Scott Berkun's Blog, page 9

September 8, 2017

Notes from Mind The Product 2017

I speak later today at Mind The Product, an event about product management and design, in London. Here are my notes from the sessions so far.

1. Martin Erikson

Product management is about people. You can only build products people love as a team. Product managers are not the CEO of anything. Regardless of your job title, we are all product people. Perhaps instead of calling ourselves product people, we should call ourselves people people. We can only learn how to do this well by coming together and sharing what works and what doesn’t. Which is why he founded Product tank – the core community behind this conference. 1592 product people from 52 countries are here today. The goal for today is to meet the people who mind the product.

2. Jake Knapp , author of Sprint

(hi-five training – the secret is to watch the elbow, not the hand)

2001 – Jake worked on Encarta (Remember CD-ROMs?). Soon wikipedia launched, which they found interesting but didn’t take as a threat. But by 2003 it had more artiles than Encarta did, and using the web for research, which was always there and always free, even if the quality wasn’t great.

Jake proposed an idea – it took months to prototype, build and ship. And they did. It was a more web-like design for Encarta. But unlike today, you had to go to physical stores to buy software (no-app store). The box design was important – and the logical thing would be to show the new design and the name of the product – but they didn’t. They made the mistake of waiting till the end to involve the marketing team, which went with a generic design. The major redesign work earned a single bulleted list buried on the front. Soon Encarta’s market share declined until the product was killed (if you do a google search for Encarta, the first result is from Wikipedia).

He went to Google in 2006 and recognized they often followed the same broken process. And sometimes with 20% projects the idea would spin out of control and never quite launch. Later on a project called “Google Meeting” and they built a prototype and stating sharing it around the company. In 2011 it launched as google hangouts.

In 2010 he experimented with the idea of design sprints. In 2012 he went to join Google Ventures, which worked with startups. He was curious about how startups managed the ideas and time and discovered it was similar to the same old failed process, with marketing coming in late at the end, too late.

Build-Data-Idea cycle – classic notion of not going too far without validating and adjusting.

The perfect week (the design sprint): get rid of all default habits of scheduling, and follow a system (aim for the elbow). By default, teams are fragmented. But in a sprint everyone is all together in the same room for the entire week.

Monday: Map – focus on one key moment for the customer. You draw a map of the flow of interaction for how the customer will walk through the experience.

Tuesday: Sketch – everyone sketches – you work alone, but together in the same room. Everyone quietly sketches solutions and then gather together to discuss them.

Wednesday: Decide – silent review of sketches, structured discussion of each idea, and the “decider” makes the call

Thursday: Prototype – the work gets divided up and simple tools get used to mock things up and stich them together. With hotspots it’s not hard to create something you could even show to a customer and walkthrough the experience.

Friday: Test – get quick and dirty data with 1:1 interview, with no sales pitch and asking them to think aloud. 5 interviews and the rest of the team takes notes. Observations are put on wall with post-it notes to compare observations.

Next sprint: Repeat and perfect

Some organizations plan to run a sprint at the start of each quarter, and then have enough confidence to push through to building a shipping. Jake has run 150+ design sprints.

He told a story of designing a delivery robot for hotels. One problem was that people had way too high expectations (from movies) of what robots could do. Using a design sprint, they experimented with three ideas: games, faces and dancing. The game idea didn’t work, but a simple face design combined with “dance” (more of a shimmy) was just charming enough without setting people’s expectations too high.

Design sprints allow you to take big risks, and focus on the moments of the experience that matter the most, without costing very much (one week).

3. Blade Kotelly (Advanced Research Lab, Sonos)

Edison didn’t invent the light bulb. It was Joseph Swan. But Edison successfully made it into a product and changed the world.

He asked the audience questions: Is innovation important? (many hands) Is user experience important? (many hands) Does user experience as a competency have a strategic role at your company? (few hands). He implied this was a mistmatch of ambition and reality.

A problem well stated is a problem half-solved. – Charles Kettering

He uses a ten step process in the design thinking course he teaches.

Identify

Gather Information

Stakeholder Analysi

Operational Research

Research

Hazard Analysis

Specification

Creative design

Conceptual design

Verification

Two phases of innovation:

Phase 1: Learning how to think about solving the problem, defining questions to use to help define the problem. “Is this really a problem? Who’s problem is it? What words best describe the problem?” (He calls this experience center-lining)

Phase 2: Standard design process

Apple Newton had the wrong centerline. Processor wasn’t fast enough, it was expensive and too big. The Palm Pilot had the right centerline.

4. Teresa Torres

She worked on a project for college alumni, and by accident they were allowing spam to go out to the mailing lists they had created. They brainstormed and one idea that teammate Seth suggested was to add google maps so alumni could see where they all are. She asked “how does this solve the problem?” – and he said it didn’t, but it was cool and would drive engagement. She asked the rest of the team and they agreed. Teresa was baffled.

We fall in love with our ideas, even if they don’t apply to the situation at hand. We have to remember to ask “is this idea any good”. We tend to consider one idea at a time, when we should be asking “compare and contrast” questions. Good is not an absolute trait, but we often assume that it is. When we consider more ideas we ask better questions.

She realized she didn’t take the time to get the team focused on the real problem at hand. The notion of problem space and solution space have (gratefully) become more popular.

She found value in the book Peak, by Anders Erickson. Which explained that experts have more sophisticated mental representations of reality than novices. Teresa came to the meeting from customer visits and was thinking about their problems. But Seth had just read about Google Maps APIs, so his framework was different.

It’s hard to prioritize a list of unlike items. You need a system or process to ensure you are thinking clearly about the comparisons you make. She described the Opportunity Solution Model, a tree like visual tool for framing problems to aid in critical thinking. If you focus on too many problems you end up with shallow solutions.

Instead of arguing about who’s idea is better, you instead argue about which problem is more important to solve.

She explained how dot voting is a handy technique to use with teams to sort through candidate ideas.

August 10, 2017

Notes from PPP 2017 Chicago

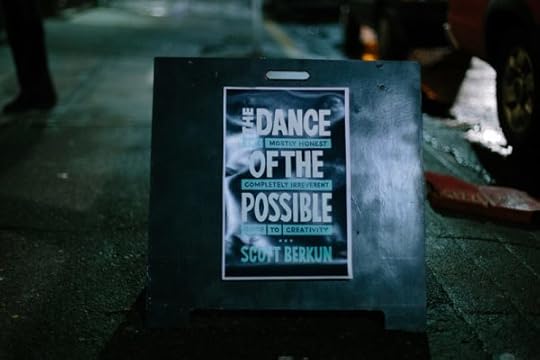

I spoke this morning at Prototypes, Process and Play, in Chicago about The Dance of The possible (slides). Here are my notes from the sessions so far.

2. Making Moonshots, Mathew Milan

Leadership is the reduction of uncertainty n an organization – Paul Pangaro

Reference: The Little Grey Book on Leadership, Paul Pangero

Question: how do you help reduce uncertainty? Perspective, principles and practices. Creating confidence by reducing uncertainty. The challenge is that then average Fortune 500 company lasts 15 years. A company needs to find a way to replace an entire better business while it’s still running.

He used to think CEOs were stupid. They say the same simple stuff over and over again. Now he realizes repetition is everything. “By end of the decade, we are going to put a man on the moon” – Executives have to deal with huge amounts of risk, and repetition and clarity is one way to provide it.

Designers (Engineers) ask: What is possible? How might we do it?

C-level asks: Can we do this, should we do this?

Tesla’s Secret Plan – Great example of a CEO managing risk right.

Build a sports car

Use that to build an affordale car

Use that to build an even more affordable car

While doing above, provide zerio emission power

Don’t tell anyone

General Principles:

Don’t start from scratch

Set high level goals, not detailed path

Break into small steps

Address big risks as early as possible

Prototype your way into production

The risk of deferring risk

You don’t know what you don’t know

You push the unknown into the future

Your exposure to unknown compounds

Test your biggest risks first – often it’s not design risk, it’s technological risk.

RAT: Riskiest assumption test – It’s more important to vet risks first than to explore what’s possibly viable.

Innovation is s search problem – The pivot approach works fine when you are small and fast, in a small startup. But for large organizations you need a portfolio.

3. Carmen Medina, Lead Above Mediocre Thinking

June 22, 2017

Netflix’s updated guide to culture – an analysis & commentary

In 2009 Netflix released a slidedeck outlining their company culture and I summarized its core themes with commentary in a popular post. This week Netflix released the first major update and here’s the rundown.

What changed in 8 years?

The most striking change is that it’s no longer a slidedeck, but an actual document of corporate philosophy. Part of the thrill of their original release was that the format, which was an internal presentation, gave the sense we were seeing something not designed for public consumption and was therefore more authentic.

That allure is gone: they removed the mocking references to Enron’s corporate values or high priced employee sushi lunches. Also gone is the cheesy yin/yang symbol and the generic Arial font (It’s Gotham now). The interesting charts have also been removed. This is now as much a reflection of a mature organization’s wish for how to be perceived as it a tool for attracting talent they think will fit their ideals.

The Good:

Most of the major points I identified from the original are still here.

“Our core philosophy is people over process.” They emphasize in many places how little they care for bureaucracy or the status quo. Tied to this is a demanding philosophy of performance and high expectations.

“The real values of a firm are shown by who gets rewarded or let go.” It’s rare for an organization to talk explicitly about the central value of firing people (See Innovation by firing people). They wisely identify how empty most corporate value statements are, especially when people are allowed to remain in the organization who violate them. (A problem I called out in my critique of Airbnb’s culture document).

Their list of core values is good, but commonplace. As they point out, it’s easy to make lists of values but far harder to find leaders willing to uphold them (“It’s easy to write admirable values; it’s harder to live them”). Their list includes: Judgement, Communication, Curiosity, Innovation, Courage, Passion, Selflessness, Inclusion, Integrity, Impact. A fine list but similiar to ones many companies have.

We are a Team, not a Family. This new clarification was compelling. “A family is about unconditional love, despite your siblings’ unusual behavior. A dream team is about pushing yourself to be the best teammate you can be… and knowing that you may not be on the team forever.” A team is a better metaphor for workplaces in many ways than families are, and too often when executives try to explain their ideas of culture, they use family models (permanent, based on respect, unique) rather than team ones (flexible, based on performance, many can exist). One misstep is Netflix’s odd use of ‘unconditional love’ and ‘sibling’s unusual behavior’. It makes it sound like they have a negative view of families more than it clarifies how they want teams to function. I think they were trying to say that respect on a team is conditional and based on behavior, which they could have said without bringing weird siblings or asides about familial love into it. I’m sure some of their employees have odd habits, as weird as some siblings, and the presumption is they want coworkers to be accepting and supportive.

The No Asshole Rule. They refer to this as “no brilliant jerks” but it’s clearly in line with Bob Sutton’s The No Asshole Rule philosophy. Their justification is simple: ‘on a dream team, there are no brilliant jerks The cost to teamwork is just too high. Our view is that brilliant people are also capable of decent human interactions, and we insist upon that.’

Trust, not rules. It’s always refreshing to read about a place that wants to treat employees as adults. ‘Our policy for travel, entertainment, gifts, and other expenses is 5 words long: “Act in Netflix’s Best Interest.” We also don’t have a clothing policy, but no one has come to work naked; you don’t need policies for everything’.

The Questionable:

In the original I called out several problematic ideas. Most of them are still here, but refined and recast in this new edition.

What is Integrity? Their answer is curiously narrow. ‘In describing integrity we say, “You only say things about fellow employees you say to their face.’” This is more about transparency, where you are forthcoming and don’t hide useful information from people, than about integrity. Integrity is, perhaps, based on practicing what you preach and honoring shared commitments. They do list other attributes for integrity (admit mistakes, treat people with respect) but the emphasis on who you say things too struck me as strange. It could be implied that if you don’t have the moxy to confront someone directly, perhaps about their offensive behavior in meetings, then you then shouldn’t tell your boss, HR, or anyone about it. I don’t think this is what they meant, but their odd emphasis makes it hard to know. They do a better job at completing the idea of integrity in how they describe courage: “You question actions inconsistent with our values.” But even questioning isn’t enough – one assumes they want people who act on their values and insist others do too.

Is the Keeper test a good one? Their philosophy for firing people is based on this question: “if someone on your team was thinking of leaving for another firm, would you try hard to keep them from leaving? Those that do not pass the keeper test are promptly and respectfully given a generous severance package.” But what if the reasons here are the managers fault? Or if they don’t like the employee for personal reasons? Or there is a breakdown in performance feedback? I admire the clarity of this test, but it can’t work on its own. You need a “Manager sanity test” that asks: “why do I feel this way about this employee? Have I told them I feel this way, discussed it and created a plan for improving the situation, before deciding not to keep them? Is there something I’m missing?”

Misunderstanding of great teams. “If you think of a professional soccer team, it is up to the coach to ensure that every player on the field is amazing at their position”. This is a shallow understanding of great teams. A great team has talent, but just as important is that the players work well together. The notion of a dream team fits the all-star fallacy: that simply having the most talented person at every position is enough to make a great team. Many all-star teams are terrible – playing at levels worse than mediocre teams in the same sport. The reason is all-star teams often have little chemistry and too much ego. A wise coach builds a team that is a mixture of both a) the best talent at each position, but also b) with a sense for how the players styles will work together, what roles they can play, and how their strengths and weaknesses balance. Great teams often have role players that are not the best at their position in the world, but fit better with the rest of the team, and the style the coach chooses for how the team will play, than a star would. And since the nature of projects in a fast paced organization like Netflix change often, it’s likely that on some projects an employee will be the star, and on others they’ll play a more supporting role. Both are important roles. It’s a reflection of a strong team culture to acknowledge these forces as healthy, that playing different kinds of roles creates opportunities to learn, rather than simply believing great talent alone makes for great teams.

What do you think of Netflix’s philosophy? What, if anything, would you adopt in your workplace if you could?

Read my full notes on the original 2009 Netflix culture document here.

April 11, 2017

Does “think outside the box” help? Popular creativity cliches explained

While researching my new book The Dance of the Possible, I studied the history of some of the most misleading ideas that have been popularized about creative thinking. Similiar to the Myth of Epiphany and the other creative myths of innovation, these sayings are misleading despite their popularity.

1. Think outside the box: this famous saying has the illusion of being helpful, but it’s mostly useless. The implication is that you should challenge assumptions and test constraints, but anyone who says this phrase is betraying their own advice. If they were helping to solve the problem at hand they’d offer a specific idea, or solution, that qualified as “out of the box” thinking, rather than simply saying the phrase and demanding that someone else do it.

The phrase comes from the 9-dot puzzle that was used in a research study conducted by J.P. Guilford in the 1970s. The trick to the puzzle is to ignore a common, but unstated, constraint that puzzles like this usually have. The implication is that we invent false constraints all the time: and this is the one nugget of usefulness in the whole puzzle story. Challenging constraints is one approach to problem solving.

However it turns out that being told to think outside the box doesn’t actually help much. Recently different researchers replicated the Guilford study, but gave one group the advice to, more or less, ‘think outside the box’ . The result? It didn’t significantly change the results. This shouldn’t be a surprise. Simply telling someone to do something hard doesn’t make it any easier. Our brains like to be efficient and assuming rules and constraints is what our brains are largely designed to do (some optical illusions demonstrate this well).

More broadly, logic puzzles like the 9-dot example rarely teach us very much. They often depend on a single trick or hidden assumption, which is a poor representation of the skills of problem solving and idea generation required to develop ideas in the real world. It’s far more useful as a leader to demonstrate good thinking, or create a healthy environment where interesting ideas are explored, than simply to demand other people engage in something simply because you say a phrase or post a sign.

2. Left brain / Right brain. Dan Pink unfortunately popularized this notion in his popular, but problematic, book A Whole New Mind – despite the left/right brain notion being mostly a misunderstanding of science. It is true that we do have two hemispheres in our brains, but the way they interact is complex and many areas on both sides contribute to what we describe as creativity.

The left/right brain concept goes back many years, but it was neuroscientist Michael S. Gazzaniga’s research in the 1960s that demonstrated how there are different functional centers in the brain. He did tests where one part of the brain, in a patient with a head injury, clearly didn’t understand or know what the other part of the brain was doing. But the conclusion was not one of dominance – “you can’t be right brained any more than you can be right lunged or right kidneyed”.

People love easy, binary models for things and take pride in basing our primitive notions on the pretense of science. This is why people still say “he’s left brained” or “I’m a right brained person” despite how misguided those labels are. The Myers-Briggs test has similiar problems of being popular for how it satisfies our emotional needs to identify ourselves, more than anything to do with science or how personalities work.

Of course it is fair to label our personalities, as some people are more logical or free spirited than others, but it’s a mistake to confuse this with anything structural about how our brains work. As Jeffrey Anderson, a brain researcher, said: “It is certainly the case that some people have more methodical, logical cognitive styles, and others more uninhibited, spontaneous styles… this has nothing to do on any level with the different functions of the [brain’s] left and right hemisphere.”

3. Blue sky (constraint free) thinking. This phrase, most often used in product design and marketing, is a request to eliminate all constraints, and to work on a project free of any restrictions. The problem is that the benefits of working on a blue-sky project are often, but not always, more romance than reality. Constraints are very useful in finding new ideas. The request to ‘think blue sky’ can often lead people into the trap of ignoring seemingly smaller, or simpler ideas, that, if explored, could lead to the best solutions.

It can certainly be fun to think about solving bigger or more open problems. Imagining what you’d do with a 500% larger budget or an extra month of project schedule might yield an insight that transfers back to the actual constraints. But the desire to work ‘blue sky’ reflects a misunderstanding of how constraints often help, rather than hinder, the creative process.

A constraint, which can initially seem frustrating, is an important kind of information. It gives you something to start with, and work against in generating and testing ideas (and some research support this). For example, it’s much easier to write a poem that rhymes, than to write one in free verse.The structure of a rhyme provides information to work with and a structure, or shape, to try putting ideas into. Dr. Seuss famously wrote The Cat in The Hat based on a constraint from the publisher to use less than 250 different words.

There are many different kinds of constraints, and the way the constraint is defined can change how useful or not it is in solving a problem. Often it’s defining the problem thoughtfully, and working to examine and study the nuances of its constraints, that is where the real big insights are found. This is especially true when working on projects where you are designing something for other people.

Of course having too many constraints, or ones that conflict with each other, can render a problem unsolvable. Sometimes people are asked to do 1st rate work on a 3rd rate budget and it’d be unfair to tell them that if they were creative enough they could succeed.

What are some other popular, but misguided, bits of creative advice you’ve heard? Leave a comment and I’ll investigate (Thanks to the folks on twitter who suggested some of the above)

March 31, 2017

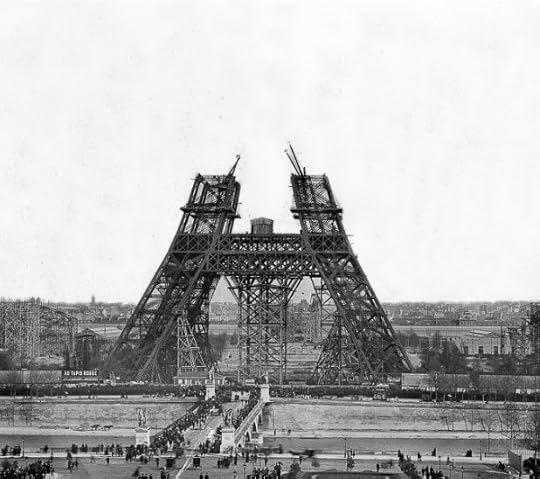

What We Can Learn From The Eiffel Tower

[In 0 21 days my latest book, The Dance of the Possible: the mostly honest completely irreverent guide to creativity, launches. I’ll be counting down the days until then with the story of an interesting idea, fact or story related to the book – you can see the series here – note added 2/22/17]

We take great works for granted. We forget, but the fate of even our most famous ideas and creations was far from certain at the time they were proposed. A powerful exercise anyone can do is to pick a famous creation and go back in history to the days before it was made. Only then can you see what the makers themselves truly experienced, and learn from the surprising challenges they faced and overcame. Here are some lessons we can all learn from the wonders of Eiffel’s Tower.

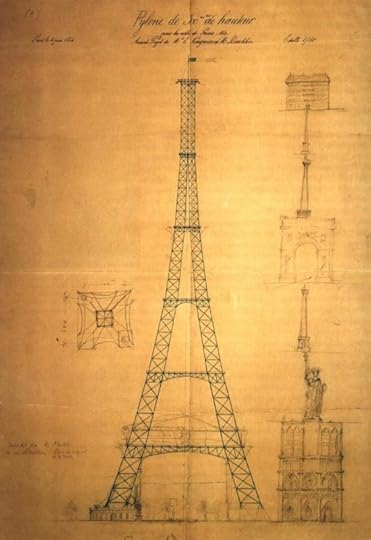

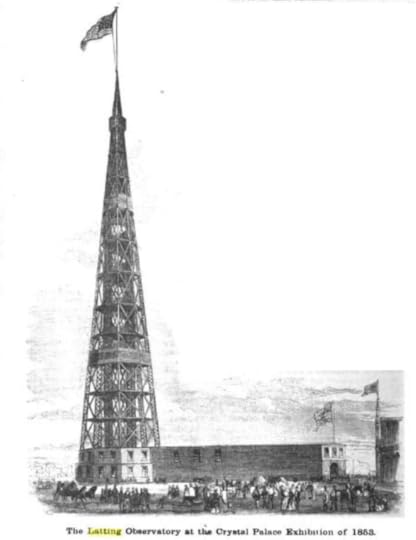

1. All Ideas Are Made From Other Ideas

Eiffel was inspired by the Latting Observatory, among other works. This tower, built in 1853, was taller than any other building in NYC, that is, until it burned down in 1856 (wood was still the primary construction material at the time, a fact Eiffel wanted to change). Eiffel also used engineering techniques found in nature to reduce weight and retain strength, essential concepts for constructing the tallest building in the world at the time. If you’re struggling to come up with good ideas, dig deeper into the surprising history of the major ideas in your own field. You’ll learn how they borrowed, reused and found inspiration from existing ideas.

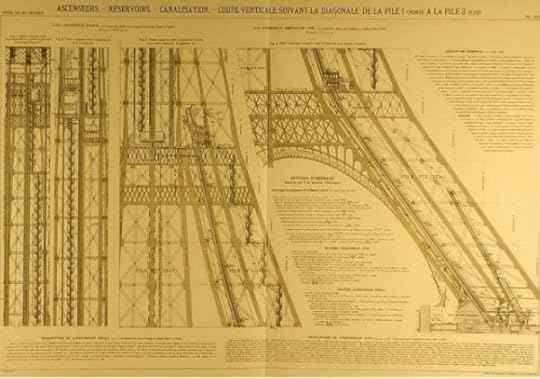

The design of the Eiffel tower was a wonderful combination of aesthetics and engineering (similiar in this regard to to the Brooklyn Bridge). But the plan for its style and construction evolved over time with contributions from at least four engineers. Maurice Koechlin and Émile Nouguier had the initial concept and drafted the first design (below), but it was rejected at first by Eiffel. They invited a third engineer, Stephen Sauvestre, who made several improvements, including the detailed latticework the tower would become famous for. Their revised design was finally accepted by Eiffel and proposed for the 1889 worlds fair (Exposition Universelle). Although the project bears his name, as only Eiffel had the reputation and finances to lead the project, the design of the tower had major contributions from others.

2. Conviction moves ideas forward

There were over 700 competing design submissions for the world’s fair tower (including this one from Bourdais, a major rival). Eiffel was fortunate to win, but the victory led to more challenges. The government surprised him by only offering $300k, a fraction of the what his proposed budget required. Eiffel chose to put in the remaining $1.3 million (5 million francs) himself. In return he asked for a 20 year lease and control over some of the pavilion area near the tower. This shrewd arrangement gave him the ability to advertise the other works his firm did, assuming of course that the tower itself was successful.

If your idea is turned down, what are you willing to put at stake as collateral (money or reputation) to make the project happen? If the person with the idea won’t stand behind it, why should they expect anyone else to?

Commitment to your own ideas is paramount. But also remember Franz Reichelt, as an example of conviction in an idea gone too far. He jumped from the Eiffel tower in 1912 to prove to the world that his parachute design worked, and fell to his death. You can even watch a film of his fatal attempt.

3. Even the best ideas meet resistance

Before the tower’s construction had begun, the French elite rejected its design. Soon 300 of the most well known artists and poets of Paris joined together as “The Committee of Three Hundred” to write an open letter to Eiffel and the city, demanding the project be stopped:

We, writers, painters, sculptors, architects and passionate devotees of the hitherto untouched beauty of Paris, protest with all our strength, with all our indignation in the name of slighted French taste, against the erection […] of this useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower… imagine for a moment a giddy, ridiculous tower dominating Paris like a gigantic black smokestack, crushing under its barbaric bulk Notre Dame, the Tour Saint-Jacques, the Louvre, the Dome of les Invalides, the Arc de Triomphe, all of our humiliated monuments will disappear in this ghastly dream… we shall see stretching like a blot of ink the hateful shadow of the hateful column of bolted sheet metal.

Even our wisest and best people, by human nature, resist new ideas. We forget that some of the greatest ideas we’ve had as a species faced great doubt on their long road towards acceptance. This means anyone with big ideas needs to understand that the best ideas don’t always win. Merit is not enough. It’s wise to expect resistance, invest in skills of persuasion and try to learn from the feedback you hear before you dismiss it. The reason why Eiffel won are, in part, due to the relationships he built the society of civil engineers, and the investments he made in explaining to them why his design was superior to others.

4. Long term commitments make history

The original agreement for the tower was that it would be torn down in 20 years. Part of the criteria for the design competition was that the tower must be engineered in a fashion that would make it easy to take apart. But Eiffel made careful investments in an attempt to prove the long term value of the tower. He never wanted it simply to be a decorative delight. Instead he imagined it as both a symbolic and practical embodiment of the future of science and technology.

He financed experiments in wireless telegraphy and radio, including the installation of one of the first antennas in France. This antenna proved sufficiently useful that it justified keeping the tower intact instead of destroying it, allowing it to remain the tallest building in the world for nearly 40 years. Eiffel even had a science laboratory installed not long after opening day, where experiments in meteorology, astronomy and even aerodynamics were conducted. His commitment to the long term vision of his idea is a major part of why the building still stands today and is loved by so many people for so many different reasons.

Recommended:

Eiffel’s Tower, by Jill Jones

Amazing Eiffel Tower construction photos

Eiffel’s tower – world’s largest billboard in 1925

Design submissions for 1890 London Tower

March 20, 2017

Dance of the Possible: Launch Recap (w/ Photos)

About 80 friends and fans joined me on Wednesday night to celebrate the launch of The Dance of the Possible. It’s a good chance to thank all the folks who’ve helped make my 14 year, 7 book, writing career possible, and share with them the launch of something new.

The book is on-sale now in Kindle and paperback, and you can read a free chapter here.

Below is a recap of the fun (including the list of topics people want me to write about in the future). Thanks to everyone who helped on launch day all around the world, with your pre-orders, tweets and FB shares!

If you came to the party – photos from the booth can be found here.

One of my favorite things about launch parties is the wall of suggestions, where anyone can put an idea for something I should write about on a post-it note. There were 62 of them, some wonderful, some bizarre, and some I can’t begin to explain. Here they are:

How to get paid to write

Ramen!

Life after Microsoft

Trump: is a social experiment?

Far right & Far left: why are they equally bad?

“Claustrophobia”

Gadzookery

Being Passionate without being a fanatic

1972: Fuck Yes!

Confirmation Bias in biz vs. life

Being maimed

Mushroom hunting

How Pokemon GO is the most important cultural phenomenon of our time

Tech success without being a jerk

Chocolate Bacon

Food culture change (Food trucks)

Aliens

The etymology of corporate buzzwords

A layperson’s guide/book to roads/transit/transportation and how it works

Why business is not politics

NYC vs. Seattle

Pancakes vs. Waffles

Washington’s farewell address and the future of American politics

Magic Mike XXL

A mystery novel

Encyclopedia of life-threatening UX Failures

Post-fordian semiotics of post-it notes

Immersion in middle america

Self-confidence: getting, keeping, displaying

The singularity

The elusive meaning behind everything

Dolphin milk

AI

What if our founding fathers were secretly aliens from another planet?

Linguistics semiotics meaning

Synergy!

New Jersey

Robot ethics

Post-thinking

Napster

A brief history of time where you rap w/ Stephen Hawking

Snakes on a plane

Systems

Myers-Briggs, yo.

Planet of the Apes, but with the GOP

50 cent’s descending career & existentialist journey

A “brief” history of the middle east

If the people faked it till they made it so can you

Why are people left handed?

My life as an introverted improvisationalist

Finding your inner-extrovert for introverts

Anything as long as it’s in 1337

Snuggies as formal attire

Body language, +1

Walt Disney’s cryo head

The ones who never succeed

The console wars

Encyclopedia of life-threatening ideas

Failure

Weird things I have encountered in my travels.

3D Printing in PJs.

When you are a tourist and arrested in Russia

The Dance of the Possible is on-sale now in kindle and paperback, and you can read a free chapter here. Hope you check it out! Thanks.

February 21, 2017

How Ignorance Drives Creativity

[In 22 days my latest book, The Dance of the Possible: the mostly honest completely irreverent guide to creativity, launches. I’ll be counting down the days until then with the story of an interesting idea, fact or story related to the book – you can see the series here]

“Knowledge is a big subject. Ignorance is bigger. And it is more interesting.” – Stuart Firestein

It should be no surprise that the forces involved in creative thinking can be counter-intuitive in nature. Often people use the framework of problem solving when talking about ideas, which is useful, but primarily logical. This makes the problem itself (“how can I build a better mousetrap?”) and the desire to solve the problem (“mice keep stealing all of my cheese”) provides the fuel to do the work.

It should be no surprise that the forces involved in creative thinking can be counter-intuitive in nature. Often people use the framework of problem solving when talking about ideas, which is useful, but primarily logical. This makes the problem itself (“how can I build a better mousetrap?”) and the desire to solve the problem (“mice keep stealing all of my cheese”) provides the fuel to do the work.

But a more surprising way of thinking about ideas is that it’s ignorance, the lack of knowledge, that can also be the motivating force, or at least curiosity about that lack of knowledge. Curiosity is an interest in finding out what you don’t know and you can only be curious about something if you have ignorance. If you know everything, there is nothing to be curious about (an observation that helps explain why know-it-alls are so dull to be around. They know everything but are curious about nothing).

Science is often used as a metaphor for things we completely understand. The common saying “the art and science of…” uses the word science to represent formulas, facts and figures, things that are well understood. But how did we learn those formulas and facts? We forget there must have been a time when we were ignorant of those things, and someone, a scientist perhaps, was curious enough to try and figure them out.

In Stuart Firestein’s wonderfully compact book Ignorance: how it drives science, he explores the central role that ignorance, and curiosity, play in developing all of the knowledge that we take for granted today.

I found obvious parallels to any kind of creative work, projects where the goal is to do something new, solve an unsolved problem or to work on anything challenging at all. For most people it is a surprise to read about creativity from this point of view, but it can be a revelation: if science can be thought of in this way, than so can any field or profession, including the one you work in too.

Here are some favorite quotes from the book:

Questions are more relevant than answers. Questions are bigger than answers. One good question can give rise to several layers of answers, can inspire decades-long searches for solutions, can generate whole new fields of inquiry, and can prompt changes in entrenched thinking. Answers, on the other hand, often end the process.

When I sit down with colleagues over a beer at a meeting, we don’t go over the facts, we don’t talk about what’s known; we talk about what we’d like to figure out, about what needs to be done.

What if we cultivated ignorance instead of fearing it, what if we controlled neglect instead of feeling guilty about it, what if we understood the power of not knowing in a world dominated by information? As the first philosopher, Socrates, said, “I know one thing, that I know nothing.”

There is no surer way to screw up an experiment than to be certain of its outcome.

Here are some examples of what have turned out to be good questions in my class: Do you think things are unknowable in your field? What? What are the current technological limits in your work? Can you see solutions? Where are you currently stuck? How do you talk about what you don’t know? What was the main thrust of your last grant proposal? What will be the main thrust of your next grant proposal? Is there something you would like to work on knowing but can’t? Because of technical limitations? Money, manpower? What was the state of ignorance in your field 10, 15, or 25 years ago, and how has that changed? Are there data from other labs that don’t agree with yours? How often do you guess? Are you often surprised? When? Do things come undone? What questions are you generating? What ignorance are you generating?

Almost everyone believes that the tongue has regional sensitivities— sweet is sensed on the tip, bitter on the back, salt and sour on the sides. Pictures of “tongue maps” continue to appear not only in popular books on taste and cooking but in medical textbooks as well. The only problem is that it’s not true. The whole thing arose from the mistranslation of a German physiology textbook by a Professor D. P. Hanig,

So some things can never be known and, get this, it doesn’t matter. We cannot know the exact value of pi. That has little practical effect on doing geometry.

Thomas Huxley once bemoaned the great tragedy of science as the slaying of a beautiful hypothesis by an ugly fact.

Faraday, by the way, had no idea what electricity might be good for and responded to a question about the possible use of electromagnetic fields with the retort, “Of what use is a newborn baby?” This phrase he apparently borrowed from Benjamin Franklin, no less, who was the first to make the analogy in his response to someone asking him what good flight would ever be after witnessing the first demonstration of hot air balloons.

wrong. Great scientists, the pioneers that we admire, are not concerned with results but with the next questions. The eminent physicist Enrico Fermi told his students that an experiment that successfully proves a hypothesis is a measurement; one that doesn’t is a discovery. A discovery, an uncovering— of new ignorance.

George Box, noted that “All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

Here are some examples of what have turned out to be good questions in my class: Do you think things are unknowable in your field? What? What are the current technological limits in your work? Can you see solutions? Where are you currently stuck? How do you talk about what you don’t know? What was the main thrust of your last grant proposal? What will be the main thrust of your next grant proposal? Is there something you would like to work on knowing but can’t? Because of technical limitations? Money, manpower? What was the state of ignorance in your field 10, 15, or 25 years ago, and how has that changed? Are there data from other labs that don’t agree with yours? How often do you guess? Are you often surprised? When? Do things come undone? What questions are you generating? What ignorance are you generating?

February 20, 2017

Inside the messy invention of the microwave oven

[In 23 days my latest book, The Dance of the Possible: the mostly honest completely irreverent guide to creativity, launches. I’ll be counting down the days until then with the story of an interesting idea, fact or story related to the book – you can see the series here]

In 1946 Dr. Percy Spencer of Raytheon Corporation was working on radar experiments with a magnetron (a device used to produce radio waves). When he noticed the candy bar in his shirt pocket had melted, he had every reason to throw it away, except one: he felt no heat. Odds are good that other people in radar laboratories around the world experienced similar globs of chocolate and other foodstuffs in their various pockets, and did nothing about them, other than to clean up the mess and get back to work. And given that the rational, logical parts of most intelligent people’s brains would tell them to do the same, getting rid of the offending savory bits and forgetting about it as soon as possible, it’s entirely odd that Spencer chose something different. Remember, he essentially found a bit of warm trash in his pocket, and chose to spend the rest of the day playing with melted cocoa beans, ignoring the millions of dollars of super cool top secret defense equipment surrounding him in his lab.

Just imagine Spencer in that moment: standing alone in a lab, expensive lights blinking on and off all around him, his eyes staring down at two chocolaty fingers, his Hershey stained clothes and lab coat crying out for care. If you walked past him at that instant you’d think for certain he was insane: a chocolate fingered loon. But although he didn’t know it yet, this chance encounter, the moment that redlined his curiosity well past his logical mind’s ability to follow, would lead him to the invention of the microwave oven. Curious about the source of heat, he put some popcorn kernels, and then an egg, by the nearest radar tube. The pop-corn popped, and the egg exploded. He quickly found support for more experiments, and spent the next ten years developing this chance encounter into one of the most used appliances in the world.

How else will new knowledge appear to us, if not as strange, bizarre or incomprehensible experiences? We forget that the common sense we hold dear today was, years or centuries ago, discovered by a curious mind willing to ignore the common sense of their own time. Any sane person would throw away his mistakes without a second thought, but an open mind might just stop and ask “how can I explain this?” before throwing it in the trash.

The microwave would take a long slow path to reaching consumers. The first commercially available designs in 1947 weighed over 700 lbs, were over 6 feet tall, and cost $5000 (about $40k today) . In 1971 only 1% of U.S. households had them. By 1986 it would rise to nearly 25%. Shown below, the Raytheon Mark V Microwave (1963) used mostly for commercial purposes. Note the four color button UI for different time settings.

[Excerpted, and revised, from Chapter 9 of The Myths of Innovation]

References:

RadarRange Central

Percy Spenser Bio

Other sources from The Myths of Innovation

February 16, 2017

How the Post-it Note Was Invented

[In 27 days my latest book, The Dance of the Possible: the mostly honest completely irreverent guide to creativity, launches. I’ll be counting down the days until then with the story of an interesting idea, fact or story related to the book – you can see the series here]

In 1968 Spencer Silver, with a PhD in organic chemistry, worked for 3M as a senior chemist. Among 3M’s most popular products at the time were different kinds of adhesives, and Silver worked on a project to create a new kind of stronger glue. Unfortunately his prototype was a failure: the glue was weak, too weak to be useful for anything. It was more of a sticky substance than a bonding glue. (No one knew it yet, but this substance contained an important discovery called microspheres, which would lead to a patent years later).

For many years Silver tried to find uses for this substance, but despite many experiments couldn’t find any. Most people would have given up, but he kept trying. In 1973 he had a new boss, Geoff Nicholson, and Spencer pitched him on the idea of using his creation on bulletin boards and other surfaces to make them sticky (eliminating the need for pushpins). But the potential seemed limited.

Another 3M employee named Art Fry saw a lecture by Silver where he talked about this curious substance he’d created and his inability to find uses for it. Fry sang in his church choir and would make notes on little pieces of paper over his sheet music when he practiced, but they often fell off or got lost. Fry and Silver worked together to create new prototypes for a paper with the weak glue that could be put on almost any surface. Fry suggested that Spencer’s design had it backwards: instead of making a surface sticky, the glue should be on the paper itself.

“We have a saying at 3M,” Dr. Nicholson said. “Every great new product is killed at least three times by managers.” (source). It was because of the support of Nicholson, Fry’s boss Bob Molenda, and the persistence of Spencer and Fry themselves, that they had the time to develop improved prototypes. Two more scientists, Roger Merrill and Henry Courtney, worked on inventing a coating for the paper that would keep the glue attached to it, rather than it being left behind on objects after the note was removed. The yellow color was chosen for convenience, according to Nicholson: it was what the lab next door had available, so they used it.

Prototypes of their work were popular in the 3M office, enough so that in 1977 executives approved a test release of a “Press ‘n Peel” product, as it was first called. A test release was required, in part, because the manufacturing machines would have to be redesigned to make this new product in large quantities, which may have contributed to internal resistance to the product. It seemed a very expensive proposition to build new production machines for a product that didn’t have, in the opinion of company veterans, high odds of success.

The response to the test release wasn’t positive – few people were interested in the product. Nicholson and others felt that the product wasn’t marketed well in this release, and that free samples needed to be given away so people could understand the concept. Finally in 1978 a second product release took place in Boise, with free samples, and it was a success. Soon the product was launched to the world in 1980 and is now one of the most popular office supply products in history.

Lessons:

You can’t predict what uses an idea will have, even if the idea is yours (“We never throw an idea away because you never know when someone else may need it” – Art Fry)

Spencer had to pitch his idea many times, in lectures and to his bosses, to obtain the attention it deserved

It can take years to develop an idea or invention into a meaningful concept

An idea, even a great one, needs to overcome organizational resistance

Rarely is there a lone inventor – most often a multitude of contributors are involved

Timeline:

12 years from idea to successful product

1968 – Silver’s “failed” glue prototype

1973 – Silver pitched new boss Nicholson on spray/bulletin board concept

1977 – “Press ‘n Peel” memo pad product in limited release, mixed response

1978 – Rereleased in Boise, ID (called the “Boise Blitz”) with free samples – strong response

1980 – National release of Post-it notes

References:

3M official History (and book)

Father of Post-it Notes

Interview with Spencer and Fry

Post-it note invention history (surprisingly thorough)

How the Post-It Note Was Invented

[In 29 days my latest book, The Dance of the Possible: the mostly honest completely irreverent guide to creativity, launches. I’ll be counting down the days until then with the story of an interesting idea, fact or story related to the book – you can see the series here]

In 1968 Spencer Silver, with a PhD in organic chemistry, worked for 3M as a senior chemist. Among 3M’s most popular products at the time were different kinds of adhesives, and Silver worked on a project to create a new kind of stronger glue. Unfortunately his prototype was a failure: the glue was weak, too weak to be useful for anything. It was more of a sticky substance than a bonding glue. (No one knew it yet, but this substance contained an important discovery called microspheres, which would lead to a patent years later).

For many years Silver tried to find uses for this substance, but despite many experiments couldn’t find any. Most people would have given up, but he kept trying. In 1973 he had a new boss, Geoff Nicholson, and Spencer pitched him on the idea of using his creation on bulletin boards and other surfaces to make them sticky (eliminating the need for pushpins). But the potential seemed limited.

Another 3M employee named Art Fry saw a lecture by Silver where he talked about this curious substance he’d created and his inability to find uses for it. Fry sang in his church choir and would make notes on little pieces of paper over his sheet music when he practiced, but they often fell off or got lost. Fry and Silver worked together to create new prototypes for a paper with the weak glue that could be put on almost any surface. Fry suggested that Spencer’s design had it backwards: instead of making a surface sticky, the glue should be on the paper itself.

“We have a saying at 3M,” Dr. Nicholson said. “Every great new product is killed at least three times by managers.” (source). It was because of the support of Nicholson, Fry’s boss Bob Molenda, and the persistence of Spencer and Fry themselves, that they had the time to develop improved prototypes. Two more scientists, Roger Merrill and Henry Courtney, worked on inventing a coating for the paper that would keep the glue attached to it, rather than it being left behind on objects after the note was removed. The yellow color was chosen for convenience, according to Nicholson: it was what the lab next door had available, so they used it.

Prototypes of their work were popular in the 3M office, enough so that in 1977 executives approved a test release of a “Press ‘n Peel” product, as it was first called. A test release was required, in part, because the manufacturing machines would have to be redesigned to make this new product in large quantities, which may have contributed to internal resistance to the product. It seemed a very expensive proposition to build new production machines for a product that didn’t have, in the opinion of company veterans, high odds of success.

The response to the test release wasn’t positive – few people were interested in the product. Nicholson and others felt that the product wasn’t marketed well in this release, and that free samples needed to be given away so people could understand the concept. Finally in 1978 a second product release took place in Boise, with free samples, and it was a success. Soon the product was launched to the world in 1980 and is now one of the most popular office supply products in history.

Lessons:

You can’t predict what uses an idea will have, even if the idea is yours (“We never throw an idea away because you never know when someone else may need it” – Art Fry)

Spencer had to pitch his idea many times, in lectures and to his bosses, to obtain the attention it deserved

It can take years to develop an idea or invention into a meaningful concept

An idea, even a great one, needs to overcome organizational resistance

Rarely is there a lone inventor – most often a multitude of contributors are involved

Timeline:

12 years from idea to successful product

1968 – Silver’s “failed” glue prototype

1973 – Silver pitched new boss Nicholson on spray/bulletin board concept

1977 – “Press ‘n Peel” memo pad product in limited release, mixed response

1978 – Rereleased in Boise, ID (called the “Boise Blitz”) with free samples – strong response

1980 – National release of Post-It notes

References:

3M official History (and book)

Father of Post-It Notes

Interview with Spencer and Fry

Post-It note invention history (surprisingly thorough)