Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2243

July 14, 2011

Intellectual Property In The Anti-Trek Economy

In Star Trek and especially Star Trek: The Next Generation, we have our culture's most fully realized vision of a socialist utopia. The combination of replicator technology with abundant clean energy mean that labor has become not only a means of life but life's prime want, so the narrow horzon of bourgeois right can be crossed in its entirety. Society inscribes on its banners: From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs (see here and here).

But Peter Frase asks what does this technology look like without the socialist utopia. The answer is it's all about the intellectual property:

In order to get access to a replicator, you have to buy one from a company that licenses you the right to use a replicator. (Someone can't give you a replicator or make one with their replicator, because that would violate their license). What's more, every time you make something with the replicator, you also need to pay a licensing fee to whoever owns the rights to that particular thing. So if the Captain Jean-Luc Picard of anti-Star Trek wanted "tea, Earl Grey, hot", he would have to pay the company that has copyrighted the replicator patter for hot Earl Grey tea. (Presumably some other company owns the rights to cold tea.)

This creates a stream of rents to copyright holders, as well as employment writing replicator patterns, plenty of jobs for lawyers engaged in endless IP law disputes, etc. And, thus, the market economy is saved!

Breakfast Links: July 14, 2011

— Army experimenting with smartphones.

— Austerity's the wrong prescription for Italy.

— African ethnic groups do about equally well economically on both sides of international borders.

— Mediterranean diet on the decline in Mediterranean countries.

— Spencer Bachus thinks FDR and LBJ caused current economic woes, presumably interspersed with decades of prosperity.

— Jonathan Bernstein on Eric Cantor.

— In Cantor's defense, he keeps saving liberal from President Obama's desire to make a very right-leaning Grand Bargain.

— Lindsey Graham says Republicans have no one to blame but themselves.

— If Microsoft is right and tablets are PCs, then Windows marketshare is falling fast.

July 13, 2011

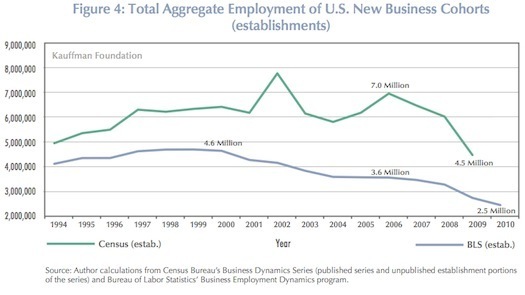

Why Do Census And BLS Figures On New Firms Differ So Much?

The Kauffmann Foundation has been pushing its paper on how new firms are generating and retaining substantially fewer jobs than they used to, and this trend predates the recession out into the blogosphere this week. But I don't really know what to say about it. This point on the data they used to reach the conclusion is, however, quite interesting:

Because of unknown differences in the data sources from Census and BLS—a mystery we urge other researchers to tackle—employment within business cohorts is somewhat cloudy. The Census Bureau's data on employment appear significantly more positive than the BLS data. But, rather than attempt to sort out the differences between the two series here, we simply present both, and urge readers to recognize that, despite the differences, the overall story in both series is disturbing.

People don't spend much time worrying about government data, but it actually matters quite a bit what we do and don't have information on and how reliable the information is. I often wish, for example, that the government tried to track the price of urban land.

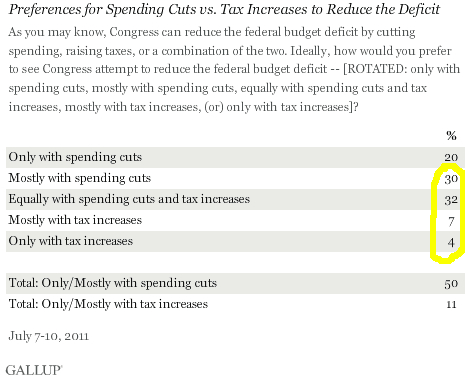

Public Wants Deficit Reduced Mostly, But Not Exclusively, With Spending Cuts

One reason for President Obama to be so aggressive in offering to do deficit reduction primarily on the spending side is that his position commands overwhelming support this way:

To clarify something, I've seen a few non-insane people who think they agree with the Republican position because the looming expiration of the Bush tax cuts means increased taxes are already baked into the cake. That's a mistake. What's under discussion is raising taxes relative to current policy rather than relative to the current law assumption that that the tax cuts will expire.

Good Governance Is Key Ingredient To Sustainable Agriculture

By Matthew Cameron

As U.S. politicians continued to fret over the national debt, a small group of scientists, policy experts, and journalists gathered at the National Press Club this morning to discuss a truly frightening long-term problem: how to feed a world population that is projected to exceed 9 billion people by 2045. The title of the seminar was "A Greener Revolution: Improving Productivity and Increasing Food Security by Enhancing Ecosystem Services," and the key take-away was that more effective governance rather than new technology or advanced farming techniques is going to be the chief determinant of whether the world can avoid a catastrophic population crash before the conclusion of the 21st century.

There are a couple unique characteristics of food production that make it particularly dependent upon government regulation. First and foremost, it is an industry that is necessary for human survival. Whereas people can choose whether or not to buy other products based on their economic conditions and preferences, it is biologically essential for individuals to obtain a certain level of daily nutrition from food. Additionally, two of the primary inputs of food production — fertile land and water — are finite public goods that many different people share. Thus, without effective government regulation, there will be severe pressure placed upon these resources as individuals appropriate them without regard for the aggregate impact had by their entire community.

Policymakers must face a difficult reality: The U.S. model of deregulated, high-intensity crop production is not exportable around the world. In fact, it isn't even viable domestically in the long run. This is because the capital-intensive mode of production that has worked so well in other industries simply cannot escape the inflexible resource constraints of the natural world. Sure, it's possible to use machines to clear large swaths of forest in order to plant more corn or soy, but eventually farmers will either run out of water with which to irrigate those crops, deplete the soil nutrients to an irreversible point, or just add so much carbon to the atmosphere (by eliminating the sequestration potential of the trees) that climate patterns will change and render the local environment inhospitable to any form of agriculture whatsoever.

Instead of allowing for this to happen, it makes more sense for governments to recognize the constraints up front and implement policies that responsibly manage production. Unlike with crops, the U.S. has embraced this approach with some success in the management of its fisheries. Superior technology also has helped, but there's no getting around the fact that without government limits on bycatch, it would simply be cheaper and more efficient for fishermen to use nets to catch tuna while sweeping up dolphins and sea turtles in the process.

The challenge in applying these lessons to the developing world, however, is ensuring that regulatory regimes are effective. After all, even the U.S. has struggled to make its organic certification process seem legitimate due to intense industry opposition to higher standards. Thus, it makes sense for international aid to focus on not only providing food to drought victims and seeds to farmers, but also on providing guidance to bureaucrats and policymakers attempting to create the proper standards and incentives for sustainable agriculture in their own nations.

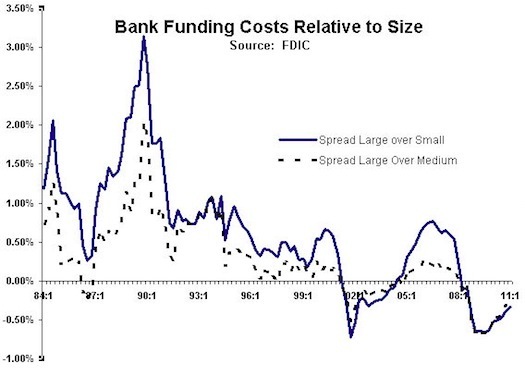

Chart Reading With Mark Calabria

Cato's financial regulation guy, Mark Calabria, has an interesting post up suggesting we use the market test to see whether or not the Dodd-Frank bill has credibly persuaded bondholders that they won't be bailed out on the grounds of "too big to fail."

So what do the debt markets say (if they could speak)? The accompanying chart shows the difference between funding costs for the largest banks ($10 billion plus) and the smallest ($100 million and less), the dotted line shows the same relationship for the largest over mid-sized banks, to help determine how much of this advantage might be driven by economies of scale.

This looks to me like a chart showing that the cost advantage of large banks has diminished since Dodd-Frank was signed into law and that it might diminish further if congressional Republicans and libertarian think tankers stopped promising to defund, repeal, or otherwise sabotage it. Instead, Calabria concludes that "[d]espite whatever Dodd-Frank intended, the debt markets are speaking pretty loudly: too-big-to-fail is still with us." That seems like an idiosyncratic reading to me. But it even gets worse. The thesis that looking at the debt market was a good idea sounded compelling to me, but if you look at the chart it shows clearly that during the peak bubble years large banks didn't have a funding advantage. The large bank funding advantage was a consequence of the crisis, not a cause of it. So why are we even looking at this?

If People Had More Money, They Would Spend It On Things

The Atlantic jobs "debate" continues as Ryan Avent notes that America would produce more real goods and services if people were spending more money, and people would spend more money if there was more money around to spend:

How can it do that? Quite easily, actually. To increase spending, the Fed needs only to increase the money in circulation. It can do this by creating dollars and using them to buy things: Treasury bonds, as it did on a modest scale with its quantitative easing (QE) programs, or other securities. As money in circulation rises, so too will the value of spending.

You could also accomplish this by reducing the interest paid on excess bank reserves. This rate, unlike the short-term treasury rate, can go below zero. This is a policy that has worked well in Sweden. Banks penalized for holding excess reserves will presumably lend to someone. Make the penalty large enough, and banks may even lend money at negative rates. Alternatively, they'll just go out and get fancier office furniture. Either way, money gets spent.

Nobody Can Repossess The United States

RS writes via email:

Last night on The Daily Show, Jon Stewart was joking about the debt limit debate and cracked that we're so worried about the federal government being unable to pay its bills that we have to park it around the corner so that the Chinese don't repossess it. Joking aside, this highlights a misconception among the public: that federal debt, particularly foreign ownership of foreign debt, is bad because foreign countries can use it as leverage to take over the U.S. I think this confusion arises because most people fail to realize the fundamental difference between personal debt and government debt. Most individuals who have debt have secured debt, that is that the loan they got to buy their car or house is backed up by the car or house itself. If the individual doesn't pay, the asset gets repossessed. Government debt, on the other hand, is secured only by the promise that the government will pay when it promises to. People who buy debt in the form of U.S. Treasuries are not buying an ownership interest in the U.S. All they get is a promise. So the Chinese can never cash in their holdings in Treasures by repossessing parts of the U.S. But there seems to be paranoia, particularly on the right and from organizations like the Peter G. Peterson foundation, that the U.S. government's debt opens us up to weakness because of the idea that debt holders are buying up U.S. debt in order to take over the country. This misconception is based on a fundamental confusion between personal secured debt and government bonds.

Yessir. Of course if Vietnam owes China a lot of money and tries to default, China could try to invade and get paid. But that's just another way of saying that large states can use military coercion against small ones. A country doesn't need to be indebted to find itself invaded by a superpower. Just ask Saddam Hussein.

It's important to understand that Chinese purchases of American debt aren't an equity stake in the United States. And they're not an act of charity, either. They're a roundabout way of taxing Chinese farmers, pensioners, and service sector workers in order to subsidize the export sector. Some Americans benefit from this, other Americans suffer, but given the paralysis in congress and the FOMC, it seems clear at this point that we would benefit on net from them buying less debt.

Bill Galston Discovers The Balance Sheet Recession

I have genuinely no idea why William Galston thinks the point that the mortgage-debt overhang is playing a huge role in the recession constitutes a "new" theory of the recession. But I'm not peevish, so I'll just say he's correct and we should talk about solutions:

It's time, then, to reexamine our housing policy from the ground up. If employers won't hire until consumer demand increases, and if demand won't increase until household balance sheets recover, then policymakers should focus on accelerating that recovery. Here's a back-of-the envelope calculation: If we need to return the household debt burden to where it stood before the bubble, we can either wait another four or even five years (which is what it would take at the current rate without additional intervention), or we can speed it up by allocating the losses of principal that lenders need to accept and remove from their books. Moving the household debt to disposable income ratio from 118 percent to the pre-bubble 100 percent implies a total debt reduction of roughly $1.5 trillion.

As I said yesterday, doing that might actually end up requiring more "bailouts" of institutions paired with firings of bank managers. Politically speaking, that's a hard lift.

This is one of several reasons why I believe that the best resolution would be to set a higher Nominal GDP growth target and clarify that the Fed is willing to accommodate Reagan-era levels of inflation if that's what's necessary to achieve it. Most mortgage debt, and a decent share of other debt, is denominated in nominal terms, so inflation accommodation would speed the process of getting people out from under debt overhangs. But unlike targeted mortgage relief, it would also help people (like, say, me) who have mortgages but aren't underwater. Last, such a commitment from the Federal Reserve would also encourage high net wealth individuals and cash-rich firms to reduce their holdings of safe low-yield assets and increase their purchases of real goods and services or riskier private business investments.

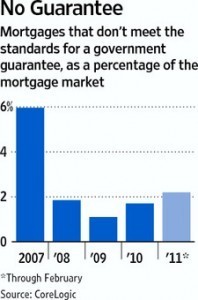

Unorthodox Mortgage Lending Making A Comeback

According to analysts, a handful of private investment firms have started making home loans to borrowers who fail to meet banks' requirements, which got tighter post-crash and have largely stayed that way. And for now they are holding them on their books, which is novel. At least two, Athas Capital Group, of California, and New Penn Financial, which is owned by Shellpoint Partners, of New York, are also making jumbo loans, or loans in most parts of the country that exceed $417,000, as the federal government appears to be scaling its support of that market.

The good news is that we're not going full-on crazy just yet:

The firms say this is far from the subprime lending of the go-go years. While they may embrace slightly riskier borrowers, they require higher down payments, around 40% on average at Athas Capital, compared with roughly 10% for a bank loan, says Keith Gumbinger, vice president at HSH Associates. And while they are willing to be flexible with income documentation, accepting a workplace pay stub or a series of bank statements in lieu of tax-return documents, they still require documentation as proof a borrower can repay the loan. This opens the door to otherwise qualified borrowers who have been foreclosed on, for example, or who may be self-employed or recently unemployed but are now back to work, says Chip Cummings, president of Northwind Financial, a consultant to mortgage lenders.

So far, so good. But if this works out, then presumably we'll push ever-further into new frontiers. The problem is that as long as we have a tax code that's heavily biased in favor of people taking out large loans to finance their own housing, then expanding the number of people eligible for such loans is an important kind of egalitarian measure. The right way to address this would be to curb the tax bias, but instead, everything in our politics tends to push toward expanding credit.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers