Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2493

November 20, 2010

Booze-Free Hotels

Keith Humphreys stays at an alcohol-free hotel in Morocco and wonders if this might be a workable market niche in non-Muslim countries:

>I wonder if a chain of hotels without alcohol could make it as a niche market in the U.S.

Religiously conservative travelers might like it, just as they do in Marrakech. Families with small kids are another potential source of customers as are I suspect women travelling alone who would like to know that there will not be drunken males in the restaurant or the lobby or anywhere else. People in recovery from alcoholism might also be drawn in. And of course such hotels could also get business from people like me, who wouldn't book a hotel on this basis but at the same time don't care enough about alcohol unavailability to let it stop them from staying at the hotel for other reasons (in my case because it was across the street from where our symposium was held).

I doubt it. Alcoholic beverages are such a high-margin profit for hotels that it creates a huge incentive for them to try to put people in their rooms and restaurant seats on the off-chance that they'll buy a drink. Consequently, non-drinkers are probably getting a great deal from hotels and would have to pay higher prices for something else (food, rooms) since that stuff couldn't act as a loss-leader for the booze. So people would need to put substantially more value on the non-availability of alcohol than I think is plausible.

The Land Market

It's no surprise to me that paranoid tea parties hate the idea of sustainable development, but Stephanie Mencimer's article on the subject does make for amusing reading:

In the tea partiers' dystopian vision, the increased density favored by planners to allow for better mass transit become compulsory "human habitation zones." They warn of Americans being forcibly moved from their suburban dream homes into urban "hobbit homes" and required to give up their cars and instead—gasp!—take the bus to work. The enemies in this fight are hidden behind bland trade-association names like the American Planning Association or ICLEI (Local Governments for Sustainability).

The takeaway I think you should have from this is simply to recall how little of actual politics is driven by contrasting views about the merits of "free markets" and/or "small government." To a first approximation, I would say zero percent of tea party conservatism is driven by attachment to these concepts. You have people here who enjoy their existing low density lifestyles, they like the fact that said lifestyles are explicitly and implicitly subsidized through a variety of public policy measures, and they don't like the idea of losing those subsidies. What's more, they regard their antagonists as somewhat culturally alien. So they're pissed off. The fact that a small government approach to land use would in fact lead to denser lifestyles, more bus commuting, and smaller homes is of absolutely zero interest to them.

November 19, 2010

Endgame

To defeat those evil machines:

— The American people know very little about American politics and public policy.

— In Helmand and Kandahar, 92% of men don't know about 9/11.

— Better airport security.

— Bernanke endorses more fiscal stimulus.

— Further expanding the scope of patents is nuts.

— I'm going to say that cars, rather than ping pong "created the American suburb."

Flaming Lips, "Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots".

The Poor, Internationally

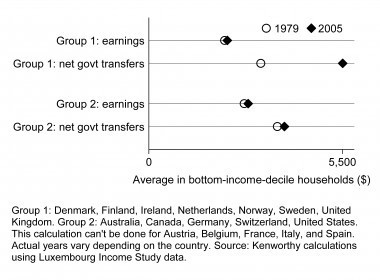

A very interesting Lane Kenworthy post looks at the divergence between developed countries where the poor have shared in economic growth over the past 30 years and those in which they haven't. He finds that before taxes and transfers, things look very similar:

In other words, large scale trends have turned against higher earnings for the bottom ten percent pretty much everywhere. Whatever the source of that—technological, economic, sociological—you see it very widely. What's differed is the policy response. In some countries, as the pie has grown, the state has made sure to give more slices to the neediest. In others, the state hasn't done so. There are a number of ideological implications of this, but I think this adds up to a very hard to assail case for "spreading the wealth around."

Social Security Trust Fund

I really hate this kind of rhetoric from Maya MacGuineas:

"They are nothing like any trust fund that any one of us would think of," says Maya MacGuineas of the New America Foundation. "It conjures up an image of really holding savings, and it doesn't do that at all."

I think this is incredibly misleading. If your rich uncle wanted to set up a trust fund for you and chose to stipulate that the fund should be invested 100 percent in treasuries, that would be a conservative investment choice but it would very much entail really holding savings. The Social Security trust fund is a very real fund that really contains assets—bonds—that represent lending from Social Security to the rest of the government (ROTG).

The only issue with the Social Security Trust Fund is that if you assume ROTG will repay its debts, that means ROTG will need to obtain that many through tax hikes or spending cuts. Conversely, if ROTG avoids tax hikes or spending cuts, that will require additional hikes or cuts from Social Security. But it's hardly as if the overall federal budget deficit is some kind of secret number that people don't know about because trust fund accounting is confusing them. The point is that ROTG is facing a very large budget deficit over the next 30 years, and that insofar as you try to reduce ROTG's deficit by rejecting obligations to Social Security then that merely increases Social Security's actuarial deficit. By the same token, if we reduce federal spending by cutting aid to K-12 schools, then states and municipalities will have a bigger budget gap. The mere fact that the US public sector can be examined at different levels of comprehensiveness doesn't mean that the distinctions are irrelevant somehow.

New START

The idea of voting down the New START treaty seems like either a classic of politics over principle, or else a fundamental failure to understand the idea of agenda setting. Suppose the various conservative whines about the treaty are being offered in earnest. This adds up, at most, to an argument (surely a correct one) that had John McCain won the 2008 presidential election his administration would have negotiated a treaty with somewhat different contours in the details.

But that's not what happened, so we got an Obamaish version of the treaty instead. But what's the treaty? Well, it safely reduces the quantity of Russian nuclear weapons while preserving America's ability to verify what's happening with the remaining weapons. In exchange, the US will dismantle some weapons but still have more than enough to preserve our deterrent. Extra nukes over and beyond what's needed to deter credibly don't do anything for the country—they don't add inches to our national penis or anything—it's just an income stream for certain firms and bureaucrats who deal with the nukes. Basically in exchange for giving up nothing, we're reducing the possibility of something terrible happening with Russia's stockpile. And the people who want to vote the treaty down will kill that. Their stockpile will stay big, and our ability to verify what's happening with it will go away since the old treaty has declined.

Meanwhile, foreigners will wonder wtf has happened with US foreign policy and would-be proliferators will find their efforts somewhat boosted by the collapsing credibility of the disarmament process. And all for what? A cheap political talking point on a fourth-tier issue? A bit of extra pork?

The Billion Dollar Man

Dean Baker really hates Pete Peterson. I don't share Baker's view of Peterson as an insidious figure, I think he's a public spirited man who's spent a lot of money—1 billion dollars it turns out—on a genuine effort to solve a genuine problem. But when you talk about spending a billion dollars on something, the question of priority-setting starts to become pretty urgent. And I agree with Jon Chait about "the establishment's strange debt fetish" except for the fact that I don't actually find it all that strange:

I do think the long-term deficit is a serious issue that I'd like to see addressed. I don't understand the idea that this is an especially good political time to solve it. While many Democrats oppose any revisions to entitlement programs, the entire Republican party is in the grips of anti-tax dogma so powerful that not a single Republican in Congress has defied it for twenty years. Now, a moment of high Republican hubris, seems like a very unlikely moment to force the party to compromise its core policy commitment.

What's truly bizarre is this idea that it's the most urgent issue to address. Climate change seems clearly more urgent–and, what's more, it's probably irreversible. The economic crisis is also more urgent. But Washington elites are fairly removed from the cataclysmic effects of the economic crisis–they're not losing their homes or living in economic terror. And climate change is a "partisan" issue, unworthy of the urgings of a non-partisan wise man. And so, by dint of the peculiar isolation and sociological demands of the members of the political and media establishments, the deficit must become the top priority.

Chait's sociological observations are correct, but there's also the small matter of the billion dollars! It's very difficult to actually change public policy through pure force of monetary expenditures, but it's relatively easy to focus the attention of the media on things simply by paying people to focus on it. Through the Fiscal Times and many other avenues, Peterson has directly subsidized the production of tons journalism and policy analysis on the subject he thinks is interesting. If he were a climate hawk instead of a fiscal hawk, we'd be in a better place. If he spent a bit less money on his fiscal policy endeavors and a bit more on the monetary ideas of Peterson Institute fellow Joe Gagnon the world would be a better place. It's natural that the elite would disproportionately focus on something that a billion dollars is being spent on paying people to focus on. It's just unfortunate.

Parking in New Haven

I never like to visit a place without checking out its local parking regulations. So I found the New Haven zoning ordinance and I looked up the quantity of parking that you need to build in order to construct something in the designated zones for "General High-Density Residential":

One parking space per dwelling unit (except that only one parking space shall be required for each two elderly housing units) located either on the same lot as the principal building or within 300 feet walking distance of an outside entrance to the dwelling unit to which such parking space is assigned, and conforming to section 29 and the remainder of the General Provisions for Residence Districts in Article IV.

To repeat my usual spiel, this will tend to reduce the economic efficiency of the city in which the rule is in force. What's more, it will drive the market price of housing higher than it otherwise would be will driving the market price of parking lower than it otherwise would be. Since cars are expensive and poor people often don't own them, whereas well-to-do families may own several, this amounts to a regressive transfer from the poor to the rich. On top of all that, artificially cheap parking is bad for the environment.

Also note that the density we're talking about here is not in fact very high:

Maximum gross floor area: No such building or buildings shall have a gross floor area greater than 0.5 times the lot area; except that this floor area may be increased by 0.1 times the lot area (up to a maximum of 1.7 times the lot area) for each one percent of lot area by which the building coverage of the principal building or buildings is reduced below the maximum of 25% of lot area set by subparagraph (c) above.

Does it really make sense for the government of an under-populated and economically depressed city to be saying "no thanks" to real estate developers who might want to make a very large investment in the city? There's a place in life for economic distortions, but that place is not when the distortions are also pro-pollution and your city has a poverty rate way above the national average.

Telecommunications Convergence

Shani Hilton writes about how a growing number of people are dropping their cable subscriptions, a trend she thinks will continue:

Many cable providers have been raising prices, and right now, they can afford to do so because most subscribers haven't even considered other options. But as many other industries have discovered, this isn't sustainable in the long-term. The share of live-TV watchers is going to shrink — and if live HD sports become widely available on the internet, it's a wrap — and many distributors will find themselves out of a job. I could be wrong, but I just don't see how they can save themselves.

I think that's both right and wrong. Certainly in a world of much-faster broadband internet there's no particular need to be a cable subscriber. But I get my internet access from my cable company, Comcast. The other major option would be to get it from Verizon, the major local phone company. But of course today you can also get phone service from Comcast and Verizon is increasingly rolling out Fios cable television. And for my part, I don't get landline service from Comcast or Verizon, but I do want a landline so I use Lingo's VOIP service over my Comcast internet connection.

Which is just to say we're seeing not the death of cable, but the convergence of previously distinct telecommunications services. That's a problem for telecom providers not so much because people will drop cable, but because the combined "telecom services" marketplace is a more competitive one than the segmented "cable" and "phone" marketplaces were/are.

Afghans to Be Shocked, Awed By Novel Experience of Heavy Military Equipment, Explosions

It's a bit difficult to know what the most ridiculous thing the US military told Rajiv Chandrasekaran as he was worked on this piece about America's increasing use of tanks in Afghanistan. The ironic invocation of shock and awe sets the table nicely:

"The tanks bring awe, shock and firepower," the officer said. "It's pretty significant."

But for my money, what brings the piece home is this novel rationale for blowing things up:

"Why do you have to blow up so many of our fields and homes?" a farmer from the Arghandab district asked a top NATO general at a recent community meeting.

Although military officials are apologetic in public, they maintain privately that the tactic has a benefit beyond the elimination of insurgent bombs. By making people travel to the district governor's office to submit a claim for damaged property, "in effect, you're connecting the government to the people," the senior officer said.

That's the deepest into the black humor, at least. But what really leaves me scratching my head is what Spencer Ackerman points to here, where General David Petraeus seems to endorse bizarre ideas about his own magical powers:

Chandrasekaran reports that Petraeus feels his reputation as a counterinsurgency guru can overcome the optics of a heavily armored force rolling through Afghanistan's south, reminiscent of the Soviet occupation. But any reporter who spends time in Afghanistan will hear stories from surprised U.S. officers about how many Afghans don't know the Soviets ever actually left. And chances are the Army/Marine Counterinsurgency Field Manual isn't required reading in Kandahar or Marja.

It continually seems to me that the biggest problem with our strategy in Afganistan is that to much too great extent it's really a problem about internal conflicts within the military whose real targets are in Washington DC. The counterinsurgency faction badly wants something called a "win" achieved through something called "counterinsurgency" and I think is losing sight of the real interests of the people in America and Afghanistan alike.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers