Catherine Sevenau's Blog: Writings~Rambles~Rhymes, page 60

June 9, 2016

What I Remember

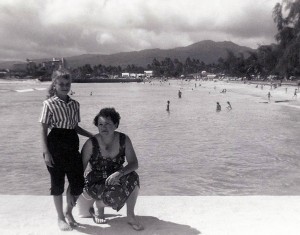

Mom, Bobby, me, Bishop Museum, Oahu, Jan 1958

1958, Honolulu, Hawaii ~

I had a crush on Bobby. He was blonde, tan, and handsome; a Georgia cracker with a slow Southern drawl and a boyish, white-toothed grin, a swabbie in navy blues or crisp white bell-bottoms. He was 19 and in his third year in the Navy, married to my sister, who was 15 and pregnant with their first child. When he was transferred to Oahu, Mom and I moved to paradise sometime in November of 1957 to be near Claudia. They lived in a small studio apartment on the second floor of the WWII barracks in Waikiki. Of course I had a crush on Bobby: he was cute, he was nice, and he was the only one who paid any attention to me.

In mid April I had another vomiting spell and had to be hospitalized again, the seven days of absence marked on my Manoa Elementary 4th grade report card. Mom told the doctor I had a history of throwing up. He thought it might be emotional, and suggested she have me see a psychiatrist. She also told him I was jumpy as a water bug. I was always tripping or falling down; my skinned knees and scraped elbows had scabs on scabs, my stubbed toes were forever covered with dirty Band-Aids hanging on for dear life. On top of that, she told him I was now having nightmares.

Cathy on Easter Sunday, April 6, 1958

It was on a Saturday afternoon in April, the day before Easter, that it happened. It came up in the psychiatrist’s office. Sitting in a leather chair next to him, not too close though, we looked at pictures. One by one, he handed me images of moths from a folder, asking me what they looked like. I carefully handed them back, one by one, saying they looked like moths. Then Dr. Whateverhisnamewas invited me to play with toys in a tabletop sandbox. I did, but didn’t see the fun of it. Miniature soldiers and plastic animals didn’t interest me. I no longer played with toys. He asked me to draw my family, which was complicated because Mom and I lived in the hills in Manoa and Claudia and Bobby lived near the beach, Daddy lived in San Francisco, and Carleen, Chuck, and Debbie lived in Whittier. Larry and Marian lived in Long Beach, and when Mom and I left, Betty stayed behind in San Jose. I didn’t count Ray or Irene because they weren’t really related to me, and how was I supposed to fit all this on one sheet of white paper?

The therapist asked me questions, but I don’t recollect telling him much. He met with Mom after my appointment. He told her that the absence of a stable, consistent home life might be the cause of my repeated vomiting spells. It would be better for me if I could stay in one place for a while. He also told her about my crush on Bobby, and about my nightmares of a man waiting for me at the top of the stairs with a gun in his hand, and that I couldn’t see the man’s face. Maybe the bad dreams did have something to do with Bobby, but I didn’t tell him about what happened that day in the apartment. I didn’t tell him because at 9 years old I didn’t know what had happened, didn’t know how to put it in words. Besides, Bobby made me promise. So I never told anyone—not for 35 years.

But I remember that Saturday afternoon with Bobby. I don’t know where Mom and Claudia were, probably at the commissary for groceries or cigarettes. He and I were alone in their one-room apartment. He was propped up with pillows at the head of the bed. I sat cross-legged on the corner of it, shuffling cards, hoping he’d be up for a few games. He was. I beat him three times at Go-fish and he beat me once at War. Then he said he was tired and wanted to take a nap and would I like to crawl under the sheet and snuggle?

I said, “Sure.”

He brushed my hair away from my face. We cuddled. He ran his hand up and down my back. But when his hands slipped around my waist and I felt the elastic stretch as he pulled at my pants, I tried swimming backwards off the mattress as he slid my pants down. He held on to me, his breath rolling over my hair.

“Please, Bobby no. Let go. I’m not tired.” He was whispering but I couldn’t understand what he was saying. “Let me go, please. I have to pee bad, Bobby, really bad. Please. Please. Let. Me. Go.”

“Jes be still a minit,” he said. “’Kay girl, ’kay? Jes for a minit.” And that’s about all it took.

He let me go. I cleaned myself up on the toilet, clammy and confused, then pulled up my blue peddle-pushers while he stood next to me and washed his hands at the sink.

“Y’all er fine, girl. Y’all ain’t hurt,” he said quietly, looking in the mirror. “Ain’t no need tell ‘bout this. Be our secret, alrite?”

I slipped out of the bathroom and tiptoed outside, leaving him there. Frozen midway on the metal staircase that bridged the yard to the apartment, my world shrank to one step, the red sun in the sky slowly sinking, neighbor kids laughing and playing with a puppy below, Bobby in the apartment above. I waited, suspended in bewilderment and worry. I was grateful for his attention, but something happened in there. Something divided me, something I didn’t understand, done by someone I loved.

With my head whirling, my stomach chewing, and my feet cemented to that grated step, I was unable to move in either direction. I tucked all my confusion and sadness into my stomach along with all my feelings about my mother, about Hawaii, about Bobby. I slipped in all my fear of pain and being sick, my homesickness for Betty and Carleen, my wanting to be with Daddy. I didn’t know where else to put it.

I waited there for Claudia and my mother to come, wishing I were anywhere but here. By the time they showed up, the sinking ball of fire had slid into the ocean and it was nearly dark.

It was not so much what happened with Bobby that dented me—it’s that he’d been my only friend. I no longer went near him. I no longer went in their upstairs #5 apartment with the Murphy bed when he was there alone in his white Hanes undershirt and jockeys. I still liked him; I just didn’t get near him. I didn’t get near other men after that either, especially ones that talked slow and quiet, in a sing-songy, Mr. Rogers kind of voice, like maybe you were dense or retarded or something.

I also remember sometime later, on a clear Friday afternoon, a girl and I were playing the cigarette game on our way home from school, racing and keeping score of who stomped first on the empty packs of Kents, Kools, and Lucky Strikes that littered the roadside. She was older, a fifth grader.

“I bet you don’t know what sex is,” she said.

Shaking my head, I told her I didn’t. From the look on her face, it didn’t sound like a good thing.

“Want me to tell you?”

“Okay.”

“It means sticking his up hers.”

“What?” I had no idea what she was talking about. “Stick his what up her what?” She spelled it out for me. It stopped me dead on an empty flattened red and white pack of Winstons. I had her tell me again. I’d never heard such a thing, and was sure she was making it up. Until it sank in.

So that’s what happened. I still couldn’t make any sense of it, but at least now I had a word for it. I thought about it for the rest of the day, until the final scraps of light were gone, until it was the time when I no longer said my prayers, the time to climb into bed with the silent back of my mother before me.

And that’s just one of the things I remember about living in paradise.

Note: This is an unpublished excerpt from the full manuscript of Behind These Doors, A Family Memoir.

June 2, 2016

Holy Cards, Hell, and High Water

(listen to audio)

http://sevenau.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/7.-Holy-Cards-Hell-and-High-Water-•-1949-Sonora.mp3

Summer 1949, Sonora, California ~

Sonora was a backwater with no Catholic school, so every summer five young Franciscan nuns in black habits and white wimples were imported to bring the schoolchildren a proper Catholic education. The Sisters did their best to inoculate the youngsters, dispensing a heaping dose of guilt to tide them over to the next summer. Larry, Carleen, and Betty had already built up an immunity; the majority of the teachings simply washed over them like a fine, quickly evaporating mist. Claudia was still impressionable, taking all the teachings to heart.

During catechism, as rewards for knowing the right answers, the nuns gave out felt scapulars and scores of holy cards. Claudia collected the most, knowing nearly all the answers. She took no duplicates, “no, I already have that one, thank you.” She wore her scapular every day. After a month, when the felt strap and backing got too ratty, the Sacred Heart of Mary and the face of Christ looking upwards towards God, were carefully folded and tucked away in her underwear drawer.

During catechism, as rewards for knowing the right answers, the nuns gave out felt scapulars and scores of holy cards. Claudia collected the most, knowing nearly all the answers. She took no duplicates, “no, I already have that one, thank you.” She wore her scapular every day. After a month, when the felt strap and backing got too ratty, the Sacred Heart of Mary and the face of Christ looking upwards towards God, were carefully folded and tucked away in her underwear drawer.

In the beginning, Claudia was a believer, but by the third grade, skepticism was gaining ground. During catechism she had many questions:

“How could the blood and body of Christ be in a wafer that came in a box from the post office? Would you really get blood in your mouth if you bit into one? How come only men get to be priests? Did God say that?

She didn’t get any satisfactory answers, other than somehow most of this was Eve’s fault: our downfall began with her. The explanations she gleaned from the nuns were, “some things you simply have to take on faith,” or “it is a mystery; no one knows the answer,” responses which simply increased her confusion. When she double-checked with Mom, her comeback was generally, “Well, that’s just the way it is.”

One day a nun stopped Claudia and patted her eight-year-old head as she came out of the Sonora Library. “What a pious child you are!” Sister Bernadette beamed at her. “You’ll grow up and be a perfect nun.“

One day a nun stopped Claudia and patted her eight-year-old head as she came out of the Sonora Library. “What a pious child you are!” Sister Bernadette beamed at her. “You’ll grow up and be a perfect nun.“

Alarmed, Claudia ran home and tore through the screen door. “I have to be a nun!” she cried. “I don’t want to be a nun!” Throwing herself against Mother, she relayed what Sister had said.

“Oh, for the love of God, Claudia, you don’t have to be a nun,” Mom pooh-poohed, much to Claudia’s great relief. “You can be whatever you want to be when you grow up. Now go outside. I’m trying to get dinner on.”

Mother spent much of her time countermanding what the church professed.

“Don’t be ridiculous, you’re not going to hell if you eat meat on Friday,” she’d snort, cleaning her glasses and shaking her head.

“No, you won’t go to hell if you don’t go to Mass on Sunday,” throwing her arms in the air in disdain. “And no, you won’t go to hell if you walk into a Protestant church.

“But those are all mortal sins!” Claudia cried, “Like murder!”

Mom clamped her hands on both hips in scorn. “That’s all a crock of hooey!”

“But they said… ” my sister wailed in response.

“Oh for heaven’s sake, Claudia,” and mother, rolling her eyes, launched into another exposition on hell, high water, and common sense.

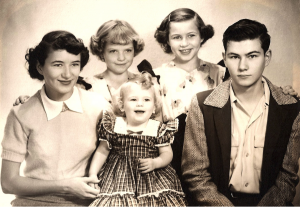

May 26, 2016

Beginnings and Endings

December 1952, Sonora, California

Clemens siblings, Sonora, California, 1950

Carleen, Claudia, Cathy in middle, Betty, Larry

Carleen snapped at us. “For the umpteenth time, I don’t know why she left, when we’ll see her again, or where she went, and no, I don’t know if she’s coming back. Now don’t ask any more questions!” Mom was gone, and this time, Carleen knew she wasn’t coming back. My sister was in charge now and there was no need to discuss it further.

The first time our mother left was in April of 1950, before I was two. Claudia was seven years older than I was, so that made her eight; Betty was ten, Carleen was fifteen, and Larry sixteen.

Our lives continued. Spring faded. Summer passed. Fall blew into winter. Mom once returned for a week, wept the whole time she was home, then fled again. She came back a few times more, but knew she couldn’t live a life she didn’t want. She told Larry she didn’t know what to do, that she’d go crazy if she didn’t get away, that she had to leave.

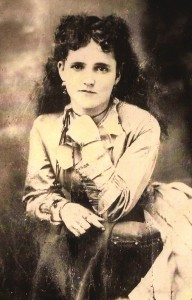

our mother, Noreen Clemens

A lot happened in the family during that time; Daddy could no longer hold his head up in town, kids were told not to play with my sisters, and people whispered. Some of it had to do with sex, the very thing my father couldn’t tolerate, especially when it had to do with anyone in the family.

Finally, in 1952, packing what she could carry in two suitcases, she left for good. Mothers didn’t run away in those days—except ours did—and Betty never forgave her.

Even though she hated Mom, Betty was miserable without her. She didn’t want to go to school and constantly complained that her throat hurt, so after several weeks of too many absences, Daddy decided she needed her tonsils out. When summer arrived, it was time.

Carleen woke us up on Tuesday and told us to get dressed. That day, Claudia was signed up for a novice tennis tournament sponsored by the recreation department. Carleen told her she wasn’t going to be able to play, we were going somewhere with Daddy. She didn’t tell us where. When we drove up to the Columbia Way Hospital, Daddy was waiting at the entrance. He informed us we were having our tonsils taken out.

“Since Betty needs hers out, you two might as well have yours removed, too.”

“Who’s first?” The nurse asked.

Betty and Claudia glanced at each other, then in unison pointed to me. My not quite four-year-old body was packed up and carried howling down the short corridor, my sisters listening to my screams. My wailing was muffled as I was strapped to the bed, then silent from the metal cone of ether held over my face. Claudia was next.

When we all came to, we were told not to throw up or cough because we could bleed to death, as if we had a choice about not throwing up. Of course we all threw up, and did so for days afterwards, sick from the ether, certain we were going to die and wishing we would. It took me the longest to recover.

That was the beginning of my several hospital stays, and the end of Claudia’s tennis career.

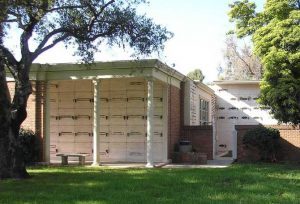

May 19, 2016

On the Woo-Woo Side

Two events occurred on my trip to Southern California that might catch your attention. The first was at the funeral for Kay’s (a high  school friend) mom. Family and friends drove in caravan with a police escort to the cemetery after the service at the Mormon Church up the road. As I’m standing behind where the family is seated, I notice “Memory Garden” imprinted at the top of the shade tent. I ask Kay’s cousin standing next to me, “What town are we in?” He says “Brea.” I turn to him and out of my mouth comes, “My mother is buried in this cemetery,” and I look behind us at the buildings on the hill, “up there.”

school friend) mom. Family and friends drove in caravan with a police escort to the cemetery after the service at the Mormon Church up the road. As I’m standing behind where the family is seated, I notice “Memory Garden” imprinted at the top of the shade tent. I ask Kay’s cousin standing next to me, “What town are we in?” He says “Brea.” I turn to him and out of my mouth comes, “My mother is buried in this cemetery,” and I look behind us at the buildings on the hill, “up there.”

I was at Memory Garden in 1968 when my siblings and I gathered to inter my mother’s ashes, and again with my brother a dozen years ago when I was working on a family memoir. Considering who I am in the world, I’m amazed that I somehow sensed where I was. I took leave of the group and slipped away for a moment to find her niche, way up high on a wall. I snapped a picture and asked her to watch over Kay’s mom, now that they were neighbors, and to intervene on my behalf with whoever is mad at me on the other side that keeps holding up the finishing of my book.

I was at Memory Garden in 1968 when my siblings and I gathered to inter my mother’s ashes, and again with my brother a dozen years ago when I was working on a family memoir. Considering who I am in the world, I’m amazed that I somehow sensed where I was. I took leave of the group and slipped away for a moment to find her niche, way up high on a wall. I snapped a picture and asked her to watch over Kay’s mom, now that they were neighbors, and to intervene on my behalf with whoever is mad at me on the other side that keeps holding up the finishing of my book.

After the reception I headed two hours north to Camarillo where I was spending the night at my cousin’s, a Chatfield (my grandfather Isaac W. Chatfield was her grandmother’s brother). Joanne (age 89) had fallen on her patio nine months ago, cracking her head on the cement, was taken to the hospital, and never came home. While in recovery she broke her leg tumbling out of her wheelchair, then dementia crept in and stole her mind, too. I was staying with her husband, Lee (also age 89). He sits with her, heartbroken, for three hours every other day as she lies in bed staring at the ceiling, her one broken leg bent crookedly over the other.

Joanne had pictures of our ancestors that I’d seen from a prior visit that Lee was letting me borrow. The only one we couldn’t find was a 6 x 14 inch sepia on cardboard (circa 1890) of her grandfather, Josiah Small, in a Civil War re-enactment. It was not in the boxes we’d gone through.

In the nine months that Joanne had been in the hospital, bills, letters, and magazines had accumulated, taking over their dining room, piled on the table, chairs and floor. I needed a bigger envelope to fit some of the larger pictures in, and Lee went into the garage to look for one. Next to me on the chair about an inch down in a foot high stack, I spotted a thin brown bag that they’d fit in. I slipped it out, hoping it was empty, but found two pictures in it. One of them… hang on… was the missing Josiah Small. It was a Kinko’s bag, and on the pictures was a sticky note with my email address. Joanne fell before she could get them to me.

I’d no inkling about that bag, any more than I had a sense in the beginning that I was in the cemetery where my mother was—but these things happen to me, especially around working on our genealogy or writing my book. I’m quietly led to the next piece I need, and out of the ethers, it appears. It’s like a cosmic consciousness opens and allows me in. It used to weird me out, but I’ve learned not to question grace; now I simply bow to the mystery of it all, filled with awe and appreciation.

September, 2014

May 12, 2016

Private Matters

Grandma Nellie

My father was German and my mother English, which could explain everything. On my dad’s side I’m a generation removed from hardworking, church-going, duty-bound dairy farmers. On my mother’s I come from freewheeling, drinking, smoking, gambling, hell-raising cattle ranchers with a couple of righteous Catholics thrown in for some temperance. I happen to know my maternal relatives had more fun; I can tell from their stories. Most of them didn’t see much value in being good except my Grandma Nellie Chatfield, who was of the opinion that rectitude was required behavior, and the higher she stood on her moral ground, the lower her family descended. I tend to take after Nellie and my father’s side of the family. How unfortunate for me, and for those around me, especially those who tend not to behave.

Noreen, my mother

I imagine it’s no coincidence that my writing began when I was 53, the same age my mother was when she called it a day. Nor that it took me five years to write our chronicles, the same amount of time I lived with her when I was a kid. I have a suspicion she’s had a hand in this whole thing, directing from the ethers, enjoying having her story told. She would have LOVED all the attention. My father, on the other hand, would have cautioned me to keep much of what I wrote behind closed doors. He was a private man, of the generation that didn’t discuss affairs of the family, money, or sex.

Dredging up some of these stories was a cross between Groundhog Day and post-traumatic stress syndrome. It’s amazing how long the shelf life is on the defining moments that smack us as kids. They’re like Wonder Bread: always fresh.

I made it through my childhood, then I lived through five years of writing about it, which was at times as anxiety producing as experiencing some of it the first time around. My right shoulder froze, then my left, my stomach wasn’t happy, nor was my sister, and I had three computer crashes. In the last one I lost my motherboard. Now what are the odds of that? I didn’t even know a computer had a motherboard.

Cathy and Noreen 1957

when we lived in Hawaii

My mother is still with me; I’m continually bowled over how I manage to recreate her in so many of my relationships. The bane of my existence and my greatest teacher, she is a gift that keeps on giving.

May 6, 2016

To My Wife-In-Law

Matt and Jon

Rebecca, the best thing that happened to our family was you. How could I not care for someone who loved my children as much as I. You became my wife-in-law and the boys’ other mother. You filled in pieces that Bob and I didn’t have the ability to bring. I became the father and you, the mother. You brought the fun, the Easter baskets, and laughter. I brought the rules, household chores, and curfews.

You made sure I got child support, and when you learned I was getting $150 a month, you had Bob double it, and a few years later, double it again. You were a much better wife to Bob than I ever could have been. You had patience and a way with him that I did not. You worked around him. I butted up against him, busily making him incompetent and wrong; we only made it for five years. You remained married to him for eighteen, and now that you are remarried with a child of your own, your new family has become part of ours.

In the beginning, you worked with Bob at the carpet store, and then moved in with him. You were good to the kids. At a time in my life when I was trying to get Country Fresh started, I went to you and asked if you would take Jon for me, just for a while, just until I could get my feet on the ground, and I would like to see him every weekend and please make it okay for him and that it would just be temporary. Matt was starting at Moon Valley School, so he was taken care of during the day.

The hardest thing I’ve ever done was parting with Jon for those two months. It was so painful for both of us. It was too hard to say goodbye and bring him back or visit him each weekend, so my visits got further apart. You drove him to My School in the morning and when you got to the Washoe House, the two of you would sing, “Wash your hands, wash your face, wash yourself at the Washoe House.” You couldn’t tell me how much he missed me because you knew it would break my heart.

He still had ear infections, and they got worse. Just to prove a point, Bob gave him milk because Bob didn’t believe that both the boys were lactose intolerant. Each time they stayed with you and Bob, they’d come home with a cold followed by an ear infection. You said, “Well, Bob is Bob,” and never expected him to behave any differently.

When Jon was in the seventh grade and Matt a freshman in high school, you planned a trip for the five of us to Mexico.

“Are you nuts? I’m not spending three weeks with Bob, nor am I interested in sharing a hotel room with two teenagers for that length of time. I don’t like kids that age.”

“Come on, it will be fun,” you said. “Bob will lie on the beach and drink beer all day, the boys can play basketball and fish, and we can shop and sightsee,” you said. “We’ll spend Christmas and New Years in Oaxaca for the festivals, then we’ll hang out on the beaches of Zihuatanejo and Ixtapa through New Year’s. We’ll have a great time,” you said.

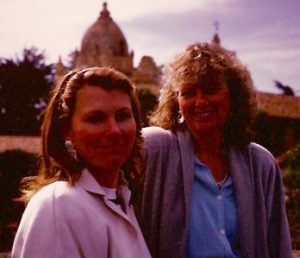

Rebecca and Catherine, Mexico

You talked all of us into it. Then it dawned on me what people would think.

“Look Bob, when people ask, say I’m your sister. They aren’t going to get this otherwise. It will be easy, we all have the same last name.”

One Southern woman travelling with her two granddaughters got wise, however. After watching and listening to us for a bit, she arched her eyebrows and drawled, “Well now, just how are all of you related?”

I looked her in the eye, raised one eyebrow, and drawled back, “Bah marriage.”

We sat in the bleachers together at the boys’ baseball and basketball games. You bought them matching cowboy shirts, helped with their college, and stood with us when Matt got married. We spent nearly every holiday together. You live in Canada now, too far for frequent visits, but close enough to be in my heart.

In 1993, I did the Sterling Women’s Weekend. You did too. So did my friend Cindy, along with Kristin, Barbara, both Shirleys, Kathy, Jean, Mary, Julie, Lisa, and about fifty other women I knew. We have many women in our lives. After doing that weekend, I understood why I’m not married. And don’t intend to be. I do better in my working relationships with men, and have had five great work husbands over the years: Art, Ron, Michael, and two Charlies. I helped run an alternative school, I took on the role of managing and partnering in two real estate companies, and assisted in two long-term coaching endeavors. I had boyfriends to sleep with, quite a few over the years, so it seems. I didn’t have to marry someone just to have sex. I did that once.

Rebecca & Catherine, Florence

In the summer of 1994, you and I traveled to Italy with Sandra and her family. We rented a car to meet them in Florence. I was in charge of the map. Florence was in big letters, but the road signs all said Firenze. After circling the city for an hour, you figured it out. A few days later we hooked up with Matt in Milan. He’d been traveling for several months after graduating college, and when we met up with him, he’d been hitchhiking for days. The hotel nearly didn’t let him in because he looked like a vagrant. He was happy to see us and even happier for a bed and a shower. We hiked Cinque Terre, ate pasta and clams to die for, and shopped the flea markets. Shopping rules, according to the boys: “It has to be fragile, expensive, bulky, heavy, and totally useless.” Sandra and I wanted to buy a matching pair of bronze angels that weighed a ton, but we didn’t have enough lire on us and her mother wouldn’t lend us any money; she thought it was a ridiculous purchase. You bought a complete set of dishes from Deruta and had them shipped home. When you split up with Bob, he got the credit card bill and you got the dishes: I thought you were brilliant. When I split, I got the kids, a 1950 Dodge pickup, and the red couch from Mexico. I’d have rather had the dishes… and the kids, of course.

Matt, Jon, Rebecca, Becky, Dennis, Lesley in front

You left Bob shortly after that trip, but remained a part of our family. You asked me to stand as your witness when you married Dennis. The small town of Ridgecrest, where you both grew up, was a bubble of a bowling-alley-and-beer mentality, and your friends couldn’t wrap their arms around that one. You had Lesley soon after. She was adorable and funny. I put ice cubes down the back of her jammies. She called me Cathysevenau, as if that was my first name.

Rebecca and Bob

Jon, Matt, Catherine

We have Christmas with your new family and you have Thanksgiving with us. Bob comes, too. You share your mother, Pat, with me. At my Thanksgiving table one year, Bob was at one end, I was at the other, and seated on one side were you, Dennis, Pat, Lesley, and your brother. On the opposite side were Matt and Jon, my niece Julie, Dennis’ daughter Becky, and Bob’s fourth wife. Bob started in on the embezzler in the family (who was not present) and I held up my hand like a traffic cop at a crosswalk, “Look, it’s Thanksgiving. Could we not do this at the dinner table?”

He stabs his fork in the air and says, “Oh, so you live in some fairyland and think time heals all wounds?”

I paused two beats and retorted, “Well, darling, you certainly wouldn’t be sitting here if I didn’t.”

Everyone busted up, especially Pat, who thought Bob had said, “So you think time wounds all heels?” This made everyone except Bob laugh even harder, since in this case, it was pretty much the same thing.

Was that the year that Pat suggested we order the whole kit and caboodle at Safeway and go for a hike Thanksgiving morning instead?

I was shocked. “Can we do that?”

“Of course we can,” she said.

Your mother had style. We ordered it the day before and picked up everything that morning: stuffed turkey, mashed potatoes, gravy, green beans with onion rings, sweet potatoes, cranberry sauce, pineapple and marshmallow salad, and three pies. Then we hid the boxes, and no one knew. The boys went on and on, saying it was the best Thanksgiving dinner I’d ever made.

When your brother died, the pastor failed to show, so you asked me to take his place. I was so nervous that I can’t remember how it went, other than looking for support at the woman in the back coordinating the microphone and giving me hand directions as to what to do next, watching your mother nodding in grief, and everyone crying, I spoke about him as best I could. I think it went okay.

When your mother was dying, you called and asked me to come immediately, to be with you both at the hospital in Palm Springs. It was too big for you to do by yourself. I was there within hours. I sat with Pat to give you a break. We held hands and looked into one another’s eyes and communicated with finger pressures, saying we loved each other and that it was okay and not to be scared. You were her hospital advocate, and one of your biggest concerns was that in more than a week she’d not had a bowel movement. When I returned home a couple of days later, Lesley called in great relief.

“She pooped!” It was headline news.

You brought me friendship, support, and love. You kept Bob out of my hair. You loved our sons. The only time you ever got mad at me was when we were on a street corner in Spain, you were studying the map, and I asked you which way we were going. You snapped, “How the f*** would I know? We’ve only been here two hours. Why am I always in charge of the directions?”

Tearing up, I said, “Well, I don’t think you want me to be in charge.” It was my birthday that day, and at lunch, you apologized and gave me a pair of gold angel earrings.

Catherine and Rebecca, April 2016

Thank goodness you were in our life while the boys were growing up. Between the two of us, we made a good mother. I am grateful that you are still in my life! We’ve been related for more than forty years. When it’s time to leave, maybe we do it together, giving each other a last smooch and going over the cliff like Thelma and Louise or Butch and the Sundance Kid. Although, as I’m not all that adventuresome, maybe we just call it a day, have one last cup of tea and a cookie, kiss one another goodbye, and turn out the lights.

April 28, 2016

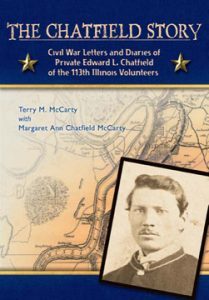

The Chatfield Story

The flood of memories, the details of countless events recalled at late evening fireside, the myriad of horrid private images never shared with anyone—we can only begin to imagine how this original O’Dea Andersonville Lithograph worked the mind of Kankakee’s Edward L. Chatfield from the 1885 date he bought it until his 1924 death at 82.

Edward Livingston Chatfield

Apr 17, 1863

Edward L. Chatfield was born 400 miles east of Kankakee—in Middlefield, Ohio, in 1842. He came to Kankakee as a 17-year-old, the eldest of seven, thriving on 172 acres of Pilot Township’s fertile soil. It was here in Kankakee that Ed honed his early skills in masonry—assisting his dad to build the Chatfield Stone House still standing eight miles west of town on Hwy 17.

Heeding Lincoln’s 1862 call for 300,000 three-year volunteers, Chatfield enlisted August 5, 1862, assigned to Co. B, 113th Illinois Volunteers. He regularly wrote home, maintaining three diaries while fighting in the Battles of Chickasaw Bayou, Arkansas Post, Vicksburg, and Brice’s Crossroads. He survived disease and imprisonment at Andersonville, Savanna, Millen, and Florence—all before he escaped! His letters and diaries tell the full story.

Un-cloaking this Lithograph in Arizona

The year was 1964. Peg’s cousin, Edaline (Chatfield) Rhea, had passed away earlier that summer. She was the only child of Edward Livingston Chatfield, the namesake of this book. Edaline had hidden something for safekeeping before she died, and the secret of its location was lost with her. The executor’s phone call invited Peg’s family to retrieve personal family items, and the two of us made the long hot drive from Los Angeles in earnest. ….

Against the back wall of the slender bedroom closet stood a rolled 40” x 60” lithograph of Thomas O’Dea’s famous picture of the Andersonville Prison—a bird’s eye view of the stockade and its surroundings, with perimeter pictures depicting prison events, including, in one of them, six men hanging from a beam. Thomas O’Dea, a captured private of Co. E 16th Regiment Maine Infantry, sketched the images from memory between 1879 and 1885. His original pencil sketch measured 4.5 x 9 feet. Chatfield’s lithograph copy had been etched on stone by T.J.S. Landis circa 1885, and distributed by Henry Seibert & Bros., a reduction measuring 39 7/8 X 60 ¼ inches.

~Terry McCarty and “Peg” Chatfield-McCarty, April, 2016

From Andersonville, visions of hell on Earth

“Thomas O’Dea survived the harrowing conditions of the Confederate prison Andersonville before coming to Cohoes [NY] and sketching a famous drawing of the misery he endured there. O’Dea was a 19th-century Renaissance man who went from Irish immigrant to prisoner of war to labor leader to successful artist and businessman… [having created] an imposing 4 1/2-by-9-foot pencil sketch [of] Camp Sumter prison in Andersonville, GA, …the large bird’s-eye, panoramic view of the camp, along with 20 surrounding vignettes depicting disease, hunger and death within the prison’s walls.

Thomas O’Dea

O’Dea was a proud man who felt some of the first accounts from Andersonville inadequately captured its history. O’Dea started drawing in 1879 after seeing a report that portrayed the prison as orderly. He worked nearly six painstaking years, mostly at night after long days of laying bricks. His images of near-naked men in excrement, stacked dead bodies, and up to 35,000 desperate prisoners from August 1864 struck a nerve in the wounded nation, especially with veterans from the North. “It was the only visual that could express everything that had occurred in the camp,” Perreault said.

O’Dea sailed from Ireland with his family and settled in Boston as a young child. Turned away by the military as a 14-year-old, he ran away and joined the 16th Regiment of the Maine Infantry Volunteers in July 1863, about halfway through the war. O’Dea fought under Gen. Ulysses Grant in Virginia during the Battle of the Wilderness. He was captured in May 1864 and moved around Confederate prisons until he arrived at Andersonville in the summer of 1864.

Confederate forces built the prison in south central Georgia as their fortunes in the war sagged. The facility was meant to hold 10,000 men. Food and medicine were scarce, and the only source of water was a stream that also served as a bath and sewer.

Prisoners lived under the sun without barracks or tents. Order broke down. Roving gangs attacked and robbed other inmates. Those sick with dysentery, gangrene and other illnesses fell across the camp. Hungry Confederate officers stole food meant for prisoners. Nearly 13,000 prisoners died during the 15 months the camp operated.

O’Dea’s captors released him from Andersonville on Feb. 24, 1865. He left ill and emaciated, wearing only ragged trousers and broken shoes. He returned to Boston after months of recuperation, but his family had disappeared. He moved to Cohoes in the early 1870s and worked as a mason. He was elected general secretary of the Bricklayers and Stone Masons Union of America and the Cohoes Board of supervisors.

In the following years, Andersonville bombarded the nation’s psyche through photos and novels, but most of all, O’Dea’s drawing. Included in it were portraits of himself and Father Peter Whalen, a Catholic priest from Ireland who ministered to all at Andersonville. The poster became such a success that O’Dea set up a business and sold 10,000 lithograph copies for up to $5 each.

Thomas O’Dea Lithograph of Andersonville Prison

By 1887, the mason worker had moved from Summit Street in the town’s mill section to the more fashionable Walnut Street, and listed his job as “author and proprietor of O’Dea’s famous pictures of Andersonville Prison.” Reprints flourished across the nation and became the inspiration for poems. A copy of the drawing eventually landed in Aurora. Ill., which led O’Dea to reunite with his brother George after 25 years. He never found his sister or parents. O’Dea returned to Andersonville for a week stay in May 1914, the 50th anniversary of his capture. … O’Dea and his wife, Catharine McGuinnes O’Dea, had five children. Thomas O’Dea died March 18, 1926, and is buried with his wife and four of their children in St. Agnes Cemetery.”

(Excerpts–“From Andersonville, visions of hell on Earth,” by Dennis Yusko, crediting Paul Perreault, Malta Town Historian, for the story. www.Timesunion.com, May 6, 2012

From Terry and Peg Chatfield-McCarty: Catherine, here’s the news on Ed Chatfield’s treasured documents:

From Terry and Peg Chatfield-McCarty: Catherine, here’s the news on Ed Chatfield’s treasured documents:

1. Chatfield’s Civil War letters—more 100 original letters and related artifacts largely presented in The Chatfield Story—moved from our guardianship to that of San Marino California’s Huntington Museum on December 22, 2015, bolstering the Huntington’s impressive collection of correspondence from the common soldier. It was difficult to part with these treasures after having guarded them for fifty-one years, but we were thrilled with the knowledge that they are now preserved for the long-term and can viewed by the inquiring public for centuries to come.

2. Likewise, Chatfield’s personal original copy of the impressive O’Dea Lithograph of Andersonville—the notorious Georgia Civil War Prison Camp—transcended to the guardianship of Illinois’ Kankakee County Museum on April 19, only days ago. Again we are thrilled that this important piece of history is now assured prolonged protection and frequent public viewing.

Thomas O’Dea 1848 – 1926, Find A Grave memorial page

Edward Livingston Chatfield 1842 – 1924, Find A Grave memorial page

The Chatfield Story, by Terry M. McCarty and Margaret Ann “Peg” (Chatfield) McCarty

April 14, 2016

Perms

Carleen always gave us a Toni the day before school pictures; she was making us beautiful. She shampooed us, yanked our snarls, swore at us to quit sniveling, then sat us in a row at the yellow Formica kitchen table. With old bath towels draped over our shoulders, Betty, Claudia and I perched on the matching vinyl chairs, waiting our turn. Carleen scotch-taped our wet bangs to our foreheads, then with Mom’s good sewing scissors, snipped them straight across. Starting at the crowns of our heads, she carefully wrapped each combed lock with a little white square of tissue paper, then tightly rolled it in pink plastic rods, ordering us to, “sit still and quit whining.” Finally, she poured the processing solution over our heads, tilting her head sideways so she wouldn’t pass out from the reek of ammonia. We held the cotton strips tight to our forehead so we wouldn’t go blind.

By morning, our bangs had shrunk three inches above our eyebrows, four inches where the cowlicks were. Flat on top, the rest of our hair was so tight and curly it stuck out in triangles on each side like Bozo the Clown, but one side was always higher than the other, so it looked like our hair was on crooked. We also stank to high heaven for a week.

Betty Clemens 1951

Claudia Clemens 1951

Cathy Clemens 1958

Cathy Clemens 1954

One year, the year I was six and Carleen wasn’t around, Mom put Betty and Claudia in charge of my hair. Leaving the barbershop in tears, my sisters made me trail ten feet behind, saying I looked like a boy and so ugly they couldn’t be seen with me, laughing and taunting, “we don’t even know you” and calling me a “poor little orphan girl.”

However, I think my hair did look better in my school picture that year.

April 8, 2016

Emily and Those Hoy Boys

Emily S. Hoy, 1867

As rivers cut canyons through Rockies to bays

the Hoys traveled westward in pioneer days.

They fought for the Union

(Frank, wounded in battle),

Then homesteaded Brown’s Hole

where they branded their cattle.

They were ranchers and farmers and bull-whackers of yore,

horse breeders, schoolteachers, and miners of ore.

They were writers and poets, a politic few,

they were German and English, a Swiss woman too.

Herein are their timelines, their letters and lore,

with charts of our ancestors and children they bore.

Newspaper clippings, records, and wills,

excerpts and photos and warranty bills.

They all tell this history so much better than I,

this trail left behind from those now all gone by.

I penned stories of kin my brother explored,

he combed through the records—such tasks I deplore.

Names, facts, and figures, they interest me some,

but tis the echoes of tales that I yearn to plumb.

The Hoys sued each other, Grandpa gambled the ranch

(he, a fool with the whiskey—an ache through our branch).

Davis cheated on Emily and cared not the least,

Ada’s vows to Doc Chambers were undone by the priest.

J.S. while in France was castrated with knife,

caught in the act with a med student’s wife!

James perished from poison! Tracy shot Val and ran!

Harry fasted five weeks—up and died from that plan.

The query that actually started this game

was, “What’s the “S.” stand for in Emily’s name?”

Some mysteries still linger, some relations not found,

like what caused Frank’s death and where laid in the ground?

What happened to Winnie? From what did she perish?

A tintype of her I truly would cherish!

A.A. had three daughters—what happened to them?

And what of wife Frances—his crème de le crème?

There’s no trace of Lizzie, in shadow she’s sunk…

disappeared like Minerva and J.S.’ trunk!

Missing records and pictures and letters of yore

keep me digging and searching—I know there are more!

One more trip, one more hunt, another call I will make

just to find out for clarity’s sake.

But does it matter if I know not all that occurred?

No, though at the end of the day you may rest assured

that I’ll let out a whoop and drop down on my knees

if I ever discover the answers to these!

Catherine Frances (Clemens) Sevenau, 2006

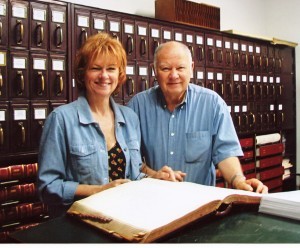

Catherine and brother Gordon, doing family research in Sanders, Montana 2006

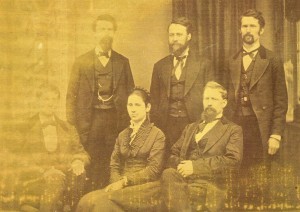

Hoy siblings, circa 1873

back row: J.S., Valentine, Adea

front: Harry, Emily (my g-grandmother), Frank

April 1, 2016

Credo For Today

How shall I live my life? Where do I stand? When do I speak out?

CREDO FOR TODAY

Ten Commitments

1. I shall honor Spirit: my God, your God, their gods, and the god within me.

2. I shall honor my word, and take responsibility for what I speak.

3. I shall rest, honoring a Sabbath time.

4. I shall honor my family, my community, and my beloved biosphere.

5. I shall honor my capacity to kill—and have the common sense, wisdom, and compassion to not commit such an act.

6. I shall honor my sexuality, committing no offense.

7. I shall not steal.

8. I shall tell the truth—and endeavor not to add to chaos, war, or misery.

9. I shall govern my envy of others, refusing to let it dictate my behavior.

10. I shall be grateful, to humbly bow and kneel to the beauty and mystery of it all.

Ten Reminders

1. Clean up my inner litter; this includes not dumping it in my neighbors yard.

2. Quit carping and complaining, raining my misery on others.

3. Let go of my personal hurts; stop nursing them as if they were my only children.

4. I am not the center of the universe; life is not all about me and what I want.

5. I am connected and interconnected with everything. What I do matters.

6. Accept all of myself, and all of you—our greatness and our pettiness.

7. Be of service to others, and to something greater than myself.

8. Loosen my attachments: to being right, to being liked, to being perfect.

9. Listen to and trust my inner voice, my inner wisdom, and the wisdom of my body.

10. Befriend death and dying.

[image error]

“Creation” mandala by Michael Naumer

medium: chalk pastels

Why Am I Here? Perhaps …

I am here to wake up.

I am here to be useful.

I am here to be happy.

I am here to make a difference.

I am here to work out my spiritual dilemmas.

I am here to love.

I am here to create.

I am here to be in this miraculous yet ordinary body.

I am here to realize my birthright as an evolving being.

I am here to remember who I am.

Catherine Sevenau, 2006

Writings~Rambles~Rhymes

- Catherine Sevenau's profile

- 6 followers