Scott Berkun's Blog, page 8

December 26, 2017

How can you tell a wise person when you meet one?

On Tuesdays I write about the top voted question on Ask Berkun (see the archive). This week’s question is from Mike: How can you tell a wise person when you meet one?

If you can’t judge a book by its cover, how can you judge a person on their first impression? I’ve never liked the cliche about “you never get a second chance…” because it’s rarely true. Sure, if you spill a grande coffee on someone’s lap, or set an entire dining room on fire, that would be tricky to recover from on a first date, but most first interactions with people are terribly bland, no matter how wise either of you are. There just is no secret wise-person handshake nor a wise-person detection app for your phone.

Instead it takes an actual conversation with someone to learn who they are and how wise they might be. Starting conversations isn’t that hard, but there is a stupor that comes over most of us when we meet new people. Mostly, it goes like this: “Hi, how are you?” “I’m fine, you?” “I’m fine, thanks” . There’s not much chance to notice a wise person here. Our questionable social skills with strangers means there are hundreds of wise people we have met at parties, or stood next to at the bus stop, and never knew it.

I understand social anxiety and fear of embarrassment, but yet it’s still mystifying that after 10,000 years of civilized life our species still hasn’t recognized how little there is to lose in talking to strangers (in safe situations). Why not just assume they are wise or interesting? What is there really to lose if you’re wrong? It’s easy to end conversations with strangers and they likely didn’t even expect you to start one. Therefore, why not make an offer to get outside of the boring conventions of daily life we so often complain about? More to my point, it takes a bit of wisdom about wisdom to find wise people.

Wisdom means not only experience, but an understanding of how to apply life experience (the past) to the present. This means the most likely way to identify a wise person is to have a conversation about life, which likely means to talk about a shared, or personal, event that has already taken place. It’s in their own observations that their wisdom or insight will be revealed (or not). This could take the shape of lessons learned, of attitudes about relationships or work, or thoughts about regrets and future dreams.

Now it’d be weird to go up to a stranger, introduce yourself, and demand “tell me a personal story that reveals how wise you are”. Don’t do that. But in most social situations there is a fast path towards sharing stories. For example, at a party you can always ask anyone you don’t know: “how do you know ” which almost always has some kind of story as an answer (and you can show your curiosity by asking interesting questions about their story). And then you can reply with your own answer, but add some leading context that hints at a story, or question, of your own. Perhaps “We went to college together a decade ago, but I have to admit I’m not sure I belong here. There’s just too many people I don’t know.” Or even ask for advice about how to meet new people at events like this, a fun meta-trick (as by asking this to a new person you are using the question itself to solve them problem).

Perhaps my party socializing advice seems bound to fail, and you might be right. Maybe it’s easier to start with people we already know, like friends, coworkers and family. But even then there must be some kind of inciting event to wake another person up out of their daily routines and pay attention to the fact you are offering a more interesting kind of conversation. There is no guarantee they’ll be interested, or even understand that this is what you are offering. Yet if you don’t try, you’ll never know if you just overlooked a wise person. Someone has to (kindly) incite the chance for insight. To find wise people, you have to be wise enough, or perhaps just sufficiently bold, to reach out for them.

Part of the challenge in finding wise people is what we perceive as wisdom is filtered by the chemistry created by our personality meeting the personality of another. Someone can be very wise, but also irritating. For example I suspect Socrates, for all his wisdom, wasn’t particularly easy to get along with (yet the meetup group that bares his name can be a great way to meet wise people). Maybe you meet someone wise, but they offer their wisdom in a way that makes you feel belittled. Or they have bad breath, which you despise. Or maybe you don’t like their sense of humor, which diminishes your interest in their sage like thoughts. Just because they are wise doesn’t mean their wisdom will be palatable, or even comprehendible, to you.

If I had to list traits of someone wise, they’d include:

Experienced – they’ve had interesting life experiences, both successes and failures, and they’ve asked good questions about them

Humble confidence – they have clarity to share, or to challenge my thinking, but without a strong need to convince me of their view

Insightful opinions – their thoughts invite consideration or raise my curiosity (even if I don’t agree with their conclusions)

(I very much want to list a good sense of humor, but I’m convinced that reflects my own biases)

Which leads to the observation that wisdom isn’t a universal attribute. Some people are very wise about business, but are terribly ignorant about how healthy relationships work. Or they can give fantastic advice about life to others that they fail to practice in their own lives (a notorious failing of gurus, experts and authors too). The singular word wisdom doesn’t stretch to cover the complexities of how it, or it’s absence, plays out in a person’s life, or in the advice they give. People in their later years certainly have more life experience to work from, but that by no means guarantees they possess any more wisdom about life than someone much younger than they are: a person might accumulate ignorance, or bitterness, at the same, or a faster, rate than wisdom.

In the end, mostly what we want are interesting people who are interested in us. Who are friendly, perhaps charming, willing to share what they know and perhaps willing to listen for wisdom they don’t have in new people they meet. Framed this way the titular question of this essay is less daunting. Once you befriend one person with these attributes, it’s easier to find more. And who knows, maybe while we’re trying to find what we need, now and then we can be the “wise person” someone we meet (at a party) is looking to find.

Where have you met the wisest people you know? How did you recognize them? Leave a comment.

December 19, 2017

The Last Jedi and Suspension of Disbelief

[There’s no askberkun post today – hope you enjoy this timely essay on films and expectations. There are no spoilers about The Last Jedi, but I’ll allow them in the comments.]

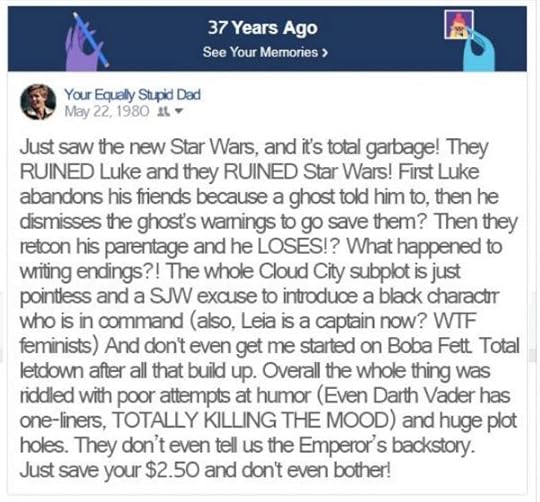

We love or hate films based on what we expect of them. It’s easy to blame a movie’s creators, as we are their customers, but in reality half the work is ours. Do you want realism or an escape? Do you want to be satisfied or challenged? To think or to laugh? What rules from real life must be followed or do you want broken? Too often we leave it until we’re midway through a movie to realize that what we wanted wasn’t what we thought we wanted and we rarely blame ourselves for that mistake.

Two decades and ten films into the world of Star Wars I find my expectations hard to manage. I thought Rogue One, The Force Awakens and The Last Jedi were good “Star Wars films” but what does that even mean? It’s hard to watch any of these films now, new or old, without thinking at various moments about how it ties together, or cuts against, the history of the series. This is part of the fun, but it’s also a trap. These are now meta-movies. They are, as Lucas intended, serials, like the cliffhanger shorts he was inspired by, but is that what I really want watch? I’m not sure.

It’s hard to experience any event, or character, no matter how well done, in a Star Wars film as if it exists in it’s own time in it’s own ‘real’ universe. The burden of Star Wars (and most film series than span generations like Terminator, Indiana Jones or Spiderman) is any story you are watching is burdened by narrative masters that lurk in the shadows off-screen, in our memories. And franchise reboots only complicate the expectations game, playing on and against our expectations in both interesting and frustrating ways. I want to just watch the film in front of me, free from too much context, but that’s not the world these films put us in anymore.

All movies depends on the audience accepting a departure from their daily lives. We know these are actors on movie sets inventing a false reality. Mostly this departure is what people are paying for: an escape of one kind or another. Even the act of sitting in a full theater itself, sharing an experience with others, is something we don’t do often in life anymore. Consider the ritualistic decent into shared silence as the previews end and the feature film begins: when else in life are we in grand rooms with hundreds of strangers who all agree to respectfully share the silence? It’s evidence that everyone has reverence for the powerful shared escape of film.

Coldridge coined the term suspension of disbelief to describe the desired state of mind a reader, or viewer, needs to have for the work of art to function. But the question is: who should do the greater burden of achieving this state of mind? The creator or the consumer? We assume it is the creator, and they do have the lion’s share, but if the consumer is not in the mood for Shakespeare, or Amy Schumer, is there anything Shakespeare (or the director of the particular play) or Amy Schumer can really do about it? Films, like most commercial art, make promises in their advertising and marketing, but our expectations, when we sit in that chair and the film begins, are still are own.

More to the point about Star Wars: the endless arguments about plot lines and holes, boneheaded choices by lead characters, or story arcs that go nowhere reveal the arguers chosen position on the spectrum of disbelief suspension: they only want to disbelieve so much, as in “YES, movies with time-travel, or zombies, are fine. And in Star Wars, it’s OK that a long time ago spaceships somehow operated on different principles of physics, a power exists that unifies the universe in such a way that people can use it move objects with their minds, but NO a Starkiller base couldn’t possibly work.” Even when we criticize the inconsistencies of a film, we forget that we’re partly responsible for the rules we’re expecting a fiction to be consistent with.

Part of the value, in fables and fantasy, of bonehead choices and challenges to logic is the gift of superiority it gives to the audience. It’s straight out of the classic soap opera and hero myth narrative playbook to inspire the audience to judge mistakes, to debate flaws, and to be enraged by them. “What! They had an evil twin?” is well known as one of many standard genre tropes for soap operas and films, but even the Iliad expects us to accept the plausibility of a (successful) Trojan horse, the power of Helen’s beauty, and even begs the reader to criticize the hero Achilles (although perhaps not the supernatural nature of his powers).

And each person has their own, often subconscious, list of expectations they never want violated. Some of these rules, like say, the limits to how the force works, or what is allowed to happen to certain characters, feels fair as it’s defined by the legacy of the films themselves. If James Bond could suddenly fly, or Wonder Woman turned out to be an an alien robot from the future, the shock would be understandable (although comic books notoriously introduce shocking plot lines that violate rules). But if a story that has always had the same flaws continues to have them, and there is outrage, who’s problem is it really?

For all the worship of Campbell’s Heroes Journey, a model of storytelling Lucas claims to have used in on his final drafts of the original Star Wars, there’s something shallow about it’s advice. Stories based on universal themes, that are told in a universal way, tend to overly simplify the complexities of good, evil, love and hate. There are rarely “bad guys” and “good guys” in life in the way these stories suggest (and to be blunt, the evil of the bad guys, and good of the good guys, in Star Wars is never explained well, as explaining it is not a strength of this idiom. Luke and Rey could just as well have been “evil” given their rocky starts in life). Is this a problem or an advantage? Well of course it depends. Do you want a soap opera about a far away galaxy today, or a factual memoir by a refuge from a war torn country? A slapstick comedy or a family drama? Do you like the suspension of disbelief mythology and fantasy require, or do you want the down to earth reality of a good documentary about a topic you know well?

One meaning of the word idiom is a mode of expression, or a set of rules for what an audience can expect. Star Wars from the beginning was a fairly tale, a space opera, by design, not caring much about science (e.g. spaceships can’t make bank turns in space, nor make sound), logic or military strategy. Those attributes might be expected in a war movie like Saving Private Ryan, but that’s not the kind of universe Star Wars was created for and thrived in. Arguably a great film transcends idiom: it magically draws you into it’s world regardless of your preconceptions, boosts your suspension of disbelief through filmmaking craft, but that is harder to do in story that’s being told in installments over 40 (or more) years. Which leads to the question: if you saw a random Star Wars film without knowledge of any of the others, what complaints would you have?

Running jokes about how stormtroopers have terrible aim are good because they strike at a truth about the series and the genre. Another is the how heroes regularly pilot spaceships, including freighters, at high speed in impossible turns (that violate physics) through jagged landscapes and spaceships, ones they’ve never seen before, defies any understanding of science or human performance (assuming of course these characters are human at all). Flash Gordon (a major Lucas influence) had similiar problems and so does Indian Jones or The Fast and The Furious or any story with an action hero as the star, as if they die the series ends, but if there is no drama, our disbelief is broken, or we’re bored.

The grand trap might just be that as the age of Star Wars’ first audience matured into adulthood, we backfilled more mature expectations into it. The mythology shifted into religion as the literalness adults crave took control over the generous imagination of youth. For this reason we take seriously story details that were never quite meant to be taken that way. In Greek Mythology, the god Athena was born from the head of Zeus, but to my knowledge there is no reddit forum yet that debates how impractical (or not) this mostly metaphorical plot note might be. We criticize movies that explain too much as having too much exposition, but in fantasy if you start explaining things you chip away at the unreality of the whole thing.

The Star Wars prequels were of course terrible in many ways, but one perhaps noble failure was it’s attempt to make the Star Wars universe sophisticated, nuanced, mature, something more than a fairy tale. Lucas did this of course in direct conflict with the originating idiom the films were born in (most notably the tragic introduction of midi-clorians), but was he wrong to try? I’m not sure. Had the film’s fundamentals of plot, writing and acting been sound, the (now) adult fan base might have widened their suspension of disbelief to allow for more mature kinds of storytelling, even within the context of a fairy tale. But now we will never know, and the series is burdened by the resulting damage (in a similar way The new Star Trek and Hobbit films have burdened their series too).

I found The Last Jedi to be both frustrating and liberating. As a movie I think Rian Johnson and his team did a fine job. They made a “good Star Wars” film. Given the truly otherworldly baggage they inherited they both took more risks, and yet respected the idiom, enough that I’ll keep watching, and for films of this kind I’m not sure what other opinion there is that matters.

The lesson in all this about suspension of disbelief is that it can be thought of as an exercise of imagination. For every plot flaw, every stupid choice a hero makes, for every consistency violation, we can play the generous game of filling in the gaps ourselves. Let’s assume there is a good reason for this, and if I need it I can create one myself, even if it’s not shown on screen. Our brains do it for us most of the time when we sit in a theater, but I advocate helping it along. This can be far more fun than tearing films apart (which is certainly fun too) as we go to theater hoping to escape, rather than to devise ways to ruin the attempt.

But of course we don’t go to movies to obtain homework. I agree we should expect much from the people who take our money for their movies, books and art. But in the end we choose which tickets to buy. By now we know very well what, at its best, the world of Star Wars can do. And there is far more pleasure to be gained by offering generous suspension of disbelief and by matching our expectations, to the idiom of the movie we’re choosing to go see.

[Last Jedi spoilers are allowed in the comments: so view them at your own risk]

December 12, 2017

Why Remote Workers Fail

[On Tuesdays I write about the top voted question on Ask Berkun (see the archive). This week’s question is from Regina [330 votes]: What gaps in communication exist in global virtual teams? Which I have simplified for your reading pleasure to why remote workers fail.]

The best argument about the viability of remote work is that it’s about results: any boss should let their good employees work remotely on a trial basis and see how it goes. If they can perform just as well, and their coworkers have no complaints, what’s the problem? You lose nothing and have a happier employee. Sadly many managers are afraid to try new ideas of any kind, which suggests they’re not all that great at being the boss anyway, but that’s a topic for another post.

Even when a remote experiment is done, and it fails, often it’s the remote worker, or the very idea of remote work, that gets scapegoated. This is sad. It’s far wiser to start by blaming the manager instead. Why? Well the Leffert’s Law of Management states that the starting assumption for managers should be that whatever is going wrong is their fault, and this rule applies to remote work too. A good boss realizes it’s their job to create an environment their staff can perform well in and remote work is just another scenario they should be taking responsibility for.

This sets the stage for the five most common reasons why remote workers fail:

No ally in the main office. If there is a primary physical office, it’s hard for remote workers to know what they’re missing. Someone has to look out on their behalf in meetings, hallway discussions or post work happy-hour chats. No one likes having their time wasted, but without an ally decisions are often made that are not communicated to remote workers, even when those decisions directly impact them. It’s not hard to learn the habits of being an ally, but someone has to lead the way. Some workplaces adopt a remote-first culture, where as many discussions, meetings and processes are done online, and with tools that can be used from anywhere and at anytime (which often benefits “non-remote” workers too, as all conversations are archived and searchable, people can be more productive when traveling, etc.). The boss is the most obvious ally for a remote worker, making sure their perspective and needs are represented.

Cultural bias towards caution. Amazon and other companies talk about bias towards action as a key part of their culture. This means the default posture every employee is expected to have is to be aggressive in making decisions and taking action, rather than waiting to be told what to do or taking endless precautions before acting. Remote workers are more likely to do well in these cultures, as their autonomy becomes an advantage, rather than a source of frustration. Bias towards action also tends to create more resilient employees who are comfortable identifying and solving problems (including perhaps diagnosing co-ordination frustrations involving remote workers). The more overhead and coordination required by a culture, the more pressure that’s put on remote communication tools and the team’s ability to communicate well (see #4).

Poorly defined role. Remote workers benefit from clearly defined roles where they have more freedom to decide on their own how best to use their time and resources. Even if their role requires high collaboration with other people, explicitly stating what’s expected, what powers they have and how their performance will be measured is essential to their success. Of course poorly defined roles are a problem in any organization, but the negative impact is amplified with remote workers. A role likely needs to be reevaluated, and possibly modified, when it’s transitioned to a remote position.

Poor culture of communication. When you work remotely you depend heavily on written communication: email, chat rooms, and more. Organizations that have cultivated excellent communication skills make it much easier for people to work remotely, as it’s built into the culture to ask clarifying questions, to be helpful to coworkers and to document processes and decisions in a way that other people can easily comprehend. One of the great discoveries I made when I worked for WordPress.com (Automattic Inc. is 100% remote) was how thoughtfully everyone wrote and read, and at every level of the organization. It’s taken for granted that most organizations in the world consistently hire people with good communication skills, but in reality good/mature communication skills are uncommon, and the price paid for poor communicators is amplified for remote workers.

The wrong person was hired. Hiring good people is hard enough, but to hire someone for remote work demands extra care. Remote work isn’t for everyone. Some people depend on the energy they get from being physically near their coworkers, or the psychological value of going to a physical place to “do work” and leaving to go home. Remote workers often need above average organization skills and self-awareness of their working habits. Being proactive as a remote worker is a major asset, as even in an organization with allies and a bias towards action, remote workers by definition must take more responsibility for themselves than other employees do. Automattic wisely hires by remote trial, which makes a candidate’s remote working skills part of how they are evaluated.

Despite the suggestion of the image shown below, it’s uncommon for remote workers to fail because they abused their privileges. Many people who choose to work remotely greatly appreciate not having to commute in traffic, value the ability to easily take care of their family (if they work from home) and the superior control they have over their lifestyle when compared to more conventional employment. It’s for these reasons I advocate workplaces give it a try and for people to ask for it. There’s much to gain and little to lose.

Have you seen other reasons why remote workers fail? Have a theory? Leave a comment.

Related:

The Year Without Pants: FAQ about the book about my time managing a remote team

Study finds remote workers often feel left out

Why remote work thrives in some companies and fails in others

Why isn’t remote work more popular

Out of Office: more people are working remotely

November 28, 2017

Why The Right Change Often Feels Wrong

On Tuesdays I write about the top voted question on Ask Berkun (see the lovely archive). This week’s question came from J.R. [via email]:

What is a favorite theory that you wish more people understood?

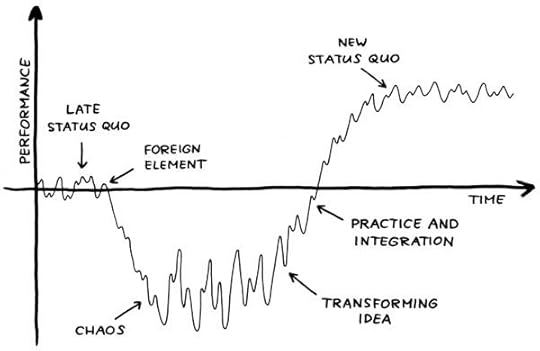

A favorite theory I wish was more well known is the Satir Change Model. It’s popular in some circles, but often when I mention it in talks at events few have seen it before. Virginia Satir was a family therapist who studied how families behave, and in particular, how they respond to change.

We like to believe change and progress are predictable, especially if we’re applying an idea we’ve used before or that is widely accepted. But according to her research (based on family behavior), and her model, even when we’re making the right change, at the right time, confusion and fear are likely.

The Satir Change Model is simple and has 5 parts (image source):

Late Status Quo – this is the present, where things are stable, at least in the sense that they’ve been the same way for some time.

Foreign element – This is Satir’s term for any change that is introduced, which could be something deliberate (a new healthy diet) or something surprising (new neighbors move in next door). It could be a new idea, process, team member or anything. Often people resist foreign elements, even if they come with the promise of solving a problem. People often prefer to keep doing what they have been doing (status quo), even if there are things they don’t like about the status quo, especially if they don’t have much trust in their leader or their coworkers.

Chaos – (IMO this is the central idea of the model). Even if you are doing everything right, and the change is the right one, volatility will rise for a time. Average performance will drop as people experiment with adjustments to incorporate the new idea. Hidden assumptions, and emotions, will be revealed, which can be painful at first. A new idea may require new conversations, redistribution of responsibilities and more. What makes this phase challenging is it’s hard to predict how long it will take or if the path is the right one (e.g. “do we need to keep going, or is this direction a mistake?”)

Transforming Idea – The job of a leader is to help a team work through the chaos phase until they reach clarity. This is challenging as each person might require different coaching, advice, support or training to adopt the new idea. And the team as a whole may need to reform, with different roles and responsibilities. Someone with leadership skills might correctly identify a new direction, but it takes someone with people management skills to help them through the transitions that the new direction demands.

Practice and Integration – Once the new idea is understood and adopted, finally the expected gains can be seen and progress becomes predictable. And eventually stabilizes again as the new status quo.

The model isn’t predictive. It doesn’t tell you how much chaos a particular idea will generate, if any at all. It can’t tell you how long it will take before you find the “transforming idea”. It also can’t tell you whether the new idea you’re introducing is the right or wrong one (e.g. the chaos will never end, or performance will never recover). It’s simply a useful framework for thinking about the psychological patterns likely to arise when something changes.

Inexperienced people often confuse the chaos phase as a failure in their choice. And if they quit early, assuming “chaos” means they made a mistake, and revert back to the old ways of doing things, they likely will never have the confidence to try something that bold again. They now confuse the chaos phase with failure. This is a kind of self inflicted learned helplessness, where the necessary cost to improve and grow is now too psychologically expensive. People and organizations can become paralyzed here, as they’ve become extremely resistant to any threat of a “foreign element”, even though that’s exactly what’s needed to grow.

Some foolish people dismiss Satir’s work based on the question what do families have to do with workplaces or individual adult choices? But workplaces are based on relationships, and we learn our models for how to relate to other people from… our families! Your favorite, and least favorite, coworkers learned many of their patterns of behavior from their early relationship with their parents and siblings. How we define trust, love, collaboration, friendship and teamwork all come from our experience with the first and primary tribe in our lives.

Anuradha Gajanayaka compares the Satir model to Kanter’s Law, which states that “Everything looks like a failure in the middle.” She suggested that we “Recognize the struggle of middles, give it some time, and a successful end could be in sight.“

And that is a key takeaway from the Satir model. Even if you’re doing everything right in your life, or as a leader, when you try to change something be prepared for surprises. Plan time for “chaos” in response to the change, where it’s normal for performance to drop and for experimentation to happen until the new idea is understood, incorporated and refined.

November 21, 2017

How can you know someone’s true motives?

On Tuesdays I write about the top voted question on Ask Berkun (see the lovely archive). This week’s question came from Faisal [22 votes]:

Appearances can be deceptive. How can I, as someone who tends to accept things at face value, develop the habit of searching for true motives of others?

In a practical sense the answer is easy: stop accepting things at face value! You need to ask more questions and think critically about the people you encounter. There are three ways to do this, all listed below.

However at a philosophical level, people are complicated. We often have multiple motives, some of which we might not fully understand when we act. Often we’re conflicted about our desires, regardless of what actions we take. And the reasons that drive our choices in life change over time: we don’t live life with a single consistent unwavering motive for anything. The more intimate the relationship you have with a person, the more complex (and possibly rewarding) it can be to understand their intentions and how your choices impact each other.

That said, here are three ways to try to know why someone does what they do.

1. Ask them

Few people take the time to simply ask direct questions to people they encounter. Somehow it seems rude or confrontational, but if done in a friendly way it can enhance your mutual understanding of each other. To ask something like “thanks for helping me move my things, but I’m curious: why are you helping me?” raises the sophistication of your interaction. Instead of just being a transaction (e.g. buying you a cup of coffee), it now because a personal conversation about intentions and expectations (e.g. how do you relate to me or to people in general? Do you expect something in return? Is this about your own sense of identity?). What they say and how they say it will give you more data to consider about their motives than the actions they take alone.

2. Exercise your judgement

Any new experience can always be compared to past ones that are similiar. You simply need to ask yourself questions like:

What are the possible reasons, positive and negative, why this person is behaving in this way?

What reputation have they earned with me (or with others) in the past that I can put this recent act into context with?

In the past who else do I know that has behaved this way? What did their intentions turn out to be?

If you can make a list of similiar situations, and think through who else you’ve known in your life who you’ve been in them with, you’ll naturally engage your own deeper judgement.

3. Use the judgement of others

You can always ask someone you trust for their opinion. This can be particularly valuable if your trusted friend also knows the person you’re curious about. Simply ask them: “Hey Jane: Rupert keeps buying me coffee every morning. What do you think this means?” Maybe they’ve known Rupert for years as a friendly, generous person, and the gesture is nothing more than that. Or perhaps they share some insight into how Rupert is up for a possible promotion, and is trying to subtly raise people’s awareness of what he does around the office.

In the end we have to decide how much we trust other people and there is no perfectly foolproof way to do that. Sometimes we trust people too much and other times we don’t trust them enough. But if we’re honest with ourselves, we can learn from each oversight, and slowly approach a more accurate way to assess both why the people around us make the choices that they do, and who in our lives is worthy of our deepest trust.

November 15, 2017

The Pay-To-Stress Ratio

On Tuesdays (well, usually) I write about the top voted question on Ask Berkun (see the archive). This week’s question is from Kate N. [via email]: How can I evaluate the true value of a job offer?

I have two job offers: one pays less, but the quality of life (flexible hours, healthy culture) is much better. The other pays far more, and if I can do it for a few years I can be in a much better financial situation. What should I do?

A friend of mine has a job that, on paper, seems great: he’s a high paid business consultant, working for a Fortune 500 company with excellent benefits. But he also has high blood pressure, is overweight and works 12 hour days. Is he paid well? Most of us would say yes, but I’d say his pay to stress ratio is poor.

Pay to Stress is the ratio of the financial compensation compared against the true costs of life quality the job demands. The challenge in computing the ratio is the compensation packages an organization offers are well defined, lets say $150k salary, 20 vacation days and a gym membership. But to compute the stress, and negative impact, on our lives that job will demand requires homework and introspection most people don’t bother to do. The pay is well defined, but what is the true COST on a life for taking this job? It’s up to you to figure that out. For example: perhaps the gym membership is useless because you work too many hours to possibly use it.

In other words: If a job pays you $150k annually, but when you get home each night you are too tired, emotionally and physically, to spend quality time with your friends and family, are you really being paid well?

Pay, in professional circles, is often about status. It’s a symbol of the idea of success. It’s also easy to compare one job to another, or one person to another, in terms of salary, so so we use it as the singular measure of achievement. But this is foolish. The real yardstick of life is time. You can always earn more money, but you can not earn more time. What good is a yacht or a beautiful home if you rarely have the time to truly enjoy them? Many financially wealthy people are time poor, using their wealth to collect trophies they think signify a good life while never actually experiencing one.

Of course stress is subjective. Some people find challenging projects stressful while others enjoy them. In this context what I mean by stress is anything that you need to recover from before you can enjoy the rest of your life. The post work happy hour you need to have at the bar to decompress before heading home indicates a kind of stress took place during the day that you know you need to recover from. Another common symptom of stress are Saturday mornings (or afternoons) you spend sleeping late (trying to) catch up on the missed sleep during the week. Both imply your Pay to Stress ratio is high.

The wise choice is a job that rewards you well both financially but also in freedoms that help you use your time away from work for a high quality life. Those freedoms may include vacation time (which is terribly limited in the U.S. compared to other countries), the ability to work from home, flexible hours (so you can avoid the stupidity of commuting in rush hour) or a culture that measures/rewards your output instead of just your hours. The tech industry has long been a pioneer of many of these freedoms, but they are still rare in most of the working world.

In short, think through the total cost on your life of taking a job when you consider the offer. The potential employer can’t do that for you and likely will use that to their own advantage. If you knowingly take a high stress job that’s fine, especially if you see it as a short term choice to enable you to have better options in the future.

October 31, 2017

Why do people fall into the trap of the narcissist?

On Tuesdays I write about the top voted question on Ask Berkun (see the archive). This week’s question came from J. Mill via email [equivalent to 1 special vote]: Why are so many people charmed by narcissistic people? Which I recast as: Why do so many people fall into the trap of the narcissist?

As the son of a father who was a narcissist, I know this trap all too well. It works like this:

You meet someone and are impressed.

You’re not sure why, but there’s something powerful and deeply familiar you feel from them. Something you’ve always wanted.

As you cross the doorway into their life, you see someone already inside on their way out. As they exit, sad and upset, they warn you not to trust the narcissist.

But you smile in disbelief at what they say.

How could it be true? You ask. The narcissist is so charming. They satisfy something you know you need. So you blame the person leaving for whatever went wrong.

You know you are special – because the narcissist tells you so.

They promise you something you want – something important. Something no one else can offer.

It feels good for a time. But then they forget their promise. You remind them, and they seem to remember.

But then they forget again. Or they lie.

Then you feel abused, but don’t want to believe it.

Maybe they apologize, but not very well. They promise again.

You wonder: have they earned your trust or are you just giving it away? But you think love is trust, so you offer it willingly.

Then you are used again. And again. Each denial makes the next one easier.

Another denial takes less courage than admitting to yourself who they really are and who you are for not seeing it sooner.

By the time you hit bottom and can’t deny anymore, you’re ashamed, wounded and exhausted.

Even when you summon the courage of confrontation, they ignore you. Or blame you for what happened.

So you decide to leave.

As you exit, you tell the next person coming in the door what you learned, but they smile in disbelief at what you say.

You can read The Ghost of My Father, my memoir about my family, for more thoughts on narcissists and how to overcome their influence on your life.

October 24, 2017

Why do so many managers have poor people skills?

On Tuesdays I write about the top voted question on Ask Berkun (see the archive). This week’s question is from Bobby [with 305 votes] is Why do many managers have poor people skills?

Why do so many companies consistently and with depressing regularity keep promoting people to people manager positions when the clearly lack people skills? They are not supposed to do the job, rather get the job done. How can the if they can’t inspire and hold their teams together.

It’s healthy to start by asking how many people in any profession are good at their job? I’m not sure that management is an exception. Perhaps in general we’re not as good as the basic fundamentals in most professions and daily tasks as we assume. Trying to find a good car mechanic, landscaper or or a general contractor (to, say, remodel your kitchen) isn’t easy. Good people are hard to find.

Specific to management, “people skills” includes a wide range of things that are hard to find in one person: emotional intelligence, empathy, communication skills, decision making, role definition, conflict resolution, political acumen and more. It’s a hard job that’s often not rewarded well.

Here are six specific reasons why many managers you experience have poor skills:

It takes a good manager to hire one. If the head of the department doesn’t have good people and leadership skills, odds are low they’ll hire someone who does have them. Either they won’t be able to recognize those skills, or even if they do, they won’t prioritize hiring for them. This means good people skills are often an element of culture: some organizations truly value it and make sacrifices for it, while others do not. If the executive is merely waiting to retire, all kinds of dysfunction and incompetence will go on until they leave.

If good managers are scarce they go where they are rewarded. Better organizations, and better teams in any organization, will have a higher standard for many different aspects of work. It’s wise to scout for which teams are managed well and use your network to find your way into them. The best career move is often to find a better manager, even if it’s not the ideal project or role (they will help you in ways than more than compensate for those sacrifices).

If the only way to get a raise is to manage, people become managers for bad reasons. In most organizations the only promotion that comes with more financial rewards is to start managing people. They’re not doing it simply because they want and like to manage people, they’re doing it purely for mercenary reasons. Smarter organizations recognize this conflict of interest and have at least two promotion paths: one that is independent and centered on individual skill/influence growth, and the other more traditional path of management. The Peter Principle is real, which means if a person ends up in a role they’re not good at it’s often easier politically for their boss to leave them there than to deal with consequences of admitting to and correcting the mistake.

Some bad people managers “manage up” well. Managing up is the skill of influencing superiors. This is an important skill for anyone, but especially for managers. In some cases a bad people manager can succeed well enough in other ways and persuade their superiors that they are doing a wonderful job. Unless their superiors provide a channel for feedback from line level employees (e.g. skip level feedback), a manager is never evaluated in an objective way on what working for them is like. Another signal to senior managers of problems is retention: if employees flee working for a manager at a high rate, that should be a warning sign to any executive who cares about how well people are treated. But if executives don’t care to know, dysfunction can be rampant and stay well hidden behind superficial metrics and KPIs. Most cynically, if executives have a strategy where they don’t want employees to stay with the organization for long, why invest in managing them well?

Some people prefer to be managed differently. In some cases it’s not that managers are bad, it’s that they don’t match the needs of the people they are managing. Some employees want a stable easy-going workplace, while others are ambitious and want a fast pace and high adventure. Some people prefer a hands-off work style where they have high autonomy. Others need regular coaching and mentoring. Of course a truly great manager recognizes these different needs and strives to provide them (even if they require him/her to stretch beyond their own natural management style), but sometimes what is cast as “bad management” is really a mismatch of expectations.

Keep in mind there are some things you can do when working for a bad manager to minimize your suffering. And of course if you are a new manager yourself, this guide can help you to avoid the mistakes listed above.

September 29, 2017

Notes from Seanwes conference 2017

I spoke at the Seanwes conference in Austin,TX this week about the Dance of the Possible. Here are my notes from the other talks I listened to (I was sick for a good part of the event so missed a few presentations. Too much BBQ? Quite possibly).

2. Kevin Rodgers, Copywriting

Three questions to ask:

What is your story?

Who do you serve?

Where is your why?

“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: The hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.” ― Joseph Campbell, The Hero With a Thousand Faces

“Nobody wants to read your shit.” – Steven Pressfield

“TL;DR” – Everyone

Simple version of hero’s journey for writing: Identity, Struggle, Discovery, Result, Call to Action

Examples: Weight Watchers Jessica Simpson ad, Rudolph the red nose reindeer song

Knowledge content is dead – there is a surplus of information and facts for free online. People have to feel something to connect with what you do. If they don’t feel it they won’t feel you.

Rodgers showed a long segment of his stand up-comedy routine, highlight jokes that used the Identity, Struggle, Discovery, Result, Call to Action pattern.

3. Scott Oldford

Missed this one.

4. James Clear, Habits

Aggregation of marginal gains: 1% gains in nearly everything you do. The results of small improvements, over time, is surprisingly and powerfully high.

Good habits make time your ally, bad habits make time your enemy

Four stages of a habit

Noticing – happens because there is a trigger

Wanting – because there is a desire

Doing – happens because there is an ability to acknowledge the results

Liking – happens because there is a reward

Noticing is crucial for breaking bad habits and building new ones. Can’t change what you don’t notice.

Habit scorecard – helps noticing

Goal Write down each habit you perform each day

Then assign a score to each habit: positive, negative or neutral

Does this habit cast a vote for the desired identity I want to have?

Diderot effect: one purchase tends to lead to other purchases.

Habit Stacking: Hunan behavors are often tied to each oter. Habits come in bundles.

Meditation: after I brew morning coffee, I will meditate.

Exercise: after I get home from work I will change into workout clothes

Gratitude: after I sit down to dinner I will say one thing I’m grateful for

Decluttering: after I take my shoes off, I will put one thing left out away.

Financing: Before I make an online purchase, I will calculate how many hours of work it will cost me

Television. Before I turn on the TV I will say the name of the show I want to watch.

Dopamine is not just pleasure it’s also about desire and anticipation. Desire comes before behavior. Pleasure comes after it. It is your expectation that drives behavior. Every behavior that is highly habit forming – drugs, junk food games – is associated with higher levels of dopamine.

Motivation comes in waves. It rises and falls. Often motivation comes at the wrong time. When desire is high, we need to lock in the habit, or at least start it.

Commitment devices

Ask to have half a meal boxed up before you eat

Charge your phone in any room other than your bedroom

Automattic bank deposits

Delte social media applications on your phone (increase friction)

Put a post-it note contract on your door (can’t go to bed, or do pleasurahle thing, until you do X)

Habits do not form based on time, the form by frequency. They form based on rate of acting, or repeating.

Number of reputations required varies by difficulty of goal. Every outcome is somewhere on the spectrum of reputations.

“i begin each day of my life with a ritual: i wake up at 5:30 a.m., put on my workout clothes, my leg warmers, my sweatshirt, and my hat. i walk outside my manhattan home, hail a taxi and tell the driver to take me to the pumping iron gym at 91st street and first avenue, where i work out for two hours. the ritual is not the stretching or the weight training i put my body through each morning at the gym; the ritual is the cab. the moment i tell the driver where to go i have completed the ritual.

it’s a simple act, but doing it the same way each morning habitualizes it – makes it repeatable, easy to do. it reduces the chance that i would skip it or do it differently. it is one more item in my arsenal of routines, and one less thing to think about.” – Twyla Tharp

One tiny habit can be the spark that sets off the sequence of habits you really want.

The two minute rule (David Allen) – downscale your habit until you can get the first two minutes of it to be useful and mindless. Optimize for the starting line, not the finish line.

The best way to build long term habits is with short term feedback.

Your identity emerges out of your habits.

The goal is not read a book, but to become a reader. The goal is not to write a book, but to become a writer.

It’s often wiser to remove the kink in the hose, vs increase the pressure/force you put through the hose (More thoughtfulness, less brute force).

The meta habit of thinking about your habits/result: integrity report – every summer:

What are my core values

How have I been living by those values

Where have I failed to live by those values

Reflecting on this once a year pulls you back to integrity. Annual review every winter, focused .

Ivy Lee Method – 6 todo items per day, reorder in priority. When you come in tomorrow you only get to work top down until it’s finished. You can repeat each day.

5. Mojca Mars

Why aren’t you using Facebook ads? Common answers: complicated, time-consuming, and expensive.

Most ad campaigns fail because:

Selling to cold audience directly

Wanting to close the deal too quickly

Optimizing for the wrong metrics

Things to do:

Facebook ad pixel

Simple funnel: Attract visitors, generate leads, close sales

wwwh: why, what, who and how

Attract

Make first connection through value, build trust , Facebook pixel tag

what: valuable blog posts & video content

who: cold audiences – interest targeting (or target competitors), lookalike audiences

how: powerful headline (clear problem, questions and cta), branded design. Long format copy currently works well if you earn attention with first sentence.

Lead generation: first transaction with potential customer, qualifying audience

what: free ebook, cheat sheet, checklist, email court, free trial

who: retargeted audience, blog post readers, top web page visitors, contact page visitors

how: reiterate pain (remind them of the pain and offer sweet solution), specific outcome, clear & strong CTA (tell them the one next step they should take)

?? (she spoke really fast so I got lost on the structure of her talk several times)

why: profit, scale your business

what: tripwire product, productize service

who: retargeting (avoid cold audiences), existing leads, pricing page visitors, sales page visitors

how to promote paid product/service: Creative: focus on specific buyer persona, communicate specific value proposition, Social proof & Testimonials

Close sales

Facebook is trying to compete with youtube and vimeo, so they are promoting video content more than any other.

Stranger->value->Prospect->Lead Management->Lead->Sale->Customer

September 18, 2017

Notes from Business of Software Conference 2017

I speak tomorrow at the Business of Software conference. Here are my notes from the sessions so far.

1. Jason Cohen : Healthy, wealthy and wise

“This is not a presentation, a sermon” – a passage from the book of hackernews. “I don’t want to be a founder anymore – there’s a lot to lose from speaking how I feel. We’re profitable, growing, debt free and about to be acquired. The problem is I am supremely unhappy”

The founder who posted this had four choices:

Quit, killing company

Hate the next 2-5 years

Fix it

Keep running the company

It seems to be a common pattern that founders aren’t happy despite achieving all the things they set out to do (See Credit-Suisse research study).

You have to decide to face some ugly , emotional truths – no one will force you to since you have no boss. It’s easy to be a victim of your own denial.

Jason asked the room “who here has taken too long to fire someone?” and most people raised there hands. “Too soon” – on ly a few people. There’s the good reason, and then there’s the real reason we do (or don’t do) thing.

2×2: matrix, Things that don’t need to be done, needs to be done, want to do, don’t want to do

The fact that a thought won’t go away, and keeps you up at night, is a good indicator it’s something you need to deal with.The emotionally tough choice is usually the right choice.

How to do the tough thing:

Be swift: delay never helps, often hurts

Be decisive: flapping hurts

Be kind: to the person, to others, to yourself

Someone is always the smartest people in the room, but many people might believe that it’s them.

A players hire A. B’s hire Cs.. The presumption is that as an A, you are an A at everything, but when you take on a new role, like finance, even after a couple of months you are not really an A. And when you hire, you are calibrating against yourself, so you unintentionally hire a C and staff new roles or departments with C.

“We don’t hire smart people to tell them what to do. We hire smart people so they can tell us what to do.”

Be an editor, not a writer. Hold people to hire standards, but hire people who can do their own job/role better than you can.

Action oriented vs. results oriented – results are about outcomes and customer satisfaction, action is just a series of acts and choices

He told the story of selling his first company Smart bear. He got an offer and talked to his wife, who said “you have to sell.” And he asked why. And she said “Don’t you know how unhappy you are?” And even when he sold the business, he thought he’d feel better, but not at first. It took a long time to resort himself.