Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2237

July 19, 2011

The Distributional Impact Of Barber Licensing

In the comments to Henry Farrell's latest intervention into the debate over the need for a "theory of politics," I note that many people seem primarily to be interested in disagreeing with my public policy judgment. Since I, as Farrell notes, am much more comfortable debating policy specifics than hazy theories of politics I'd rather engage in this. In particular, one thing that came up is the old issue of barber licensing. I see breaking up the barber cartel and increasing competition for barbering services as a progressive measure, because if you reduce the cost of things that poor people buy, you increase their real living standards. A contrary view espoused in comments is that since barbering is a working class occupation, we ought to favor cartelization as a means of increasing working class income.

This, for the record, is exactly what I had in mind when in an earlier post I said that policy ideas need to be "workable." We need to ask ourselves if it's actually true that barber licensing is an egalitarian measure. I'm almost certain that it's not. Clearly, if we restrict entry into the barbering industry what we do is redistribute real income away from the customers of barber shops and to the incumbent barbers. In effect, you're setting a kind of price floor. But the important thing to note about this is that haircuts are already sold at a wide range of price points. Rich people — the kind of people it would be progressive to stick it to — are not buying the cheapest available haircuts. Indeed, they're not even close. And there's little reason to think that the de facto price floor on haircuts is having any impact whatsoever on the price that they pay for haircuts. The people impacted by the haircut price floor are going to be the people shopping for the cheapest haircuts. That, by and large, is going to be relatively low-income people.

But to perhaps gesture at a "theory of politics" issue, I think part of what bugs people about the barber issue is that they've developed the implicit view that for progressive politics to succeed we need to raise the social status of "big government," and that it's counterproductive to this mission to highlight any misguided "big government" initiatives. It's acceptable to criticize excessive spending on the military and on prisons, because the conservative critique of "big government" often exempts those institutions. But if conservatives attack "regulation," then "regulation" must be defended or, when indefensible, ignored. My view is that this is backwards, and that the public is skeptical about supporting "big government" precisely because they doubt that its advocates are invested in ensuring that higher taxes will lead to quality services. Progressive insouciance about the question of whether or not regulations are, in fact, serving the public interest feeds cynicism about the role of the state.

Reducing Objective Scarcity

Another word on the Heritage Foundation's ever-ending effort to persuade us that poor people aren't really poor because electronics are cheap. It's worth noting that though this fact hardly proves what Heritage is saying it proves, it obviously is true that the reduced price of electronics is a real benefit to people that improves their lives. And the reason that this works is that electronics aren't scarce. Televisions aren't made of diamonds, so even though state-of-the-art TVs are expensive, there are always plenty of old models around to be found for very little money.

But lots of things are scarce in America. Adam Serwer that "it doesn't really matter if the neighborhood is safer and nicer than it used to be if you can't even afford to stick around and enjoy it." That's a reminder that what we want out of the world isn't just for some neighborhood or other to become safer, but for more people to enjoy life in a safe neighborhood. That can be achieved through two kinds of actions. One is by taking not-so-safe neighborhoods and making them safer. But the other is by increasing the quantity of houses that exist in any given safe neighborhood. In general, if you care about equality, you ought to be passionate about scarcity. As long as there's not enough of some valuable commodity to go around, then whoever's richest is going to end up getting it even if the income distribution is relatively flat. By contrast, when you make some category of goods plentiful, you necessarily end up curbing inequities. These days all kinds of Americans can afford a good television. Tragically, though, many Americans can't afford a house in a safe neighborhood with a decent school that's within a convenient commute of the central business district of a major city.

FDR: Rhetoric And Reality

I've seen this video of FDR campaigning in 1936 making the rounds:

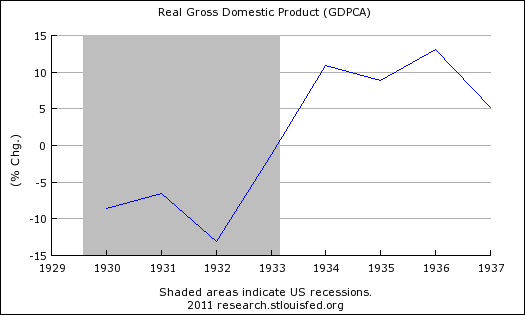

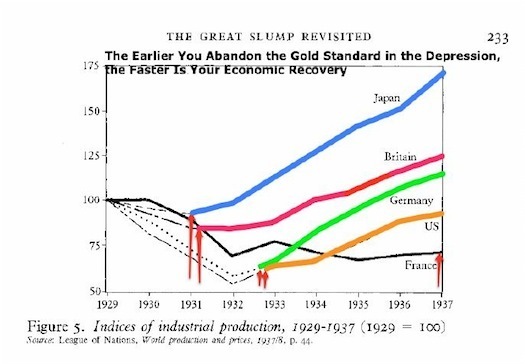

A lot of progressives think this is the kind of rhetoric Barack Obama needs to deploy. I like the speech, personally, but as I always want to remind people, FDR's incredible popularity was built on the back of incredibly rapid economic growth:

I feel fairly confident that if Obama had been delivering these kind of results, he'd have pretty stellar ratings with just about any plausible rhetorical approach.

Eugene Fama's Syllogism

Via Paul Krugman, Eugene Fama offers a syllogism on macroeconomic stabilization:

Again, here is my argument in three sentences.

1. Bailouts and stimulus plans must be financed.

2. If the financing takes the form of additional government debt, the added debt displaces other uses of the same funds.

3. Thus, stimulus plans only enhance incomes when they move resources from less productive to more productive uses.

Are any of these statements incorrect?

In his attack on me Krugman implicitly assumes that sentence 3 above is true; that is, the stimulus plan will on balance move resources from less productive to more productive uses. This is indeed the focus of the issue.

One way to understand what's wrong with this is to consider the circumstances under which it might be true. Suppose that we were living in the Kingdom of Coneria and "funds" meant "gold coins." In that case, anything the government does to stimulate the economy requires the acquisition of additional gold coins. You could borrow the gold coins, you could tax the gold coins, you have options, but somehow you've got to get the coins. In this case, due to the objective scarcity of coins the only real issue is whether you're shifting the coins from a low-efficiency use to a high-efficiency one.

But now suppose you swap everyone's coins for little pieces of paper with the king's face on them. Just as before, economic actors need a medium of exchange. And just as before, taxes are due. But instead of paying taxes with gold coins, you pay them with little pieces of paper. This makes the pieces of paper commodities worth having, and thus convenient for use as a medium of exchange. Now the king is riding around one day and he notices that 9.1 percent of the population is unemployed. He also sees that there's a bridge in disrepair. So he prints up some more little pieces of paper, walks over to some unemployed dudes, and says, "I'll give you some paper if you fix the bridge." The dudes are short on little pieces of paper, so they jump at the opportunity. This use of pieces of paper doesn't need to be more efficient than some alternative use of the paper. You just had the paper printed. All that has to happen is that it has to be more efficient for the dudes to be building a bridge than for the to be sitting on the couch scouring the help wanted ads and feeling depressed.

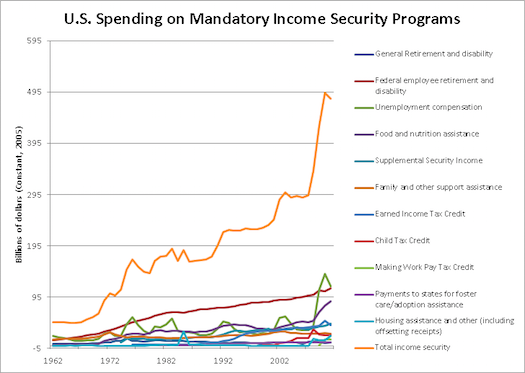

Income Security Spending In The United States

To further make the point that I don't see any particular reason to believe that a political agenda centered in part on increasing the incomes of low-income people by giving them more money is somehow obviously doomed, here's a chart of historical US spending on programs the Office of Management and Budget construes as "income security" programs:

The last spike obviously looks to have been produced by the recession. Still, the historical pattern here is of a punctuated equilibrium. Occasional sharp upward jumps that are partially rolled back followed by a new plateau. I suspect that the increases associated with the 110th and 111th Congresses will, likewise, be partially rolled back leaving real transfer payments to the poor substantially higher than the pre-Pelosi level. Similarly, the Affordable Care Act should substantially increase the volume of financial resources directed at the bottom third of the income distribution even after inevitable modifications.

I don't think this should be the exclusive progressive political goal. But I don't think people should be quick to dismiss its value or its viability.

The Conservative Alternative To Progressive Neoliberalism

Ta-Nehisi Coates, responding to me on the case of a Washington, DC landowner "forced" to sell her property because her investment has massively increased in value and she now needs to pay high taxes on it does, I think, hint at a real alternative to progressive neoliberalism:

I actually think it's fairly easy to understand Johnson's beef. She likes her neighborhood as it is. She may well be able to "sell high," but the fact is she doesn't want to sell at all. She probably would love to see her property values rise, but the neighborhood isn't simply, for her, a financial instrument–it's an emotional one. In that sense, Johnson isn't very different than millions of other humans who invest in neighborhoods.

Her contention that the city is "driving us out of here." is very much debatable. But it's worth noting that a class of owners with a commitment to something more than a naked financial return is a good thing. When Matt asserts that the city is trying to make H Street a "desirable place to live," I am compelled to ask "desirable for whom?" I'm not being obtuse here–I understand, in the aggregate, his larger point. But very often people find a kind of value in their living condition that eludes socioeconomic data.

That makes perfect sense. But I do think it's worth saying that the alternative being put on the table here is a conservative one, and the mere fact that the successful investor who doesn't like high property tax rates is black doesn't change that fact. After all, what concrete policy steps could the DC government take to avoid more people being stuck with the problem of rising property values that lead to higher property taxes. Well, I see two:

1. The city could stop investing in improved public services and public safety.

2. The city could reduce property taxes, especially on well-heeled property owners.

That's not a wild-eyed or insane policy agenda by any means. Indeed, it's the fiscal agenda of New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie and New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo. And I think it's good for progressives to pay attention to things like Johnson's story, since she can perhaps help people to better understand why an agenda of spending cuts and property tax cuts can appeal to a broad group of people and not just a tiny cabal of Koch-funded conspirators. That said, here in the DC context, we should recognize this kind of communitarian critique of liberalism for what it is — a conservative critique.

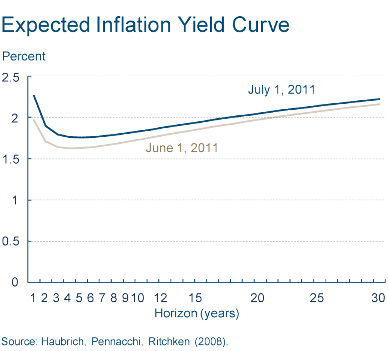

Checking In With The Yield Curve

Market expectations of inflation:

And the yield curve:

If I'm reading that correctly, that means negative real yields on everything less than five years. In other words, cheaper to finance the government with relatively short term debt than to finance it out of tax revenue. Naturally, DC is talking debt reduction.

Poverty Is Mostly About Housing, Health Care, And Education

The Heritage Foundation is out with the latest version of its annual poor people aren't poor because electronics are cheap report:

A serious person would follow this up with a discussion of relative prices. Over the past 50 years, televisions have gotten a lot cheaper and college has gotten a lot more expensive. Consequently, even a low income person can reliably obtain a level of television-based entertainment that would blow the mind of a millionaire from 1961. At the same time, if you're looking to live in a safe neighborhood with good public schools in a metropolitan area with decent job opportunities you're going to find that this is quite expensive. Health care has become incredibly expensive. The federal poverty line for a family of three is $18,530 a year. I wonder how many Heritage Foundation policy analysts are deciding they want to cut back and work part time because it'd be super easy to raise two kids in DC on less than $20k in salary? Perhaps just an outfit full of workaholics.

If Not Eurobond: What?

Tyler Cowen mounts some convincing arguments as to why a German taxpayer wouldn't want to find himself on the hook for some newfangled eurobonds as part of a eurozone wide consolidated fiscal structure. And I agree. There's absolutely no reason you would want to do this. Unless, that is, you had a deep-seated ideological commitment to a highly ideological project of European integration.

Do German voters have such a commitment? They certainly don't seem to. And yet the monetary union itself is precisely a highly ideological project of European integration. As brass tacks practical economic policy, it didn't make sense in 1999 and it doesn't make sense in 2011. It was vulnerable to failure in precisely the way that it's currently failing, and it was known to be vulnerable to this failure at the time it was launched. As I recall, on this side of the Atlantic, most economists warned Europe not to do this. But they did. Presumably for ideological reasons. But if you're in for the project, then you've got to be in for the steps to make the project workable and that seems to me to mean some kind of eurobonds. You can almost imagine Helmut Kohl and François Mitterand leaving a note in some office in Bonn below a sign that says, "Break glass in case asymmetrical macroeconomic shocks lead to Eurozone sovereign default risks." The note says that you can't have an enduring monetary union based on budget rules alone. You either need to ditch the project, or you need to move forward with the project.

Ever closer union is not just a slogan, it's a threat.

The Power Of Expectations

Doug Henwood returns to our basic disagreement about monetary policy:

I really don't know what he expected the Fed to do. Just before the Lehman crisis, the Fed held about $900 billion in assets. (See first column, here.) Within weeks, it held over $2 trillion. Now, it's close to $3 trillion. They bought all kinds of stuff, guaranteed trillions more. They cut interest rates to zero and made it clear they'd stay there for a long time. They did it in a secretive and unaccountable way, but they can hardly be accused of passivity. Would it have made a big difference if they'd said, "Gosh, we wish inflation would rise to 3%"?

My claim is that, yes, it would have made a difference if the Fed said, "We're happy to let inflation run 3-4 percent for several years until we get back down to something like full employment." At the margin, the higher inflation rate would have inspired cash-rich firms to expand operations rather than sit on the money. At the margin, the higher inflation rate would have inspired cash-rich individuals to buy stuff rather than sit on the money. At the margin, the higher inflation rate would have speeded the process by which indebted working- and middle-class Americans discharge their mortgage debts.

It's important to recall that it's not just me saying this. According to Ben Bernanke, a 3 percent inflation target would produce jobs and increase real ouput, but he doesn't want to adopt one because "[t]he anchoring of inflation expectations is a hard-won success that has been achieved over the course of three decades, and this stability cannot be taken for granted." That, to me, is a terrible reason for millions of people to be languishing in unemployment.

Now conversely, imagine that the Fed is happy with the level of inflation that we have right now, but by some miracle, the Congress decides to spend a huge sum of money on a giant program of public investment. Well, if it's well designed, the stimulative impact will mostly be mobilizing idle resources. But there's no way you could design a program of that kind that exclusively mobilizes idle resources. With income higher, there's bound to be some increase in demand for scarce resources — oil and gasoline, most notably, some other commodities, maybe a few forms of specialist labor, etc. That's going to lead to higher prices. Except that since the Fed doesn't want to allow higher prices, they'll tighten the money supply to counteract the impact of fiscal policy. Now we're getting nowhere. The fiscal expansion can't work unless the monetary authorities in some sense want to cooperate with it.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers