Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2485

November 29, 2010

War and Speech

Dahlia Lithwick did a great piece over the weekend about wartime restrictions on free speech and how we haven't really had many even at a time when civil liberties have been curtailed in many other ways:

In other words, when it comes to antiwar speech we may have reached something like perfect—though that seems the wrong adjective somehow—equilibrium: Americans don't much care to protest. The government cares very little if we do. And the courts don't much care about what happens either way. That we find ourselves in an open-ended war on "terror" that will never end but it never becomes quite real to us suggests that maybe the antiwar movement won't really be taken seriously in the courts until they start to protest in video game format.

I wonder if Julian Assange might be just the man to break down this equilibrium. Currently the rule is that it's illegal to be the guy with legal access to classified information who passes it on to outsiders, but once you receive the leak you're free to do what you want with it. But for the past 24 hours I've seen a lot of outrage directed not just at Bradley Manning but also at Assange and WikiLeaks. Operationalizing that anti-Assange outrage would, it seems to me, necessarily entail challenging our current understanding of the First Amendment. Representative Peter King's suggestion that we designate WikiLeaks as a foreign terrorist organization is in part grandstanding and in part an effort to devise a way to begin restricting freedom of the press.

Why DNA?

That the US gathers information about the foreigners it deals with isn't surprising, but as Spencer Ackerman points out WikiLeaked information about US government interest in acquiring DNA samples of sundry foreign officials is a bit harder to explain.

The problem here is that Ackerman's not a Star Trek fan. If he were, he would clearly recognize this as inspired by the Dominion's plan to infiltrate the Alpha Quadrant by replacing key leaders with shapeshifter impersonators. We obviously don't have access to shapeshifters, so the only path available to us is going to be cloning replacement leaders. By blowing the whistle on this program, WikiLeaks is in effect operating as a force multiplier. Now foreign governments are set to be wracked by fear and paranoia about possible clone-replacement without us needing to go through the difficult steps of actually growing the clones. After all, given America's deficiencies in foreign language instruction, all the cloning in the world isn't going to let us create tolerable copies—the best we can do is spread fear of copies.

Transparency and Diplomacy

It's easy to see how an inability to keep secrets can hamper diplomacy. But it's also worth considering the ways in which the ability to keep secrets can hinder diplomacy. Consider Iran. Suppose Ayatollah Khameini has a spiritual awakening and decides he doesn't want nuclear weapons. But he thinks that for Iran to sign away its rights under the Non-Proliferation Treaty would be a national humiliation too far. Why should Iran be treated any differently than Germany or South Korea?

Obviously it would be in the interests of the West to strike a bargain around these terms. But equally obviously, if the Iranian government were to propose these terms there'd immediately be a problem of credibility. The West would insist on credible, verifiable disarmament which is a different thing and might require steps that Iran won't agree to. In part, inability to strike this bargain is part of the price Iran needs to pay for past bad acts. But in part it's a price Iran is paying precisely because Iran can keep secrets. If WikiLeaks were constantly publishing Iranian diplomatic cables, it would in some ways be easier to do a bargain. Or on the flipside you sometimes hear that the United States can or should offer "security guarantees" as part of a deal. Actual guarantees from the US should be quite valuable. But talk is cheap. And the fact that we're able to keep secrets tends to turn our potentially valuable guarantees into cheap talk.

Indeed, as John Ikenberry has written in some ways it's the degraded secrecy capabilities of democracies that makes it possible for us to collaborate so intensively. One reason the peaceful US/Canadian relationship works is that clearly in practice there'd be no way to mobilize the country for an invasion without it leaking. The fact that there are no such leaks gives the Canadians confidence that we're not secretly planning to invade, which means they don't spend their time plotting for an asymmetric war with the United States. And since they're not doing that, we're not constantly worried about Canadian terrorist financing and WMD programs and drawing up plans to invade.

Libertarian Tax Policy

Cato's Daniel Mitchell argues: "Swiss voters, like voters in Washington state earlier this month, understood that giving politicians more money is never a solution for any problem."

Never? Any? No "we need to buy a bunch of tanks to stop Hitler" exemption? Nothing?

Deadweight Loss of Liquor License Restrictions

Street noise is a very real issue in large swathes of Manhattan and I think it's perfectly understandable that people prefer not to have lively nightlife scenes located directly outside their windows. So when I read Sarah Laskow's long and excellent account of liquor license battles in the East Village, I'm not-unsympathetic to the incumbent residents' concerns. But as she observes at the end, there's a real cost to this attitude:

At the meeting with Kao, the locals gave him the same reason for opposing him that they had given Warren, when he wanted to open a burger bar in the space: according to the current license, the only type of business that should be selling liquor at 200 Ave. A is a bookshop. With rent set at $10,000 in the East Village Party District, that's as unlikely as it sounds.

The broader issue, as she explains, is that cities are driven by agglomeration:

Academics have a word for what the neighborhood has become: a nightscape. Bars and restaurants were once peripheral to the main drag's primary economic drivers: supermarkets, coffeehouses, boutique shops, record stores. But in post-industrial cities, nightlife has grown into an industry in its own right. As in any industry, shop owners tend to cluster. A century ago, that meant the creation of a Garment District. Now it means the creation of a Party District.

Basically the East Village really "wants" to be full of nightlife establishments just like Qiaotou, China wants button factories. Restricting the creation of new button factories in Qiatou will help incumbent button makers (and alleviate neighborhood concerns about factory smoot) but it's hard to call a bar scene into existence that way. Similarly, making it hard to open a new bar in the East Village isn't going to create a button factory. It's going to create an underutilized space. That means somewhat more unemployment in the city, somewhat less tax revenue in the city, and thus at the margin higher tax rates and fewer social services for everyone.

Meanwhile, as a policy analyst living in a different city the right way to look at the neighborhood concerns is this. Will another bar on the block make living on that block worse? I have no reason to doubt it. But it's not like there's some excessive quantity of affordable housing in Manhattan. If a given block becomes less desirable to live on, that just means someone else will live there. In equilibrium, we're looking at lower housing costs and higher employment rates.

The bigger question here is about levels of governance. Insofar as you empower residents of my building in DC to make the decision, we will attempt to regulate the food service establishments on our block so as to minimize late-night noise. After all, the service sector jobs lost in the process aren't the jobs that we do while as homeowners we bear the losses of reduced property values on the block. And to simply disempower us, as a block, would be arbitrary and unfair. But empowering each and every block leads to highly inefficient outcomes with the bulk of the pain felt by low-income people and there's no obvious reason of justice to think this kind of hyper-local empowerment is more legitimate than taking a broader view would be.

Medicare and Doctor Availability

Ezra Klein writes about doctors who are curtailing the amount of time they're willing to spend treating Medicare patients:

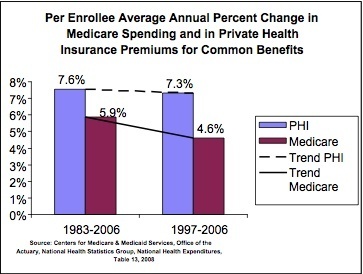

One of the dirty little secrets of the health-care system is that Medicare has done a much better job controlling costs (pdf) than private health insurers.

The problem is that Medicare can't control costs too much better than private insurers or, as you see from the article above, doctors will simply abandon Medicare. In a world where there's only Medicare and Medicare decides to control costs, doctors can either take the pay cut or stop being doctors. And as we see from other countries, lots of people want to be doctors, even if being a doctor doesn't make you particularly wealthy. But in a world where Medicare is just one of many payers and Medicare decides to control costs, doctors can simply stop taking Medicare patients and a lot of legislators will lose their jobs.

I always think this concern is overblown if taken literally. It's true that any particular doctor can refuse to see Medicare patients and instead fill his schedule with the privately insured, but doctors as a whole can't do this. Medicare beneficiaries are too big a slice of the market for the entire doctoring industry to give them up as clients. Instead what you're looking at is that in markets with meaningful competition among health care providers, the most in-demand providers are filling their schedules with the highest-paying customers—i.e., not Medicare beneficiaries. Medicaid has even lower payment rates than Medicare and so we already have a quite robust "lower-tier" of health care providers who take Medicaid patients and a higher tier that doesn't. If Medicare and private payment rates diverge, we could see a more elaborate three-tier system.

Alternatively, Congress could choose to seriously crack down on doctors. They could pass a law next saying that doctors who want to see patients who benefit from tax-subsidized group health insurance plans (i.e., basically all health plans) need to see Medicare patients on equal terms. There could still be a tiny "top tier" of super-exclusive medical boutiques in New York and LA, but basically you'd eliminate the problem here at the cost of pissing off doctors.

The larger point is that there's nothing stopping us from creating a de facto system of national price controls for what we pay to health care providers. There are a lot of reasons why we don't do it, some good and some bad, but the option of "controlling health care costs" by telling the health care industry it needs to start charging prices that are closer to marginal cost will "work" fine. The whole industry is systematically dependent on explicit and implicit government subsidies (direct public spending, tax subsidies, patents, etc.) so there's not some shortage of levers you could apply if you wanted to.

Pay Freeze

I 100 percent understand the politics behind the President getting behind the idea of a freeze in federal civilian pay. If it were the case that political messaging gambits had an appreciable impact on election outcomes, this would be a smart political move. In the real world, however, they don't and the real question is how does this impact the macroeconomy.

The answer, as I understand it, is that relative to other equal-dollar forms of fiscal contraction, this does a relatively small amount of harm. Which is to say that if you implemented a federal civilian pay freeze and used the money saved on job-creating stimulus, that you'd have a good policy idea. So for example you might want to propose a bargain that involved a spending freeze as part of a negotiating process. Instead, following the principle of "if it didn't work the first 20 times let me try it again" the Obama administration seems to have decided that making preemptive compromises will strengthen their hand in some unspecified way down the road.

I'll note once again though that for all the progressive huffing and puffing about rightwing misinformation, one very large challenge we face is that many Democratic Party insiders appear not to believe the New Keynesian diagnosis of the business cycle.

The Left and the Budget

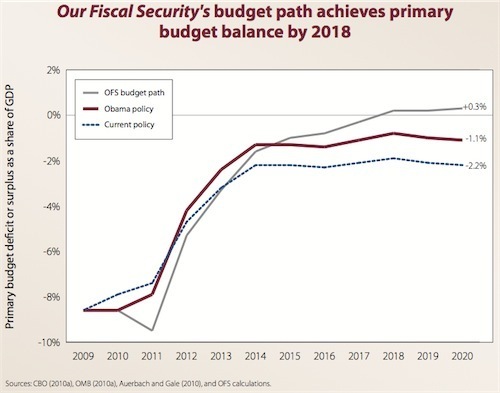

Liberals didn't like the Simpson-Bowles deficit plan largely because neither Simpson nor Bowles is a liberal so their proposal doesn't encapsulate liberal thinking. Today the Our Fiscal Security coalition, comprised of Demos, the Economic Policy Institute, and the Century Foundation have released their fiscal blueprint which shows you would that liberal take would look like.

First and foremost that means explicitly situating the "budget" problem in a broader economic context. You see this two ways. One is the heavy (and appropriate) emphasis in the short term on mobilizing excess capacity to increase growth and decrease unemployment rather than austerity budgeting that will only increase resource-idling. The other is the principle they call No Cost Shifting, namely "Policies that simply shift costs from the federal government to individuals and families may improve the government's balance sheet but may worsen the condition of many Americans, leaving the overall economy no better off." This is really an important point. You could have K-12 public schools start charging $1,000 annual tuition and offer low-income families "school affordability tax credits" to ensure they can send their kids to school. It would be very superficial to look at the consequences of that measure primarily in terms of its impact on public balance sheets. The main point is that you'd be raising marginal tax rates on the poor (as the affordability credit phases out) and transferring resources from parents to non-parents.

At any rate, they show that medium term balance can be achieved basically entirely on the tax and defense sides:

For the longer-term, like all long-term budget plans they need to rely heavily on fairly speculative assertions about health care costs. But I think that if you dig into it, you'll find that OFS offers the least hand-waving on this point of any plan I've yet seen, though that's not to say there's no hand-waving. If you read between the lines of OFS and Rivlin-Domenici you can begin to see the faint outlines of a debate between price controls (OFS) and rationing (Rivlin-Domenici) as a preferred approach to reducing the growth in health care costs.

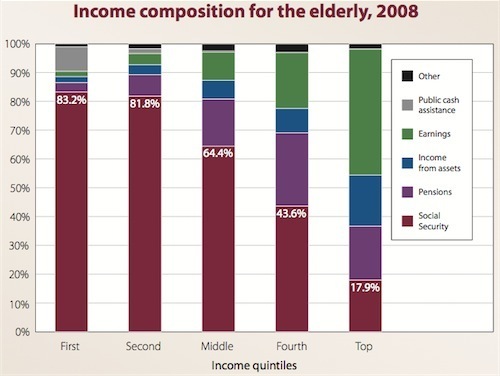

This chart from OFS is an excellent illustration of what the Social Security debate is about:

Note that the bottom 40 percent don't live as long as richer people, so the impact of raising the retirement age is especially regressive.

Long Term Consequences of Leaked Diplomatic Cables

Kevin Drum asks:

[A]ll governments have a legitimate need for a certain amount of secrecy. In particular, embassy officials need to be able to report candidly to their superiors about what's going on in their sphere of responsibility. So what's the most likely consequence of the Wikileaks document dump? That governments around the world realize the error of their ways and become more open about their dealings with the rest of the world? Or that governments around the world — and in particular the United States government — clamp down hard on classified information and restrict its distribution even more than they have in the past?

In part number two, but in part I think we're going to be looking at something even more dastardly than tightly controlled dissemination of information. We're going to be looking at telephone calls! One of the lessons of the Presidential Records Act should be that it's really really hard to force transparency. Basically the main way people have responded to PRA in practice is that folks who you might have emailed with back before they joined the Obama administration now only want to talk on the phone. We'll have more oral briefings via telephone (and face to face), and "candid assessments" will come to even more closely resemble high school gossip.

Whatever you think the bounds are of "legitimate" secrecy (read Henry Farrell on diplomacy and hypocrisy), there's no question that the kind of bid for global hegemony that the United States is currently engaged in requires quite a lot of at least semi-secret goings on. And I don't find it remotely plausible that attacking the logistical basis of the secrecy is going to alter the structural features of US and international politics that drive the bid for hegemony. So there'll be a redoubling of efforts—more phone calls, more compartmentalization, more expenditure of resources on tracking Julian Assange down—and life will go on.

Spain and Bank Runs

Paul Krugman explains why Spain likely neither will nor should leave the Euro:

Should Spain try to break out of this trap by leaving the euro, and re-establishing its own currency? Will it? The answer to both questions is, probably not. Spain would be better off now if it had never adopted the euro — but trying to leave would create a huge banking crisis, as depositors raced to move their money elsewhere. Unless there's a catastrophic bank crisis anyway — which seems plausible for Greece and increasingly possible in Ireland, but unlikely though not impossible for Spain — it's hard to see any Spanish government taking the risk of "de-euroizing."

I suppose one issue is this: Having read this column, if I had a Spanish bank account I'd now be looking for feasible ways to minimize the amount of funds in it. And once everyone starts hedging against a bank run, your bank run is under way.

The larger question posed here is whether it really makes sense to be running separate national banking systems parallel to a single continent-wide monetary authority. A regulatory system that works fine until there's a problem doesn't really work at all.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers