Scott Berkun's Blog, page 11

September 21, 2016

On The Quest For Fun

Last week I saw Ian Bogost speak at Town Hall Seattle about his new book, Play Anything: The Pleasure of Limits, the Uses of Boredom, and the Secret of Games. Of the many ideas he offered about how to think about fun, he shared three stories that stayed with me more than anything else he said.

One day at the mall while walking with his daughter he noticed how, because she was bored, she made up a game of not stepping on the cracks in the floor tiles. I took this story to suggest we have the power to make many ordinary experiences fun if we are motivated to frame them that way. I believe this is true. The key to his daughter’s success might be that she was motivated to create, which raises the question: if she was never bored, would she ever be motivated to try to learn how to make things fun for herself? There are many things in life we know we want, but finding the motivation to go get them is the challenge. It seems counter-intuitive to have to expend effort to have fun, but maybe there’s a truth here that we don’t want to admit?

He criticized the notion popularized by Mary Poppins that “a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down” as an empty promise, and that covering one large unpleasant thing with a thin layer of something pleasant is a ruse and rarely works. It also dodges the question why isn’t the core of the experience made well on it’s own? He offered chocolate covered broccoli as another example – we’re fond of coating unpleasant things with tasty ones as a “solution”, but rarely is it as satisfying as simply making the central ingredient excellent (why not buy fresh broccoli and cook it lovingly so it tastes delicious itself?) I liked this thought, until I reconsidered his daughter’s choice: didn’t she cover over the boredom of the mall with the sugary distraction of a private game?

He shared how he chose to use a push lawn-mower, which takes more time and is far more frustrating to use than powered ones. He didn’t complete the story (perhaps he does in his book) or how it connected to his daughter, or Mary Poppins, but it was enough to make me consider that fulfillment can be more powerful than fun. The pleasure we take in finishing a hard project might be greater than spending the same amount of time doing something that was ‘fun and easy’. Game designers know they must balance the level of difficulty in their creations, making it simple enough to enjoy but hard enough to challenge us and keep our interest. And this was where the idea of fun fractured for me: fun isn’t really the goal, it’s pleasure or satisfaction that we’re after which are deeper concepts.

In the end I’m left feeling there’s something shallow about the isolated quest for fun, which I admit I was on as I was attracted to the lecture. Looking back now the very idea of going to a lecture about a book about fun seems like a very un-fun thing to do. The more time you spend thinking about fun, the less fun you’re probably having. It’s a common problem with philosophers, who in all of their thinking lose the very thread they’re trying to follow (e.g. great thinkers on life and love who failed to ever get a date). Inquiry is useful for a time, but soon there are diminishing returns in abstractions.

If I tried to explain all of this to someone half my age they’d think I was mad, as most twenty year olds are surrounded by people and situations heavily oriented towards having fun: it’s not something they’d think you need to go out and find. And in truth it wasn’t a particularly fun crowd or an especially entertaining experience, but who in their right mind would expect either of those things AT A LECTURE? This is not where people who are good at having fun go on a Friday night in Seattle (Yes, it was a Friday night. In my defense I DID have much fun at dinner with friends before we went to Town Hall, so there!)

One problem is the quest for fun assumes that we have binary states of fun or un-fun, which is about as true as always being either happy or unhappy. Our emotions are more sophisticated and that’s what makes us interesting. We can be happy and laugh in reminiscing about a tough day with a friend who was there, or, like Bogost’s daughter, use a very un-fun experience as the motivating force to create something more pleasing for ourselves. Fun is as multi-faceted as we are.

A great example of the limits of the term fun are the work experiences that are sold as entertainment. Learning how to be a chef, which is a job, is offered as a “fun and relaxing” experience for groups of friends. People love Crossfit, an exercise program that makes people as fit as marines, in part because of “the community that spontaneously arises when people do these workouts”. The dichotomy between work and play doesn’t hold up for long. Many people love their jobs because they find them fun, or at least enjoyable. When I watch a young band on stage at a concert, it certainly looks fun, even though I know they’ve worked hard at their craft and are technically working as I listen to them ‘play’.

It’s simply misguided to seek happiness, fun, or any singular emotional experience as if it were a product in a box. It’s just not a realistic understanding of how emotional experiences happen. As Victor Frankl wrote:

…happiness cannot be pursued; it must ensue. One must have a reason to “be happy.” Once the reason is found, however, one becomes happy automatically. As we see, a human being is not one in pursuit of happiness but rather in search of a reason to become happy, last but not least, through actualizing the potential meaning inherent and dormant in a given situation.

One related insight I learned from improv class is that fun things begin only when someone makes an offer. Someone has to make the first suggestion and give other people a chance to contribute in return. It can be as simple as inviting people out to lunch, to join you in a game, or even for a walk around the park. A wink, a nod, a smile, are all an offer of a kind. Someone has to initiate and create the possibility for an experience to happen. Like Bogost’s daughter we are always free to make offers to ourselves, to invent our own framework for the experiences we’re in, but some people find this much easier than others. Fun is easier to create when people we like, or are seeking fun as much as we are, are around us.

One approach is to think of the people in your life you find fun to be around: what is it that they do or say that makes you feel this way? I’d bet they simply make more offers, of the kind you like, when you are around them than other people do. They invite you into their stories, their jokes, or their hobbies, or find comfortable ways to invite themselves into yours. They share a sense of humor, or a sensibility, with you and offer ways to use that connection and grow it. If we want more fun in our lives then perhaps mostly we need to spend more time with these people or become more like them ourselves.

August 30, 2016

The 7 Questions For Any Tradition

A tradition is simply a custom that has been passed down from one generation to another. Their longevity can have many reasons, some good and some bad. We can not assume that persistence alone provides moral justification. Instead we must ask better questions about traditions before we judge their value.

The problem is we instinctively defend our traditions. We learn them when we are young, and when we grow older we naturally want to protect what we our elders taught us. Entire communities bond around traditions and rituals, and that is powerful uniting force, but it simultaneously creates great social pressure not to challenge them. We develop the illusion that they always existed in the form that we practice them, making it easy to confuse questioning a tradition with questioning the identity (or existence) of the community itself.

The danger is that in resisting change both regress and progress are prevented. It keeps the status quo strongly in place. If one goal of a society is to help the next generation have better lives than the previous, that goal demands a periodic reexamining of what those traditions were meant to do, and to compare them with the effect they have now.

It’s the confident community, and leader, who recognize a strong idea can withstand being questioned. And that a truly strong community will prefer to recognize a problem, and work to solve it, rather than hide behind the defense of longevity.

7 questions to ask of any tradition:

When and why did the tradition it start?

What problem was it intended to solve? (See Chesterton’s Fence)

How did it change over time? (every tradition has changed over time)

Is the problem it was intended to solve still a problem?

What ideas are we using the tradition to honor, remember or pass on to future generations?

Can we carefully adjust this tradition to make it more effective to pass on those ideas?

Do we need to redefine this tradition given all we’ve learned since it started?

One of the most popular traditions in the world, and one that serves as a great example, is birthdays. Most of the world celebrates them today, but this wasn’t always the case. The Egyptians invented the practice in ancient times but it was limited to recognizing their gods. Then it was the Greeks who began the practice of lighting candles on the cakes they offered to the divine. Later it was the Romans who were the first to celebrate the birthdays of ordinary people (but only men). At that time Christians didn’t celebrate the birth of anyone, seeing birthdays as highly egotistical and pagan in nature. It was only in 336 that the first Christmas was celebrated. On and on through the centuries this tradition has changed in meaning and significance, used in different ways, in different cultures, to honor or ignore, different people for different reasons.

The lesson is that what we do today will be someone else’s history. All traditions are living things, shifting and changing, sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse, but they are all in motion, just at a pace we rarely notice. The more we can see traditions as just one of the many forces that tie us together, the better we can use them to help us protect and improve what’s best in our families, societies and civilizations.

“Every tradition we hold dear was once a new idea someone proposed, tried, and found valuable, often inspired by a previous tradition that had been outgrown. The responsibility of people in power is to continually eliminate useless traditions and introduce valuable ones. An organization where nothing ever changes is not a workplace but a living museum.” – From The Year Without Pants

Related:

Innovation vs. Tradition: Christianity, the Vatican and Sin

August 24, 2016

The Real World of Technology (Book Review)

Despite our cultural obsession with new technology, we forget that the idea of new technology is old. We also overlook that there are patterns for how new technologies impact cultures and societies that technologists are often ignorant of. Without understanding the social impact of past technologies, we’re more likely to repeat mistakes, since we don’t even know what to look for.

Recently I read The Real World of Technology, a short book by Ursula Franklin (Thanks Deb Chachra for the recommendation). It’s more academic in style than other culture/technology books I recommend, like my favorite book on the subject, Technopoly, but it had insights that were new to me. In a series of short chapters she identifies and addresses important observations about the sociology of technological change, and how, without us noticing, our choices have impacted us more than we think.

Recently I read The Real World of Technology, a short book by Ursula Franklin (Thanks Deb Chachra for the recommendation). It’s more academic in style than other culture/technology books I recommend, like my favorite book on the subject, Technopoly, but it had insights that were new to me. In a series of short chapters she identifies and addresses important observations about the sociology of technological change, and how, without us noticing, our choices have impacted us more than we think.

One of her primary observations is the distinction between holistic and prescriptive technology. A holistic technology means the creator controls the process of their own work from beginning to end:

Their hands and minds make situational decisions as the work proceeds, be it on the thickness of the pot, or the shape of the knife edge, or the doneness of the roast. These are decisions that only they can make while they are working. And they draw on their own experience, each time applying it to a unique situation.

Whereas a prescriptive technology is bound in defined steps and rules, with an obvious example being the assembly lines found at any factory in the last 150 years:

When work is organized as a sequence of separately executable steps, the control over the work moves to the organizer, the boss or manager. The process itself has to be prescribed with sufficient precision to make each step fit into the preceding and the following steps. Only in that manner can the final product be satisfactory. The work is orchestrated like a piece of music — it needs the competence of the instrumentalists, but it also needs strict adherence to the score in order to let the final piece sound like music.

Many technologies, like a guitar or a word processor, involve holistic and prescriptive elements. To play a song on a guitar I’m confined to six strings and 19 frets, and to write a poem, I’m confined to a language (and a keyboard of a specific design). But within those constraints I’d be free to work holistically, or even, to the core of Franklin’s point, decide on my own if I’d prefer a different tool (perhaps a fretless guitar).

But her primary point is often technology, is especially as applied by organizations, is prescriptive by design or accident. And that corporations and bureaucracies can use technologies in prescriptive ways that only serve their own longevity.

More salient quotes from the book:

Any tasks that require caring, whether for people or nature, and any tasks that require immediate feedback and adjustment, are best done holistically. Such tasks cannot be planned, coordinated, and controlled the way prescriptive tasks must be.

Today’s real world of technology is characterized by the dominance of prescriptive technologies. Prescriptive technologies are not restricted to materials production. They are used in administrative and economic activities and in many aspects of governance, and on them rests the real world of technology in which we live. While we should not forget that these prescriptive technologies are often exceedingly effective and efficient, they come with an enormous social mortgage. The mortgage means that we live in a culture of compliance, that we are ever more conditioned to accept orthodoxy as normal, and to accept that there is only one way of doing it.

“Size is a natural result of growth, but growth itself cannot be commandeered; it can only be nurtured and encouraged by providing a suitable environment. Growth occurs; it is not made. Within a growth model, all that human intervention can do is to discover the best conditions for growth and then try to meet them. In any given environment, the growing organism.”

“Production, then, is predictable, while growth is not. There is something comforting in a production model — everything seems in hand, nothing is left to chance — while growth is always chancy.”

“The unchallenged prevalence of the production model in the mindset and political discourse of our time, and the model’s misapplication to blatantly inappropriate situations, seems to me an indication of just how far technology as practice has modified our culture.”

“Yet for people all around the world the image of what is going on, of what is important, is primarily shaped by the pseudo-realities of images. The selective fragments that become a story on radio and television are chosen to highlight particular events. The selection is usually intended to attract and to retain the attention of an audience. Consequently, the unusual has preference over the usual.”

“Anyone who has ever been at a demonstration and then seen their own experience played back on television knows what I mean. Frequently a small counter-demonstration to a large demonstration is treated as if it were the main event. Side-shows move into the centre and the central issues become peripheral.”

“I find it hard to imagine anyone actually standing next to a person who is being hurt or abused and enjoying the sight and sound of the experience, nor can I imagine such a direct observer not intervening or at least feeling guilty for having failed to do so. On the other hand, violence depicted on a screen appears to be acceptable and entertaining.”

August 8, 2016

The 7 Questions For Any Technological Idea

From Neil Postman’s lecture On Culture’s Surrender to Technology:

What is the problem that this new technology solves?

Who’s problem is it?

What new problems do we create by solving this problem?

Which people and institutions will be most by a technological solution?

What changes in language occur as the result of technological change?

Which shifts in economic and political power might result when this technology is adopted?

What alternative uses might be made of a technology?

July 28, 2016

Staying Sane In An Insane World

How would you explain the events of 2016 to someone from the year 2050 who time traveled to visit us? Many adjectives come quickly to mind: turmoil, danger, violence, drama, unrest, uncertainty. But if you think deeper about trying to explain what it all means, you’d realize this challenge is impossible. We couldn’t tell someone from the future about 2016 because we can’t understand 2016 yet: we don’t know what happens next! We don’t have the context to make sense of these events. If we were alive in 1776, 1914, 1968 or 2001 we’d have a similiar problem. We can describe the significance of those years now only because we know what happens after.

It must be said that we are a stubborn and frustrating species. Too often we wait for terrible things to happen before we’re willing to change our minds, or change anything at all. It’s not a rule, as history doesn’t depend on rules, but unrest and disorder are sometimes necessary to wake us up and motivate us to grow. And to remind us we share our fates with each other. In the end, the best we could tell our friend from 2050 is “something is happening!” We truly are living in an interesting time.

Contrary to the title of this essay, I don’t think the world is insane. Instead it’s more that we’re designed to live at the scale of tribes, not cities and nations (See Freud’s Civilization and It’s Discontents, where he suggests we traded sanity away to get more security and stability). It’s not the world’s fault, in a sense, but our own.

When I get past my own emotions and rantings, I conclude three things about this year so far:

We’re addicted to news and news is shallow. Neil Postman said “information is a form of garbage” meaning that at a certain volume more information does not help you. The speed and quantity of news, which we presume to be an asset, does not help us gain perspective, understanding or meaning, the three things we want most. Most forms of news are not helpful, but they are plentiful and addictive.

Our brains are poor at calibrating to a national or planetary scale. We’re easily misled by dramatic (but possibly unrepresentative) news. And we’re quick to use one narrow string of events to define our feeling of “how the world is”. Combined with cognitive bias, we’re prone to strong emotions based on irrational assumptions.

Big problems we’ve ignored are now un-ignorable. The violence, racism, classism, anger and fear that have fueled the worst events these past months did not suddenly appear. Instead it’s the consequence of years, or decades, of problems we haven’t solved, or perhaps have largely ignored. Technology may have made these problems far more visible, but they were likely there all along.

The world, on average, is getting better. Many people refer to statistics that show that by many measures the world has been a steadily improving place. This is good and hopeful news: if you need a boost of positiveness, then look at these charts.

But the trap of that last point is the flaw of averages: simply because the total average, of say violent crime in america, has gone down for a decade, doesn’t mean there aren’t sizable pockets where crime is going up. Averages can be misleading. For example, on average the universe is a very dead and boring place, but that average makes it seem like Paris or Las Vegas don’t exist. But they do! Statistics tend to oversimplify – they’re useful but rarely definitive.

My advice is simple. We are emotional creatures, so find a healthy way to vent the negative energy that you feel. Go to the gym, or for a hike, and let your feelings out through exercise, which we all know we need more of. Scream at the sky and challenge the wind. But don’t target your rage at people, certainly not at strangers: the golden rule is a good guide here.

Another safe place to express yourself is a private journal, where any idea on your mind can be expressed safely and without judgement (Social media isn’t quite the same, because you are expressing yourself with the knowledge that someone is observing you). Or talk to friends who care about how you feel (and if you don’t have friends who care about your feelings, your real problem might be you need to find better friends).

But then, once you’ve expressed those emotions… slow down. Be curious. Seek thoughtful points of view that differ from your own: it’s the only way to provoke your own thinking to improve (instead of just responding and sharpening your preconceptions). Talking to people who agree with you on everything will teach you nothing.

I’ve read so much these last few months seeking answers. I don’t look to the news for meaning, because that’s not what it’s good for: instead I try to read deeper. Here are five essays, with varying views, that helped me to feel I understand what’s going on (or clarifying what I don’t understand). I don’t necessarily endorse their positions but to my point above, they help in the pursuit of understanding:

American is not on the verge of disaster. A historian puts current events in a historic context and suggests we slow down.

History tells us what’s next. A historian takes the opposite view about the world, and thinks we’re in big trouble (I agree more with the first one, but this one has its merits too. I’d like to see these two folks debate).

Why Are So Many Black Americans Killed By Police? A thoughtful and careful examination of the many possible factors and implications, centered on various statistics.

Trump: Tribune of Poor White People – This excellent interview helped me better understand support for Trump. As did this lecture by Thomas Frank on the economic failures of Clinton and Obama.

How Do People Change Their Minds? A good reminder that most expressions of opinions in social media have little effect. Venting is one thing, thoughtfully trying to influence a mind is another.

How To Discuss Politics with Friends, version 2.0. My simple guide for healthier conversations about tough topics.

July 20, 2016

Quote of the week, from Viggo Mortensen

One of my favorite podcasts is Here’s the Thing, and on a recent episode host Alec Baldwin interviewed Viggo Mortensen about his latest film, Captain Fantastic. Towards the end he mentioned this:

“By taking the risk of trying hard means you are going to make mistakes, and then the most important thing is hopefully realizing that and doing something about it. Being a good dad is not a static thing. Having a good marriage isn’t a static thing. Neither is a democracy. Neither is a friendship. Tomorrow morning you have to start over, continue the process and make adjustments. And if you don’t… it’s a game that moves as you play, and if you don’t move you can’t play”

Viggo Mortensen, on Here’s The Thing

June 16, 2016

Five Ways To Survive Fathers Day

Father’s Day is always a tricky time for me. I had a tough relationship with my father, and the day has often made me sad. I’d see friends celebrate and think of what I wish I had experienced, but never will. Many people have similiar stories to mine, or their father’s are no long alive, making the day a complicated one.

Father’s Day is always a tricky time for me. I had a tough relationship with my father, and the day has often made me sad. I’d see friends celebrate and think of what I wish I had experienced, but never will. Many people have similiar stories to mine, or their father’s are no long alive, making the day a complicated one.

In writing the book The Ghost Of My Father (reviews / free excerpt here), I discovered a different way to feel about Father’s Day. I redefined the day into something positive.

Here are five ways to get through Father’s Day if it’s a difficult time for you:

Make it “men who helped you” day. Make a list of other men (or women if no men qualify for you) who helped you in your life. Give them a gift or write them a note that you’re grateful for what they did. Perhaps a high school teacher or coach? A boss who mentored you? Or even an older friend, or uncle, who has given you fatherly advice now and then. Let them know that they helped you.

Honor good fathers you know in your community. Do you have a friend who is a good father to their children? Father’s day gifts from children can feel obligatory, but a thoughtful note from a friend, someone who has no obligation, can mean a great deal to them (and to you). Tell them what you’ve noticed and why you appreciate the kind of father they are.

Help other children without fathers. Nearly 30% of American children grow up without a father in their home. Whatever your story was, these are innocent children who might need help that you can provide. Donate to Extended Family, The National Fatherhood Initiative or other non-profits focused on helping families without fathers.

Consider fathers from movies and books that have inspired you (Candidates include: To Kill A Mockingbird, Contact, Boyz ‘n The Hood or even Life Is Beautiful. See: Ten Best Movie Dads). A fictional father can still provide guidance or even be a role model. You can choose to think about them on Father’s Day and write in your journal about why those characters have earned a place in your memory.

Think about becoming a mentor. Help a young person get some of the support and guidance you didn’t get (or that you did get and want to pay forward). Big Brothers Big Sisters is a great place to start, and the first edition of Ghost of My Father donated a portion of the proceeds to them. I was a Big Brother myself and highly recommend participating. It can change how you feel about your past, and your future, in profound ways.

Work on your relationship. If your father is still alive, take a chance and reach out. My father died last year, and I’m out of chances to ever try and reconcile again, but perhaps there is hope for you. Instead of a cliche gift, buy a book about fathers and sons and give it as a gift, with a note asking him to have a conversation about it. The Great Santini and Big Fish are challenging places to start (and were made into excellent films). If you’ve done this and have book recommendations, leave a comment (particularly for books on father / daughter relationships, which seem harder to find)

May 24, 2016

How To Be a Better Speaker – The Short Honest Truth

For any skill, you only improve through practice. Reading is not practice. Watching other people do something is not practice. Reading and watching help only if you apply what you learn while you are practicing. Most people do not practice, which is why most people are bad at most things, including public speaking.

The most important thing to practice is thinking. Think about these questions:

– Why is your audience there? What problem are they trying to solve?

– What 5 questions do they want you to answer on the topic?

– What work do you need to do to give great, practical answers?

– What simple outline best expresses your answers, and gives a sense of progression?

Most speakers don’t spend enough time crafting the core ideas in their talk. Instead, most speakers get lost in superficials: looking good, sounding good, and having fancy slides. But the reason people show up to a conference or presentation is rarely for superficials – it’s to get answers and encouragement. It’s not about the speaker, it’s about the audience. The one talk that solves the most problems for the most people will be the best remembered. If you give the audience ways to solve their problems, they’ll overlook many superficial mistakes. This requires hard work. Good public speaking is based on good private thinking.

Speaking is actually comprised of many different skills: writing, storytelling and performing. A good presentation combines them all into one experience.

People worry the most about performing. The best possible way to improve performance is to (surprise!) practice. Take a few minutes of your material, before you make any slides, and do a practice run, and then record it on video. Then watch it. Ask friends you know will give you tough feedback to watch it. Take notes on places where you get lost, where your points can be clearer and distracting habits you might have. Then do it again. Revise and rewrite. And practice again. Practice is the only way to change habits, improve your thoughts and get comfortable with your own material.

When you see a presentation that is smart, polished and looks natural, never forget how much effort was required to make it seem so effortless.

Related:

Read my bestseller, Confessions of a Public Speaker, with honest chapters on practical advice for everything you need to be a better speaker

Archive of public speaking advice on this blog

Download the free “how to prepare for a talk” checklist (PDF)

(Note: originally posted on Quora)

May 11, 2016

The Simple Plan for People That Want To Solve Big Problems

[This is an excerpt from chapter 12, of the bestseller, The Myths of Innovation]

The Simple Plan

If you want to make progress happen, or be someone who brings good ideas into the world, this is for you. It’s the simplest, easiest, most straightforward way to convert your ambition into action. When I’m asked to give advice about managing creativity or how to make an organization “innovative” this is what I share.

Pick a project and start doing something. It almost does not matter what it is. You will need many experiences in trying to develop ideas into things before you’ll be good at it, especially if you are working with other people. Don’t wait around. Go make a website. Write a draft. Make a prototype. Have a small ambition you can manifest quickly so the stakes are low, and the pace is fast. Until you start working on something, you won’t truly start learning. The temptation is to have a grand sounding universal plan, don’t give in to it. That can come later. Think of these early attempts as scouting for ideas. Before you can build a city, you’d thoughtful scout and map the landscape. And if you can’t find a way to start a project at work, do it on weekends – history is full of creative heroes who never had approval from anyone to do it. There is always a way to start, just pick something small enough you can do yourself in an afternoon, or with a friend, and get to work.

Forget the word innovation: focus on solving a problem. Most products out in the world are not very good. You rarely need a breakthrough to improve things, to beat the competition, or to help people suffering from a problem. If you carefully study the problem you’re trying to solve, you will discover many clear ways, some forgotten or executed poorly, to make it better. That’s the best place to start. If you solve a problem for a customer than makes them happy and earns you money, do you really think they will care if it’s “innovative” or “breakthrough”? They just want their problems solved. If you cured cancer conventionally, would the patients refuse, saying “but it’s not innovative.” Of course not. Often it’s the combination of many conventional solutions, the combination obscuring how old some of the ideas were, that is called an innovation afterwards by people ignorant of the history of those ideas. So don’t worry. Sometimes small ideas, applied well, matter more than big ideas. Try to use workmanlike language: problem, prototype, experiment, customer, design, and solution, instead of the jargon of breakthrough, radical, game-changing and innovative. This keeps you low to the ground, and prevents your ego from distracting you away from simply making good things.

If you work with others, you need leadership and trust. There’s no point worrying about which innovation method you’re using, or how much budget you’re going to spend, if people don’t trust each other. It’s the leader’s job to create an environment of trust so ideas move freely and can grow. Developing new ideas is scary and demands vulnerability and if people don’t trust each other their talents will never be revealed. It’s also the leader’s role to use their superior power to take risks, and protect the team from the dangers of those risks. This sounds obvious, but look around. It’s rare. Many people do not trust their teams, nor work for leaders who are willing to stake their reputations on the risks of a new idea. It’s uncommon to find someone in power who is willing to take the blame for problems, but also willing to give credit to subordinates as rewards for their efforts. If you’re a leader, the burden is on you. If you’re not, and you don’t work for someone who creates trust and is willing to take risks, good work will not happen where you are. Either move, find the courage to take a bet and force the issue, or accept the status quo.

If you work with others, and things are not going well, make the team smaller. There is a reason great things often happen in small organizations. With fewer people, there are fewer cooks and fewer egos. In many large organizations there are too many people involved for anything interesting to happen. The first advice I give teams when things are not going well is to kick people out of the room. If you’re the boss, you should volunteer yourself to leave. Do whatever is necessary to reduce the number of people involved in making decisions. The dynamic of getting 3 people to agree to take a risk together is dramatically simpler than getting 30 people to do the same. Three people will be fully invested and passionate about a decision in ways thirty people never are. Another solution is to pick one creative leader, and give them more power. A film director is the singular creative leader on a movie. Yet most corporate or academic projects divide up leadership across committees, diffusing authority, which always makes decisions more conservative, the opposite of what you want.

Be happy about interesting ‘mistakes’. If you are doing something new, it can not go well on the first, second, or possibly 50th time. This is OK. Your mindset has to be, ‘This did not go how I expected, but I expected that. What can I learn so the next attempt improves? (or teaches more interesting lessons)” The more interesting the lesson, the better. It’s the mind of an experimenter (see Chapter 3) that you want to cultivate, asking questions about everything you make, and using the answers to those questions to fuel the next attempt and the next. Many people quit on their 2nd or 3rd try at something, for reasons that have nothing to do with the history of innovation. There was not a story in this book where any of the brilliant minds mentioned succeeded on such a small number of tries. Perseverance, as simple a concept as it is, is rare. The more ambitious the problem you’re trying to solve, the more experiments and attempts you will need to get it right.

It’s uncommon to people or organizations that follow these 5 basic notions. Yet I’m convinced the ones that do have the highest odds of producing good work, in a healthy culture, with results the team and the customers are proud of. The challenge is commitment is required to stay focused on the simple plan. You’ll dream of an easier way, and hope for a trick or formula or magical method to avoid the work and the risks. You will find many consultants and experts who promise you things that do not exist. But I hope that the stories you read earlier in this book will anchor your confidence, defend you against the many myths, and help this simple view stay with you.

[This is an excerpt from chapter 12, of The Myths of Innovation]

March 31, 2016

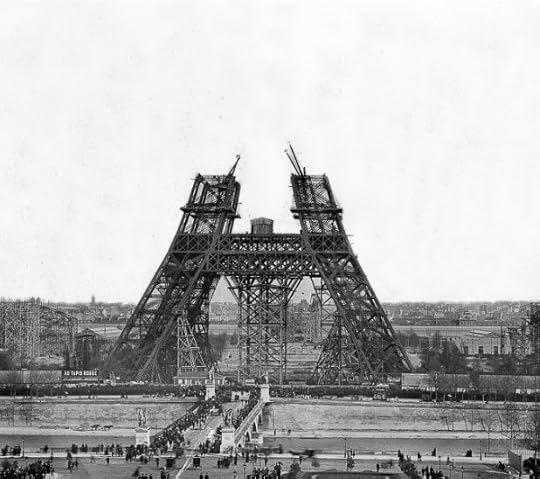

What We Can Learn From The Eiffel Tower

We take great works for granted. We forget, but the fate of even our most famous ideas and creations was far from certain at the time they were proposed. A powerful exercise anyone can do is to pick a famous creation and go back in history to the days before it was made. Only then can you see what the makers themselves truly experienced, and learn from the surprising challenges they faced and overcame. Here are some lessons we can all learn from the wonders of Eiffel’s Tower.

1. All Ideas Are Made From Other Ideas

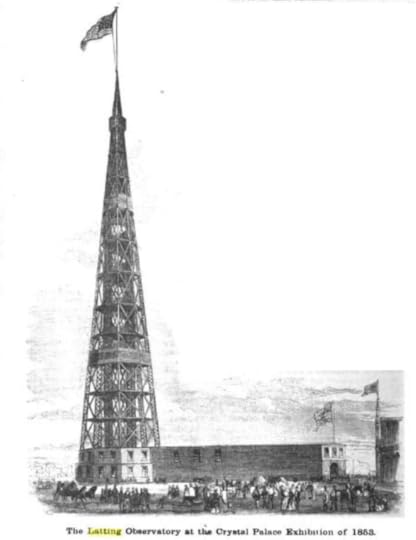

Eiffel was inspired by the Latting Observatory, among other works. This tower, built in 1853, was taller than any other building in NYC, that is, until it burned down in 1856 (wood was still the primary construction material at the time, a fact Eiffel wanted to change). Eiffel also used engineering techniques found in nature to reduce weight and retain strength, essential concepts for constructing the tallest building in the world at the time. If you’re struggling to come up with good ideas, dig deeper into the surprising history of the major ideas in your own field. You’ll learn how they borrowed, reused and found inspiration from existing ideas.

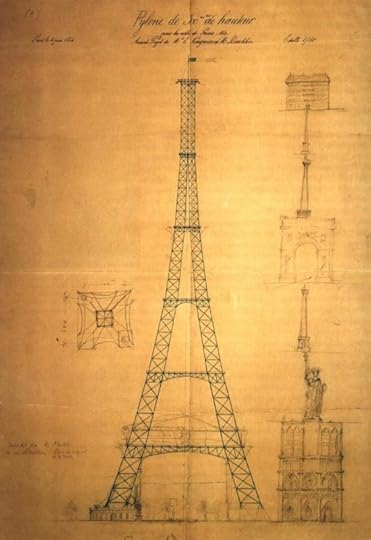

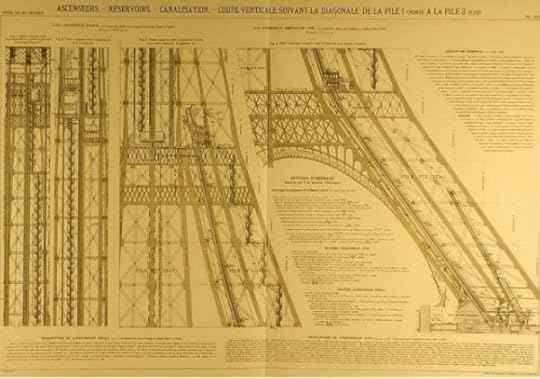

The design of the Eiffel tower was a wonderful combination of aesthetics and engineering (similiar in this regard to to the Brooklyn Bridge). But the plan for its style and construction evolved over time with contributions from at least four engineers. Maurice Koechlin and Émile Nouguier had the initial concept and drafted the first design (below), but it was rejected at first by Eiffel. They invited a third engineer, Stephen Sauvestre, who made several improvements, including the detailed latticework the tower would become famous for. Their revised design was finally accepted by Eiffel and proposed for the 1889 worlds fair (Exposition Universelle). Although the project bears his name, as only Eiffel had the reputation and finances to lead the project, the design of the tower had major contributions from others.

2. Conviction moves ideas forward

There were over 700 competing design submissions for the world’s fair tower (including this one from Bourdais, a major rival). Eiffel was fortunate to win, but the victory led to more challenges. The government surprised him by only offering $300k, a fraction of the what his proposed budget required. Eiffel chose to put in the remaining $1.3 million (5 million francs) himself. In return he asked for a 20 year lease and control over some of the pavilion area near the tower. This shrewd arrangement gave him the ability to advertise the other works his firm did, assuming of course that the tower itself was successful.

If your idea is turned down, what are you willing to put at stake as collateral (money or reputation) to make the project happen? If the person with the idea won’t stand behind it, why should they expect anyone else to?

Commitment to your own ideas is paramount. But also remember Franz Reichelt, as an example of conviction in an idea gone too far. He jumped from the Eiffel tower in 1912 to prove to the world that his parachute design worked, and fell to his death. You can even watch a film of his fatal attempt.

3. Even the best ideas meet resistance

Before the tower’s construction had begun, the French elite rejected its design. Soon 300 of the most well known artists and poets of Paris joined together as “The Committee of Three Hundred” to write an open letter to Eiffel and the city, demanding the project be stopped:

We, writers, painters, sculptors, architects and passionate devotees of the hitherto untouched beauty of Paris, protest with all our strength, with all our indignation in the name of slighted French taste, against the erection […] of this useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower… imagine for a moment a giddy, ridiculous tower dominating Paris like a gigantic black smokestack, crushing under its barbaric bulk Notre Dame, the Tour Saint-Jacques, the Louvre, the Dome of les Invalides, the Arc de Triomphe, all of our humiliated monuments will disappear in this ghastly dream… we shall see stretching like a blot of ink the hateful shadow of the hateful column of bolted sheet metal.

Even our wisest and best people, by human nature, resist new ideas. We forget that some of the greatest ideas we’ve had as a species faced great doubt on their long road towards acceptance. This means anyone with big ideas needs to understand that the best ideas don’t always win. Merit is not enough. It’s wise to expect resistance, invest in skills of persuasion and try to learn from the feedback you hear before you dismiss it. The reason why Eiffel won are, in part, due to the relationships he built the society of civil engineers, and the investments he made in explaining to them why his design was superior to others.

4. Long term commitments make history

The original agreement for the tower was that it would be torn down in 20 years. Part of the criteria for the design competition was that the tower must be engineered in a fashion that would make it easy to take apart. But Eiffel made careful investments in an attempt to prove the long term value of the tower. He never wanted it simply to be a decorative delight. Instead he imagined it as both a symbolic and practical embodiment of the future of science and technology.

He financed experiments in wireless telegraphy and radio, including the installation of one of the first antennas in France. This antenna proved sufficiently useful that it justified keeping the tower intact instead of destroying it, allowing it to remain the tallest building in the world for nearly 40 years. Eiffel even had a science laboratory installed not long after opening day, where experiments in meteorology, astronomy and even aerodynamics were conducted. His commitment to the long term vision of his idea is a major part of why the building still stands today and is loved by so many people for so many different reasons.

Recommended:

Eiffel’s Tower, by Jill Jones

Amazing Eiffel Tower construction photos

Eiffel’s tower – world’s largest billboard in 1925

Design submissions for 1890 London Tower