Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2235

July 21, 2011

'Stealing' Involves Depriving Someone Of The Use Of Something To Which He Or She Is Legitimately Entitled

This piece from Kevin Webb on Aaron Swartz, digital media, scholarship, and free inquiry is just great. So great that I won't quote or attempt to summarize it beyond echoing Webb's observation that Tim Berners-Lee pioneered the World Wide Web specifically in order to facilitate the sharing of scholarly information.

I will, however, quote U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz who has some nutty ideas about what is and isn't stealing:

"Stealing is stealing, whether you use a computer command or a crowbar and whether you take documents, data, or dollars," US Attorney Carmen M. Ortiz said in a statement. "It is equally harmful to the victim, whether you sell what you have stolen or give it away."

This is absurd. I wrote a book once, titled Heads In The Sand. I both own physical copies of the book and own the copyright to the content of the book. It is obviously not equally harmful to me if you break into my house and steal my physical copy of the book than if you were to somehow go to the library and make a photocopy of the book. The difference, not at all subtle, is that when you steal something of mine (be it my book, my iPad, my shoes, my money, my immersion blender or whatever), I don't have it anymore. If you copy something that you're not allowed to copy without my permission, that's a very different issue. Perhaps you deprive me of income I would have had if you hadn't done that, or perhaps you don't deprive me of anything. As I've said before, I sometimes beg online for someone to send me a copy of an academic article that I can't get free access to. It's never the case that my fallback option in this situation is to purchase an extremely expensive academic journal subscription. Nobody is harmed when this sort of copying occurs, and even in the cases where there is a harm the nature of the harm is quite different from the harm incurred in actual cases of theft.

I'm not really sure why the people charged with enforcing copyright law are obsessed with obscuring this fact. The laws against stealing are hardly the only laws on the books. There is a perfectly sound public policy rationale for requiring cars to have license plates, but nobody would say "stealing is stealing whether you take someone's car or just drive your own car without license plates." The regulations against copying are supposed to "promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries." That's a good reason to have a set of rules, but it's a reason that has nothing to do with "stealing." The question is whether the rules we currently have are actually good ways to achieve this goal.

More Savings Commitment Devices Needed

Felix Salmon has a great summary of the Eli Beracha / Ken Johnson paper showing (PDF) that buying a home is rarely a good investment decisions. But to summarize even more briefly, their key point is that you either rent a house or else you rent money from a bank to buy a house with, so you can't avoid "renting." They show that the vast majority of the time, you'd do better to rent a house and invest the extra money you come out ahead. But as Salmon explains, though true, this sort of misses the point:

To put it another way, a mortgage is a commitment device. You're forced to spend all that money on your mortgage each month; if on the other hand you rent, you're very likely to simply spend the excess, rather than save it. The e21 people reckon that only "myopic households" would not otherwise save the difference, but that's just not realistic. People stretch to make their mortgage payments, and without the mortgage there there's no need to stretch so hard, and you can enjoy your life more instead — go out, go on holidays, buy nicer clothes or extra iPads.

But the exercise in the paper is well worth running all the same. People get real value out of consumption, and so when you buy rather than rent you're essentially denying yourself all that extra fun and pleasure. And if you both rent and deny yourself the extra fun and pleasure, then you'll end up with more money than the buyer.

In other words, people who save via investing in their own home are paying a penalty vis-a-vis people disciplined enough to save an equal amount of money through other means. Which makes sense. Many of us are mildly present-biased in our decision-making, and thus benefit over the long term from bearing mild costs to overcome that myopia. But from a policy perspective, the interesting question this raises is what more can we do to provide people with other kinds of convenient commitment devices? I used to hear a lot of discussion about flipping the default on 401(k) plans so that you would start a job with your contributions set at a high level, and then you'd need to take active steps to save less money. That seems to make sense.

Breakfast Links: July 21, 2011

— John Siracusa's epic review of Lion.

— Apple has $75 billion in cash and liquid securities.

— DARPA unveils the Nexus 7.

— Larry Summers on infrastructure and stimulus.

— Wall Street making backup plans in case of default.

— Jonathan Turley makes the case for polygamists' rights.

— Americans are drinking less and doing fewer drugs.

— Europe's perfect financial storm.

— French and German governments claim to have reached a secret deal to save the Euro.

— Platinum coin mania spreads.

— Happy birthday to the Dodd-Frank financial regulation bill!

July 20, 2011

Organic Agriculture Needs More Government, Fewer Pesticides

By Matthew Cameron

Blogging at Scientific American, Christie Wilcox offers an informative smackdown of several common misconceptions about organic agriculture. In particular, she takes on the myth that organic foods are produced without the use of any chemicals:

[It] turns out that there are over 20 chemicals commonly used in the growing and processing of organic crops that are approved by the US Organic Standards. And, shockingly, the actual volume usage of pesticides on organic farms is not recorded by the government. Why the government isn't keeping watch on organic pesticide and fungicide use is a damn good question, especially considering that many organic pesticides that are also used by conventional farmers are used more intensively than synthetic ones due to their lower levels of effectiveness. According to the National Center for Food and Agricultural Policy, the top two organic fungicides, copper and sulfur, were used at a rate of 4 and 34 pounds per acre in 1971. In contrast, the synthetic fungicides only required a rate of 1.6 lbs per acre, less than half the amount of the organic alternatives. [...]

Just last year, nearly half of the pesticides that are currently approved for use by organic farmers in Europe failed to pass the European Union's safety evaluation that is required by law. Among the chemicals failing the test was rotenone, as it had yet to be banned in Europe. Furthermore, just over 1% of organic foodstuffs produced in 2007 and tested by the European Food Safety Authority were found to contain pesticide levels above the legal maximum levels – and these are of pesticides that are not organic.

These are significant shortcomings, but they are not reasons for abandoning the concept of organic agriculture altogether. Rather, they reinforce the point that good governance is key to setting and enforcing agricultural standards that protect the environment. If the USDA and the EPA are aware that certain organic producers are using large enough quantities of nonsynthetic pesticides to negatively impact the environment, then the solution should involve setting more stringent regulations on the types and quantities of pesticides that may be used in organic production. Similarly, if the European Food Safety Authority is finding synthetic pesticides in organic food products, then it should implement more robust enforcement mechanisms to ensure that producers aren't skirting the rules.

The Government Spends A Lot of Money Because It Pays High Prices For Health Care Services

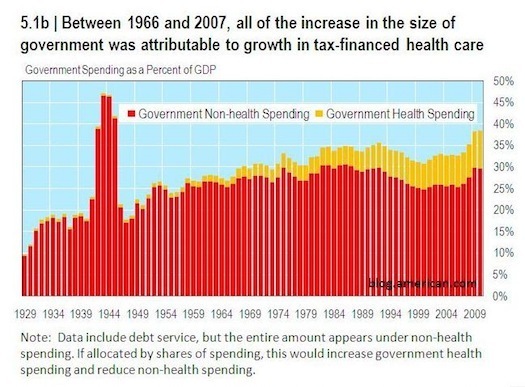

I don't particularly agree with his interpretation, but I think Christopher J. Conover does American conservatism a favor with his article about how health care is the health of the state. He's making the point that growth in government spending is overwhelmingly not the consequence of grasping liberals coming up with evermore things for the government to do. Instead, the government has for a long time shouldered responsibility for health care finance, and health care is very expensive.

Something I would note about this is that the basic principle here is much less controversial than conservatives sometimes pretend to believe. The existence of "private" health insurance in the United States is largely an artifact of elements of the submerged state. We provide a large tax subsidy for employer-provided health insurance that makes it cost effective for firms to offer group health insurance plans to their workers. We also prohibit employers from engaging in risk-screening when they put their group health insurance pools together. And we have continuity of coverage regulations that ensure that a person can get a job, then get insurance, then develop an illness, and then get a new job and get new insurance with the new job without losing her coverage. Absent those "big government" interventions into the marketplace, many fewer people would have health insurance and the political demand for formal government provision of insurance would be higher than it currently is.

State of the art progressive thinking on this subject features ideas like all-payer rate setting and IPAB that are supposed to wring waste out of the system. State of the art conservative thinking, as embraced in the House GOP budget, is to just refuse to pay what medical treatments cost. Except because this is totally untenable, their idea is to promise today that we'll refuse to pay what treatments cost in the future. But will we? I don't see any reason to think we actually will. Efforts to change the cost structure might fail, but you could at least imagine them succeeding. Imagining some future scenario in which elderly people don't get health care and everyone stands around saying "well, Paul Ryan said it would be smart to do it this way 20 years ago" doesn't make any moral or political sense to me. Sometimes you've just got to pay the taxes.

National Park Service Proposes Removing Automobile Infrastructure From The National Mall, Citing Historic Preservation

That blockbuster story comes via Dave Alpert:

Line said the Mall is covered by the same laws as other national parks such as the Grand Canyon, Yellowstone, and Yosemite. Putting a bike station on the Mall would violate the National Historic Preservation Act because a station would be seen as going against the historical purpose of the Mall and its monuments.

"The National Park Service reflects an American heritage and what a particular park means to American citizens, not (necessarily) at (the) convenience of select individuals," Line said.

Oh, wait, they're talking about a Capital Bikeshare station not about the highway ramps and automobile-only asphalt. That stuff's there because of American heritage rather than the convenience of select car owning individuals.

Interactive Map Highlights Impact On State Budgets If Debt Ceiling Isn't Raised On Time

Very cool interactive graphic that really brings home how cataclysmic a failure to raise the debt ceiling will be for state and local governmnets.

Gang Of Six Proposal Raises Much More Revenue Than Deal John Boehner Already Rejected

Important nuance from Bob Greenstein at the CBPP who notes that the $1 trillion in new revenue from the Gang of Six plan isn't the same as the $1 trillion in new revenue from the "grand bargain" talks between President Obama and Speaker Boehner. In particular, the Gang of Six plan assumes the expiration of the high-end Bush tax cuts and then adds $1 trillion in revenue. The deal Boehner rejected merely assumed $1 trillion in revenue over a baseline that assumes all Bush tax cuts are made permanent. That furthers my impression that this proposal will be DOA in the House once House members understand it.

However, it's also worth emphasizing an additional point here. The quantity of revenue that Obama is trying to get the GOP to agree to provide is less than the amount of revenue he could get simply by vetoing any extension of any aspect of the Bush tax cuts. Obama's not doing that because he wants to fulfill his campaign pledge to permanently extend much of Bush's tax package, and he's not doing it because he wants to get Republicans to vote for tax increases rather than do it unilaterally. But if the goal here is just to obtain revenue, the best way to do it is with the veto pen rather than the bargaining framework.

What Fills The Gap As Wages Fall?

On Monday, I noted the falling labor share of GDP. This of course raises the question of what's rising. "Profits" are of course one answer, but who actually gets the money? One window into this (via Jon Witt) is provided by the Congressional Budget Office's classic 2008 letter to Senator Max Baucus "Historical Effective Tax Rates, 1979 to 2005: Supplement with Additional Data on Sources of Income and High-Income Households."

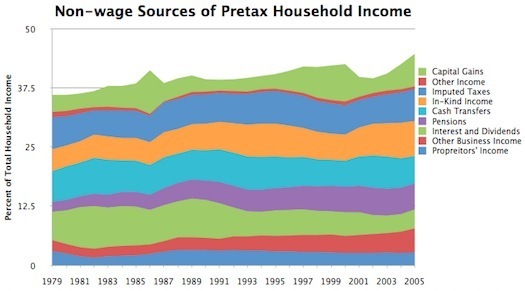

Specifically, in order to calculate effective tax rates the CBO needs to look into what kind of income people are earning. Mostly, it's wages. But wages have been falling as a share of the overall household income pie and this area chart from Matt Cameron helps us see what's been growing:

In a somewhat surprising way, the decline of wages hasn't led to a big increase in the share earned by capital. It's true that capital gains rose from 3.6 percent of national income in 1979 to 6.9 percent in 2005, but this was largely offset by interest and dividends shrinking from 6 percent to 4 percent. On net, that's capital (broadly defined) going from 9.6 to 10.9—not nothing, but small compared to the overall shrinkage. Meanwhile, "proprietor's income"—the money people earn from operating their own businesses—has slightly declined.

Bigger increases are in things like pensions (2.1 percent to 5.5 percent) and in-kind benefits (4.6 percent to 7.4 percent). The pensions thing is obviously an artifact of population aging, so it's easy to understand. The rise in in-kind benefits presumably reflects the increase in health care spending, so we also have a good handle on that. But the more than doubling of "other business income" from 2.3 percent of total household income to 5.1 percent of total household income is a little harder to understand. This is defined by the CBO as "[p]artnership income, income from S corporations, and

positive rental income."

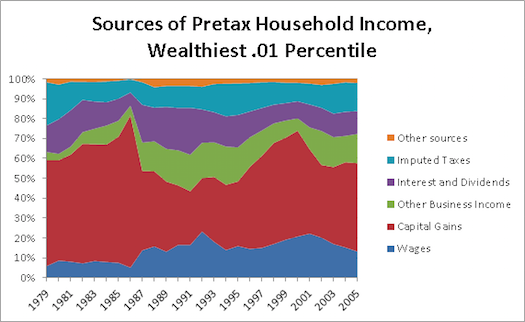

Clearly the background here is the explosion in high-end inequality in the United States during this period. But it's interesting to note that even though we've both had an explosion in high-end inequality and a structural decline of wage income, it's not the case that these two trends represent a structural shift in earnings away from workers and toward interest, dividends, and capital gains. Indeed, if you look specifically at the top 0.01 percent you see that over time they've come to rely less and less on capital gains and dividends:

The big action here is a steady increase in the super-rich's reliance on wages and an explosion of the dread "other business income." Now of course the overall incomes of the super-rich were growing strongly throughout this period, so it's not like they didn't see capital gains income grow. But the point is that even as the rich have gotten richer, they've become less dependent on capital income.

Academic Work Should Be Distributed For Free

Tim Lee has an item on the Aaron Swartz arrest that strikes me as a bit wrongheadedly concern trolly, fretting that "the more lasting cost of Aaron's actions will likely be to the reputation of the open access movement."

This I doubt. Most likely, the lasting benefit of his actions will be to elevate the salience of the underlying issue on which Lee, Swartz, and I are all in agreement. And here's the issue. Right now in academic publishing, what you have is basically a lot of donor- and government-financed nonprofit organizations taking outputs with near-zero distribution costs (electronic journal archives) and selling them to each other. For any one institution, this kind of makes sense. A publisher doesn't want to give up his fees, which are valuable in meeting the costs of producing scholarship. But on net, it's a mix of pointless and pernicious. Sale of access to journals helps finance scholarship, but it also raises the cost of scholarship. If everything was distributed for free, the whole exact same enterprise could be undertaken with no net financial loss. But there would be huge potential gains. A precocious 17 year-old could have free access to scholarship. So could a researcher living and working in a poor country. Or even an earnest political reporter who's working on an issue and curious about what political science has to say about it. When I, personally, come across an article I'd like to read but can't get free access to, my standard practice is to tweet about it and then someone affiliated with a university sends it to me. That's good for me and, I think, good for the world. But there's no reason curious people should need to amass thousands of twitter followers before they're able to gain access to information that's been produced by non-profit institutions that are supposed to be serving the public interest.

Both governments and private donors expend a good deal of funds on subsidizing the production of scholarly knowledge. That's an excellent idea. Increasing the overall stock of human knowledge is important. But for most of the same reasons that producing scholarship is important, making it available is also important. Open access is important, and I'm glad to see people fighting for it.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers