Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2232

July 23, 2011

Norway And The Defense Budget

Jennifer Rubin proposes that the attacks yesterday in Norway are "a sobering reminder for those who think it's too expensive to wage a war against jihadists."

This of course would make no sense even if it were the case that the attacks were undertaken by jihadists as opposed to, say, anti-Muslim extremist Anders Breivik.

The Mayor of Oslo has, I think, the most sensible take of all arguing that "I don't think security can solve problems. We need to teach greater respect." I wouldn't go quite as far as he does. Security certainly can solve certain specific problems. Any country would do well to ensure that a relatively small number of high-value targets are hardened such that even a well-armed madman determined to commit mass murder can't get at them. But ultimately no security measure will provide absolute assurances against racist terrorist attacks, or jihadist terrorist attacks, or apolitical spree killings. The important thing is to keep the risks in perspective and to try to tackle social problems as best you can.

Strategic Air Power Still Doesn't Work

"It's getting more difficult to find stuff to blow up," said a senior NATO officer, noting that Kadafi's forces are increasingly using civilian facilities to carry out military operations. "Predators really enable you study things and to develop a picture of what is going on."

And yet the dream shall never die. Still, war after war it keeps being true that even though bombs and missiles are very good at blowing things up they're not very good at accomplishing political objectives.

New Study Suggests Food Deserts Require More Than Fresh Produce

By Matthew Cameron

After I wrote yesterday about a 2004 study showing that supermarket availability leads to greater fruit consumption among low-income individuals, my ThinkProgress comrade Amanda Beadle pointed out that a similar report was just released earlier this month. Its findings paint a more complicated picture of the "food desert" problem than did those of the Richards and Rose study I cited previously:

Fast food consumption was related to fast food availability among low-income respondents, particularly within 1.00 to 2.99 km of home among men (coefficient, 0.34; 95% confidence interval, 0.16-0.51). Greater supermarket availability was generally unrelated to diet quality and fruit and vegetable intake, and relationships between grocery store availability and diet outcomes were mixed.

This conclusion is important for a number of reasons. First, the study followed individuals throughout a 15-year period rather than taking a snapshot of their conditions at a specific point in their lives. This enabled researchers to compile a significant pool of data points and control for numerous confounding variables that could impact the progression of individual health over time.

Furthermore, the portion of the study dealing with supermarket availability used a more comprehensive measurement of diet quality than did the Richards and Rose study. The system is known as the Diet Quality Index, and it measures nutritional health based on individuals' success in meeting the daily recommended intake of certain food groups such as fruits and vegetables.

That is crucial because it means that while the report's findings don't necessarily contradict the Richards and Rose study, they significantly detract from the argument that expanding access to supermarkets is key to improving low-income dietary habits. Individuals who live close to supermarkets might consume more fruits on net than they would otherwise, but this might not be enough to significantly improve their health if they still aren't meeting the daily recommended intake of fruits. Additionally, fruits might not be the only thing people consume in greater quantities when they live near supermarkets — chips, soft drinks and dessert items also might find their way into individuals' shopping carts.

Finally, the report looks at the related issue of fast food availability among low-income individuals. It concludes that living near certain fast food establishments does, in fact, increase fast food consumption among low-income men. This further suggests that locating supermarkets in low-income neighborhoods might not be enough to improve overall health outcomes if individuals still live in close proximity to unhealthy fast-food restaurants.

July 22, 2011

No Deal

Once again, things fall apart in the debt ceiling talks. The way clear of this seems to me to be something like:

— Debt ceiling hiked by $2 trillion and paired with $2 trillion in spending cuts.

— House passes full extension of the Bush tax cuts.

— Harry Reid tries to bring extension of the middle class Bush tax cuts to the floor, but GOP filibusters.

— Bush tax cuts expire in 2012.

— Obama and GOP nominee fight it out in 2012.

This seems to me to achieve a substantive outcome better for progressives than the deal Obama is pushing for. At the same time in political terms achieves congressional republicans' goal of avoiding an affirmative vote in favor of tax increases, and avoiding letting Obama play the Grand Bipartisan Dealmaker.

If Only Milton Were Around…

Will Wilkinson posits that , hard money views might not have regained their currency on the right and the Federal Reserve might be in better position to deliver monetary stimulus.

Maybe so. That said, it's not as if the country lacks for Republican Party members who are also well-known Ph.D. economists with views somewhere on the New Keynesian-monetarist axis. Greg Mankiw's not dead, nor is Martin Feldstein. But these guys and other longtime GOP economic hands have largely been doing the usual Beltway wonk dance of speaking up for Republican positions when they agree with them, and staying quiet when they don't. You don't even need to see this as a particularly cynical way of behaving. In Washington, it's ultimately a question of all power to the politicians. A wonk who insists on picking fights with prominent party leaders just finds himself marginalized. Next thing you know and you're Bruce Bartlett. It's arguably more useful to just keep your head down and make sure that if your team takes over they have some sensible people to turn to.

I think it's especially difficult to be an advocate for monetary stimulus when the party you prefer is out of power. After all, it kind of seems like cheating. Here's President Obama implementing tax policies you don't like, health care policies you despise, and environmental policies you deem misguided. This is all stuff that you think will seriously impair jobs and growth over the long-term. Meanwhile, more or less by coincidence a shortfall in aggregate demand has created elevated unemployment and is making him unpopular. If AD stays too low, he's likely to lose and his policies will be reversed — saving the country from a long-term drag on growth. Alternatively, the Fed could ride to the rescue with five or six years of Reagan-era inflation and ensure that Obama's policies are entrenched. Sure that would help growth in the short-term, but there'd be a high long-term price to pay. So why contradict the Paul Ryans and Michele Bachmanns of the world when they run around complaining about currency debasement? I'm not sure a living Friedman's calculus would be that much different.

Wishful Thinking On European Employment

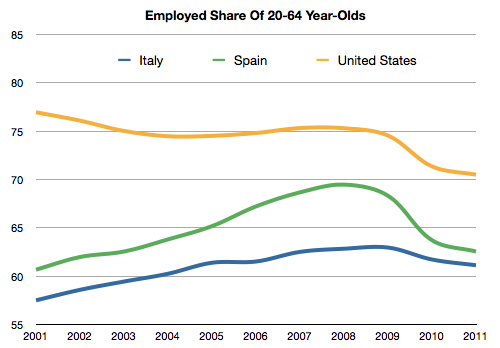

For a window into exactly how unrealistic vague aspirations for faster growth in the Eurozone periphery are, it's worth looking at the hazy statement the European leaders made on this subject in yesterday's declaration. Specifically, they swore that "[w]e will implement the recommendations adopted in June for reforms that will enhance our growth." The recommendations in question can be found in the Europe 2020 document and include as just one prong of the program each country's solemn commitment to achieve a "75% employment rate for women and men aged 20-64 by 2020– achieved by getting more people into work, especially women, the young, older and low-skilled people and legal migrants."

Note that the European Union doesn't so much as publish data on the 20-64 employment-population ratio. But fortunately Matt Cameron was able to piece it together for a few key countries based on the breakouts the OECD tracks. Here's a comparison of the United States with Italy and Spain:

Spain had a smaller share of its population employed at the business cycle peak than the Untied States had at the business cycle trough. Italy had an even smaller share than that employed. This reflects, among other things, southern European attitudes toward family and child-rearing that, like them or not, are unlikely to simply vanish with the wave of a Eurocrats' wand. And yet somehow we're expected to believe that Italy can undertake some kind of labor market reform that will allow it to attain the level of employment that the United States had at the business cycle peak in the face of both fiscal and monetary contraction. How's that supposed to work? And who seriously wants to bet on it happening?

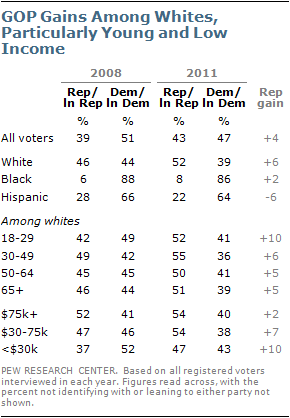

GOP Making Strong Party ID Gains Among Whites

For a long time the conventional wisdom has been that as the Hispanic population grows, the Republican Party will need to gain more appeal to voters outside its non-Hispanic white base. Logically, the alternative has always been to just do even better among white voters, just the way that Republicans regularly win elections in Mississippi despite its large and heavily Democratic black population.

The latest Pew data on party identification shows scenario two playing out with Republicans losing ground among Hispanics but posting strong gains with white voters:

Notably, the gains were particularly large among two sub-sets of white voters who hadn't previously had warm sentiments toward Republicans — poor white people and young white people. Republicans now have a solid majority among whites of all ages, and they're making progress toward eliminating the income gradient as well.

David Leonhardt New NYT DC Bureau Chief

I was disappointed earlier when David Leonhardt wasn't tapped to fill one of the open New York Times op-ed slots, since his columns for the business section have been so good and so on point to the key issues facing the country that I thought they deserved that venue. But the news that he'll be is an exciting alternative.

In his columns and blog posts at least, he's been doing exactly what we see too little of in political journalism, namely an effort to figure out what's happening and why it matters. The Beltway convention of focusing exclusively on process, horse race speculation, and "he said, she said" has long struck me as not just annoying, but slightly more inexplicable than it appears at first glance. Newspaper coverage of foreign affairs and business stories isn't always perfect, but it does generally seem focused on the idea that people are reading a story because they want to know what's happening and what, if anything, is important about it. Leonhardt's columns have that exact spirit, looking at economic policy debates with an eye to trying to figure out who's right and what matters. If we see more of that infecting the general political coverage, then the country's best newspaper is going to get even better.

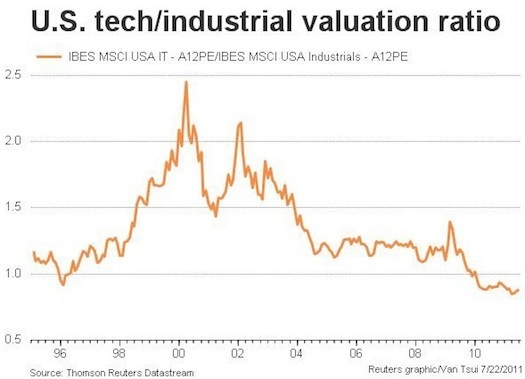

Idle Speculation On Tech/Industrial Valuations

How to explain the fact (via Kevin Drum) that industrial companies are now valued more aggressively than tech companies?

What this says is that markets are more pessimistic about the growth prospects for industrial firms than for high-tech ones. That actually seems quite reasonable to me. The thing about high-tech firms is that the stuff they make tends to be relatively cheap. A MacBook Air is a steal compared to a new car, and a used computer can be found for almost nothing. Google is free. If you imagine a world in which the bulk of growth is going to occur in large developing nations. So imagine hundreds of millions of Chinese, Indians, Brazilians, etc. achieving something resembling the lifestyle of lower-income people in today's rich countries. You're imagining a household acquiring a quantity of cars, washing machines, refrigerators, toasters, vacuum cleaners, etc. whose dollar value vastly exceeds the price of its total quantity of computers, smartphones, and software.

In America, for a long time now we've been in a kind of major appliance funk. People don't get richer and say, "Now I'm going to own seven toasters." People buy these kind of low-tech goods, but it's driven by population growth and depreciation. So the high-tech sector — new inventions — has been the high-growth sector. But in a world of catch-up growth you don't need to be "high-tech" to find new customers. There are lots of people around the world who don't own a blender.

How Are 'Weak' European Countries Supposed To Experience Growth?

In an interview with the New York Times about the Eurozone plan, Simon Johnson observes that "unless the troubled countries now show strong growth, there is still trouble ahead." Carmen Reinhardt sounds a cautionary note on this score, noting that "the process of deleveraging, as Vincent Reinhart and I have stressed, is a multiyear process that takes up the better part of a decade in the wake of severe financial crises."

I think that the history, though bleak, may even be creating false hope here. Ask yourself, under what circumstances would — say — Spain possibly start seeing strong growth? Given that Germany is already at full employment and the European Central Bank is already moving to tighten money, you need to imagine an increase in Spanish demand that doesn't cause an increase in German demand that prompts an offsetting ECB tightening. It could happen, I suppose, but it's difficult to spell a case out. Maybe the growing Chinese middle class will develop an intense, but incredibly specific, taste for Spanish wine and jamón serrano.

So you need reforms on the real side. Which is good. Obviously, real side factors are always important and countries prosper over the long run by improving their real economy. But austerity budgeting and high unemployment make it less likely, not more likely, that Spain is going to be able to improve its infrastructure and education system. Higher taxes and reduced services make it likely that Spain's highest-skill citizens will tend to leave the country at a higher rate and reduce the rate at which foreigners want to come to Spain. So you have regulatory policy reforms to increase efficiency. Obviously, I'm a believer in such things. But in general, it's a heavy lift politically. And it tends to get to be a heavier lift when you've already got mass unemployment. People become very resistant to any kind of efficiency enhancing reform that could cost them their job when there's double digit joblessness, and understandably so. What's more, these problems tend to be more of a "death by a thousand cuts" thing than a single problem you can easily fix. Of course if you have terrible pre-existing policies — think China in the mid-70s — you can get a giant real boost by letting farmers sell some surplus agricultural products at market. But is there some credible case that Spain and Portugal feature that kind of low-hanging fruit? How about the Irish Tiger? I'm not hearing about it.

This is a plan that only works with higher growth, but it has no path to create the growth or even create the conditions under which the growth is plausible.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers