Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2238

July 19, 2011

Bad News For Lamb Fans

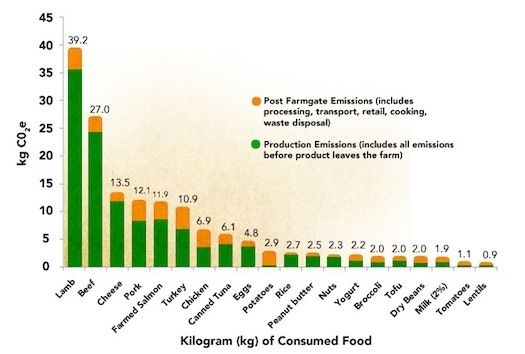

I've long felt that the American consumer's aversion to lamb was slightly odd. It's got a more delicious flavor than beef, in my opinion, and sheep are generally raised in more humane conditions than other mass market animals. Unfortunately, lamb turns out to be an ecological catastrophe:

That meat in general is bad news, climate-wise, is familiar. But it's interesting what a big gap there is. The carbon gap between lamb & beef on the one hand and pork & chicken on the other is larger than the gap between between pork & chicken and vegetarianism.

Breakfast Links: July 19, 2011

— The sharing economy.

— Like President Obama, I can never get a universal remote control to work.

— Bill Clinton says he'd use the 14th Amendment option.

— It sounds insane, but I've come to believe that Section 31 § 5112 clause (k) of the US Code authorizes Tim Geithner to mint platinum coins in any quantity and denomination he wants and get around the debt ceiling.

— Pass the popcorn as the UK Parliament questions Rupert Murdoch.

— As I said on Twitter yesterday, this would be a great time for George Soros to launch his hostile takeover bid for News Corp.

— Borders heading into liquidation as absolutely everyone refuses to buy the company.

— Shockingly, Richard Cordray is gonna get filbustered.

— 53 percent of self-identified Republicans think there's no problem if we don't raise the debt ceiling.

— Dwight Howard says he's considering playing abroad. He should go.

— Learning, signaling, and the economic rewards to college for professional basketball players.

— A consumer bust is a natural consequence of the prolonged wage bust.

July 18, 2011

The Case For Leisure

Juliet Schor argues for shorter working hours as a cure for recession blues:

Historically, market economies have absorbed this displaced labor in two ways. The first is the creative of jobs in new industries making new products. The 20th century brought automobile workers, higher education administrators and medical personnel. But new jobs, spurred on by growth in GDP, are only half the story. The other mechanism for maintaining balance in the labor market has always been reductions in hours of work. Without the advances of a shorter workweek, vacation time, earlier retirement and later labor force entrance, the economies of the OECD would never have attained the "golden age" of high employment that prevailed after the1930s depression. Between 1870 and 1970, hours of work fell roughly in half. These countries have re-balanced the labor market by re-distributing work to make its allocation fairer. We need shorter hours because it is unrealistic to count on growth in GDP to absorb all this current and future "surplus" labor. Rich countries just never grow that rapidly. So the austerity economics that says work longer and retire later has it exactly wrong.

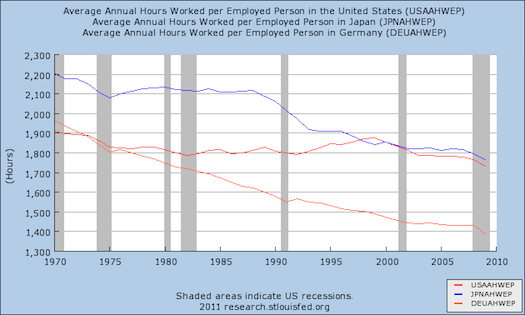

I think this is right in a big picture sense, but wrong as applied to the specifics of the recession. Consider the international data:

I think it's sensible of the Germans to have taken a lot of the gains from their increased productivity in the form of reduced working hours. But if you look at the German line in detail, you see a cyclical element. Each time a recession ends, it's associated with an uptick in hours worked. That's because you do recover specifically from a recession through an increase in the demand for labor that expresses itself first in longer hours and then in less unemployment. Then, in Germany at least, the underlying trend toward less work and more leisure comes back into play.

Which is to say I like Schor's ideas as a vision of the long-term future of the economy, but for the short-term we're still just looking for more demand.

The Fate Of The Safety Net

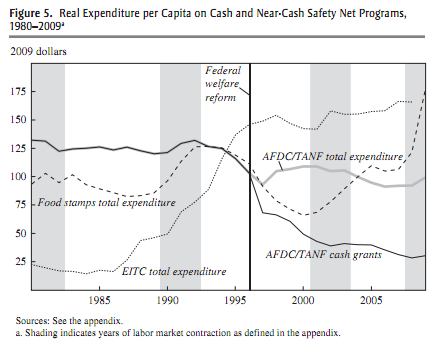

Relative to the issue above, I wonder if there's evidence that tax-and-transfer programs really have become politically unsustainable in a neoliberal era? There are probably lots of different ways you could look at this issue, but at a minimum this paper from Marianne Bitler and Hilary Hoynes (PDF) on what actually happened after welfare reform suggests that there actually hasn't been much change in total fiscal commitment:

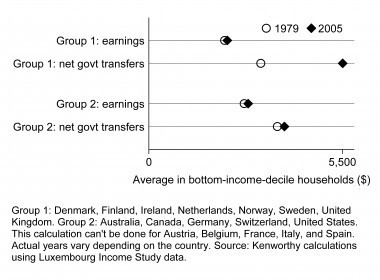

Another way of looking at this is internationally. According to Lane Kenworthy, market incomes for the poor have stagnated across the developed world, but in some countries transfer payments have risen and living standards increased:

This seems very sad to me. Poor Americans could enjoy substantially higher living standards if we did more to enact transfer payments that ensure that the fruits of economic growth will be broadly shared. In some countries, a lot of that happened, and in other countries very little of it did.

What Is The Alternative To 'Neoliberalism'?

The fact that Doug Henwood disagrees with me about monetary policy has suddenly turned into a sprawling cross-blog discussion of "neoliberalism" and its discontents. Personally, I find the argument to be infuriatingly devoid of content, but here's Henry Farrell's core claim, devoid of examples:

Neo-liberals tend to favor a combination of market mechanisms and technocratic solutions to solve social problems. But these kinds of solutions tend to discount politics – and in particular political collective action, which requires strong collective actors such as trade unions. This means that vaguely-leftish versions of neo-liberalism often have weak theories of politics, and in particular of the politics of collective action. I see Doug and others as arguing that successful political change requires large scale organized collective action, and that this in turn requires the correction of major power imbalances (e.g. between labor and capital). They're also arguing that neo-liberal policies at best tend not to help correct these imbalances, and they seem to me to have a pretty good case. To put it more succinctly – even if left-leaning neo-liberals are right to claim that technocratic solutions and market mechanisms can work to relieve disparities etc, it's hard for me to see how left-leaning neo-liberalism can generate any self-sustaining politics.

Having read this and various people agreeing with it, I have no idea what it is that we're disagreeing about. Neoliberals on this telling, favor progressive taxation. Non-neoliberals criticize this agenda as not politically workable in the long-term. And they counterpose as their alternative, more workable agenda, . . . what? Kevin Drum offers this effort:

I don't know the answer either. But as I said a few months ago, "If the left ever wants to regain the vigor that powered earlier eras of liberal reform, it needs to rebuild the infrastructure of economic populism that we've ignored for too long. Figuring out how to do that is the central task of the new decade." It still is.

So I really, strongly, profoundly agree with this. The moment someone comes up with a workable idea on this front, please sign me up. But if there's no idea to debate, then there's no idea to debate. Debating the desirability of devising some hypothetical future good idea seems kind of pointless to me.

This is too bad, because I think Henwood and I actually started out with a reasonably concrete disagreement on an important point. I think that better monetary policy, though hardly the solution to all of America's ills, could do a lot to reduce unemployment. His view seems to be not just that a more thorough economic restructuring would be desirable, but that it's strictly necessary to achieve recovery. In my view, that's factually mistaken. Better monetary policy over the past several years would, I believe, have produced a much shallower and shorter recession and left progressive politics with a much stronger hand to play on all kinds of other questions.

Political Patronage in Higher Ed Could Derail Attempts at Reform

By Matthew Cameron

Perhaps the most important thing to come out of the National Governors Association annual conference last weekend was a report on higher education that highlighted ways to achieve efficiencies at a time when public university systems are facing severe budgetary constraints as well as increased demand for their services.

Improving efficiency in higher education is crucial to long-term economic growth in the U.S. Therefore, it's encouraging to see governors taking the issue seriously and advocating the use of enhanced metrics to guide funding decisions and to measure student outcomes so that cost-effective universities can be rewarded through the state appropriations process.

Crucial to the success of this approach will be university boards of regents, which will have to shoulder much of the responsibility for designing appropriate metrics and implementing effective policies that improve institutional performance. Unfortunately, regents usually aren't appointed on the basis of their academic experience or policy-making prowess. Rather, as this Richmond Times-Dispatch makes clear, governors tend to hand out these positions to those who contributed generously to their election campaigns:

At least four of Gov. Bob McDonnell's recent appointees to boards of visitors of state colleges or universities donated $10,000 or more recently to McDonnell's Opportunity Virginia PAC.

Two other appointees are wives of major donors.

McDonnell announced 52 appointments to the public institutions July 1 and three more Friday.

University of Virginia political commentator Larry Sabato said it is not unusual for Virginia governors to make such appointments.

"It is not a shock to anybody that these key contributors have an advantage for these plum positions," he said.

Indeed, records of the Virginia Public Access Project, a nonpartisan tracker of money in state politics, show that former Govs. Timothy M. Kaine and Mark R. Warner also appointed major donors to college boards.

Virginia is hardly the only state where board appointments are given out as political patronage. A recent survey by the Knoxville News Sentinel found that appointees to the University of Tennessee Board of Trustees had donated an average of $8,273.41 to the campaigns of Don Sundquist and Phil Bredesen, the state's past two governors.

In fact, sometimes the political meddling goes even further. Earlier this year, South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley removed a member of the University of South Carolina board in the middle of her term and filled her seat with a major campaign donor. And Iowa Gov. Terry Branstad is under fire for forcing the resignation of two members of the Iowa Board of Regents and promptly replacing them with political allies.

Using the spoils system to determine the leadership of what are supposed to be among the nation's most meritocratic institutions has looked bad symbolically for a long time. Now, however, governors must face the reality that if they want university regents at the head of higher education's transition to the 21st century, they no longer can appoint them according to practices from the 19th century.

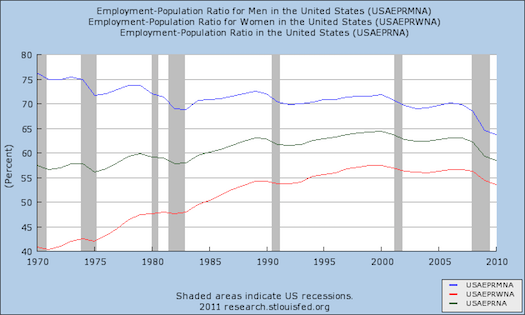

Employment And Population In The Long-Run

In the short-run, it's easy enough to see what's happening with the employment-population ratio in the United States. We're in a giant recession, so it's heading down. The longer-term picture is, I think, more ambiguous:

For a long time, women's employment has been rising while the trend has been for men's employment to fall. Up until 2000, the rate of women's increase was faster than the rate of men's decrease, so the overall trend was up. But since the demise of Pets.com, we've been on a downward trend. What's not clear is to what extent that trend is purely an artifact of the current downturn versus to what extent it may reflect an actual reversion to a pre-1990s equilibrium. From a progressive feminist point of view, we're presumably looking for men's and women's labor force participation to converge over the long run. But I'm not sure there are any obvious ideological grounds on which to favor convergence at one particular level over another.

Italy's Made In Frankfurt Bond Crisis

With the Eurozone debt crisis spreading to perhaps include Italy, it's crucial to understand that this particular aspect of the problem is "Made In Frankfurt." Made, in other words, by the European Central Bank. The reason is that though Italy has a high level of outstanding debt, it's also been running what's called a "primary surplus" for years. That means that the government is taking in more in tax revenue than its spending on services and transfers. There is a budget deficit, but the deficit is caused entirely by the need to pay interest on the outstanding debt. This means that the rate of nominal Italian GDP growth is crucial. If nominal growth is high, then the debt:GDP burden will shrink over time from its high level. But if nominal growth is low, then the debt:GDP burden will spiral upwards unsustainably.

Wolfgang Münchau says it's "hard to comprehend why markets decided to panic over Italy at this particular time." But I don't think it's hard to comprehend at all. The European Central Bank raised interest rates on July 7, reducing NGDP growth throughout the Eurozone, and a week later the world's eighth largest economy was facing an interest rate spike. Greece is insolvent under any scenario. Italy, by contrast, is perfectly solvent if and only if the European Central Bank allows for a recent level of Italian NGDP growth. But in order to contain inflation in Germany, the ECB wants to push Italian NGDP to a low level. That will force Italy to implement austerity budgeting, but austerity merely leads to lower growth unless it's offset by lower interest rates. But austerity can't be offset by lower interest rates if the European Central Bank insists on responding narrowly to conditions in Germany.

But no favors are being done to Germany with this approach. Germany is bigger and richer than Italy, but it's not that much bigger or that much richer. There's no containing a crisis that gets to Italy.

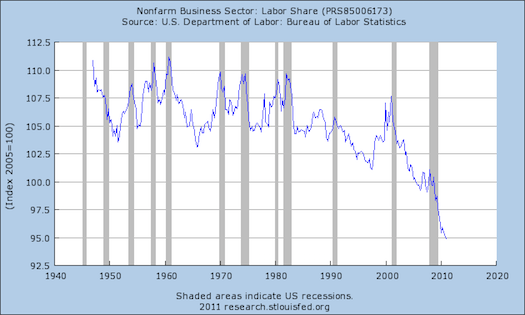

Unshared Sacrifice

David Frum asks:

Two questions for the Republican presidential candidates:

1) Is this a problem?

2) If yes, what can be done about it?

Of course Democrats should address it as well. I see two concurrent things happening here. One is the failure of policymakers to manage the business cycle adequately. The labor share of national income is a highly cyclical phenomenon. When a recovery from a recession begins, what happens is that firms have market opportunities and low labor costs. That leads to high profits, which lead to new investments, which reduces the unemployment rate. Then when the unemployment rate is low, the labor share of income grows. In the period before the 2001 recession when we had full employment, the labor share of income was healthy. Had the elites charged with management of macroeconomic policy succeeded in maintaining full employment, we wouldn't have this problem.

The second thing has to be the entrance of hundreds and millions of poor people from the developed world into the global labor market, right? In the aggregate, this has produced large benefits. And the appropriate policy response would have been something like a big increase in the generosity of the Earned Income Tax Credit to ensure that everyone who works hard and plays by the rules shares in the gains. But instead we spent the 2000s enacting regressive tax cuts. And now that it's time to pay the piper for that, the focus is all on cutting spending. It's a hell of a raw deal.

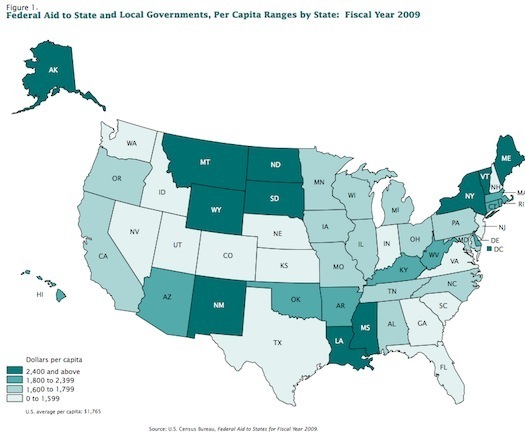

Which State Governments Lose If The Government Can't Pay Its Bills?

As Matt Cameron observed earlier this morning, a big part of the pain if the federal government can't pay its bills lands on state and local governments who get a lot of grant money from the federal government. Indeed, these grants are about 15-20 percent of federal spending in a normal year. When you factor debt service, the military, and programs for retirees out of the mix it, becomes a huge share of the remainder. This Census Bureau data is from 2009 (PDF) but gives you a basic sense of the shape of things:

"]

The big losers here are poor states (Mississippi), states with enormous Medicaid costs (New York), and what I take to be a block of tiny states who've leveraged their overrepresentation in the Senate (South Dakota, North Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, Vermont) into generous subsidies. Of course, the details really matter here. Medicaid is almost half of federal aid to state governments, so if that's somehow preserved, the distribution of the impact could end up looking quite different.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers