Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2242

July 14, 2011

Debt Ceiling: Institutional Design By Accident

It's clear at this point that the function of the statutory debt ceiling is to allow an opposition-party congress to try to extract some concessions from the White House. So you might think that was the purpose of the thing. But you'd be wrong. As Sarah Binder explains the original idea was simply to free congress of the responsible to authorize each individual issuance of debt:

Judging from the NY Times coverage of the 1917 episode, legislators paid little attention to the implications of mandating a ceiling. They focused instead on Treasury Secretary McAdoo's request for a higher borrowing limit so as to fund an expensive war effort. The ceiling was created to empower, not rein in, Treasury (prompting a failed effort to create a congressional committee to oversee Treasury's actions). Similarly, the creation of the aggregate ceiling in 1939 reflected congressional deference to Treasury, granting the department flexibility in refinancing short term notes with longer term bonds. As the Senate floor debate makes clear, senators viewed the move as removing a partition in the law that hampered Treasury's ability to manage the debt.

This is basically just one of those things that turns out to happen when your country has an unusually long period of continuous government. An institution that was set up at one time for one reason morphs around into something else. Unfortunately, the current practice represents a major threat to the economic health of the country, one that won't go away even if we resolve the current standoff.

Short-term Politics vs. Long-term Growth: Agricultural Regulation Edition

By Matthew Cameron

The primary policy lesson of yesterday's USAID seminar about sustainable agriculture was simple enough: Good governance is crucial for setting and enforcing standards that promote responsible food production. The politics of achieving this objective, however, are rather tricky.

This is because politicians and citizens typically view such regulatory decisions as involving trade-offs between environmental protection and economic growth. It's tough for the environment to win that battle, especially in developing countries where people desperately want higher living standards. In fact, even in advanced economies such as the U.S., politicians often use a reductionist approach to conclude that anyone who is pro-environment is anti-growth (the ongoing controversy surrounding commerce secretary nominee John Bryson is a perfect example).

In reality, decisions regarding agricultural regulations revolve around the even more complicated axis of short-term political benefits versus long-term economic growth. Consider the situation faced by a Communist Party politician in a coastal province of China. He must decide whether to set and enforce catch limits on various types of fish that live in his territory's waters. Knowing that his chances at career advancement depend upon the economic performance of his province as well as his popularity among the local population, the politician is likely to enact policies that will maximize his constituents' incomes. Since he also knows that fish can fetch a high price on the global market because of rising demand, he will be loathe to mandate that the fishermen of his province limit their catch to protect species' population levels. This is particularly true since he knows that if he does so, a rival politician in a neighboring province is likely to take advantage of the situation by encouraging his citizens to fill in the supply gap by fishing even more.

Now, letting his citizens fish without limit may be great for the politician's career, but it's terrible for the long-term growth prospects of his province. Eventually, overfishing or ecosystem damage will cause the local fishery to collapse. With an appropriate time horizon, there's no real trade-off between maximizing fish-related income and responsible management of the fishery.

Spending, Growth, And The White House Political Strategy

I don't agree with President Obama's decision to prioritize securing a long-term budget deficit reduction package in 2011. But I do think some of the criticism of this idea that I'm seeing somewhat misstates the situation. In particular, I hear people baffled as to why the president would pursue growth-reducing spending cuts that would damage his own re-election bid.

It's generally wise to assume that the White House isn't blind to that obvious potential political problem. Part of what they're thinking is that a 2011 agreement to long-term spending cuts is the best way to avoid the need to reduce spending during the election season. How's that? Well, it's because the fiscal consolidation plans being discussed are for trillions of dollars worth of cuts over a 10-year horizon. Since you've got that horizon, it's not strictly necessary for any of them to come between September 2011 and November 2012. On the contrary, in principle spending could go up in the short-term consistent with any long-term cuts. By contrast, what happens if the White House winds up getting a "clean" debt ceiling increase is that we then head into the September lapse in appropriations. It'll be a replay of the "government shutdown" fight in which the GOP goal has to be short-term cuts. And the White House isn't going to get away without giving something up in that fight. In other words, clean debt ceiling increase = guarantee of fiscal anti-stimulus, whereas a 10-year spending cut plan leaves open room to avoid that.

There are a lot of assumptions going into that analysis, and I'm not sure it's right. But this is the thinking and it's not crazy. The administration understands the way short-term fiscal policy relates to their 2012 campaign.

U.S.-China Trade Rebalancing

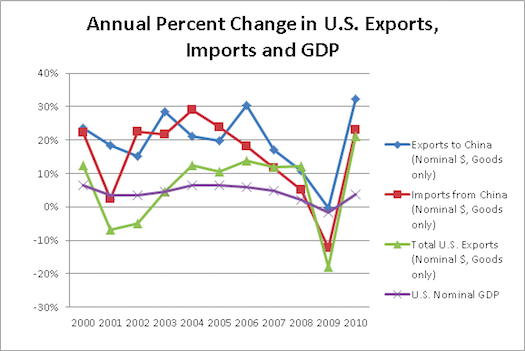

The bilateral U.S.-China trade deficit in goods is obviously quite large. At the same time, China's export engine has powered it to an astounding series of high-growth years. These two facts, however, create a discourse that sometimes obscures the underlying trend. The value of U.S.-made goods being exported to China is increasing very rapidly. More rapidly than the value of China-made goods that we're importing. More rapidly than overall US goods exports. And much more rapidly than overall US GDP:

An interesting analysis from the New York Fed says that Chinese currency revaluation would further increase the growth rate of American exports to China. The authors say that the net impact on the bilateral deficit would, however, be small. That's because "made in China" stuff includes lots of foreign inputs, and those inputs would get cheaper under revaluation. Consequently, the net price of Chinese-made goods would stay similar and U.S. exports are growing from a relatively small base, so the gap would stay large. Still, exporting to China has been a very high-growth segment for the American economy and revaluation could boost it into even higher gear.

No Sign Of 'Isolationism' In The United States

You can tell how primed Washington, DC is for global military domination because pretty much any sign of anyone anywhere resisting any form of military involvement anywhere in the world is characterized as a rise in "isolationism." But as Michael Cohen argues nothing of the sort is happening:

No major political figure and certainly no presidential aspirant is calling for the U.S. to end its membership NATO or other international institutions; none are suggesting that the U.S. bring troops home from East Asia, where more than 60,000 US troops are stationed, predominately in South Korea and Japan; and few are talking about closing down overseas U.S. military bases. Even in a time of economic uncertainty, calls for greater protectionism or an end to trade agreements are few and far between. If anything, expanding trade seems to be one area where Congressional Republicans and the White House are on the same page.

When it comes to the defense budget, few political leaders are pushing for military spending to be cut. Republicans balked at Obama's call for $400 billion in Pentagon savings over ten years, accusing him of insufficient fortitude in maintaining American defenses. Just last week, the House, with only 12 dissenting GOP voices, passed a defense spending bill that would increase the Pentagon budget by $17 billion. There seem to be more warnings today about incipient isolationism than actual examples.

Imagine a presidential candidate who wanted to maintain America's defense alliances with Japan, South Korea, and NATO and maintain a conventional military capability sufficient to participate meaningfully in the defense of those countries against foreign attack. Say this guy separately wanted enough nuclear weapons to credibly deter a Russian nuclear strike. But nothing beyond that. No AFRICOM, no CIA agents running around Somalia, no talk of a permanent presence in Iraq, no actual need for ground troops in Korea, etc. It would be considered an outlandishly leftwing and "isolationist" stance. And yet there'd be nothing actually isolationist about it.

Bernanke Warns That Spending Cuts Could Derail Growth

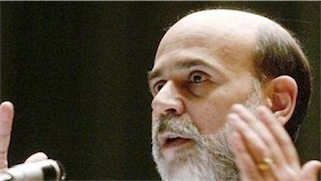

I was pondering Scott Sumner's argument yesterday that a true inflation-targeting regime from the Federal Reserve would imply extremely small fiscal multipliers. But it's difficult to get around the fact that this cuts against the stated views of the Fed's top official as well as all the staff economists I've ever heard from:

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke warned Congress on Thursday that overzealous cuts to government spending could derail an already fragile recovery and said a U.S. debt default could wreak financial havoc.

"I only ask … as Congress looks at the timing and composition of its changes to the budget, that it does take into account that in the very near term the recovery is still rather fragile, and that sharp and excessive cuts in the very short term would be potentially damaging to that recovery," Bernanke told members of the Senate Banking Committee.

There are a lot of ways you can reconcile Bernanke's view with Sumner's, including by just saying that the Fed isn't doing inflation targeting. But it sure would be nice to know what the Fed's own theory is. The ambiguity around this is one of several reasons that I think it would be desirable for the Fed to have a clearer and less ambiguous mandate.

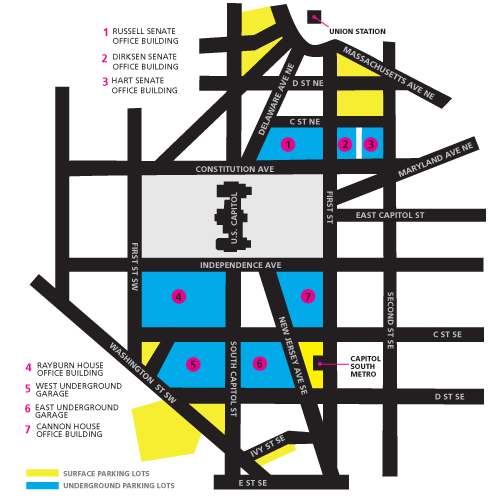

Capitol Parking Lots Are Worth $350 Million

Lydia DePillis writes about Congress' horde of surface parking lots:

At the same time, a tea-partying Congress is pushing the General Services Administration to sell off underused real estate in hopes of streamlining the federal portfolio and generating some extra cash. The Capitol grounds don't fall under the General Services Administration's authority; Congress tends to exempt itself from policies it pushes on the executive branch. But how much would they net the government if they were sold off? Adding up each of the lots, using their current D.C. assessed values, yields a ballpark estimate: About $350 million.

There are two ways of looking at it. One is that as an austerity measure, unlike cutbacks in federal spending, selling this land would reduce debt in a way that boosts the economy since some employment would be created developing the land. Another way is that if you sell the land and "cash out" the revenue in the form of higher pay to congressional staff, the overall impact on the federal balance sheet is nil, but the city benefits.

Brookland NIMBYs Killing The Environment

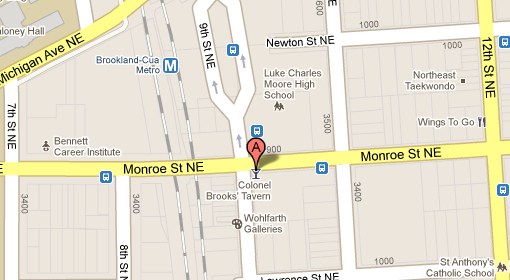

Here's a map highlighting the location of 901 Monroe Street NE in Washington, DC:

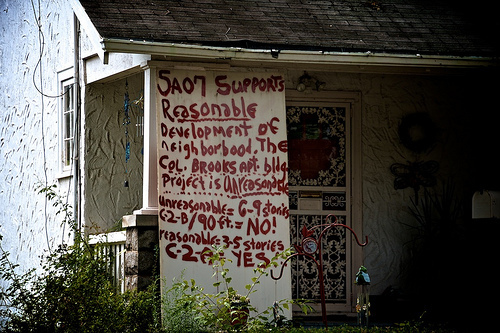

As you can see, it's right by a Metro station. Many people, myself included, would like to see America consume less gasoline. One good way to achieve this is for more people to ride mass transit. Unfortunately, building heavy rail mass transit systems is quite expensive. Nonetheless, it's often worthwhile. But once you invest the vast sums of money needed to build one, the general idea is that you want residences and commercial space to be located near the stations. A reasonable question to ask is, "Should we have as much stuff near stations as the market provides, or should we provide special subsidies to encourage station-adjacent building?" What we do instead in this country is place severe regulatory restrictions on how many people are allowed to live near Metro, and then neighborhood busybodies complain that the restrictions aren't sufficiently severe:

This kind of thing — a floor or two lopped off here or there — may not seem like a big deal. But there's some real wisdom in the idea of thinking globally and acting locally. The global consequences of this floor-lopping are several fold. One, it means more car driving in the DC area. Two, it means that investing in rail transportation looks like a worse investment for cities to make, so fewer places will do it in the future. Three, it means that there will be housing shortages near Metro stations, so transit investments will be associated in people's minds with "gentrification" and people being forced out of their homes rather than with overall amelioration of conditions. On its own, as a single action, it's not that big of a deal. But repeated over and over again on every desirable patch of urban land in America, the consequences are large and pernicious.

Silicon Valley: Not Enough Of A Good Thing

The United States of America is a gigantic country in a way that I think sometimes confuses people. To me, that's what's going on when Thomas Friedman suggests that the low level of employment at a handful of high-tech firms is important to understanding macro-scale trends in the American economy:

Look at the news these days from the most dynamic sector of the U.S. economy — Silicon Valley. Facebook is now valued near $100 billion, Twitter at $8 billion, Groupon at $30 billion, Zynga at $20 billion and LinkedIn at $8 billion. These are the fastest-growing Internet/social networking companies in the world, and here's what's scary: You could easily fit all their employees together into the 20,000 seats in Madison Square Garden, and still have room for grandma. They just don't employ a lot of people, relative to their valuations, and while they're all hiring today, they are largely looking for talented engineers.

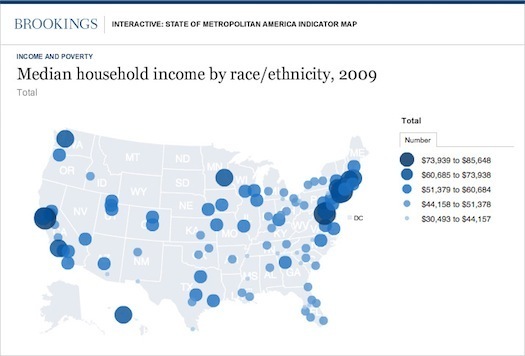

This is definitely true. But it's a little misleading to think that it explains poor conditions nationwide. Courtesy of the Brookings Metropolitan Project's handy data map, we can see that the San Jose-Sunnyvale MSA has a median household income of $85,000. That's number two in the country. And the San Francisco-Oakland MSA comes in at number four with a median household income of $74,000. The national figure was $55,000. And those are median figures, not means. It's not just that Mark Zuckerberg is really rich. Even though the main high tech firms have relatively few employees, they still serve as the tentpoles for what is, overall, a region that's much more prosperous than the rest of the United States. If the Bay Area were a country, it would have about the population of Austria or Sweden and we'd be hearing constantly about its miraculous prosperity.

It's also not just that the median resident of the Bay Area is a computer programmer. The presence of successful high-tech firms in the area creates spillover economic for everyone from accountants to chefs to bus drivers, construction workers, nurses, journalists and all the other varied stripes in the rainbow of a modern service economy.

The right questions to be asking aren't "why does Silicon Valley create so few jobs;" it's "why doesn't everyone move to the Bay Area" (the rent is too damn high) or "how come there's only one high-tech cluster." After all, if industrial age capitalism had just created the prosperity of the Detroit area in its heyday, we'd look on it as a huge bust. But we had lots of industrial production clusters, of which the Detroit automobile industry was just the most famous.

Aux Armes Citoyens

Haven't actually seen this movie, but fun clips of soldiers running amok set to "La Marseillaise" seems appropriate for Bastille Day:

A couple of hundred years later, I think we can say that revolutionary violence is not the best way to vindicate the kind of republican and liberal ideas that inspired the revolution, but this was not clear at the time. All honor to those who later developed the concepts of non-violent resistance. I learned about the revolution from Patrice Higonnet whose Goodness beyond Virtue: Jacobins during the French Revolution is a very interesting book, but perhaps not a great general introduction.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers