Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2234

July 21, 2011

Access to Fresh Produce Leads to Healthier Eating

By Matthew Cameron

Yesterday, The Washington Post reported Michelle Obama is teaming up with Wal-Mart, Walgreens, Supervalu, and a number of regional supermarkets to build stores in what are known as "food deserts," low-income areas that have little-to-no access to fresh fruits and vegetables. The logic behind this initiative is that it's tough for poor people to eat healthy if the only places in their neighborhoods that sell food are convenience stores and corner markets. Therefore, building supermarkets that are stocked with a variety of fresh produce ought to improve the health of the people who live in these neighborhoods.

Now, there's plenty of research out there that would appear to validate this assumption. This study, for example, found that people who live near supermarkets have better health outcomes than those who live closer to convenience stores or small-scale grocers. Another suggests that individuals who regularly shop at supermarkets consume more fruits and vegetables than those who purchase food elsewhere.

But arguably these studies are just showing that poor people are both unhealthy, and tend to live in neighborhoods that lack grocery stores. Would more supermarkets, as such, actually make a difference?

A study by Donald Rose and Rickell Richards of Tulane University comes closer to answering this question. It looks at whether easy access to supermarkets correlates to fruit and vegetable consumption. Importantly, the study's sample consists solely of food stamp recipients, who are overwhelmingly low-income. This controls for the various socioeconomic characteristics that confound the other studies. Additionally, the authors' calculations accounted for other factors such as nutritional awareness, employment status and parental status that could have skewed their findings. The result:

After controlling for confounding variables, easy access to supermarket shopping was associated with increased household use of fruits (84 grams per adult equivalent per day; 95% confidence interval). Distance from home to food store was inversely associated with fruit use by households. Similar patterns were seen with vegetable use, though associations were not significant. [...]

Nationally representative studies show that fruit consumption is low in the USA, with an average of only 1.5 servings consumed per person per day. Given this panorama, our results, suggesting a 1 serving size difference in fruit consumption due to store access, mean that store access is an important issue, even if only for the limited portion of the Food Stamp population with an access problem. While our results on the relationship of store access to vegetable consumption are less certain, the latter continues to be a dietary problem.

Obviously, improving access to fresh produce isn't a panacea for all of the disadvantages — time and budget constraints, lack of nutritional education, etc. — that the poor face. But Rose and Richards' report should encourage supermarkets and the Obama administration to press on with this initiative as a plank in the broader fight against health inequality.

The Right's Bad Romance With Tight Money

Tim Lee explores the question of why are libertarians such inflation hawks and can't find any good reasons:

Another likely factor is that American conservatism is a fundamentally populist movement, and the inflation hawks' position has a simplicity that makes it intuitively appealing, especially to a movement that tends to see all policy issues in terms of virtue. Rhetoric about "printing money," "debasing the currency," and so forth are not only intuitively appealing, they also dovetail nicely with broader conservative themes of thrift and self-control. The arguments of inflation doves are more subtle and lack the same kind intuitive appeal.

Until recently, the first factor largely explained my own thinking on the issue. I've long regarded the Fed's Friedman-inspired taming of inflation under Paul Volcker to be one of the great triumphs of libertarian ideas during the 20th century. But as the inflation I feared in 2009 has failed to materialize, I've begun to reevaluate my own reflexive hawkishness. It's not 1980 any more, and perhaps inflation is no longer the most pressing problem facing the Fed.

To give a non-psychological explanation that at least makes a little sense, this is what I think. Many pointy headed elites and business types have various policy reforms that they sincerely believe would boost economic growth on the supply side. They quite genuinely believe that lower social insurance benefits and reduced labor market and environmental protections will make almost everyone better off over the long run. But they're extremely pessimistic about the politics of persuading anyone of this. They see severe recessions as a moment when voters might be persuaded to swallow unpalatable reforms in the name of boosting growth. But this only works, however, is supply-side structural reform is turned into the exclusive legitimate means of boosting growth and employment. That, in turn, requires a kind of "demand denialism."

Doug Holtz-Eakin Explains Why You Need To Raise The Debt Ceiling

Pay attention tea partiers:

That's via Adam Ozimek. I note that it's actually a bit worse than DHE makes it out to be. If you shut down all discretionary spending, then there's nobody at the IRS to collect the incoming taxes and you end up needing to default on the interest payments anyway.

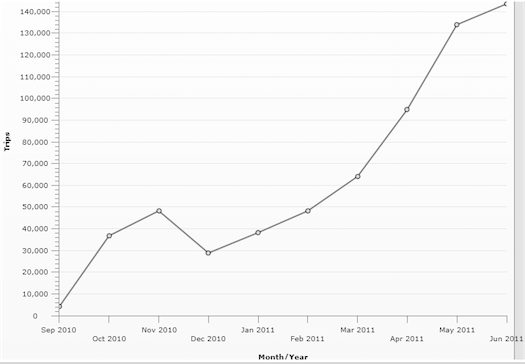

DC Bikeshare Growth Slows

Lydia DePillis brings us the chart:

June, that growth started to level off, and I'd be willing to bet that it plateaus in July, given the fact that it's been less than joyful pedaling lately. But if it stays at that baseline and just continues to increase again come crisp fall days (and continued system expansion) we could get a sense of the shape of things to come.

Maybe so. The interesting thing, to me, about bike share is the network effects. If we maintain a constant ratio of bikeshare members to bikeshare stations, then as the numerator and denominator grow the network as a whole becomes more valuable to each member. That should drive more people to become members, which means that in order to hold the ratio constant, we need more stations. And that, in turn, means that the network as a whole is more valuable. So if the city is able to keep building capacity, the sky should be the limit for growth notwithstanding the inevitable seasonality.

In Defense Of Chart-Reading

After making some very valuable remarks on gentrification in DC, Ta-Nehisi Coates makes a remark that I think slightly resembles me:

Looking back on this, the thing that strikes is the importance of journalism. I think it's really easy to become the sort of writer who reads reports from Brookings and analyzes charts and graphs, without ever having to talk to the people captured in the numbers. People are scary in a way that think tanks are not.

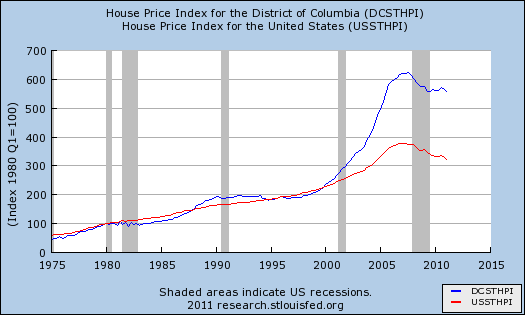

I don't actually think it's all that easy to be a data-driven guy in a narrative-driven profession. But I think narrative is vital, I'm just not the best guy to do it. At the same time, I firmly believe that data is really important to this conversation. For example, was the appreciation in DC housing costs in recent years just a phenomenon of the nationwide real estate boom, or is there a real underlying trend here? Statistical evidence confirms that DC has in fact grown more expensive at a much faster rate than the national average:

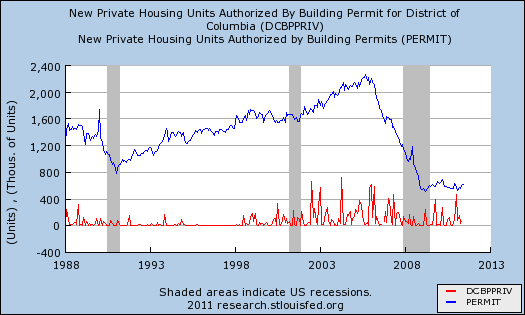

Now here's a chart comparing how many thousands of units worth of building permits were issued in any given month nationwide to how many units worth (no thousands) of new permits were issued in DC:

To me, these charts tell an important story. When I speak to people in the city (which in fact does happen, since I do live here, reporting aside), they often see the fact that new development occurs in the same places at times when housing costs are spiking. Consequently, they often reach the conclusion that new development is causing price increases and that the best way to moderate price increases is to moderate the pace of new development. These charts indicate, I think, that this is a mistake. That both new construction and higher prices are caused by higher demand for housing, and that DC is experiencing an above-average rate of housing cost increases because we're experiencing a below-average rate of issuing permits for new construction. Approximately one American out of 500 lives in DC, so for every thousand new permits issues nationwide you'd like to see two permits issued in DC. But we haven't been anywhere near that in a long time.

This fact — the great difficulty of getting permission to build new housing units in the city — is driving a lot of people's anxieties about housing affordability. But it's not a fact that's all that widely understood, and lack of understanding means the same problem keeps arising without it getting addressed.

In Financial Stabilization, Nothing Fails Like Success

Paul Krugman's The Return of Depression Economics quite smartly opens with an overview of a financial crisis that didn't create a huge economic slump, the 1994 "Tequila Crisis" in which a Mexican currency run turned into a bank run in Argentina but then everything was set straight by timely intervention by the Mexican, Argentine, and American governments:

Two years after the tequila crisis, it seemed as if everything was back on track. Both Mexico and Argentina were booming, and those investors who had kept their nerve did very well indeed. And so, perversely, what might have been seen as a warning instead became, if anything, a source of complacency. While few people laid out the lessons learned from the Latin crisis explicitly, an informal summary of the post-tequila conventional wisdom might have run as follows: First, the tequila crisis was not about the way the world at large works: it was a case of Mexico being Mexico. It was caused by Mexican policy errors—notably, allowing the currency to become overvalued, expanding credit instead of tightening it when speculation against the peso began, and botching the devaluation itself in a way that unnerved investors. And the depth of the slump that followed had mainly to do with the uniquely tricky political economy of the Mexican situation, with its still-unresolved legacy of populism and anti-Americanism. In a way you could say that the slump was punishment for the theft of the 1988 election.

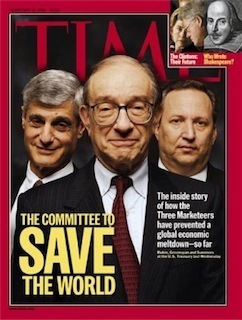

You can think of it as the "Committee To Save The World Problem." Insofar as your regulators' ad hoc efforts at crisis management succeed, everyone involved in the system tends to become more complacent and the system becomes riskier. People are often aware of the small sub-set of the problem known as "moral hazard," but what I think Krugman is pointing too here is the existence of a much broader issue. Even if the successful resolution of any particular financial crisis does entail severe punishment of wrongdoers, that doesn't change the fact that the press, the political system, the bureaucracy, the public, and the business community will all start to feel more complacent in ways that shape their decision-making. Regulatory success, as such, ends up changing the regulatory climate.

Fighting Lead Contamination With Fishbone Meal

The continued existence of toxic lead concentrations in many older urban neighborhoods is one of the really tragic aspects of American life. The evidence is overwhelming that lead is a serious public health hazard with quite severe social consequences down the road. But cleaning lead up is mildly expensive. Under the circumstances, almost anything we can do to either clean it up more cheaply or increase funding commitments to getting rid of it is very good. So it's very exciting to read that the EPA thinks they may have found a better way to get this done by using meal from the ground-up bones of inexpensive fish:

But now it is also coming to residential neighborhoods like South Prescott in Oakland, which this month became the first in the country where fishbone meal is being mixed into the soil for lead control under a project organized by the Environmental Protection Agency.

"It's fair to say, looking forward, that just about every urban residential area probably has a lead problem and we just can't afford economically and socially to move that amount of dirt any more," said Steve Calanog, the E.P.A. official in the San Francisco office that is overseeing the project. "Topsoil is a precious resource, and we don't have enough topsoil to replace it."

Although the agency does not record its spending by individual contaminants, it is safe to say it has spent millions of dollars on lead cleanup. If the new techniques of neutralizing toxic metals catch on the money would go further by replacing the method of digging up and disposing of hundreds of thousands of tons of soil that has been used for more than two decades.

Always nice to get a reminder that politics isn't just depressing stories and people acting crazy.

Let Richard Cordray Off The Leash

ThinkProgress Supreme Leader Faiz Shakir has a piece in the Washington Post arguing that unprecedented obstruction requires unprecedented tactics. Specifically, he argues that Barack Obama needs to drop the DC convention of having nominees suffer in silence meeting privately with legislators and let Richard Cordray speak:

After withdrawing his nomination earlier this year, Nobel Laureate Diamond was finally free to speak out. He took to the pages of the New York Times and appeared on MSNBC's "The Rachel Maddow Show" to bemoan the many misconceptions that had been advanced by Republicans about his record. It was a cogent and powerful response to his detractors. But it came too late.

It's time for a no-regrets approach. Richard Cordray shouldn't be quarantined from the media while Republicans go on the attack. This time, let the nominee speak.

I think this is especially compelling in light of the fact that at least 44 Senate Republicans have already indicate that they'll filibuster any nominee unless President Obama agrees to substantially restructure the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in order to make it more bank-friendly. Under the circumstances, we're not really talking about a narrow "confirmation strategy;" we're talking about a broader political strategy around the CFPB. Since Cordray would be the first chief of the new bureau whose very existence and basic structure are controversial, it makes a lot of sense for him to do media appearances where he can explain his vision for the agency in some detail and lay out his argument for the structure currently enshrined in law.

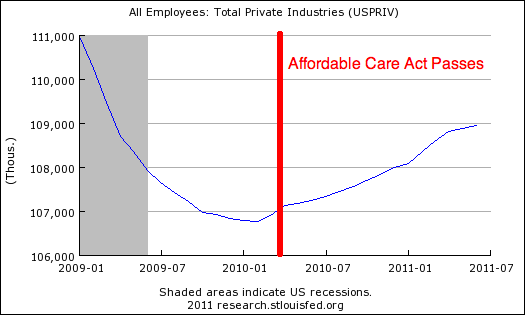

Having Plunged Previously, After The Affordable Care Act Passed Private Sector Employment Increased

I don't think this chart showing that private sector employment has grown after the passage of the Affordable Care Act really proves much one way or another, but it certainly proves that private sector employment has grown after the passage of the Affordable Care Act:

But the "math is hard" crowd at the Heritage Department has discovered that by taking the second derivative of employment you can create a "trend" that makes the ACA look bad:

It's very ingenious. And judged by my Twitter feed, there are actually some conservatives out there who are gullible enough to be taken in by this kind of thing. Clearly, though, no fair-minded person actually interested in the subject is going to be persuaded by this kind of nonsense. I think it's really too bad that conservative institutions spend a fair amount of time and energy on projects whose only possible effect can be to mislead their own constituency.

Proponents Of Non-Partisan Redistricting As A Cure For Legislative Polarization Need To Explain The Senate

Fareed Zakaria has a smart column highlighting the dysfunctional mismatch between America's highly polarized parties and our cooperation-oriented political institutions. Unfortunately, like a lot of people who write about this issue he seems to have fallen for the siren's song of redistricting as a cure all. He cites a Mickey Edwards article in The Atlantic as offering good ideas, including "truly open primaries and handing over the power of redistricting to independent commissions."

As it happens, we have a perfect controlled experiment in what an American legislature might look like without gerrymandering. It would look like the United States Senate. And the US Senate gives us plenty of examples of Senator-pairs who represent identical constituencies but have different partisan affiliations. So ask yourself, is it true that Pat Toomey and Bob Casey represent a streak of pragmatic dealmaking moderation that could get us out of this jam? How about Rob Portman and Sherrod Brown? What is true is that when you see a Republican elected from a clearly Democratic-leaning state like Scott Brown in Massachusetts, or a Democrat like Mark Pryor from Arkansas that this kind of "mismatched senator" tends to have a proclivity for dealmaking. But even so, the striking thing about partisan polarization in the United States is that Pryor has a more left-wing voting record than Brown just as Mary Landrieu is more left wing than Mark Kirk. Our null hypothesis about a House with less partisan gerrymandering should be that it would look more like the U.S. Senate. "Fair fight" districts would look like Ohio, schizophrenically sending us liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans according to circumstances prevailing on election day. Lopsided Republican districts would look like Arkansas, mostly sending us conservative Republicans but occasionally coughing up moderate Democrats. Lopsided Democratic districts would look like Massachusetts, mostly sending us liberal Democrats but occasionally coughing up moderate Republicans. But the moderate Republicans would still vote with the conservative Republicans most of the time, and the moderate Democrats would all be to the left of all the Republicans.

There are two main reasons why the parties are so polarized today. One is that we have the best-educated, best-informed electorate that we've ever had in American history, so elected officials are under more pressure to reflect the ideological views of their backers. The other is that we lack a major, high-salience issue that's uncorrelated with the main fights in American politics. In the middle of the 20th century, some economic populists were also white supremacists and some business friendly conservatives had progressive views on race and racial politics was very important to a lot of people. If something brand new (barbershop licensing, parking regulation, etc.) were to become highly salient that might cut across existing partisan divisions. But absent that, we need to accept polarization and find a way to make our institutions work.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers