Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2240

July 16, 2011

The Trouble With Grand Bargaineering

Reihan Salam rights about some of the social origins of political polarization in the fact that different kinds of people live in different kinds of places. To this I would add the baseline fact that extreme non-polarization in the 20th century was an artifact of Jim Crow. Members of congress' views on economic policy didn't correlate strongly with their views on highly salient race-related issues. And to that I would add Alan Abramowitz' point that the modern electorate is much better educated and ideologically aware than was the electorate of the Gilded Age era of polarization.

All of this makes it quite difficult to achieve a "grand bargain" on tax and budget issues. Which is one reason I think it's unfortunate that both our political institutions and the larger political culture in which they're embedded places such a premium on grand bargains. You can easily imagine a healthier approach based on bipartisanship by alternation. The way this would look is that we would have no fiscal consolidation in 2011 or 2012, since none is necessary. But then if Barack Obama was still Prime Minister in 2013, you would do the left-wing version of deficit reduction—higher taxes, technocratic health care cost controls, and less defense spending. The volume of higher taxes the Democrats would want to implement wouldn't suffice to close the long-term gap, but it would reduce it enough to be manageable for a while. Then if at some point the Democrats' approach stopped working and led to an economic slowdown, Republicans would come into office and implement the right-wing version of deficit reduction—benefit cuts in safety net programs and austerity for public workers. Some of the stuff Democrats did would be rolled back, but the most politically and economically sustainable elements wouldn't be. Then at some point Democrats would come into office, and roll back some of the stuff the GOP did, but the most politically and economically sustainable stuff would stick. Then they would do some new stuff and eventually they'd lose.

In many places, I think it's taken for granted that this is how progress is made. In the UK, Labour never wins a definitive victory against the Conservatives and vice versa. Nor is there ever a "grand bargain." But over the long term, public policy reflects both conservative and progressive ideas because people inspired by those ideas take turns trying to govern the country in a way that pleases the voters. America, by contrast, is stuck between people with apocalyptic visions of final victory and unrealistic visions of a "deal" that takes issues "off the table" via bipartisan consensus.

Fannie, Freddie, "The Crisis"

I sometimes don't know what it is people mean by the phrase "the financial crisis" and certainly Tyler Cowen's post in defense of the "blame Fannie Mae" account leaves me scratching my head as to which crisis he's talking about. This, to me, is what "the financial crisis" is:

1. There was a large run-up in property values.

2. Many highly rated mortgage backed securities were created based on the assumption that that a systematic decline in property values was impossible.

3. A lot of financial transactions were undertaken based on the assumption that the high ratings were deserved.

4. Property values declined.

5. Highly rated MBS lost their value.

6. Financial panic!

The part where unwise public policies to subsidize homeownership would seem to come into this is step (1), but we in fact see this happening in many markets (Spain, commercial real estate) where Fannie and Freddie weren't players. Admittedly, about a hundred other terrible economic things have happened over the past four years. But this chain, to me, is the financial crisis. Before the financial crisis, I remember a number of people warning that the problem with Fannie and Freddie was that they could leave the taxpayers on the hook for a lot of money if something went wrong. And, indeed, something went wrong and Fannie and Freddie left taxpayers on the hook for a lot of money. That, to me, seems sufficient to make the case against Fannie and Freddie. But people want this fact to do some kind of ideological work that it won't support. Banking activities need to be regulated or else asset price fluctuations will lead to macroeconomic instability.

[UPDATE] I don't think I want to endorse Brad DeLong's conclusion that Fannie and Freddie made the crisis better. American housing policy is really bad, along a number of dimensions, of which Fannie and Freddie were one and I don't think that does much to help anything. But I see F&F's critics as trying to make the problems with housing subsidies do ideological work regarding bank regulation in a way that doesn't make sense.

Fashion Copyrights: Still a Terrible Idea

When I wrote about intellectual property law ruining Star Trek's utopian scenario of plenty some people responded by noting that recipes aren't copyrightable and patent terms expire. All true, but the point is that the entire framework of intellectual property is a social creation that's changed over time and can change again anytime politically powerful actors want to create some new rents for themselves. For example, "[n]ow five years into a campaign by the Council of Fashion Designers of America to enact some sort of protection for original designs, the proponents of such legislation say they have their best chance yet at seeing a bill become law."

This was a terrible idea when I first heard of it, and it remains a terrible idea today. The issue, as ever with Americans run-amok IP politics, is that nobody can point to the problem here. The article is full of examples of alleged copying which provide the motive for people to want to make said copying illegal. But the question, again, isn't whether a lack of prohibitions on copying will allow for copying. The question is what's the problem? If the problem is that there's no innovation in fashion design, then perhaps time-limited monopoly grants to fashion designers is the answer. But is that a problem? Have high-end fashion houses stopped doing new lines? Do people just not bother to buy new clothes anymore? I've never heard anything like that just as PROTECT IP proponents can't point to any national crisis whereby nobody's recording songs or TV shows.

The Cost Of Independence

I've been reading a lot of lately about the revolutionary period and the early republic, and it's extremely interesting but nothing I've gotten to yet really bores down into the economics of the era. That's too bad, since everyone seems to agree that a background of economic distress in the 1780s was an important element driving the conclusion that the Articles of Confederation weren't working. This research from Peter Williamson and Jeffrey Lindert attempts to quantify just how bad the situation was, observing that "America's real income per capita dropped by about 22% over the quarter century 1774-1800." Since the economy was growing in the 1790s, this implies that the revolutionary period was associated with a terrible depression. In part, that's just the destruction of the war, but also:

This second shock consisted of the disruptions to overseas trade during the revolution and, after 1793, the Napoleonic Wars. Available price and trade data show that the colonies, especially in the Lower South, suffered heavy trade losses as the war deepened, and they recovered only slowly and partially thereafter. In real per-capita terms, New England's commodity exports rose by a modest 1.2% from 1768/72 to 1791/92, they rose by 9.9% in the Middle Atlantic, but fell by 39.1% in the Upper South, and by 49.7% in the Lower South, yielding a decline of 24.4% for the thirteen colonies as a whole (Shepherd and Walton 1976). The most painful of these shocks was the loss of well over half of all trade with England between 1771 and 1791. In addition, America lost Imperial bounties like those on the South's indigo and New England's whale oil. Demand shocks were less evident for products where America had a big influence on European supply. Thus, tobacco and rice revenue losses were smaller since the fall in volume was partially offset by the rise in price. [...]

America's urban centres were damaged by British naval attacks, by their occupation, and by the eventual departure of skilled and well-connected loyalists. [...] To identify the extent of the urban damage, one could start by noting that the combined share of Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, and Charleston in a growing national population shrank from 5.1% in 1774 to 2.7% in 1790, recovering only partially to 3.4% in 1800. There is even stronger evidence confirming an urban crisis. The share of white-collar employment was 12.7% in 1774, but it fell to 8% in 1800; the ratio of earnings per free worker in urban jobs relative to that of total free workers dropped from 3.4 to 1.5; and the ratio of white collar earnings per worker to that of total free workers fell even more, from 5.2 to 1.7. This evidence offers strong support for an urban crisis, and it also supports the view that America had not yet recovered from the revolutionary economic disaster even by 1800.

It all worked out well in the end, but obviously the decision to fight for independence was quite costly. This also seems to cast the view that the framers of the constitutions had economic motives for their actions in a somewhat less sinister and cynical light than is sometimes indicated. "OMG, per capita income in this country is plummeting" is a perfectly respectable reason to want to shake up the political system.

The Next Convergence

Michael Spence's The Next Convergence: The Future of Economic Growth in a Multispeed World is a bit all over the map as a book. But in essence it's one very good book about rapid growth in developing countries and the implication of the fact that it's now happening on a sufficiently large scale as to have macro-impact on the world as a whole. There's lots of other stuff in there that's not as good, but this is one of the most important subjects in the world today so the high points definitely make the book worth reading.

This is why sweatshop manufacturing is so lucrative:

In the early stages, the productivity differentials between the rural and urban sectors are very large. Urban productivity levels normally exceed the rural ones by factors of between three and six times. This is to some extent reflected in income differentials. The flow of people across this boundary therefore tends to produce rising average incomes and rising income inequality. One might reasonably ask why everyone doesn't move to the cities and to higher-income employment once this process gets started. Part of the answer is, they can't. It takes many years for private investment to create the incremental productive employment opportunities and for public investment to build the urban infrastructure. The other part of the answer is that they do move, hoping to capture a place in the new economy. Not all succeed. This normally causes the urban inflow to outrun both the capacity of the employment-generating engine to create employment and the government's capacity to create urban infrastructure. The result is urban poverty and slums, which can be found in many cities in the developing world. Managing this so as to maintain a balance is a large challenge.

The wages paid for low-skill factor labor reflects the average productivity of the economy. But the productivity of sweatshop work is phenomenally higher than the productivity of third world agriculture. Consequently, during initial phases of urbanization you can earn huge profit margins. But as workers are drawn out of the countryside the ratio of land to farmers rises, and with it rural wages. At that point you can still make money running a factory, but the windfall party is over and the country needs to move up the skill/value ladder to keep growing.

July 15, 2011

Serge Ibaka And The Case For Immigration

Serge Ibaka was born in Congo and lives in the United States where he plays for the Oklahoma City Thunder, but he played pro hoops in Spain for several years and can bring much-needed toughness and defense to the Spanish national team. Consequently, they've made him a citizen:

Ibaka must swear loyalty to the Spanish crown and constitution to complete the nationalization process before he can team with Los Angeles Lakers center Pau Gasol and brother Marc of the Memphis Grizzlies in a formidable frontcourt for Spain.

"Pau is possibly the most talented center with the best fundamentals in the (NBA)," Ibaka said. "It will be a dream to play with him."

Spain has Ricky Rubio and Rudy Fernandez in the back court so this is a very potent team. Of course you could see this as a way of taking a job away from a hard-working Spaniard. But a better way of looking at it is that skills are complementary. A higher-performing team featuring Ibaka's talents will be good for all Ibaka's coworkers, the other players, the coaches, etc. as well as for Spanish hoops fans.

663 DC Teachers Getting Raises Thanks To Performance Pay

I wish Bill Turque's column about the latest IMPACT teacher evaluation news out of DC hadn't focused so heavily in the lead and headline on people getting fired. The much more important part is way down:

Another 663 teachers (16 percent) were rated highly effective, making them eligible for performance bonuses of up to $25,000. The vast majority were rated effective.

There's nothing wrong with the government paying high salaries if doing so gets you high quality personnel. If generous salaries mean you get a lot of applicants, that's great. But it's worth looking at whether your hiring decisions have worked out well. And then if they have, you should by all means spend money. It might cost a lot to hire a lot of excellent teachers and keep them teaching in your school system. But that's money well spent. The idea that it's somehow "anti-teacher" to want to identify and compensate the best people in the system is bizarre.

15 Years Of Budget Insanity

It seems to me that it's possible to date the moment that conservative movement thinking on tax and budget issues jumped the shark. The date? August 6, 1996. The issue—Bob Dole's economic plan:

In the face of a steady stream of solid economic news – low unemployment, mild inflation and rising wages – Dole will argue this fall that high taxes are keeping the American economy from realizing its full potential. His plan calls for reducing income-tax rates by 15 percent across the board, creating a $500-per-child tax credit for low- and middle-income parents, halving the capital-gains tax rate on investments, rolling back a tax increase on Social Security recipients, and balancing the budget.

Dole said it's the preamble to an even more ambitious and unspecified plan to restructure the tax system and "end the IRS as we know it" – all while keeping Social Security, Medicare and defense "off the table" from budget cuts.

"The real Bob Dole would wonder how you were going to pay for it," said Martha Phillips, executive director of the Concord Coalition, an anti-deficit group that favors restraining middle-class benefit programs such as Medicare and Social Security. Phillips is a former Republican staff director for the House Budget Committee.

What you have here is a political movement that no longer understands its own theory. Flash back to the 1970s. You have high unemployment. But you also have high inflation. Because inflation is already high, you can't boost growth by boosting aggregate demand. You need reforms that operate "on the supply side" and lower marginal tax rates count. Now we can debate 'till the cows come home whether or not Ronald Reagan's 1981 budget actually had important supply side benefits, but the basic story makes sense. But by 1996, what is the problem that Bob Dole is trying to solve with this tax cut? He's grappling with the political problem of "a steady stream of solid economic news—low unemployment, mild inflation and rising wages." We need supply-side reform because . . . why? Ever since then, conservatives haven't really answered "why" questions about their economic prescriptions. Instead they prescribe a cure for stagflation regardless of the situation. And over time, this scenario has become more and more toxic, such that today they've decided that we are experiencing high inflation even though we're not.

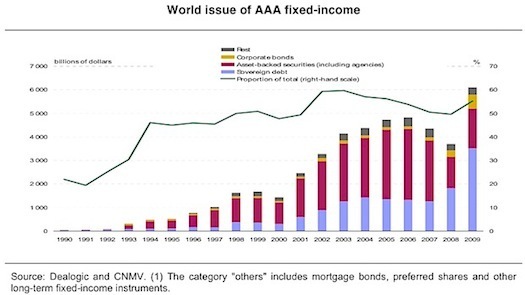

What's The Deal With … AAA-Rated Debt?

This is the chart everyone's writing about today:

Alarming, I guess.

But it reminds me of one of these things I keep being embarrassed to write about given that it does a fair amount to expose my own ignorance. What's the deal with there being all these different kinds of AAA-rated debt? After all, the idea of AAA debt is that it's safe. Like, really and truly safe. But if something represents the maximum level of safeness, then it should all be equally safe. Safe is safe. Which means it should all have the same yield, since the differences in the yields represent differences in the risk level. Clearly, though, different AAA-rated assets don't have the same yields. That's why people wanted to invest in complicated AAA-rated mortgage backed securities. They paid a yield that was sufficient higher than the yield on other AAA-rated debt that it was profitable to take the time to create them. But if the yield is higher, then it's not as safe as the other assets. So how can they all get the gold standard for safety? It seems like a pretty transparent dodge. You have regulatory or marketing reasons to want to have "safe" debt. But safe means low-yield. But higher-yield is more profitable. So you find the least-safe possible "safe" debt. But what's safe about that?

Recapturing The Romance Of Monetary Policy

I had a frustrating back and forth (here and here) with Corey Robin about monetary policy. He's a writer whose work I really enjoy. This 2004 Boston Review piece on neoconservatives is seminal, and his book Fear: The History of a Political Idea is great. But I felt like there was just a disconnect. I'd been asked to write something for The Atlantic, so I wrote something couched in technocratic language, and Robin was really objecting to me on thematic/ideological grounds and I wasn't doing a good job of rephrasing in the right mode of discourse.

Mike Konczal offers perhaps a better tack, noting that engagement with monetary issues has historically been at the heart of American politics:

But going back to the Cross of Gold speech, through Franklin Roosevelt's abandonment of the gold standard and aggressive price targeting, progressives and liberals have had a long-tradition with monetary battles. These battles have disappeared from the agenda, but it needs to come back as we have the right answer: money is a social creation, one that the government has a responsibility to use to stabilizing growth, prices and full employment with a view towards building a future without overheating the system or letting it choke to death from a lack of oxygen.

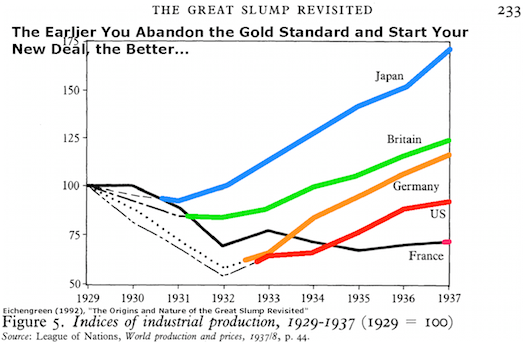

And this goes back. Both the Washington and Jackson administrations were dominated by what amounted to disputes over monetary policy. Part of what I think goes wrong in the contemporary left's understanding of this is that people have a kind of romance with the idea of the Works Progress Administration. The WPA not only helped as a relief and recovery measure, but it also instantiates progressive values about social solidarity and the importance of public investment. It's important to understand, however, that lurking behind this fiscal measure is a monetary one. Under the fiscal system that prevailed between the wars, the government's ability to spend money on public works was limited by its ability to get its hand on gold. This is why leaving the gold standard is so crucial, both here and abroad, to launching recovery from the Depression:

Here in the contemporary United States, meanwhile, it's important to understand that any demand-side solution to mass unemployment necessarily involves the central bank tolerating more inflation. That's because even in an economy with lots of excess capacity, lots of unemployed workers, etc. we still have some objective scarcities. If more people had jobs, they'd have higher incomes, and they'd try to buy more stuff. Some of that "stuff" would be things that are objectively scarce (gasoline, e.g.) and prices would go up. This would be a small price to pay for a huge reduction in human misery. But if the central bank isn't willing to pay the price, it won't work. Strict inflation targeting would mandate cutting the recovery off. It's interesting to speculate as to whether more aggressive targeting on the part of the central bank would be sufficient as well as necessary, but it's unquestionably necessary.

So to go back to the romance. Separate from and prior to the ideologically freighted question about how exactly the government should try to bolster aggregate demand is the question of whether this should be done at all. Because we've turned monetary policy over to "technocrats," it's become a question that's treated as "technical." But unless the answer is "yes," then you can't make any of these other projects work. But historically in the United States, the monetary question hasn't been treated as a technical one. And in the contemporary United States, the right seems to have recaptured an understanding of it as an ideological one. Michele Bachmann is the populist right-wing hero du jour and Paul Ryan is the technocratic right-wing hero du jour, and they're both pounding the pavement for "sound money" and a "strong dollar." What this looks like is already playing out in Europe. If you want more real output without any increase in prices, the only way to achieve that is to make things cheaper — lower wages and deregulation, or else lower taxes and reduced services.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers