Scott Berkun's Blog, page 12

March 4, 2016

The Real Reasons Why We Vote The Way We Do

We all tend to think our own political views are sound, but that it’s “the others” that are crazy, dumb or both. To get some perspective this election season, I recently read Political Animals: How Our Stone Age Brain Gets in the Way of Smart Politics, by Rick Shenkman.

We all tend to think our own political views are sound, but that it’s “the others” that are crazy, dumb or both. To get some perspective this election season, I recently read Political Animals: How Our Stone Age Brain Gets in the Way of Smart Politics, by Rick Shenkman.

It’s a good and important book. I’d recommend it for anyone trying to understand what is going on in America and to sharpen their own thinking about who to vote for. Kirkus reviews called it “An amiable tour of the socio-scientific evidence that accounts for our political miscalculations” and that’s a good summary.

The book aims at four observations:

Many of us frequently disengage, becoming apathetic.

We often don’t correctly size up our leaders.

We punish politicians who tell us hard truths.

We often fail to show empathy in circumstances that clearly cry out for it.

And the chapters of the book try to answer four questions:

Why aren’t voters more curious and knowledgeable?

Why do we find reading politicians so difficult?

Why aren’t we more realistic?

Why does our empathy for people in trouble often seem in such short supply?

A central theme of the book is cognitive bias, and how our brains are poorly designed for certain kinds of problem solving (e.g. evaluating candidates). Our brains are designed for life 20,000 years ago, and our natural skills for evaluating leaders don’t work very well at the scale of national governments.

We also have great faith in why we make our own choices, despite the powerful evidence we’re mostly irrational and heavily influenced by superficials. We see this flaw more easily in people who vote differently than we do than in ourselves. Shenkman sites many studies that expose the irrational and biased nature of our psychology as it relates to voting. It’s an eye-opening read in many ways, as it’s shocking to read so many stories from American history of our citizen’s absurd and subconscious motivations.

The weakness of the book is it is mildly repetitive at times. It’s well written and provocative, but some points are made multiple times and a tighter edit would have made it a smoother read. Like many books about culture, his arguments depend heavily on social psychology studies, which are easy to interpret in different ways (to his credit the Notes section is a thorough referencing of every study mentioned). It’d be easy to accuse the book of a liberal bias (Nixon and Reagan are used as negative examples), but that would miss the point. Most of his observations and evidence apply to our species in general, rather than a point of view. Swap out some examples and his points still resonate.

“We possess dozens of instincts— perhaps even thousands depending on your definition— and they involve virtually any human activity you can think of. William James, the father of American psychology, held that instincts guide us from birth. He even included crying and sneezing as instincts. You don’t have to be taught to cry or sneeze, after all.”

“The key to understanding how the modern mind works is to realize that its circuits were not designed to solve the day-to-day problems of a modern American— they were designed to solve the day-to-day problems of our hunter-gatherer ancestors. These stone age priorities produced a brain far better at solving some problems than others.”

“Bartels and Achen found, adverse weather conditions cost the incumbent party 1.5 percentage points. In close elections, that could spell the difference between a win and a loss. (More than half of presidential elections since 1900 have been won by five points or less.)”

“How can we tell when we should follow our instincts and when we should not?”

“Our evolved mechanisms, as Michael Bang Petersen points out, are designed to help us evaluate people in our midst. They are less good at helping us evaluate people at a distance. Our natural gifts of reading people are largely neutralized when we are reading politicians. The circumstances in which we get to know them are so artificial, it’s impossible most of the time to get a whiff of the real person beneath the fictional character created for public consumption. We think we know our politicians well. But we barely know them at all.”

“Like most elections, 1980 was a referendum on the past. People generally don’t vote on the basis of what they expect will happen in the future. The future is abstract. The past, in contrast, is concrete. As emotional human beings we respond most forcefully to the concrete. People didn’t vote for Reagan so much as vote against Carter.”

“As the Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker has observed, we don’t want the truth to prevail, we want our version of the truth to prevail.”

“So who paid the most attention? Who, in other words, formed the main audience for the election? This was perhaps the study’s central finding. It was partisans— the people who had already made up their minds. The key audience wasn’t the people who had an open mind. It was the people who had closed minds. They didn’t follow the news to get educated. They followed the news because they found it interesting. The media had virtually no impact on their views. When they heard what they wanted to hear, they cheered.”

Quotes from Political Animals: How Our Stone Age Brain Gets in the Way of Smart Politics, by Rick Shenkman.

The Real Reasons We Vote The Way We Do

We all tend to think our own political views are sound, but that it’s “the others” that are crazy, dumb or both. To get some perspective this election season, I recently read Political Animals: How Our Stone Age Brain Gets in the Way of Smart Politics, by Rick Shenkman.

We all tend to think our own political views are sound, but that it’s “the others” that are crazy, dumb or both. To get some perspective this election season, I recently read Political Animals: How Our Stone Age Brain Gets in the Way of Smart Politics, by Rick Shenkman.

It’s a good and important book. I’d recommend it for anyone trying to understand what is going on in America and to sharpen their own thinking about who to vote for. Kirkus reviews called it “An amiable tour of the socio-scientific evidence that accounts for our political miscalculations” and that’s a good summary.

The book aims at four observations:

Many of us frequently disengage, becoming apathetic.

We often don’t correctly size up our leaders.

We punish politicians who tell us hard truths.

We often fail to show empathy in circumstances that clearly cry out for it.

And the chapters of the book try to answer four questions:

Why aren’t voters more curious and knowledgeable?

Why do we find reading politicians so difficult?

Why aren’t we more realistic?

Why does our empathy for people in trouble often seem in such short supply?

A central theme of the book is cognitive bias, and how our brains are poorly designed for certain kinds of problem solving (e.g. evaluating candidates). Our brains are designed for life 20,000 years ago, and our natural skills for evaluating leaders don’t work very well at the scale of national governments.

We also have great faith in why we make our own choices, despite the powerful evidence we’re mostly irrational and heavily influenced by superficials. We see this flaw more easily in people who vote differently than we do than in ourselves. Shenkman sites many studies that expose the irrational and biased nature of our psychology as it relates to voting. It’s an eye-opening read in many ways, as it’s shocking to read so many stories from American history of our citizen’s absurd and subconscious motivations.

The weakness of the book is it is mildly repetitive at times. It’s well written and provocative, but some points are made multiple times and a tighter edit would have made it a smoother read. Like many books about culture, his arguments depend heavily on social psychology studies, which are easy to interpret in different ways (to his credit the Notes section is a thorough referencing of every study mentioned). It’d be easy to accuse the book of a liberal bias (Nixon and Reagan are used as negative examples), but that would miss the point. Most of his observations and evidence apply to our species in general, rather than a point of view. Swap out some examples and his points still resonate.

“We possess dozens of instincts— perhaps even thousands depending on your definition— and they involve virtually any human activity you can think of. William James, the father of American psychology, held that instincts guide us from birth. He even included crying and sneezing as instincts. You don’t have to be taught to cry or sneeze, after all.”

“The key to understanding how the modern mind works is to realize that its circuits were not designed to solve the day-to-day problems of a modern American— they were designed to solve the day-to-day problems of our hunter-gatherer ancestors. These stone age priorities produced a brain far better at solving some problems than others.”

“Bartels and Achen found, adverse weather conditions cost the incumbent party 1.5 percentage points. In close elections, that could spell the difference between a win and a loss. (More than half of presidential elections since 1900 have been won by five points or less.)”

“How can we tell when we should follow our instincts and when we should not?”

“Our evolved mechanisms, as Michael Bang Petersen points out, are designed to help us evaluate people in our midst. They are less good at helping us evaluate people at a distance. Our natural gifts of reading people are largely neutralized when we are reading politicians. The circumstances in which we get to know them are so artificial, it’s impossible most of the time to get a whiff of the real person beneath the fictional character created for public consumption. We think we know our politicians well. But we barely know them at all.”

“Like most elections, 1980 was a referendum on the past. People generally don’t vote on the basis of what they expect will happen in the future. The future is abstract. The past, in contrast, is concrete. As emotional human beings we respond most forcefully to the concrete. People didn’t vote for Reagan so much as vote against Carter.”

“As the Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker has observed, we don’t want the truth to prevail, we want our version of the truth to prevail.”

“So who paid the most attention? Who, in other words, formed the main audience for the election? This was perhaps the study’s central finding. It was partisans— the people who had already made up their minds. The key audience wasn’t the people who had an open mind. It was the people who had closed minds. They didn’t follow the news to get educated. They followed the news because they found it interesting. The media had virtually no impact on their views. When they heard what they wanted to hear, they cheered.”

Quotes from Political Animals: How Our Stone Age Brain Gets in the Way of Smart Politics, by Rick Shenkman.

March 1, 2016

Why Do Idiots Get Ahead?

On Tuesday’s I often write about the top voted question on Ask Berkun (see the archive). This week’s question is from Cedric with 101 votes] is Why Do Idiots Get Ahead?

I’m a diligent individual, but find it frustrating to continually clean up after the mess “idiots” create – but yet the “idiots” cannot be stopped. I have clout in my organization, yet individuals below me are supported by peers, while I’m ignored.

Your question is an interesting one, but not just for workplaces. As an experiment, lets turn your question around. Why Do Smart People Get Ahead?

I’m not sure they always do. The greatest single factor for how far ahead we get in life is simple: where and when we are born. If you were born in ancient Rome it was 50/50 you’d live past 10 years old no matter how smart you were. Then again, if your Dad was Louis XIV, King Of France in 1644, and you were the first son, you’d be far ahead before you said a single world. There were thousands of other smarter kids born that same day in France, but none were given the same advantages. Monarchy seems pretty limiting to us now, but even today who our parents were defined hundreds of advantages or disadvantages we didn’t pick, but often take credit for. Of course there are no guarantees: many children of the rich and famous often have a terrible time living up to the burdens of those legacies. But my point is there are many factors that define who succeeds in the universe, some we control but many we don’t. Some seems fair to us and some unfair.

Specific to the question of idiots, smarter people get ahead only when they are able to successfully apply their abilities to the situations and challenges they face. Some challenges in life depend more on social skills, passion, empathy, dedication and ambition than smarts. More so, words like smart, dumb, intelligent and idiot are used very loosely. Howard Gardner defined at least nine types of intelligence, including spatial and inter-personal smarts. Depending on what we’re talking about (life? work? sports?) different kinds of intelligence yield different advantages. Some titans of industry have terrible social lives. Many of our most prolific artists struggle with depression. Life is more complex than the simple scorecard we often use to judge others, and ourselves, with. “Getting ahead” seems a lousy measurement, since it demands the question: ahead of whom?

There are five different ideas hidden inside your question, as it relates to the working world:

Meritocracy depends on who defines merit. An idiot could easily get ahead in an organization that decided idiots are awesome. A crazy (or idiotic) CEO could say “we will give a 20% raise and rank promotion to the dumbest people we have.” With an incentive to be stupid, what would merit mean? We tend to think about meritocracy in simple, selfish terms, but it’s highly subjective and local to your culture. Some cultures value politeness, others directness. Banks reward consistency, but startups reward ambition. you find yourself in a place where your definition of merit, or morality, doesn’t match those around you there are only 4 choices: influence their definition, change yours, accept your fate or move on.

When something goes wrong, look up. If ever you wonder why a team or group is a mess, look directly at their collective boss (or parent). It’s their job to make it not that way. If dysfunction and incompetence are common, blame who is in charge. Do you have a coworker who is truly incompetent? If yes, then ask: who has the power to fire them but hasn’t yet? (And who hired them in the first place?). Your problem might simply be your boss is terrible at her job (or her superiors are terrible, which constrains her abilities). The primary responsibility for a boss is to create a functional workplace where competence is rewarded. If the boss is failing to do that, not much else matters. They will spoil most attempts to right the ship, since they prefer it sinking (Perhaps because they are insecure and need to always feel smart, which is best achieved by having fools around them in an endless series of crises only the boss can resolve).

Intelligence is only one valuable attribute. An ambitious person with less talent can often beat a lazy person with more talent. In workplaces, above a minimum level of intelligence, it’s often skills of listening, communicating, earning trust and being reliable that define a person’s reputation. Some abilities, like creativity, persuasiveness and work ethic, aren’t directly tied to intelligence. Someone of average intelligence but who excels at these other skills, and knows their own limitations, can succeed faster than a smarter person who is very difficult to work with or to trust. We’re also influenced by our biases: we like some people and don’t like others for superficial reasons. It’s hard for that bias not to slip into the decisions we make, or who we are willing to support (or not). And of course: if you’re smart enough to know your coworkers are idiots, but not smart enough to work around them or find a new job, how smart are you?

You might be confusing idiocy with disagreement. It’s possible the idiots see you as an idiot too (judgement reciprocity). We’re wired to divide the world into us vs. them distinctions, which often blinds us to the nuances we need to see to begin to understand a different point of view. To say They Don’t Get It might reflect as much about your own limitations as theirs. How do they see the world? How do they see their role or their contributions? Maybe they’re just as frustrated as you are, and recognizing you share this perspective might lead to other kinds of progress.

People rise to their level of incompetence (The Peter Principle). The reasons people are promoted often have more to do with the work they’ve done than their ability to play the role they’re promoted into. An exceptional soldier might be a terrible manager or leader of other soldiers. It’s a common trap in organizations that the only way to earn more money is to take on a management role. This motivates people who have no real interest in leadership or management to take those positions. Once there, their mediocrity prevents them from further promotion, but their pride prevents them from seeking “demotion” to a role they are better suited for.

February 23, 2016

My Eight Favorite Podcasts

Between daily workouts at the gym and frequent bus rides, I go through hours of podcasts every week. I’ve tried out dozens of different ones, and I’ve arrived at the list that make up most of my listening. I can’t promise this list will be good for you: why you listen and what you enjoy likely won’t match my interests. But these are the podcasts I often recommend.

My Eight Favorite Podcasts

BackStory – three American historians pick an important topic for each episode and go back through U.S. history with the goal of extracting lessons and comparisons with the present. They often pick timely subjects like: domestic terrorism, elections, satire in America, or popular court trials (e.g. Serial/Making of A Murderer). I used to be surprised how each episode made me rethink my opinions, but now I’m less surprised. Fantastic show that challenges your assumptions.

Think – A straightforward interview program. It’s a simple show where authors talk about their new books and ideas. Host Krys Boyd consistently asks good, albeit often safe, questions, has good guests (some I’ve heard of before but many not) and outputs several episodes a week. I find many new books to read from her show. Try Rebuilding Our Roads or The 50th Percentile.

This American Life – The wonderful progenitor of so much modern storytelling (and podcast styles). Depending on the topic for each episode I might skip past, but they’re often so brave in the kinds of stories they’re willing to tell and so exceptional in how they tell them, that I’m a dedicated subscriber anyway. Try The Super, The Giant Pool of Money, or Retraction (on the Mike Daisy truth/storytelling scandal).

Here’s the Thing – I was surprised by how good an interviewer Alec Baldwin, the show’s host, is. Given his fame he gets exception guests and gets them to answer questions, and respond authentically, in ways you’d never hear in a standard interview. Try this excellent episode where he interviews Dustin Hoffman and Edie Falco.

In Our Time – A BBC Radio show exploring classical literature, history, philosophy, or science. Host Melvyn Bragg joins with two or three top class academic experts on the week’s subject, and leads them in a discussion about it. It’s an intensely intellectual show – they don’t play down very much to the audience (Bragg does a solid job of reframing and clarifying on behalf of the audience when needed, but sometimes it’s over my head). Start with Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, Salem Witch Trials, or Marie Curie.

The Gist – This news show centers on the talents of Mike Pesca. I love his blend of playful sarcasm with serious questions and commentary about what’s going on in the world. Currently one of my favorite shows. I don’t like all his jokes, but there is a cleverness running through everything on the show that pays off far more often than it doesn’t and I appreciate the effort even when it doesn’t work. Try He Watched Every Superbowl or Exercise Fad B.S. He often closes the show with exceptional insights like this one.

The Weeds – A political policy show by Vox.com. The podcast’s name refers to their goal of staying out of the weeds of sensationalized, shallow, political reporting. Instead they focus on policy, and the history of policy creation. I don’t remember how I found it, but I’ve been really happy with the depth of show, and how good a job they do making the creation of public policy interesting. Try Will Taxing The Rich Hurt Growth?, Immigration and the Minimum Wage and How Politics Is Making Us Stupid.

The Moth – this podcast is based on the live show of true stories told live, without notes. The podcast takes some of the best stories and compiles them in each episode. It’s wonderfully simple, diverse and thought provoking. Highly recommended, especially if you have an interest in storytelling of any kind. Try this exceptional story by Colin Quinn, about Robert DeNero’s birthday party.

Notable Podcasts

I don’t listen to these as regularly, but when I see a topic I’m interested in, or run out of other podcasts, I jump into these.

WTF – Comedian Marc Maron’s long running show is centered on him interviewing one or two guests per episode. He is a often a good interviewer, but I find the pleasure I derive from him and the show inconsistent. I’ll listen if I know of the guest or their work. He often has an opening monologue, which some people love, but I nearly always skip (in part because it ends with his sponsor advertisements). Try this episode where he interviews NPR’s Terry Gross or Obama.

Radiolab – a brilliant re-interpretation of This American Life, and various other ideas. The show centers on the conversations between its two hosts (but spirals outwards for much of the show), and has a style that is more energetic and unpredictable than most shows of its kind.

Song Exploder – They interview a musician about how a song was written, and then play the song. It’s simple and fantastic. I listen to all their episodes where I know the artist or the song. Try this episode with Bjork (she is wonderfully eloquent here and I recommend it whether you like her music or not).

99% invisible – This is the show I recommend most to engineers, designers and people interested in how the world is made. But for reasons I don’t fully understand, I don’t listen to the show (part of it is I find Roman Mars’ voice distracting – sorry Roman!).

Based on my list, is there a podcast you think I should try? Leave a comment.

January 28, 2016

8 Reasons To Take My Public Speaking Workshop (April in Seattle)

I recently announced a new workshop on public speaking, taught here in Seattle. Here’s why you should sign up:

You will have fun. Yes, it’s true. Public Speaking can be fun. The exercises and games we play are designed to make you feel safe, comfortable and have fun while you learn.

Leave with confidence. Since you’ll spend much of the day speaking, or critiquing other speakers, when it’s over you’ll be a much better speaker than ever before. You will learn techniques to manage your fears, and how to prepare to give any presentation with confidence.

It has amazing reviews. Here are results from the last offering:

You will become a better storyteller. You’ll understand the common mistakes speakers make, how to avoid them, and how to use these skills to help you in your career.

The day is centered on YOU. This is a WORKshop. You will spend as much time as logistically possible practicing and getting constructive critique (there are other students of course, but you’ll be working at times in small groups, practicing and getting feedback).

Leave with helpful resources. You’ll get a signed copy of the bestseller, Confessions of A Public Speaker, the book that’s helped thousands of people become better speakers. Plus you’ll get a feedback and critique guide, useful for practice on your own.

Learn from true expertise. I make much of my living as a professional speaker, and have given hundreds of lectures around the world. I’ve appeared on NPR, CNN, MSNBC and CNBC as an expert on various subjects, including public speaking. Over the last 20 years I’ve made every mistake imaginable, and teach from a place of invitation: I want you to improve and learn from my mistakes.

It’s Inexpensive. This is the final discount/beta offering of the course, at a very thrifty $350 (Early Bird) for a full day of first rate training.

Note: this is an intro to intermediate level workshop.

Next offering: In Seattle – Friday April 22nd, 9am – REGISTER HERE.

7 Reasons To Take My Public Speaking Workshop (Feb in Seattle)

I recently announced a new workshop on public speaking, taught here in Seattle. Here’s why you should sign up:

You will have fun. Yes, it’s true. Public Speaking can be fun. The exercises and games we play are designed to make you feel safe, comfortable and have fun while you learn.

Leave with confidence. Since you’ll spend much of the day speaking, or critiquing other speakers, when it’s over you’ll be a much better speaker than ever before. You will learn techniques to manage your fears, and how to prepare to give any presentation with confidence.

You will become a better storyteller. You’ll understand the common mistakes speakers make, how to avoid them, and how to use these skills to help you in your career.

The day is centered on YOU. This is a WORKshop. You will spend as much time as logistically possible practicing and and getting useful feedback (there are other students of course, but you’ll be working at times in small groups, practicing and getting feedback).

Leave with helpful resources. You’ll get a signed copy of the bestseller, Confessions of A Public Speaker, the book that’s helped thousands of people become better speakers. Plus you’ll get a feedback and critique guide, useful for practice on your own.

Learn from true expertise. I make much of my living as a professional speaker, and have given hundreds of lectures around the world. I’ve appeared on NPR, CNN, MSNBC and CNBC as an expert on various subjects, including public speaking. Over the last 20 years I’ve made every mistake imaginable, and teach from a place of invitation. I want you to improve and learn from my mistakes.

It’s Inexpensive. This is the final discount/beta offering of the course, at a very thrifty $299 for a full day of first rate training.

Note: this is an intro to intermediate level workshop.

Next offering: In Seattle – Friday February 12th, 9am – REGISTER HERE.

January 20, 2016

iPhone vs. Light Switch: which invention is more impressive?

If you could only pick one, would you rather have power in your home or a working iPhone?

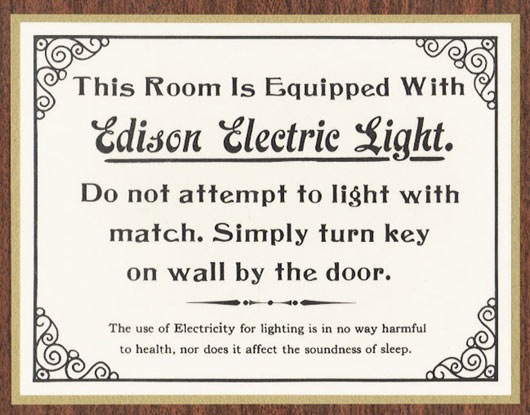

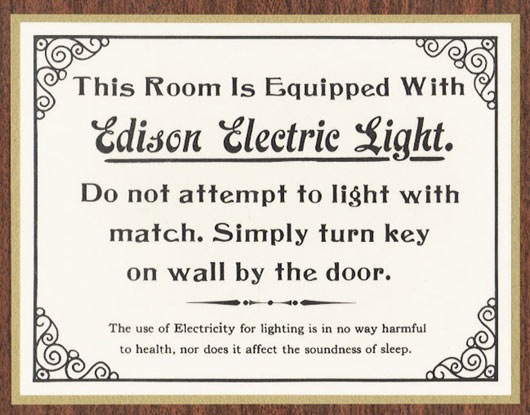

We tend to believe that the latest inventions are the most significant, but often the opposite is true. Running water, electricity, shelter, heat, safe sources of food, and good medical care are far more important for quality of life than nearly anything else. And as far as convenience, a reliable power source in our homes that we can activate with the flick of a switch (something 25% of the planet’s population still does not have) is more impressive than an invention than merely uses that power.

I admit comparing technologies across time is unfair in some ways, as domestic electricity was invented first. But in terms of how much we depend on particular inventions to live, comparisons are useful. The exercise exposes how much we take for granted. Or perhaps more importantly, improves our aim for new inventions that do more than attempt to add convenience, but that truly improve our lives.

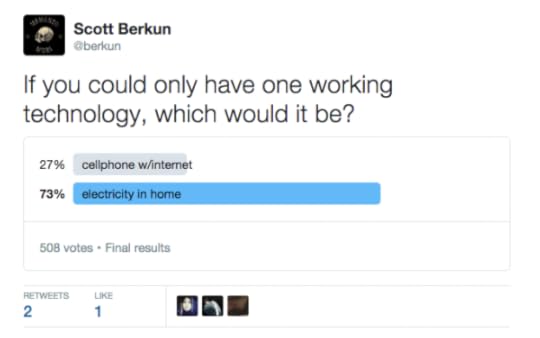

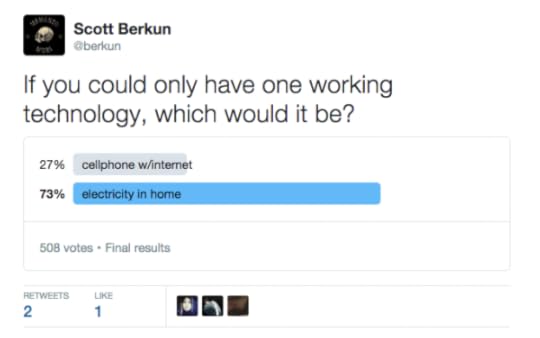

I recently conducted a simple poll on twitter, asking the question:

Of 508 votes, 73% voted for electricity, and 27% for the cellphone (The poll didn’t let me explain, but my intention was the the cellphone could have unlimited power of its own and the internet worked fine on it. But if you chose electricity, you could not have a cellphone).

My belief is that for many among the 27%, if they actually experienced this choice for more than 24 hours, their answer would change. They underestimate how much they depend on electricity to do for them, from keeping their food cold, to heating their apartment, to washing their clothes and keeping the lights on (better go buy some Apple candles).

In a recent post comparing Tesla to Steve Jobs, writer Rajan suggests the light switch is at least as impressive an invention as the iPhone. And I agree. If for no other reason, the invention of domestic electricity had to be done without the benefit of electricity itself. In the 1880s, in the age of horse drawn buggies and hand (or steam) powered tools, they had to not only invent electric power generators, and neighborhood transformers, but also provide the installation of physical power lines across cities, streets and sidewalks. To upgrade a phone is easy, but how would you upgrade the entire power grid of a city? Far more challenging. The rate of technology change is faster today, but mostly with technologies that are far easier to upgrade.

The iPhone and the light switch are both tips of the innovation iceberg. They depend on a massive network of other technologies and inventions to function. With no internet or cell service, a cellphone has limited use, just as a light switch in a house that hasn’t paid its power bills, doesn’t do much at all. As consumers we only see the final interface, the last layer, but what makes an invention impressive or not might be best understood by studying the amazing things required to make that interface work, that in daily use we’d never even notice.

Electricity demanded the introduction of entirely new concepts to ordinary citizens. A transformation the iPhone did not have to force, as its very name reuses concepts well known by the average citizen when it was released in 2007 (its arguably an amazingly powerful wireless telephone). The technological and conceptual leap of in home electricity likely surpasses, in impact on daily (and night) life anything we’ve invented in the last two decades (facts supported by the excellent book, Empires of Light: Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse, and the Race to Electrify the World).

If you disagree, do this simple exercise: go for 48 hours without using electricity in your home (except the power required for your cellphone and internet access). Then report back and leave a comment.

iPhone vs. Light switch: which invention is more impressive?

If you could only pick one, would you rather have power in your home or a working iPhone?

We tend to believe that the latest inventions are the most significant, but often the opposite is true. Running water, electricity, shelter, heat. safe sources of food, and good medical care are far more important for quality of life than nearly anything else. And as far as convenience, a reliable power source in our homes that we can activate with the flick of a switch (something 25% of the planet’s population still does not have) is far more impressive than an invention than merely uses that power.

I admit comparing technologies across time is unfair in some ways, as domestic electricity was invented first. But in terms of how much we depend on particular inventions to live, comparisons are useful. The exercise exposes how much we take for granted. Or perhaps more importantly, improves our aim for new inventions that do more than attempt to add convenience, but that truly improve our lives.

I recently conducted a simple poll on twitter, asking the question:

Of 508 votes, 73% voted for electricity, and 27% for the cellphone (The poll didn’t let me explain, but my intention was the the cellphone could have unlimited power of its own, and the internet worked fine. But if you chose electricity, you could not have a cellphone).

My belief is that for many among the 27%, if they actually experienced this choice for more than 24 hours, their answer would change. They underestimate how much they depend on electricity to do for them, from keeping their food cold, to heating their apartment, to washing their clothes and keeping the lights on (better go buy some Apple candles).

In a recent post comparing Tesla to Steve Jobs, writer Rajan suggests the light switch is at least as impressive an invention as the iPhone. And I agree. If for no other reason, the invention of domestic electricity had to be done without the benefit of electricity itself. In the 1880s, in the age of horse drawn buggies and hand powered tools, they had to not only invent electric power generators, and neighborhood transformers, but also provide the installation of physical power lines across cities, streets and sidewalks. To upgrade a phone is easy, but how would you upgrade the entire power grid of a city? Far more challenging.

The iPhone and the light switch are both tips of the innovation iceberg. They depend on a massive network of other technologies and inventions to function. With no internet or cell service, a cellphone has limited use, just as a light switch in a house that hasn’t paid its power bills, doesn’t do much at all. As consumers we only see the final interface, the last layer, but what makes an invention impressive or not might be best understood by studying the amazing things required to make that interface work that in daily use we’d never even notice.

Electricity demanded the introduction of entirely new concepts to ordinary citizens. A transformation something like the iPhone did not have to make, as its very name reuses concepts well known by the average citizen when it was released in 2007. The technological and conceptual leap of in home electricity likely surpasses, in impact on daily (and night) life anything we’ve invented in the last two decades (facts supported by the excellent book, Empires of Light: Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse, and the Race to Electrify the World).

If you disagree, do this simple exercise: go for 48 hours without using electricity in your home (except the power required for your cellphone and internet access). Then report back and leave a comment.

January 5, 2016

Creativity Is Not An Accident

Many of our popular stories of discovery are portrayed as accidents or matters of luck. We love these stories as they make creativity seem easy and fun, regardless of how misleading they are.

A recent NYTimes opinion titled Cultivating The Art of Serendipity, by Pagan Kennedy, offered:

“A surprising number of the conveniences of modern life were invented when someone stumbled upon a discovery or capitalized on an accident: the microwave oven, safety glass, smoke detectors, artificial sweeteners, X-ray imaging. “

What’s overlooked is that these accidents were earned. Each of these professionals committed themselves to years of work chasing hard problems, and then, when an accident happened, they chose not to ignore it, as most of us would. They chose to study the accident. Who among us studies our accidents? We mostly run and hide from them. Being curious about our own mistakes is a far more interesting attitude for life than someone who merely chases serendipity. Capitalizing on ‘accidents’ is an excellent notion that Kennedy mentions, however briefly, and I wish it were the focus of the article.

A common pattern of the Myth of Epiphany is creativity by accident. The very idea of the Muse, forces that choose to grant ideas to us from above, externalizes creativity, and accidents have similar appeal. Since we’re all often victims of accidents, we’re compelled by stories that redeem accidents into breakthroughs. Newton watching an apple fall, an ordinary event anyone could observe, is perhaps the greatest example of this kind of misleading storytelling (it took him years of work to describe the mathematics of gravity regardless of the apple’s disputed epiphanistic potency).

Kennedy’s opening example continues the myth’s stereotype:

In 2008, an inventor named Steve Hollinger lobbed a digital camera across his studio toward a pile of pillows. “I wasn’t trying to make an invention,” he said. “I was just playing.” As his camera flew, it recorded what most of us would call a bad photo. But when Mr. Hollinger peered at that blurry image, he saw new possibilities. Soon, he was building a throwable videocamera in the shape of a baseball, equipped with gyroscopes and sensors.”

A quick read of Hollinger’s own page about the invention (called a Serveball) reveals important facts that distinguish him from most of us readers. The list includes:

He was a professional inventor and artist (successful enough to be profiled in The New Yorker in 2008)

He had a workshop for inventing things

He worked over the course of a year on this project (which Kennedy refers to as ‘soon’)

He built elaborate rigs capable of hosting multiple cameras

Hollinger stated “I was just playing” and I agree that play is a fantastic use of time and helpful towards developing skills for invention and creation for everyone. But it’s important to note that Hollinger’s idea of play is likely different from ours. It’s serious play. As the New Yorker described in 2008, this is no ordinary person:

He had spent the previous month mostly locked in his apartment, furiously teaching himself the principles of aerodynamics, the physics of hydrology, and the basics of how to operate a Singer sewing machine, and he was at last testing what he had been working on—a reimagined, reinvented umbrella, with gutters and airfoils and the elegant drift of a bird’s wing.

But Kennedy continues to emphasize accidents and randomness:

A surprising number of the conveniences of modern life were invented when someone stumbled upon a discovery or capitalized on an accident: the microwave oven, safety glass, smoke detectors, artificial sweeteners, X-ray imaging. Many blockbuster drugs of the 20th century emerged because a lab worker picked up on the “wrong” information.

Care to guess about the context these stumbles and accidents arrived in?

Microwave oven: In 1945 Percy Spencer, an engineer at Raytheon, discovered a candy bar that melted in his pocket near radar equipment. He chose to do a series of experiments to isolate why this happened and discovered microwaves. It would take ~20 years before the technology developed sufficiently to reach consumers.

Safety Glass: In 1903 scientist Edouard Benedictus, while in his lab, did drop a flask by accident, and to his surprise it did not break. He discovered the flask held residual cellulose nitrate, creating a protective coating. It would be more than a decade before it was used commercially in gas masks.

Artificical Sweeteners: Constantine Fahlberg, a German scientist, discovered Saccharin, the first artificial sweetener, in 1879. After working in his lab he didn’t wash his hands, and at dinner discovered an exceptionally sweet taste. He returned to his lab, tasting his various experiments, until rediscovering the right one (literally risking his life in an attempt to understand his accident).

Smoke Detector: Walter Jaeger was trying to build a sensor to detect poison gas. It didn’t work, and as the story goes, he lit a cigarette and the sensor went off. It could detect smoke particles, but not gas. It took the work of other inventors to build on his discovery to make commercial smoke detectors.

X-Rays: Wilhelm Roentgen was already working on the effects of cathode rays during 1895, before he actually discovered X-rays. was a scientist working on cathode rays. On November 8, 1895, during an experiment, he noticed crystals glowing unexpectedly. On investigation he isolated a new type of light ray.

And how many accidents among similarly talented and motivated people were dead ends? We are victims of survivorship bias in our popularizing of breakthrough stories, giving attention only to successful outcomes from accidents, while ignoring the vast majority of accidents and mistakes that led absolutely nowhere.

To be more helpful, work is the essential element in all finished creative projects and inventions. No matter how brilliant the idea, or miraculous its discovery, work will be required to develop it to the point of consumption by the rest of the world. And it’s effort, even if in pursuit of pleasure, that provides the opportunity for serendipity to happen. Every writer, artist and inventor is chasing something, even if it turns out to be the wrong thing, on their way to their moments of insight. There is no way to pursue only the insights themselves, anymore than you could harvest a garden without planting seeds. The unknown can not be predictable, and if creativity is an act of discovery then uncertainty must be par for the course.

Curiosity is a far simpler concept than serendipity and far more useful. People who are curious are more likely to expend effort to answer a question on their mind. To be successful in creative pursuits requires an active curiosity and a desire to do experiments and make mistakes, having the sensibility that a mistake is a kind of insight, however small, waiting to be revealed.

The Myths of Innovation will never go away, which means for any inspiring story of a breakthrough, we must ask:

How much work did the creator do before the accident/breakthrough happened?

How much work did they do after it the accident/breakthrough to understand it?

What did they sacrifice (time/money/reputation) to convince others of the value of the discovery?

It’s answering these 3 questions about any creativity story in the news, however accidental or deliberate, that lets us examine habits to to emulate if we want to follow in their footsteps.

December 30, 2015

My Best Posts of 2015

Best of lists are fascinating things. They have their problems, but they’re a fun way to summarize, review and organize simultaneously. My method was simple: I reviewed all of my posts of 2015, sorted them by popularity and comments (I read every one and reply to most), and then edited based on my own subjective sense of which ones will best stand the test of time.

Note: this was a very strange year for me professionally, the least productive I’ve had (See My Creative Burnout). I published far less (42 posts, well below my 120+ average) than any year since this blog began in 2003.

If you’ve been reading my work for awhile thanks for sticking around, and if you’re not already on it, join my mailing list – I think of you often and want to reward your loyalty, and that’s the first place I hope to do it in 2016. And if you’ve never heard of me before arriving at this post, I hope these missives below are worthy of you coming back.

Happy new year to you and I wish you the best on making it a great year.

Why Small Ideas Can Matter More Than Big Ideas

The Myth of Epiphany and Eureka Moments

I’m Overwhelmed By Fear, How Do I Gain Confidence?

Why Has Innovation Slowed Down (Or Has It)?

My Creative Burnout (part two)

How Do You Make People Think?

28 Things No One Tells You About Writing & Publishing

The Advice Paradox

Designers, Morality and the AK-47

The Four Lies of Storytelling

How Do You Know When You’re Done Creating Something?

How To Write (A Memoir) – Lessons from writing The Ghost of My Father

What Questions Never Leave You?

Also see: My best posts of all time (2003 – 2013)