Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2241

July 15, 2011

Monetizing The Debt

CB asks:

I've seen some discussion on very liberal blogs about a possible way out of default called coin seigniorage. The advocates essentially want the Treasury to strike a 2 trillion dollar coin to pay debts and finance the country. Assuming this proposal of dubious legality (I'm no expert, but the advocates do put forward some law backed analysis) could be done, what would the effect on the economy be?

This is an idea that's circulating in Modern Monetary Theory circles, and I believe that it's legally mistaken.

That said, conceptually it highlights a very accurate point. If you think of the United States government as a consolidated entity, it's not possible for us to "run out of money" or "go bankrupt." The government of Ireland owes euros, but it lacks the legal authority to create Euros. Governments of small developing countries often owe dollars, but lack the legal authority to create dollars. Under a gold standard, a government might owe gold and lack the physical capacity to create it. But the United States is owed dollars, and can create dollars, so it's absurd to think that we might not be able to pay our bills.

Now what might happen is that people lose willingness to lend us dollars in the future. We also might have inflation. Money was lent in the past on the assumption that dollars would be able to purchase real goods and services. Monetization of debt would reduce the real purchasing power of dollars, and might call into question the wisdom of agreeing to lend dollars in the future. But these are different issues.

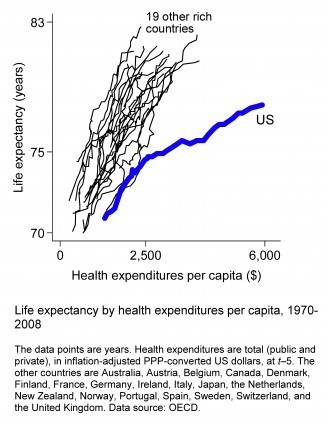

America's Health Care System Is Very Inefficient

Great chart from Lane Kenworthy:

I think the most charitable interpretation you can give to this is that the existence of an inefficient system in the United States acts as a subsidy to global health care innovation. With prescription drugs, for example, the availability of windfall profits in the USA attracts capital to pharma R&D. Then when the drugs are developed, they're sold abroad for something much closer to marginal cost. Still, even on this interpretation, we're doing something badly wrong. This is why CAP's deficit reduction plan (PDF) focused heavily on systematic reform of the health care system rather than narrowly shifting costs out of Medicare and Medicaid and on to states and patients.

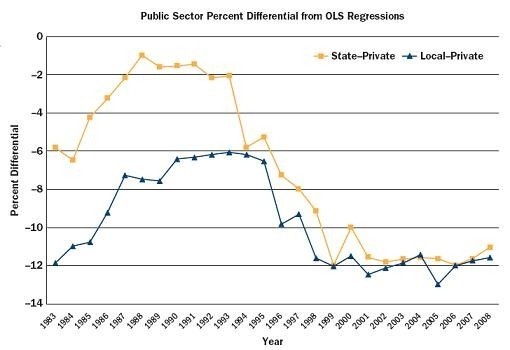

Is The Government Hiring Overqualified Workers?

Dylan Matthews tries to tackle the question of whether public sector workers are overpaid. He concludes that they're not:

Keith Bender and John Heywood, economists at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee, did a comparison of state and local and private sector compensation that controlled for age, education level, experience and other factors, and found that state and local workers are consistently underpaid, and have been growing more so since the early '90s.

The more I think about this question, the less sense I think it makes. In a competitive labor market, nobody is "overpaid." If one restaurant pays its line cooks more than another restaurant, it's presumably trying to get privileged access to higher quality workers. The question is whether or not public agencies are purchasing unduly high-quality labor. And that's not a question that it makes sense to ask in general. Baltimore probably should be investing more in obtaining the best police officers possible than Bangor. Doing statistical controls ends up sort of further obscuring this.

POTUS Wants A Grand Bargain, And The Fact That He Wants It Makes One Very Difficult To Achieve

Watching the press conference today, it was hard not to be struck by the extent to which Barack Obama really and truly wants a grand bargain on the deficit. One doesn't say this kind of thing at a press conference, but you could easily imagine him saying, "Look, Republicans, I agree with you — I want to enact steep cuts in spending, but to sell my base on it you need to throw me some tax hikes."

But here we get to the problem that's recurred throughout Obama's time in office. If members of Congress think like partisans who want to capture the White House, then the smart strategy for them is to refuse to do whatever it is the president wants. The content of the president's desire is irrelevant. But the more ambitious his desire is, the more important it is to turn him down. After all, if the President wants a big bipartisan deal on the deficit, then a big bipartisan deal on the deficit is "a win for President Obama," which means a loss for the anti-Obama side. When Obama didn't want to embrace Bowles-Simpson, then failure to embrace Bowles-Simpson was a valid critique of him. But had Obama embraced Bowles-Simpson, then it would have been necessary for his opponents to reject it. That's why now that Obama has a position well to the right of Bowles-Simpson, his opponents are still against Bowles-Simpson.

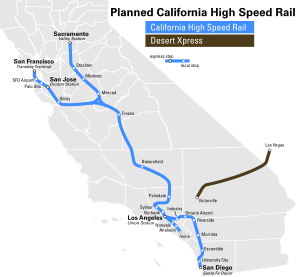

The Cost Of Hegemony

I was saying to someone the other day that I think we underestimate the long-term price the country pays for its drive for global domination by thinking too much about the flow of spending and not enough about the stock of missing goods. Consider, for example, trains.

Randal O'Toole from the Reason Foundation has dedicated his life to the principle that investing in rail is a costly boondoggle. He says:

Even though moderate-speed passenger trains are less expensive than true high-speed trains, they are still very expensive. Upgrading the 12,800 miles of track in the administration's plan to moderate-speed rail standards would cost far more than the $14.5 billion the president has proposed to spend so far. The entire 12,800-mile Obama-FRA system would cost at least $50 billion. Rather than build the entire system, Obama's plan really just invited states to apply for funds to pay for small portions of the system. [...] One cautionary note on high-speed rail costs comes from California. In November 2008, California voters agreed that the state should sell nearly $10 billion worth of bonds to start constructing a 220-mile-per-hour high-speed rail line from San Francisco to Los Angeles. The state's estimated cost for the entire system jumped from $25 billion in 2000 to $45 billion by 2008. However, one independent analysis concluded that the rail line would cost up to $81 billion.

Thus, the costs of a true high-speed rail system would be far higher than the costs of a medium-speed system on existing tracks, as envisioned by the Obama administration. To build a 12,800-mile system of high-speed trains would cost close to $1 trillion, based on the costs estimates of the California system. It is unlikely that the nation could afford such a vast expense, particularly since our state and federal governments are already in huge fiscal trouble.

The cumulative spending on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan has, thus far, been $1.4 trillion, and we haven't stopped spending money on either of those things. Keep in mind that this O'Toole estimate isn't the cost estimate of a rail booster. O'Toole's point is that rail proponents underestimate the cost of building these things and that $1 trillion is the real cost of doing it. Also keep in mind that nobody is proposing a system this expansive. O'Toole's point is that this is a reductio ad absurdum of rail proponents' idea. People think a high-speed rail initiative sounds like a good idea, but to really build a nationwide HSR network would cost (cue Dr Evil voice) ONE TRILLION DOLLARS.

And yet whether or not you think building a trillion dollar nationwide true HSR network would be a good idea, I think there's no question that if it existed, some people would get some use out of it. The money would be spent, and then we'd have the train. Operating costs would exist, of course, but they'd be trivial compared to construction costs. Which is to say that when you spend on rail infrastructure, you spend money but you accumulate a stock of trains and train tracks, etc. that can be used in the future. When you spend on the military, you don't much in the way of useful stock. You build a bomb, then the bomb blows up. Or else the fact that you have the military equipment becomes (as in Libya) the reason you need to spend more money on losing it. Or else good money gets thrown after bad, as in the situation where a president who thinks we never should have invaded Iraq now thinks we need to keep spending money on sustaining a presence there. The overall result is to slowly but surely impoverish the country. Meanwhile, if you look at how American became a major power in the first place, it had nothing to do with defense spending and everything to do with economic growth. If you have growth, then you can build a military. If you squander your resources, then you'll be overtaken.

Complacency Is The Right Attitude

Kevin Drum breaks ranks from the correct attitude of deficit complacency, citing Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff's argument that bond markets can turn on a dime:

Several studies of financial crises show that interest rates seldom indicate problems long in advance. In fact, we should probably be particularly concerned today because a growing share of advanced country debt is held by official creditors whose current willingness to forego short-term returns doesn't guarantee there will be a captive audience for debt in perpetuity. Those who would point to low servicing costs should remember that market interest rates can change like the weather. Debt levels, by contrast, can't be brought down quickly. Even though politicians everywhere like to argue that their country will expand its way out of debt, our historical research suggests that growth alone is rarely enough to achieve that with the debt levels we are experiencing today.

Like virtually everything I've heard Reinhart & Rogoff say since the publication of This Time Is Different, that strikes me as empirically accurate but irrelevant to the situation. I saw Sen. Rob Portman (R-OH) on TV earlier today darkly warning that absent sharp spending cuts, "interest rates will skyrocket, we'll have inflation, we'll have a decline in the value of the dollar." In an ideal world, the TV host would have pressed him and noted that there's no evidence for this in current financial markets. But he might have replied with the R&R point that this storm could come out of nowhere. But Portman's model here is of something like the 1997 East Asian crisis, or what happened to Iceland or parts of Eastern Europe back in 2007-2008. These are, however, structurally different situations.

In one kind of case, you have an economy operating near full employment, but with high debt levels (in either the private or public sector or both). Then a sudden loss of confidence causes an outflow of foreign capital. That pushes borrowing costs up, which is a drag on the economy. But at the same time, the value of your currency falls, which puts pressure on inflation so your central bank can't generate growth.

That's bad news. But it has nothing to do with the actual situation facing the United States. Virtually nobody in the United States has debts denominated in foreign currency, and certainly the U.S. government doesn't. What's more, we're not operating anywhere near full employment. If we experience capital flight and a declining dollar, what happens is that our debts get cheaper and easier to pay off, not tougher and more expensive. We'd face a very modest inflationary pressure (foreign-made stuff would cost more) but also a huge increase in real output since foreign demand for U.S.-made goods would skyrocket. The situation might be bad for rich creditors, especially foreign rich creditors, but from an overall national interest perspective, it would be more like the solution to our problems than the source of them.

None of that changes the reality that over the long-term the debt:GDP ratio needs to stabilize at some level. But there's not any current problem that can be traced to debt woes nor any prospect of such a problem materializing in the near term. Thinking about the long-term is great, but we're having severe present-day problems and it's smart to tackle issues in order.

Why Should The Character Of Streets Be Constant?

Historic preservation, as I used to understand the term, is about the idea that cities contain structures that are worth preserving. It might be more economically efficient to do strip-mining in the Grand Canyon, but aesthetically it would be a scandal. By the same token, you don't want to just tear down beautiful old buildings willy-nilly. The block that my office is on features a very nice old church whose space could probably be more profitably occupied by a boxy DC office. The case that the district should forego some economic benefit in order to preserve the aesthetic benefit of maintaining the church seems perfectly cogent, even if not persuasive in all cases. But in practice, an awful lot of what our Historic Preservation Review Board does seems to me to be quite different. They look not at old structures, but at proposals for new ones that happen to be near old structures. And then they issue decisions on the basis of the alleged principle that new things should all be made to resemble old things, and neighborhoods should always look the same.

So you get stories like this. The following decidedly non-historic structure is located inside a "historic district":

The owner wants to replace it with something like this:

Meh. But apparently that's what they want to do. And it's not like the loss of the Capital Carpeting building or Yum Carryout entails some kind of monstrous aesthetic loss. What's more, this is a great neighborhood. I used to live in the vicinity, but I don't anymore because I couldn't afford to live there without roommates. We should all applaud the construction of a sizable structure there that will increase the number of people who can enjoy this great community. But the HPRB says we can't because everything has to be the same forever:

HPRB asked architect Eric Colbert to redesign the project, with particular attention to the Wallach Street setback. HPRB chair Catherine Buell told me that the board felt this "will change character of this narrow street in particular," and that the board "has consistently ruled that buildings have to be set back."

David Alpert mounts the case that the "character" of the street will survive. But, really, what's the principle operating here? How did the street get to be how it is now in the first place? Surely not via rigorous enforcement of the rule that nothing is allowed to change.

Neighborhood busybodies Doug Johnson and Craig Brownstein who are against the project are at least more honest. They don't actually care about preservation or history or anything else. Instead what happens is that they currently enjoy access to public land at sub-market prices and they don't want to share that subsidized parking with other people. "Traffic whizzing down Wallach will increase," they whine, "and street parking (which is to say what barely exists now) will evaporate." It would be much healthier if we could actually debate these kind of issues within these kind of parameters rather than based on made-up aesthetic principles. Johnson and Brownstein's desire to maximize their access to government-provided subsidies and their hesitancy to share those subsidies with anyone else is very understandable. At the same time, the subsidized access to DC-owned land that they don't want to give up is being provided to them by the city as a whole. I live a mile away from there and don't benefit at all from giving Johnson and Brownstein privileged access to subsidized street parking. But I would benefit from adding more taxpaying members to the overall community. And obviously people like me far, far, far outnumber people like Johnson and Brownstein who currently enjoy cheap parking on that block. Indeed, the city's poor residents — the ones who really depend on public services and who seriously feel the pinch when the city needs to cut spending — are the ones who really lose out here in the quest for rich people to hold on to their subsidies.

Fun With Datasets

Via Tyler Cowen, an example of the kind of striking new research that we can expect more of as information technology and growing computer literacy make it ever easier for researchers to explore correlations.

Tatu Westling of the University of Helsinki reports:

This paper explores the link between economic development and penile length between 1960 and 1985. It estimates an augmented Solow model utilizing the Mankiw-Romer-Weil 121 country dataset. The size of male organ is found to have an inverse U-shaped relationship with the level of GDP in 1985. It can alone explain over 15% of the variation in

GDP. The GDP maximizing size is around 13.5 centimetres, and a collapse in economic development is identified as the size of male organ exceeds 16 centimetres. Economic growth between 1960 and 1985 is negatively associated with the size of male organ, and it alone explains 20% of the variation in GDP growth. With due reservations it is also found to be more important determinant of GDP growth than country's political regime type. Controlling for male organ slows convergence and mitigates the negative effect of population growth on economic development slightly. Although all evidence is suggestive at this stage, the 'male organ hypothesis' put forward here is robust to exhaustive set of controls and rests on surprisingly strong correlations.

Moral of the story: Empirical work is important, but you always want to see a strong theoretical basis for conclusions.

Breakfast Links: July 15, 2011

— Why has gender equity had so little impact on public restrooms?

— Charlie Gilmour don't need no education?

— Marine General Cartwright warns that defense cuts might lead to re-institution of conscription.

— NBA PA chief Billy Hunter says players should go to Europe if American teams refuse to hire anyone to play.

— On the very short term, fiscal contraction could make the deficit worse.

— Peter Wallison's scandalous behavior on the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission.

— Bob Kuttner on Fannie Mae.

— Debt ceiling crisis would plausibly bust political science models so it's hard to know how people will react.

— Chinese housing values.

— The Revolutionary War was an economic disaster.

July 14, 2011

The Fed Should Cut Interest On Excess Reserves

In his testimony before Congress, Ben Bernanke also got even more explicit about the fact that he has tools at his disposal to boost economic growth, tools he simply prefers not to use:

Even with the federal funds rate close to zero, we have a number of ways in which we could act to ease financial conditions further. One option would be to provide more explicit guidance about the period over which the federal funds rate and the balance sheet would remain at their current levels. Another approach would be to initiate more securities purchases or to increase the average maturity of our holdings. The Federal Reserve could also reduce the 25 basis point rate of interest it pays to banks on their reserves, thereby putting downward pressure on short-term rates more generally. Of course, our experience with these policies remains relatively limited, and employing them would entail potential risks and costs. However, prudent planning requires that we evaluate the efficacy of these and other potential alternatives for deploying additional stimulus if conditions warrant.

It's important to call a bit of BS on this business about "potential risks and costs," especially as applied to the paying of interest on excess bank reserves. The Federal Reserve system never did this until the fall of 2008. There's no scary economic risk involved in going back to the policies that we used successfully for decades. The interest on excess reserves policy was launched in the middle of the banking panic and has done nothing but exacerbate the subsequent recession.

Meanwhile, for some reason the president of the Dallas Fed thinks there's nothing more that can be done. He needs to pay more attention.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers