Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2490

November 23, 2010

Fanaticism vs Growth

If you want to understand why the American tax code is so inefficient, I'd encourage everyone to read Cato's tax guy Daniel Mitchell who's recently argued that "Tax Loopholes Are Corrupt and Inefficient, but They Should only Be Eliminated if Every Penny of New Revenue Is Used to Lower Tax Rates".

Think about that. If Max Baucus saunters down to the Cato Institute with a plan to eliminate tax loopholes, use 99% of the revenue to lower tax rates, and spend 1% on Pell Grants, Mitchell wants to say "no." He would rather keep massive economic distortions in place than let the federal government get one extra cent of tax revenue. This is a fanatical and insane attitude. In politics, nobody ever gets what they want and never will. But when we're lucky, it's possible to get things that are better than the status quo. But when ideologues of this sort have become so influential on the American right, it's extraordinarily difficult to make any kind of progress on anything.

Educating Children: It's a Good Thing!

The basic idea of the DREAM Act, as I understand it, is this. A certain number of people are in this country illegally. A certain number of those people came to be in that situation because of actions their parents took while they were children. And of that sub-set of people who were transported in America illegally, a certain proportion have avoided committing any crimes, and have graduated high school. The DREAM Act would provide "conditional" legal status to anyone who fits those conditions and agrees to do a two-year term in the United States military, get a two-year community college degree, or do two years of work toward a four-year degree. Upon completion of such undertakings, the person in question could apply for American citizenship.

I'm not really sure why anyone would have a problem with this, but Senator Jeff Sessions of Alabama has all kinds of problems, including with this:

Already, GOP staffers have begun circulating to senators and conservative groups a white paper outlining what they see as the social and financial costs of passing the Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors Act.

"In addition to immediately putting an estimated 2.1 million illegal immigrants (including certain criminal aliens) on a path to citizenship, the DREAM Act would give them access to in-state tuition rates at public universities, federal student loans and federal work-study programs," said the research paper, being distributed by Alabama Sen. Jeff Sessions, the ranking Republican on the Senate Judiciary Committee.

So we're faced with a teenager who was born from Mexico and illegally transported to the United States several years ago. Said teenager has the capabilities needed to do college-level work and/or to serve in the United States military. One option, the DREAM option, would be to facilitate said Mexican-born teenager's efforts to do those things and recruit him to become an American citizen. The other option, the Sessions option, is to hound this kid and make him go back to Mexico. Because why? Because increasing the education level of our citizenry is bad? The various benefits Sessions is whining about here aren't extended as charity, they're extended because education is socially valuable. Today's student loan recipient is tomorrow's productive taxpayer.

At any rate, it's worth emphasizing that Jeff Sessions is America's most racist Senator and definitely in that context his stance isn't surprising.

The Interest Rate Caps of Yore

Glass and Steagall, regulatin'

I liked John Cassidy's article on Wall Street as parasitical I great deal, but I thought one line at the end might end up misleading people:

In 1940, a former Wall Street trader named Fred Schwed, Jr., wrote a charming little book titled "Where Are the Customers' Yachts?," in which he noted that many members of the public believed that Wall Street was inhabited primarily by "crooks and scoundrels, and very clever ones at that; that they sell for millions what they know is worthless; in short, that they are villains." It was an extreme view, but public antagonism toward bankers and other financiers kept them in check for forty years. Economic historians refer to a period of "financial repression," during which regulators and policymakers, reflecting public suspicion of Wall Street, restrained the growth of the banking sector. They placed limits on interest rates, prohibited deposit-taking institutions from issuing securities, and, by preventing financial institutions from merging with one another, kept most of them relatively small. During this period, major financial crises were conspicuously absent, while capital investment, productivity, and wages grew at rates that lifted tens of millions of working Americans into the middle class.

Since the early nineteen-eighties, by contrast, financial blowups have proliferated and living standards have stagnated. Is this coincidence? For a long time, economists and policymakers have accepted the financial industry's appraisal of its own worth, ignoring the market failures and other pathologies that plague it. Even after all that has happened, there is a tendency in Congress and the White House to defer to Wall Street because what happens there, befuddling as it may be to outsiders, is essential to the country's prosperity. Finally, dissidents like Paul Woolley are questioning this narrative. "There was a presumption that financial innovation is socially valuable," Woolley said to me. "The first thing I discovered was that it wasn't backed by any empirical evidence. There's almost none."

It's important to understand the role of the regulation capping interest rates in this scheme. That wasn't a rule about "repressing" evil banksters. It was a rule about setting bankers up with a cozy cartel. The way post-deregulation banking works is that if banks compete to get customers' funds by offering generous interest rates. And since interest on a checking or savings account is basically a commodity product, the price competition tends to lead to the profits all being competed away. Back in the days of the regulatory cap on interest rates, things were different and old-school depository institutions basically had guaranteed profits. The ban on interstate banking had a similar effect—annoying to consumers, but convenient for restricting the level of competition.

The point Gary Gorton makes in his excellent book Slapped by the Invisible Hand is that it's hard to separate out the good and the bad in the process of unwinding this arrangement. The old days of guaranteed profits posed real problems for customers. You can be as skeptical of "financial innovation" as you like and still recognize real value in such innovations as savings accounts with positive real interest rates, branches that are open later than 3PM and sometimes even on Saturday, and other basic efforts to act like real businesses in a competitive marketplace that need to sell products to customers.

But once you bring competition into this field, you largely take the profit out of it. The reason banking used to be dominated by boring "take the deposit, loan the money" business models is that those models were profitable. Deregulated, more competition came into play, consumers got a lot of benefits, but the real money moved elsewhere ("shadow banking") and the industry naturally became dominated less by people who were interested in leaving work early ("bankers' hours") than by people who were interested in dreaming up ways to get rich.

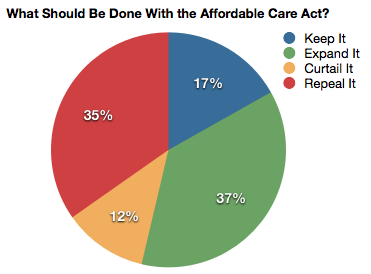

Affordable Care Act Repeal Unlikely, Unpopular

Nobody is head over heels in love with the Affordable Care Act, but McClatchy notes that much of the discontent is from the left and the public constituency for repeal is quite small:

On the side favoring it, 16 percent of registered voters want to let it stand as is.

Another 35 percent want to change it to do more. Among groups with pluralities who want to expand it: women, minorities, people younger than 45, Democrats, liberals, Northeasterners and those making less than $50,000 a year.

Lining up against the law, 11 percent want to amend it to rein it in.

Another 33 percent want to repeal it. Among groups with pluralities favoring repeal: men, whites, those older than 45, those making more than $50,000 annually, conservatives, Republicans and tea party supporters.

Nothing surprising about the demographics here or the outcome. If you polled me on this, I'd count myself as someone who wants to expand the law. To give a more nuanced view, though, I think there's room for both expansion and curtailment. What's more, even though few in Congress want to hear it the reality is that we need to do more health reform. Much more. The cost/quality situation is nowhere near good enough. What's needed, in political terms, is some kind of credible escape hatch through which conservative politicians can engage with changing health care law in some way other than demanding repeal. This is what I think is promising about the Scott Brown / Ron Wyden state waiver initiative.

Oversecured America

I suppose I agree with Kevin Drum about one aspect of the Transportation Security Administration namely that public outrage about the indignities it imposes seems to me to be 80 percent middle class white people not liking the idea of being placed in the subordinate position of a dominance hierarchy, 19 percent about yearning for America to adopt institutionalized racism as the lodestar of our transportation security policy, and maybe one percent about liberty.

That said, I think everything else Drum says is wrong. I think American air travel security was too tight even before 9/11. I think the main lessons of 9/11 should be that keeping weapons off planes is largely futile and that training of flight crews is highly effective. As of the morning of September 11, 2001 the standing doctrine was to allow hijackers to take control of planes and that's what happened. As quickly as later that morning doctrine shifted and the passengers and crew of United Flight 93 brought their own plane down, preventing its use as a projectile.

Not just airlines, but America as a whole is, I think, over-secured against terrorist by this kind of weapon screening. One should back up and consider the baseline. If you assume the existence of a person willing to die for Osama bin Laden's war on America, located within the United States of America, and in possession of a working explosive or firearm, there's basically nothing stopping him from blowing up the 4/5/6 platform at Union Square or the 54 bus in DC or the Mall of America or even the security line at DFW airport. And yet it doesn't happen. Does that mean we could get by with no security anywhere? I say: no. But we should start with the idea that the main point of security is simply to push attacks around. The bank has security guards to encourage you to rob the liquor store down the street. Personal security for a handfull of high-ranking government officials makes sense. Better that some madman take a shot at me than take a shot at the President or try to seriously alter the course of American politics by blowing up a restaurant where John Roberts and Sam Alito are having lunch.

But there are real limits to this. Is the life of the Secretary of Agriculture or the Mayor of Indianapolis really that much more valuable than you or me? We should be skeptical. The public choice argument that the government will over-invest in the security of its own facilities and personnel is strong. Airplanes, in this spirit, seem more vulnerable to attack than buses and deserve tougher security. But don't ask yourself "what amount of hassle and expenditure is worth paying to prevent terrorist attacks," ask yourself "what amount of hassle and expenditure is worth paying to shift terrorist attacks off airplanes and onto buses"? Much of the resources currently spent on "security" measures would be much better spent on having more police officers. Ordinary violent crime continues to be a very serious problem in America, and reducing its incidence would vastly improve people's physical security and free up investigatory resources to make serious plots harder to pull off.

It's the Network

The power of distributors in the mobile phone value chain cannot be ignored. It's not fair, it's not convenient and it's not consumer friendly, but as long as networks are not good enough for mobile computing, mobile computers cannot commoditize the network.

To cite the importance of digital telecommunications to the 21st century economy is cliché. And yet the ongoing massive mismanagement of the wireless spectrum remains a niche issue that's never discussed in mainstream circles.

Paul Ryan's Monetary Economics

Paul Ryan says that "monetary policy was always my first love" but he doesn't seem to know very much about it:

"There is nothing more insidious that a government can do to its people than to debase its currency," Ryan said.

Just as harmful, Ryan warns, is that the proliferation of newly printed dollars inevitably unleashes inflation and throws the economy out of kilter in other ways.

"Inflation is a killer of wealth. It wipes out the middle class. It eviscerates the standard of living for people who have retired or are living on fixed incomes," he said. "Name me a nation in history that has prospered by devaluing its currency." [...]

To Ryan, the root of the problem is the Fed's dual mandate, which calls on the central bank to promote employment as well as throttle inflation. Ryan said he has pushed for years to rewrite the Fed's statutes in favor of a single mandate to control inflation and preserve the dollar as a store of value, making the Fed more like the European Central Bank.

Fighting inflation and boosting employment often are diametrical goals, he said.

"Basically the Fed is driving a car with two feet, one on the brakes and one on the gas pedal, and it's a real jerky ride," he said.

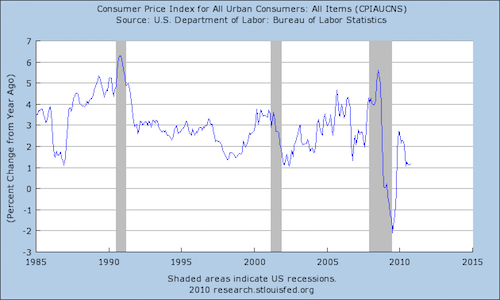

So to sum up, right now inflation is running lower than it was in the 1990s and 2000s. What's more, in the 1990s and 2000s it was running lower than it was in the 1980s. And what the Fed is trying to do is to bring inflation back not to the levels of the Ronald Reagan Era, but to the rate we enjoyed in the 1990s and 2000s. Maybe Ryan's a madman rather than a hypocrite and he did in fact spend the late-80s running around the country terrified of inflation:

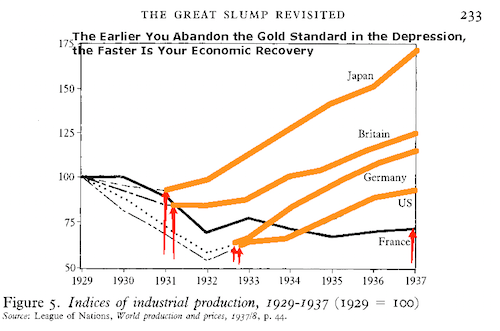

Have countries ever experienced a post-recession return to prosperity in part through currency devaluation? Sure they have. Throughout the Great Depression countries found that only abandonment of the gold standard and currency devaluation allowed for growth to return:

In terms of targeting, Ryan seems to be equivocating between two proposals, one irrelevant and the other insane. One interpretation of what he's saying is that instead of targeting 2 percent inflation and also targeting full employment, the Fed should just focus on delivering 2 percent inflation. I think there's a decent case to be made for that. But it's irrelevant. Inflation is below 2 percent right now and has been below 2 percent for years. If the Fed is targeting inflation alone it should engage in monetary expansion. If the Fed is targeting employment alone it should engage in monetary expansion. And if the Fed is targeting both prices and employment, then it should engage in monetary expansion.

Now Ryan's other idea here is quite different. At various times he seems to think that the whole premises of modern monetary policy are mistaken. A more expensive dollar is always a better dollar, and lower inflation is always better than higher. And if we wanted it to, the Fed could simply refuse to engage in "proliferation of newly printed dollars." The population would grow, the economy would grow, and the quantity of dollars would stay fixed. Consequently, each dollar would increase in value and anyone currently sitting on a stockpile of dollars would benefit enormously. Unlike his target nonsense, this would genuinely be a different policy. But at the same time it would be an economic catastrophe. With the supply of dollars are unable to increase in response to growing demand for dollars, we'd see a shortfall in the demand for everything else. Americans would have the ability to make more stuff and perform more services, but demand for goods and services would be too low to employ everyone. Instead of goods and services, people would want more money. And the Fed would refuse to provide it. So we'd drift along in mass unemployment indefinitely.

November 22, 2010

Endgame

Want you to see everything:

— Bank debt.

— Moscow's crazy parking plan.

— WiFi coming to Virginia Rail Express.

— If we're going to keep adding lines, I think "Circulator" needs a new name and branding.

— Why are conservatives siding with foreign central banks?

— Will Wilkinson .

— New Haven parking map.

I'm loving Kanye West's new album. Here's "All of the Lights".

Melanie Sloan

A lot of eyebrows were raised when Melanie Sloan and her organization, Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, seemed to be shilling for the for-profit college industry. It seemed out of character, since CREW's done a lot of good work. People were less surprised to see that former Bill Clinton lawyer Lanny Davis was lobbying for them formally, since he's been a hired gun for a while now, representing an array of corporate interests.

Now, though, the plot thickens as it seems Sloan has left CREW to go work for Davis. My friend Kay Steiger puts the whole timeline together. It looks an awful lot like just another day in the casual corruption of American politics, though both parties insist it's a coincidence. Either way, they're dead wrong on the issue at hand.

Late 19th Century Population Growth

Ed Glaeser is always worth reading, and his review of a new book about Boston making the point that the city is less exceptional than the author seems to think is excellent:

Puleo marvels at the enormous expansion that Boston experienced after the Civil War, but all of America's largest cities in 1860 experienced extraordinary growth in this period [i.e., 1850 to 1900]. New Orleans, which grew the least, expanded by 129 percent. Boston's population growth rate of 320 percent seems spectacular, except when it is compared with the faster growth rates of New York, St. Louis, Buffalo, Chicago and Brooklyn. Why did all of these urban areas expand so dramatically in the nineteenth century?

One reason for this dramatic urban growth is that America's cities were the nodes of a great transport network that tied together an entire continent. The wealth of the American hinterland was made accessible to the tables of the east coast and Europe because of huge investments in canals and rail. In Boston, as in New York and Chicago, rail lines were laid near to older waterways, and increased the city's dominance over transportation in New England. Manufacturing, freed from large rivers like the Merrimac by improvements in engine technology, could move to cities and take advantage of this growing transportation network.

To go even bigger picture than Glaeser, the thing about this period is just that the country as a whole experienced very rapid population growth. In 1850 there were 23 million Americans (136,881 of them in Boston) and by 1900 there were 76 million, of whom 560,892 lived in Boston. We normally think of this as a period when "the west" was settled by farmers, but there was huge growth in the older cities as well. One key thing is that at that point American public policy wanted to grow. Immigrants were welcome largely without restriction, and the main barriers to denser residential construction were technological. Under the circumstances, people could and did flock to the places where their efforts were most valuable.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers