Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2246

July 11, 2011

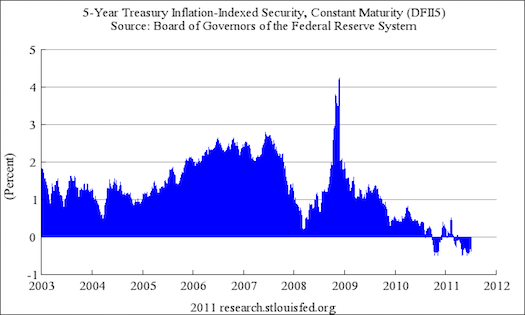

Real Interest On Government Debt Is Negative

Karl Smith observes that the flight to quality has become so severe that the real interest rate on some classes of government debt is negative:

Suppose the government had two choices. It could either pay for infrastructure improvements as it went along out of tax revenue or it could borrow money build the infrastructure now and then repay the money with tax revenues. Ordinarily the question would be, does the advantage of building quickly outweigh the cost of the interest. However, right now the interest cost is negative. The government saves money by borrowing now rather than waiting and paying cash. Let me say again because I have noticed that this goes against so much intuition that its hard for many people to wrap around when I first say it.

In a sane political environment, Washington would be obsessed with the question of how much can get done within this window. How many projects is it logistically possible to complete quickly enough to take advantage of the cheapness of debt. Instead, we're attempting to resolve thorny and ideologically freighted questions about the long-term trajectory of the welfare state even though resolving these issues won't change anything about the present environment. It's weird. It's sad.

Economically Strong Metro Areas Have Added Government Jobs, Weak Ones Have Shrinking Public Sectors

[image error]

Private sector job growth has been doing okay for the past year. Not great. And we really need a stretch of "great" performance to soak up the huge number of unemployed people. But still: It's been okay. As I've been emphasizing, the problem is that month after month, we have this so-so job growth in the private sector clawed back by big-time cutbacks in state and (especially) local government. A recent Brookings report looking at the recovery on the metro area scale again confirms the centrality of public sector trends:

Nearly all the metropolitan areas whose economies suffered the least since the start of the Great Recession had increases in government employment, while most of those that suffered the most lost government jobs. Seventeen of the 20 metropolitan areas that have had the strongest overall economic performance since the start of the recession (all except Augusta, Buffalo, and Columbus) gained government jobs since their periods of peak total employment. Fourteen of the 20 that had the weakest overall performance (all except Bakersfield, Boise, Cape Coral, Jacksonville, Lakeland, and Tampa) lost government jobs since hitting their total employment peaks.

The structural shift away from government work is something conservatives claim to want. But the overall impact of shedding public sector workers in a high unemployment environment is quite negative.

Targeted Tax Breaks Are Government Programs

Alex Tabbarok attempts to defend the conclusion that something like a 529 tax-empt savings vehicle doesn't constitute a government program. "A 529 program is not a government program like food stamps," he writes. "It is the absence of a government tax."

Well, look, the University of California system isn't a government program like food stamps, but it's still a government program. Programs exist in many forms. One such form is special tax breaks for this and that. It's (perhaps) true that "[i]n a laissez-faire world we don't get rid of 529 programs, instead all savings, not just savings for college, become tax-free," but I don't really see what this has to do with anything. We don't live in a laissez-faire world, and we've never lived in a laissez-faire world. In a laissez-faire world, there's no government-sponsored exploration of the Western Hemisphere, there's no expropriation of Native American land, there's no I-95, there's no copyright protection for Professor Tabarrok's books, there's no limits on immigration of foreign economics professors, etc. It might be an interesting exercise to pick some arbitrary moment in human history and speculate as to what would be the case counterfactually today had it been the case that laissez-faire principles were consistently applied from that moment forward. But in the world we have, there's nothing but a set of public policy choices undertaken by various actors for various reasons. Trying to evaluate the existence or non-existence of government programs with reference to whether they would hypothetically represent a selective failure to depart from a hypothetical laissez-faire status quo ante doesn't make sense.

Scientific Proof That Rebecca Black Was Right

John Helliwell and Shun Wang report on the happiness increasing properties of the weekend (this is via Annie Lowrey):

This paper exploits the richness and large sample size of the Gallup/Healthways US daily poll to illustrate significant differences in the dynamics of two key measures of subjective well-being: emotions and life evaluations. We find that there is no day-of-week effect for life evaluations, represented here by the Cantril Ladder, but significantly more happiness, enjoyment, and laughter, and significantly less worry, sadness, and anger on weekends (including public holidays) than on weekdays. We then find strong evidence of the importance of the social context, both at work and at home, in explaining the size and likely determinants of the weekend effects for emotions. Weekend effects are twice as large for full-time paid workers as for the rest of the population, and are much smaller for those whose work supervisor is considered a partner rather than a boss and who report trustable and open work environments. A large portion of the weekend effects is explained by differences in the amount of time spent with friends or family between weekends and weekdays (7.1 vs. 5.4 hours). The extra daily social time of 1.7 hours in weekends raises average happiness by about 2%.

Extra government-mandated three day weekends could be costly in terms of overall economic output, but would seem, on this basis, to have substantial hedonic benefits. But it also serves as a reminder that many of our social and economic arrangements are more tenuously grounded than we like to admit. The series of events that's led to the convention that an ordinary full-time worker is expected to have a ratio of 5:2 workdays to days off is pretty arbitrary. What if the French Republican Calendar had taken off as well as the metric system and most countries were doing ten day weeks? We'd probably have a 7:3 ratio and be working a slightly higher proportion of days.

Greek Default Could Be Globally Devastating

Over the weekend I was reading Heather Stewart's article on how default worked for Argentina and might be the best choice for Greece. I think there's a lot to be said for that argument, but she misses some differences in the situation. In particular, Argentina's not in a currency union with anyone. If Greece defaults, by contrast, that will put serious pressure on Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and now even Italy is feeling pressure.

Italy doesn't have a reputation as an economic powerhouse, but it's one of the world's top 10 economies with more output than India. For Italy to default would be a gigantic, globally meaningful event with disastrous consequences for lots of people. And that's why the stakes are so high for Greece. It doesn't change the fact that default may well be the best choice for the country, but it would be much more momentous than anything Argentina's ever done. The real lesson, then, is that this really is a continent-wide problem that needs an EU-level solution.

Debt Overhang Makes Housing Prices Key To Recovery

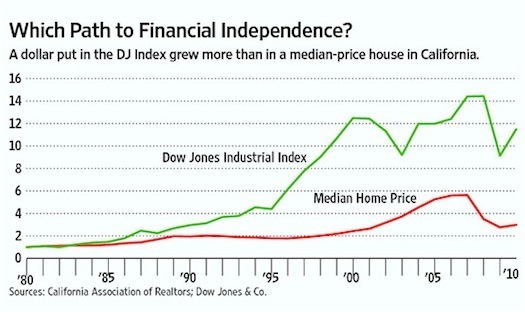

Robert Bridges has an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal dedicated to showing that homeownership is not a particularly savvy investment, illustrating the point with a look at California:

That seems about right. A "house" is typically a bundle of a depreciating consumer durable good (the actual house) and a speculative commodity (land). It's possible, clearly, to make money with speculative investments in commodities. People make money speculating in gold, people make money speculating in oil, and people can make money speculating in land. But there's no reason to think that amateur investors will do systematically better as land speculators than as speculators in anything else. The general advice that if you're not an expert, you'll do best to hold a diversified portfolio seems sound. Talk about "houses" tends to obscure what's actually happening here.

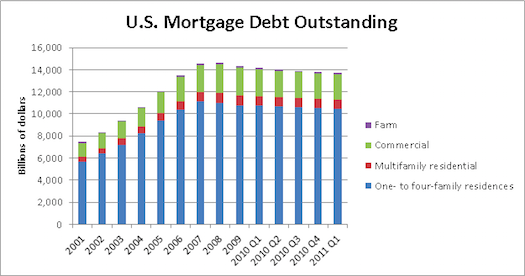

But Bridges goes from that sound point to criticizing the idea that bolstering house prices can be useful in promoting economic recovery. In his telling, political interest in doing so is all interest group politics. But there's a very real issue here, namely debt:

As houses got more expensive, people took out larger loans to buy them. Then the prices started to fall. But a person who owes $200,000 to the bank and owns a house worth $200,000 is in a very different position from a person who owes $200,000 to the bank and owns a house worth $150,000. Efforts to juice home prices are, in part, about efforts to eliminate this debt overhang problem. As it happens, I think it's not a very sound approach. The better ideas would be either principal reduction or, even better, 4 percent inflation. A return to Reagan-era levels of inflation would speed the deleveraging process without increasing the cost of housing to the non-indebted. The real issue here is that the "reinflate the bubble" strategy is the most bank-friendly approach.

Michigan Woman Faces Jail Time For Vegetable Garden

Here's a weird story out of the suburbs of Detroit where a woman is facing jail time for planting a vegetable garden in her front yard, which local officials have decided violates the rule mandating suitable live plant material.

The fact that this kind of thing doesn't seem to prompt much in the way of outrage from the very same people who are scandalized by increased regulation of light bulbs tells you a lot about American politics. For one thing, there are several giant industries willing and eager to put up lots of money to fund people to complain about the work of climate change activists, so these stories get blown up. But it's also just a reminder that, in practice, things like support for free markets, belief in freedom, hostility to government regulation, support for small government, etc. play no actual role in American politics. It's interesting that the political movement to which a plurality of Americans belong likes to talk a lot about these ideas. But there's no nationwide tea party backlash against lawn regulations. The very same impulses that lead people to dislike the idea of new regulations forcing some change in their life lead the very same people to love the idea of old regulations that prevent other people from impinging on their psychic serenity.

I think John Boehner's complaint that Barack Obama is "snuffing out the America I grew up in" was very telling as to what politics is really about. Back when Boehner was a kid, tax rates were much higher, gays were in the closet, women were in the kitchen, nobody listened to hip-hop, and a black man in the White House was a science fiction scenario. He feels nostalgic about it, and would probably be mad as heck if hippie locavores started planting vegetable gardens all over his neighborhood.

Math And Literacy Are Vocational Skills

There's something very strange about the conversation around vocational education in the United States, well captured by the fact that Motoko Rich's article on cuts in federal spending on vocational skills posits a disjoint between job training and reading:

In European countries like Germany, Denmark and Switzerland, vocational programs have long been viable choices for a significant portion of teenagers. Yet in the United States, technical courses have often been viewed as the ugly stepchildren of education, backwaters for underachieving or difficult students. In a speech to the National Association of State Directors of Career Technical Education Consortium in April, Secretary of Education Arne Duncan said that "at a time when local, state and federal governments are all facing tremendous budget pressure" advocates for vocationally oriented education "must make a compelling case for continued funding." In his camp are those who say students need to concentrate on basics like math, literacy and history to prepare for college and the jobs of the future, rather than learning a narrow technical craft. In this view, bright students like Mr. Kelly, who have the potential to do college-level work, should be put on that path, or schools will have failed them.

It seems to me that there's a gaping void out there between "students need to concentrate on basics like math and literacy" (forget history) and "students need to go to college." Literacy is a very important life skill. It's difficult for me to think of a job for which literacy wouldn't be a useful skill to have, and of course it's not like you see retired people sitting around saying, "Now that I'm out of the labor force, I never have occasion to read." Students need to concentrate on literacy so that they know how to read. Math is similar. I visited a vocational school in Helsinki where they were training people to be stylists. They were learning about makeup and manicures and haircutting. But they were also learning some accounting. There's no reason to think someone has to go to college to someday start her own hair salon, but it helps a lot to know something about how to keep the books. And, again, not only is math a vital skill here but literacy is going to help you a lot in terms of researching the market, what it takes to start a business, etc.

It seems at least plausible that a vocational setting of some kind might be the most compelling setting for some people to learn these basic academic skills. Certainly there's something a bit odd about some of the aspirational "everyone must go to college" rhetoric out there. But we need to keep in mind that at the low end, the outputs from the American educational system are currently really really bad. It's not about everyone needing to have basic reading and math competency so they can go to college; it's about everyone needing to have basic reading and math skills so that they know who to read and do basic math.

There's Something About Money

In terms of the ideological origins of monetary confusion, I think Paul Krugman's got it right. If you think redistribution of wealth and income is wrong, it's easier to support that idea if you believe public policy has no role to play in stabilizing the economy. And you can really only believe that by confusing yourself about how monetary policy works.

But there's still an issue of why these topics are so confused on the mass level. And I think the answer here is largely linguistic. Krugman's column about the Capitol Hill Baby Sitting Co-Op is one of the best popular explanations of monetary policy ever written precisely because there's no "money" involved in it. It's just co-op scrip. Which helps because the language around money is very confusing. People say things like "Mark Zuckerberg has $9 billion" when what they mean is that Mark Zuckerberg has an equity stake in Facebook that's worth $9 billion. Which is to say that normally when we're talking about "money," we're talking about the accounting value of real assets. But monetary policy is much more about shortages of the medium of exchange. People say things like "the money has to come from somewhere," which makes very little sense if you think about it literally. Real resources have to come from somewhere. And in a deep recession, real resources are left idling over the country. But to mobilize the real resources may take more money. Print up some dollar bills and start handing them to unemployed people to go do things, and real output will rise. The dollars come from the U.S. Mint, which is the only place they can come from. Or imagine if all the ATM machines and credit and debit card swipers in the state of California stopped working. All the workers, skills, shops, offices, equipment, skills, etc. would still be there, but output would collapse as people started hoarding the existing supply of currency.

Policymakers Can And Should Take The Easy Way Out On The Debt Limit: Just Raise The Ceiling

As we wait for President Obama's nine hundredth press conference about debt ceiling negotiations, it's worth reviewing the formidable structural barriers to making a deal. The biggest stumbling block is that Republicans are uniformly opposed to increasing tax rates and nearly unanimous in their opposition to closing tax loopholes. A smaller stumbling block is that some large segment of Democrats is deeply hesitant to cut Social Security benefits. A Politico story today reminds us that House Republicans don't want to cut military spending any more than House Democrats want to cut retirement payments. What's more, the House Republicans are riven by intra-caucus dynamics such that John Boehner doesn't want to agree to anything Eric Cantor hasn't agreed to since that would open the door for Cantor to challenge him, but Cantor doesn't want to agree to anything since that would entail giving up the chance to challenge Boehner.

Surveying the scene, perhaps everyone should take a deep breath and recall the traditional way the country has avoided default when the debt ceiling needs raising: Congress raises the debt ceiling.

It's that simple. The same kind of "clean" debt ceiling increase that's passed repeatedly over the past 100 years will allow the country to avoid default without tax increases, without defense cuts, and without slashing entitlement spending. Education will be spared. So will transportation, health care, farm subsidies, and everything else. The interest rates investors are charging the American government to buy our debt are extremely low right now. The world economy is suffering from an excessive demand for American debt, not by reluctance to lend. All we need to do to keep our finances flowing is to raise the statutory debt ceiling. At some point, things will change, and we may face a crisis that requires bipartisan dealmaking and "tough choices." Right now, though, the only crisis we face is an entirely self-created one. House Republicans wanted to create a hostage situation to force President Obama to propose steep spending cuts. But when Obama came to the table with a proposal for steep cuts, it turned out that Republicans don't actually want to sign a bipartisan deal. Which is fine. Don't sign a deal! The absence of a deal in no way forces a crisis. Just raise the debt ceiling, fight the 2012 elections, and pick up the long-term budget issue then.

The world has plenty of problems on its plate right now. The long-term U.S. structural deficit isn't one of them. The expiration of the Treasury Department's borrowing authority is one. And the latter problem can be solved without addressing the former.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers