Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2489

November 24, 2010

Small Business Bias

Lydia DePillis has an interesting piece explaining how the new IHOP in Columbia Heights managed to qualify as a small business for the purposes of a small business set-aside rule in the development where it's located. Basically even though common sense says IHOP is a national chain, it's in fact organized as franchises, such that the actual business renting the space is a locally owned small business that subcontracts with national IHOP.

So good for them. But the ability of an IHOP franchise to qualify as a locally owned small business highlights the fact that this distinction is somewhat arbitrary—a person musing that she's like to see more locally owned small businesses in her neighborhood would probably be disappointed to see a McDonald's, franchise ownership structure notwithstanding. And the widespread bias in favor of small businesses in American discourse makes little sense to me. You often hear this in terms of the fact that small businesses account for the bulk of job creation. But that's simply because the small business sector is more unstable. Basically if you look at gross figures you see that small businesses account for most of the new jobs and most of the layoffs. It's neither here nor there.

The other way to look at this is that growth comes primarily from new businesses which are, by definition, small when they start. But the point here is that it's the process of becoming big that creates the growth and it's not clear that pro-small bias actually helps this happen. What's more, with any business you've got some consumer surplus and some producer surplus. With a big business, there's the possibility that unionization can force owners to share a larger slice of the consumer surplus with the workers.

I suspect two things are going on. The main one is a belief that regulatory subsidies to small businesses come mainly at the expense of big businesses. Nobody's going to cry for the owners and managers of large successful firms. But this is an analytical error. The majority of business income goes to salary and benefits not to profits. So the cost is borne primarily by the hypothetical extra employees of disfavored large firms, not by their owners. The other is the idea that small business profits "stay in the community" whereas a big firm vacuums them up to somewhere. This, however, is obsolete. The whole point of having established large nationwide banks is that it's now possible to channel capital from anywhere to anywhere very quickly. The location of the financial input is irrelevant.

I know some commenters here seem to think that since libertarianism is a false doctrine it therefore follows that all instances of government regulation are good. A sounder view is that since wealthy special interests are politically powerful, we should always be on guard against efforts by the politically powerful to enrich themselves at the expense of the public. Local business owners are powerful in local politics, and seem to be gaming the system in a way that's detrimental to working people.

Countries Don't Compete

There are some worthy points in today's Thomas Friedman column, but his concept of international economic competition is dead wrong. He thinks this is a partial explanation for high US unemployment:

Global competition is stiffer. Just think about two of our most elite colleges. When Harvard and Yale were all male, applicants had to compete only against a pool of white males to get in. But when Harvard and Yale admitted women and more minorities, white males had to step up their game. But when the cold war ended, globalization took hold. As Harvard and Yale started to admit more Chinese, Indians, Singaporeans, Poles and Vietnamese, both American men and women had to step up their games to get in. And as the education systems of China, India, Singapore, Poland and Vietnam continue to improve, and more of their cream rises to the top and more of their young people apply to Ivy League schools, it is only going to get more competitive for American men and women at every school.

To stand up for the old New England WASP establishment for a moment, let's note that Harvard's first African-American student graduated in 1870 and Yale's graduated in 1874. But it's of course true that if the quantity of people in the world capable of getting high SAT scores goes up faster than the number of spaces at Harvard and Yale then it will get harder to get into Harvard and Yale. This is a problem that's historically been solved by founding Stanford, but if the rich people of the world collective refuse to launch new institutions of higher education then there's going to be a problem here.

But this has nothing to do with unemployment in the United States. If you look at countries that are doing well economically right now—Germany, Australia, Norway—what you'll see is that these places haven't "out-competed" China, they sell stuff that China imports. Specifically Chinese growth is increasing global demand for natural resources and for Germany's heavy industrial equipment. The competition paradigm implies that if China were struck tomorrow by a horrifying disease that led to its rapid economic collapse, that we'd somehow benefit. In fact, there'd be a global economic disaster.

It would of course be better for America to have a healthier, better-educated population and better infrastructure. But this is true no matter what happens in China or any other country.

Trust in Government

Matt Bai muses:

In this way, the "Don't touch my junk" fiasco raises, yet again, what has become the central theme of Mr. Obama's presidency: America's faltering confidence in the ability of government to make things work. From stimulus spending and the health care law to the federal response to oil in the Gulf of Mexico, Mr. Obama has continually stumbled — blindly, it seems — into some version of the same debate, which is about whether we can trust federal bureaucracies to expand their reach without harming citizens or industry.

That broad-based skepticism of government is, of course, why the Obama Era has also witnessed a broad-based public backlash against unrestrained government surveillance powers, the closure of the Guantanamo Bay detention facility, public demands that Obama cut Medicare benefits more sharply. That's why a ballot initiative to legalize marijuana passed easily in California, and public momentum is growing to get Big Government off our southern borders and let people travel back and forth more easily.

I would say the main story of the Obama years has to do with people's trust in other people. Most Americans are white, most Americans have health insurance, most Americans are native-born citizens, most Americans aren't Muslims, and over the course of the Great Recession most Americans have become more suspicious that they live in a zero-sum world where any effort to improve the condition of other people will come at their expense.

Admission by Lottery

(cc photo by J. Gresham)

Dylan Matthews is quite right that there's a good case to be made that elite schools should do admissions by lottery rather than hand-picking their classes. But he kind of welds together two different ideas. This is the very strong claim:

By virtue of being the kind of students Harvard admits, people who go here already have a huge leg-up in life. A student admitted because of her preternatural brilliance would have been rewarded for that anyway. So, too, for a student with an extraordinary work ethic or an exceptional talent for the arts. Given that these students have so much going for them already, why should Harvard devote its resources to helping them even more?

This is why, as I've said on many occasions, people should not donate money to rich elite American colleges. Their students are the ones least in need of the resources your money can help provide. But Matthews' specific proposal doesn't really get at this issue:

High school seniors would apply to a single admissions body and list their school preferences in order. Schools would set a minimum SAT score and high school GPA so that they do not admit students who truly cannot handle the work, but, otherwise, schools are randomly matched with students who list them as a preference.

Harvard probably has enough sway to launch such a system, but barring that it should set its own minimum threshold and then randomly cull from that vast majority of applicants who meet it. William R. Fitzsimmons '67, Harvard's long-time dean of admissions and financial aid, has said that 80 to 90 percent of Harvard applicants are qualified to be here. Harvard should identify that 80 to 90 percent, and then randomly accept 1600-1700 of them.

A system like that would still maintain the backwards allocation of resources where the richest schools have the best students.

But I think even this weaker version of the proposal would have an important beneficial impact, namely it would make the sorting/selection factor of higher education much more transparent. If "I was smart enough to get into School X" was exactly equivalent to "I got blah blah score on my SAT and then won a lottery" then suddenly School X is under fairly intense pressure to show it's delivering actually educational value. The United States currently spends a lot of money on higher education and young people spend a lot of time getting higher educated, and we're reasonably sure there's some value created by all this, but we have no idea how much and there's almost no competitive pressure on schools to increase value. Randomizing admissions, even with a cut-off point, would change the game in this regard.

Affordability: Resources, Not Money

Probably the biggest thing that trips people up when thinking about countercyclical public policy is a misleading over-emphasis on accounting ledger books as the right measure of what can and can't be afforded. Making sums add up is important, of course, but it's more helpful to start by thinking about real resources. People's time, capital goods, raw materials, etc.

Think about the mayor of a mid-sized city presiding over good economic times. Tax revenues are going up, and demands on social services are relatively low. Suddenly the budgetary picture looks very bright and it seems easy to "afford" longer library hours, more frequent bus service, and tax cuts. This, however, is close to backwards. You can't manufacture librarians or bus drivers. It's when times are good that it's most costly to pull human beings out of whatever else they're doing and have them drive buses. Similarly, it's when people are flush that extra money in their pockets is going to go to enterprises with low marginal utility.

Then along comes the crash and suddenly the budget looks bleak. Now we "can't afford" those extra social services and we need higher taxes. But with household budgets tight, the taxes are much more burdensome than they would have been in good times. And the real social cost of having someone work in a library rather than sit at home unemployed is probably below zero.

What you actually ought to be doing is setting the quantity of social services at some level that makes sense across the business cycle. Then during periods of economic growth, taxes should raise more money than you spend. That way thanks to your stockpile you never need to cut services in the face of a recession and in fact can shower your city with tax cuts during a downturn to families can get by. But of course almost no jurisdiction in America actually does engage in this sort of responsible budgeting, and the Reagan and W Bush administrations took the federal government on a wildly different course. This has bad economic consequences on its own terms, and I also think tends to distort the political dialogue. Since budget deficits are "bad," it's unintuitive to say that bigger deficits will help in a recession. By contrast I think it'd be easy for people to see why a surplus-accumulating government shouldn't try to horde even more money at a time when people are struggling. The reality is that nothing magical happens at zero, and what we "can afford" is ultimately determined by how many resources are available not by accountants.

November 23, 2010

Endgame

Give your reasons:

— 4 October 2006, "In our opinion Twttr, which competes with Google owned Dodgeball for attention, should be the next to go as the company focuses on the basics."

— Winning climate messages combine dire science with a vision for justice.

— Cool kinect stuff.

— All you ever wanted to know about DickFlash.com.

New Robyn "Call Your Girlfriend".

The 2012 Forecast

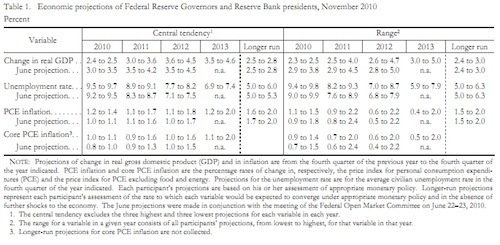

If you're wondering whether Barack Obama will be re-elected in 2012, there's no better place to look at this point than the latest Federal Reserve projections detailed in the newly released minutes (PDF) of their most recent meeting:

What does that mean? Well, it means he should win if the numbers come in on the high end of the range but he has a very realistic chance of losing. How seriously should we take these forecasts? My sense is that we shouldn't take them that seriously—modelers do their best but their best isn't very good. As I kept saying in 2008, election outcomes are hard to predict in advance. But getting a bunch of political reports together in a room to speculate on it doesn't get at the real source of the uncertainty, which is the fact that our economic projections are fairly uncertain.

Meanwhile, in Korea…

As best I can tell the actually important news story of the day concerns the continued provocations of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. I suppose it's actually good that cable news doesn't seem very interested in this story, since coverage would likely be hysterical and counterproductive. Still it matters. And Dan Nexon has some smart things to say about it:

What makes this interesting (and dangerous), is that ROK forces–even without U.S. help–are more than a match for anything that the North Koreans can field. This means that the South Korean leadership has any number of plausible military options; if the South Koreans begin to significantly alter their assessment of current trends, these military options will likely appear increasingly attractive.

Still, none of this suggests an alteration in the basic factors that restrain Seoul:

- Before they collapse, North Korean forces will kill a lot of South Koreans and do a lot of damage to South Korea's economy;

- The United States has no appetite for taking part in an additional large-scale military conflict;

- Uncertainty surrounding Beijing's likely actions in the event of a conflict; and

- The significant challenges that would come from assuming control of North Korean territory if the conflict leads to ROK victory in a full-blown war.

These four factors–two of which aren't particularly manipulable–make significant escalation unlikely. But with the developments of the last two days, I'm less sanguine than I was even after the sinking of the Cheonan–especially about the long-term prospects for a peaceful Korean peninsula.

To me the issue for American policymakers is that it's really not clear why our troops need to be in the middle of this mess. We have no way of mitigating 1 and 3, and no intention I can see of mitigating 4, so at this point our efforts to help South Korea create problems for the United States without offering any clear benefits to our client. Of course we should avoid disengaging in a way that looks like we're somehow selling the ROK out in the face of DPRK aggression, but we ought to be looking to involve ourselves less and less in this.

Corporate Profits Not Actually At Record High

I saw a lot of commentary yesterday about how corporate profits are now at a record high. I think it's worth noting that this is true if and only if you don't adjust for inflation. And I have no idea why you would think adjusting for inflation is a bad idea in this context. A helpful chart the Commerce Department emailed out yesterday illustrates what's actually happening:

The major takeaways from this chart are twofold. One, corporate profits aren't really at a record high. Two, corporate profits hit new highs all the time in an expanding economy. The real story here isn't that nominal profits are at a record high, it's that real profits are still below-peak. Which is just to say that corporate profits, like most everything else, reflect incomplete recovery from the recession. The good news here is that the trends are in the right direction. Profits are rising. Capital expenditures are rising. And the non-financial sector is beginning to back away from stockpiling liquid assets:

This all points to things being better 12 months from now than they are today.

The Height Act and Vacant Land

One recurring theme in this Greater Greater Washington symposium on the DC Height Act is the idea that the presence of vacant lots in non-downtown parts of DC constitutes an argument in favor of the Act's non-malignancy.

I think this is a big mistake. Consider some other inefficient rule about the use of downtown DC space. Maybe the City Council is proposing a rule that everyone in the downtown business district needs to wear blue on Monday, green on Tuesday, red on Wednesday, purple on Thursday, and yellow on Friday. Someone says "you know, that'll be bad for business." But the proponents of the new rule say "no way; not only will the impact be minimal, if anything it'll help the city by encouraging investment in under-developed neighborhoods."

I say false. The best thing under-developed DC neighborhoods have going for them is proximity and connectivity to the valuable land and economic activity in downtown DC. Measures that reduce the value of that downtown land and activity reduce the value of proximity to downtown DC, and impair the chances of development in under-developed neighborhoods. Repeal of the Height Act would, by lowering rents, increase the share of DC-area firms that are located in DC. This would increase the value of connectivity to downtown DC, helping under-developed neighborhoods, and also increase the city's tax base, also helping under-developed neighborhoods. What's more, lower rents would increase the entire metropolitan area's capacity for entrepreneurship and start-ups outside the core politics-and-government industry. This would further increase the value of connectivity to DC-area business centers, further helping under-developed neighborhoods.

If what you think is that the aesthetic value of the Height Act is just so important that it's worth everyone paying higher taxes, higher per capita pollution levels, impaired working class job opportunities, and reduced city services then fine. But I think very few people do think that. So cognitive dissonance produces a lot of creative thinking about why maybe this isn't such a big deal, economically. The reality, however, is that it's a huge deal. Look at the central business district of any American city. Then look at DC. Regulation is massively distorting the allocation of resources in this city.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers