Scott Berkun's Blog, page 10

February 15, 2017

Why no one cared about the Wright brothers airplane

[In 30 days my latest book, The Dance of the Possible: the mostly honest completely irreverent guide to creativity, launches. I’ll be counting down the days until then with the story of an interesting idea, fact or story related to the book – you can see the series here]

When the Wright brothers landed from their famous flight at Kitty Hawk on December 1903 almost no one was there: just five people including a boy from the neighborhood. This is surprising to us in the present because in the nearly 114 years since that day airplanes have become central to modern life. But at the time airplanes were mostly a curiosity. Many other inventors over the centuries had attempted, and in some cases succeeded, at different variants of assisted and even powered flight. But the world shrugged at them all. “What problem does this solve?” was an excellent and largely unanswered question for these men and their machines.

Even the Wright brothers themselves weren’t entirely sure what powered flight could achieve. They passionately believed the invention would help end wars, as the power to see enemies from above would, in their thinking, eliminate the incentive to attack at all. Given the central role airplanes have played in modern warfare for decades this notion seems terribly naive, but inventors often are. The ability to create something doesn’t come with the ability to predict the future (although often often comes with enough hubris to make the inventor believe otherwise). Regardless, they faced a more pressing problem after their famous flight. Almost no one in the U.S. was interested in their creation for any purpose at all.

The Wright brothers had to go to Europe for a time to try and to sell their ideas, and it took many months before they found their first customers. They finally negotiated a contract with the U.S. government in 1907. It was the first military contract in aviation history. It took four years to get someone to pay for their airplane design.

What can we learn:

When you do something truly significant, the world may not understand or care (see Why The Best Idea Doesn’t Always Win). Selling an idea is often harder than coming up with one. (“Don’t worry about people stealing an idea. If it’s original, you will have to ram it down their throats.” – Howard Aiken)

It’s hard to predict how new ideas will be used, even for their inventors

Progress and change happens far slower than we think (and history helps remind us of this fact)

Asking “what problem does this solve?” is a powerful tool – but not having a clear answer does not mean the idea is useless (although it might be). It may just mean the use hasn’t been discovered yet. Working on new ideas is a dance with both the possible and the impossible.

The detailed invention story of the Wright brothers airplane is one of my favorites and among the most rewarding, as they patiently applied problem solving, research and invention approaches without any formal training. An inspiring, and well illustrated, read is How We Invented The Airplane by Orville Wright.

Why no one cared about the Wright brothers’ airplane

[In 3o days my latest book, The Dance of The Possible: the mostly honest completely irreverent guide to creativity, launches. I’ll be counting down the days until then with the story of an interesting idea, fact or story related to the book]

When the Wright brothers landed from their famous flight at Kitty Hawk on December 1903 almost no one was there: just five people including a boy from the neighborhood. This is surprising to us in the present because in the nearly 114 years since that day airplanes have become central to modern life. But at the time airplanes were mostly a curiosity. Many other inventors over the centuries had attempted, and in some cases succeeded, at different variants of assisted and even powered flight. But the world shrugged at them all. “What problem does this solve?” was an excellent and largely unanswered question for these men and their machines.

Even the Wright brothers themselves weren’t entirely sure what powered flight could achieve. They passionately believed the invention would help end wars, as the power to see enemies from above would, in their thinking, eliminate the incentive to attack at all. Given the central role airplanes have played in modern warfare for decades this notion seems terribly naive, but inventors often are. The ability to create something doesn’t come with the ability to predict the future (although often often comes with enough hubris to make the inventor believe otherwise). Regardless, they faced a more pressing problem after their famous flight. Almost no one in the U.S. was interested in their creation for any purpose at all.

The Wright brothers had to go to Europe for a time to try and to sell their ideas, and it took many months before they found their first customers. They finally negotiated a contract with the U.S. government in 1907. It was the first military contract in aviation history. It took four years to get someone to pay for their airplane design.

What can we learn:

When you do something truly significant, the world may not understand or care (see Why The Best Idea Doesn’t Always Win). Selling an idea is often harder than coming up with one. (“Don’t worry about people stealing an idea. If it’s original, you will have to ram it down their throats.” – Howard Aiken)

It’s hard to predict how new ideas will be used, even for their inventors

Progress and change happens far slower than we think (and history helps remind us of this fact)

Asking “what problem does this solve?” is a powerful tool – but not having a clear answer does not mean the idea is useless (although it might be). It may just mean the use hasn’t been discovered yet. Working on new ideas is a dance with both the possible and the impossible.

The detailed invention story of the Wright brothers airplane is one of my favorites and among the most rewarding, as they patiently applied problem solving, research and invention approaches without any formal training. An inspiring, and well illustrated, read is How We Invented The Airplane by Orville Wright.

February 14, 2017

The Dance of the Possible

I’m excited to announce my next book. It’s called The Dance of the Possible.

I’m excited to announce my next book. It’s called The Dance of the Possible.

This short, fast paced, irreverent guide to creativity is meant for anyone who wants to discover better ideas and finish projects based on them. In 21 short chapters the book offers a fresh and fun way to understand creative thinking, how ideas work, and insights from decades of study on both more productive and creative at the same time.

The book’s official launch day is March 15th. You can pre-order the book on kindle (print pre-order coming soon). And if you’re on my mailing list you’ll get a digital copy of the book for free before the rest of the world.

Early praise for The Dance of the Possible:

“You’ll find a lot to steal from this short, inspiring guide to being creative. Made me want to get up and make stuff!” – Austin Kleon, author of How To Steal Like An Artist

“A fun, funny, no-BS guide to finding new ideas and finishing them. Instantly useful.” — Ramez Naam, author of the Nexus Trilogy

“Concisely debunks all kinds of misconceptions about the creative process in a book that’s no-nonsense, fun, and inspiring.” — Mason Currey, author of Daily Rituals: How Artists Work

“This book will undoubtedly increase your abilities to invent, innovate, inspire, and make things that matter. It’s fun, it’s funny, and it’s phenomenally effective.” – Jane McGonigal, author of the New York Times bestsellers Reality is Broken and SuperBetter

“Highly recommended for anyone whose employment just might depend on the quality of their next idea.” – Todd Henry, author of The Accidental Creative

“Creativity is the nature of the mind. It is our birthright and our gift. The Dance of the Possible, beautifully, reminds us of how to open it.” – Sunni Brown, author of Gamestorming and The Doodle Revolution

“A fun read and a helpful book! Berkun demystifies creativity in work and play with nuggets of truth and common sense.”

– Dan Boyarksi, Professor, School of Design, Carnegie Mellon University

“This new nugget of genius from Scott is the best thing I’ve read about creativity in a long time.” – Dan Roam, author of The Back of The Napkin and Draw To Win

“This short, irreverent-yet-authoritative book from Scott will set you on the right path to get inspired and take action on what you create.” – Chris Guillebeau, NYT bestselling author of The $100 Startup and host of Side Hustle School

“…makes the font of creativity something that is right at your door, offering you a cup and inviting you to drink every day.” – Andrew McMasters, Founder and Artistic Director, Jet City Improv

“A spirited and tangibly useful guide to actually getting art done — memorably clear, mercifully artspeak-free, and filled with pithy nuggets of real-world wisdom.” — Ted Orland, co-author of Art & Fear.

“The best short book on creativity yet! Playful, irreverent, insightful, exciting! Full of good advice delivered by example rather than description. Get on with it, Berkun advises, and expeditiously gets you on your way!” – Bob Root-Bernstein, co-author of Sparks of Genius, Professor of Physiology, Michigan State University

“Decades of creative experience distilled into an efficient little book you can finish on a plane ride.” – Kirby Ferguson, filmmaker, Everything is a Remix

January 17, 2017

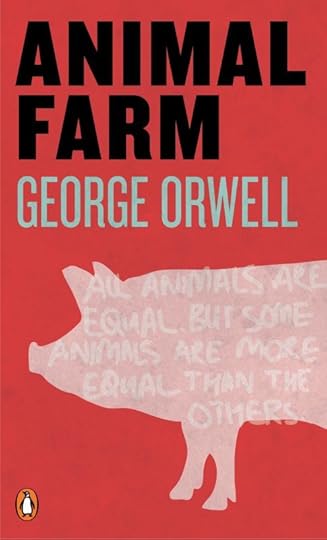

Orwell’s Animal Farm – Book Review

I’ve read Orwell’s Animal Farm three times now: once was in high school when I wasn’t paying attention, another was in my 20s when I felt I owed it a second chance and then again this week as part of an inquiry into what’s happening in the world. While it’s well known that the context Orwell was thinking of for the story was the Russian revolution, many themes resonated with the America and world I find myself in today. I’m also embarrassed to admit that for all this time I never knew that Pink Floyd’s Animals album was largely inspired by Orwell’s Book. Live and learn.

I’ve read Orwell’s Animal Farm three times now: once was in high school when I wasn’t paying attention, another was in my 20s when I felt I owed it a second chance and then again this week as part of an inquiry into what’s happening in the world. While it’s well known that the context Orwell was thinking of for the story was the Russian revolution, many themes resonated with the America and world I find myself in today. I’m also embarrassed to admit that for all this time I never knew that Pink Floyd’s Animals album was largely inspired by Orwell’s Book. Live and learn.

The insight of the book, beyond the allegorical fun of comparing people to animals, is its encapsulation of the nature of power. In this regard the book reminded me of Lord of The Flies, where little by little the assumptions about human nature are stripped away and what is left is surprising, true and terrifying all at once. By using a fairy tale it’s easy to keep some distance from what happens in Animal farm, after all it’s just a bunch of animals, but at the same time any reader understands that this is an allegory, and it’s making commentary about us all along.

The biggest surprise in this reading of the book was the gentle the slope of moral decay. Somehow we imagine that big changes come in waves, as popular history talks of revolutions and wars as sudden, dramatic events. But in Animal Farm as each layer of morality is stripped away it happens so slowly and naturally that it’s comprehendible some wouldn’t notice it at all. Or could easily choose to ignore it out of denial, stupidity, indifference or (increasingly) fear. Unless there are opposing forces successfully working against denial and indifference, what hope could there be?

I found myself asking how can it be so easy to separate the spirit of the law from the letter of the law? But then I think of the history of religion and mass movements, or debates about the 2nd amendment (where smart people on all sides have entirely opposing interpretations of the same handful of words) and know there are all too familiar patterns, dark ones, at work here. Somehow in the world of Animal Farm there are always good reasons for bad things happening, since the only reasons you are allowed to hear are ones that come from those in power, and soon you are compelled to want to believe life isn’t so bad at all, as it’s less scary than the alternative.

Without giving the story away, here are some choice quotes from the book, which I hope you will read:

From the preface / appendix:

“revolutions only effect a radical improvement when the masses are alert and know how to chuck out their leaders as soon as the latter have done their job.”

“If one loves democracy, the argument runs, one must crush its enemies by no matter what means. And who are its enemies? It always appears that they are not only those who attack it openly and consciously, but those who ‘objectively’ endanger it by spreading mistaken doctrines. In other words, defending democracy involves destroying all independence of thought. This argument was used, for instance, to justify the Russian purges. The most ardent Russophile hardly believed that all of the victims were guilty of all the things they were accused of: but by holding heretical opinions they ‘objectively’ harmed the régime, and therefore it was quite right not only to massacre them but to discredit them by false accusations.”From the text:

“Man is the only creature that consumes without producing. He does not give milk, he does not lay eggs, he is too weak to pull the plough, he cannot run fast enough to catch rabbits. Yet he is lord of all the animals. He sets them to work, he gives back to them the bare minimum that will prevent them from starving, and the rest he keeps for himself.”“THE SEVEN COMMANDMENTS

Whatever goes upon two legs is an enemy.

Whatever goes upon four legs, or has wings, is a friend.

No animal shall wear clothes.

No animal shall sleep in a bed.

No animal shall drink alcohol.

No animal shall kill any other animal.

All animals are equal.”“A bird’s wing, comrades,’ he said, ‘is an organ of propulsion and not of manipulation. It should therefore be regarded as a leg. The distinguishing mark of Man is the hand, the instrument with which he does all his mischief.”

“The animals formed themselves into two factions under the slogans, ‘Vote for Snowball and the three-day week’ and ‘Vote for Napoleon and the full manger.’ Benjamin was the only animal who did not side with either faction. He refused to believe either that food would become more plentiful or that the windmill would save work. Windmill or no windmill, he said, life would go on as it had always gone on— that is, badly.”

“and it became necessary to elect a President. There was only one candidate.”

Related:

The True Believer, review

Brave New World, review

January 10, 2017

Hidden Insight and The Third Donkey

There is a viral video making the rounds of several donkeys at an animal sanctuary trying to work their way out of a pen. Most people, including a writer at the Huffington Post, focus on the superior problem solving skills of the third donkey, named Oreste, who took a novel approach to finding his way out. Unlike Pedro and Domenico who choose to jump, he finds a more creative solution.

But there are three common mistakes of thinking about problem solving made here. Yes, I know it’s a cute video and it’s daft to read much into them. However these traps are common in daily life and how we think about problems and solutions.

Insight is defined as the capacity to discern the true nature of a situation. And we presume Oreste is the most insightful. But he benefited from the information gleaned by watching the first two donkeys (Pedro and Domenico). He was able to observe, and smell, the choices the other donkeys made. At first he tries to copy what they did, but then decides, for some reason, to do something different. But if he didn’t have the data he gleaned from the other donkeys he might have simply done what they did. Oreste appears to take the most time to study before he acts than any other donkey. This suggests more data + more time often leads to better solutions.

We ignore the behavior of the forth and last donkey. He doesn’t even get mentioned in the sanctuary’s own report of the event. But he might be the wisest of all. By doing the least work, he enjoyed the best outcome of all three previous donkeys at no expense of effort or possible embarrassment. There is an evolutionary advantage in being cautious. Most of the time in life we are more like the forth donkey than any of the others. We are evolutionarily motivated to wait and observe, conversing calories, until we’re forced to make choices or good choices become obvious.

The first donkey to leave gets no credit either. Arguably it’s Pedro who is the leader here, making the choice to be the first to leave. He takes the greatest initiative in deciding on this goal and acting on it by himself. But we are easily distracted away from his brave act by the novelty of Oreste’s solution, even though the outcome for all of the donkeys (leaving the pen) is mostly the same.

Our minds are biased towards simply narratives. We instinctively focus on the moment when something interesting happens, ignoring the sequence of events that led to that moment, and often ignoring the more interesting observations of what happens after the obviously interesting moment occurs.

There is an endless debate of strategy about whether it’s best to be the first with an idea, or to follow behind as a “free rider” and take advantage of the costs the first mover had to spend. There is no simple answer to this question of strategy, just as there is no single simple lesson to learn from watching donkeys escape from a pen.

December 5, 2016

2016 Post-Election Sanity Guide

For three weeks I worked hard to put the 2016 election in some kind of context. I read selections from history. I worked through all the commentary. I even went back and read some of the Constitution.

The result is this carefully researched 10 minute read that explains what happened, what it means and what you can do if you are concerned about the impact of a Trump presidency.

2016 POST-ELECTION SANITY GUIDE

November 22, 2016

Eight lessons from Nazi Propaganda

On my way through Austin, Texas last week I had a free afternoon and on a whim went to the Bullock museum of Texas History. To my surprise there was an entire exhibition about Nazi Propaganda, called State of Deception. It’s seemed timely somehow, so I bought a ticket and stepped inside.

Here is what I learned, in eight points.

Germany, as a democracy, was a world leader in the 1920s in media and mass communication technology. It had more newspapers (4700) than most nations in the world. It pioneered improvements to radio and television, the high-tech of the era. Its internationally acclaimed film industry ranked among the world’s largest. It was a technological and communication leader on the planet.

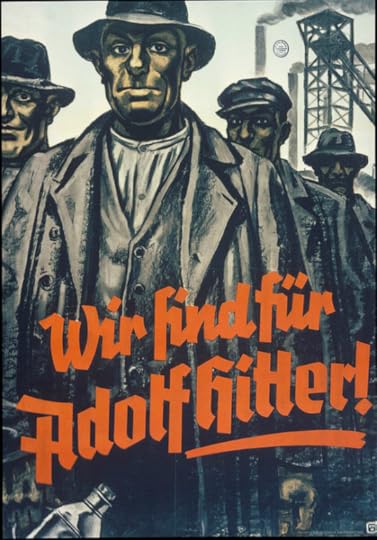

After the great depression (1929), German citizens were divided between left and right. Millions found the simple messages of Nazi propaganda appealing in times of economic hardship and instability. They left mainstream parties to support Adolf Hitler.

The Nazis’ platform did not initially scare many voters. While many voters weren’t necessarily at first attracted primarily to racist themes, they were willing to overlook them in hopes of economic promises. The Nazi’s carefully crafted different messages to different audiences, using nuance to signal to their deepest supporters without offending more moderate voters. This poster at right (“We’re for Adolf Hitler”) was aimed at unemployed coal miners, suggesting a vote for Hitler would bring their jobs back. At the same time explicitly racist posters were also being widely distributed.

The Nazis’ platform did not initially scare many voters. While many voters weren’t necessarily at first attracted primarily to racist themes, they were willing to overlook them in hopes of economic promises. The Nazi’s carefully crafted different messages to different audiences, using nuance to signal to their deepest supporters without offending more moderate voters. This poster at right (“We’re for Adolf Hitler”) was aimed at unemployed coal miners, suggesting a vote for Hitler would bring their jobs back. At the same time explicitly racist posters were also being widely distributed.The term propaganda was originally a neutral term for the dissemination of information in favor of a cause. In the 1900s the term took on a negative meaning “representing the intentional dissemination of often false, but certainly compelling claims to support or justify political actions or ideologies” (wikipedia).

Propaganda, by definition: plays on emotions over facts and mixes truths, half-truths and lies. Hitler, and his propaganda minister Goebbels, had a deep understanding of mass media. They masterfully offered an appealing message of national unity and a utopian future, while simultaneously targeting the brutal persecution of minorities and anyone who disagreed with, or competed against, their ambitions for power. Outsiders and minorities were an easy target to blame for national problems, or the failure to fix them.

In 1933 a fire at the parliament was used as an excuse to suspend the German Constitution. The fire was claimed to be the beginning of a communist revolution, allowing Hitler, only chairman at the time, to convince the president to use article 48 to suspend many elements of democratic process, giving the president near dictatorial powers. These powers were never released.

Within months the Nazi regime destroyed the country’s free press. There were no longer alternatives to propaganda, making it harder to recognize. The regime closed opposition newspapers, forced Jewish-owned publishing companies to sell to non-Jews, and secretly took over established periodicals. By controlling the media there was no possibility of dissension. Questions could not be asked. Answers could not be heard. Citizens were not offered alternative views to consider nor the means to voice them. Power became unchecked. Challengers were increasingly easy to threaten, as news of their challenge, or imprisonment, would never be known.

In less than six months, Germany’s democracy was destroyed. The government became a single party dictatorship. Rights such as freedoms of expression, press, and assembly were revoked. Police established concentration camps to imprison those deemed to be “enemies of the state” which included intellectuals, teachers, writers and artists, among those chosen simply because of their race or ethnicity.

An online version of the exhibit can be found here including a powerful archive of posters, signs and cartoons from the era as well as recommendations for supporting independent media in the US.

November 1, 2016

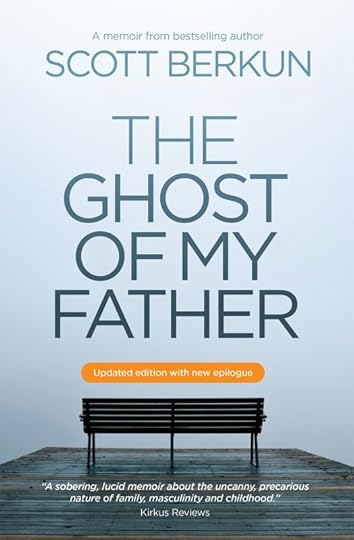

New Release: Updated Edition of The Ghost of My Father

I’m  proud to announce the new edition of The Ghost of My Father, with a new epilogue, is now on sale.

proud to announce the new edition of The Ghost of My Father, with a new epilogue, is now on sale.

The book was first released October 2014, and a year later my father died. The new epilogue explains what happened between these two pivotal moments in my life. It shares what he thought of the book (he did read it and shared his opinion) and what happened between us before he passed away.

This new edition includes a list of resources and recommendations for readers who want to explore their own stories, advice on writing your own memoir, plus an annotated list of books on family dynamics and how to learn from our past.

On Wednesday 11/2 (tomorrow) the book will be free on Kindle for 24 hours, in part to give folks who already have the book a chance to grab the new edition without having to pay for the whole thing. Please help spread the word to friends and family you know would benefit from reading my story.

“Bestselling author @berkun’s Ghost of My Father is free on #kindle tomorrow: #markyourcaledar”

Thanks again to everyone who helped support the first edition of the book.

Reviews from the first edition:

“A sobering, lucid memoir about the uncanny, precarious nature of family, masculinity and childhood.” -Kirkus Reviews

“Not only captivating, but also insightful… digs deep into many themes; family dynamics, forgiveness, grace, legacy, hope…” – Jen Moff, Thejenmoff.com

“Ghost of My Father is a poignant example of the value of positive role models. ” – Amy Mack, CEO of Big Brothers Big Sisters of Puget Sound

“…A brutally honest memoir, well worth reading.” – David M. Allen M.D., Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry, University of Tennessee

“compelling… ideally suited to an audience that’s similarly concerned with the challenges of adulthood and parenthood in the 21st century.” – Kirkus Reviews

“Thought-provoking read, and highly recommended” – Thomas Duff

“When I finished it, I felt more human and less alone.” – Heather Bussing

“Finished in one intense sitting. Intensely personal & gripping” – Michael van Lohuizen

Get The Ghost of My Father updated edition.

October 24, 2016

Notes from Leading Design 2016

I’m attending the first Leading Design event in London, hosted by Clearleft. I spoke first about Design vs. The World (PDF) and I’ll be adding notes to this post as the event goes on. Please forgive typos – I’ll come back and clean up when I can.

Farrah Bostic, CX is the CEO’s Job

She romped through the history of business schools in the U.S. and noted that it was Selfridge who coined the irritating term “the customer is always right” (1909). She critiqued Taylorism (1911), and the management centric philosophy he had “Managers are inherently smarter than workers”. She also disputed the Ford quote about “if I asked people what they wanted. He didn’t invent the assembly line but did employee it successfully at scale.

Ford did actually say “If there is any one secret to success it lies in the ability to get the other person’s point of view and see things from that person’s angle as well as your own.”

She emphasized how Schumpeter’s concept of creative destruction is central to startup culture today:” we must harness change otherwise it will drown you”

Next she referenced Drucker who posed in 1954: “The purpose of a business is to create a customer, the business enterprise has two – basic functions: marketing and innovation.. all the rest are costs.”

Today it’s common for people to confuse principles with processes – for example you don’t “do lean” you “think Lean”.

Another customer value model is the Toyota production principles:

precisely specify value

identify the value stream for each product

make value flow without interruption

let customer pull value from producer

and pursue perfection

A disturbing (or exciting) fact is that Fortune 500 companies last shorter than ever. And yet CEOs get paid more than ever (and tenure is shorter, 6 years on average). Worker income stays the same.

Many famed books that claim theories to explain why some businesses last don’t hold up over time. She suggested we “Read books and then wait 5 years and see how well the theories hold up” – Good To Great is a good book, but many of the highlighted companies have not lasted.

A common mistake CEOs make is to spend more time talking to their best customers rather than their next customers. The American TV show Undercover boss is predicated on an essential truth: often the CEO has no idea what is going on in the company.

“FOMO leads to dalliances not marriages”

“Malcolm Gladwell effect: CEOs go to a party and hear about a book and get FOMO so they fall for the latest trends and are prone to hiring consultants who sell the latest trends and buzzwords (offered my Eric Reis)

“The data will tell us what to do” is a myth –as if a magic voice can speak to you off camera with the secret truth.

Recommendations:

Uncover your riskiest assumption

Get to know your next customer

Commit to change (air cover and ground cover)

Make ruthless sacrifices (jettison old business and people who don’t fit the new vision)

Gail Swanson, How to present to decision makers

“Some ideas are so stupid that only intellectuals believe them” – George Orwell

We tend to believe “If we have the best rationale for why we made a design decision that will make it easy for decision makers” – but this doesn’t work very well

Design is change – FUD fear uncertainty and doubt. Designers enjoy it, it is our business but we have trouble empathizing with people who don’t.

Human Centered Change is a good way to think of what we do and Behavioral science can help us. But one presentation is never enough to create influence– it’s a series of points of communication in sequence that creates influence

Your Role

Rebel – I made something and the world should change

Organizer

Helper – facilitate discussion

Advocate – create a belief and partnership

When most designers show their work in presentations they are asking “Is this good” – this is non productive. You are asking someone to check your homework and give you a grade. It’s best to skip this and focus instead on “Is it right for you? For this situation/scenario?”. You are a professional and should stand behind your work.

How to you build an effective presentation:

Who is in the room?

What is their POV?

What background do they come from?

Are the business focused? Service? In-house?

What are their pressures?

What forces are acting upon them?

How are they rewarded?

A good framing question is to think about: We can get A to do B if they believe __________________ .

A narrative endows information with meaning. Giving data points doesn’t help decision making – it leaves interpretation to them. Part of our job is to provide the story and framework for interpreting data.

Lead a conversation about risk. “What is the risk if we are wrong?” – often it’s something that can be anticipated and made less scary.

The work to create the design is as valuable as the design itself. It helps to answer questions, test and validate assumptions.

Tactical language (vebal judo book)

Build common ground

Strip phrases: “I appreciate that… but” “I understand that concern but we can address it if we…”

Paraphrase – people rarely say what they mean. Ask clarifying questions.

What is the experience of you? Are you protecting yourself by being an expert? Are you pompous? Or are you connecting with them and do they see you as an ally?

Sarah B. Nelson, A Place of Our Own: Making Networks Where Design Thrives

“Why is it that some projects succeed and some fail, even when it’s the same group of people” – question she’s obsessed about . She learned a great deal by trial and error and making mistakes, as we all usually do.

IBM where she works is huge. But it’s easier to scale down than to scale up, and her lessons should be easy to apply. IBM 350k employees. Founded in 1905. Definitely Big and Old. She works on thinking about what makes great creative environments.

She asked people in design studios why they were great places to work and these were some of their answers:

You can work alone or together

Ideas and knowledge are shared

My imagination is nurtured

Everyone is pushing each other to be best selves

I can draw on the walls

People can collaborate regardless of their role

She asked the audience about the size of the teams and explained there are very different challenges at different sizes.

Team of 5 (Magic Number)

small team

information flows freely

you know what each other does and is working on

Team of 11 (size of family unit – enough people to spread work, but few enough to have deep relationships) subgroups

light processes

someone dedicated to process

still visible knowledge

Team of 20

emerging specializiation

Team of 35

systems starts to break down

suddenly everyone can’t be involved in all decisions

Team of 70

people who like small environments slip away

system breakdown

Team of 150

Dunbar number

GoreTex organizes company in business units of 150 people – buildings and parking lots only hold 150 people. When the parking lot gets full, they build another building. Merit based flat system.

The basic needs of creative environments are the same regardless of the size.

What to do?

Establish standards and tools

Provide paths, shortcuts and guides

Empower designers and leaders

Enabling conditions

Social environment – strong relationships, sense of belonging, diversity, empowered ownership, dependability

Physical environment – Flexibility, support visual thinking, enabling technology, abundant materials

Emotional environment – Stability and Safety, growth mindset, how safe is it to fail in public, is critique useful or ego driven, respect (attrition is caused here)

Intellectual environment – stretch goals, new ideas invited, cross-pollination, knowledge sharing

People + Practices + Places = Outcomes (ibm.com/design)

What can you do?

Establish standards and tools

Provide paths, shortcuts and guides

Empower designers and leaders

Andrea Mignolo, New on the Job: Your First 90 Days in a Design Leadership Role

As a design leader you are responsible for being a design ambasaor and to build design into the DNA of the company. She examined different leaders from Game of Thrones and asked the audience if we thought they were good or bad managers (Jon Snow / Jofree).

Authentic leadership – built on ethical foundations. Takes a lifetime of practice (principles aren’t necessarily easy to practice)

For four years she lead a 40 person guild in World of Warcraft. The other leaders had different styles and they wondered if love or fear were been ways to lead. And they experimented to see which work best – they found they call all work if the match your style.

Good design & good leadership share many traits. They are both: thoughtful , serve people, appropriate, empathy, intentional, vision, collaborate

“Designers can not design a solution to a disagreement” – Montiero

Harley Earl was a designer at GM –”My primary purpose for twenty eight year has been to length and lower…” His north star, or guiding idea, was to make GM cars more natural and oblong in shape.

What is your vision for design, what do you believe, what is your north star?

What is your company’s north star?

What different is it from yours?

How can you minimize the delta?

What did you learn in your interview?

When starting a new thing 30/60/90 days are arbitrary units of time for thinking about transitions to new things. Instead she offered a more useful one: 10/10/40/30.

The First 10/10/40/30 – Is the pregame. You are trying to gain clarity and information. Take your north star and apply it.

But apply it to the context of the “layer cake” of your world:

Board of directors

executive team

company

design team

colleagues

departments

public

parent

During pregame, connect early and socially with as many people as you can. Do sleuthing about your predecessors and what history there is that defines perception of your role

10/10/40/30 – Critical 10

Rigorous planning is the best prep for improvisation, Expect the plan not to work as planned, but to have developed it will help you deal will all of the situations you couldn’t have possibly planned for.

Think about how you want to be perceived and invest in it. She chose Optimisit, Open, Awesomely competent. Think about your origin story, which you will be asked about often. It helps shape how you are percieved. Good origin stories: why you do what you do, other organizations you worked in, and why you are excited for your new role.

Boatload of meetings. Take notes and have beginners mind. Write down jargon and abbreviations (and ask for clarification later). Look for allies – people who care about design. They may not use design language but there are giveaways. Dev who spends extra hour on details. Marketing who emphasized brand.

Talk to people in different departments to ask: how they see design, how design can help them.

10/10/40/30 – Making Moves

Formula for Trust: (Credibility + reliability + intimacy) / self-orientation

Earl’s design studio at GM. When he joined the company his department was called the beauty parlor and his team the pretty boys. As their reputation improved people wanted to visit the studio – it was a cool place to be. It made design visible (externalized) and helped establish credibility.

Foundations

Pre game

Critical 10

Making moves

To infinity and beyond

As a leader, it’s Education, inspiration and facilitation core skills.

Buy in

Credibility

Trust

Communication

Ah-ha moments (and ha ha moments)

Julia Whitney, Culture, culture, culture: tales from BBC UX&D

She shared a story of Rupert, an engineer, discovered a problem with a mixing board used for live production in the BBC. It was a difficult scramble but he dropped everything else to fix the problem and solved it before any listener noticed.

Later, In an offhand meeting, she mentioned an idea for consolidating how their clunky wifi worked. A few weeks later a set of wireframes came back with an overdesigned and misunderstood set of requirements. This reflected something about BBC engineering culture – they had the habit of dropping everything, respond to a crisis, and fix the problem quickly, but without clarifying or communicating well.

“[Culture is a] shared set of unconscious assumptions as it solves their problems ” – Edgar Shein

One way to better understand a culture is to ask: what counts as heroic behavior in this culture? That’s what helps explain Rupert’s behavior.

What levers does a leader have to influence culture? She offered two kinds.

Structural methods

Embedding mechanism (leadership behaviors)

BBC (where she used to work) is structured in genre silos (news, sports, etc.) UX was organized in the same way. Design became increasingly divorced from development. Churn escalated. When she took over the leadership of the group, she admits she brought her own cultural assumptions. Eventually they arrived at a functioning model called federated ? )

In 5 Dysfunctions of a Team, it’s explained that there are five layers that contributed to teams that function well:

Trust – I can give my true opinion with repercussions

Conflict –

Commitment –

Accountability –

Results –

Regarding conflict – she realized we were being way too nice to each other and were unwilling to disagree. This kept information off the table and kept commitment from being heartfelt. Our decisions were too wishy-washy. “Fuckmuttering: is the complaining you do outside of a meeting to vent your true feelings”

The invented the term Productive Ideological Conflict – useful conflict that is explored until a resolution is reached.

Conflict mining: agreeing to dig in to conflicts rather than avoid them.

Motto “We will not prioritize relief over resolution”

Shein also suggested that unless leaders can acknowledge their own vulnerabilities transformational learning can not take place.

Q: “What changes in your behavior does the culture you are trying to build require from you?”

October 13, 2016

Notes from Digital PM Summit 2016

I’m the closing speaker today at Digital PM Summit in San Antonio, TX, and I’ll be taking notes (or in fancy terms, liveblogging) for every session that I sit in until it’s my turn. I’ll be following the basic rules of Min/Max note taking and will update this post as the day goes on. It’s the first PM event I’ve been to in years – brings back many memories from my first career.

Please forgive typos, I’ll get to them when I can. Here we go!

1. Brett Harned – Army of Awesome (slides)

Brett, one of the organizers of PM Summit, asked the audience how many people became Project Managers / Producers on purpose, vs. how many fell into it accidentally, and most of the room raised their hands as accidental! (He joked with a slide that said “You are not an accident” :) This isn’t a surprise as often the role evolves as a project or organization gets larger.

It’s also a related observation that most people don’t know what a project manager does, particularly digital project managers. Once during a trip he was stopped by a UK immigration officer who seemed baffled by his job title and asked: “what kind of projects do you manage then?” He shared a list of quotes from colleages who he asked to explain what he did for a living:

“As far as I can tell project managers do nothing, but if they stopped I’m pretty sure everything would fall apart” – Paul Boag

“You help teas organize their work” – Brett’s Mom

“Project management is like sweeping up after the elephants, only less glamorous” – @zeldman #dpm2016

He shared how the History of Project Management goes back at least 4000 years, and that there’s a long history of teams of people making difficult things. But that digital project managers have yet to be entered into that history in a meaningful way, and part of what he’d like to see is greater recognition for the contributions digital project managers make.

7 DPM (Digital Project Manager) Principles: The balance of his talk was an exploration of 7 principles about leading teams and projects.

Chaos Junkies – we thrive on problems because we know we can solve them. We break processes to make new ones. We make our own templates. We managed with our minds, not our tools.

Multilingual communicators – listen and take cues from our team and clients.

Loveable hardasses – reputation for being firm but wise and well intentioned.

Consumate learners and teachers – that teaching teammates helps the project, the organization and the pm

Laser focused

Honest Always – cultivate a reputation for straight talk

Pathfinders – do more than take care of budget and timeline

His final question for the audience was: where will you take us? Which principles resonate the most?

2. Natalie Warnert – Show Me the MVP!

The core of her talk was about the concept of MVP, or Minimum Viable Product, and how to apply it to projects. She referenced Eric Reis’ book, The Lean Startup, and asked who had read the book: I was surprised how few hands went up. Perhaps I’ve been to too many start up events the last few years. I had a hard time following the thread of her talk – she referenced many models and frameworks but it was tough to find salience to pm situations, or connections to each other.

She offered four goals or objectives:

Building just enough to learn

Learning not optimizing

Find a plan that works before running out of resources

Provide enough value to justify charging

She mentioned loop models, were you have a cycle of behaviors you repeat, such as: Think -> Make -> Check. Briefly she touched on Lean UX, and how customers must be involved as part of that check process – “Customers don’t care about your solution, they care about their problem”.

Next she talked about metrics, and offered this quote: “A startup can only focus on one metric and ignore everything else” – Noah Kagan. I didn’t agree with this, as it sounded more more like hyperbole than sanity – plenty of successful startups have focused on multiple metrics, or at least prioritized them.

She offered “Pirate” metrics as good choices for what the primary metric should be:

Acquisition

Activation

Retention

Revenue

Referral

Regarding building software, she explained the Build Model:

There are 3 desirable criteria, but you rarely can do all three

Build right thing

Build it fast

Build thing right

(reminds me of “you can have fast, cheap or good: pick two”)

Which she compared to the Learning Model (Learning, Speed, Focus), but I didn’t quite understand how they related to each other.

Lastly she provided this outline, in reference to a project she managed:

Reduce scope

shorten time to feedback

get out of the deliverables business

learn from customer behavior