Catherine Sevenau's Blog: Writings~Rambles~Rhymes, page 65

March 20, 2015

A Chicken Named Blackie

1943 • Sonora, Tuolumne County, California

Our family lived at 104 Green Street, a white two-story house right in the center of town that rented for $35 a month, and where I would be born in five years. A wide porch ran on three sides. The back portion was enclosed and stored the mangle where Carleen ironed sheets and pillowcases, and where Mom had one of the first electric washers and dryers in town. Daddy put up pantry shelves with doors where Mom kept her canning: fruits from the trees in the yard, vegetables from her garden, field mushrooms (she and the kids hunted for them behind the hill at the grammar school), and her homemade spaghetti sauce and chili. The giant elm tree out front was a hundred years old with a canopy so thick that even when it poured you’d stay dry under it. To the left  flowed Sonora Creek, a small tributary of Wood’s Creek where the first big nuggets of gold were discovered in Sonora’s veins. It was filled with huge leopard frogs, rainbow trout, and wild blackberries until the early fifties, when that section of pristine waters was polluted and slick with oil and car fluids dumped directly into it through a waste pipe by mechanics from the Kelley’s Central Garage.

flowed Sonora Creek, a small tributary of Wood’s Creek where the first big nuggets of gold were discovered in Sonora’s veins. It was filled with huge leopard frogs, rainbow trout, and wild blackberries until the early fifties, when that section of pristine waters was polluted and slick with oil and car fluids dumped directly into it through a waste pipe by mechanics from the Kelley’s Central Garage.

rear: Larry and Carleen, front: Betty and Claudia, 1948, Yosemite

Out back, Mom raised chickens, the family’s source of meat during the war; she sold the eggs or traded them for flour and sugar. When Mom butchered the hens, it was Betty’s job to collect the chopped-off heads while the headless Leghorns chased Claudia who ran screaming around the yard. Mom put the bodies in a big pan of boiling water to soften the feathers, and Larry and Carleen had to pluck and clean them. Larry also had to clean the big metal chicken house out back, a job he hated more than anything.

You weren’t supposed to keep chickens if you lived inside the city limits, so if the roosters ever crowed before daybreak, Daddy went out and whacked off their heads. Each Thanksgiving they bought a live turkey, and Mom raised ducks too, but they flew away every year.

Betty was forever bringing home stray or wounded animals and hiding them under the porch. Our house was high off the ground and she kept her feral kittens hidden from Mom, spending months trying to tame them. Making a pond from the leaking well out front, she created a sanctuary for the pollywogs and tiny fish she toted up from the creek. Her only real pet was Blackie, one of the chickens. It had limber legs as a chick, and Betty begged Mom to let her keep it so the other chickens wouldn’t peck it to death. Mom finally said okay, she figured it was going to die soon anyway. It didn’t. Betty raised Blackie and kept her safe in its own little box, petting her soft brown feathers and clucking to her, training her by giving her water and grain several times a day from her hand. She loved Blackie.

One day Betty woke up with a sore throat. Mom cooked a big pot of chicken-rice soup for supper. Daddy, sitting at the head of the table, said grace: “Bless us Oh Lord…” When everyone raised their first spoonfuls to their mouth, Betty smelled something was off. “Where’s Blackie?” she asked. Mom and Daddy carefully studied the rice in their bowls, the other kids’ spoons dangled halfway to their mouths, their eyes lowered. Betty stiffened, shot a look at Mom, fell back from her chair and sprinted from the table, screaming “Nooo!” The rest of the family bolted down their supper. They were hungry.

March 13, 2015

Toss of the Cosmic Dice

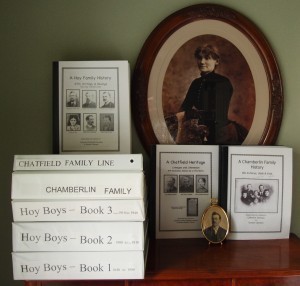

Why bother? I mean really? They’re dead. Who cares about the past, and what difference does it make? But here’s the deal, sometimes we do something for its own sake, or sometimes simply because we want to.

Why bother? I mean really? They’re dead. Who cares about the past, and what difference does it make? But here’s the deal, sometimes we do something for its own sake, or sometimes simply because we want to.

There was a five-year period from when I finished writing a family memoir until I published it. In that five years, I worked on my genealogy, gathering all the historical facts, figures, and tales I could glean about my parents and their lines. I didn’t plan on dancing with the dead any more than I planned on having teenagers or going into real estate. Sometimes things just happen.

Chamberlin sisters: Mamie Rosborough, Nellie Chatfield, Ada Whitaker

From adding flesh to the bones of our ancestors and breathing life into them as far back as I could reach, I came away with a sense of my genetic make-up. When I started this, I knew little beyond my grandparents’ names, then I came across a picture of my Grandma Nellie with her sisters. How could I not know that she had sisters? I nearly fell over, partly from realizing how clueless I was. but also how curious.

That’s what started me on the hunt. I spent untold hours on the computer (you have no idea) and tracked down other relations, all the while gathering pictures, records and letters. I now know my history and my heritage. I have a lot of the same traits and tendencies that those that came before me did. I gained insight about my culture. I came away with a love of history. I didn’t know squat about those that settled this country, about planters and pilgrims, about the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, or WWI and WWII. Did I sleep through high school history? I know I had the book as I carried that weight back and forth to school every day. Apparently I never opened it. My ancestors was part of all that, and somehow I’d missed it.

Actually, I find it stunning that I’m here at all. Truly, what are the odds? Simply because of a toss of the cosmic dice? First of all, each of those that came before me had to meet, then live long enough to procreate, then their children had to repeat that process: Peter Clemens, a stonemason, and his wife Mary Reiland arrived in New York from Luxembourg in 1855. George Chatfield (and his third wife, Isabel Nettleton) emigrated in 1639 from Sussex, England sailing on the ship St. John, and were of the original inhabitants of Guilford, New Haven Connecticut. Albrecht Hoy and Maria Schaurer left Prussia in 1751 to settle in Berks County, Pennsylvania. Henry Chamberlain V and his wife Susannah Hinds (their lines are from England) were born in Massachusetts in 1718 and 1722. Sebastian “Boston” Shade, an innkeeper and gristmill owner, was born in 1750 in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, His father, born in Bavaria, hailed from what is now Hessen, Germany; he was hired as a mercenary by the British government to aid in the rebellion of the colonists—then switched sides. That’s a long line of dead people who’ve been part of this country for generations, all of whom contributed to my very being. I stand on their shoulders, for if not for them, I wouldn’t be here.

Those of us that work on our family lines have an obsessive dedication and curiosity that surprises even us. It’s a remembering that’s important, offering an understanding of our imprint as a member of our culture and family, and who we are as human beings. Knowing where I came from reveals to me who I am. I’m blessed to one of the keepers of the lines, alongside my brother—who has been at it for years—along with a number of both near and distant cousins. It’s given me a relationship with them, among untold others, who’ve also shared what family information they possessed. Many with whom I connected were in their 80s and 90s; they were thrilled to talk to someone who was interested in their life, and generously shared their stories and pictures with me. They were also grateful to have a remembering of their past, and I’m thankful that they were able to share it with me before they died.

Those of us that work on our family lines have an obsessive dedication and curiosity that surprises even us. It’s a remembering that’s important, offering an understanding of our imprint as a member of our culture and family, and who we are as human beings. Knowing where I came from reveals to me who I am. I’m blessed to one of the keepers of the lines, alongside my brother—who has been at it for years—along with a number of both near and distant cousins. It’s given me a relationship with them, among untold others, who’ve also shared what family information they possessed. Many with whom I connected were in their 80s and 90s; they were thrilled to talk to someone who was interested in their life, and generously shared their stories and pictures with me. They were also grateful to have a remembering of their past, and I’m thankful that they were able to share it with me before they died.

Not everyone is fascinated by genealogy, particularly someone else’s. I’ve been to events where speakers rhapsodized at length about their kith and kin; it was painful, and, it was an “aha” moment. I realized we do all this work, and really, nobody else in the room gives a popcorn kernel! I discovered nothing bores me more than listening to the droning of another’s line, yet oddly enough, there’s nothing I like better than the puzzle of sorting out my own. I love the quest, and the satisfaction of having missing pieces fall into place. Gathering my kin also fulfills a need in me; it’s part of my wanting to keep the family together. I do it for my ancestors, I do it for my family still living, and for those yet to come. I do it because it’s important to me. That’s why I bother.

A smattering of lines:

Chatfield Heritage

Peter Clemens & Maria Reiland

Finley McClaren Chamberlin & Emily S. Hoy

Isaac Willard Chatfield & Eliza Harrington

March 7, 2015

The Sight of Blood

February 1950 • Sonora, California

Mom’s ham and cheese sandwiches were our favorite lunch. She ground the ham with her metal meat grinder, assembled and vise-locked onto the edge of the yellow Formica kitchen table. After filling the soft hot dog buns, she rolled them in waxed paper, twisted the ends, then heated them on a cookie sheet in the oven.

Mom’s ham and cheese sandwiches were our favorite lunch. She ground the ham with her metal meat grinder, assembled and vise-locked onto the edge of the yellow Formica kitchen table. After filling the soft hot dog buns, she rolled them in waxed paper, twisted the ends, then heated them on a cookie sheet in the oven.

One time, I was helping. I was a year-and-a-half, perched on the chair between my mother’s legs, my hand just big enough to fit through the opening into the metal housing, my finger pushing the meat in. Now the way these contraptions were constructed, you can’t take them apart when something gets ground in and jammed, you have to turn the handle in reverse to ungrind it.

Betty said I didn’t make a sound. My eyes grew huge, and I didn’t cry or move, I just turned ashen. My right index finger was jammed in the gear piece, ground tight with the metal blade cutting into the bone above the first joint. The handle wouldn’t budge. Mom and my sisters screamed, watching the blood running out the front of the grinder. The girls flew hysterically to the store for Daddy and he came home on a dead run. He unscrewed the grinder from the table, scooped me up, and sprinted to the Sonora Hospital with my finger still wedged in it and wrapped in blood-soaked towels. He handed me over to the doctor. The room began to spin, he broke out in a cold sweat, and then my father keeled over.

Betty said I didn’t make a sound. My eyes grew huge, and I didn’t cry or move, I just turned ashen. My right index finger was jammed in the gear piece, ground tight with the metal blade cutting into the bone above the first joint. The handle wouldn’t budge. Mom and my sisters screamed, watching the blood running out the front of the grinder. The girls flew hysterically to the store for Daddy and he came home on a dead run. He unscrewed the grinder from the table, scooped me up, and sprinted to the Sonora Hospital with my finger still wedged in it and wrapped in blood-soaked towels. He handed me over to the doctor. The room began to spin, he broke out in a cold sweat, and then my father keeled over.

Dad toppled when we had our tonsils out, when Carleen jumped off the back porch and ran a nail clear through her foot, and when she ran both arms through the wringer washing machine and her right arm broke; Mom had to hit the safety release to pull her out. He capsized when Carleen snapped her left arm bike riding; a friend had given it to her, but he neglected to mention it didn’t have any brakes. When she flew down a steep hill and couldn’t stop, she crashed and broke her arm. My father also passed out cold when she fell on her roller skates, breaking her right wrist while her arm was still in the cast. He was always able to get us to the hospital, but then he went down. The only living things he mortally harmed were the rooster that crowed at 4:00 a.m. and the dog he accidentally killed when he whacked it over the head with a shovel to stop it from killing the baby chicks; he fainted both those times, too. Daddy was only tough on the outside.

February 28, 2015

Midwestern Eyebrows and a California Thistle

Mom, Dad, Larry, Carleen

1937, Rochester

Dad’s first trip back to the family farm was for his mother’s funeral in 1937. He’d been gone from home for fifteen years, and had not spoken to her during that whole time; he was sure his Mother didn’t care about him. What he didn’t know is that she cried every day, hoping each time the phone rang that it was her son who’d run away to California, not even having told her good-bye. He and Mom took the long train trip east, bringing Larry who was almost four and Carleen who was two years younger. Farm kids were seldom catered to, and this woman from California indulged her children, especially Carleen, giving her daughter anything she wanted, the Minnesota relatives raising their mid-western eyebrows to one another.

Matt and Barbara Clemens, my father’s parents

Dad and Mom went back again in March of 1947 for his father’s funeral. During this trip Larry stayed with the Day family for three weeks, Carleen went to the Fouchs, and Betty and Claudia stayed with Uncle Charlie and Aunt Velma; it was the year before I was born. There wasn’t much to do on the farm and Mom, finally being free of her children, wanted to go, go go. Never wanting to sit still, she wanted to see the country, have some fun and kick up some dust. They visited her in-laws’ farms, meeting the whole Clemens clan of Dad’s eight brothers and sisters, aunts and uncles, nieces, nephews, and cousins, along with all the Conways and Nigons.

Discovering artichokes in the store one day, my mother excitedly bought a big bag full and cooked them for her husband’s family. They’d not heard of artichokes; Minnesotans ate red Jell-O and Rice Crispies bars, not fancy vegetables, much less thistles that were a lot of work for little sustenance, where you threw most of it to the hogs.

The family liked Mom. Well, the men and the kids liked Mom—her easy way and sense of humor. She had an air about her that made most of the women uneasy and she was not serious about duty. The farm women took care of duty, busy raising corn while my mother was out making hay. They lived the better part of their busy days in aprons and house dresses, wore sensible Red Wings or work boots, used no nail polish or make-up. They had chores to do, men to feed, and kids to care for—from dawn until ten and often back until dawn. It was noticeable that Mom was of a different flock. She dressed differently, sat differently, and spoke differently, was not as proper and reserved as they were—not as, one could say, buttoned up.

Clemens reunion, 1947, Rochester, Minnesota. Back row: Joe Clemens, Bill and Agnes (Clemens) Hauser, Betty Rose, Pearl and Lawrence Clemens, Amelia (Clemens) and Pat Conway, Frank and Mary (Clemens) Wallerich, Elizabeth Clemens; Front row: Betty Clemens, MaryLou Wallerich, Pat Conway, Jr., Noreen and Carl Clemens (my parents), Joe Wallerich

Dad’s siblings and their mates were at the reunion in Rochester in 1947. In the picture taken in the Terrace Room at the Oaks, a restaurant overlooking the Mississippi, my mother is front and middle, wearing a low cut black dress, legs easily crossed at the knee—not the ankle—sandwiched between a handsome uniformed Pat Conway, his arm draped casually over her shoulder, and Daddy, his hand discreetly tucked under hers. No, Babe was not a Minnesotan, and she was definitely not like the rest of the women in Dad’s family. Nor did she care to be.

***********

During the writing of these stories I asked Uncle Joe (my father’s youngest brother) what he remembered of Mom and he told me, “Well, she was nice enough.”

During the writing of these stories I asked Uncle Joe (my father’s youngest brother) what he remembered of Mom and he told me, “Well, she was nice enough.”

I asked what ‘nice enough’ meant.

“You know… nice enough.”

I said, “Nice enough… like what?”

“Well, she wasn’t bashful, quite the talker, and not afraid to tell people what she thought of them.” (My mother rarely had an unarticulated thought; everyone was entitled to her opinion.)

I persisted, “That doesn’t mean ‘nice enough’ to me. What exactly do you mean?”

He paused a long second and said, “Well, I guess you could say she was like a Monica Lewinsky nice enough.”

“Oh…” This was far more than I wanted to hear about my mother, lalalalalalalalala, ending our conversation.

February 20, 2015

Awaiting a Grandson

To my son Matt (who taught me about bandages, patience, and love) on his thirty-third birthday (1-14-2003) and who was awaiting the birth of his first child, a boy. That child—who is now nearly as tall as me, who can clean a fish, shoot a basket, and draw not only a cow but renders amazing dragons—is turning twelve in a wink and a smile.

There are useful things in life to teach a son—some taught by a father, some by a mother, some by others, and the rest learned by experience. Tradition once determined who taught what, and, traditions have changed.

Some things taught by a father perhaps:

To snap his fingers, whistle, and wink.

To shake hands, high-five, and bear hug.

To leave a dog alone that is sleeping or eating. To not eat the cat’s food.

How to throw a ball, swing a bat, shoot a basket, sink a putt.

To not leave tools in the driveway, in the garden, or in the rain.

How to build a fire. And split wood. And put up a tent.

How to bait a hook and catch a fish—and how to clean it too.

How to paint a fence, hammer a nail, saw a board, mow a lawn.

How to tie his shoes, peddle a bike, ride a horse, drive a car.

How to read a map, put in oil, change a tire, put on chains.

To plant a garden with carrots and tomatoes and basil and lovely fragrant sweet peas.

And from a mother perhaps (actually, my father taught me many of these):

To brush his teeth up and down. To wash his hands and wipe his feet.

To make his bed, wash the dishes, sweep the floor. To set the table, with napkins.

To pop popcorn and make spaghetti and bake Toll House cookies.

To sew a button and iron a shirt. To wash a load of clothes.

How to tell time and balance a checkbook. To write a thank you note.

To use a Kleenex and not his sleeve. That a clean tee-shirt is not formal attire.

How to draw a cow, shoot a camera, fold a crane.

Ladybugs aren’t mammals.

How to kiss a girl and how to slow dance. About birth, and birth control.

To say a prayer, sing a song, make a wish.

To smell the roses, to count the ants, to watch the stars. To notice the beauty of the moon.

And some things he’ll have to learn on his own, most the hard way:

Going to bed with gum in his mouth is bad for his hair.

To not put marbles, pennies, or Legos up his nose. To not eat sand or yellow snow.

To not wander away at the zoo, at the ocean, or in the city.

Vacuuming water out of the toilet is not a good idea.

Putting tweezers in an electrical outlet is a bad idea.

He’ll get in trouble with his teachers when the dog eats his homework.

His first girlfriend may break his heart; his second one too. And, he’ll be okay.

Bees sting. Cats scratch. Dogs bite.

Mice and hamsters and turtles and goldfish die.

To not dig up his buried pets a month later to see what they look like.

John Henry died, people we love die, we die. But not our souls; our souls don’t die.

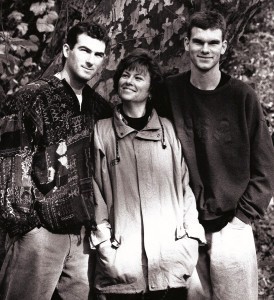

Matt, Catherine, Jon

Matt, you and your brother learned all this growing up, and these are the things your son will learn, and so much more. He’ll be as lucky to have you as a father as I am to have you and Jon as my sons. I love you, Mom

Catherine Sevenau

1-14-2003

February 14, 2015

Prologue to Behind These Doors

Audio: Prologue (click arrow to listen)

http://sevenau.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/1.-Prologue-Behind-These-Doors.mp3

My brother Larry was under the illusion that our mother was a good mother, but he had a different childhood than the rest of us. My sisters were convinced otherwise: Carleen complained Mom was thoughtless and self-centered, Betty resented her for abandoning us, and Claudia simply thought she was weak—all of which was true by the way. I was never under the illusion I had a bad mother, I was under the illusion I had the wrong mother, and although I was not under the illusion she loved me, I hoped she might someday. I was raised by omission, but neglect doesn’t leave a scar, it leaves a hole. Some say holes are harder to heal. Fortunately, I only lived with her from the time I was five until the age of nine. I figure that’s why I’m not completely neurotic. Or dead.

Clemens siblings, Sonora, California, 1950

L-R: Carleen, Claudia, Cathy (Catherine) in middle, Betty (Liz), Larry (Gordon)

I wrote our story, which evolved into a five-year journey. A magnitude of personal growth work put it into perspective; a writing class helped me get it down on paper. It’s about doors opened, closed, and locked, and about a family so complicated you’ll need a scorecard. As my friend Billy says, “There are really only five-hundred people on the planet, the rest are just crowd scenes done with mirrors.” It seems I’m friends with, or related to, most of these people. The rest I’ve dated.

My siblings loved my writing. Then a change of heart on my sister’s part, regarding something she said I could use, caused a major rift, so as not to be cast out, and to honor her wishes, I put the book away. For the next five years I worked on our genealogy. It was safer; they were all dead. My sister has since passed, along with enough time, so I returned to finishing “the book.”

What follows is what I’ve been told, what I recall, and what my family claims I’ve made up. Some stories I’ve never disclosed; some I’ve recounted so many times I can’t remember if they’re even true anymore. But do we ever recollect what actually happened? Certainly we remember our version—and what we believe is true for us, so we better be careful what we believe. And does any of it matter? Only when we make it mean something.

February 7, 2015

In Search of Funny

At a recent talk, a woman asked me about humor, and how do you learn to be funny. I said I don’t think you can learn to be funny. Either you are, or you aren’t. I told her I thought humor is often closely related to pain, that it arises as a reaction to suffering—like a coping mechanism—that sometimes it’s the only thing that gets us through this crazy life.

One can have a sense of humor and still not be funny; they don’t necessarily go hand-in-hand. Someone I know announced at a recent meeting that his New Year’s resolution was to be funny. My internal response was, “Good luck… that’s like me taking up jogging—we’re both going to make it about three seconds,” and continued, “and you’d better bring your lunch because you’re going to be here for a while.”

I’ve not met anyone with a normal happy childhood that’s really, really funny. I’m not even sure I’ve met anyone with a normal happy childhood; if they told me they did, I’d think they were very lucky, or lying. They’re pleasant, they’re kind, they have a sense of humor, but they’re not inherently funny. From what I’ve seen, most comics had challenging young lives, raised under difficult circumstances or suffered some sort of trauma. I think comedy often erupts from a deeper, darker place, offering healing to a wounded psyche. And, not everyone with a crappy childhood is funny: some turn out mean, others turn out sick, and more than a few become outright whack jobs. Then they blame it on their childhood.

Humor is subjective. I don’t get British humor; Monty Python doesn’t do it for me. I eye roll and yawn at movies that make others bust up, like Airplane, Dumb and Dumber, and Ace Ventura. I sit through them and go: really??? Racist and raunchy humor are also not my cup of tea. Corny doesn’t work for me either (unless you’re really old and remind me of my father), nor do lame Hallmark cards or sappy love songs. I get that humor is in the eye of the beholder. I tilt to the dry and the absurd, to irony and satire. I loved Groundhog Day, Blazing Saddles, and Harold and Maude. Jon Stewart, Tina Fey, Robin Williams crack me up. Bob Newhart cracks me up. I even crack me up, but I’m easy.

I’m funny—not because I’m inherently disturbed, though that may be—but that because if I didn’t laugh, I’d cry. When I was a child I’d burst into tears if anyone looked at me cross-eyed. I was crushed by the slightest criticism and cried when my sisters made fun of me. I sobbed through Disney movies, and Bambi nearly did me in. The female tongues in my family flick with meanness, and as I was over-sensitive and dorky to begin with, I had to toughen up to survive. I can still be a dork, which oddly enough has generated some of my best stories and most hysterical moments. I don’t know what happens, it’s like I become possessed, confused, or indignant, and then the moment gets hold of me and snowballs downhill from there. Of course those standing by slither away, pretending like they’ve never seen me before. My response (after I’ve felt bad if I’ve hurt someone’s feelings) is usually: ah, to heck with ‘em if they can’t take a joke.

I’m funny—not because I’m inherently disturbed, though that may be—but that because if I didn’t laugh, I’d cry. When I was a child I’d burst into tears if anyone looked at me cross-eyed. I was crushed by the slightest criticism and cried when my sisters made fun of me. I sobbed through Disney movies, and Bambi nearly did me in. The female tongues in my family flick with meanness, and as I was over-sensitive and dorky to begin with, I had to toughen up to survive. I can still be a dork, which oddly enough has generated some of my best stories and most hysterical moments. I don’t know what happens, it’s like I become possessed, confused, or indignant, and then the moment gets hold of me and snowballs downhill from there. Of course those standing by slither away, pretending like they’ve never seen me before. My response (after I’ve felt bad if I’ve hurt someone’s feelings) is usually: ah, to heck with ‘em if they can’t take a joke.

A fine crack within me separates my laughter and pain, my humor and hurt; with time, events on one side of the crack seep over to the other, and with perspective, the ability to filter the pain or hurt through humor makes life bearable. Unless I haven’t eaten, then all bets are off.

There are occasions I get hooked… where things happen and I lose my sense of humor. I attended an Angeles Arrien lecture in Santa Rosa during a time when my younger son had a bug up his butt and wasn’t speaking to me. She was talking about clarity, objectivity, discernment, and humor, all qualities embedded in the archetype of wisdom. I’d done a lot of personal growth work, seen more about myself than I’d ever in a day cared to see, and one thing that still pained me was my relationship with my son, and there was not one iota of humor in there. I knew it was bringing to the surface all my mother stuff about being ignored and not cared about, and really didn’t have much to do with him, but it still had me by the throat. No matter how I attempted to work it out or tried to let it go, the more entangled I got—like Br’er Rabbit and the Tar Baby. At the end of her talk she took questions from the room. I stood up in front of a couple hundred people and said, “I’m stuck here. I have a son who’s not spoken to me for the last three years, and it’s killing me. And you know what, I just don’t find it very f****n’ funny.” The whole room cracked up. Angeles looked at me in kindness and said, “Like that. Look, I get it. But until you get some distance from this, some humor, you will stay stuck.” Her response settled me some, but it took me a couple more years to get there. Today, my son and I are on good terms, but I still find it difficult to go in there and find the humor from that time. Maybe I still need a bit more distance, or, maybe I just need to lighten up.

Despite the chaos, sadness, and anger swirling around in the world, I do think what goes on is generally funny. It’s like some large cosmic joke, like, you know, woe! Life is funny like that. Except when it’s not. But laughter is basic, not to mention healing; it takes the edge off, lightens your load, improves your mood, and stimulates the immune system. It’s a lot like good sex, except you don’t catch any diseases.

I only know one joke, about a string that walks into a bar, but I screw it up every time I tell it.

To me, this is funny; I so wish I’d written it:

“With all the sadness and trauma going on in the world at the moment, it is worth reflecting on the death of a very important person, which almost went unnoticed last week. Larry LaPrise, the man who wrote “The Hokey Pokey,” died peacefully at age 93. The most traumatic part for his family was getting him into the coffin. They put his left leg in… and then the trouble started.”

February 1, 2015

A Dream Story

Many of my past dreams, the ones I remembered and wrote down anyway, are of me trying to get somewhere, usually on some odd form of transportation, not knowing how to get there, and often with people following me who think I actually know where I’m going. In one I’m riding a horse, leading the way; in another I’m in an English taxi; in one rolling along in a wheelchair; another on stilts, one on a tricycle, another on a bicycle, and in one dream I’m pedaling away in a Pedi cab with a group tagging along behind me.

Many of my past dreams, the ones I remembered and wrote down anyway, are of me trying to get somewhere, usually on some odd form of transportation, not knowing how to get there, and often with people following me who think I actually know where I’m going. In one I’m riding a horse, leading the way; in another I’m in an English taxi; in one rolling along in a wheelchair; another on stilts, one on a tricycle, another on a bicycle, and in one dream I’m pedaling away in a Pedi cab with a group tagging along behind me.

One night, just prior to falling asleep, I asked my mother, my father, and my teacher Michael Naumer (all deceased) to come to me in my dreams. I recorded the vivid succession of images in a journal as soon as I awoke (October 22, 2002). The dream started with Michael (who’d been gone five months). That part was short, and the only thing I remember was asking him if there was something he wanted to tell me, or if there was anything I needed to know. I tried to listen to what he had to say, but my attention kept wandering, so I don’t know if he answered, or, I didn’t hear him if he did. The images shifted to my mother (who’d taken her life some three decades before):

I’m at the San Francisco side of the Golden Gate Bridge just past the tollbooth in the slow lane, weaving in and out of traffic, lying face down on an old wooden go-cart that looks like a kid’s snow sled with wheels, moving along quickly, making it go faster with my hands and feet. A nicely-dressed attractive woman with straight shoulder-length blonde hair is walking just behind me and calls to get my attention. “What does she want?” I think. I’ve traveled a good distance, and have no time to talk; I’m trying to get someplace. I ignore her and she calls out again. I race away, lying prone on my vehicle, my face just inches from the pavement rapidly passing beneath me, and weave my way from the slow lane onto the pedestrian lane. She’s still following me.

Moon Valley School reunion, mid 1980s: Audrey, Charlie, Moona, Catherine, Barbara, my son Matt

I lose her. In the next instant I’m in front of the house next to the Sebastiani Winery (which is three blocks from where I live), scooting along behind the bushes in case she’s still nearby. When I’m sure the coast is clear, I pick up my go-cart and step carefully down the moss-covered stone steps. The next instant I am carrying it through a market in the tree-covered plaza (which is also three blocks away). As I wend my way through the bazaar, I notice the beautiful stalls look like many I’ve visited in the town plazas in Mexico, the papayas, oranges, and onions stacked in perfect pyramids surrounded by buckets of tied stock, irises, and sunflowers: colorful and fragrant. I find myself standing in front of a corner fruit and flower stand where three friends, Moona, Audrey, and Barbara, are showing and selling their artwork from their booth. (These three women are just a few years older, about the ages of my three sisters, and were a comfort and inspiration when I first moved to Sonoma. They were involved as parents or teachers in Moon Valley School, a small alternative school run by Charlie Price where I sent my sons in the mid to late 1970s, where I became the bookkeeper, and then ran the school for a few years after they’d all moved on. Audrey, Moona, and Barbara were also single mothers who gave me courage around raising two young boys on my own.)

Audrey holds up a piece of her work. “It’s beautiful, but I don’t have time, I’m looking for this place.” She telepathically knows where I mean, and points. It’s just around the corner. Three bungalows, white, clean, and crisp—like little connected beach houses each with one small window and a screened front door—are to my left. I sense my mother is inside the first one on my right. I see the door is open through the screen. I lean my go-cart against the wall, peer in, and in the far corner I see my mother asleep. She looks to be in her mid-forties and I’m a young teenager, the ages we were the last time we saw one another.

It’s light and bright in there and I’m surprised she doesn’t have on her eye-mask. I’m nervous about coming in as I’m sweaty and covered in dust from the road. The room is small and clean, crowded with a few pieces of furniture and barely any space to walk. A single white-sheeted twin bed is next to her, there is a round white table and a small white upholstered chair; everything is white, white, white. I’m quiet and tentative, not feeling very sure of myself, wanting to see and talk to hear, but waiting for her invitation. She waves me over to her bed. “Come sit next to me.” Taking off my jeans so as not to get her bed dirty, I sit with her. I notice she has tubes everywhere: an IV in her arm, a plastic one up her nose and down her throat, a catheter coming out of her. She’s ill and I realize she’s dying. While she shifts to make herself comfortable, I look around the room and see six or seven framed photos on a tall oak bookshelf near the door. I’m curious if any of them are of me. They are all family pictures and we look happy. We aren’t all together, but in photos by ourselves and a couple with two or three of us posing together. My mother is not in any of them, I’m in three. One close-up by myself—my first or second grade school picture—only I have a on hat like a bonnet with a small brim. I think how sweet I was as a child, how fresh and pretty. A second picture is of me and Daddy. The third, I don’t recollect who all was in it, but there are several of us. I study them, relieved she has pictures of me. She did care about me. My attention turns to her, and I ask, “Is there anything you’d like to tell me, anything you’d like me to know?” At that instant, I wake up.

The next day (in my everyday waking life) I find in my mailbox a postcard from Barbara, announcing she is giving now Tarot readings. Dialing her, I say, “I just got your card and this is so weird… last night I had the most vivid dream that you were in.”

“You always want to tell people when you dream of them,” she says, “as it’s significant when we dream about one another.”

“Want to hear it?” When I finish the rather long details, she tells me, “I’m part of a dream circle that meets once a month, and the woman who designed and facilitates dream circles and published a book about them is coming up from Los Angeles to be there. Would you like to come?”

I don’t know much about dreams, but believe they can have significance, and as this one was so detailed, I wanted help to decipher what it meant. “Absolutely,” I said, “When and where?”

A week later I join Barbra and a circle of women, some of whom I’ve met, others I’ve not. My friend Daphne comes with me as she is interested too. We’re waiting for the dream woman, Connie Kaplan, to arrive. When she comes, Daphne and I are introduced and Connie, an attractive normal looking blonde, sits next to me on the couch. She checks in with everyone, tells a story, and then relates a second one of her avoiding serious injury in a four-car collision on the freeway coming up from Southern California. I’m looking at her profile, and as she says “freeway” and turns her face toward me a little, all the hairs stand up on my arms and the back of my neck.

“You’re the blonde in my dream,” I interject.

Laughing, she says, “Well, you may have been dreaming me to protect me in the accident. Thank you.” Then she tells us a story about angels walking through walls, being given messages from the other side, about her experience with the angles at the time of her father’s death—all a little far-fetched for my money—however…

The dream circle begins, along with the passing of the talking stick from woman to woman. I find the process interesting. I’m dying to ask Connie about mine, but I’d been told before the circle began that I may not share as I’m not a member of the group.

When the evening concludes, Connie and I talk outside where I relay my dream to her. At the end, she asks me a couple of questions, then says, “Many dreams have a pun, and the most interesting part of your dream, to me, is your pun: it is where you take off your jeans.” I don’t get her point. She goes on, “If it were my dream (that’s what one says so as not to splash the dreamer with an opinion, but what the dream might mean personally to the person commenting), I would say that in that action I’m changing the genetic patterns in my family.” She looks at me quizzically, and then says, “You’re the only one doing work in your family, and you can do that you know.”

And in that moment, something inside told me that this woman, whom I’d met in a dream, was telling me the truth.

January 24, 2015

Smoke Gets in Your Eyes

Audio: Smoke Gets in Your Eyes

http://sevenau.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/15.-Smoke-Gets-in-Your-Eyes-•-1959-La-Habra.mp3

Smoke Gets in Your Eyes • 1959, La Habra, California

Sequestered by the murky outline of the San Gabriel Mountains, Orange County had constant smog alerts, sometimes so bad they closed the schools. Everyone was told to stay indoors, the outside smothered in a pea soup of brown haze so dense not even a Santa Anna wind could blow it away.

The pall enveloping our card games was worse than the pall outside. Carleen inhaled Pall Malls and Claudia smoked Salems. Betty preferred Parliaments, and when she full of herself, she smoked Vogues. She smoked two, three, sometimes four packs a day, blowing me perfect smoke rings whenever I asked. In those days, everyone smoked: Ricky and Lucy, John Wayne, Grace Kelly, Ed Sullivan, Liberace, my sixth grade teacher Mrs. Wilcox, my mother, and my three sisters.

I was happiest when playing cards with my sisters. The four of us sat at the dining table for hours, their oldest kids locked outside the front screen door to play in the neighborhood, the babies in the playpens napping while we shuffled, cut, and dealt. They let me play because they needed a fourth for partner Hearts, Canasta, or Pinochle. I didn’t interfere with their conversation and I laughed at their jokes, which were over my head. I ingratiated myself by serving them ham sandwiches, refilling coffee, lighting their cigarettes, and emptying ashtrays. Some weekends we’d be at it all day and all night, only taking breaks to feed the kids. Betty lost a babysitter once because she didn’t make it home until dawn. “One more hand,” we’d say, “just one more hand.”

Clemens siblings: Carleen, Claudia, Liz “Betty,” Gordon “Larry,” Cathy, April 1959, La Habra

They drank pot after pot of coffee and smoked pack after pack of filters, complaining the whole time how crappy their hands were, bad-mouthing Mother, and bitching about their husbands. I was clear that I did not like coffee or cigarettes, clear that I was not going to grow up to be like Mom, and really clear I wasn’t going to marry some s.o.b. like they had.

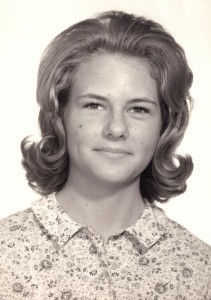

Cathy, 5th grade, La Habra

Playing a game of Hearts, I carefully organized my cards by suit and value, alternating the reds and blacks, trying not to drop any face up on the table, when it dawned on me what I had. I held the Queen of Spades, all the high hearts, and enough lower ones to shoot the moon. Yabba dabba doo!

“Yessss!” I hid my crooked grin behind my fanned cards, so excited I could barely contain myself, my brown cowlicks and peepers popping with glee.

“Whooeee!” I slapped my free hand on the table.

“Yaahooo!” my butt cheeks danced on the chair.

“Oh yeahhh!”

Swearing, the three of them threw in their cards and didn’t let me play my hand.

“I hate you!” I whined.

“Oh shut up and shuffle,” they replied.

There’s nothing like a common enemy to unite sisters, and we had Mom. Our Mother’s redeeming value though was, she played cards. When she pulled up in her black-and-white Buick Special with the four chrome holes on its sides, we readied ourselves. Carleen and Betty said they didn’t like being stuck with her as a partner either, but since “either” had to go to school during the day, they tolerated her as my fill-in. They cheated when they played with Mom, slightly fanning their cards to each other, quietly passing under the table whatever they needed to fill out their hand. Mom wasn’t as sharp as she once was. Her thinking ability was fuzzy from shock treatments and the pills that she took, and my sisters took full advantage. Whenever they talked about Mom, they referred to her as your mother, like she wasn’t their mother, just mine.

There’s nothing like a common enemy to unite sisters, and we had Mom. Our Mother’s redeeming value though was, she played cards. When she pulled up in her black-and-white Buick Special with the four chrome holes on its sides, we readied ourselves. Carleen and Betty said they didn’t like being stuck with her as a partner either, but since “either” had to go to school during the day, they tolerated her as my fill-in. They cheated when they played with Mom, slightly fanning their cards to each other, quietly passing under the table whatever they needed to fill out their hand. Mom wasn’t as sharp as she once was. Her thinking ability was fuzzy from shock treatments and the pills that she took, and my sisters took full advantage. Whenever they talked about Mom, they referred to her as your mother, like she wasn’t their mother, just mine.

I learned a lot more from playing cards than just shuffling, cutting, and dealing. Like how to win and how to lose. I realized that pouting didn’t improve my hand one whit. I got the hang of the rules, how to keep score, and how to count. I learned how to bluff. I mastered keeping my cards close to my chest, when to hold ’em, and when to fold ’em. I learned to lead with my strong suits, and to play my bad cards as well as I could. I got cheating wasn’t fair, or all that much fun. I learned to play the cards dealt me even when they were rotten, and that it was only a game and not to take it too seriously. I learned about the Ace of Hearts and the Queen of Spades, and that hearts trump everything and hope trumps anything. And I learned that there was always a new hand soon to be dealt, and possibly, a better one.

January 16, 2015

“Let’s Take a Trip Down Whittier Blvd!”

1961 – 1966 • La Habra High School

Four years of high school blended together, being neither the low nor high point of my life. The second tallest girl my freshman year at La Habra High, I tripped up and down the long halls between classes praying to be invisible, hoping no one would look at me, especially the boys. Math was not my strong suit and I nearly flunked algebra. I hiked three miles to and from school every day, uphill, both ways; it was easier to walk than to roust Carleen out of bed that early in the morning to get her to take me.

My sophomore year was slightly better, as was my confidence—even though my face was spattered with pimples and moles, I still made most of my clothes, and they switched my picture with another girl’s in the yearbook. I had Sally and Laura to eat lunch with in the cafeteria or out in the quad. I took Russian in the morning before first period, still having to make that hike back and forth. My junior year was a definite improvement. Laura got a brand new gold 1964 Pontiac LeMans for her sixteenth birthday, and every morning, she drove from her house in Whittier, a ways out of her way, to my house on Verdugo Ave., picked me up, and drove me home when school got out; I loved her for that, more than she’ll ever know. Kay, Linda, Laura, Peggy, and I had a car club, the Shalimar’s, even though only Laura had a car. We’d started our own as the cheerleaders didn’t invite us into theirs.

My sophomore year was slightly better, as was my confidence—even though my face was spattered with pimples and moles, I still made most of my clothes, and they switched my picture with another girl’s in the yearbook. I had Sally and Laura to eat lunch with in the cafeteria or out in the quad. I took Russian in the morning before first period, still having to make that hike back and forth. My junior year was a definite improvement. Laura got a brand new gold 1964 Pontiac LeMans for her sixteenth birthday, and every morning, she drove from her house in Whittier, a ways out of her way, to my house on Verdugo Ave., picked me up, and drove me home when school got out; I loved her for that, more than she’ll ever know. Kay, Linda, Laura, Peggy, and I had a car club, the Shalimar’s, even though only Laura had a car. We’d started our own as the cheerleaders didn’t invite us into theirs.

I had a summer boyfriend, Bob, who liked me, and who, of course, Daddy didn’t like. Bob’s father, a sergeant on the San Francisco Police Force, fixed all his speeding tickets. His mother held his hand until he was twelve. A Mission Dolores and Riordan boy who lived in the Parkside, he attended San Francisco State, worked three jobs, lived at home with his family, was my stepsister Irene’s husband’s younger brother, and wrote me letters signed, keep good thoughts. I was in love.

For the first time in my life I felt like I fit in. I no longer cared that I may have been the only person in my high school of 3,000 students who lived with a family that had a different last name, whose parents were divorced and married five times between the two of them, whose mother was in and out of asylums. It didn’t matter that I was almost 5’10, that my capped front tooth didn’t match my other teeth, that I wore a padded bra. It was alright that I wasn’t a straight-A student, that I was terrified to stand up front in speech class, that I wasn’t a sosh, a cheerleader, or class anything. None of that was important any more. I was finally okay, just the way I was.

By my third year of Russian class, I could remember the letters of the alphabet. Laura continued ferrying me to and from school. I had girlfriends, and was allowed to cruise Whittier Blvd. on Friday nights with them as long as I was home by ten. We’d grab a burger at Bob’s Big Boy, then go lowriding with the windows rolled down and the music cranked up, California girls flirting with the passing boys, bobbing our heads to the the Byrds and Beatles, the Righteous Brothers and Beach Boys. “Ba ba ba, ba Barbara Ann…”

By my third year of Russian class, I could remember the letters of the alphabet. Laura continued ferrying me to and from school. I had girlfriends, and was allowed to cruise Whittier Blvd. on Friday nights with them as long as I was home by ten. We’d grab a burger at Bob’s Big Boy, then go lowriding with the windows rolled down and the music cranked up, California girls flirting with the passing boys, bobbing our heads to the the Byrds and Beatles, the Righteous Brothers and Beach Boys. “Ba ba ba, ba Barbara Ann…”

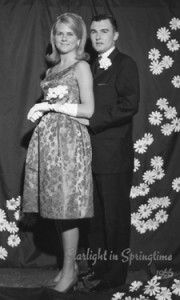

Bob took me to the Springtime Ball and my Senior Prom. I received a small high-school scholarship to San Jose State. My capped tooth had broken off again; excused to go to the dentist, I was more than greatly relieved to not to have to stand up in front of the whole auditorium to accept it. They gave me the money anyway. I got the scholarship because Mrs. Brown, my business class and typing teacher who’d taken me under her wing, recommended me. When the school counselor interviewed me to see if I qualified (it certainly wasn’t based on grades as I was only a “B” student, at best), I felt awkward when she asked about my family, and why I lived with my sister. I didn’t mention my home situation to anyone, except a few girl friends. She asked if my sisters were as pretty as me. I hesitated, then told her no. None of us were particularly pretty—we were just normal looking. I was glad that it ended the interview, but always felt bad that I said they weren’t, like I betrayed them or something.

(Excerpt from the complete memoir of Behind These Doors: A Family Memoir)

Writings~Rambles~Rhymes

- Catherine Sevenau's profile

- 6 followers