafer says he loves WikiLeaks because it "restores our distrust in the institutions that control our lives."

But does it? I've seen Shafer's piece praised by a number of online commentators who I would say were previously characterized by massive distrust of the American government. And Shafer, too, was already a government-distrusting libertarian. I, personally, was less of a distruster than Shafer or Glenn Greenwald pre-WikiLeaks but still more of a skeptic than, say, Fred Hiatt is. And after "cablegate" I'd say I'm still between Greenwald and Hiatt in my level of trust for America's elite national security institutions. And Hiatt, too, is exactly where he was. In terms of moving the needle on trust this seems to me to have been a total nothingburger. Instead of the cables changing people's level of trust, people's pre-existing level of trust seems to be an important determinant of their emotional response to WikiLeaks.

Undead Technology

One of David Pogue's key lessons learned from ten years as a technology reporter:

Things don't replace things; they just splinter. I can't tell you how exhausting it is to keep hearing pundits say that some product is the "iPhone killer" or the "Kindle killer." Listen, dudes: the history of consumer tech is branching, not replacing.

That seems correct to me, but also perhaps a little too fast. Did book-binding replace scrolls? Not really. Just attend a Bar Mitzvah and you'll see a 13 year-old reading from a scroll. But while scrolls aren't dead, I'd say they're pretty damn marginal. You might think of them as undead. In a similar vein, people still read verse—I've read the Odyssey and Eugene Onegin and The Merchant of Venice and I'm hardly the only one—but this isn't really a vital mode of composition in contemporary culture. Heck, thanks to poor cell phone reception in my apartment I even own a landline.

Pogue's point is that human culture is fundamentally additive; it's rare for things to just go away. But there are also constraints on splintering. A given person only lives so long, a given day only contains so many hours, you can only carry so much stuff at once. So squeezing happens. Over the past decade, consumer electronics innovation has tended not to squeeze out other consumer electronics products, but I think we have seen consumer electronics do a fair amount to squeeze out things that aren't consumer electronics. I read books (including ebooks) less than I did ten years ago because books now need to compete with lots of other stuff for my attention.

Bowles-Simpson vs Current Law

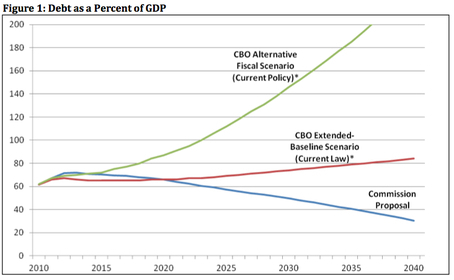

Surely the strangest thing about the Bowles-Simpson debt reduction plan is that, relative to current law, it . . . increases the public debt load over the next ten years:

Obviously starting around 2020 or so Bowles-Simpson starts doing better than current law, but it's difficult for the current congress to tie the hands of future congress. After all, the whole point of the "alternative fiscal scenario" baseline is that past law doesn't bind the hands of the current congress. The AFS is preferred my many as more politically realistic than the current law baseline, which is fair enough. But wouldn't it be easier politically to stick with current law than to do Simpson-Bowles' huge series of unpopular changes? After all, the American political system has a ton of veto points. Barack Obama saying "I will veto any laws that increase the deficit relative to current law" would do more to reduce the debt over the next 2 or 6 years than would adopting Simpson-Bowles.

The Strategy of WikiLeaks

Ezra Klein on the likely consequences of WikiLeaking:

Assange isn't whistleblowing or leaking. Both of those are targeted acts focused on an identified wrongdoing or event. He's simply taking the private and making it public, with relatively little in the way of discrimination. If he's really effective, the likely outcome won't be that people know more, but that they know less, as major institutions — both public and private — will stop sharing their information so widely internally and stop writing so much of it down. That means decision-makers will know less, bureaucrats and managers will know less, reporters will know less, historians will know less, and so on. Assange may think his target is the U.S. government, or Goldman Sachs. But at the end of the day, there will still be governments and there will still be banks. What Assange is really doing is turning them against electronic text, file storage and large internal networks.

I think that's essentially correct. But as zunguzungu explains in a excellent WikiLeaks-sympathetic post this is likely Julian Assange's actual strategy and not some failure on his part. The post is longish and worth reading, but I think this is the key excerpt:

[H]is underlying insight is simple and, I think, compelling: while an organization structured by direct and open lines of communication will be much more vulnerable to outside penetration, the more opaque it becomes to itself (as a defense against the outside gaze), the less able it will be to "think" as a system, to communicate with itself. The more conspiratorial it becomes, in a certain sense, the less effective it will be as a conspiracy. The more closed the network is to outside intrusion, the less able it is to engage with that which is outside itself (true hacker theorizing).

The short-term consequence of random but massive leaking of an organization's internal communications will be more information and more disclosure. But the response will be tighter control over information, and even less disclosure. The key turn here, however, is that the more an institution is focused on clamping down on the internal dissemination of information (in order to prevent leaks) the less effective that institution will be. So if you have a radical critique of the American national security state (as Assange certainly seems to) the bug Klein is pointing to starts to look like a feature.

Job Creators Don't Need Money to Create Jobs, They Need Customers

To add a little bit to what Jon Chait has to say about Rep John Shadegg the whole notion that you drive the economy forward by directing more money into the hands of "job creators" (i.e., rich people) makes basically no sense. A job creator is basically a businessman with an idea. If it's a good idea, a business based around his idea will attract customers. And if it attracts customers, he'll hire employees to serve those customers' needs. This is where growth comes from.

But a businessman with a good idea who needs capital doesn't need a tax cut to get that capital, he needs a loan or an equity investment. This is what we have a financial system for. Sergey Brin doesn't need to first get rich, then finance Google out of his own pocket. He just needs to start Google and that's how he gets rich.

The thing of it is, though, that your idea really only works if you have some customers. If everyone in Yuma, Arizona is unemployed then even a very competent proprietor of a dry cleaning establishment is going to have a hard time expanding his business. He won't take out a loan to expand, he won't get an equity investment to expand, and he won't invest his own money in an expansion. You can give the guy all the money you want, and he won't invest in expanding his business. That's because unemployed people don't need much dry cleaning and also don't have much money to spend on dry cleaning. A guy with $0 and a good idea and a lot of potential customers will find a way to start his business. A guy with $1 billion and a good idea and no potential customers is just a guy sitting on a huge stockpile of cash. Things like the availability of credit matter, but credit is currently available. What's not available is customers with money and an inclination to spend it. More government spending and more money-creation will lead to more purchases, more customers, more business expansion, and more hiring. Then people with good ideas will make a lot of money and complain about their high taxes.

Mike Pence is Not Impressing Bruce Bartlett

Bruce Bartlett hoped Mike Pence's big address on economic policy might reveal a Republican wrestling seriously with the world's economic problems. As a long-time Pence watcher, I assumed he'd just say something dumb. Bartlett has learned his lesson:

Unfortunately, Pence's speech was nothing of the kind. It was a hackneyed rehash of every simplistic idea ever floated on Larry Kudlow's TV show, which appears to be the only source of information Pence has on the economy. I don't know how else to explain his obsession with inflation, a strong dollar, Fed bashing, tax cuts and the gold standard. Pence could have given the same identical speech in 1980 and barely needed to change a word. In the Pence/Kudlow world it is always 1980–stagflation is the primary problem and tight money and tax cuts are the cures.

The problem is that stagflation isn't the problem today. We have stagnation all right, but the "flation" we are suffering from today doesn't stand for inflation, but deflation. But because it is always 1980, right wingers are incapable of seeing that monetary policy functions very, very differently in an inflationary and a deflationary environment. They seem utterly incapable of comprehending constraints like the zero-bound problem, which sets a floor on how low interest rates can go. They are also incapable of seeing the exchange value of the dollar except in macho terms, which demands that the dollar be strong at all times. That makes about as much sense as saying the price of oil or any other commodity should always be strong. That's obviously nuts, but the dollar is no different. It must be allowed to adjust freely for changes in supply and demand or the result will be imbalances–too much will be imported if the dollar is overvalued, too little exports, thus increasing American's international indebtedness. Indeed, it was right wing saint Milton Friedman who taught economists the truth of this mechanism.

There do seem to be a lot of people, Pence among them, who have a weird amount of trouble with the idea that you do different things in different circumstances. If inflation's too high, you need tighter money—that's the early 1980s. But if nominal expenditures are too low, you need looser money. If high deficits are forcing the central bank to keep nominal interest rates high, you need a lower deficit—that's the early 1990s. But if nominal rates are at zero and total spending is still too low, then you need a bigger deficit.

The Plough and Gender Roles

Via Erik Voeten, a new paper from Alberto Alesina, Paola Giuliano, and Nathan Nunn indicates a link between gender roles and modes of agricultural production:

This paper studies the historic origins of current differences in norms and beliefs about the role of women in society. We show that, consistent with anthropological hypotheses, societies with a tradition of plough agriculture tend to have the belief that the natural place for women is inside the home and the natural place for men is outside the home. Looking across countries, subnational districts, ethnic groups and individuals, we identify a link between historic plough-use and a number of outcomes today, including female labor force participation, female participation in politics, female ownership of firms, the sex ratio and self-expressed attitudes about the role of women in society. Our identification exploits variation in the historic suitability of the environment of ancestors for growing crops that differentially benefitted from the adoption of the plough. We examine culture as a mechanism by looking at first and second generation immigrants with different cultural backgrounds living within the US.

Call me a cynic, but my guess is that this finding won't get the level of media attention we see every time an evolutionary psychologist publishes a study proving that men are from mars and women are from venus because we evolved to hunt antelope.

November 30, 2010

Endgame

A gentle company:

— The failure of economics education.

— Everyone hates TARP but it's actually awesome.

— Tweaking the DC comprehensive plan.

— Steve King wants you to know the president is .

— Home prices will probably keep falling a bit more.

Decemberists, "Los Angeles, I'm Yours".

Menu Labeling

Had some tacos for lunch in LA and what a pleasure it is to dine someplace you've never been in a jurisdiction with a menu labeling law (lesson learned—lengua tacos are low calorie compared to other meats). Readers will know that I'm a bigger booster of free markets than most American progressives, but the utter failure of the unregulated market for lunch to meet the "perfect information" standard of an idealized market seems very obvious. And there's no real political economy problem with the rule.

Something interesting to think about here is the different kind of equilibria you can reach. One knows from eating lunch in Washington DC that the market doesn't provide on-menu labeling of calories. But suppose we ran an experiment where DC implemented a menu labeling requirement for ten years, and then the requirement sunset. My overwhelming suspicion is that the vast majority of places would keep doing the labeling once the rule expired. When nobody does menu labeling, nobody seems to want to do it voluntarily. But if there was a pro-labeling norm in place, being the first restaurant to drop it would seem weird, like they had something to hide.

The Demand for Dollars

(cc photo by LateNightTaskForce)

The trouble in Europe seems to be getting worse, with debt fears spreading somewhat beyond even Spain to Belgium and Italy.

This is something people need to keep in mind when they think about QE2 and the fact that the real problem with current monetary policy is that it's not loose enough. One thing you're seeing as all this plays out in Europe is that the Euro is declining in value relative to the dollar. The dollar could go up for two kinds of reasons. One would be that foreigners are increasing their demand for US-made goods and services. They could be saying "I don't want these Italian financial assets, I'm going to go buy a Boeing jet." But obviously that's not what's happening here. Instead people are concerned about the increasingly rickety-looking European monetary system and want to get their hands on dollars as such.

The right response to this is for the Fed to be doing monetary stimulus—printing more money. This can take a number of forms. Buying longer-dated Treasuries seems to be what the FOMC is most comfortable with, but in a lot of ways I think it would be better to just create the money and send it to people. There are some questions about exactly how you would organize such a "helicopter drop" but I'm confident it could be worked out. And working those problems out would, among other things, have the advantage of improving the politics of monetary stimulus. Cut the banks out of the transmission mechanism and illustrate the fact that the point is to increase the amount of money that people have.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers