Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2479

December 5, 2010

To Defend Everything Is to Defend Nothing

I'm not sure if this will meet Kevin Drum's odd demand that people refrain from making reason-based arguments about terrorism because many people have irrational reactions to violence, but I think there's a strong case to be made against airport-style security at the Washington Monument.

The key issue, I think, is that if you've got an armed man in Washington DC eager and willing to kill and die in a holy war against America, he's not going to just give up and go home simply because we've put metal detectors at the Washington Monument. Maybe he'll shoot up the Pentagon City mall instead. Or maybe the Portrait Gallery. Or a movie theater. Or a crowded bar at happy hour. There are big crowds all across America and attempting to erect impenetrable static security at all of them would be a disaster. So you need to set priorities. And it's clear to me why it makes sense for the White House to have much higher security than a movie theater. And it also makes sense for Capitol and the Supreme Court to have very high security. A lesser level of security would be appropriate for the various federal agency buildings around DC, but still higher security than we have at the movie theater.

But would the impact—in terms of lives lost, in terms of the national psyche, or in terms of the orderly conduct of everyday life—of an attack on the Washington Monument really be significantly different than an attack on a movie theater? I don't really see it.

The point is that there are just way, way, way, way, way too many "soft targets" all across the country to harden them all in the way being contemplated for the Washington Monument. We need to focus static security on a smaller set of high-priority locations. For the rest we're going to need to rely on proactive security via law enforcement and intelligence.

Things to Disagree About

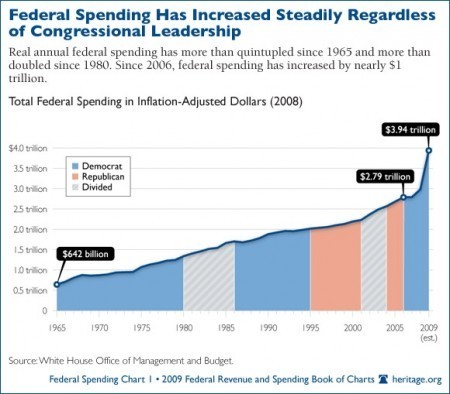

David Boaz observes that inflation-adjusted federal spending tends to increase steadily even as the political winds fluctuate:

But the bottom line is: If we have two parties for a reason, because they believe in different things, why don't we some real differences in the growth of federal spending?

Is this really such a hard question? It's just that the disagreements between the parties must be about something else than the fake fight over "spending." For example, "what should we spend money on?" Or, "how should the burden of taxes be distributed?"

But on the spending front, let's note this. Barack Obama proposed a deficit-financed extension of some of the Bush tax cuts. Congressional Republicans calculated, accurately, that Obama was so committed to the goal of extending some of the Bush tax cuts that they could hold this goal hostage and force concessions on other issues. This would have been a golden opportunity, for example, to say they would only vote for Obama's precious tax cuts if Obama agreed to offsetting spending cuts. But they didn't do that. Instead they said they would block Obama's tax cuts unless Obama agreed to additional "rich people only" tax cuts. That's a real, meaningful disagreement, one that's typical of our times, but it's not a disagreement about the quantity of spending.

The Discontent Baseline

I asked this on Twitter yesterday, but I think it's an important issue. At lunch with a coworker last week talking over the "pay freeze" nonsense and the bargaining over the Bush tax cuts, I was a bit ready to throw the towel in over Barack Obama. And I retract none of my psychic derision of these latest moves. I'll just quote my colleague Adam Hersh, "No Time to Dawdle: Latest Jobs Numbers Confirm Immediate Priority for Job Creation, Not Deficit Reduction". Disaster. Oy.

That said, in analytic terms it's worth trying to say what your discontent baseline is. Barack Obama has assembled an insufficient track record of progressive achievements compared to Bill Clinton? Doubtful. To Jimmy Carter? No. To John F Kennedy? Also to. To Lyndon Johnson, clearly yes, but the record on wars and civil liberties here is much worse. So is Barack Obama, for all his failings, the greatest progressive president in 70 years? That sounds like very high praise to me.

Now in political advocacy terms it doesn't make sense to say "well, I'll forgive a misguided pivot to austerity because the Vietnam War was a bigger mistake." Nor does it make sense to say "I don't care about claimed assassination powers because the internment of the Japanese was a bigger curtailment of civil liberties." Nor does it make sense to say, "I won't complain about cutting a deal with Pharma to get a major expansion of the welfare state because FDR cut a deal with white supremacists to get his." You need to stand up for what you believe in in politics and complain when elected officials don't do the right thing.

But as an analyst you do need to obtain some kind of perspective.

Class, Math, and Social Security

Paul Krugman comments on DC's endless fascination with Social Security cuts:

When medical expenses are big, they're big; even the very affluent are grateful when Medicare pays the bills for their mother-in-laws bypass or dialysis. The importance of Medicare, in short, is obvious to all but the very rich.

Social Security, by contrast, is something that matters enormously to the bottom half of the income distribution, but no so much to people in the 250K-plus club. A 30 percent cut in benefits would represent disaster for tens of millions of Americans, but a barely noticeable inconvenience for VSPs and everyone they know. A rise in the retirement age would be a vast hardship for people who do manual labor, but if anything a gift to VSPs, who don't want to step aside in any case. And so on down the line.

So going after Social Security is a way to seem tough and serious — but entirely at the expense of people you don't know.

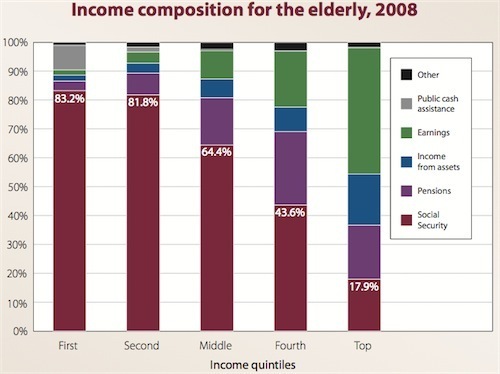

Here's a chart from the Our Fiscal Future report that makes the point:

Even though Social Security is only a very mildly redistributive program, inequality of wealth is such that it's a vital element of the bottom 60 percent's living standards but kind of small beer to the top twenty percent. But I would say the other thing here on the Medicare / Social Security contrast is that Medicare isn't just a subsidy program for old people. It's also a subsidy program for doctors, nurses, hospital administrators, pharmaceutical executives, etc. Those people have lobbyists, many of their professions are well-respected, and many members of the political/media elite have siblings, cousins, college buddies, and even spouses who work in those fields.

The tragedy is that this very same factor that makes it harder to cut Medicare is also why cutting Social Security is a much worse idea. Our health care sector is low productivity mess and there are a lot of health-improving things a low-income senior can buy with Social Security money but can't buy with Medicare. Healthy food, a gym membership, home-repair, etc.

But there is a flipside to Krugman's point here, namely that you could in fact trim Social Security benefits for wealthier Americans without causing them much harm. Conversely, if it were possible to address Social Security's adequacy problem by boosting benefits at the bottom end you'd do an enormous amount to improve living standards. It's kind of absurd that such a large share of federal spending goes to income support for the elderly and yet 10 percent of our seniors live below the poverty line.

December 4, 2010

Third Rail

Brian Beutler reports:

"The third rail is not the third rail anymore," Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI), the incoming House Budget chairman, told reporters at a Christian Science Monitor breakfast roundtable with reporters yesterday. "The political weaponization of entitlement reform is no longer as potent as it used to be, and the best evidence is this last election."

Ryan and several other influential Republicans have found new confidence in the idea that the public would support entitlement cuts. Several candidates, Ryan said, won elections in tough districts on policy platforms modeled after his controversial — and conservative — Roadmap for America's Future would would privatize social security and turn Medicare into a voucher system.

Here's the Senate GOP caucus complaining that Democrats want to spend too little on Medicare:

I'm not sure which election Ryan was watching.

Escalator Repair Pathologies

I've often wondered why escalators are so often broken in the DC Metro system. Unsuck DC Metro has a fascinating post indicating that the "pick" system used to allocate mechanics deserves a share of the blame:

The source said it's very common for someone with seniority to bid on escalators they know to be well maintained so they can slide and and not do anything for the six months it's under their "care."

"They can coast for a while," the source said. "Then when problems start, they can move on," leaving an ailing escalator under the supervision of someone with less experience.

This way of doing things, the source said, "destroys the incentive" of the younger workers who know that if they do a good job, their escalators will be taken away by someone with more seniority.

It seems like the solution here would be to not let people switch on a fixed schedule. You stick with a given escalator until you retire or quit or get fired. Then when a slot opens up, people could be given the opportunity to switch to it with preference according to seniority.

Incidentally, stories like this are why I'm unimpressed by both the pro and con studies about whether or not public sector workers are "overpaid." WMATA-area taxpayers are getting inadequate value for our escalator-related tax dollar. But the solution here isn't to pay the people less and establish a new equilibrium where the job's done badly, but at least it's done cheaply. The issue is that the job needs to be done properly. The absolute worst thing about the American public sector is the prevalence of non-cash compensation in the form of quality-sapping work rules. The money is incidental.

Pulling Back The Curtain on Human Behavior

Hot new sex research that I'll link to if only for the SEO benefits:

In a first of its kind study, a team of investigators led by Justin Garcia, a SUNY Doctoral Diversity Fellow in the laboratory of evolutionary anthropology and health at Binghamton University, State University of New York, has taken a broad look at sexual behavior, matching choices with genes and has come up with a new theory on what makes humans 'tick' when it comes to sexual activity. The biggest culprit seems to be the dopamine receptor D4 polymorphism, or DRD4 gene. Already linked to sensation-seeking behavior such as alcohol use and gambling, DRD4 is known to influence the brain's chemistry and subsequently, an individual's behavior. [...]

"What we found was that individuals with a certain variant of the DRD4 gene were more likely to have a history of uncommitted sex, including one-night stands and acts of infidelity," said Garcia. "The motivation seems to stem from a system of pleasure and reward, which is where the release of dopamine comes in. In cases of uncommitted sex, the risks are high, the rewards substantial and the motivation variable — all elements that ensure a dopamine 'rush.'"

This kind of research is in its infancy, life is complicated, etc., so I wouldn't take this particular finding to the bank. But clearly our knowledge of the genetic correlates of behavior is increasing and will only continue to increase in the future. The implications of this for public policy and society seem to me like they'll be pretty profound.

People sometimes seem to think that you could forestall a Gattaca-esque scenario of genetic transparency through privacy laws. But it seems to me that you'd actually need to go stronger, and not only guarantee the right to not have your genetic information disclosed. To prevent the emergence of a near-universal disclosure equilibrium in a world of cheap genetic profiling over the long run, you'd need to ban voluntary disclosure. The mere fact that you don't want a potential partner to know your DRD4 profile will tell her all she needs to know about you.

Who Do You Trust

I think almost all political polls are overrated in terms of their relevance, but Gallup's efforts to gauge the popularity of different occupational groups are underrated:

The very high ratings given to military officers is hugely important in understanding the politics of the war in Afghanistan. And the very high ratings given to health care providers is hugely important in understanding the politics of health care costs. Any given cut in spending might be a trimming of fat, or else it might lead to a major reduction in the availability of useful health care services. And in a standoff between a member of congress and a doctor or nurse over which it is, people are highly inclined to believe the member of congress is lying.

Comments?

Belle Waring asks:

Question of the day: is the unremitting, permanent badness of Matthew Yglesias' comments the result of intentional sabotage, or can it be chalked up to his policy of utterly ignoring them at all times? I favor the former explanation, because he's influential enough that I can imagine some testy Republican or two taking it on as a volunteer project to wreck it up constantly. There was never a time when they were good, either, even in the early days.

I would simply deny that "ignoring" takes place. I read the comments most days, and even chime in from time to time. But it's hard to engage too thoroughly when they're so sucky. The primary interpreative technique that takes place in the section is "let's willfully misread what Matt's saying so as to make it something I strongly disagree with." It's not very fun. But I actually think things have gotten a lot better since the latest update to the software. The ability to do nested threads means some interesting chains of thought can emerge and I would encourage more people to try to participate constructively and shift the norms away from the soullite & warstler model.

The Limited Relevance of the Pill

(cc photo by jessamy.n)

Kay Steiger observes that for all the hype, "the pill" is hardly the be-all and end-all of birth control options:

First of all, while the pill (which includes it's alternative methods of the Nuvaring and the Depo-Provera shot) is very popular, it's only barely the most popular form of birth control. According to Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive health think tank, 28 percent of women choose the pill as their primary form of birth control. It's followed closely by tubular sterilization (27.1 percent), and more distantly followed by the condom (16.1 percent), male vasectomies (9.9 percent, and intrauterine devices, or IUDs (5.5 percent). Incidentally, IUDs, an effective form of birth control, come with hefty upfront costs that are rarely covered by insurance. It's possible IUDs would be more popular if they were more affordable.

In other words, while the pill has changed the world, it's more that the pill was the first such technology to help women take control over their reproductive lives. Other technologies have stepped in to offer a diverse set of choices for women, even if there are few choices for men — something Grigoriadis, to her credit, takes time to point out.

The general lack of insurance coverage of birth control is both ridiculous and a good example of the limits of looking at health care services primarily through an "insurance" paradigm. Universal free birth control would be a social service well-worth providing, as would it's natural complement of universal preschool.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers