Scott Berkun's Blog, page 4

June 8, 2020

Design hero: Chuck Harrison

[Originally this was a twitter thread – reposted here with various edits and link corrections]

A new hero for me is Chuck Harrison, one of the first black designers, and executives (1961), in American corporate history. He spent much of his career at Sears, and designed 100s of well known objects, some of which you probably know. He redesigned the View-master from a bland, clumsy device, to become something kids and adults loved to hold and use.

He developed the idea to make garbage cans out of plastic (much quieter than metal when the garbagemen emptied them at 5am), and make them stackable so they’re easy to ship and store.

To convince people his design was better, he devised a test. “we froze the can at -40 degrees for days, put a 50lb bag of sand in it, and threw it off a 5 story building.” It didn’t break – It bounced! Marketing replicated this in their advertising – but from a helicopter.

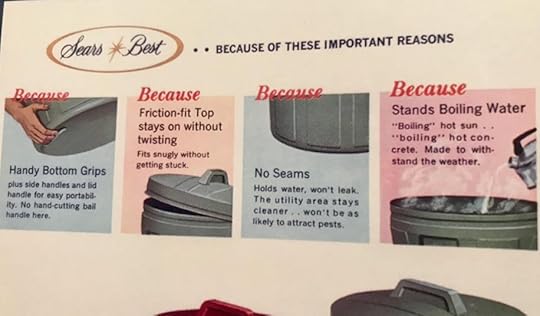

He thought carefully about user experience and affordances – “easy for the owner to remove [the lid] but hard for dogs or raccoons” – plus a sloped lid for rain runoff and hand grips at the bottom. Ideas used in Sears’ advertising.

He grew up in Arizona in the 1940s, which he says “may have been more racist Mississippi” – and poverty was an issue too – his high school basketball team was so poor they didn’t have uniforms – his coach wrote player numbers on t-shirts.

He struggled entering college because of dyslexia. He studied econ. until a councilor suggested art. His grades improved & he considered interior/industrial design. He was told “he’d be a good painter” but quipped “if I told my father that he’d make me paint the garage.”

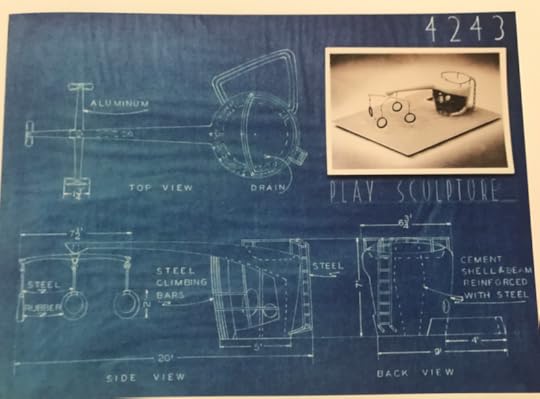

He went to @SAIC_Design (Art Institute of Chicago) as the only black student. “…in the arts, racism seemed less intense… sharing information didn’t represent power so classmates were helpful” He learned from supportive professional designers too. Here are some sketches for one of his student projects, a design for a playground.

He served in the army, learning cartography/mapmaking and photography. After two years he reached out to his professors about graduate school, but they didn’t have a program – they created one for him.

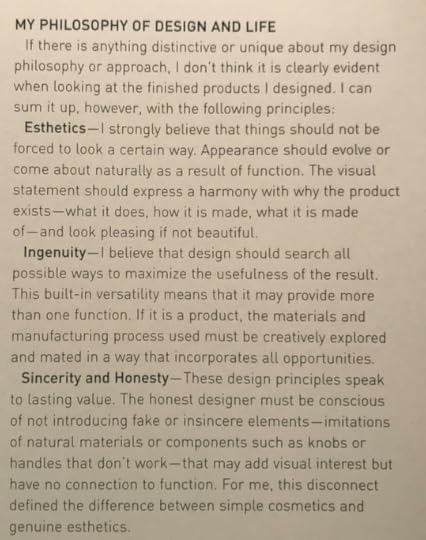

Henry Glass (professor) helped him early in his career. “Henry was a godsend… someone looking over my shoulder… I learned it wasn’t only expressing a concept, but how to successfully get it to the marketplace” – This holistic design view would be a hallmark of his work. Much like Dieter Ram’s 10 principles, Harrison had a clear and honest philosophy about how things should be designed.

Many of these quotes and photos are from Harrison’s own memoir and portfolio – A Life’s Design (which I recommend – he writes well). There’s also a thoughtful obituary from the NYTimes about his life and work. #designmtw #design #inspiration

“If I were to share one thought with the #design community of today and tomorrow it would be to remember that your purpose your gift to the world is to provide straightforward solutions to real problems for living, breathing human beings.” – Charles Harrison

June 3, 2020

Police Reform and Systems Design in 5 Clear Points

Patrisse Cullors, co-founder of Black Lives Matter, has said that police culture has long been detached from the needs of the communities they are supposed to serve and that it needs to be transformed. Police racism and abuse of power are well documented, but why have so many attempts at reform failed? At one obvious level if the culture in an organization is still unchanged, what should we expect? But yet many of the tactics that have been tried address only symptoms and are often subverted as changing a policy does not change culture.

Charles P. Wilson, Chairman of the National Association of Black Law Enforcement Officers, has even stated, “The [police] system was designed to keep poor people under control” reflecting how even today the disturbing roots of policing in America (slave patrols in the south, protecting the wealthy, warrior vs. guardian culture) retain their influence.

That word, system, is one that designers know well. It means rather than being able to address a problem as a singular thing, there are instead multiple forces that interact, often in ways that are more complex than they seem. Just because a problem is easy to spot, doesn’t mean it’s easy to fix. Systems theory is its own subject, as are police history and police reform, but I haven’t seen them brought together in a simple way that most people can grasp.

Shaila Dewan, who covers criminal justice for The NY Times, explored this in her rundown on The Daily podcast of 5 of the systemic reasons (there are more) for why the police stay protected even when they violate our trust. She explained:

“Our systems are set up to protect police officers from repercussions… its even been bitterly complained about by police chiefs coming in wanting to change their departments… Minneapolis had two police chiefs who were heralded as reformers. The current chief sued the department for racist hiring practices before he became chief… but he may be forced to rehire [the four officers involved in the George floyd killing] “

This view helps explain the Gordian Knot of how police, unions and other organizations, resist change and protect each other. It’s far from complete, but it offers an introduction into why this has been a hard problem to solve.

Dewan’s five systems are listed here – I’ve modified them slightly and added my own notes (you can hear her explain them on the podcast):

The police police the police. It’s commonly known that most departments have Internal Affairs divisions that investigate police issues (often romanticized heroically in movies), but we forget that they often report into the same larger organization that ultimately manages the people being investigated and who have incentive to bury or minimize bad news about their department. Internal affairs typically only investigates and makes recommendations, via methods that are often kept from the public. They are usually former police officers who are part of the same culture and community as those they are investigating. As citizens we call the police as a (hopefully) objective actor but the police are not policed in the same way. Police records about individual officers, complaints and discipline history, are often hard to obtain and provide limited information to the public.

Courts and arbitration protect police officers. Public employees can appeal firings or suspensions to an independent group or mediator outside of the police department. Through these appeals police are often given lighter sentences or are reinstated, since they often base judgements on past precedent of leniency (which self-reinforces light penalties). The Twin Cities Pioneer Press analysis showed fired cops were reinstated 46% of the time.

Civilian review boards rarely have power. Review boards are often created in response to police brutality, but they are often toothless, relying on journalists and the media to apply pressure. They are granted meetings with police leaders to discuss issues or review cases but not much more. Often few complaints brought to these boards result in any action.

Police unions are very powerful. Unions represent the needs of officers, not the needs of the police department or society. They are well funded compared to other unions (given the political nature of policing) giving them significant negotiating power with city governments. A primary duty of unions is to protect police jobs. “They are often the biggest opponent of reform minded chiefs. Minneapolis is a textbook example of this.” Minneapolis Police Union President Bob Krul, whose own words on violence are disturbing, has 29 complaints against him as an officer. He has stated he will get the jobs back for the officers involved in the George Floyd killing.

Reasonable Fear laws reduce sentences. Prosecutors and juries, who depending on their ethnicity and neighborhood have had far different experiences with the police, are often willing to give officers the benefit of the doubt in use of force since they are viewed as public servants, taking risks for the greater good. The concept of reasonable fear laws is that officers have dangerous jobs with split second decisions: If an officer can make the argument that a reasonable officer would have been afraid for their life in that situation, than a jury or prosecutor is not supposed to convict or judge harshly.

In systems theory stasis is the tendency for systems to be resilient to change. Each part of a functioning (in the sense it achieves outcomes the people in it desire) system will naturally adapt to keep the system stable and even compensate for changes, neutralizing them.

This helps explain the pattern of:

Something terrible happens

Society is outraged

Change is demanded

A new policy is created (or a police chief who believes in reform is hired)

And… nothing changes

Dewan offers that “.. even an institution that wants to change itself can’t overcome it’s architecture.” There are often just too many powerful or slow moving forces that work against change happening. We don’t often talk about the value of institutions, but they are meant to provide value across generations. When designed and maintained well, the slow moving nature of an institution is an asset, not a liability. It’s a different scale of investment and return that many have forgotten.

Fixing a broken system usually requires:

Studying similar systems and why change failed or succeeded

Integrating different kinds of expertise

Considering both symptoms and causes

Attacking the problem from multiple directions

Growing and nurturing a new culture with it’s own stasis/resilience

Understanding feedback loops & how parts of the system influence each other often in complex ways

Committing to the long term, possibly over generations, as change may require more than a single term for mayors, politicians or anyone involved, just to even successfully manage out the defenders of the status quo.

References / Related:

The System That Protects Police, The Daily Podcast

History of Police Reform in The U.S.

The Marshall Project’s Book Recommendation List

Reasonable Fear Laws

Police Reform and the Dismantling of Legal Estrangement

Thinking In Systems: A Primer

Why Do We Accept Bad Systems?

Should you Cheat or Fix a Broken System?

Can You Have a Career In Solving Big World Problems?

May 13, 2020

Want me to make a virtual book tour visit at your organization?

Does your team need a morale boost? Something to inspire their creativity and recharge in these unusual times?

The stories and ideas from How Design Makes The World can inspire your staff, let them laugh and learn, all while discovering new ways to think about their work that they can bring into the rest of their day.

I’m available for remote talks for your entire team or organization. If you’re interested in How Design Makes The World, setting this up is easy:

All you need to do is purchase 30 or more copies of How Design Makes The World for your team (you can buy bulk kindle editions, or print through Amazon, Bookshop or Porchlight)

If you want signed copies (print, obviously!), and/or a custom header page in each book (with your organizations logo and a custom message), this can be arranged for a fee + shipping costs.

Contact me to schedule a day/time that works best.

I’ll do a presentation of key stories and the big ideas from the book, followed by an extended Q&A with you and your team.

Not sure? Here’s a short film that might help get you inspired.

May 5, 2020

Available now: How Design Makes The World (+trailer)

The day is here. You can now buy How Design Makes The World in various formats and from all the usual stores.

You can buy the book:

On Amazon

On Amazon Kindle

Apple Books

Bookshop

You can read sample chapters or hear my quick rundown on who the book is for and what it’s about.

We also made a short film about everyday bad designs, that also celebrates all the good designers who often don’t get the recognition they deserve.

Early reviews include:

“Nobody’s better at explaining how the world really works than Scott Berkun.”

—Jeffrey Zeldman, web design legend and cofounder of A List Apart

“What makes a Jacuzzi better than a Segway? Why do street grids work in some cities, but maybe not in yours? What’s wrong with calling an interface ‘intuitive’? This fascinating book will help you see design everywhere and question why it works–or why it fails.”

—Ellen Lupton, curator of contemporary design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

“An invaluable, essential resource that demystifies and democratizes design for everyone who lives with it–which is to say, all of us.”

—Khoi Vinh, principal designer at Adobe and former design director of the New York Times

“Scott Berkun captures the essence of what makes design so incredibly important in our lives. He frames how we should think about design in a fun and accessible way. How Design Makes the World explains why our world is the way it is, and lays out the questions we need to ask to make it better.”

—Jared Spool, founder of User Interface Engineering

“Everyone in the tech world knows that they need design, but few understand what it is and how it will help them succeed. Scott Berkun illuminates both the problem and the solution. A brilliant book.”

—Alan Cooper, design pioneer and author of About Face

You can buy the book at:

Amazon

Amazon Kindle

Apple Books

Bookshop

April 30, 2020

(video) 5 minutes to explain How Design Makes the World

Yesterday I’d planned to do a livestream about ideas from the new book, but Twitter/Periscope refused to allow it (Vague “Initializing stream…” message never managed to finish it’s job).

Instead… I improvised this short explainer video. Which was surprisingly fun to do. Did you like this? Hit the like button or leave me a comment here and I’ll do more of these.

Who is the book for? Why did I write it? Why should you care? It’s all answered here.

April 29, 2020

LIST: 60+ well designed everyday things that go unnoticed

With the new book coming out, I’m running a little contest on Twitter. Best three answers get a signed copy of How Design Makes The World.

[UPDATE: Winners were already chosen. I chose: the key, the alphabet and the mirror. But feel free to add more you think are worthy to the comments to the list in comments.]

The question: what well designed common object goes unnoticed because it works so well?

Contest closes at 11:30am PST Wed. April 29th. I’ll announce the winners live on Twitter at 12pm.

Leave your entry in the comments or on Twitter. Even if you miss the deadline I’d still love to hear what comes to mind for you.

Here’s the list so far:

The simple toaster oven

Japanese nail clipper

The pencil

The clockface

Yellow dotted line in middle of roads

On road reflectors / Cat’s eye

Bathroom entrances without doors

Mythical bathroom where you don’t touch anything?

Aglets (tips of shoelaces)

Scotch Tape roll holder

Paper Clip

Phillips screw and screwdriver

Cigarette Boxes

Chapstick

Running water

Safety Pin

Hinges

Alphabet

Light switches

Corkscrew

Book

Peeler

Concrete

Toilet Paper

Bidet

Spoon

Stairs

The Metric system

Glass

Handicapped symbols

Chopsticks

Mirrors

Keys / Lock & Key

Hammer

Clothes buttons

Bicycle

Tire pressure valves

Toothpick

Mattress

Glasses

Scarf

Single level mixer (a faucet that controls both temp and water pressure)

Escalator

Waste disposal / recycling

Elevators

Safety Matches

Dog door

Differential gears

Traffic signs

Curb cuts

The dial

The smell added to natural gas

Windshield wippers

Soda can tabs

A mug

Ballpoint pen

Light bulb

Decimal number system

Zipper

Cardboard

Have an interesting one I should consider? Leave a comment.

CONTEST: What well designed common thing goes unnoticed?

With the new book coming out soon, I’m running a little contest on Twitter. Best three answers get a signed copy of How Design Makes The World.

The question: what well designed common object goes unnoticed because it works so well?

Contest closes at 11:30am PST Wed. April 29th. I’ll announce the winners live on Twitter at 12pm.

Leave your entry in the comments or on Twitter. Even if you miss the deadline I’d still love to hear what comes to mind for you.

Here’s the list so far:

The simple toaster oven

Japanese nail clipper

The pencil

The clockface

Yellow dotted line in middle of roads

On road reflectors / Cat’s eye

Bathroom entrances without doors

Mythical bathroom where you don’t touch anything?

Aglets (tips of shoelaces)

Scotch Tape roll holder

Paper Clip

Phillips screw and screwdriver

Cigarette Boxes

Chapstick

Running water

Safety Pin

Hinges

Alphabet

Light switches

Corkscrew

Book

Peeler

Concrete

Toilet Paper

Bidet

Spoon

Stairs

The Metric system

Glass

Handicapped symbols

Chopsticks

Mirrors

Keys / Lock & Key

Hammer

Clothes buttons

Bicycle

Tire pressure valves

Toothpick

Mattress

Glasses

Scarf

Single level mixer (a faucet that controls both temp and water pressure)

Escalator

Waste disposal / recycling

Elevators

Safety Matches

Dog door

Differential gears

Traffic signs

Curb cuts

The dial

The smell added to natural gas

Windshield wippers

Soda can tabs

A mug

Ballpoint pen

Light bulb

Decimal number system

Zipper

Have an interesting one I should consider? Leave a comment.

April 25, 2020

Free Chapters from How Design Makes The World

You can now read the first three chapters from my upcoming book, which launches on May 5th.

The opening story explains how bad design was a primary cause of the Notre Dame fire that nearly destroyed the entire cathedral last year.

Click here or click on the cover to download the PDF.

April 19, 2020

It’s Time To Learn

Yesterday my feed had many references to a new Marc Andressen essay titled It’s Time to Build. I understand it’s popularity as it has an enthusiasm that’s in short supply in the tech world today.

But what he has to say floats about the fray in a disturbing way – thousands of people are dying from a problem we aren’t sure we know how to solve. Unemployment is rising towards 20%, which means basic needs for many is now a struggle. The government decisions happening now will determine how many more thousands of people die, especially front line workers and the poor. And his essay doesn’t give consideration to them at all: having everyone build now will solve everything is his empty answer.

There’s much more. Lets dig in:

Every Western institution was unprepared for the coronavirus pandemic, despite many prior warnings. This monumental failure of institutional effectiveness will reverberate for the rest of the decade, but it’s not too early to ask why, and what we need to do about it.

This sounds compelling at first as I hoped he’d explore what the rest of the world did right, so we can learn from them, but that is nowhere to be found in this essay, despite how well documented our lessons are. What did they do right? Is not a question he seems to have studied. A sign of things to come, or more precisely not to come.

Many of us would like to pin the cause on one political party or another, on one government or another. But the harsh reality is that it all failed — no Western country, or state, or city was prepared

Here he has made pandemic response binary, either you pass or you fail, which is not how things happen in the world. There’s always a spectrum for how to evaluate outcomes. If he wanted to write about the future he could have, but he starts in the present and makes everyone equal as a way out, which dodges learning anything from what’s happened.

Some U.S. States and European nations responded much better than others, as evidenced by the countless charts we all study daily. But that spectrum isn’t convenient for what Andreessen really wants to say, so he frames the world as pass or fail so he can confidently say that everyone (except for all of Asia which he won’t talk about) has failed.

And pinning the blame means you blame someone who was not involved (which he calls here pinning the cause). You can’t say this about someone whose job is precisely to prevent a thing that ends up happening.

For example, if a CEO calls the threat of a competitor a hoax and tells his staff to ignore it, despite their knowledge and interest in doing something pre-emptive, and then that competitor devastates them a few weeks later, and the stock price tanks, and 20% of staff are fired, it wouldn’t be pinning the blame. Instead it’d be holding the people in power accountable for the consequences of their actions.

Andreessen is avoiding politics by not mentioning Trump, or his staff, or any government agency, all of whom are accountable in degrees for what has happened. Andreesen wants to avoid alienating anyone but he’s doing it at the expense of credibility. Later on he writes:

“We need to demand more of our political leaders…”

But he does the opposite in this essay. We pay our leaders to plan for, respond to and be accountable for the outcomes of major events and he gives them a free pass, without even a mention of who has served their citizens well.

We see this today with the things we urgently need but don’t have. We don’t have enough coronavirus tests, or test materials — including, amazingly, cotton swabs and common reagents. We don’t have enough ventilators, negative pressure rooms, and ICU beds.

A cursory look at the successful pandemic responses showed that if you act early and shut social interaction down quickly, you never need vast quantities of ventilators or ICU beds. I’m not saying we should copy what they all did, as there were many tradeoffs, but we should start by learning from it, instead of leaving it out completely from essays on the subject.

Even if prevention wasn’t possible, we could have had the supplies we needed. They were for sale. But someone has to decide it is worth keeping massive expensive inventories that are rarely used. A hospital owned by a corporation that wants to stay lean to keep profits high, is unlikely to do this. What corporations call inefficiency, in the short term, is often very important in the long.

In the movie Catch-22 a corporation replaces parachutes of active WWII war planes with shares of stock, using the logic “when was the last time you actually used one? Wouldn’t you rather grow wealth instead?” Which works great until your plane is going down, which planes at war, at nations in pandemics, often do.

It’s governments that historically are well suited to insure societies against uncommon but devastating events, like wars, famines and natural disasters. Without shareholders and profit motive they can prioritize differently. America’s prized $748 billion military mostly stockpiles missiles, guns and aircraft that will never be used for their purpose, but we pay anyway. Why? In case we need it. That’s what a government can do. Why the same logic isn’t used when it’s about the health of citizens is a better line of inquiry than simply pointing out that we didn’t have enough of something. A small percent of that military budget might have been enough.

This was not a building problem. It was a priorities problem. A logistical problem. A leadership problem. You could call it many different kinds of problems but building isn’t high on the list.

Making masks and transferring money are not hard. We could have these things but we chose not to — specifically we chose not to have the mechanisms, the factories, the systems to make these things. We chose not to *build*

Finally we really get to what he wanted to say all along: BUILD!

But he’s off the rails already. Sure making masks that sit in a wearhouse and transferring money to individual consumers are easy. But that’s not the task at hand. The task was/is:

How to pay for a stockpile of masks/resources that are unlikely to be used for decades

How to quickly distribute masks/resources across 50 states, or between dozens of counties within states, and through various agencies who may not have co-ordinated before (or pay for the training and exercises to make sure they are always ready)

How to build a public tech money transfer infrastructure within existing legacy (.e.g. COBOL) systems that can service citizens during a national crisis

These are hard problems to solve, or in his language, hard solutions to build. He doesn’t frame the problem this way because… I don’t know why.

Maybe because it doesn’t support what he really wants to say? Or maybe he has little experience with massive government infrastructure problems with 30 year old COBOL codebases and didn’t talk to anyone who does, like the folks at 18F or USDS who are technologists who work in the U.S. government and can explain exactly why these challenges are far harder than they appear.

I agree with him that these should be solvable problems but part of the answer is having more of our best young technologists choose to work to help society in profoundly important ways instead of being recruited to join one of Andreseen’s startups that’s going to go try, but likely fail, to disrupt something or other that everyone involved admits isn’t really that important but happens to have a bigger “growth opportunity.”

You don’t just see this smug complacency, this satisfaction with the status quo and the unwillingness to build, in the pandemic, or in healthcare generally. You see it throughout Western life, and specifically throughout American life.

Who has smug complacency? I do not know who he is talking about.

If anything, most of America is angry, scared, lost or grieving, and feels let down in one way or another, which is neither smug nor complacent.

Is he including the people who work at his startups, or use their products? Or the millions of people who use the products his startups are busy competing with to convert into their own customers? Who is he rallying against here? I don’t know and he doesn’t say.

We have top-end universities, yes, but with the capacity to teach only a microscopic percentage of the 4 million new 18 year olds in the U.S. each year, or the 120 million new 18 year olds in the world each year. Why not educate every 18 year old? Isn’t that the most important thing we can possibly do?

What year is he writing this in? Schools and universities are closed indefinitely right now and some are likely to go bankrupt.

I actually agree that education in America is in a bad place but we’re in a crisis. And even if we weren’t this isn’t a problem of building. It’s a problem of leadership, policy and bureaucracy. I don’t think Anderssen has watched season 4 of the Wire. If he had, he’d understand how school quality is inextricably linked to city and state politics. It’s a really hard and long term problem that is rarely solved by budgets and technology alone.

You see it in transportation. Where are the supersonic aircraft? Where are the millions of delivery drones? Where are the high speed trains, the soaring monorails, the hyperloops, and yes, the flying cars?

We are now fully in bad example territory.

Supersonic aircraft? The Concorde was expensive. And noisy. And is convenience of faster air travel really important for the forseable future?

High speed trains? Much of the world has them, but America has not invested much in infrastructure in 50 years. Our highways are bridges are literally falling apart. And our culture has a huge preference for cars over public transportation. In a democracy that makes it pretty hard. Like masks, high speed trains they exist, but someone has to decide to pay for them and we haven’t.

Soaring Monorails? I live in Seattle. I know about monorails. They are inefficient and expensive. (They also don’t soar – birds do. Maybe he meant speeding monorals?) There isn’t one non-imaginary city that uses them effectively (and DisneyWorld doesn’t count).

Hyperloop? Is he only going to mention technological ideas that most experts think are ridiculous for very clear reasons but the uninitiated love to romanticize?

Flying cars? Yes! He did it! Had he mentioned jetpacks too he would have had the full set.

Had he simply listed important problems that he feels we have underinvested in (education, infrastructure, emergency response, climate change) I’d be fully behind him. But that’s not what this is. It’s an underthought list of tech-lust thinking. He was trying to be inspiring here but these are terrible examples.

How about free internet for all? (A timely problem since underprivileged kids can’t do schoolwork from home right now). How about ensuring basic health care for everyone or even that every family has enough food to eat for the next few months? Those are building problems too, but they don’t sound as cool to the tech-centric as his list does. Historically the truly important things technology can do for us in the long term don’t seem cool, but maybe a silver lining of the pandemic is that will change.

Building isn’t easy, or we’d already be doing all this. We need to demand more of our political leaders, of our CEOs, our entrepreneurs, our investors. We need to demand more of our culture, of our society. And we need to demand more from one another. We’re all necessary, and we can all contribute, to building.

I’m doing my part my demanding more from his essay. And you can do the same by demanding more of mine.

I’d prefer you also go into the part of your community that is struggling right now and help them get the basics they need. If you go to them (virtually of course) and listen, and pay attention, and learn, I bet you’ll find plenty of easy things to build that will help them right now.

Even better, find people already building solutions, and have been working on these problems for years, who need more money or other support. Builders are often bad at helping if it doesn’t involve them building something themselves (e.g. the mostly pointless pandemic hackathons), even if they’re not the best person to do it.

There is only one way to honor their legacy and to create the future we want for our own children and grandchildren, and that’s to build.

I can agree with this. Provided we’re talking about building societies, safety nets, higher quality of life for communities and the tools they actually need to make that future, I’m in. Or building better tools and telling better stories for reminding us how interconnected our fates are.

But first we have a crisis to solve. And unless you’ve lived through a pandemic before, it’s time to learn before we act. We have to look to our experts who know the options and the tradeoffs and how they played out in the past. And more than anything, resist the temptation to jump ahead and likely repeat the mistakes that have been made before.

March 31, 2020

Want a better world, by design? Join the street team

Want to read my upcoming book, How Design Makes The World, before everyone else?

And/or are you passionate about good design, of products, of cities, of societies, and want more people to understand it, care about it and fight for it? Especially with all that’s happening now?

Then I need you! You are a great candidate for this street team.

A street team is a small group of people passionate about a book, or a topic, who are willing to volunteer a little time in return for early access.

You probably already talk to your coworkers and friends about why they should care more about good design or a well-designed world (or wish you were better at it). This book was designed to be a natural ally and asset for you.

What you get if you join:

a free pre-release copy of the book

images, quotes, excerpts and other easy to share material

weekly goals so we can work together as a team

a fun and good project to root for

Training on how to persuade people to care about design

rewards like signed book copies and free coaching sessions for most active folks

Direct access to me as I’m on the team too!

What you do:

Write a review on Amazon / GoodReads

Share images and quotes to your network, on Facebook, Twitter or other media

Recommend the book to influential people you know

Teach people why good design is important (the book makes this easy)

Interested? All you have to do is go here and answer a few questions. Thank you.