Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2231

July 25, 2011

Safe Haven Oslo

One doesn't want to lean too heavily on human tragedies to make political points, but since a lot of our politics rightly concerns itself with how to minimize the occurrence of tragic events, it is necessary to try to see what can be learned. And to that end, it seems worth taking note of the fact that the weekend's bombing and massacre in Norway should remind us once again that "safe havens" in Pakistan and Afghanistan are neither necessary nor sufficient to undertake mass casualty attacks in the west. Indeed, the one thing you can say for sure about a wood-be killer located in Afghanistan is that he's not in a western country and thus has no ability to mount a major attack in the west. Any "safe haven" abroad is, by definition, too far away to open fire on a summer camp.

This also shows us — as did the plotting of the 9/11 attacks themselves by a cell in Hamburg — that generalized establishment of good governance is not sufficient to foil terrorist attacks. Germany and Norway are among the best-governed countries on earth. We would be lucky if the United States were to achieve the level of orderliness efficient administration that they have. It's simply not going to happen for Pakistan or Afghanistan in this lifetime. But at the same time, conventional law enforcement does have a pretty good track record of busting up plots. There's no perfect security, but these things are hard to get away with. But precisely the problem we don't have is the need to establish rough military control over large swathes of far-away foreign countries. This is both extremely difficult to pull off and largely unrelated to domestic security goals.

July 24, 2011

Who Commits Terrorist Attacks In Europe?

According to Europol's 2010 data (PDF) attacks by separatist/nationalist groups far outnumber attacks by Islamists.

I think this is important since the background condition of fairly widespread terrorism on the part of, say, Basque or Corsican terrorists helps us understand the correct context for a lot of Islamist violence, namely nationalism. If you look at Hamas, or the Taliban, or Pakistan-backed radicals in and around Kashmir it should be clear that ethnic nationalism is a major factor in all of these conflicts. It's true that because Islam is also the dominant religion in the areas in question that the groups have an Islamist ideological orientation that we should construe as sincere. But you also see violence associated with secular nationalism in Europe, with the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka. The long (and mercifully waning) conflict in Ireland has tended to break down along sectarian lines, but is normally (and correctly) seen as primarily national in character and not "about" theological disputes between Catholics, Anglicans, and Calvinists—i.e., it's not a conflict that gets resolved by making people less devoutly religious, and it's not mediated by compromising over liturgy.

New Research On Male Contraceptives

Pam Belluck rounds up the latest for the NYT:

The most studied approach in the United States uses testosterone and progestin hormones, which send the body signals to stop producing sperm. While effective and safe for most men, they have not worked for everyone, and questions about side effects remain.

So scientists are also testing other ways of interrupting sperm production, maturation or mobility.

One potential male birth control pill, gamendazole, derived from an anticancer drug, interrupts sperm maturation so "you're making nonfunctional sperm," said Gregory S. Kopf, associate vice chancellor for research administration at the University of Kansas Medical Center. The center has begun discussions with the Food and Drug Administration about the drug, already tested in rats and monkeys.

It seems to me that doesn't work for everyone and questions about side effect remain characterizes existing methods of contraception for women. That's one of the reasons why a variety of different methods have been developed. But isn't the real issue with male contraceptives the question of trust? After all, if something goes wrong, it's the woman who ends up pregnant and has a lot more on the line.

How To Move Americans Politics To The Left

Jeffrey Sachs unloads a truck full of righteous indignation on Barack Obama and the leaders of the Democratic Party. Some my find it cathartic. I find that while Sachs is a brilliant economist, his model of American politics seems flawed. In particular, the concluding thought that "America needs a third-party movement to break the hammerlock of the financial elites" is badly under-explained.

My counter-proposal, which is boring, goes like this. If you want to move US public policy to the left, what you have to do is to identify incumbent holders of political office and then defeat them on Election Day with alternative candidates who are more left-wing. I think this works pretty reliable. To my mind, the evidence is pretty clear that even the election of fairly conservative pushes policy outcomes to the left as long as the guy they're replacing was more conservative. And if your specific concern is that the Democratic Party isn't as left-wing as you'd like it to be, then what you need to do is identify incumbent holders of political office and then defeat them in primaries with alternative candidates who are more left-wing. It's noteworthy that even failed efforts to do this, such as Ned Lamont's 2006 run against Joe Lieberman and Bill Halter's 2010 run against Blanche Lincoln led to meaningful policy shifts simply by being credible. But left-wing critics of the Democrats often seem to me to be somewhat in denial about their poor record of success with these endeavors. "If we can't beat a Senator in Connecticut, let's take on an incumbent president who's substantially more liberal than Lieberman" isn't a logical program of action. The right lesson to learn from these Senate bids is that they're worth trying again if circumstances are right, but that even they may be too ambitious. You walk before you run. Maybe you win state legislative and House races before you win Senate elections. Research indicates that previous experience in elective office is one of the main predictors of candidate success, so perhaps it's only through a concentrated effort to increase progressive representation in state government that a pool of talented primary challenges can be generated. Or maybe there's a great Senate challenger right around the corner, and if so that would be well worth writing a column about.

This prescription is, I'm afraid, boring. And the solution proposed is, I'm afraid, hard work. But politics is hard work! The Republican Party has become very ideologically rigorous because the conservative movement now has a decades-long record of defeating incumbent officeholders at all levels in primaries, and then of having those winning primary candidates win a general election. This was and is an impressive achievement that required a lot of hard work over a long period of time.

Ideological Disagreement In Low Tax America

I think this chart from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities about how the United States is a low-tax country does a lot to explain the constant ideological angst that exists inside the progressive camp in this country. The issue is that the United States is a low tax country. In a high-tax country like Austria there's a relatively narrow range of plausible center-left views about the size and scope of the welfare state. It's always possible to mount a fairly radical critique of the Austrian status quo. But anyone thinking of themselves as a moderate sensible progressive is going to see a pretty narrow range of options available. "Maybe we should be more like Denmark." And maybe we should.

The United States is different. This is a country where saying that the state ought to be as large a role in the economy as it did in pre-crisis Ireland counts as a left-wing perspective rather than a right-wing one as it did in most countries. "We ought to be around the OECD average" is an even further left position. But a lot of people look at the Netherlands or even Sweden and see economically and socially dynamic societies with many admirable features. People holding all these views find themselves in the same political coalition. And since people holding all these views are arguing for the United States to imitate actually existing pleasant places (albeit small ones) it's possible for people holding all these views to deem themselves to be sensible, practical-minded, reformers and not at all pie in the sky radicals. But "we should be like Ireland," "we should be like the Netherlands," and "we should be like Sweden" are actually dramatically different policy proposals. And certainly in the Netherlands "we should be like Ireland" and "we should be like Sweden" would be correctly understood as very different agendas, whose adherents would find themselves on opposite sides of the political debate. Here in the United States, a very right-leaning status quo combined with a two party political system means that people with sharply divergent ideas are all "on the same team."

A related point, very relevant to the ongoing debt ceiling negotiations, is that there's substantial ambiguity around what the status quo even means going forward. The United States has the option of persisting with some very much like Medicare and Medicaid in their current forms, but doing so would require substantial changes in the level of taxation. Conversely, we have the option of persisting with a level of taxation similar to what we've had historically but doing so would require fundamental changes in government health care and retirement programs. Consequently, people proposing fairly dramatic changes on both the tax and health can can plausibly see themselves as defending the status quo.

My Favorite Ridiculous Thing Written By A Conservative Over This Past Weekend

Erick Erickson nails it:

Secular leftists and Islamists are both of this world. Christians may be traveling through, but we are most definitely not of the world. In fact, Christ commands us to throw off our ties to this world. But the things of this world love this world and hate the things of God. That's why secular leftism can embrace both activist homosexuals and activist muslims when the latter would, when true to their faith, be happy to kill the former.

I wonder how Jews fit into this framework?

Who Teaches The Teachers

Here's an excellent long take from Sharon Otterman about the vexed issue of training teachers. The point where "reformers" and skeptics are probably most in agreement is on the desirability of improving training, and since America already has a lot of teachers it already has a lot of education schools and training programs. But very little is known about best practices in this regard and the actual quality of the instruction involved seems to be pretty poor on average. There's scant evidence that the master's degrees many teachers are encouraged to obtain actually help anyone, and on average education majors show less learning gains while in college than people studying any other field.

None of this is new to anyone, but what exactly to do about it is contentious. Otterman gives a great overview of some of the practitioners making efforts to improve things in a first-order way with new programs. On a more structural note, Edward Crowe did a paper for CAP arguing that we ought to at least try to measure which schools are graduating good teachers.

July 23, 2011

Amtrak's Expensive Trains

That the US invests less in passenger rail than Europe or Asia is obvious. Less well known is that with its smaller budget, Amtrak also buys more expensive stuff:

Unfortunately, Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood's recent announcement of a $562.9 million loan to Amtrak to buy new locomotives for the Northeast Corridor suggests that they will not be doing more with less. The money will go to buy 70 electric locomotives, which, as Alon Levy at Pedestrian Observations explains, are far more expensive than comparable European and Japanese models, and will lock us into outdated technology for decades to come.

Europe and Asia have realized the benefits of lighter and more nimble trains – cost, speed, and energy consumption among them – but Amtrak's planned purchase is further proof that the U.S. is not quite there yet. One easy cost-saving move would be to wait two years for Positive Train Control, an anti-crash safety technology, to be fully installed along the Northeast Corridor. By 2015, Amtrak will no longer have to comply with the Federal Railroad Administration's requirement that trains be able to withstand crashes with enormous freight trains. Free to buy lighter off-the-shelf foreign designs, Amtrak could then save 35-50 percent off the cost of the locomotives, as Alon notes.

An even more radical modernizing and cost-cutting measure (at least in the long run) would be to transition the Northeast Corridor Regional fleet from locomotive-hauled trains to electrical multiple units, or EMUs, in line with best practices in Europe and Asia. EMUs are, like subways in the US, individually-powered carriages, and standard models can be as cheap as the inflated price that Amtrak pays for its unpowered passenger railcars. The locomotive purchase locks Amtrak into buying more of these unpowered carriages in the future, making Amtrak's decision to go with locomotives all the more important.

I don't particularly want Amtrak to do more with less. I'd like it to do much more with more. But either way, it would be better to act cost-effectively. A stingy, yet high-cost, rail system is bad news.

Banks and Corporate Governance

Bethany McLean discusses the corporate governance aspects of the Dodd-Frank law:

One part of the problem is that in these days of publicly-traded banks and brokerages, the interest of the bankers and the interests of the banks' stockholders aren't always the same. If an executive can pocket tens of millions in cash compensation in the short term, he will fret a bit less about the future of his firm, or even the money he might still have tied up in it. Dodd-Frank contains some provisions that attempt to better align compensation with a bank's long- term performance, such as the ability to "clawback" executive compensation that's based on improper financial statements. These reforms may not work, but they're well worth trying.

The more I think about this, the more I think it may be doomed. After all, who's going to be good at gaming a compensation scheme if not a bank executive? Bankers are particularly tricky in this regard not only because they have specialized skills in the field of financial gamesmanship, but because I think they have less in the way of intrinsic motivation that most high-achieving professionals. An architect wants to make money, but he also wants to make buildings he likes. A basketball player wants money, but he also wants rings and acclaim. A pundit wants to earn a living, but he also wants influence. But banking isn't something you do that you also get paid for, it's just getting paid to make money.

Contrast this kind of complicate scheme with the alternative idea of a crude rule mandating that large banks be partnerships or otherwise owned by a small number of people rather than publicly traded firms owned by retail investors. After all, "these days of publicly-traded banks and brokerages" is a pretty recent phenomenon. Was there some specific social or economic problem with the old paradigm that the rise of publicly traded banks solved? Many aspects of bank deregulation did, in fact, solve actual problems. Having banks be able to operate branches in multiple states creates actual convenience for customers in a clear way. But what was the problem with a lack of publicly traded investment banks?

Jump Starting And The Fiscal/Monetary Interplay

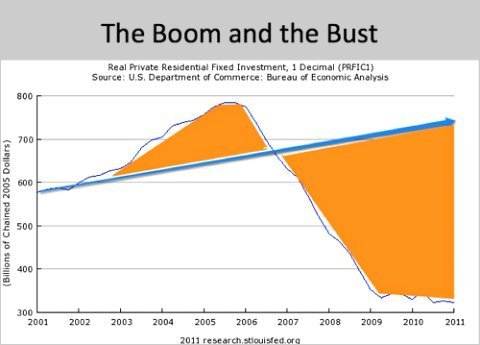

Paul Krugman notes that the prolonged housing slump seems to suggest that a relatively modest fiscal boost could push us to a higher employment equilibrium:

Suppose that Obama announces that we face a clear and present danger from Ruritania, and that to meet that threat we need immediate investment in roads and rail (to move troops, of course). The economy surges on the emergency spending — and newly employed men and women at last get to move out of their relatives' basements. Home construction surges. Then Obama apologizes, says that his advisers have learned that there is no such country as Ruritania, and cancels the program. But we still have the new roads and rail links; plus, the surge in housing demand is now self-sustaining, and the economy remains strong.

And of course we could do this even without the pretend invasion. But there is (as ever) a monetary angle. As Karl Smith puts it before increased demand leads to increased supply of homes, it needs to lead to higher rents. Among other things, you can't build a home instantaneously. That has implications for the proposed anti-Ruritanian fiscal boost. In particular, if the Federal Reserve is happy with the current inflation rate that means it's going to need to tighten money during the "higher rents" phase and short-circuit the fiscal boost. Which is just to say that any time fiscal policy works, it's going to work in part by increasing the price level which means it will only work if it's tolerated by the central bank.

How exactly this goes together depends in part on your model of what's happening at the Federal Reserve. One way of looking at it is that if the Fed were willing to accept a higher inflation rate, they'd be doing QE3 right now. So the fact that they're not doing QE3 shows that they would tighten money to offset any boost from fiscal policy. Hence, even though fiscal policy could work, it wouldn't. Another view, however, is that the Fed isn't doing QE3 primarily because of political worries around QE3 itself. If the US Congress and President Obama were to initiate a fiscal stimulus that they claim responsibility for, the Fed would be happy to stand pat and let the price level rise, issuing a statement about the continued existence of excess capacity and well-anchored expectations. This is a scenario considered by Scott Sumner:

This suggests the Fed's previous actions have given her a "loose" reputation. She's willing to be easy, but not that easy. Of course you and I know that monetary policy has been very tight. But what matters in questions of virtue are perceptions. And there are few areas of life more permeated by Victorian morality that monetary policy.

If this is the problem, then fiscal stimulus might just work. The Fed cares about the perceived stance of policy. It wants more NGDP, but isn't willing to put out.

All things considered, this highlights the extent to which non-transparency and lack of accountability at the Fed has itself become a problem. A medium-sized fiscal boost might solve all our problems by sparking a self-sustained recovery, or it might be a total waste of money and which it is depends on one's view of the murky internal politics of the central bank.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers