Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2477

December 7, 2010

Stiglitz's Principles for Deficit Reduction

Internal Revenue Service Building (cc photo by scotteric)

Via Mike Konczal, some "Principles and Guidelines for Deficit Reduction" (PDF) from Joe Stiglitz. These seven points aren't a "plan" or an effort to draw up a politically feasible roadmap, but I think they are a pretty smart way to think about the big picture:

1. Public investments that increase tax revenues by more than enough to pay back the principle plus interest reduce long-run deficits.

2. It is better to tax bad things (like pollution) than good things (like work).

3. Economic sustainability requires environmental sustainability. The polluter pay principle—making polluters pay for the costs they impose on others—is good both for efficiency and for equity.

4. Eliminating corporate welfare is good both for efficiency and for equity.

5. Given the increases in inequality and poverty and given the inequitable nature of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts, the incidence of any tax increases should be progressive, and there should be no increases in the tax burden on the poorest Americans.

6. Eliminating give-aways of public-owned assets is an efficient and fair way of reducing deficits.

7. Eliminating distortions in tax and expenditure policies —with appropriate compensatory policies for lower and middle income Americans—can be an efficient way of reducing the deficits. Even if overall such tax expenditures are regressive, given the dire straits that so many poor and middle class Americans are in, eliminating those tax expenditures without appropriate compensation (e.g. in the reduction in tax rates on lower and middle income Americans) would be wrong.

This all seems about right to me, though of course there's substantial ambiguity around the meaning of the term "middle class" and tension between (3) and (7) if you try to give super-strong readings of both. But I'd like to see much more creativity in our thinking about potential revenue sources. A modest but meaningful contribution could be made by the alcohol industry, there's the carbon pollution issue obviously, and a host of other odd giveaways of the national commons that can and should be brought to an end.

The Trouble With Fiscal Stimulus, Part Zwei

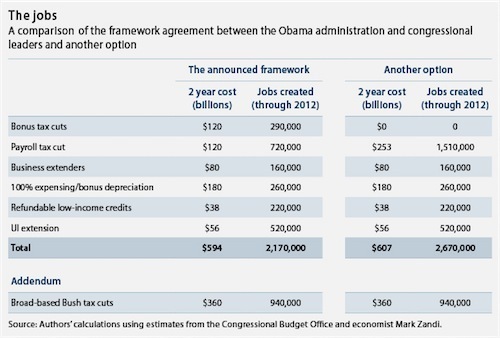

I think this tax deal illustrates what I was getting at in my post on the trouble with fiscal stimulus. If you look at this deal very literally, Republicans were asking for some measures that Democrats regard as only very very very modestly stimulative and in exchange for giving it to them Barack Obama got them to agree to some measures that Democrats regard as substantially more stimulative. And stimulus, say progressives, should be the order of the day. Under the circumstances, progressives should be jumping for joy!

But of course nobody on the left is actually jumping for joy. Instead in the words of my colleagues Michael Ettlinger and Michael Linden we're at best saying that "[i]t is, however, unfortunate that these jobs have to come from an agreement that is a balance between large, unneeded, bonus tax breaks for the wealthiest Americans and the needed continuation of unemployment benefits, middle-class tax relief, and additional help for the economy for the rest of us."

At worst we're where David Dayen is, already looking forward to the day when the hole in the budget blown by the Bush tax cuts becomes rhetorical justification for spending cuts that undue the stimulative impact of the good ideas in here:

In a world where this tax cut-heavy stimulus goes into place, [moderate Democrats are] likely to whine and argue for major spending cuts to offset the hit to the deficit. In other words, I doubt you get $300 billion in stimulus in the coming year, when all is said and done. In fact, I'd expect far less than that.

Clearly the larger issue here is that nobody really thinks you should in fact take this deal super-literally. If the meaning of a compromise that ends in a two-year extension of the high-end Bush tax cuts was really that the parties agreed to phase the tax cuts out, then this would be a great deal. But clearly Republicans have agreed to nothing of the sort. Instead, they've just agreed to re-stage this fight in two years' time. And while the deal will cause the national debt to grow, the deal doesn't include an agreement on raising the debt limit. So another standoff and more concessions are right around the corner.

But all these kind of considerations seem to me to be endemic to the concept of discretionary fiscal stimulus in a country that features large disagreements about economic policy. There needs to be stimulus, you say? Well obviously the tendency will be for actors to try to cram policy measures they think have other good benefits (high speed rail, tax cuts for the rich) into the stimulus bargain. But that undermines the political credibility of the bargaining process, tends to sap support for the overall package, and to land you with chronically too-small fiscal measures. You may say "that's all politics, not economics" but a theory of discretionary fiscal stimulus as a tool of macroeconomic stabilization necessarily needs to be a political theory. And in America, I think that means going forward to the next recession that it means more work on automatic fiscal stabilizers, more thinking about making "unorthodox" monetary policy rule-based, and less optimism about the practical ability of discretionary fiscal policy to deliver the goods.

Democrats and Low-Income Whites

Lane Kenworthy has an excellent post up at the Monkey Cage building on Larry Bartels' research and looking at the question of why low-income white voters don't show more affection for Democratic presidential candidates. You really must read the whole thing for yourself, but this one chart is provocative enough that it should entice you in:

The point here is just to attend to the basic stability of the dynamic as well as to the fact that contrary to boatloads of conventional wisdom, the Clinton/Gore/Kerry era Democrats did better with this demographic than has been the postwar norm.

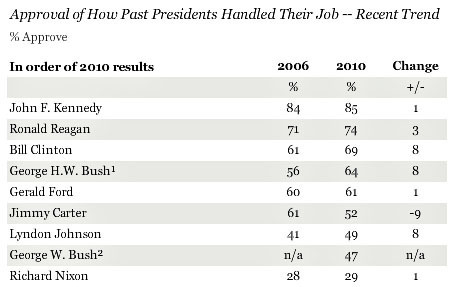

Retroactive Ranking of JFK

Via Kevin Drum, Gallup asks America to look back at recent presidents:

The high marks given to George HW Bush are interesting. The dude left office after getting a pathetic 37 percent of the vote, shattering the once-dominant Reagan coalition, and was immediately repudiated by his party's base. And yet, I guess I agree with the American people—he did a decent job of things.

The sky-high ratings for JFK, while not at all surprising, are a reminder of a kind of fascinating anomaly in how we think of American history. If you look at the Kennedy/Johnson administration as a single unit you have the following:

1. A hugely successful progressive agenda that utterly and enduringly changed American society for the better. That's the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Act, it's Medicare, it's Medicaid, and it's also the oft-overlooked Elementary and Secondary Education Act.

2. A disastrous war in Vietnam that killed far, far, far more people than the misadventure in Iraq plus some serious violations of civil liberties.

3. A ton of smaller-bore lefty stuff that wasn't popular and got rolled back.

It's a bit hard to know what one should say about this JFK/LBJ record and there's no particular reason to think that Kennedy and Johnson had any substantial disagreements about it. But since Kennedy was murdered, it's possible to kind of fudge the history and create a mythic Kennedy figure who's associated with all the parts of Sixties Liberalism that people like, cleansed of all the other stuff.

Plenty of Hypocrisy to Go Around

Stan Collender finds himself blown away by Republican hypocrisy:

After making the budget deficit not just a campaign issue but the campaign issue of 2010, one of the very first legislative things the Republicans in Congress will do after the election is agree to a tax cut and extension of unemployment benefits (and god knows what else) that will…wait for it…increase the deficit. The two-year increase in the deficit because of the deal will be greater than the stimulus bill the GOP railed against during the election.

All very true. But there's actually plenty of this sort of weirdness to go around. Recall that one thing that made the Affordable Care Act a much harder sell in congress than the 2003 Medicare expansion is that 2003 Medicare expansion was financed with debt, whereas the ACA reduces the deficit thanks to a number of politically controversial tax hikes and Medicare cuts. But it was the very same members of the Democratic Party—both in the White House and on the Hill—who insisted ACA couldn't increase the deficit by one iota who were totally unwilling to take a strong anti-deficit line on the tax cut expiration issue.

This is particularly egregious because while the long-run deficit reducing potential of ACA is part of the merits of the plan, the short-term deficit neutrality of it has no real policy rationale. Indeed, the deficit neutrality within the ten-year CBO window was achieved in large part simply by not ramping up the spending until 2014. Had Democrats been willing to increase the short-term deficit by having spending kick-in sooner, they'd have preserved the beneficial impact on the long-term deficit, delivered some concrete benefits to people in time for at least the 2012 election, and stimulated the still-weak economy. But they didn't, out of some kind of misguided substantive or political concern about the short-term deficit—concern they happily kicked away in order to forge this tax cut / UI deal.

Taibbi vs TAP

Matt Taibbi explains what's wrong with American punditry:

Bai is one of those guys — there are hundreds of them in this business — who poses as a wonky, Democrat-leaning "centrist" pundit and then makes a career out of drubbing "unrealistic" liberals and progressives with cartoonish Jane Fonda and Hugo Chavez caricatures. This career path is so well-worn in our business, it's like a Great Silk Road of pseudoleft punditry. First step: graduate Harvard or Columbia, buy some clothes at Urban Outfitters, shore up your socially liberal cred by marching in a gay rights rally or something, then get a job at some place like the American Prospect. Then once you're in, spend a few years writing wonky editorials gently chiding Jane Fonda liberals for failing to grasp the obvious wisdom of the WTC or whatever Bob Rubin/Pete Peterson Foundation deficit-reduction horseshit the Democratic Party chiefs happen to be pimping at the time. Once you've got that down, you just sit tight and wait for the New York Times or the Washington Post to call. It won't be long.

I appreciate what Taibbi is getting at in the piece overall, but not only is this a terrible description of The American Prospect, but as Adam Serwer Matt Bai's actual resumé includes a stint at Rolling Stone and zero stints at TAP. Meanwhile, though I think it's safe to say that Taibbi is somewhat to the left of the TAP alumni of the world it seems to me that a hypothetical universe in which Bob Kuttner, Harold Meyerson, Josh Marshall, Jons Cohn & Chait, Ezra Klein, Dana Goldstein, and myself dominated the public debate would be one that's considerably more congenial to Taibbi's policy preferences than is the actual world.

Anyways, I hesitate to say any more about this because I'm still eagerly awaiting my own call from The New York Times.

The Tax Deal

I've been on a bunch of planes, but catching up on my blog and email reading the progressive wonk consensus seems to be that the tax cut deal is . . . not as bad as people feared it would be based on what was happening the previous week. And I totally agree, though that's largely a case of expectations management so I'm not going to break out the flowers.

What I will say, though, is that this has partially set my mind at ease about the prospects of a GOP strategy of economic sabotage. The tax policy the right wants, though in general bad for the country, is not bad for short-term economic performance. And the concessions they were willing to give Obama in exchange for boosting the incomes of rich people are expansionary in the short-term. So the terrain here exists well within the range of "normal" politics where conservatives want lower taxes on rich people. This is kind of nutty in my view, but it's a deeply held article of faith on the right and not some ad hoc effort to sink the economy or anything.

In a non-optimistic vein, though, this is really kind of sad statement on where Washington is at the moment. What you can say in favor of this deal is that it is a kind of expansionary fiscal policy. But if expansionary fiscal policy is the order of the day, then this is a mighty ineffective way to go about. And if the reason we can't have a real robust jobs program is that deficits are evil, then why on earth is it that we need huge deficit-expanding tax cuts for the children of the hyper-wealthy?

December 6, 2010

Endgame

Once so close to heaven:

— CAP enters the deficit reduction plan sweepstakes.

— The Orszag roadmap.

— 1919 flashback: Stop immigration or terrorists will get us.

— News from Cancun.

— The Treasury Department's new blog.

— Mäp of metal.

Ich Bin Ein Blogger

I'm on a plane, about to take me to Frankfurt and then on to Berlin where I'll be this week doing some stuff with the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. Blogging, as usual when I travel, will continue but there's always some chance of disruption, non-timeliness, or excessive posting about foreign mass transit systems. Last time I was in Berlin I enjoyed biking around the city, but I gather it's going to be below-freezing this week so that doesn't sound promising.

Do I have Berlin-based readers?

Israel's Bad Iran Forecasting Track-Record

I have this vague sense I've been hearing alarmed Israeli reports about an imminent Iranian nuclear weapon since I was in high school, and today Justin Elliott runs it all down in Salon:

According to various Israeli government predictions over the years, Iran was going to have a bomb by the mid-90s — or 1998, 1999, 2000, 2004, 2005, and finally 2010. More recent Israeli predictions have put that date at 2011 or 2014.

None of this is to say that Iran will not at some point get a nuclear weapon — though the Iranian government has maintained that its nuclear program is for peaceful purposes. That said, Iran has not fully cooperated with international inspectors. But even assuming that Iran is seeking a nuclear weapon, estimates still vary widely on when it will reach that goal.

To me the moral of this story is not only that intelligence estimates are uncertain, it's that whatever Iran is doing with its nuclear program it hasn't been engaged in a desperate, all-cylinders-firing, this-is-our-top-priority crash program of nuclear weapons development. Those worst case estimates come from assuming that's what's going on, and the estimates keep being mistaken. Instead, Iran's quest for more nuclear capabilities should be seen in the context of a state that's trying to do many different things and whose priorities shift over time. Something people always need to consider about military attacks on Iran is not only what damage they might do to Iranian nuclear research, but also what policy shifts they might induce in Iran in terms of increasing emphasis on nuclear activities.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers