Scott Berkun's Blog, page 7

March 6, 2018

The proof that we’re all creative: losing your keys

On Tuesdays I write about the top voted question on Ask Berkun (see the lovely archive). This week’s question is from Crysel [44 votes]:

What is the real motivation for creativity?

For most of history people did not use the word creativity very much. They just invented and discovered things in the course of their lives without applying special labels to them. But something strange happened to in modern times. We developed a romance around the notion of creativity. Most people today think of it as an extra layer of cognitive powers, that only special people have. This is untrue and there’s an easy way to prove it.

Imagine you are an ordinary person of average intelligence (some of you will have to do more imagining here than others). You get ready to go to work and you stop at your door to do your pre-airlock check for your phone, your wallet and your keys. You realize your keys aren’t in your pocket. Oh no! And at this moment an important sequence of cognitive events takes place.

Your brain instinctively tells you to look by the door in the place where you usually put your keys when you come home. So you go and look, perhaps at the basket on the shelf right by the door where they usually go. And they are not there!

Now your brain thinks a bit more. Maybe they fell? So you check on the floor and behind the basket. Not there!

And here is where the magic starts: your brain starts getting increasingly creative. You look under the basket. You look in the hallway outside. You look in clothes you haven’t worn in days, or weeks. Then you check the basket again (perhaps the keys magically reappeared since the last time you looked?).

You consider increasingly unusual explanations for where your keys are. Maybe you left them at the restaurant last night (which is unlikely since you got into your apartment)? Or someone broke into your place and stole them! (which also doesn’t make sense as if they broke in they don’t need your keys). And on and on your brain will go inventing and trying out solutions.

The lesson here is that when suitably motivated your brain will be creative all on its own. During step 3 above you did not have to engage in a brainstorming exercise or put on a magic hat of ideation. Your mind will, when motivated and presented with a hard problem, generate inventive, unusual and unorthodox ideas. This helps explain why our species has survived despite not being very strong or very fast. We are good at solving problems and when we are motivated can persist in trying to solve even very hard ones.

Now some people hear this and say that looking in strange places for keys isn’t really creative because most of those ideas are failures. But that’s just it. Creative work is very much like looking for keys. You have to do the work to explore many alternatives, many of them unsuccessful, until you arrive at a worthy idea. Even the most brilliant writers and artists write first drafts and draw early sketches that they eventually throw away. They learn much from those “failed” ideas and those lessons help make their second, third and final drafts better than the last. Working with ideas is never an efficient process. It’s messy and uncertain no matter how talented you are.

All this means that when we don’t feel creative often all that’s missing is a strong enough motivator. Sometimes we have demotivators in our own minds, like fear of being judged by others or fear of failure and it’s only by becoming more self-aware that our natural creativity can be free to surface. Other times we’re in cultures or teams that penalize creative thinking. But even in the best situations remember that creativity is a kind of work. You have to burn extra calories. And most of the time we, and our brains, prefer to be efficient and do the least amount of work necessary. But when we are suitably motivated, perhaps out of fear (losing your keys) or passion (solving a problem you care about deeply), our brains have most of the tools we need already built in.

References:

Thanks to George Carlin and his ‘losing things’ riff

This essay is one of the many lessons from my latest book, The Dance of the Possible: the mostly honest completely irreverent guide to creativity. So if you liked this essay you should check out the book.

February 27, 2018

Are engineers more creative than designers?

On Tuesdays I write about the top voted question on Ask Berkun (see the lovely archive). This week’s question came via email from Pavel Pavia [43 votes]:

Are engineers more creative than designers?

Both answers (“Yes they are!” and “No they are not!”) are naive. It’s a minefield to compare massive groups of people against each other especially around a sloppy word like creativity. We all likely know some engineers who are very creative and some who are not. We also know some designers who are very creative and some who are not. I can’t even imagine trying to average them out into two neat little piles and have the resulting comparison be of much use. But what then? Why can’t we have some fun? ok – FINE.

Let’s start by ditching the word creative. It’s a romantic word and the wrong one. When someone hires an engineer or a designer they want a problem to be solved. The creative ability we’re talking about is to develop ideas that solve problems into working solutions. Do good engineers and designers both do this? YES. They might be different kinds of problems, and they may use different tools, but both show up at work with the intent to problem solve, not “problem create’ or “problem multiply” (although such people do seem to exist, unfortunately).

The first argument is usually an anecdote about how “all the designers/engineers I’ve worked with suck” and to that I say you might be right. You’ve probably never worked in a healthy, successful organization that respected both roles and hired talented people to play them. But they’ve always existed – look at the teams that made the best products you admire and I bet there was a team of both excellent engineers and designers working together. Until recently it was only in elite companies that these investments were made, but that’s changing.

The next argument is often someone pointing out that designers are really just planners, since they can’t actually build their plans themselves. They need an engineer to go and built it. But so what? Why is the ability to build something necessarily superior to the ability to conceive the plan? It might be superior, but it might be inferior. I don’t think Beethoven could play the trombone, but he could write the plan for what they (and dozens of other instruments) should do, and that’s why we know his name and not his trombone player.

But I’m not taking sides here. Not really. To succeed at solving problems you need both the plan and the ability to build it. The hard part is that depending on what the problem is, it can be either conceiving the plan or the ability to build it that is more difficult. And people are bad at recognizing when the most important challenge is in a domain that isn’t theirs (“If you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail”). Engineers are notorious for dismissing designers because of their own ignorance of what the customer’s true situation is (and the related potency of the designer’s plans), and designers are notorious for dismissing engineers because of their own ignorance of what the engineering constraints truly are.

The running sardonic joke in all this is designers and engineers tend to share more personality traits than not. Which include:

Passion for aesthetics (debates on visual style mirror debates on code style)

Preference for control (engineers love their control over bits similarly to how designers love control over pixels)

Reverence/Arrogance for idea purity (that there is a right way to do certain things)

A desire to make great things that help people

Which means many of the conflicts between designers and engineers are about bad management, the lack of a leader providing shared goals that unify these traits towards a common cause. Both trades are about problem-solving and when motivated can help each other with their individual tasks. Framed properly, and properly motivated, designers can have insights that help solve engineering problems and vice versa. All that’s required is some respect, shared goals and a curiosity to discover other ways to approach solving problems.

It’s useful to go back to a time when the distinction between designing something and engineering something didn’t exist. For most of the history of invention, people did it all themselves. When Archimedes or Archytas invented the screw (which is a mind-boggling act of genius), was he designing or engineering? Would anyone at the time have cared in the slightest what label was given? John Roebling, the architect of the Brooklyn Bridge, knew that to make something great required both great engineering and great design. He couldn’t build a beautiful, functional, enduring bridge without them both. He and his team would switch between thinking more like designers and more like engineers whenever necessary, as they were unconstrained by the strict delineations we’ve created for ourselves in modern times, and we should all consider doing the same.

Related:

Programmers, designers and the Brooklyn Bridge

[Note: Pavel’s actual question was “What is the reason for which we believe that the people who dedicate to the arts are more creative than the engineers?” but as I wrote an answer it morphed into a simpler question.]

February 22, 2018

Has Your Boss Set You Up To Succeed or Fail?

On Tuesdays I write about the top voted question on Ask Berkun (see the lovely archive). Yes I know it’s Thursday, but better late than never. Here’s this week’s question:

I have a new boss who I don’t trust yet. How can I make sure they’re looking out for me?

The term “set up to succeed” means a person has been given most of what they need to do their job well. A good boss does more than just set goals and give assignments: they should see themselves as responsible for ensuring good work happens (See: Lefferts Law of Management). First, they think through the steps that need to happen for someone to do a project and where the challenges are going to be. Second, they invest their own time clearing a path for those tasks to go more easily (so higher levels of performance are possible). A good boss builds a runway for you so that you can smoothly take off. Alternatively, you know you’re being set up to fail if you’re assigned a project with impossible odds, conflicting goals or a fraction of the resources required. When there are major obstacles on the runway, or no runway at all, your manager isn’t doing their job.

Here’s a simple list of questions you can ask to see how well set up you are to succeed (or fail). They can be used to structure a conversation with your boss about what you need and why.

Do I have the right skills? If you’re told to pilot a Boeing 747 but you have never even flown a paper airplane, whose fault is it if you fail? What training and mentoring is provided to help close skill gaps? Does your boss understand what you can and can not do as well as what the project requires?

Do I have the right resources (budget, staff)? You may have the right skills, but if you don’t have enough time or money to do the work, you’ll fail anyway. The goals of the project might need to change if the available resources can’t.

Are there clear goals (and non-goals)? Clarity on desired outcomes is one of the most important things a leader provides. Does everyone understand and agree on how you’ll know when the work is done and that it was done right? A non-goal is something that’s easily assumed to be a goal, but should be avoided.

Do the people you depend on have the motivation to help you? You may need several people to get work done before you can do yours. Will they prioritize your requests? Help make sure you have what you need? A good boss will have talked to other staff in the organization about your tasks and created an agreement for how you all will work together.

Are senior management’s goals aligned with the ones you have been given? Your odds of success are much higher if your individual goals line up with those around and above you. If they don’t, you’ll be working against the grain of your organization. A good boss has made sure the right senior staff know about your projects and that all the goals line up.

What roadblocks are in your way that you do not have the power or skills to resolve? Who has been made aware of them? Who has the power you need to resolve them? Has your boss worked with you on a plan? Have you warned the right people of what may happen if the roadblock is not cleared?

Incompetent managers often unintentionally set up their employees to fail. They don’t realize they are giving conflicting goals, poorly allocating resources or that they’re asking people to take on work that is politically sensitive and possibly damaging to their reputation. This means you have to advocate for yourself, first by thinking through the challenges you’re going to face and second by involving your boss in helping you clear them out of your way.

Of course, depending on the job you have, and how senior your role is, you may be expected to identify and solve many problems on your own. Some organizations call this “Dealing with Ambiguity” or “Organizational Agility” and think of it as a skill. It’s true that stronger employees can handle more challenges on their own. However, the reason why managers are paid more is that they have more responsibility and power for making good work happen. If they do nothing to help their staff succeed, they’re simply not doing their job.

What other ways have you seen managers set up their employees to succeed or fail? Leave a comment.

Related:

The Boss That’s Never There

How To Survive a Bad Manager

Has your boss set you up to succeed or fail?

On Tuesdays I write about the top voted question on Ask Berkun (see the lovely archive). Yes I know it’s Thursday, but better late than never. Here’s this week’s question:

I have a new boss who I don’t trust yet. How can I make sure they’re looking out for me?

The term “set up to succeed” means a person has been given most of what they need to do their job well. A good boss does more than just set goals and give assignments: they should see themselves as responsible for ensuring good work happens (See: Lefferts Law of Management). First, they think through the steps that need to happen for someone to do a project and where the challenges are going to be. Second, they invest their own time clearing a path for those tasks to go more easily (so higher levels of performance are possible). A good boss builds a runway for you so that you can smoothly take off. Alternatively, you know you’re being set up to fail if you’re assigned a project with impossible odds, conflicting goals or a fraction of the resources required. When there are major obstacles on the runway, or no runway at all, your manager isn’t doing their job.

Here’s a simple list of questions you can ask to see how well set up you are to succeed (or fail). They can be used to structure a conversation with your boss about what you need and why.

Do I have the right skills? If you’re told to pilot a Boeing 747 but have never flown even a paper airplane, whose fault is it if you fail? What training and mentoring is provided to help close skill gaps? Does your boss understand what you can and can not do as well as what the project requires?

Do I have the right resources (budget, staff)? You may have the right skills, but if you don’t have enough time or money to do the work, you’ll fail anyway. The goals of the project might need to change if the available resources can’t.

Are there clear goals (and non-goals)? Clarity on desired outcomes is one of the most important things a leader provides. Does everyone understand and agree on how you’ll know when the work is done and that it was done right? A non-goal is something that’s easily assumed to be a goal, but should be avoided.

Do the people you depend on have the motivation to help you? You may need several people to get work done before you can do yours. Will they prioritize your requests? Help make sure you have what you need? A good boss will have talked to other staff in the organization about your tasks and created an agreement for how you all will work together.

Are senior management’s goals aligned with the ones you have been given? Your odds of success are much higher if your individual goals line up with those around and above you. If they don’t, you’ll be working against the grain of your organization. A good boss has made sure the right senior staff know about your projects and that all the goals line up.

What roadblocks are in your way that you do not have the power or skills to resolve? Who has been made aware of them? Who has the power you need to resolve them? Has your boss worked with you on a plan? Have you warned the right people of what may happen if the roadblock is not cleared?

Incompetent managers often unintentionally set up their employees to fail. They don’t realize they are giving conflicting goals, poorly allocating resources or that they’re asking people to take on work that is politically sensitive and possibly damaging to their reputation. This means you have to advocate for yourself, first by thinking through the challenges you’re going to face and second by involving your boss in helping you clear them out of your way.

Of course, depending on the job you have, and how senior your role is, you may be expected to identify and solve many problems on your own. Some organizations call this “Dealing with Ambiguity” or “Organizational Agility” and think of it as a skill. It’s true that stronger employees can handle more challenges on their own. However, the reason why managers are paid more is that they have more responsibility and power for making good work happen. If they do nothing to help their staff succeed, they’re simply not doing their job.

What other ways have you seen managers set up their employees to succeed or fail? Leave a comment.

Related:

The Boss That’s Never There

How To Survive a Bad Manager

February 13, 2018

What makes a book a good read?

On Tuesdays I write about the top voted question on Ask Berkun (see the lovely archive). This week’s question came via email from Dennis S.:

What makes a book a good read?

Great question, but there’s no easy answer! Which is true for most great questions.

The simplest answer is “are they engaged enough to want to know what happens next instead of doing one of the 100 other interesting things in their lives they don’t have enough time for?” which sounds nice, but what engages one person can turn off another. Which is why there are so many genres, styles and types of books. For fun, go read the 1 star Amazon reviews for your favorite popular book. Many people hated it and couldn’t finish it! Does this mean the book is actually terrible? Maybe, it depends on your preferences and opinions. Art is highly subjective.

This fact is both wonderful and horrible. Wonderful because it means if you can find an audience for your particular approach to writing, you can be successful even if the rest of the world doesn’t like it. It’s horrible because success and what is good are entirely subjective which makes it easy to lose confidence, give up, or get distracted by looking for some mythical magic formula for “writing good books” which doesn’t exist. There are certainly good books on writing and story structure which are helpful, especially for new authors, but they’re more rough guides than step-by-step-magical-spells. Since books have no hidden parts, all the words are there on the page, it’s of great value to study books you and others think are good reads and ask “Why does this work the way that it does?”

It’s also useful to think what makes for a bad read. A bad read probably means:

The writer is very confused about what is interesting about their subject for the reader

The way sentences and paragraphs are constructed is confusing and hard to comprehend without reading them more than once

The book is organized poorly and it’s hard to understand why one story or chapter follows another

There is no momentum, emotional interest or curiosity created for the reader

Most serious writers have early readers who read drafts, give feedback, and help the writer understand what’s working in their current draft, and what it isn’t. They’re learning from actual readers which parts aren’t as strong as they think. All first drafts are bad. Many second drafts are too. The process of writing is rewriting and shaping material over many drafts into something good. A good read is usually the result of many revisions of a bad one.

Most serious writers also work with editors, particularly developmental editors who can guide and give advice broadly about what is working, or not, about each draft. The challenge is it’s hard to find people who give thorough and useful feedback beyond “I like it” or “I hate it”. You have to invest in finding good feedback givers, not to mention, being receptive to hearing things you don’t want to hear (which are probably true) and also being willing to make significant changes to a draft based on what you learned, rather than being stubborn or egotistical about it.

My favorite one link to give people about writing seriously is Jane Friedman’s website, filled with resources, references and recommendations.

February 6, 2018

Which is more dangerous: writing badly or reading poorly?

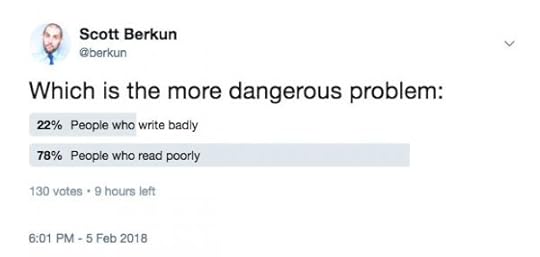

On Tuesdays I generally write about the top voted question on Ask Berkun (see the lovely archive). This week I turned the tables, and asked my followers on Twitter a simple question:

Which is more dangerous: people who write badly, or people who read poorly?

Polls like this are mostly just fun for me. Even so, I try to word them carefully and think through how to make the question less leading towards one answer. And then before I post it, I stop to think up a guess at what the results will be.

In this case I predicted it would be nearly even. I thought the poll was clever, but not particularly interesting as binary choices often create false dichotomies. I admit I was quite surprised to see the result (21% write badly, 79% read poorly):

Yes, it’s true that binary polls are often unfair as in any real-life decision there are layers of nuance, clarifications and details that change both how you might define the problem and how you’d try to solve it. But the brutality of the forced choice has a power too, at least as a thought experiment: if you could only solve one of the two problems, which would you solve?

I see now that I agree with the answer. Here’s why:

A bad reader can squander the work of a great writer. If the reader is only skimming headlines or reading primarily for speed rather than comprehension, it’s easy for them to misunderstand or overlook the value of what they read. Reading is always the last step and it takes place entirely in the reader’s mind, not the writer’s. And of course there are far more readers than writers as it only takes one writer to produce something, but hundreds or thousands of readers can read that one work.

Misinformation and fake news are popularized by readers. Our decision to share something on social media hinges on our (mis)comprehension of its accuracy, meaning or truthfulness, or our disregard for those things. What becomes a trend, goes viral or becomes popular is based entirely on readers opinions no matter how informed or uninformed they are, or how many great works from great writers have been entirely ignored.

Learning to read better helps you to write better. The most common and worthy advice from writing teachers is to become a better reader and to read better works. It’s by improving the questions you ask as a reader, and developing the patience to pause and think, to reconsider, to glance between the lines, that the capacity to write well begins to grow. If we want better writers, we need better readers first.

Now that you are finished reading what I have written, what comments will you write for me to read? I look forward to reading your thoughts with extreme generosity, thoughtfulness, and patience :)

(I tried to find a picture of dangerous reading, and this was the best rights-free image I could find. I mean, she could trip in the sand, or maybe a big rogue wave could come up a knock her over, right?)

January 30, 2018

Star Trek and the ideas we must reject to save our future

On Tuesdays, I write about the top voted question on Ask Berkun (see the lovely archive). This week’s question came from Ms. Unknown:

What ideas must we reject to save our future?

It’s wonderfully romantic to view the world from the point of view of a checklist of things we can either choose to accept or reject. I don’t mean this in a judgmental way. It really would be nice if we could vote each year as a planet on which ideas to promote or reduce, and then all collectively work hard towards that goal. But the tangible reality of how human society works regarding ideas is a terrible mess. Or at least, more positively speaking, it’s a complex web of interactions of needs, wants, scopes, fears, cultures, timings and coincidences. We’re all fighting our local crusades for more happiness or security and rarely have much reason to think in a unified way about what kinds of ideas are best or worst for all of us.

Ms. Unknown offered four ideas to reject: competition, scarcity, individualism, and the endless pursuit of more. Which in their way, in a simple list, seem lovely. She is describing the utopian world of Star Trek, where all core needs for all people (or at least human earthlings) are met. Star Trek of course conveniently skips over how they got from our primitive world to theirs. Even assuming Ms. Unknown is right, how do we get there? It’s hard to see it happening without a science fiction cliche like a terrible world war or alien invasion, something to force our myopic species to recognize our survival depends on our partnership in sharing spaceship earth and not petty self-interests, but I hope to see neither of those scenarios play out in my lifetime.

I’m prone to dualism, so I see most ideas on this list as having good and bad elements. Competition can be good if it’s done in a healthy way. Many people only do their best work if there is some element of competition, like artists, musicians or athletes who see others doing interesting work that challenges them to keep improving and growing, perhaps collaborating and building on each other’s work. But you can’t have a football league, or a literary society, with only one team or one author. Bad competition is when the combined choices by some competitors work against the greater good (Say, when two businesses collude to fix prices in a market so that no new entrants can even try to compete). This means it depends. The ideas aren’t necessarily good are bad, it’s how they are applied, with what goal and what result.

By scarcity, I assume she meant of fundamental needs like food, shelter and water. It’s hard to argue against the improvement of the standard of living for all. What’s there to lose for the rest of us? Probably not much. But taken to the other end of the spectrum, a question about the Star Trek Utopia is without scarcity of some kind, how are people motivated to strive? The history of America is driven by people from other nations who wanted a better life, who felt a scarcity of opportunity where they were, and where therefore motivated to take risks. Without some kinds of scarcity, or perhaps at least ambition, what drives progress? (Although the Western obsession with progress is an idea worth unpacking on its own).

It’s only the last idea from her list, the endless pursuit of more, that I’m more easily swayed to her position. The endless pursuit of anything makes me think, at first, of mental illness. The endless pursuit of cleanliness. The endless pursuit of stuff hoarded in your apartment. The endless pursuit of pictures of kittens in hats. The endless pursuit of status and conspicuous wealth. The endless pursuit of endless pursuits.

Of course, some pursuits are noble: the endless pursuit of reducing stupidity or the endless pursuit of helping people be better to each other. Yet somehow the world culture I see often rewards certain endless pursuits far more than others. The developing world is chasing the American dream of the 1950s and 60s, without learning from the mistakes (cars, pollution, suburban sprawl) that came with them. Our economies depend on the endless pursuit of growth which depends heavily on the endless pursuit of selling us things we don’t really need.

We are still struggling with the basic notions of maintaining a long-lasting civilization, but have the hubris to spend most of our time and resources in denial of the biggest challenges to our future. Perhaps the idea we need to consider rejecting most strongly is that we’re good at learning from the past or collectively learning anything at all. There is wisdom here on planet earth, it’s just not yet distributed to the places and people who need it most.

What ideas do you think we most need to reject? I’d like to know. Leave a comment.

January 25, 2018

Contest: Take a photo and win free signed books (+$100)

Do you like to take photos? Do you own at least one of my books? Then this contest is for you.

Take a photo that shows the books of mine you own, share it and you get a chance to win a bundle of all 7 of my books personally signed to you and a $100 Amazon Gift Certificate so you can buy even more books (or other nice things).

To enter to win:

Take a fun photo of your Berkun book inventory (you need at least one book :) Selfies are welcome. Or make it an action photo. Be creative. Make me laugh.

Post it to Twitter, FB (public, otherwise I won’t find it) or Instagram – use #berkuncontest. You can also add it as a comment to this post.

Or if you’re afraid of social media and/or think it has destroyed humanity, just send me a link to the photo.

Sharing the photo enters you into the contest and by entering you give me permission to reuse the photo, OK? Winner will be chosen in a semi-random method of my choosing (but photos that are creative or make me laugh will have extra odds of winning).

To give you some ideas, here are some of the fun photos from a previous contest but I think you can do even better.

January 23, 2018

How to master the ways to say NO

On Tuesdays I write about the top voted question on Ask Berkun (see the lovely archive). This week’s question came from Sam K. [via email]:

I lead a team in a very political organization. It’s hard to make things stick. I want to focus my team but I struggle with how to defend priorities as my boss and her peers often change their minds and commit to more things than we can possibly do. Any advice?

If you can’t say no, you can’t truly say yes either. The reason for this is if you’re always saying yes you’re giving away the limited resources you have to tasks that are not the most important things to do. This is like like having a savings account for retirement where you are always making withdrawals to buy what tempting things you happen to see: it’s not really a savings account anymore. And it follows that a project that says yes to fun, but low priority requests, isn’t really a project anymore: it’s just a collection of random bits of work. Without the authority to say no, it’s nearly impossible to do well at any kind of project.

Sadly some people in management positions struggle with this basic notion (and I fear for the state of their retirement accounts). They want to please everyone, and in trying to please everyone they likely end up failing everyone, as the project work that truly needs to be done never gets completed.

Master the many ways to say no

The reason why every project needs clear priorities is it provides a tool for everyone about what to spend resources on. It tells you what kinds of ideas or requests what to say yes and no to. While it can be hard work to get all the leaders to agree to one list of priorities, it’s essential to getting you the leverage needed to say no (and to manage a project well). Once the agreed priorities are in place, that priority list becomes a kind of contract. And you should confirm with the leaders that your job is to defend the priorities, even against requests they might have in the future.

This means when a new idea or request comes in, you simply check the priorities list: if it fits, you can consider it. If it doesn’t you need to say No. There are many different ways to say no and you should master them. You can say it with an explanation, a smile, an argument, a counterproposal, an offering of a glass a wine, or a reminder that you are not just saying no to them, but that you are defending the very priorities that they agree to previously.

To prepare yourself for this, you need to know all of the different flavors that the word no comes in:

No, unless this fits our priorities (which it probably doesn’t). This is the most common flavor of no that wise leaders use. It re-establishes that the priorities drive decisions. Early on in a project this often leads to a rehashing of why the priorities are the priorities, but that’s a healthy discussion. They may suggest a way to refine or clarify how the priorities are written. But the later you are into a healthy project, the firmer you should stand.

No, only if we have time. If you keep your priorities lean, as you should, there will always be many very good ideas that didn’t make the cut. Express this as a relative decision: the idea in question might be good, but not good enough relative to the other work and the project priorities. If the item is on the priority 2 list, convey that it’s possible it will be done if there is extra time, but that no one should assume it will happen.

No, only if you make happen. Sometimes, you can redirect a request back on to the person who made it. If your VP asks you to add support for a new feature, tell him you can do it only if he cuts one of his other current priority 1 requests. This shifts the point of contention away from you, and toward a tangible, though probably unattainable, situation. This can also be done for political or approval issues: “If you can convince Sally that this is a good idea, I’ll consider it.” As you may know that Sally is unlikely to say yes, which sends the requester towards a dead end: but it’s a dead end that leads away from you.

No. Next release. Assuming you are working on a project with more updates (e.g. a website or software project) or sprints, offer to reconsider the request for the next release. This should probably happen anyway for all priority 2 items. This is often called postponement or punting.

No. Never. Ever. Really. Some requests are so fundamentally out of line with the long-term goals that the hammer should come down. Cut the cord now and save yourself the time of answering the same request again later. Sometimes it’s worth the effort to explain why (so that they’ll be more informed next time). Example: “No, Fred. Our mobile app will never support the Esperanto language. Never. Ever. Because no one uses it and never will.”

On the day you are assigned a project, you should clarify with your boss that you need their support in saying no to people. It needs to be established across the organization that in most cases they’ll get the same answer from your boss, as they get from you. You can also familiarize your coworkers with this list of ways you are likely to say no, perhaps even keeping it up on your whiteboard, prepping them for the likely conversations you will have in the future.

This is based on an excerpt from the bestselling project management book, Making Things Happen. Other classic chapters include:

The truth about schedules

How to figure out what to do

What to do when things go wrong

How not to annoy people

Making things happen (the titular chapter)

Power and politics

Buy the bestselling book here

January 9, 2018

Does the attention economy make life harder for creatives?

On Tuesdays I write about the top voted question on Ask Berkun (see the lovely archive). This week’s question came from Daniel H. [23 votes]:

Does the attention economy lead to creative burnout? (And make life harder?)

Trying to make a living doing creative work has always been hard for two reasons:

The work is more emotionally challenging than other kinds of work

There is more competition for income for the kinds of work more people want to do

For these reasons alone it’s no surprise that many writers, designers or even programmers experience burnout in their careers. There’s only so long even the most disciplined and tough personality can persist in making things of their own invention without wearing themselves out. And as is the way with burnout, it’s only once you are past your limits that you discover where you limits are (or how long it will take to recover from crossing them).

It’s true that in today’s short attention span information overloaded age there are new challenges for makers. It’s easy to blame these cultural shifts, and to see how software uses our brains against us, as a problem (and for the future of civilization it’s scary indeed). For creators, the news and information cycle is so fast that to earn attention for your work suggests you have to keep up with it all. But the other side of that technological coin is that it’s easier than ever to make things and distribute them. Most people today have in their pocket everything they need to write a novel, or make a film, and at the click of a button, put it online and make it instantly available to the entire planet. They can even use wonderful tools like Kickstarter, as I have several times, to get their friends, family and fans to help make it happen (something artists have often had to do in the past, from Vincent Van Gogh to Richard Linklater).

Of course the entire planet does not care when yet more media is added to the world (3oo hours of video are posted to youtube every hour, so even if the world cared, they’d still have to prioritize). But even 50 years ago, before the internet, there were more films made each year than anyone could possibly see and more books published annually than anyone could read. For a very long time we’ve been living in a world where there is a surplus of creative works, which therefore means they compete for attention (Herbert Simon wrote about the attention economy as early as 1971). The attention economy has certainly intensified, but it’s part of an old story of how as civilization progresses, the means of creation enter more people’s hands.

One major positive difference that comes along with this change is the number of gatekeepers is lower than ever. Thanks to the web no one can tell me, or you, or anyone, NO, which was true until these last few decades. Before the web there was often no way to get your work distributed unless you had permission. Given the choice of a) depending on the approval of others to finish projects and share them with the world, but having fewer competitors vs. b) being able to put anything into the world, but I have to compete with everyone else for attention, I definitely choose b. At least I have a chance. At least I can compete, and use my skills at creation as an advantage.

Getting back to the attention economy and burnout, the wise answer is that if creativity is a primary resource in your work, you have to manage your emotional health carefully. This means understanding 4 things.

What is a sustainable pace of work for you (that can last for a long career)? This is more about self-awareness than what’s happening on Facebook (or whatever eventually replaces it). How many blog posts or tweets can you write in a week? Or short films? What if you have to average that over a month or a year? Or a lifetime? How much downtime do you need to sustain that level of production? These are questions anyone serious about being a professional maker of things has to consider. You can’t live on all-nighters (and the recovery time from those bold efforts is often longer than people realize).

What is a sustainable amount of income/attention? Much of my income comes from speaking at events. Speaking pays very well and is a short commitment, a combination that gives me the time and funding to support writing projects (including this blog, which is free). Most creative people in history realized they needed multiple paths of income, and attention, to make their life work (or do their life’s work). Only when you sit down and do the math can you understand how best to prioritize your limited time and what kinds of attention to seek (See Should I Quit My Job?).

Attention from fans matters more than the rest of the world. The most famous people in any media get most of the attention. But the fallacy is that you need to be in that top 1% or 5% to make a living. That’s not true. You simply need enough fans and attention to earn you enough money to make a living (an approach services like Patreon have validated). By most measures I am not a famous person, nor a particularly famous author. I’ve made it work over these 15 years because enough people have seen my work and liked it sufficiently to pay for it, recommend it to others and come back for more (and I’m very grateful to them). Maybe you only need attention from a handful of the right people (Patrons of the arts, a specific professional group, venture capitalists, who knows) to earn the balance of the income you need. Michelangelo and Da Vinci were likely unknown names more than a few hundred miles from where they lived. Once you start targeting the attention that helps you most, what the rest of the world is obsessing about doesn’t matter anymore.

A creative life is not the safe and secure path. I wish that it was, but I know it isn’t. The more creative the life you choose, the more risk that will come with it. If you want a secure, predictable career, consider an office job where you work for someone else. You will likely get a salary, health benefits and predictable days of working just from 9am to 5pm, all things I do not get as I am self-employed, just like many writers, bloggers, Youtubers, musicians and filmmakers are. It’s a mistake to enter creative life, including starting your own business, while presuming the outcome is clear. It can be wonderfully rewarding, but as I’ve pointed out in this post, you are choosing to compete to earn a living, and even if you do everything right odds are high you can still fail. I recommend doing it anyway, you will learn more about life and yourself by taking the challenging path, but you should do it with your eyes open.

Did you find this post useful? You can help me write more good works by sharing this post. Thanks.

Related:

Why You Are Not Drowning In Data

Does Information Overload Matter or Get Worse?

How to Surviving Creative Burnout