Catherine Sevenau's Blog: Writings~Rambles~Rhymes, page 67

October 31, 2014

Sin and Prayer

My parents were like black and white, oil and water, sin and prayer. My father, not one to boil over, married a kettle of emotions. If he could’ve loosened his grip and if my mother hadn’t completely unraveled, perhaps my childhood would’ve have been different. But it was what it was. We all have moments of grace and we all have things happen, I just happened to be inoculated early.

I got the best of Carl and the worst of Babe: I inherited his frame and posture, her moles and droopy eyelids. I possess his sense of rightness, fairness, and goodness, which get me through, her vanity, stinginess, and mouthiness, which get me in trouble. I have his common sense, his work ethic, and reliability—her foolishness, her self-absorption, her pride. I have his manners, conduct, and character—her resentment, entitlement, and disdain. I inherited Daddy’s sociability, Mom’s sarcasm, his loyalty, her indifference, his modesty, her arrogance. I carry his confidence and am weighed down with her self-doubt. I am also his good intentions and her unattended sorrows.

Until I’d met some Chatfield cousins at a reunion, I’d never come across anybody that cared for my mother (well, except my brother, but he couldn’t stand her cigarette smoking). My cousins remembered Mom from when she was young, and thoroughly liked her. They thought she was honest, humorous, and hip. They told me she held her own on just about any subject, was well-read in history and well-versed in sports, and could rattle off team stats with the best of them. Now that I write this, I think it’s not true. I only know four people that disliked Mom: my father and three sisters. They were the ones who had issues with her, though I think Claudia went along just for the ride. Even my brothers-in-law liked my mother. I was glad to find that Babe had people in her court. Maybe she wasn’t as “out there” as I thought. She was just like the rest of her family—who, compared to my father’s family—were all a little out there. It’s all relative.

My sisters and I are much like mom, in that whatever flies into our minds is likely to fall out of our mouths. I’m also hardheaded like my grandmothers, Barbara Clemens and Nellie Chatfield, who were two peas of the same pod. I live in that pod too, that place of rules and righteousness, of stubbornness and inflexibility. I also appreciate that I possess our flip side: our willingness and determination, our trust and persistence.

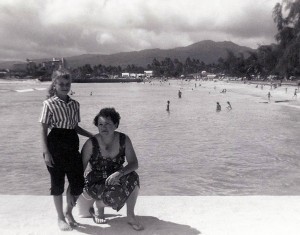

Cathy and Mom, Hawaii, June 1958. This is the only picture I have of the two of us. I left shortly after to live with my sister.

Babe was not the mother I wanted, but she was the one I got. Was she a good mother? No. Did I love her? No, I can’t say I did; I’m not that big. But as life would have it, having her as a mother ended up to be in my best interest. Although she may not have been “good enough” I turned out as well as I have because stand-ins appeared throughout my life: sisters and friends and lovers who filled that mothering gap for me. It pays to be adoptable.

I survived my childhood. I raised two sons as a single mom (I got by with a little help from my friends). I’ve gone from welfare to two successful businesses and a longtime career in real estate. I learned to dance, no small feat for someone with two left ones, and I wrote this book. I thank God I’m a hardheaded woman. I’m not so sure my sons agree, but they’re entitled to my opinion, too.

I imagine my Mother only wanted the same things that I want: to be seen and to be heard. Writing this book did that, for both of us.

Catherine Sevenau

(original version from BEHIND THESE DOOR: A FAMILY MEMOIR)

October 17, 2014

My Friend, Kim Heddy

Kim joined our office as an agent in 1994. As it turned out we had a lot in common: we both loved real estate, ice cream, and dark chocolate. In 2002 she became a partner in my real estate practice: she took over showing property to my clients, which meant I no longer got lost wandering around town looking for streets that were never where I remembered them, organized much of the paperwork, and dealt with the details of short sales when they became the bane of our existence.

Kimmy was diplomatic, charming, and easygoing. The one thing in her way was her indecisiveness, but she made up for it with her determination and spunk. It just wasn’t Kim’s nature to be decisive. “I can’t help it that I’m wishy-washy,” she told me, “I’m a Libra.” As our offices adjoined, I could hear her talking to clients. I’d roll my eyes and wonder how she ever nudged anyone to make a decision. The difficulty in making up her mind could take hold of her, even in mundane choices. Shopping was fraught with internal conflict, so she returned much of what she bought. She admitted once that what she liked most about shopping was returning everything. During the holidays a couple of seasons ago, the back of her SUV was crammed with boxes.

“What is all this stuff?” I asked her.

“I’m taking it all back to the store.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know, I couldn’t decide if any of it was really what I wanted.”

It worked out perfectly for me. I did my Christmas shopping right there in our parking lot.

For ten years Kim and I were joined at the hip. We made a great team, filling in one another’s gaps; I kept her on course and she kept me on track. Many mornings she’d call from the office and always ask the same thing, “What are you doing?” In the middle of family research on Ancestry or Find A Grave, I’d answer, “I’m working on dead people,” and she’d bark back, “Get down here. They’re dead. They’ll wait.”

Then life took a sharp turn. In June of 2011, Kim was diagnosed with Stage IV lung cancer. Her first doctor sent her home with no hope and very little time. A second doctor said, “Wait a minute. You’re young, healthy, and in great shape—you fight this!” She followed that advice, dumping her first doctor. A combination of chemo, daily injections, rounds of doctors, batteries of tests, bottles of pills, tanks of oxygen, prayers, holy water, bodywork, herbal remedies, food from friends, buckets of love, and a fair amount of laughter—along with her great spunk, mettle, and optimism—had Kim outlive the first doctor’s projections by more than a year.

cancer. Her first doctor sent her home with no hope and very little time. A second doctor said, “Wait a minute. You’re young, healthy, and in great shape—you fight this!” She followed that advice, dumping her first doctor. A combination of chemo, daily injections, rounds of doctors, batteries of tests, bottles of pills, tanks of oxygen, prayers, holy water, bodywork, herbal remedies, food from friends, buckets of love, and a fair amount of laughter—along with her great spunk, mettle, and optimism—had Kim outlive the first doctor’s projections by more than a year.

Kim & Catherine, 2012

C21 Convention New Orleans

In those months she recovered enough to return to work. She wasn’t kickboxing, but her breathing was better and her color and smile had returned. She ventured to the Century 21 Annual Convention in New Orleans, enjoyed her sixty-fifth and sixty-sixth birthdays, and with her husband Dan took an Alaskan cruise and celebrated their nineteenth wedding anniversary. She was able to be with her children and grandchildren to celebrate birthdays and holidays. And every afternoon she slowly swam with Dan in the warm water of their lap pool, enjoying the hummingbirds hovering in the yard and watching the same two crows holding court on the branch of their flowering cherry.

Then the cancer spread. The pain in her bones and the inability to breathe sent her back to the hospital where for three weeks her family stayed with her around the clock. I saw Kim twice in her last week. On my first visit we had time alone while the family conferred with doctors. I sat as close as I could without disturbing anything as she was hooked up to monitors, an IV, and had two oxygen contraptions on her face.

“Tell me what’s going on at the office,” she said. I leaned in closer to hear her. “What happened at the meeting today? Did you get the names of the mentor families for the Thanksgiving dinners? And after a long pause, “and my view clients, did you reach them?” Kim’s labored breathing, the oxygen mask, and her small continuous cough made it hard to understand her, and her talking made her cough worse. I told her everything and everyone was taken care of, not to fret.

She faded in and out over the next hour. Then came a moment when she looked straight at me. In a small, clear voice she said, “There’s dark chocolate here in the room. Want some?”

“Yeah,” I said. “How about you, you want some?”

“Yeah,” she whispered back.

I broke off a small piece. Kim struggled to get the chocolate past her mask, and I gently wiped off the leftover smudges on her fingers. We closed our eyes and as heaven melted in our mouths I thought: when I’m dying, I hope that the last thing that passes my lips will be a piece of good dark chocolate.

The final time I saw my friend I knew it would be the last, but neither of us could say goodbye. She didn’t want to leave and I didn’t want her to go, so we left it at that. Two days later, on the eighth of November, 2012, Kim took a final breath, quietly slipping out of this life.

Kim Heddy: Find A Grave Memorial

October 14, 2014

Behind These Doors: Prologue

Clemens siblings, Sonora, California, 1950

L-R: Carleen, Claudia, Cathy (Catherine) in middle, Betty (Liz), Larry (Gordon)

Prologue

Audio (click arrow to play):

http://sevenau.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/1-Prologue.mp3

My brother Larry was under the illusion that our mother was a good mother, but he had a different childhood than the rest of us. My sisters were convinced otherwise: Carleen complained Mom was thoughtless and self-centered, Betty resented her for abandoning us, and Claudia simply thought she was weak—all of which was true by the way. I was never under the illusion I had a bad mother, I was under the illusion I had the wrong mother, and although I was not under the illusion she loved me, I hoped she might someday. I was raised by omission, but neglect doesn’t leave a scar, it leaves a hole. Some say holes are harder to heal. Fortunately, I only lived with her from the time I was five until the age of nine. I figure that’s why I’m not completely neurotic. Or dead.

I wrote our story, which evolved into a five-year journey. A magnitude of personal growth work put it into perspective; a writing class helped me get it down on paper. It’s about doors opened, closed, and locked, and about a family so complicated you’ll need a scorecard. As my friend Billy says, “There are really only five-hundred people on the planet, the rest are just crowd scenes done with mirrors.” It seems I’m friends with, or related to, most of these people. The rest I’ve dated.

My siblings loved my writing. Then a change of heart on my sister’s part regarding something she said I could use caused a major rift, so as not to be cast out, and to honor her wishes, I put the book away. For the next five years I worked on our genealogy. It was safer; they were all dead. My sister has since passed, along with enough time, so I returned to finishing “the book.”

What follows is what I’ve been told, what I recall, and what my family claims I’ve made up. Some stories I’ve never disclosed; some I’ve recounted so many times I can’t remember if they’re even true anymore. But do we ever recollect what actually happened? Certainly we remember our version—and what we believe is true for us, so we better be careful what we believe. And does any of it matter? Only when we make it mean something.

October 8, 2014

Reincarnation

Dec 3, 1939 – Oct 8, 2004

Sixty-four years ago my middle sister was born: Elizabeth Ann “Betty” Clemens.

She was married forty-six years, had four children, and was the funniest person I knew.

A year ago she developed a wracking cough.

Eight months ago she was diagnosed with stage four Adeno Sarcoma, a lung cancer.

Two months ago she was accepted in an experimental cancer treatment, her only possible hope.

Three weeks ago she had lung surgery for the making of a vaccine from her own cells.

Two weeks ago she came to stay with me.

We talked, laughed, told stories, and had a few visitors.

We were anxious and we were scared.

We slept a little, ate a little, cried a little.

I bathed her body, changed her clothes, combed her hair, rubbed her swollen ankles.

I brought her food and water and pills and tissues and oxygen tanks and blankets and love.

I was washing her feet.

She said I would not come back as a cockroach.

I said I didn’t think you believed in reincarnation.

She said she must be getting religion.

A week ago Liz took a turn for the worse.

Four days ago I drove her back to the hospital in Sacramento. She had pneumonia.

Each day her daughter Julie phoned me and said Liz was getting weaker.

This morning my sister died.

She simply had no breath left in her. I think she was too tired to be scared—and I know she was too frail to go on.

Tomorrow my son and I will meet my brother and his wife in Carmel and drive to Liz’s home in Fallbrook.

The next day there will be a small family gathering.

The day after that,

and the day after that,

and the day after that,

we will celebrate her life.

One day at a time.

Catherine Sevenau

October 2004

Ten Years Have Slipped By

Yesterday I found out my sister is dying. I know, thousands of people die every day—but they’re not my sister. She’s had this constant wracking cough for three months and we finally got her to go to a doctor. The first one said it was allergies and sent her home with nasal spray. When the cough persisted, she got a second opinion: pneumonia and antibiotics, then a third diagnosis: tuberculosis, then a fourth: Valley Fever. Finally she saw her husband’s cancer specialist. The tests came in yesterday.

The picture of her right lung shows it filled with snowballs of thousands of tiny white threads, the biopsy confirming Adeno Sarcoma, cancer of the soft tissue. Last week our hope was that it hadn’t spread beyond her one lung. But it has: it’s in the lung’s outer lining and in the back of her ribs; it may be in her brain, the part of her body she most values. How ironic. My sister is smarter than anybody I know except maybe her husband. She and Tony argue and compete for who knows more—which date, who’s right, what’s fact—and there isn’t anything they don’t know something about. They collect trivia and knowledge like others collect tea sets and clocks. I told her no need to worry, even if half her brain cells disappeared, she’d still be smarter than the rest of us.

How does my sister feel about dying? During the day she’s matter-of-fact about it. As she walked up her long wide driveway lined with lemon trees and date palms to get her newspaper this morning, she passed her neighbor.

“How’s it going?”

“Aingh,” she replied, then added in afterthought, “I have lung cancer.”

“They have cures for that today,” he said.

“Not for what I have,” she tossed over her shoulder, scooping up her paper and turning back down her shaded path.

How do I feel about her dying? Sometimes, I too am matter-of-fact. I believe when we die, when we leave our body, our soul survives. I don’t know where it goes or what happens; maybe we come back and get to do this all over again. Other times, when I’m not so matter-of-fact, when I think about her death and try to imagine her not here, my heart rends. Liz doesn’t cry, so I cry for us both.

My sister believes that when we die, that’s it. She wants this huge headstone with two carved angels and three pictures of herself at different ages on it so people won’t forget her. I told her I didn’t think all that many will be lined up to visit it, especially if she didn’t start being a little nicer. My sister has a bite, which is partly what I love about her. She’s the only person I know who tells the truth about everything, to everyone, at anytime. Well, she thinks it’s the truth anyway and usually she’s right, but it does get some riled.

Julie, Catherine, Liz

1988, Sonoma

I’m one of the few who escapes Liz’s tongue, partly because I fold so easily around her. She loves me, so she’s tender with my feelings. It’s impossible not to love someone who loves you that much. I can’t imagine what it will be like without her. Who will call me every week just to talk? Who will I phone three times a day to help me with my family memoir writings, to tell me I made this part up, that I better not put that part in because it will hurt our brother’s feelings, then give me a lesson on homesteading or weirs or the Civil War? Who will I dial when I just want someone to agree with me, or I want to be heard, or I want someone to tell me the truth? Oh it’s not like I don’t have others like her in my life—but they’re not her. I’ll miss her wicked laugh, scathing wit, and opinionated righteous stubbornness. And I’ll miss her love for me. I’m trying not to make her dying about me, about what I won’t have, about my loss. I’m doing my best to stay out of that space; I know it doesn’t help her.

We don’t know how long she has—perhaps just months. But sometimes miracles happen, so I told her not to start giving her stuff away just yet. She’s planning a big going away celebration; she wants to be there when everyone comes to pay their last respects. Some won’t be invited: she hasn’t spoken to her oldest daughter in five years, can’t abide her brother-in-law, and isn’t talking to our sister Claudia. They’ve all crossed her line and she refuses to forgive them. She demands that none of us tell them she’s dying. “I don’t want them applauding my demise, singing and cheering and dancing a jig on my grave.” (I keep my mouth shut about how she danced on Mom’s.) She doesn’t give a whit if things don’t get worked out with them before she goes. I’m trying to mind my own business about that one too.

Elizabeth Ann (Clemens) Duchi

1939 – 2004

I told her I’d help pick out her headstone; I don’t trust her not to get something too gaudy. But it’s her funeral—so if she wants to pick out the biggest, most elaborate marble headstone we can find—she can. Maybe we’ll get three angels and have the whole thing special ordered from Italy, like the stunning tile in her new kitchen. She’d like that. I’ll phone her about it tomorrow.

Catherine Sevenau, 2004

Note: the angels and more pictures are on the reverse of her stone

Writings~Rambles~Rhymes

- Catherine Sevenau's profile

- 6 followers