Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2481

December 3, 2010

Europe Needs Looser Money

Ruining everything

I've written about the need for looser monetary policy in the United States, but the situation is even worse in Europe. For one thing, as Ryan Avent points out looser money would help the European periphery regain competitiveness:

But the key to a relatively painless internal revaluation is inflation in tighter markets. And it's here that the European Central Bank could play a particularly useful role. Were the ECB to adopt a looser monetary policy, we would expect inflation to pick up first in the markets with the least excess capacity, and that would obviously mean rising prices for Germany.

The situation is kind of bitterly amusing. The Germans hate the idea of paying for bail-outs across Europe. They want peripheral countries to buckle down, slash their deficits, and accept as much of the pain of adjustment as they can. But the best thing Germany can do to facilitate this process is to allow the ECB to pursue a monetary policy that makes internal adjustment easier—by increasing inflation in Germany. And that's maybe the one thing Germans hate more than writing cheques to the Irish government.

But it's hardly all about inflation. Looser money would spur higher real output in Ireland, Spain, Greece, etc. all of which would make the deficits in those countries smaller. By contrast, it's not really clear what the "German" solution is supposed to look like—if debtor countries are going to borrow less, then either saver countries need to consume more or else world output needs to fall.

The IMF and Austerity

<

<

It's not the biggest deal in the world, but since I mentioned it once before it's worth noting that Kevin O'Rourke's dispatch from Dublin indicates that the IMF has abandoned its austerity-loving ways, but the European Central Bank is insisting that the people of Ireland indenture themselves to various banks:

The finger of blame was clearly pointed by the Minister of Finance, Brian Lenihan, and several of his colleagues: it was the European Central Bank and the Commission who had vetoed the proposal to force some of the bank losses back onto the bondholders. This interpretation is generally accepted in Dublin, although many observers also blame the Irish negotiating team for caving much too easily into pressure from Brussels and Frankfurt. The implication is that the IMF were the good guys: an unusual position for them to find themselves in, perhaps, and one with political implications in a country whose relationship with the European Union has been uneasy in recent years, and which has conserved close ties with the United States. On Monday night, an opposition spokesman made it clear that he would be much happier negotiating with the IMF, who are reasonable people, than with our European partners. The fallout from this will be toxic.

There are a bunch of reasons for this, but the key one is that if Irish taxpayers don't fully repay the debts of Irish banks, then that's going to leave some of the European banks who lent them money undercapitalized and in need of a bailout from taxpayers in the European "core." The austerity package is a way of trying to make sure the losses fall exclusively on Irish taxpayers, though realistically I can't imagine this deal being remotely sustainable.

December 2, 2010

Endgame

I want to know your shame:

— Peter Travers is confused, Galt Niederhoffer went to Harvard, her repugnant characters went to Yale. He's also wrong about the quality of the film.

— Evan Bayh is totally gay for repealing Don't Ask, Don't Tell.

— .

— Nanny-state behavior is perfectly appropriate when it .

— NASA discovers strange new arsenic-based life form.

Thermals, "I'm Gonna Change Your Life"

Credit Where Due: Korean Peninsula Edition

One structural problem in the world is that they don't hand out medals for the wars you don't fight, and the terrible potential consequences of roads you don't travel down don't wind up making the headlines. Consequently, policymakers who manage to face-down tricky situations without getting huge numbers of people killed end up overrated.

So I'd like to say that best on what I've read in recent news coverage and also what I've seen in the WikiLeaks cables, the governments of South Korea and the United States of America seem to have been doing a bang-up job for the past several years of managing a difficult situation. It's not as emotionally satisfying as being John McCain and randomly musing about "regime change" and it's not going to "solve" the problem, but it's protecting the relevant interests at a reasonable cost. And that, at the end of the day, is the job policymakers are supposed to do. It would be nice if the North Koreans weren't so bizarre and it would be nice if the PRC were more cooperative and it would be nice if the Bush administration hadn't blundered so badly in its first four years in office. But you have to work in the real people, and people dealt a bunch of bad options seem to me to be making the best of it.

The Questionable Prudence of the Savers

This is excellent from Steve Randy Waldmann on what's aggravating about a lot of the recent lectures about the perils of overconsumption:

Some people overconsumed relative to their income, and some people invested poorly. Those who overconsumed have mostly faced consequences for their misbehavior — they are either deeply in debt, or they have endured foreclosure or bankruptcy. But the people who invested absurdly, especially "savers" who lent money but permitted themselves ignorance and indifference to how their wealth would be mismanaged, have not suffered the costs of their recklessness. Instead, they have been almost entirely bailed out. It is lenders and investors more than any other group who determine the patterns of our macroeconomy. There are always people willing to overconsume or gamble on foolish enterprises. We do and must rely upon those with resources to steward to ensure those resources are used wisely. They did not, and their recklessness has brought us to catastrophe. But rather than condemn them for negligence and permit their claims to be appropriately devalued, we applaud them for "prudence" and let government action be bound by commitments to sustain their destructive and ridiculous claims. You don't counter that sort of villainy with technocratic arguments about liquidity traps. You point out that the motherfuckers who are calling themselves prudent, who are blocking both writedowns and government action that might risk inflation, are hypocrites and thieves. You state clearly that their claims are illegitimate and will be written down one way or another, unless we can generate sufficient growth to ratify them ex post, which would require claimants to behave less like indignant creditors and more like constructive equityholders. It is not technocratic economists who will win the day and pull us out of our cul-de-sac, but angry Irishmen and Spaniards who challenge, on moral terms, the right of German bankers to impose vast deadweight costs on current activity because they lent greedily into what might easily have been recognized as a property and credit bubble.

But to speak up for technocratic economists, the problem issue is that to effect political change you need both populist anger and also some kind of technically workable program. We need people to be angry, and we need moralistic challenges, but then we need ideas from Barry Eichengreen.

A European-Style Fiscal Crisis Is Impossible in the United States of America

(cc photo by LateNightTaskForce)

Lori Montgomery and Brady Dennis write of the Simpson-Bowles Commission that "members from both parties set aside ideological orthodoxy at least briefly, sparking hope that their work could ignite a serious effort to reduce government debt and spare the nation from a European-style fiscal crisis."

Leaving aside the fallacy of forgetting that the church of deficit reduction is also an ideological orthodoxy, it reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of the issues. The government of Ireland can run out of Euros—they make Euros in Frankfurt. And the government of Peru can run out of dollars—they make dollars in Washington. But the government of the United States can't run out of dollars. The problem we could find ourselves with is the problem of inflation. Problematic inflation is a genuinely problematic thing, but it's a strange thing to worry about at the moment when inflation's been running unusually low for years. Our current problem is that the total volume of nominal spending is way too low, which means that as a country we're producing much less than we could be.

The Fallacy of Private Knowledge

This passage from Matt Bai illustrates a lot of what I think is wrong with conventional reportorial methods:

The body of Mr. Obama's writing and experiences before he became a presidential candidate would suggest that he is instinctively pragmatic, typical of an emerging generation that sees all political dogma – be it '60s liberalism or '80s conservatism – as anachronistic. Privately, Mr. Obama has described himself, at times, as essentially a Blue Dog Democrat, referring to the shrinking caucus of fiscally conservative members of the party.

Obama is secretly a Blue Dog! But without breaking any confidences, I can tell you that it's also true that Obama has privately described himself at times as a liberal frustrated with the timidity of more moderate members of the party. Because guess what: Barack Obama is a politician trying to assemble a broad base of support. The idea that his "private" words and deeds reveal his "real" approach is a tempting conceit, but it doesn't really make sense. The real Obama is the public Obama and that Obama's approach to his job reveals an ideology that's similar to your average Senate Democrat. He's like Patty Murray, but much more famous.

Innovations in Nigerian Spam

I'm a big believer in the United Nations, international law, and other efforts to institutional global cooperation. Today I learn that it's finally paying off:

United Nations Development Programme

United Nations House

Plot 617/618, Diplomatic Zone,

Central Area District, Garki,

Abuja, Nigeria.

Compensation Ref Number: UN277360NG

This is to officially notify you that you have been selected as one of the few beneficiary of 2010 United Nations 65th anniversary Compensation by random Email Search System(ESS). Your email id was lucky to be picked among the ten thousand emails that was selected worldwide by UN, you have been compensated with $200,000.00USD by United Nations as a sign to help the less privilege worldwide. to enmark the suecessful United Nations 65th Anniversary Celebration we have decided to give ten thousand people around the world compensation funds as a sign of reducing the global economy and financial meltdown around the world.

I just wonder why they give this thing an Abuja address? Seems like a total giveaway. Why not pretend to be in Geneva, a city renowned for its international institutions and shady banks?

The Balance of Power

(cc photo by kevindooley)

Something that I think is missing in a lot of recent commentary on the Obama administration's negotiating strategy is the key role, as ever, of moderate legislators.

The administration's rational fear about a hardball approach to any issue is the inevitable cavalcade of whining from Evan Bayh, Joe Lieberman, Blanche Lincoln, unnamed Blue Dog House members, etc. Should the administration fear Evan Bayh? Maybe they should. After all, the very next step is John Boehner talking about how the only thing bipartisan about this administration is opposition to its agenda. What you have is a situation in which the very most superficial observer of politics—and keep in mind that swing voters observe politics in a manner that's far more superficial than you can imagine—sees that on the one hand is the President and some liberal Democrats and on the other hand is the entire Republican Party plus many members of the Democratic Party. Now if you're a Democratic member of congress from an even slightly Republican-leaning district or state you need to ask yourself "am I the kind of Democrat who wants to be on the leftwing side of intraparty divides?" Many of them will say "no, I don't" and now to the superficial observer the White House's position has shifted even further to the left.

That's the bouncing ball of legislative doom. Of course the administration's preferred alternative doesn't much work either.

But this is a problem of structural asymmetries in American politics. I'm very skeptical that ideological self-identification polls tell us anything about people's views on policy, but they tell us a lot about self-image and that matters. There are many more people in America who are proud to think of themselves as "conservatives who side with conservatives against moderates" than there are people who are proud to think of themselves as "liberals who side with liberals against moderates." What's more, rich people have much more voice in the political system than poor people; businesses have more voice than labor unions; old people have more voice than young people; Fox has a bigger primetime audience than MSNBC; conservative talk radio has a (much) bigger audience than liberal talk radio; etc.

You guys know all that already. But people sometimes forget it when talking about the details. The point, however, is that it's superficial to believe there's any set of tactical approach to legislative bargaining that can wave all this away. If we were looking forward to the inauguration of Senator Bill Halter or Senator Joe Sestak, things might be different. Or if we were talking about how Representative Alan Grayson and Senator Russ Feingold pulled out gutty wins in a terrible political climate, things might look different. But progressives simply haven't built the volume of institutional power—in the White House or anyplace else—necessary to get the political system to do what we want.

Meanwhile, Scott Brown "is one of the most popular Senators in the country, with 53% of voters approving of his job performance and only 29% disapproving."

Health Care in the 1990s

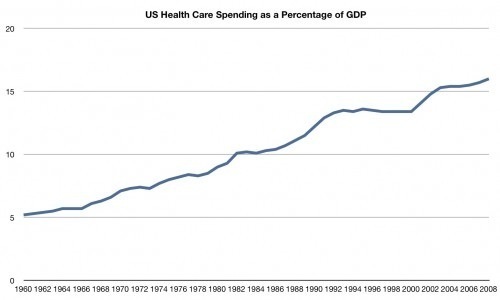

Aaron Carroll gives us an elegant chart of US healthcare spending as a share of GDP over time:

The really striking thing here is the 1990s. That's the HMO era. But it's also an era in which just had rapid economic growth in other sectors. It's important to recall that these X:GDP ratios are all ratios with denominators. The years 2008-2009 will show an explosion in health care spending as a percent of GDP largely because when aggregate demand collapses across the board the health care sector ends up disproportionately insulated from the shock. Conversely, if incomes grow rapidly thanks to some positive shock, healthy people tend not to go out and say "honey, we're rich—let's go get some medical tests," they buy TVs or they redo the kitchen.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers