Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2492

November 21, 2010

"The Perils of Presidential Democracy" Revisited

In his classic essay "The Perils of Presidentialism" (PDF) political scientist Juan Linz noted the striking fact that "the only presidential democracy with a long history of constitutional continuity is the United States . . . [a]side from the United States, only Chile has managed a century and a half of relatively undisturbed constitutional continuity under presidential government—but Chilean democracy broke down in the 1970s." By contrast, many parliamentary democracies have managed to hold together for a long time.

Linz briefly treats the question of why presidential democracy, which basically doesn't work, has managed to work in the United States:

But what is most striking is that in a presidential system, the legislators, especially when they represent cohesive, disciplined parties that offer clear ideological and political alternatives, can also claim democratic legitimacy. This claim is thrown into high relief when a majority of the legislature represents a political option opposed to the one the president represents. Under such circumstances, who has the stronger claim to speak on behalf of the people: the president or the legislative majority that opposes his policies? Since both derive their power from the votes of the people in a free competition among well-defined alternatives, a conflict is always possible and at times may erupt dramatically. Theme is no democratic principle on the basis of which it can be resolved, and the mechanisms the constitution might provide are likely to prove too complicated and aridly legalistic to be of much force in the eyes of the electorate. It is therefore no accident that in some such situations in the past, the armed forces were often tempted to intervene as a mediating power. One might argue that the United

States has successfully rendered such conflicts "normal" and thus defused them. To explain how American political institutions and practices have achieved this result would exceed the scope of this essay, but it is worth noting that the uniquely diffuse character of American political parties—which, ironically, exasperates many American political scientists and leads them to call for responsible, ideologically disciplined parties—has something to do with it.

Linz's article was published in 1990 at a time when the observation about the lack of ideological coherent and rigorous discipline had been true for the overwhelming majority of American history. And, indeed, as recently as 1988 one could have witnessed moderate Democrat Joe Lieberman successfully challenging incumbent liberal Republican Senator Lowell Weicker with the support of, among others, William F Buckley, Jr.

But it turns out that Lieberman vs Weicker was something of a dying gasp of a political order that was rendered obsolete by the civil rights revolution. Twenty years later we find ourselves several congresses into a brave new world in which every single Democratic Party legislator is to the left of every single Republican Party legislator. In terms of partisan politics, in other words, we've become a normal country. But as Linz observed, the "normal" outcome for a country with our political institutions and ideologically sorted parties is constitutional crisis and a collapse into dictatorship.

So far it hasn't happened here. The 1998-99 effort to impeach Bill Clinton was sufficiently unpopular that moderate Republicans wouldn't vote for it. Al Gore chose not to contest the legitimacy of the Supreme Court ruling that handed the White House to George W Bush despite the fact that the electorate preferred Gore. And by 2007-2008, Bush was so unpopular that the Democratic Party leadership felt the wisest course was to avoid provoking a crisis and basically just wait him out. But we live in interesting times….

Green Lantern

Saw the Green Lantern trailer while I was at the movies watching Harry Potter:

It seems a bit weak to me. The normal problem you see with superhero movie series is that a lot of the iconic characters (Superman, Spiderman, Batman, X-Men) have these thematically resonant origin stories that transcend the inherent goofiness of a superhero story. Then when you try to extend the series, the tendency is for things to bog down. But Green Lantern really isn't like that. The origin of Hal Jordan is kind of banal, and the iconic Jordan plotlines I can think of are probably too bogged down in DC cosmos to make any kind of sense to normal people. I think a Kyle Rainer story might be more compelling in this context.

Joe Klein on the Pain Caucus

Why is it that we're so focused on deficit reduction at a time when more urgent problems loom?

here is, for example, Glenn Hubbard, who was featured on the New York Times op-ed page recently in defense of the deficit commission, describing the problem this way: "We have designed entitlements for a welfare state we cannot afford." This is the same Glenn Hubbard who served as George W. Bush's chief economic adviser when Dick Cheney was saying that "Reagan proved deficits don't matter." One imagines that if Hubbard was so concerned about deficits, he might have resigned in protest from an Administration dedicated to creating them. But, no, he's here to speak truth to the powerless — to the middle-class folks whose major asset, their home, was trashed by financial speculators, thereby wrecking their retirement plans and creating the consumer implosion we're now suffering. Hubbard is telling them they now have to take yet another hit, on their old-age pensions and health insurance, for the greater good.

The obsession with long-term deficits is not limited to conservatives. Exuberantly wealthy center-left types who staged a leveraged buyout of the Democratic Party's economic policies in the 1980s — people like the deficit commission's Democratic co-chair, Erskine Bowles — have been reliable foghorns for long-term middle-class sacrifice. They tended to be big supporters of the irresponsible federal lenders Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and most egregiously, they shepherded the deregulation of the financial sector through Congress in the late 1990s. But unlike the Republicans, they trend toward fiscal responsibility. Pete Peterson, a nominal Republican who is a leader of this group, is in favor of higher taxes for the wealthy, means testing for Social Security and Medicare, serious cuts in the defense budget — and even a provision that would tax the profits of private-equity moguls as regular income instead of capital gains, a proposal that his former partner at the Blackstone Group, Stephen Schwarzman, compared to Hitler's invasion of Poland in 1939.

The really noteworthy thing about Hubbard, it seems to me, is this. His administration was involved in deficit-increasing tax cuts. Fine. Maybe conservative care about the deficit, but care about low taxes more. His administration was also involved in deficit-financed wars. Fine. And deficit-financed increases in domestic security spending. Fine. And in deficit-financed increases in the "baseline" defense budget. Fine. Maybe conservatives care about the deficit, but care about hawkish security policies more. Fine. But his administration was also involved in a deficit-financed increase in Medicare benefits! So the concern is . . . what . . . ? But somehow now mired in a severe recession with huge quantities of idle resources and idle workers now we're supposed to worry about the deficit.

Institutions Matter

Reihan Salam lauds the tactical approach of New Jersey Governor Chris Christie:

That is, Christie's position can be both uncompromising and bipartisan. Consider the campaign by Democratic mayors in New Jersey cities and towns on behalf of Christie's "toolkit" for local governments. On Monday, The Jersey Journal offered the following report:

Today, Senator Brian P. Stack urged statewide support of Gov. Christie's "toolkit."

Christie has recommended reform in the areas of civil service, collective bargaining, employee pensions and benefits, red tape and unfunded mandates, election reform and shared services.

Sen. Stack said, "I urge both my colleagues in the Legislature as well as fellow mayors to show their support for the Governor's toolkit, which is designed to allow New Jersey's municipalities to operate with better fiscal efficiency."

Gov. Christie has certainly been sharply critical of some constituencies, but he's made an effort to build alliance with Democratic officials and with members of private sector unions who are concerned about the sustainability of demands being made by public sector unions.

Where some see tactical innovation here, I see institutional innovation. If you pay attention to what Senator Stack is saying here, you'll note that he's a State Senator and a mayor. Qua State Senator he's a Democrat and probably much more sympathetic than Christie to the demands of public employees. But qua mayor he needs to make his budget add up, and thus is more sympathetic than the average Democrat to the idea of a "toolkit" that helps expand mayors' budgetary options.

Imagine how different United States Senate debates over federal fiscal aid to state and local government would look if several Republican Senators were also state governors. Instead of Governor Christie turning down federal funding for a commuter rail tunnel because he was worried about potential overruns' impact on the state budget, Senator/Governor Christie might have struck a deal for the feds to finance the project more generously. And of course there's no filibustering in the New Jersey State Senate. State government is also just different from federal government. Every Democratic governor who's presided over a recession ever has ended up cutting state spending, whereas every Republican President since Herbert Hoover has ended up increasing federal spending.

The point is simply that institutions matter. A lot. Always. Politicians matter too, but human beings are prone to be too interested in the personalities that inhabit structures of power and insufficiently attentive to the nature of the structures themselves.

Hippie in the House

Ezra Klein did a post on Friday puzzling over why there's so much more hubub about Nancy Pelosi keeping her job than over Harry Reid keeping his:

Pelosi might be a bit more unpopular, but they're both pretty unpopular. And Pelosi is a lot less vulnerable in her district than Reid is in his state.

Another possible answer is that Democrats lost their majority in the House, but not in the Senate. But it's hard to give that explanation much credit, either: Senate Democrats would have lost the majority if all of them had been up for reelection. They hold the chamber because only a third of the Senate was up for election, not because Reid's forces were more popular than Pelosi's.

I don't actually find this very puzzling. If you look at the record, when Pelosi first became Minority Leader people suggested that Democrats were doomed. When the Democrats won the House in 2006, there was an immediate cry to . . . replace Nancy Pelosi with Rahm Emannuel. Then after 2010 again come the calls to dump Pelosi. Basically no matter what the question the answer is "dump Nancy Pelosi." And that's because, basically, she's a DFH. Of really powerful politicians in America, she's the most left-wing. And of real liberals in American politics, she's the most powerful. Reid's not like a stealth conservative or the second coming of Ben Nelson or anything, but when the body politic swings to the right he swings with it. He voted to authorize the use of force in Iraq and voted no on the Levin and Durbin amendments to temper it. Pelosi led the opposition in the House, breaking with the caucus's then-leader Richard Gephardt.

You may recall that when consideration was given to the idea of making John Kerry Secretary of State, one objection raised was that "Russ Feingold (D-Wis.) stands behind Kerry in line for the gavel, but Senate insiders have speculated that Feingold may be too liberal for the chairmanship." One of the informal rules of Washington is that real liberals aren't supposed to get real power. Pelosi is an affront to that rule. So she's had a target on her back from the get-go.

November 20, 2010

Living in America

The President of the United States can unilaterally order the assassination of an American citizen, but needs the cooperation of opposition party Senators to get an Assistant Secretary of Commerce or a US Marshall in office.

Incremental Inflation

If you want a good plain English explanation of what the new Gauti Eggertsson and Paul Krugman paper on "Debt, Deleveraging, and the Liquidity Trap: A Fisher-Minsky-Koo Approach" (PDF) says, you should of course turn to Paul Krugman here or here.

But I did want to call attention to one side-issue. Back on November first, Krugman blogged:

It's also crucial to understand that a half-hearted version of this policy won't work. If you say, well, 5 percent sounds like a lot, maybe let's just shoot for 2.5, you wouldn't reduce real rates enough to get to full employment even if people believed you — and because you wouldn't hit full employment, you wouldn't manage to deliver the inflation, so people won't believe you.

I said that didn't make sense to me and that a modest increase in inflation expectations should deliver a modest result, not no result. And in the new Krugman/Eggertsson model this comes out my way:

Where this model adds something to previous analysis on monetary policy is what it has to say about an incomplete expansion – that is, one that reduces the real interest rate, but not enough to restore full employment. The lesson of this model is that even such an incomplete response will do more good than a model without debt suggests, because even a limited expansion leads to a higher price level than would happen otherwise, and therefore to a lower real debt burden.

Victory. The real story of the model is that an increase in government purchases would have the most effect. And I'm all for 'em. But it's also worth thinking about what kinds of endeavors it's feasible to undertake at very large scale. Transfer payments—i.e., the government mails checks to people—aren't as well-targeted, but the logistics of adding a zero to the check are very easy. And such transfers could be "money-financed"—i.e., paid for by increasing the money supply rather than by increasing government borrowing—and thereby work on both sides of the issue. This is the fabled helicopter drop of yore and with Helicopter Ben himself running the Fed I'm continually surprised we're not seeing more discussion in the policy community of what it would take to get the choppers off the ground.

Skilled Immigrants

I was at a dinner Thursday night where an ideologically diverse group of people were talking about entrepreneurship, and basically everyone agreed that America could boost its growth rate by being more welcoming to skilled immigrants. And frankly, I just don't see any way of disputing this. I think low-skill immigration is good for America, but even by the standards of those who think it's badly surely more high-skill immigration would be a good thing. If we automatically let foreigners who complete a degree at an American university stay as a permanent resident, they're not going to end up on food stamps or selling drugs on the streetcorner or whatever it is people are worried about.

There are a lot of different mechanisms through which the goal of more high-skill migrants could be achieved, and we should be doing them.

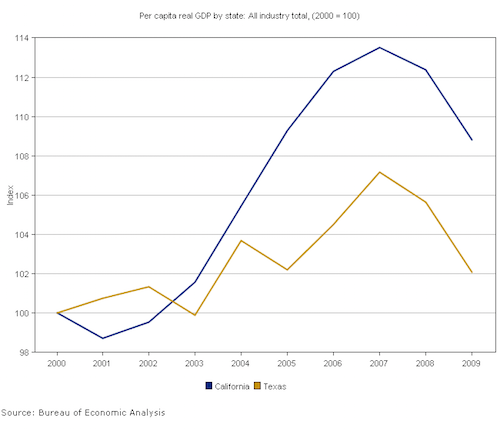

The Texas Miracle

Noteworthy chart, from Ryan Avent:

I do expect that in the future Texas' relatively growth-friendly approach to new construction will continue to make it a major destination for migration. California would be well-served by increasing the level of density allowed in its most vibrant cities. But much myth-making aside, there's no Texas growth miracle.

Priorities

It's hard to believe the FBI is wasting time going after financial sector corruption when there are still all these pot smokers running free in the United States. I hear a funny-looking guy named Barack Obama's even done "a little blow" in his time.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers