Catherine Sevenau's Blog: Writings~Rambles~Rhymes, page 59

August 4, 2016

No Room for Cowards

July 28, 2016

Princess Imelda

July 20, 2016

Determining Our Life’s Path

July 14, 2016

How Hard Could It Be?

July 8, 2016

An “Incident” Revealed

June 30, 2016

A Defining Moment

Our Incident

June 23, 2016

My Impending Demise

We think we have time. The question is, “how much?” That leads to other questions. Will I be satisfied with how I lived my life? What is it I’d like to complete before I die? What will I leave behind?

I recently attended my cousin’s funeral. She was 81. Her son said, “I assumed we’d have another ten years with her; I was wrong.” Odds are good that I’ll live to my mid-80s or 90s. Odds are equally as good that I won’t. Things happen. If my math is correct, I have 57 first cousins (born from 1920 to 1959), 22 of whom have died. I’m the youngest of the brood on my Chatfield side, and eighth youngest on the Clemens. As the deaths of this generation occur with increasing regularity, my impending demise moves to the forefront of my imagination.

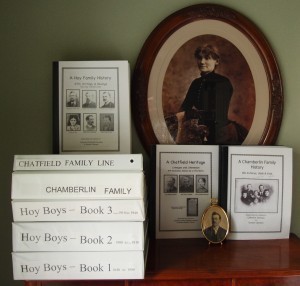

Chatfield, Chamberlin and Hoy Genealogy

Responses to my three questions:

1. Will I be satisfied with how I lived my life? For the most part. I’ve participated in the creation of two children, two grandchildren, and three successful businesses. I’ve helped hundreds of friends and clients buy and sell their homes, and in that process was intimately a part of their lives. I’ve contributed my time and abilities to teachers, organizations, my community, and schools. I’ve written and published two books, compiled a number of genealogies, and provided a vast amount of genealogical information on line. I’ve had the courage and tenacity to play big in some arenas. I’ve cleaned up the majority of my inner litter. Willing to reveal myself, I’m willing to talk about things others won’t, to be an example of another way to do it. Much of what I’ve imparted to others—both in business, personal transformation, and in my writing—has made a difference, and a part of me remains with those that allowed me to contribute to them. Luckily, I have friends and family who care about me. I would die bereft if I thought no one cared, that there was no intimacy, no love in my life. I know what that feels like; it’s painful. My mother died like that; the choices she made throughout her life confirmed the way she died. .

2. What would I like to do before I die? I don’t have much on my to-do list other than returning old family pictures loaned to me, dealing with the thousands of genealogy correspondence in my inbox (this one may be complete fantasy on my part), and completing and publishing a family memoir that I started 15 years ago. I’d also write a book on the specific childhood event that forms who we are and what we become, our “incident.” It would be stories about “where we are the most wounded, we are the most accomplished.” I’ve heard and worked with hundreds of people and helped ferret out their defining moments, and it’s a fascinating study. I think I have time, but we know how that goes. Who knows what will befall me or when my time will come. While I still have some stamina and most of my marbles, I might want to get crackin’ on these things. I don’t have a lot of loose ends, unrealized hopes, relationships that need cleaning up, or ironing to do before I go. Actually—other than my garage—my past, present, and future are in pretty good shape, all things considered. It’s not my nature to be messy so this doesn’t surprise me. If I have time to complete my wish list, I’ll take care them, If I don’t, I won’t.

G-G-Grandfather, Saints Peter and Paul Cemetery, Mazeppa, MN

3. What will I leave behind? A documented chronicle of our family legacy reaching back to the time our ancestors came to this country. For seven-some years I’ve compiled over 7,000 pages on-line of those I am related to by blood or marriage, and a few are on there to whom I’m related to by grace. I hope I’ve loosened some of the anger and angst that afflicts so many in my family, both living and dead. I’ve diluted the resentment I bring to the party. I’ll leave behind my consciousness, my humor, and my wisdom; I wrote it all down for those who are interested. I’ll leave behind the sagacity, the acute mental discernment and soundness of judgment my teachers imparted to me, as I’ve paid that knowing forward. Unless I have a giant garage sale, I’ll also be leaving behind a lot of stuff; things I’ve loved and enjoyed over the years, but things I won’t take with me. If I don’t outlive my money, I’ll leave what’s left of that too.

Am I afraid to die? I’ve no idea. It’s an “in the moment” process, mysterious and profound, and I don’t know that any of us knows how much grace, or dis-grace, will cling to us when we die. I suppose part of it depends upon the circumstances. I have little guilt gripping me, I’m no longer weighted by the shame I‘ve carried, and I’m not holding onto unspoken words. Well, I’ve some, but speaking them wouldn’t be worth the fallout. It’s fine to leave some things unsaid. Besides, it’s my stuff, not theirs.

Third Eye Chakra, Mandala Healing Art by Sarah Niebank

I don’t believe that death is “it.” I’m curious to see if those who’ve passed before me will be there to greet me. I wonder if my consciousness will be able to connect to the earthly plane. I’ve felt others who have passed connect with me, so why won’t my energy be able to do that? Will I still have work to do on the other side? Is there another side? Maybe I’ll go to Arcturas and search for my cousin Aura. That’s where she came from, and where she returned when she died. Will I re-incarnate? Does karma play into any of it? Will I get another chance, a do-over? Will I return with more work to do around my mother? I mean really, enough is enough already.

As I age, I see how fleeting my life has been. The older I get, the faster it goes. In ten years I’ll be nearly 78. It will likely be harder to roll out of bed in the morning, more challenging to keep up with my grandchildren who will nearly be adults themselves by then, and impossible for me to get to Carnegie Hall, no matter how much I practice. I’m not as caught up in everything as I used to be; it takes too much energy to maintain that stride. I like this pace of slowing down. Time is an illusion, but it gives a sense to living. So in this moment, I have time.

June 16, 2016

Elegy to My Father

1905 – 1986

Born on a Minnesota farm, you milked cows, picked corn, and shocked wheat. You hated farming; that’s why you left Minnesota, that, and your mother always telling you what to do. She cried when you left home; you were only sixteen. You had nine siblings, all with the same Clemens nose; your sisters looked like you in a wig. As a boy, you walked three miles to and from school in the snow—uphill—both ways.

Mom was 17 and you were 27 (and a virgin) when you married. You were 43 when I, the youngest of your five children, was born. In Sonora you were a storeowner and town councilman: a big fish in a small sea. Things changed. Never speaking of Mom after she left, you told me not to either. You lost your business, your family, and your pride, paid your debts and left town.

You ate bottles of aspirin and rolls of Tums. When I was sick, you rubbed Vicks on my chest, gave me two Aspergum, and stroked my forehead. Sitting on the edge of my bed, you had tears in your eyes as you remembered the only time your mother comforted you was when you were sick. You taught me how to sew on a button, iron a shirt, and dust a banister. You let me put your donation envelope in the copper collection plate during Mass. You sang me German songs, found quarters behind my ears, and slapped your thigh at your own corny jokes. You gave me crisp two-dollar bills and a ballerina music box. We held hands when we went to Golden Gate Park, Fleishhacker Zoo, and Fisherman’s Wharf, my triple-time steps keeping up with your long stride. We took pictures with your Brownie; I have them still.

You ate bottles of aspirin and rolls of Tums. When I was sick, you rubbed Vicks on my chest, gave me two Aspergum, and stroked my forehead. Sitting on the edge of my bed, you had tears in your eyes as you remembered the only time your mother comforted you was when you were sick. You taught me how to sew on a button, iron a shirt, and dust a banister. You let me put your donation envelope in the copper collection plate during Mass. You sang me German songs, found quarters behind my ears, and slapped your thigh at your own corny jokes. You gave me crisp two-dollar bills and a ballerina music box. We held hands when we went to Golden Gate Park, Fleishhacker Zoo, and Fisherman’s Wharf, my triple-time steps keeping up with your long stride. We took pictures with your Brownie; I have them still.

You were tall and upright, with wire-rimmed glasses, blue eyes and gray hair, and smelled of Old Spice, Vitalis, and Listerine. You wore a suit and vest, a tie, and your felt hat with two small red and black feathers in its brim. Your starched white shirt hid muscles you built from working in construction and delivering ice. Offering your arm, you walked on the curbside and tipped your hat. Always the first to stand and the last to sit, you also held chairs, doors, and umbrellas. You had no sense of direction, none, and missed the same turn-off three times. You tried to fix the living room door when it was sticking at the bottom. You sanded it, sanded it again, and sanded it some more. Then you sawed it. When done, it was an inch and a half too short at the top. You re-hung it anyway, and were embarrassed every time anyone mentioned the gap. You cooked double-thick lamb chops, canned green peas, and new potatoes, and you loved fresh crab, asparagus, and French bread. You read Look, Reader’s Digest, and the The Saturday Evening Post. Blood made you faint. Alcohol made you sick. Arrogance made you mad. The Ten Commandments, good judgment, and common sense directed your life.

You ran a five-and-dime on Haight Street. After work we drove home along Stow Lake, counting the rabbits and squirrels. When I got my learner’s permit you let me drive, even though I scared you. When I was fifteen, you locked me out of the house while I was out with the neighborhood boys. When you told me to pack my bags, that I was going back to Carleen’s, I cried. You let me stay. I worked with you every summer from the time I was twelve until I got married. You taught me to make change, stock shelves, and take inventory; to sweep the floor, run the register, and watch for shoplifters. You taught me honesty and you taught me loyalty. You also taught me the cost of security: in twenty-five years of running a dime store, you never made more than $500 a month. You hated the Summer of Love, throwing buckets of cold mop water on the “goddam dirty hippies” when they slept against your shiny red-tiled storefront in the morning fog. You resented their freedom, sexuality and values, and detested their music, drugs, and panhandling. When the Haight—along with the world—changed, you closed the store.

On my wedding day you walked me down the aisle; you taught me to dance that day. You weren’t fond of my husband, but you loved our babies. You cradled, tickled, and kissed them. You fed Matt his first watermelon and Jon his first ice cream. We played cards and cribbage and you taught my sons to play too. They were easy to beat and fun to cheat and you laughed when they caught you.

At the movies during the nude scene (it wasn’t even a nude scene; she was standing at the second story window and slowly lifted her sweater off over her head while the cowboys watched from below), you were so startled you covered your eyes and threw your popcorn and Coke all over the people in the row behind us, your false teeth flipping out into your lap.

At your surprise seventy-fifth birthday party, you cried in the doorway of Sonoma’s Depot Hotel. For your twenty-fifth wedding anniversary you had your tiny 1852 gold piece made into a pendant for Marie. You asked me to give it to her, knowing you wouldn’t make it until then as cancer had spread to almost every part of your body. You could no longer walk, eat, or turn over by yourself. When the black-robed priest quietly appeared at your bedside to give you the last rites, you blurted, “Oh shit,” and ducked under the covers. Three days later, just before dawn, you took your last breath. They drove your body away in the back of an old brown station wagon. We got to say goodbye. You got to say you’re sorry. I got to say I love you.

I have your Kodak Brownie, pearl cufflinks, rosary beads, and your felt hat with the small red and black feathers. They all remind me of you, the best parts of you, and remind me of what I had.

I have your Kodak Brownie, pearl cufflinks, rosary beads, and your felt hat with the small red and black feathers. They all remind me of you, the best parts of you, and remind me of what I had.

Your daughter, Catherine (Clemens) Sevenau

Note: This was an exercise from a “three letter process.” Choosing someone with whom I had issues, I first wrote an anger letter, next a resentment letter (which was pretty much the same as the first), and then, when I’d exhausted my litany of complaint, a third that was just the facts, called a “what’s so” letter. This is my “what’s so” letter to my father.

June 9, 2016

Please Let Me Go

Writings~Rambles~Rhymes

- Catherine Sevenau's profile

- 6 followers