Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2495

November 18, 2010

Defense and Engineering Talent

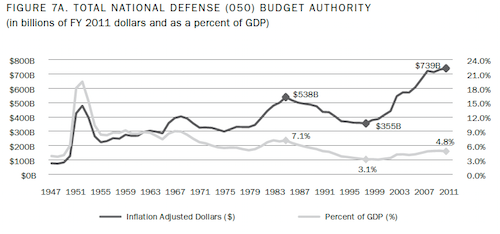

Defense contractors quoted in Mark Thompson's piece on the Pentagon budget raise an important and too-often-neglected issue:

The defense industry recoiled from the very notion. "The highest constitutional responsibility of the federal government is to protect the American people from foreign aggression," said Marion Blakey, head of the Aerospace Industries Association, a major defense trade group. "The co-chair recommendations in the defense arena, if implemented, would exacerbate the coming shortage of engineers and undercut the capability of the nation's defense industrial base to design, build and support complex cutting-edge defense systems."

I'm glad to see Blakey put this on the table, though her perspective on which way it cuts is bizarre. The point is that you have to think not just about the fiscal cost of things, but also their social costs. If we give US Marshalls slightly shinier badges, that might cost some money, but there are no negative broader implications. The real problem with overspending on defense, by contrast, is that the defense establishment competes for people with civilian sectors of the economy. The guys who are building these cool military exoskeletons, for example, are obviously very talented. And the supply of talented engineers isn't all that elastic. When they supply their talents to defense-related projects, the civilian economy is starved of talent.

Sometimes this makes sense. The Manhattan Project involved a huge proportion of the world's finest scientific minds and rightly so. But undertaking that kind of civilian to military brain drain all the time can be very harmful.

Engineers aside, it seems to me that there's a broader worry here about military personnel. It seems to me that there's substantial (though obviously imperfect) overlap between the kind of character traits and skills that make for an effective soldier and make for an effective police officer. Here, too, merely looking at the fiscal cost of paying a soldier's salary doesn't capture the real effects. Some countries don't really try to maintain first-rate personnel quality in which case soldiering serves as a kind of useful employment and job training scheme. But America is trying—and succeeding—to field a huge quantity of very good soldiers which takes the people with the potential to be highly effective soldiers out of the civilian economy where they could be doing other things.

The Domenici-Rivlin Plan

I agree with Jon Chait, the Domenici-Rivlin debt reduction proposal is a lot better than the Simpson-Bowles one. That reflects, I think, the chairs' greater level of actual involvement with budgetary issues. The highlights:

— Higher Social Security benefits for the poor, lower benefits for the rich.

— Slightly lower cost-of-living adjustments for everyone.

— Increase in payroll tax cap.

— 6.5 percent Value Added Tax.

— Income tax reform similar in spirit to, but less regressive than, Simpson-Bowles.

— One-year of fiscal stimulus via FICA holiday.

— Followed by four years of domestic discretionary freeze.

— And five years of defense spending freeze.

As I've said on a number of occasions now, I think there's no reason whatsoever to try to raise money through a VAT rather than a carbon tax. And I can't think of any reason why Pete Domenici would think a VAT is better than a carbon tax. Even if climate change is a total fraud, a carbon tax is still a superior idea. But it would violate the terms of contemporary conservative political discourse to acknowledge any of this. Meanwhile the most important distinction between this and Simpson-Bowles is that the proposed Medicare changes aren't just hand-waving. That makes it, I think, a viable document for people to debate and bargain over. If the centerpiece of your plan is "reduce Medicare spending by magic," then there's really nothing to talk about. But this puts concrete ideas on the table that people can accept or, if they don't accept them, they can propose alternatives:

— Ten-year phaseout of employer health insurance tax exclusion from 2018-2028.

— Raise Medicare Part B premiums from 25 to 35 percent of total program over five years.

— Force pharmaceutical companies to accept lower Medicare payment rates.

— Higher copays.

— "Bundled payments" for post-acute care.

— Transition Medicare to a finite subsidy for health care rather than an unlimited commitment.

This is fairly ugly stuff, but it also represents fairly real ideas. People who don't like the soft price controls idea can instead propose sharper premium hikes. People who don't like the higher copays, can come up with an extra area of medical purchasing to apply price controls to.

Ross Douthat decided to interpret liberal discomfort with the slipshod nature of the Simpson-Bowles proposal as telling you "something important, and depressing, about liberal intransigence". Obviously some people will take an intransigent line on Rivlin-Domenici as well, but not me. This is a proposal one can worth with, though I still think it's perverse to have everyone talking about it with unemployment over 9 percent.

Breaking the CBO

By tradition, the House and Senate budget committee chairs alternate between who gets to pick the Director of the Congressional Budget Office. So it was John Spratt who picked Doug Elmendorf, and as his term expires it should be Kent Conrad's job to pick the next guy, and Conrad wants to keep Elmendorf in place. But in formal terms, the choice requires the concurrence of the leaders in both the House and the Senate, so John Boehner has the authority to break with tradition and block Elmendorf's reappointment.

John Maggs reports that Boehner is inclined to do just that because he's "still angry about Elmendorf's role in health care."

This seems to me like an example of a guy who doesn't know how good he's got it. When the job came open, there was no check on the Democrats' ability to appoint whoever they wanted. They could have put in a strong partisan or a big-time liberal, someone who would produce CBO scores showing that clean energy legislation would boost growth or health care would generate ponies for everyone. Instead because neither Spratt nor Conrad is very liberal, they hit upon a not-very-liberal CBO Director choice. Consequently, under the leadership of the not-very-liberal Doug Elmendorf the CBO has consistently angered environmentalists by overstating the costs of action and understating the costs of inaction. The CBO also spent the entire health reform debate angering reformers by assuming no efficiency improvements due to better incentives.

Consequently, Elmendorf's "role" in the health reform debate was to make a fair amount of trouble for Democrats. And in turn, for a brief shining moment Elmendorf and the Congressional Budget Office became the American right's best friends. Op-eds, floor speeches, TV hits, radio spots, etc. were full of high praise for the CBO. Sing, sing, sing the praises of Elmendorf and his budget scorekeepers. Elmendorf had "proved" that the Orszag/Cutler ideas about bending the curve were false. He's laid-bare the fallacy of the whole effort. Senator Chuck Grassley even analogized the CBO to God.

What happened then was CBO analysis in hand, congressional leaders worked to change the bill to bring it in line with the CBO's ideas of what measures would reduce the growth rate in costs and produce deficit reductions. Suddenly conservatives stopped believing in the CBO. And now Boehner appears to have cooked up an alternate version of history in which "the White House leaned on Elmendorf and that Elmendorf caved" when what in fact happened was that Elmendorf gave the bill so-so marks and the congressional leaders caved and changed the bill.

At any rate, the "rotating" system is a good idea because under the rotating system there's always someone in a position to make a choice. If we shift to the Boehner system where the House and Senate leaders need to agree, then in the contemporary environment of polarized parties, the CBO leadership will be caught in a tug-o-war whenever there's a partisan mismatch. This will sharply reduce the prestige of the CBO and likely result, at the margin, in a lower technical quality of legislation further driving the US Congress toward being a national joke.

Peace in Our Time

I was up at Yale talking international law and global governance. When folks like me start waxing eloquent about world peace and cooperation, it's easy to dismiss us as utopian. Look how far we are from that end-state! It's unimaginable. And I point them to this point about France and Germany:

Yes. Let us give thanks that the most brutal and blood-soaked border in the world is quiet–a border inhabited on both sides by those bloodthirsty peoples who have been numbers one and two in terms of the most effective killers of foreigners for centuries.

Who am I talking about? The Germans and the French, of course

It is now 65 years and 9 months since an army crossed the Rhine River bearing fire and sword. This is the longest period of peace on the Rhine since the second century B.C.E., before the Cimbri and the Teutones appeared to challenge the armies of the consul Gaius Marius in the Rhone Valley.

The story behind why worrying about a "big blowup in Europe" now is a worry about bank defaults rather than the wholesale destruction of major cities is a long and complicated one. But what's clear is that it couldn't have happened without the rise of liberal sentiments on the continent and the construction of liberal institutions to go along with them. France is still France, Germany is still Germany, and the continent still has various problems. But the problem of war has been abolished, just as it has on the US-Canadian border, between the United States and Japan, and in other portions of the globe. The trend worldwide has been toward fewer cross-border wars and fewer and less deadly internal conflicts as well. Working toward further reductions—toward peace—is by no means futile.

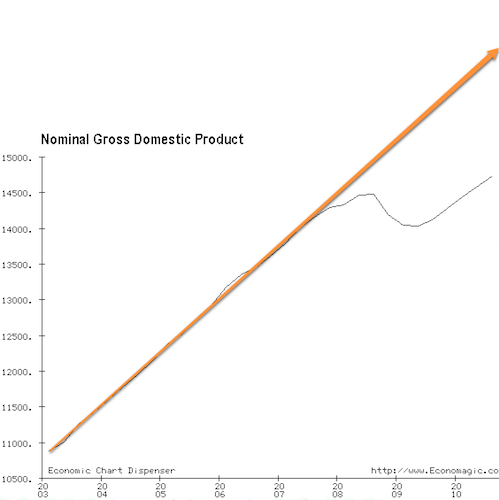

Growth: The Ultimate Deficit Reducer

As David Leonhardt observes, ultimately the state of the public fisc depends an enormous amount on the rate of economic growth. The growth rate, in turn, depends to an extent on the existence of credible fiscal plans. But it's important to keep an eye on growth.

It seems to me that it's actually not a mystery how America could increase our rate of economic growth. In the short term, print money and start mailing it to people; say you're going to keep doing it until we close the gap in nominal expenditures. That the policy elite seems to have persuaded itself that there's some big mystery about how to achieve this baffles me—the guy in charge explained it quite clearly years ago:

Then there's a bunch of perfectly textbook stuff. Create more legal routes for people to immigrate to the United States. Stop taxing imports of clothing. Let Americans buy as much foreign-grown sugar as we want to. Stop taxing imports of food. Close tax loopholes and lower tax rates. Let people build denser and with less parking if they want to. Use pricing to reduce the chronic congestion plaguing our most dynamic metropolitan areas. If we need more tax revenue, levy taxes on pollution not on work. Don't keep so many people in jail and don't make it so hard for them to get jobs when they get out. If Americans have some stuff they want to sell to Cubans, and Cubans have money to buy it, let us sell it to them.

There's more to life than these items, and I also have some more exotic policy ideas. But this is all stuff that will boost growth. And it's all stuff for which the argument why it will boost growth is uncontroversial. We have non-economic reasons for creating all these distortions, but in none of these cases are the reasons in any way compelling. Knocking it all off wouldn't eliminate the need to continue the work of transforming the health care sector, but it would make things quite a bit easier in a whole bunch of ways.

November 17, 2010

Endgame

They don't love you like I love you:

— Constitutional monarchy is good for women's equality.

— "A number of States register or license interior designers"; are there big problems in the states that don't?

— Ron Wyden, dreaming of tax reform.

— Sarah Palin has the reading list of a presidential candidate.

— White House decides to suck up more to the US Chamber of Commerce.

— Women make up just 24 percent of the people "interviewed, heard, seen, or read about in mainstream broadcast and print news."

Undergrad yesterday told me he likes the blog but dislikes the "hipster music" I allegedly favor. The Yeah Yeah Yeahs' totally awesome "Maps".

American Politics Was About Race Long Before Barack Obama Came on the Scene

Adam Serwer commented on racial attitudes and the Obama agenda earlier today, :

I think it's wrong to suggest that opposition to Obama's agenda is "race-based," because that suggests conservatives would feel differently if Obama weren't president. I think the GOP's general positions on the issues would be the same if Hillary Clinton were president.

I think that's basically true, but in some ways it misses the point. American political behavior is heavily shaped by racial attitudes in ways that are much more fundamental than the race of the candidate. Just look at the extraordinary racial gap in voting behavior that occurs clearly and consistently every time a white Democrat faces off against a white Republican. Or look at how nominating Michael Steel didn't make African-American Marylanders suddenly love Republicans. Stephanie Mencimer found a good example of this in the American Values Survey when she observed a big partisan gap in the answer to the question of whether or not discrimination against whites "is as big a problem as discrimination against blacks and other minorities."

56 of Republicans (and 61 percent of self-described tea partiers) say it is, but only 28 percent of Democrats agree. Among white voters, more ethnocentric attitudes are associated with less support for means-tested welfare and more support for universal social insurance. It's difficult to get this stuff acknowledged in the media because people get very defensive about accusations of racism. But the genius of the Mencimer question is that it's really just a question. Evidently a question Americans disagree about. And in a way that's systematically related to broader political issues.

I think it's fair to say that putting an African-American presidential candidate on the ballot increases the salience of some of these divides over racial topics (I don't think I would have seen so many of my black neighbors standing on long lines to buy special editions of the post-election copy of the Washington Post had Hillary Clinton been the Democratic nominee) but racial issues have been important drivers of American politics since before the Constitution was written.

The Importance of Models

David Brooks' latest column has already been subjected to a lot of solid criticism, but I did want to highlight one thing he says which I think inadvertently illustrates why formal models are important and intuitive thinking about virtue won't cut the mustard:

It all makes one doubt the wizardry of the economic surgeons and appreciate the old wisdom of common sense: simple regulations, low debt, high savings, hard work, few distortions. You don't have to be a genius to come up with an economic policy like that.

Try to draw up a model—a simple one, but one where you do try to make sure that your numbers all add up—in which everyone has high savings rather than high debt. Households have high savings. Firms have high savings. The government has high savings. And the governments of your trading partners have high savings. But so do their citizens. And their firms, too. It's the old wisdom of common sense! You'll find that it doesn't add up. Japanese people save by lending money to the Japanese government, which borrows. I borrow to buy a condo, and the money I'm borrowing is the money other people have saved in the bank. You put your money in the bank rather than leaving it under the mattress because the bank pays you interest. But they pay you interest because they can charge interest to other people—people who are in debt.

The old wisdom isn't nutty or anything. Borrowing a ton of money so you can buy a fancy new car is probably a worse idea than buying a cheap used car and saving your money. But if you're poor live in a city with bad mass transit and you borrow money to buy a cheap used car so you can make sure you're on time for work every day, you're making a prudent investment in your own future. Likewise, if you've got a successful store and you take out a loan to open a second location, you're building the future of the American economy. Thriftiness is a good character trait because it tends to make people averse to accumulating debts for frivolous reasons. But if you try to build a systemic model, you'll see that universal thrift doesn't work at all.

Indeed, though thrifty people play an important role in making the economy function, they do so in part because their thrift creates resources that others can use to be venturesome and fuel innovation, entrepreneurship, and prosperity. Capitalist success stories are built on the ability and willingness of people to fail. For every hugely successful startup, you've got a dozen or more failures and behind those failures you've got bad loans. The willingness to issue those loans makes the world go 'round, and we need the savers because without them there's no money to lend.

Apizza

Had a very nice time up in New Haven, but I was a little bit shocked to meet a Yale senior who's never managed to walk the fifteen minutes off campus it would take to walk to Wooster Square to sample the real local pizza at Sally's or Pepe's. Obviously I'm not going to recommend that anyone actually attend Yale, but if you do choose to make that particular mistake with your life it's definitely in your interest to have some New Haven-style "apizza" for your trouble. I'm a New Yorker and fundamentally my loyalties belong to John's on Bleeker Street, but the New Haven stuff is interesting and the places near campus don't really serve it.

Meanwhile, one beneficial consequence of America's 8 years of misrule by a Yale alumnus is that a certain amount of apizza is now available in DC. Pete's in Columbia Heights is the main spot for it but Comet Ping Pong's rendition of the clam pie (called the "Yalie") is also good.

Which is the best apizza joint in New Haven is an issue I hope Michael Symon will address on a "Food Feuds" episode one of these days. I haven't visited enough to have a real opinion on this.

Open for (Private Equity) Business

Andrew Ross Sorkin, in the course of responding to Malcolm Gladwell, says "the private equity industry and its many lobbyists have been fighting for years to prove their value to the public, producing all sorts of studies and white papers to back up their claims."

Is this really true? Can I get my hands on some of this money to back up the claims of the private equity industry? It seems to me that they're clearly correct. Widely dispersed ownership of publicly traded firms presents massive problems of governance and huge misallocations of resources. It's a necessary evil because it allows for the mobilization of capital that would otherwise be sitting around uselessly. But clearly insofar as private equity dudes are able to mobilize capital in other ways, that's fine. If there's a problem of some people getting too stinking rich as a consequence, then those people should pay more taxes. But there's nothing wrong with there being an industry in that field as such.

I'd say more, but I hereby resolve to not write another word on the subject until someone cuts me a fat check to do so. I'm not too proud to beg.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers