Catherine Sevenau's Blog: Writings~Rambles~Rhymes, page 63

August 26, 2015

Dad, God, and the Holy Ghost

1949: Sonora, California ~

Our parents never argued about how to raise their children. They argued about my mother’s smoking and drinking, and about her housekeeping, but not about the kids. She gave the older ones a swift kick or a snapping backhand when they didn’t move fast enough or do as they were told. When she was too lazy to get up, she’d warn, “You just wait ’til your father gets home!” She threatened to send the girls away to a convent, which hadn’t made one whit of difference in her attitude as a young girl.

To get Mom to calm down and have some peace and quiet for the night, Dad, slipping his brown leather belt from his pants, meted out an occasional token thrashing on Larry and Carleen’s bottoms, ignoring their seldom innocent protests with, “Even if you haven’t done anything wrong, this is for something you probably got away with or for something you’re planning to do.” Other than that, our father was a soft-spoken man of few words.

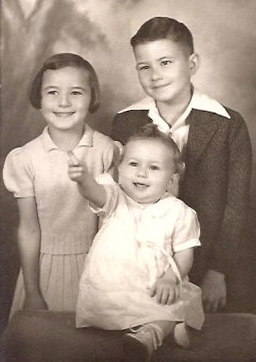

Larry, Carleen, Betty, Claudia

As the kids got older, Dad got smarter. Whenever anything went wrong, he’d line up the kids by age, and get out his small black leather bound Bible. Starting with Larry, he’d have them raise their left hands, place their right on the good book, and make them swear to God that they would tell the truth.

“Did you steal the change from cookie jar?” Dad queried them, one at a time.

“No,” was the stock answer down the row.

“Do you know who did?” The questioning started again at the head of the line.

Claudia

Larry was seldom guilty. Carleen and Betty could lie through their teeth to Dad, God, and the Holy Ghost; it didn’t bother them a bit. Claudia lived in perpetual puzzlement that her dark-haired sisters could lie, and not live in the same fear of God she did. Petrified, she believed God and Dad were the same: big, powerful, and all knowing. She never committed any wrongdoing, but more often than not, she knew who did, and Dad knew she’d tell. Carleen was typically the culprit. Betty usually got blamed. Poor Claudia lived in a hell of her own making. First of all, she didn’t want to be singled out or noticed. Second, she didn’t want anyone to think badly of her so she did her best to be good; and third, her siblings constantly retaliated against her for being a little tattletale and goody-two-shoes. Her skinny right arm often hung sore and useless, black and blue from being punched. They didn’t understand their golden-haired sister had no choice. She was answering to a higher power.

August 20, 2015

Sign of the Cross

1952: Chico, California ~

For thirty-seven years my grandmother, Nellie Chatfield, attended daily mass at St. John the Baptist Catholic Church in Chico. Even if she took seven years off for vacations, illness, or emergencies, that would still leave thirty years, which amounts to 360 months, or 1,140 some weeks, or 10,950 days. That’s a lot of time for her to sustain and strengthen her moral superiority.

If it is a habit of the righteous to believe one’s soul may be saved by going to church, if attendance on Sundays could make one virtuous, and if attendance on holy days could ensure one’s true holiness, then my grandmother reasoned that going every day would certainly earn her a seat at the right hand of God… the best seat in the house from which to dispense virtuous judgment.

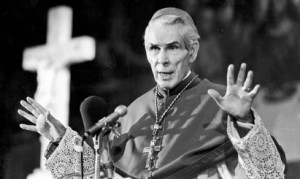

In her final years, Grandma Nellie had a television set, and she never missed Bishop Sheen’s Holy Hour. Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, a writer, preacher, and teacher, was an evangelist of the airwaves. Every Sunday at 6:00 p.m. she watched his holy hour from her slide rocker. The show was not an hour of devotion, but rather of redemption, and with it he brought vast numbers of converts to the Catholic Church. He wrote, “Every human being at his birth has everything to learn. His mind is a kind of blank slate on which truths can be written. How much he will learn will depend on two things: how clean he keeps his slate and the wisdom of the teachers who write on it.” Grandma Nellie, who perceived herself as appointed warden and keeper of morals, thought he said it was her job to keep her eye on everyone else’s slate. With her rosary twisted, she was here to judge the world, not save it.

In her final years, Grandma Nellie had a television set, and she never missed Bishop Sheen’s Holy Hour. Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, a writer, preacher, and teacher, was an evangelist of the airwaves. Every Sunday at 6:00 p.m. she watched his holy hour from her slide rocker. The show was not an hour of devotion, but rather of redemption, and with it he brought vast numbers of converts to the Catholic Church. He wrote, “Every human being at his birth has everything to learn. His mind is a kind of blank slate on which truths can be written. How much he will learn will depend on two things: how clean he keeps his slate and the wisdom of the teachers who write on it.” Grandma Nellie, who perceived herself as appointed warden and keeper of morals, thought he said it was her job to keep her eye on everyone else’s slate. With her rosary twisted, she was here to judge the world, not save it.

Nellie’s other Sunday ritual was tuning into the Ed Sullivan Show, a mix of vaudeville, comedy, and music. She adored his show, except when the Rockettes came on; she thought them scandalous, horrified by their skimpy skirts and bare legs kicked over their heads. She insisted they were sinful. Making the sign of the cross, she also insisted the small black and white television not be turned off so she could watch, leaning forward in her rocker, cleaning the dust specks from her wire-rimmed glasses.

Nellie’s other Sunday ritual was tuning into the Ed Sullivan Show, a mix of vaudeville, comedy, and music. She adored his show, except when the Rockettes came on; she thought them scandalous, horrified by their skimpy skirts and bare legs kicked over their heads. She insisted they were sinful. Making the sign of the cross, she also insisted the small black and white television not be turned off so she could watch, leaning forward in her rocker, cleaning the dust specks from her wire-rimmed glasses.

August 13, 2015

Dharma

“We’ve been brought here for a very short time, against our will, and we don’t know why.” I love that line.

What is the point of our birth and life and death? Why are we here? What is our true purpose? These thoughts keep some of us up at night; others have never examined the questions. Some think life is meaningless, that it has no purpose, that it is simply a terrible misunderstanding. Others make it mean whatever they want it to mean.

I don’t believe any of us are here on a whim; I think each of us has a purpose—even if only to serve as a warning for the rest of us. But for whatever reason we’re in this body on this planet at this time, we all have gifts to give, we all make a difference, and we want to matter.

Suppose that we are here to discover our true selves, and to serve others through our unique, creative expressions. I’ve been fortunate to have talented teachers in my life, mentors who lived according to their true callings, knew their purposes, their reasons for being. Two are paramount, and both have died. In May of 2001, Michael Naumer, a man whose life’s work was about consciousness and transformation, moved on. Dying of lung cancer, in debilitating pain, and knowing he had little time left, he chose to end his life with a pistol. My dance and writing teacher, Stephanie Moore, died from uterine cancer. She went out in January at the tail end of the wild storms that hit Northern California in late 2005 and early 2006. Stephanie was also not one to go gently into the night.

Birthing Ancestors Mandala

artist: Tony Scheving, a fellow student of Michael Naumer

Both Michael and Stephanie understood their dharma, their true purposes and unique vocations in life. They held their teaching—be it dance, writing, or consciousness—as their responsibility and duty to others, and it’s also what they lived for. Not everyone could hear what they had to say, or were interested, but many hung on for the ride, and it was wild. They taught us to create and live up to our standards, not theirs, and to see the world with wider eyes. They brought out the best in many of us, turned us into dancers who felt our own rhythms, writers who found our own voices, and questioners who found our own answers. Rattling our cages, they shook loose our cobwebs. They were committed, passionate, on fire, and gave generously of themselves. Death ended their lives, but not our relationship. I forever nod to them for rocking my boat.

Stephanie Moore

1951 – 2006

I met Stephanie when I was thirty-nine; over the next five years, she taught me to dance—which was no small feat for someone with two left ones. I’d left my body as a child as there where times when it was dangerous to inhabit it. I think because of that I’d no sense of space or direction and was constantly tripping, bouncing off doorframes, or knocking things over—a thin, wan, train wreck covered in tattered Band-Aids. Dancing moved me back into my interior. I grin when referred to as elegant; if they only knew. I’ve been twirling and two-stepping for twenty-eight years now, and I bless Stephanie whenever the sound of a waltz drifts my way. My friend changed her direction in life from accomplished dance instructor to gifted writing teacher. At the age of fifty-four, I picked up a pen; she read my poem “Queen Bee” and from that, I found myself for the next few years in her Monday night writing class. That was the genesis of my family memoir.

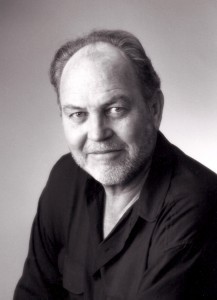

Michael Naumer

1942 – 2001

I met Michael when I was forty-six. In 1995 I took his and wife Christina’s three-day course, the Mind of Love, and continued with the graduate work as it morphed into Beyond the Game. Michael also gave me the opportunity to assist him in the weekend workshops for the last two and a half years they were offered. All in all, I took that course twelve times, along with five continuous years of Tuesday night graduate classes. I’ve done so much transformational work you’d think I’d be enlightened. That would be no, but at least I’m no longer asleep. Michael’s work influenced my thinking, writing, and way of being. I began to understand that things were happening for me, not to me. I developed the ability to turn my index finger around, without breaking it, to see my part. I learned that the mind is a dangerous neighborhood, and not to go in there alone.

These two will always be a part of my daily dance. I still hear Stephanie’s coaching: “that was perfect; just one thing” and Michael’s echo at the end of many a point, “and then some.”

So why am I here? Looking for my life’s purpose was like a fish looking for water: though it was all around me it took me a bit to see it. When I examined my commitments, where I direct my energy, where I lose track of time amidst my total absorption, my unique gifts became apparent: I’m a connector, here to keep “family” together: historically, biographically, and personally. I’m here to be a storyteller, to make people think and to make them laugh. I’m here to teach: I know a lot about some things and a little about others. These engagements, individually and in concert, dance inside my heart.

I didn’t choose the ways in which I’ve spent my life, rather, they subtly chose me; I get this magnetic pull inside me where wild horses couldn’t stop me. I didn’t plan on starting a carrot juice company, any more than I planned on owning a real estate business. Nor did I plan on getting married and being a mother, a business woman, a seeker, a dancer, or a writer. Life happens: my childhood, genetics, and karma have played a part, as have the choices I’ve made. I listen to that pull in my gut, even when it makes no sense. I pay attention to the clues that come my way, and connect the dots. I notice when synchronicity appears. Curiosity, excitement, and trust propel me on the path of creating and doing what I love. It’s endless and ever changing. I don’t worry when I’ll get there (as there is no there) so I follow my heart and continue on that winding path, wherever it may lead. It also matters not that I have no sense of direction; I always end up where I need to be, even if I’m not happy with where I am.

There was a time when I struggled, when I had no idea what I was supposed to be doing to make a difference. In my angst, a wise friend and teacher gently put his hand on my shoulder and said, “You don’t have to do anything, you just be you.” Seems easy enough, to show up and simply be me, except for those times when I wear my halo a little too tight or am annoyingly bossy; then I get to be the warning for others. Oh well. Sometimes you get to be the windshield, sometimes you get to be the bug.

Mandala of Creation; artist: Michael Naumer

August 9, 2015

Bloodlines (original version)

This tale is a history, a fable, a prayer;

of those gone before me, now gathered with care.

Can’t start in the middle—too confusing, not clear,

can’t start at the end—will be over I fear.

So I’ll start from the first as far back as I can

and nudge you along ’til you’ve met the whole clan.

When you are finished you’ll know who we are,

how we all got here, how we came from afar.

They came as stonemasons, shoemakers, and deacons,

joining the New World as seekers and beacons.

Peter left Consdorf and sailed ’cross the sea,

laid roots in Mazeppa, my father’s fine tree.

George hailed from Sussex to start a new life

and settled in Guilford with children and wife.

These pioneer woodsmen were ranchers and farmers,

God-fearing Christians, heathens, and charmers.

Conducting the railways or working the land,

some branded cattle, a few dealt a hand.

They were shopkeepers, landowners, soldiers, and teachers,

they were butchers and icemen, a few wannabe preachers.

They were writers and singers, a political few,

they were German and English, a Frenchwoman too.

Generations before them, their stories are gone,

’til they sailed on the Phoenix, Diligent, and St. John.

Lucky for you, not on each I’ll shed light

for if I dared try we’d be here all night.

I’ve heard which ones fiddled, who sang, and who danced;

I’ve no doubt they worked hard, wonder if they romanced.

I’m told of my grandfathers’ heartache and strife,

know where they built, what they did with their life.

I know what they died of: bad kidneys and rage,

some from weak hearts, some of old age.

Some died from smoking, from whiskey, from sin,

from choler, from cancer—or did themselves in.

I sense all their voices; they touch me in dreams,

I glimpse at their lives to unearth what it means.

Herein are their legends, their letters and lore,

some clippings and pictures that show what they wore.

Regarding the women so little was written,

so little recorded ’bout how they were smitten.

I know what they cooked and what they were taught;

know many were Catholic—which tells me a lot.

They were strong and defiant, ruled by what’s right;

married men that some left but made do with their plight.

These mothers of mothers, and mothers of mine,

are grown from seed you don’t often find.

I can guess at their dreams, their motives, their fears,

by knowing what mine are—my shadows and tears.

I presume who they were by looking at me,

our blossoms and thorns twine in the same tree.

I’ll write of the kin my brother explored,

searching volumes of records—a task I deplored.

Names, facts and figures, they interest me not,

it’s the echoes of tales where I am most caught:

the Hoys sued each other, Grandpa gambled the ranch,

and drowned all his sorrows—a curse through that branch.

Emily hid her first marriage, bandits shot Val and ran,

Nella Mae had four children by not the same man.

Clans traveled in numbers through region and state,

settled Montana, Colorado, California of late.

It was here in the thirties my parents did meet,

then married, had children with ten little feet.

I am the youngest, this teller of tales,

unearthing my family, removing our veils.

I’m related to Clemens, the kin of my dad

(who married a Chatfield—a girl some thought bad).

I’ve written of both, their histories, their lives,

of Mom’s other husband and Daddy’s three wives.

I wrote of my brother, my sisters and me,

recording our versions, our own memories.

But futures are clouded by sins of the past

with history rewritten by those who come last.

So pull up a chair and sit by my side,

come wander with me through this family’s ride.

We’re scattered and distant—all over the place

though still all related by marriage, or grace.

Through bloodlines or love, through bad luck or tether,

Doesn’t matter one whit what binds us together.

Those gone before are a part of us still,

a dram of our blood, a slice of our will.

They watch over us with wonder and trust

and guide us from birth ’til we, too, turn to dust.

I know they’ll excuse me—my gaffes and asides,

it’s those who are living that might have my hide.

Some snort, some are angry, some threaten, some rear;

some nights I don’t sleep from the scorn that I fear.

But it’s none of my business what they think of me—

I wrote what I deemed ‘bout my family tree.

Catherine Frances (Clemens) Sevenau

original version, 2005

Clemens photos

Chatfield pictures

Bloodlines

This tale is a history, a fable, a prayer;

of those gone before me, now gathered with care.

Can’t start in the middle—too confusing, not clear,

can’t start at the end—will be over I fear.

So I’ll start from the first as far back as I can

and nudge you along ’til you’ve met the whole clan.

When you are finished you’ll know who we are,

how we all got here, how we came from afar.

They came as stonemasons, shoemakers, and deacons,

joining the New World as seekers and beacons.

Peter left Consdorf and sailed ’cross the sea,

laid roots in Mazeppa, my father’s fine tree.

George hailed from Sussex to start a new life

and settled in Guilford with children and wife.

These pioneer woodsmen were ranchers and farmers,

God-fearing Christians, heathens, and charmers.

Conducting the railways or working the land,

some branded cattle, a few dealt a hand.

They were shopkeepers, landowners, soldiers, and teachers,

they were butchers and icemen, a few wannabe preachers.

They were writers and singers, a political few,

they were German and English, a Frenchwoman too.

Generations before them, their stories are gone,

’til they sailed on the Phoenix, Diligent, and St. John.

Lucky for you, not on each I’ll shed light

for if I dared try we’d be here all night.

I’ve heard which ones fiddled, who sang, and who danced;

I’ve no doubt they worked hard, wonder if they romanced.

I’m told of my grandfathers’ heartache and strife,

know where they built, what they did with their life.

I know what they died of: bad kidneys and rage,

some from weak hearts, some of old age.

Some died from smoking, from whiskey, from sin,

from choler, from cancer—or did themselves in.

I sense all their voices; they touch me in dreams,

I glimpse at their lives to unearth what it means.

Herein are their legends, their letters and lore,

some clippings and pictures that show what they wore.

Regarding the women so little was written,

so little recorded ’bout how they were smitten.

I know what they cooked and what they were taught;

know many were Catholic—which tells me a lot.

They were strong and defiant, ruled by what’s right;

married men that some left but made do with their plight.

These mothers of mothers, and mothers of mine,

are grown from seed you don’t often find.

I can guess at their dreams, their motives, their fears,

by knowing what mine are—my shadows and tears.

I presume who they were by looking at me,

our blossoms and thorns twine in the same tree.

I’ll write of the kin my brother explored,

searching volumes of records—a task I deplored.

Names, facts and figures, they interest me not,

it’s the echoes of tales where I am most caught:

the Hoys sued each other, Grandpa gambled the ranch,

and drowned all his sorrows—a curse through that branch.

Emily hid her first marriage, bandits shot Val and ran,

Nella Mae had four children by not the same man.

Clans traveled in numbers through region and state,

settled Montana, Colorado, California of late.

It was here in the thirties my parents did meet,

then married, had children with ten little feet.

I am the youngest, this teller of tales,

unearthing my family, removing our veils.

I’m related to Clemens, the kin of my dad

(who married a Chatfield—a girl some thought bad).

I’ve written of both, their histories, their lives,

of Mom’s other husband and Daddy’s three wives.

I wrote of my brother, my sisters and me,

recording our versions, our own memories.

But futures are clouded by sins of the past

with history rewritten by those who come last.

So pull up a chair and sit by my side,

come wander with me through this family’s ride.

We’re scattered and distant—all over the place

though still all related by marriage, or grace.

Through bloodlines or love, through bad luck or tether,

Doesn’t matter one whit what binds us together.

Those gone before are a part of us still,

a dram of our blood, a slice of our will.

They watch over us with wonder and trust

and guide us from birth ’til we, too, turn to dust.

I know they’ll excuse me—my gaffes and asides,

it’s those who are living that might have my hide.

Some snort, some are angry, some threaten, some rear;

some nights I don’t sleep from the scorn that I fear.

But it’s none of my business what they think of me—

I wrote what I deemed ‘bout my family tree.

Catherine Frances (Clemens) Sevenau

original version, 2005

Clemens photos

Chatfield pictures

July 30, 2015

Dick and Jane

Audio: click arrow to play

http://sevenau.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/12-Dick-and-Jane-•-1956-San-Jose.mp3

Dick and Jane • 1955, San Jose, California

Jefferson Elementary was like all grammar schools: the classrooms arranged with five rows of seven metal wood-topped desks; the playground as barren and flat as a prison yard; the morning and midday recesses echoing the cacophony of unruly children.

I remember a lot about second grade: the finger-paints, watercolors, and pull-down maps, the damp winter cloakroom piled with dripping raincoats and soggy boots, the screech of chalk, ticking clock, and the whirl of the sharpener spewing pencil dust on the wall by Miss Harrison’s desk. I can still smell the white paste and buff paper with wood chinks and blue lines. I even recall the taste: the flaky crumbs and gummy texture of graham crackers washed down with a half pint container of milk, and the taste of chewed Ticonderoga pencils.

I remember Dick and Jane.

“See Jane run. Run Jane, run.”

I knew exactly how Jane felt. I wanted to run too.

We had monthly fire drills, holding hands two-by-two, boys in one line, girls in the other, marching away from the low, one-story building built like a bunker. During air-raid practices we crouched like rolled up pill-bugs under our desks, our arms protecting our heads. But there was never a nuclear attack, and even if there was, it was unlikely that an inch-thick desktop was going to protect me. Oh please… I had enough real dangers in my life to fret about.

There were things I liked about second grade, and things I didn’t. I didn’t like sitting smack dab in the center of the middle row of desks. Praying no one would notice me, I kept my eyes lowered, fingering the skate key I wore around my neck like a rosary, aching to suck my fingers. Terrified of being caught and called a baby, I chewed my nails or orange pencils instead.

There were things I liked about second grade, and things I didn’t. I didn’t like sitting smack dab in the center of the middle row of desks. Praying no one would notice me, I kept my eyes lowered, fingering the skate key I wore around my neck like a rosary, aching to suck my fingers. Terrified of being caught and called a baby, I chewed my nails or orange pencils instead.

I didn’t like the playground. The swings and merry-go-round made me queasy and the jungle gym and high bar scared me to death. The teeter-totter was dangerous, especially when the fat, redheaded kid with glasses thought it a riot to roll off sideways when he was at the bottom and I was at the top.

I liked reading stories and practicing letters, and staying inside when it rained. I liked drawing and the feel of smooth paper and the smell of waxy crayons. I always drew the same house: it had a peaked roof, a green door, one window, a big tree to the left, a lemon yellow sun shining in the upper right, and a row of red tulips in front.

What I liked the most was lunch. Eating my peanut butter and jelly sandwich, my three Oreo cookies, and a small red box of Sunmaid raisins, I balanced myself on the cement curb at the far corner of the playground. Hunching my shoulders and raking my heels back and forth, making small hollows in the bald hardpack, I sat by myself and watched the other girls play four-square and hopscotch. Some days, Kendra, whose parents were deaf mutes, sat with me. I fed my crusts to the blackbirds and gave Kendra my raisins; they made my cavities hurt.

Kendra taught me to sign. One day, from her blouse pocket, she presented me with a small folded card that showed me how to hold my hands for each letter so I could practice on my own. I thought maybe I could teach Mom, maybe break the silence another way. But my mother wasn’t interested; the only voices heard in our house were the ones in her head.

July 23, 2015

Where Babies Come From

Watsonville, California: 1939

Our house was right on her way home from grammar school and Marceline (Uncle George and Aunt Verda’s daughter) loved to stop off and visit mom. Marceline held her Aunt Babe in high esteem, elevating her to a kindred spirit and favorite aunt. She thought our mother a much better mother than hers: Mom wasn’t as proper and strict as Verda, didn’t fuss about what the house looked like, didn’t care if her kids ran wild, didn’t give a whit about going to mass. She also talked to her niece about anything that she wanted to talk about.

Day family: George Jr, Jimmy, Aunt Verda, Marceline, Uncle George in Watsonville, circa 1939

Eleven-year-old Marceline was there so often she seemed to be part of the furniture. One warm afternoon she quickly tripped up the porch stairs just as Aunt Babe woke up from her daily nap on the living room sofa. Babe hadn’t been feeling well, and when Marceline asked why, she confided to her young niece that she would have a third child soon.

Marceline was crazy about babies, and wanted her parents to have another one, too. She loved taking care of my sister Carleen (Marceline was six years older) and wanted more than anything to have a little sister of her own. It had been on her wish list forever. She’d asked her parents, but they’d emphatically said no, they couldn’t. Left to her own devices, and thinking hard, she worried that perhaps they didn’t know how (disregarding the glaring fact that she already had two older half-brothers and one younger brother, not to mention herself).

Marceline had all kinds of questions for her Aunt Babe: “How did you get Larry and Carleen? Where do babies come from? How long does it take to make one?”

So my mother—being Mother—took a drag off her cigarette and told her.

At dinner that night, Marceline, beside herself with excitement and thinking they could use this information, explained the process pretty well to her parents. George exploded, his fist slamming the table. “Cheesus.H.Christ! Goddamnsonuvabitch! Jesuschristalmighty! Who in the goddamsonuvabitchinhell told you WHERE BABIES COME FROM?”

“Aunt Babe,” supplied Marceline helpfully.

George glared at Verda, “Your goddam sister …” In high dudgeon, he grabbed Marceline and Verda by their arms and marched over to our house, bounded up the porch, pounded on the screened door, stormed in, and bawled his sister-in-law out royally for taking it upon herself to inform their daughter of life’s private details.

Jabbing his finger with fury towards Babe, he ranted, “You had no goddam business talking to Marceline about this, especially at her age! That’s our job, goddammit! What in the hell were you thinking, and why for chrissakes do you think you had the right to do such a goddamn foolish thing?”

The women in my family don’t mince words, which is unfortunate as it would make them so much easier to eat later. Babe simply looked at him, shrugged, and said, “Well, she asked me.”

Carleen, Larry, Betty (seated), Watsonville 1940

That December, my sister Elizabeth Ann “Betty” Clemens, the third child in our family, was born—and perhaps as a result of Marceline’s coaching, her own much-wanted sister Judi was born almost exactly a year later.

July 16, 2015

Dead People, Sparkle Fairies, and Hitler

“Oma, there’s dead people under those stones, you know.”

I glance over my shoulder to see what Satchel is talking about. My four-year-old grandson is commenting from his car seat about the small cemetery to our left on East Napa.

“I know Satchel, that’s where they put our bodies when we die.”

“I know Satchel, that’s where they put our bodies when we die.”

“What do they do with the heads?” he asks.

“Well, when we die we don’t need our bodies any more,” elaborating with a spiritual conversation about bodies and souls and death.

When I finish, he says, “Yeah, but what do they do with the heads?”

As I attempt to expound further, he interrupts and announces, “Oma! The car is filled with sparkle fairies!”

I’m wearing a Brazilian rhinestone bracelet my sister Liz gave me, and the sun is bouncing off the facets, casting the car’s interior with hundreds of tiny brilliant refractions.

He asks in wonder, “Can you see them?”

“I can, Satchel, that I can.”

Then he tilts his head forward and says, “Oma, can you see the Apple Fairy on the top of my head?”

I peer in the rearview mirror, slip into his world of magic, and tell him, “Of course. How long has she been there?”

“About a week!”

“A week! That’s amazing. You are certainly a lucky boy, Satchel.”

Days later, when I was telling my friend Elaina the cemetery story, I hadn’t understood his question until she laughed and said, “Well, you told him what they did with the bodies. He wanted to know what they did with the heads.”

I haven’t gotten back to him on that one.

*****

My son Matt took Satchel to Mountain Cemetery on Memorial Day to honor Satchel’s deceased great-grandfather Calvin Frost, and dropped him off afterwards to spend the day with me.

In great excitement Satchel bursts through the front door. “Oma! Oma! Did you know that Grandpa Cal fought in the war and won all the battles and at the end of the war he killed Hitler?”

“Do tell. I think you got most of the story right.”

“What?” he asks, stopping short.

“Well, Grandpa Cal did fight in the war, and he may have won all the battles, but at the end of the war he didn’t kill Hitler.”

“Who did?”

“Hitler was the leader of Germany and a very bad man. When the Allied Forces invaded his country, he knew he’d lost the war and would be taken prisoner, so he killed himself.”

“Oh.” He lets this sink in, then asks, “Do you have any pictures of Hitler?”

“Not hanging on my walls, but I suppose we could find what he looks like on the computer.”

After some time on the Internet, he’s satisfied and says, “Oma, you were right. Hitler was a very bad man.” He thinks a bit, then says, “Do we have any bad men in the family?”

“No, but we have someone in the family who was killed by a bad man.”

“Who!”

“Harry Tracy was a very bad man in the wild west, and he shot Valentine Hoy, my great-grandmother’s brother.”

“Do you have any pictures of him?”

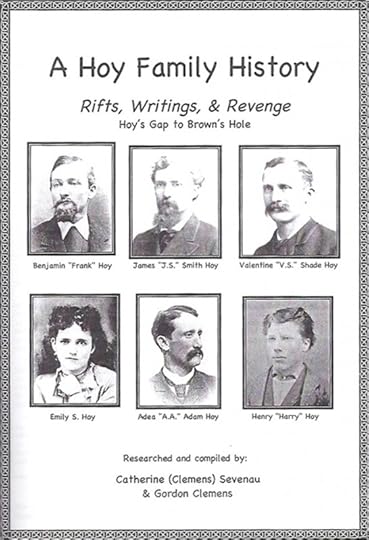

“Well, as a matter of fact, I do.” I pull out my book of Hoy history and show Satchel the pictures of Harry and Valentine.

“Well, as a matter of fact, I do.” I pull out my book of Hoy history and show Satchel the pictures of Harry and Valentine.

He asks, leafing through it, “Oma, what is this?”

“It’s a book Uncle Gordon and I put together about our family history. This one is on my mother’s side of the family, and it’s about her, and her parents, and their parents, and all of their families on our Hoy side, from the time they left Germany to come to this country.”

“Is my mom’s family in here?”

“No,” I say, “it’s your dad’s side of the family.”

He turns the pages, interested in everything.

“Would you like a copy of it when you grow up?” I ask him.

“I would,” he says, oh so very earnestly.

“I knew I liked you,” and kiss the top of his head.

The next day I get a call from his father. “Is there any particular reason you’re having a conversation with my son about Hitler?”

To that I respond, “Hey, you’re the one that opened it up. I didn’t bring him to the cemetery, you did. I was simply answering his questions.”

*****

As I’m getting lunch together, Satchel is on my kitchen floor with both legs encircling my ankle, his arms around my calf. When I try to walk away, he hangs on, hoping for a ride. I’m wearing black cowboy boots.

I lose my balance and bark, “Watch out! If I come down on you with my heel, you won’t be having any children.”

“What do you mean I won’t be having any children?”

“If I crush your cojones, you won’t be able to have kids.”

“What do you mean, I won’t be able to have kids?”

Ohmygod. I’ve had the death conversation. I’ve had the Hitler conversation. And now I’m heading into the sex conversation with a four-year-old?

I stutter and stammer. “It’s just, well, it’s just, it’s just, it’s just a…,” grasping for words.

He saves me: “Oh, you mean, it’s just a saying?”

“Exactly, it’s just a saying.” I exhale with relief. It’s not like I’ve already been in enough trouble this month answering this kid’s questions.

July 11, 2015

Meltdown

Satchel, Easter 2006

My grandson is three, and this is the second time I have him for an extended period at night. Brooke and Matt are in San Francisco, returning around 11:00.

We spend the afternoon and evening at my house doing all the things we love to do together: cooking, eating, and reading the books I read to his father and Uncle Jon when they were his age. I taught Satchel to make scrambled eggs, which is now his specialty.

Getting him into his dragon pajamas, I tell Satchel it’s time to go home. “NOOOO! I want to stay here!”

“C’mon. I’m supposed to have you home and in bed in an hour.” He throws himself on the floor, kicking and screaming, apparently possessed. I’m taken by surprise as he’s such an even-keeled little guy. I scoop him up and head downstairs. Turned into a writhing demon and trying to escape from my arms, he nearly throws us both down the staircase.

When we get to the bottom he hurls himself to the floor, completely out of control.

“Satchel, get up and stop it.”

His screaming escalates. I give fair warning. “If you don’t stop, I’m going to smack your bottom.” What I really wanted to do was take a fire hose and blast him, but I didn’t have one handy.

“Okay, I warned you.” I lift him up by his skinny little arm and give him a swat on the butt. He’s so shocked, he stops. Then, he proceeds into a meltdown of uncontrollable tears, sobbing and shaking, beyond the point of being able to get ahold of himself.

After some minutes of this, I bargain with him: “Look, if I take you to Busha’s (his other grandmother) will you quit crying?” He nods between sobs. Of course I don’t have her number and only vaguely know where she lives. He assures me he can find her house. We circle her neighborhood three times while he hiccoughs through sobs in the back seat.

He poses, “Mmmm. Turn here.” Then, “Mmm, turn here.” He has no idea how to get there either. I realize this when he wants me to cross the highway to Boyes Boulevard. Why am I trusting the directions of a three-year-old? As I drive past my friend Rhonda’s house, I think, maybe a third person can snap him out of this. She’s home.

Satchel and Oma, Sept 2006

We pick figs and pears and slice them up on her back porch. Then she brings out a box of magic toys and Satchel and I put on matching red noses. She takes our picture, noting we look quite a lot alike. Satch has calmed down, though still not himself.

It is well past sunset by the time I deliver him to his house, but as I try to put him to bed, the tears and wracking sobs return. For the next hour and a half I sit on the front porch steps in the dark, rocking him back and forth, his sobs continuing through his drift toward sleep.

When Matt and Brooke come home, I tell them how the evening went.

Matt calls the next day, not happy with me. “We don’t spank him you know.”

“I’ve noticed.”

“Did you spank us when we were kids?”

“Apparently not enough,” I respond.

“You did too, you spanked us with the wooden spoon!”

“I did not, I chased you with the wooden spoon—but you both were too fast. I did not spank you, and Aunt Liz was the first one to spank Jon, an event he’s still not recovered from. I did wale on him a couple of times after that, however.”

“Look Matt, I want to honor how you raise your child. But I’m telling you, he ever pulls that with me again, you’re coming to get him, I don’t care where you are. And by the by, just what do you suggest I should have done?”

“Well, we put him in his bedroom and hold the door knob so he can’t get out.”

“Yeah right, that would be unsafe to do in any room in my house, and would go over real big at my office.”

I didn’t see Satchel for a couple of weeks. Supposedly he was still mad at me, but I’m pretty sure kids don’t hang onto things that long. The small kids, anyway. Two weeks later we’re at the park and I’m pushing him in the swing.

He asks tentatively, “Oma, can we go to your house?”

“Forget it. Last time we were at my house you got upset and I got in trouble. We’re staying right here on neutral ground.”

Looking up with the same brown eyes his father had when he was little, my grandson says in a quiet voice, “Then maybe can we go next week?”

“We can go next week—on one condition. When I ask you to do something, you don’t throw a hissy fit when you don’t get your way. Deal?”

“Deal!” he promises.

Postscript, five years later:

“Oma, I remember when you spanked me.”

“Good, and as far as I can tell it worked out great.”

“It hurt you know.”

“Oh for godsakes, you had on diapers and it was one well-placed swat. And it wasn’t like I was punishing you, I was trying to snap you out of a meltdown. The only thing I hurt was your feelings, and I think you’ve recovered by now.”

Satchel, 4th grade

Postscript, six years later: Satchel now has a four-year-old sister.

Marching irately through my front door he says, “Oma, you’ve got to do something about Temple. She gets away with everything; she hits me, she’s completely out of control, and all they do is give her time-outs and she doesn’t even care.”

“Why me?”

“Because you’re the only one in the family who can do anything about her!”

Temple, nearly five

“So what do you have in mind?” I ask, knowing exactly where this is heading.

“Well, could you spank her?”

“Oh sure. I smacked your bottom once and your parents didn’t talk to me for a month. I’m not laying a hand on that child. Sorry, you’re on your own on this one, Cupcake.”

June 26, 2015

A Higher Possibility

Consciousness is that which recognizes itself.

Everything changes. Everything happens in cycles. Everything contributes.

Everything contains within itself the seed of its apparent opposite.

Everything is important—and nothing is significant.

There are no accidents.

Things are not happening to me—they are happening for me.

Do I want to be right—or do I want to be effective?

Am I available for what I say I want?

What is my part?

Expand to include and have it contribute.

There is no meaning in reality. Truth does not mean anything—it is just what’s so.

No good deed goes unpunished.

The mind is a dangerous neighborhood; don’t go in there alone.

Our baggage is the material we need to transform. We need our stuff—we just want to become objective about it so we can deal with it.

If you are going to be there, be there. If not, go someplace else.

Whatever you hold as “this shouldn’t be,” you energize its continued existence.

What you can’t choose you have to hold as burden.

Where you are the most wounded, you are the most accomplished.

Where you stumble is your gold.

When you get your limits you get your maturity.

When you diminish another person you lose their ability to contribute to you.

As long as you have to live inside the tribe, you cannot be a leader.

As consciousness rises, significance drops away.

The universe is not oppositional—only our minds are.

It is all, all working.

It is better to ride the horse in the direction it is going.

It is not about me. It may have something to do with me, but it is not about me—or my value. Nor is it about you—or your value.

Do not assign emotional responsibility to another. They don’t cause it—they only occasion it.

Gathering evidence: the way in which we organize our resistance.

Get the debt out of relationship.

Relationship will not fill my gap (the solution becomes the problem).

There is a difference between taking a stand and being a stand.

Position creates opposition. When I take a position, I have to defend it.

Context determines content.

Attachment produces dependence, dependence produces complaint. You can’t get to satisfaction from complaint.

Complaint is an abdication of responsibility.

Expectation shuts it down.

Love is the recognition of the equal in the other.

People are miraculous surprises.

Sometimes you eat the bear—and sometimes the bear eats you.

— quotes from Beyond the Game, by Michael Naumer

Michael Naumer

1942 – 2001

Michael Naumer started his work with his wife Christina in their course, The Mind of Love, which later morphed into Beyond the Game. Incorporating concepts from Gurdjieff, Oscar Ichazo, and Werner Erhard, they created a transformational body of work where the objective was one of self-recognition. The main course, along with the graduate work, delved into the above principles, and then some—the teachings about choice, reality, logic, and transformation. The purpose of the course was self-recognition, where Michael deemed, “the purpose of relationship was not to make oneself happy, but was a useful vehicle for seeing oneself. ” Beyond the Game was a higher game: chess, not checkers. It was a game not to be missed.

Writings~Rambles~Rhymes

- Catherine Sevenau's profile

- 6 followers